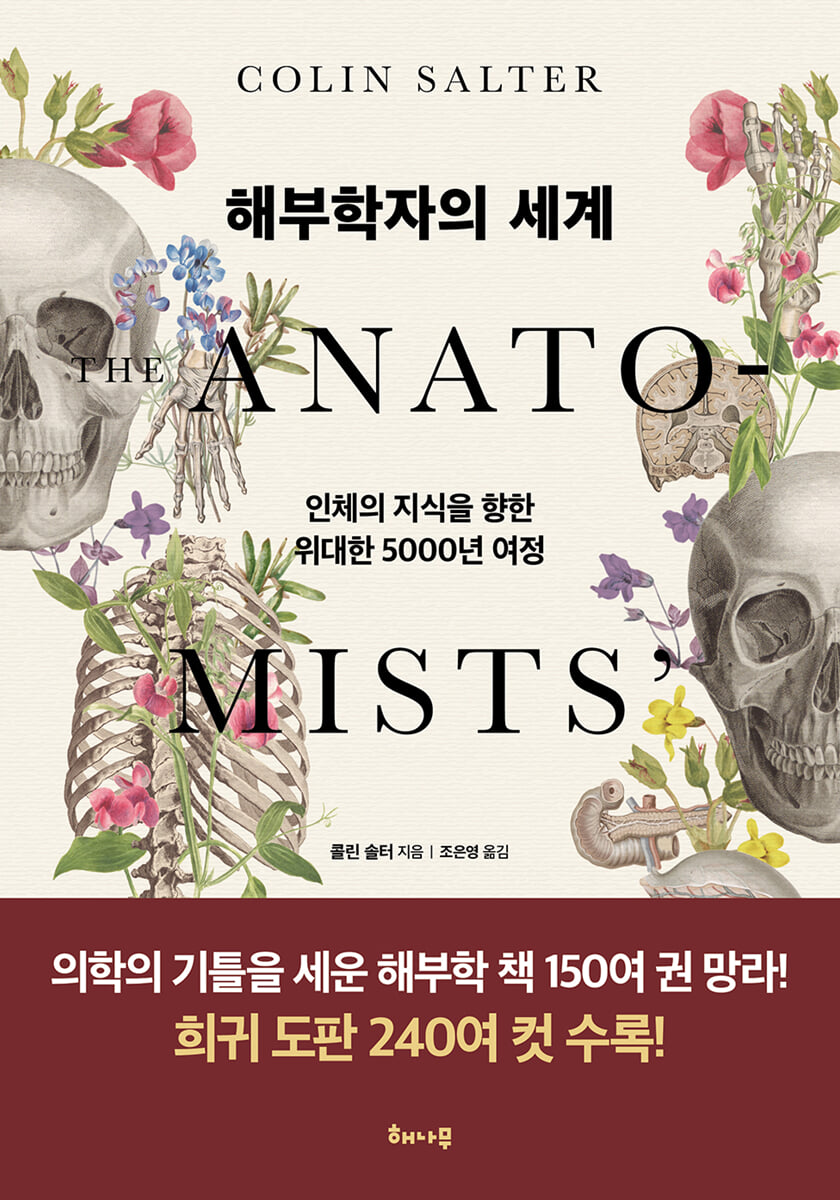

The World of Anatomists

|

Description

Book Introduction

How were the internal workings of our bodies discovered? How were the names of each organ given? From ancient Egypt to the Renaissance, modern times, and the 21st century, the books that have filled anatomists' libraries for approximately 5,000 years contain a history of understanding the human body, artistic techniques, and social change.

"The Anatomist's World" unravels the vast narrative of over 150 historically significant anatomy books published in Europe, the Middle East, China, and Japan.

This treasure-trove of stories unfolds, including the transition of anatomy from philosophy to empirical science, challenges to authority and new discoveries, the establishment of dissection theaters, the problem of grave robbers and the enactment of laws related to dissection, the development of artistic and graphic anatomical drawings and printing, and controversies over plagiarism.

Immerse yourself in the world of anatomists with these incredibly detailed, vivid, and beautiful anatomical illustrations.

