action

|

Description

Book Introduction

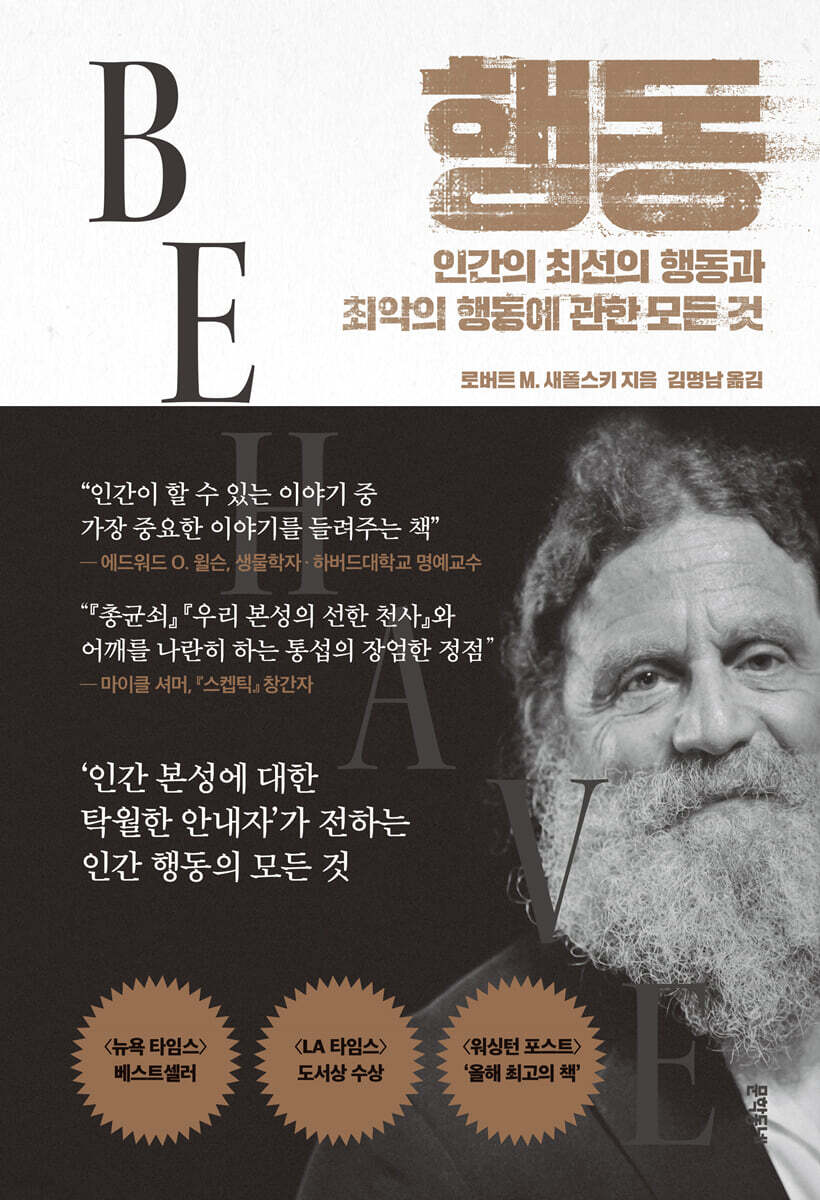

No book has ever dealt with human violence, aggression, and competition better than this! A heroic insight into the duality of our nature: its "special cruelty" and its "rare altruism"! “Even Darwin would have been thrilled to read this book!” - [New York Times] Robert M., one of the world's leading neuroscientists, whom social psychologist Jonathan Haidt called "a brilliant guide to human nature" and neurologist Oliver Sacks called "the greatest science writer of our time." Sapolsky's book, "Action," has finally been published in Korea. This masterpiece, which took more than 10 years to write, has garnered attention and interest from the public and academic circles since its publication, becoming a New York Times bestseller, winning the LA Times Book Award, and being selected as one of the Washington Post's "Best Books of the Year." It is a "dazzling attempt to outline the science of human behavior" and a "clear guide to the complex world of human nature." The central question that runs through this book is, “Why do humans sometimes treat each other with unspeakable horrors, and at other times with unparalleled generosity?” To explore the duality of our nature—our "special cruelty" and our "rare altruism"—the author crosses a wide range of academic disciplines, from neurobiology and brain science to genetics, sociobiology, and psychology, providing a comprehensive overview of cutting-edge research. And based on that understanding, it answers some of the most profound and contradictory questions about human society: tribalism and xenophobia, hierarchy and competition, morality and free will, war and peace. This is why Michael Shermer, founder of the world-renowned science journal Skeptic, praised this book Behavior as “a magnificent pinnacle of synthesis, on par with Guns, Germs, and Steel and The Better Angels of Our Nature,” and the New York Times commented, “Even Darwin would have been thrilled to read this book.” |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

introduction

Chapter 1.

action

Chapter 2.

1 second ago

Chapter 3.

A few seconds to a few minutes ago

Chapter 4.

A few hours to a few days ago

Chapter 5.

A few days to a few months ago

Chapter 6.

Adolescence, or hey, where did my frontal lobe go?

Chapter 7.

Back to the cradle, back to the womb

Chapter 8.

Go back to the moment when you were a fertilized egg

Chapter 9.

Hundreds to thousands of years ago

Chapter 10.

Evolution of behavior

Chapter 11.

Us and them

Chapter 12.

Hierarchy, obedience, resistance

Chapter 13.

Morality and doing the right thing, once you figure out what's right

Chapter 14.

Feeling, understanding, and alleviating the suffering of others

Chapter 15.

A metaphor that invites murder

Chapter 16.

Biology, the criminal justice system, and (while I'm at it) free will

Chapter 17.

War and Peace

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

Appendix 1.

Introduction to Neuroscience

Appendix 2.

Fundamentals of Endocrinology

Appendix 3.

The basics of protein

Abbreviations used in the state

main

Image source

Search

Chapter 1.

action

Chapter 2.

1 second ago

Chapter 3.

A few seconds to a few minutes ago

Chapter 4.

A few hours to a few days ago

Chapter 5.

A few days to a few months ago

Chapter 6.

Adolescence, or hey, where did my frontal lobe go?

Chapter 7.

Back to the cradle, back to the womb

Chapter 8.

Go back to the moment when you were a fertilized egg

Chapter 9.

Hundreds to thousands of years ago

Chapter 10.

Evolution of behavior

Chapter 11.

Us and them

Chapter 12.

Hierarchy, obedience, resistance

Chapter 13.

Morality and doing the right thing, once you figure out what's right

Chapter 14.

Feeling, understanding, and alleviating the suffering of others

Chapter 15.

A metaphor that invites murder

Chapter 16.

Biology, the criminal justice system, and (while I'm at it) free will

Chapter 17.

War and Peace

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

Appendix 1.

Introduction to Neuroscience

Appendix 2.

Fundamentals of Endocrinology

Appendix 3.

The basics of protein

Abbreviations used in the state

main

Image source

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

This book will examine the biology of violence, aggression, and competition.

We will examine the actions and impulses behind such phenomena, the actions of individuals, groups, and nations, and when these actions are bad or good.

We will examine the many ways in which humans harm one another.

But at the same time, we will also look at ways in which people behave in the opposite way.

What can biology tell us about cooperation, alliances, reconciliation, empathy, and altruism?

--- From the "Preface"

There is no brain in the world that operates in a vacuum.

In just seconds or minutes, countless pieces of information flood our brains, influencing our prosocial or antisocial behavior.

As we have seen, the information available at this time can range from something as simple and one-dimensional as the color of a shirt to something as complex and subtle as clues about ideology.

Moreover, the brain constantly receives interoceptive information.

The most important thing is that most of this diverse information is subconscious.

The ultimate point of this chapter is this:

In the minutes before we decide on a very important action, we are far less rational and autonomous decision makers than we think.

--- Chapter 3.

From a few seconds to a few minutes ago

Other studies have shown that giving subjects oxytocin makes them rate people's faces as more trustworthy and more trustworthy in economic games (oxytocin had no effect when subjects thought they were playing against a computer, suggesting that oxytocin is a social behavior).