"The Anatomist's World" unravels the vast narrative of over 150 historically significant anatomy books published in Europe, the Middle East, China, and Japan.

This treasure-trove of stories unfolds, including the transition of anatomy from philosophy to empirical science, challenges to authority and new discoveries, the establishment of dissection theaters, the problem of grave robbers and the enactment of laws related to dissection, the development of artistic and graphic anatomical drawings and printing, and controversies over plagiarism.

Immerse yourself in the world of anatomists with these incredibly detailed, vivid, and beautiful anatomical illustrations.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Opening remarks

Chapter 1: Anatomy of the Ancient World

3000 BC - 1300 AD

Chapter 2: Medieval Anatomy

1301 ~ 1500

Chapter 3 Anatomy in the Renaissance

1501 ~ 1600

Chapter 4: The Age of the Microscope

1601 ~ 1700

Chapter 5: The Age of Enlightenment

1701 ~ 1800

Chapter 6: The Age of Invention

1801 ~ 1900

The Future of Anatomy

Book list

Image source

Search

Chapter 1: Anatomy of the Ancient World

3000 BC - 1300 AD

Chapter 2: Medieval Anatomy

1301 ~ 1500

Chapter 3 Anatomy in the Renaissance

1501 ~ 1600

Chapter 4: The Age of the Microscope

1601 ~ 1700

Chapter 5: The Age of Enlightenment

1701 ~ 1800

Chapter 6: The Age of Invention

1801 ~ 1900

The Future of Anatomy

Book list

Image source

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

When first deciphered in 1930, the Edwin Smith Papyrus was found to contain the first known use of anatomical terms, including a hieroglyph for brain (literally 'skull offal').

This papyrus describes various parts of the brain and explains the symptoms that appear in the body when the head is injured.

It is currently the most important artifact among the many collections of the New York Academy of Medicine.

--- p.21

Through this series of events, Western Europe entered the so-called Dark Ages.

As the solid foundation of Roman civilization disappeared and the arts and sciences declined, the center of intellectual activity moved east to Constantinople.

There too, Galen influenced Islamic thought through the Eastern Roman Empire.

Immediately after Galen's death, and in the centuries that followed, many of his writings were translated into Arabic, Persian, and Syriac.

At a time when science in the Western world was retreating into the philosophical study of ancient texts, interest in anatomy was raging in the Middle East.

--- p.44~45

Some historians argue that although Mondino did perform dissections, such public demonstrations were not usually performed by anatomists themselves.

The anatomist would go up on stage and explain the dissection process verbally, usually reading aloud from a book like a narrator in a play to help the audience understand.

A public dissection usually involves three people: the lector (Latin for reader), who sits high up and holds a book to explain the anatomy;

A sectorer (meaning a person who cuts) is responsible for the actual incision and removal.

The ostensor, like a teacher in front of a blackboard, holds a pointed stick and points to the parts the lecturer is explaining, focusing people's attention.

--- p.72

Guido's illustrations contributed to the understanding of his and Mondino's texts, but they certainly did not rank with Leonardo da Vinci's.

Although he was a man of distinction in many fields, he was not an artist, and the perspective in the image of him removing the skullcap from the head of a beheaded prisoner is disastrous.

It's like a child drawing an egg in an egg cup on the breakfast table.

However, the cover was shown from the side rather than the top of the head, and the cranial suture, the junction of the two plates at the crown, was depicted as a cracked egg.

--- p.77~81

Anatomists sought scientific truth about body organs and systems, while artists longed for truth in portraiture.

Renaissance painters and sculptors were more interested in the influence of anatomy on human appearance.

For example, I thought that understanding the arrangement of arm muscles would help me draw human gestures better.

Knowledge of the skeleton greatly helped in vividly expressing the movements and postures of dramatic scenes.

(

--- p.126

Beginning with the easily refuted claim that the human lower jaw is divided into two like that of other animals, Fabrica corrected more than 300 of Galen's errors.

He also corrected the common belief that men have fewer ribs than women because God created women by taking an extra rib from the first man in the beginning.

This influenced the relationship between the Christian church and anatomy, as the rib story was important to biblical mythology and the church's belief in the superiority of men over women.

--- p.155

The dissected man and woman are in a minimalist landscape.

This background displays eye-catching objects such as riverboats and taxonomically accurate depictions of plants, while keeping the viewer's gaze focused on the body.

Areas where skin is peeled back and organs are exposed, such as the area around the female reproductive organs, are artistically depicted as if flower petals are opening, and sleeping babies are shown holding their skin up as if pulling a blanket.

Even the skeleton has its skin peeled away to reveal its interior.

--- p.214

To the book-buying public, microscopic anatomy was merely a novelty, but anatomists gradually realized its limitless potential.

Jan Swammerdam (1637-1680), a Dutch graduate student at Leiden University, was a pioneer in this field.

He studied the life history of insects early on, and his book Bybel der natuure, published in 1737, long after his death, was a comprehensive book on insect anatomy based on dissection and microscopic observation.

He saw the supremacy of God even in the smallest creatures, and he regarded his studies as a tribute to the wonders of God.

--- p.222~223

To overcome this unpleasant situation, in 1752 the British government enacted the Murder Act and attempted public dissections, in which the bodies of executed murderers were stabbed again.

After the 'official' dissection at the execution site, it became customary to transport the body to a medical school for further dissection.

The purpose of this law was twofold.

The goal was to create public aversion to dissection, thereby deterring crime and providing more corpses for anatomists.

--- p.272

In 1774, they published a Japanese translation of Kulmus's "Anatomical Diagram" as a book titled "Kaite Shinsho".

This book borrows illustrations not only from Coolmus' original but also from several anatomy books.

One of them was Juan Valverde's History of the Constitution of the Human Body (1556), which also 'borrowed' its illustrations from Vesalius' Fabrica.

Some of the illustrations were first published in Hubert Bidlow's Anatomy of the Human Body (1685).

It was a remarkable development compared to the 『Hash Edition』 published just two years ago.

While Kawaguchi Shinnin's anatomical drawings were reminiscent of those of Kajiwara Shozen from 400 years ago, the Kaitai Shinsho boasted 18th-century realism and precise detail.

It was of great significance that a Dutch book was translated into Japanese.

Japan's isolationist policy lasted until 1869, but Western anatomy was one of the first sciences to break through the barrier.

--- p.297

The biggest problem that has plagued anatomy teachers and students for a very long time has been the rapid decomposition of corpses.

So, dissection classes could only be held in the winter when the weather was cold.

Therefore, the invention that contributed most to the advancement of anatomy was refrigeration.

Although each organ or other specimen could be preserved in alcohol, it was not realistically possible to dispose of the entire body.

Although Ferdinand Carré in France and Karl von Linde in Germany studied refrigeration techniques in the 1860s, the first freezing methods used in anatomy were much older.

This papyrus describes various parts of the brain and explains the symptoms that appear in the body when the head is injured.

It is currently the most important artifact among the many collections of the New York Academy of Medicine.

--- p.21

Through this series of events, Western Europe entered the so-called Dark Ages.

As the solid foundation of Roman civilization disappeared and the arts and sciences declined, the center of intellectual activity moved east to Constantinople.

There too, Galen influenced Islamic thought through the Eastern Roman Empire.

Immediately after Galen's death, and in the centuries that followed, many of his writings were translated into Arabic, Persian, and Syriac.

At a time when science in the Western world was retreating into the philosophical study of ancient texts, interest in anatomy was raging in the Middle East.

--- p.44~45

Some historians argue that although Mondino did perform dissections, such public demonstrations were not usually performed by anatomists themselves.

The anatomist would go up on stage and explain the dissection process verbally, usually reading aloud from a book like a narrator in a play to help the audience understand.

A public dissection usually involves three people: the lector (Latin for reader), who sits high up and holds a book to explain the anatomy;

A sectorer (meaning a person who cuts) is responsible for the actual incision and removal.

The ostensor, like a teacher in front of a blackboard, holds a pointed stick and points to the parts the lecturer is explaining, focusing people's attention.

--- p.72

Guido's illustrations contributed to the understanding of his and Mondino's texts, but they certainly did not rank with Leonardo da Vinci's.