This increased trust was an interesting phenomenon.

Typically, if another player behaves dishonestly in a game, subjects are less likely to trust that opponent in subsequent rounds.

In contrast, subjects who received oxytocin did not exhibit this behavioral change.

In scientific terms, “oxytocin immunized investors against betrayal.”

To put it bluntly, oxytocin makes people irrational and gullible fools.

To put it like an angel, oxytocin makes people turn the other cheek.

--- Chapter 4.

From a few hours to a few days ago

Two very important implications follow from this.

First, the area of the adult brain that is most formed during adolescence is the prefrontal cortex.

Second, we cannot understand anything about adolescence without considering the context of delayed maturation of this prefrontal lobe.

The fact that by adolescence, the limbic system, autonomic nervous system, and endocrine system are already fully operational, while the prefrontal cortex is only just beginning to fiddle with the assembly instructions, is precisely why adolescence is such a desperate, wonderful, stupid, impulsive, inspiring, destructive, self-destructive, altruistic, selfish, difficult, and world-changing time.

Think about it.

Adolescence and early adulthood are the times when we are most likely to kill, be killed, leave home forever, invent a new art form, help overthrow a dictator, ethnically cleanse a town, devote ourselves to others, become addicted, marry an outsider, revolutionize physics, show off our terrible fashion sense, break our necks in the middle of a game, dedicate our lives to God, and rob old ladies.

It is also easy to believe that human history is destined to converge on this very moment, that now is the most crucial time, full of danger and opportunity, and so much to do that we must intervene and change things.

In short, adolescence is the time in our lives when we take the most risks, seek out new things, and connect with our peers.

And all of this is due to the immature frontal cortex.

--- Chapter 6.

From "Adolescence, or Hey, Where Did My Frontal Cortex Go?"

There are many unique aspects of human hierarchy, but if we were to name the most unique and novel feature, it would be the act of appointing and electing leaders.

As I mentioned earlier, old primatology comically mistook high rank for 'leadership status'.

But the alpha male of the baboon is not the leader.

They are just beings who take the best part of anything.

And although the baboons do follow an older, more knowledgeable female when they go out to forage in the morning, if you look closely, she doesn't "lead" the group; she just "goes."

But humans establish leaders based on a peculiar concept of the public good.

(...) An even newer phenomenon is that humans choose their leaders directly.

Whether it's sitting around a campfire and applauding to elect a chieftain, or ending a three-year presidential campaign with the bizarre act of voting in the Electoral College.

How do we choose our leaders?

One of the conscious factors we often use in our decision-making is voting based on a candidate's experience or abilities rather than their stance on a particular issue.

This is a very common phenomenon.

In one study, candidates whom subjects chose as appearing more competent actually won 68% of the time in the actual election.

We also consciously choose candidates based on issues that may be irrelevant to the issue at hand (like electing a county dog catcher assistant by considering candidates' views on Pakistan's drone warfare).

--- 「Chapter 12.

From “Hierarchy, Obedience, Resistance”

When people see someone else's hand being pricked with a needle, they also feel a sensorimotor response in their own hand.

At this time, the reaction is stronger if the other person is of the same race as oneself, and this phenomenon is more pronounced when the person has a strong implicit in-group bias.

(...)

This phenomenon of the scope of empathy varying depending on the category of the other person also occurs depending on socioeconomic status, but the pattern is asymmetrical.

What this means is that rich people generally suck when it comes to empathy and compassion.

A series of studies conducted by Dacher Keltner of the University of California, Berkeley, uncovered this fact.

According to him, when looking across the entire range of socioeconomic status, on average, wealthier subjects reported feeling less empathy toward those in distress and were also less likely to exhibit actual sympathetic behavior.

Moreover, the wealthier the subjects, the less able they were to recognize the emotions of others, the more greedy they behaved in the experimental setting, and the more likely they were to cheat or steal.

--- Chapter 14.

From “Feeling, Understanding, and Relief of Others’ Pain”

Dehumanization, pseudo-speciation.

It is a tool of hate mongers.

Describing them as disgusting.

Describing them as rats, as cancer cells, as beings that are becoming a different species.