Although he was a man of distinction in many fields, he was not an artist, and the perspective in the image of him removing the skullcap from the head of a beheaded prisoner is disastrous.

It's like a child drawing an egg in an egg cup on the breakfast table.

However, the cover was shown from the side rather than the top of the head, and the cranial suture, the junction of the two plates at the crown, was depicted as a cracked egg.

--- p.77~81

Anatomists sought scientific truth about body organs and systems, while artists longed for truth in portraiture.

Renaissance painters and sculptors were more interested in the influence of anatomy on human appearance.

For example, I thought that understanding the arrangement of arm muscles would help me draw human gestures better.

Knowledge of the skeleton greatly helped in vividly expressing the movements and postures of dramatic scenes.

(

--- p.126

Beginning with the easily refuted claim that the human lower jaw is divided into two like that of other animals, Fabrica corrected more than 300 of Galen's errors.

He also corrected the common belief that men have fewer ribs than women because God created women by taking an extra rib from the first man in the beginning.

This influenced the relationship between the Christian church and anatomy, as the rib story was important to biblical mythology and the church's belief in the superiority of men over women.

--- p.155

The dissected man and woman are in a minimalist landscape.

This background displays eye-catching objects such as riverboats and taxonomically accurate depictions of plants, while keeping the viewer's gaze focused on the body.

Areas where skin is peeled back and organs are exposed, such as the area around the female reproductive organs, are artistically depicted as if flower petals are opening, and sleeping babies are shown holding their skin up as if pulling a blanket.

Even the skeleton has its skin peeled away to reveal its interior.

--- p.214

To the book-buying public, microscopic anatomy was merely a novelty, but anatomists gradually realized its limitless potential.

Jan Swammerdam (1637-1680), a Dutch graduate student at Leiden University, was a pioneer in this field.

He studied the life history of insects early on, and his book Bybel der natuure, published in 1737, long after his death, was a comprehensive book on insect anatomy based on dissection and microscopic observation.

He saw the supremacy of God even in the smallest creatures, and he regarded his studies as a tribute to the wonders of God.

--- p.222~223

To overcome this unpleasant situation, in 1752 the British government enacted the Murder Act and attempted public dissections, in which the bodies of executed murderers were stabbed again.

After the 'official' dissection at the execution site, it became customary to transport the body to a medical school for further dissection.

The purpose of this law was twofold.

The goal was to create public aversion to dissection, thereby deterring crime and providing more corpses for anatomists.

--- p.272

In 1774, they published a Japanese translation of Kulmus's "Anatomical Diagram" as a book titled "Kaite Shinsho".

This book borrows illustrations not only from Coolmus' original but also from several anatomy books.

One of them was Juan Valverde's History of the Constitution of the Human Body (1556), which also 'borrowed' its illustrations from Vesalius' Fabrica.

Some of the illustrations were first published in Hubert Bidlow's Anatomy of the Human Body (1685).

It was a remarkable development compared to the 『Hash Edition』 published just two years ago.

While Kawaguchi Shinnin's anatomical drawings were reminiscent of those of Kajiwara Shozen from 400 years ago, the Kaitai Shinsho boasted 18th-century realism and precise detail.

It was of great significance that a Dutch book was translated into Japanese.

Japan's isolationist policy lasted until 1869, but Western anatomy was one of the first sciences to break through the barrier.

--- p.297

The biggest problem that has plagued anatomy teachers and students for a very long time has been the rapid decomposition of corpses.

So, dissection classes could only be held in the winter when the weather was cold.

Therefore, the invention that contributed most to the advancement of anatomy was refrigeration.

Although each organ or other specimen could be preserved in alcohol, it was not realistically possible to dispose of the entire body.

Although Ferdinand Carré in France and Karl von Linde in Germany studied refrigeration techniques in the 1860s, the first freezing methods used in anatomy were much older.

--- p.353

Publisher's Review

“The body is ourselves.”

Anatomist explores the world beneath the skin

A History of Human Exploration Through Anatomy Books

How were the internal workings of our bodies discovered? How were the names of each organ given? From ancient Egypt to the Renaissance, modern times, and the 21st century, the books that have filled anatomists' libraries for approximately 5,000 years contain a history of understanding the human body, artistic techniques, and social change.