Depicting them as stinking beings, living in a state of disorder that no normal human being can endure.

Describing them as shit.

If you can successfully confuse the insular cortex of your followers with the real and the metaphorical, you're 99% on your way to achieving your goal.

We will examine the actions and impulses behind such phenomena, the actions of individuals, groups, and nations, and when these actions are bad or good.

We will examine the many ways in which humans harm one another.

But at the same time, we will also look at ways in which people behave in the opposite way.

What can biology tell us about cooperation, alliances, reconciliation, empathy, and altruism?

--- From the "Preface"

There is no brain in the world that operates in a vacuum.

In just seconds or minutes, countless pieces of information flood our brains, influencing our prosocial or antisocial behavior.

As we have seen, the information available at this time can range from something as simple and one-dimensional as the color of a shirt to something as complex and subtle as clues about ideology.

Moreover, the brain constantly receives interoceptive information.

The most important thing is that most of this diverse information is subconscious.

The ultimate point of this chapter is this:

In the minutes before we decide on a very important action, we are far less rational and autonomous decision makers than we think.

--- Chapter 3.

From a few seconds to a few minutes ago

Other studies have shown that giving subjects oxytocin makes them rate people's faces as more trustworthy and more trustworthy in economic games (oxytocin had no effect when subjects thought they were playing against a computer, suggesting that oxytocin is a social behavior).

This increased trust was an interesting phenomenon.

Typically, if another player behaves dishonestly in a game, subjects are less likely to trust that opponent in subsequent rounds.

In contrast, subjects who received oxytocin did not exhibit this behavioral change.

In scientific terms, “oxytocin immunized investors against betrayal.”

To put it bluntly, oxytocin makes people irrational and gullible fools.

To put it like an angel, oxytocin makes people turn the other cheek.

--- Chapter 4.

From a few hours to a few days ago

Two very important implications follow from this.

First, the area of the adult brain that is most formed during adolescence is the prefrontal cortex.

Second, we cannot understand anything about adolescence without considering the context of delayed maturation of this prefrontal lobe.

The fact that by adolescence, the limbic system, autonomic nervous system, and endocrine system are already fully operational, while the prefrontal cortex is only just beginning to fiddle with the assembly instructions, is precisely why adolescence is such a desperate, wonderful, stupid, impulsive, inspiring, destructive, self-destructive, altruistic, selfish, difficult, and world-changing time.

Think about it.

Adolescence and early adulthood are the times when we are most likely to kill, be killed, leave home forever, invent a new art form, help overthrow a dictator, ethnically cleanse a town, devote ourselves to others, become addicted, marry an outsider, revolutionize physics, show off our terrible fashion sense, break our necks in the middle of a game, dedicate our lives to God, and rob old ladies.

It is also easy to believe that human history is destined to converge on this very moment, that now is the most crucial time, full of danger and opportunity, and so much to do that we must intervene and change things.

In short, adolescence is the time in our lives when we take the most risks, seek out new things, and connect with our peers.

And all of this is due to the immature frontal cortex.

--- Chapter 6.

From "Adolescence, or Hey, Where Did My Frontal Cortex Go?"

There are many unique aspects of human hierarchy, but if we were to name the most unique and novel feature, it would be the act of appointing and electing leaders.

As I mentioned earlier, old primatology comically mistook high rank for 'leadership status'.

But the alpha male of the baboon is not the leader.

They are just beings who take the best part of anything.

And although the baboons do follow an older, more knowledgeable female when they go out to forage in the morning, if you look closely, she doesn't "lead" the group; she just "goes."

But humans establish leaders based on a peculiar concept of the public good.

(...) An even newer phenomenon is that humans choose their leaders directly.

Whether it's sitting around a campfire and applauding to elect a chieftain, or ending a three-year presidential campaign with the bizarre act of voting in the Electoral College.

How do we choose our leaders?

One of the conscious factors we often use in our decision-making is voting based on a candidate's experience or abilities rather than their stance on a particular issue.

This is a very common phenomenon.

In one study, candidates whom subjects chose as appearing more competent actually won 68% of the time in the actual election.