"The Anatomist's World" unravels the vast narrative of over 150 historically significant anatomy books published in Europe, the Middle East, China, and Japan.

Immerse yourself in the world of anatomists with these incredibly detailed, vivid, and beautiful anatomical illustrations.

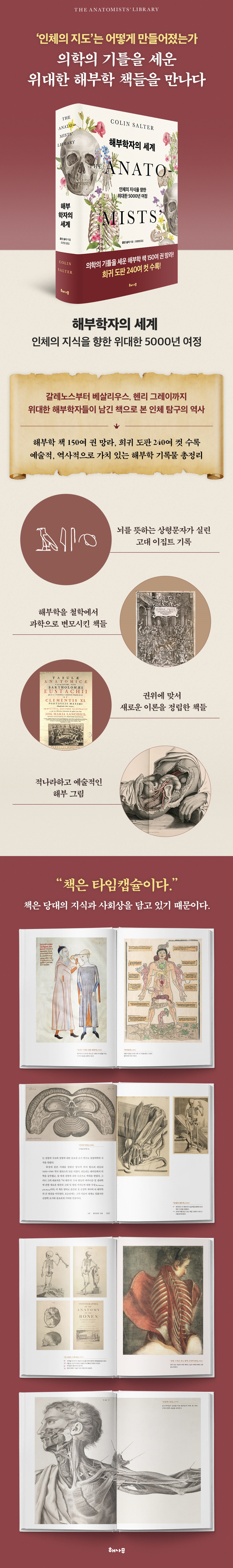

How was the 'map of the human body' created?

Meet the great anatomy books that laid the foundation for medicine.

When we are injured or sick and unable to move, we are reminded of the importance of our body.

It is perhaps no wonder that the body has captivated the human mind for thousands of years, since ancient times before Christ.

There was also a philosophical question about whether the soul resided in the head or the heart, but fundamentally, it is because you cannot treat the human body without understanding it.

"The World of Anatomists" is a book that compiles the achievements of great researchers through anatomy books that have had a profound impact on the development of medicine.

The oldest extant anatomical record is the Edwin Smith Papyrus, an ancient Egyptian document from 3000 BC.

This papyrus was a practical book centered on observation and practice, rather than magic or superstition, and it was found that anatomical terms were first used in it.

Galen's theories, including the humoral theory, dominated Western medicine for a full 1,300 years, from the 2nd to the 14th centuries.

Vesalius's Fabrica, published in the 16th century, corrected over 300 of Galen's errors and became a bestseller at the time, marking the beginning of the development of modern anatomy.

The best-selling anatomy textbook, Gray's Anatomy, is a living anatomy textbook that has been revised for 42 times since its first edition was published in 1858.

This book vividly and engagingly conveys humanity's journey toward knowledge of the human body, including the transition of anatomy from philosophy to empirical science, challenges to authority and new discoveries, the establishment of dissection theaters, the problem of grave robbers and the enactment of laws related to dissection, the development of artistic and graphic anatomical drawings and printing, and controversies over plagiarism, through historically and artistically valuable illustrations.

Join the author as he delves into dusty books of the past.

You will discover a treasure trove of stories within it.

Includes over 150 anatomy books and over 240 rare illustrations.

A comprehensive compilation of historically and artistically valuable anatomical records.

Anatomy is one of the scientific fields in which illustrations are very important.

Throughout history, illustrations in anatomy books have played as important a role in conveying information as the text itself.

Anatomists needed the help of excellent illustrators, and in that sense, illustrators can be said to have contributed to the development of anatomy.

This book covers not only the development of medical knowledge, but also the evolution of anatomy books and illustrations.

It includes over 150 anatomy books and over 240 rare plates, and covers artists' interest in anatomy, changes in illustrations, title page illustrations, the popularization of flap books (a device that allows one to lift the cover to reveal hidden pictures), plagiarism controversies, and the development of printing technology.

The illustrations in Guido da Vigevano's 14th-century book Anatomy for Philip VII (1345) are two-dimensional planes without perspective.

On the other hand, Leonardo da Vinci's anatomical drawings are of a very high standard, using light and shade, various shading techniques, and pale colors.

Da Vinci's anatomical writings were discovered 400 years after his death, but he possessed a profound anatomical knowledge thanks to his remarkable observation and insight.

Vesalius's Fabrica (1543), a bestseller in the 16th century, also played a role in popularizing flap books, and its popularity also led to plagiarism disputes.

Pictures of human body dissections are, by their very nature, very detailed and graphic, yet they also possess artistic value.

In Giulio Caseri's Anatomical Drawings (1627), the model's body is shown in various positions, showing the muscles of the arms, legs, and back, while in William Chesledon's Osteographia (1733), the skeleton of an 18-month-old child holds an adult femur for comparison.

Joseph McLeaf, who illustrated Richard Quine's Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body (1844), displayed outstanding artistic skill, accurately and realistically depicting areas of interest while treating the surrounding areas with simple drawings to highlight the anatomical parts.

Rich in historically and artistically valuable illustrations, this book adds visual enjoyment and brings the history of anatomy to life.

Let's take a look at human anatomy illustrations that you won't find in modern anatomy textbooks.

You may discover new elements of enjoyment in anatomy.

How did anatomy develop and relate to the world?

From treating wounded soldiers to embalming corpses

“Books are time capsules.” This is because books contain the thoughts and social conditions of the time.

If we were to collect the anatomy books that once sat in an anatomist's study and organize them chronologically, it could become a narrative of humanity's journey toward knowledge of the human body.

This book illuminates how anatomy relates to the world through anatomy books.

The first application of anatomy was on the ancient battlefield, and during times of war in human history, anatomy books were published to treat the wounds of wounded soldiers.

During the 17th to 19th centuries, when anatomy was popular, there was a shortage of corpses for dissection, which led to the rise of grave robbers, a social problem that led to the enactment of laws related to dissection.

The 17th-century anatomist Marcello Malpighi became the first person to donate a body for dissection when he left a will requesting that his body be autopsied.

The invention of the microscope allowed the examination of capillaries, which confirmed William Harvey's closed circulatory system hypothesis, and the invention of the endoscope, anesthesia, refrigeration, and embalming contributed to the study of anatomy.

The author, fascinated by the work of delving into the history of how each field reached its current position, discovers medical discoveries and anecdotes related to anatomy books in this book, and reads the flow of 5,000 years of anatomy history in one breath.

If we learn about the history that led to the knowledge about the human body that we take for granted today, we will be able to appreciate anatomy books and look at them in a new way.

Anatomist explores the world beneath the skin

A History of Human Exploration Through Anatomy Books

How were the internal workings of our bodies discovered? How were the names of each organ given? From ancient Egypt to the Renaissance, modern times, and the 21st century, the books that have filled anatomists' libraries for approximately 5,000 years contain a history of understanding the human body, artistic techniques, and social change.

"The Anatomist's World" unravels the vast narrative of over 150 historically significant anatomy books published in Europe, the Middle East, China, and Japan.

Immerse yourself in the world of anatomists with these incredibly detailed, vivid, and beautiful anatomical illustrations.

How was the 'map of the human body' created?

Meet the great anatomy books that laid the foundation for medicine.

When we are injured or sick and unable to move, we are reminded of the importance of our body.

It is perhaps no wonder that the body has captivated the human mind for thousands of years, since ancient times before Christ.

There was also a philosophical question about whether the soul resided in the head or the heart, but fundamentally, it is because you cannot treat the human body without understanding it.

"The World of Anatomists" is a book that compiles the achievements of great researchers through anatomy books that have had a profound impact on the development of medicine.

The oldest extant anatomical record is the Edwin Smith Papyrus, an ancient Egyptian document from 3000 BC.

This papyrus was a practical book centered on observation and practice, rather than magic or superstition, and it was found that anatomical terms were first used in it.

Galen's theories, including the humoral theory, dominated Western medicine for a full 1,300 years, from the 2nd to the 14th centuries.

Vesalius's Fabrica, published in the 16th century, corrected over 300 of Galen's errors and became a bestseller at the time, marking the beginning of the development of modern anatomy.

The best-selling anatomy textbook, Gray's Anatomy, is a living anatomy textbook that has been revised for 42 times since its first edition was published in 1858.

This book vividly and engagingly conveys humanity's journey toward knowledge of the human body, including the transition of anatomy from philosophy to empirical science, challenges to authority and new discoveries, the establishment of dissection theaters, the problem of grave robbers and the enactment of laws related to dissection, the development of artistic and graphic anatomical drawings and printing, and controversies over plagiarism, through historically and artistically valuable illustrations.

Join the author as he delves into dusty books of the past.

You will discover a treasure trove of stories within it.

Includes over 150 anatomy books and over 240 rare illustrations.

A comprehensive compilation of historically and artistically valuable anatomical records.

Anatomy is one of the scientific fields in which illustrations are very important.

Throughout history, illustrations in anatomy books have played as important a role in conveying information as the text itself.

Anatomists needed the help of excellent illustrators, and in that sense, illustrators can be said to have contributed to the development of anatomy.

This book covers not only the development of medical knowledge, but also the evolution of anatomy books and illustrations.

It includes over 150 anatomy books and over 240 rare plates, and covers artists' interest in anatomy, changes in illustrations, title page illustrations, the popularization of flap books (a device that allows one to lift the cover to reveal hidden pictures), plagiarism controversies, and the development of printing technology.

The illustrations in Guido da Vigevano's 14th-century book Anatomy for Philip VII (1345) are two-dimensional planes without perspective.

On the other hand, Leonardo da Vinci's anatomical drawings are of a very high standard, using light and shade, various shading techniques, and pale colors.

Da Vinci's anatomical writings were discovered 400 years after his death, but he possessed a profound anatomical knowledge thanks to his remarkable observation and insight.

Vesalius's Fabrica (1543), a bestseller in the 16th century, also played a role in popularizing flap books, and its popularity also led to plagiarism disputes.

Pictures of human body dissections are, by their very nature, very detailed and graphic, yet they also possess artistic value.

In Giulio Caseri's Anatomical Drawings (1627), the model's body is shown in various positions, showing the muscles of the arms, legs, and back, while in William Chesledon's Osteographia (1733), the skeleton of an 18-month-old child holds an adult femur for comparison.

Joseph McLeaf, who illustrated Richard Quine's Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body (1844), displayed outstanding artistic skill, accurately and realistically depicting areas of interest while treating the surrounding areas with simple drawings to highlight the anatomical parts.

Rich in historically and artistically valuable illustrations, this book adds visual enjoyment and brings the history of anatomy to life.

Let's take a look at human anatomy illustrations that you won't find in modern anatomy textbooks.

You may discover new elements of enjoyment in anatomy.

How did anatomy develop and relate to the world?

From treating wounded soldiers to embalming corpses

“Books are time capsules.” This is because books contain the thoughts and social conditions of the time.

If we were to collect the anatomy books that once sat in an anatomist's study and organize them chronologically, it could become a narrative of humanity's journey toward knowledge of the human body.

This book illuminates how anatomy relates to the world through anatomy books.

The first application of anatomy was on the ancient battlefield, and during times of war in human history, anatomy books were published to treat the wounds of wounded soldiers.

During the 17th to 19th centuries, when anatomy was popular, there was a shortage of corpses for dissection, which led to the rise of grave robbers, a social problem that led to the enactment of laws related to dissection.

The 17th-century anatomist Marcello Malpighi became the first person to donate a body for dissection when he left a will requesting that his body be autopsied.

The invention of the microscope allowed the examination of capillaries, which confirmed William Harvey's closed circulatory system hypothesis, and the invention of the endoscope, anesthesia, refrigeration, and embalming contributed to the study of anatomy.

The author, fascinated by the work of delving into the history of how each field reached its current position, discovers medical discoveries and anecdotes related to anatomy books in this book, and reads the flow of 5,000 years of anatomy history in one breath.

If we learn about the history that led to the knowledge about the human body that we take for granted today, we will be able to appreciate anatomy books and look at them in a new way.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: September 30, 2024

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 416 pages | 740g | 153*224*30mm

- ISBN13: 9791164052752

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)