We also consciously choose candidates based on issues that may be irrelevant to the issue at hand (like electing a county dog catcher assistant by considering candidates' views on Pakistan's drone warfare).

--- 「Chapter 12.

From “Hierarchy, Obedience, Resistance”

When people see someone else's hand being pricked with a needle, they also feel a sensorimotor response in their own hand.

At this time, the reaction is stronger if the other person is of the same race as oneself, and this phenomenon is more pronounced when the person has a strong implicit in-group bias.

(...)

This phenomenon of the scope of empathy varying depending on the category of the other person also occurs depending on socioeconomic status, but the pattern is asymmetrical.

What this means is that rich people generally suck when it comes to empathy and compassion.

A series of studies conducted by Dacher Keltner of the University of California, Berkeley, uncovered this fact.

According to him, when looking across the entire range of socioeconomic status, on average, wealthier subjects reported feeling less empathy toward those in distress and were also less likely to exhibit actual sympathetic behavior.

Moreover, the wealthier the subjects, the less able they were to recognize the emotions of others, the more greedy they behaved in the experimental setting, and the more likely they were to cheat or steal.

--- Chapter 14.

From “Feeling, Understanding, and Relief of Others’ Pain”

Dehumanization, pseudo-speciation.

It is a tool of hate mongers.

Describing them as disgusting.

Describing them as rats, as cancer cells, as beings that are becoming a different species.

Depicting them as stinking beings, living in a state of disorder that no normal human being can endure.

Describing them as shit.

If you can successfully confuse the insular cortex of your followers with the real and the metaphorical, you're 99% on your way to achieving your goal.

--- Chapter 15.

From "Metaphors that Invoke Murder"

From "Metaphors that Invoke Murder"

Publisher's Review

No book has ever dealt with human violence, aggression, and competition better than this!

A heroic insight into the duality of our nature: its "special cruelty" and its "rare altruism"!

“Even Darwin would have been thrilled to read this book!” - The New York Times

Robert M., one of the world's leading neuroscientists, whom social psychologist Jonathan Haidt called "a brilliant guide to human nature" and neurologist Oliver Sacks called "the greatest science writer of our time."

Sapolsky's book, "Action," has finally been published in Korea.

This masterpiece, which took more than 10 years to write, has garnered attention and interest from the public and academic circles since its publication, becoming a New York Times bestseller, winning the LA Times Book Award, and being selected as one of the Washington Post's "Best Books of the Year." It is a "dazzling attempt to outline the science of human behavior" and a "clear guide to the complex world of human nature."

The central question that runs through this book is, “Why do humans sometimes treat each other with unspeakable horrors, and at other times with unparalleled generosity?”

To explore the duality of our nature—our "special cruelty" and our "rare altruism"—the author crosses a wide range of academic disciplines, from neurobiology and brain science to genetics, sociobiology, and psychology, providing a comprehensive overview of cutting-edge research.

And based on that understanding, it answers some of the most profound and contradictory questions about human society: tribalism and xenophobia, hierarchy and competition, morality and free will, war and peace.

This is why Michael Shermer, founder of the world-renowned science journal Skeptic, praised this book Behavior as “a magnificent pinnacle of synthesis, on par with Guns, Germs, and Steel and The Better Angels of Our Nature,” and the New York Times commented, “Even Darwin would have been thrilled to read this book.”

“The central argument of this book is that we do not hate violence.

What we hate and fear is the wrong kind of violence, violence in the wrong context.

Because violence in the right context is different.

(...) This ambiguity—that the act of pulling the trigger of a gun can be either a vicious act of aggression or an act of self-sacrificing love—is what makes violence so difficult to understand.

This book will examine the biology of violence, aggression, and competition.

We will examine the actions and impulses behind such phenomena, the actions of individuals, groups, and nations, and when these actions are bad or good.

We will examine the many ways in which humans harm one another.

But at the same time, we will also look at ways in which people behave in the opposite way.

“What can biology tell us about cooperation, alliances, reconciliation, empathy, and altruism?” _From the Preface

Everything You Need to Know About Human Behavior from a "Superb Guide to Human Nature"

“A book that tells the most important story a human being can tell.”

- Edward O.

Wilson, biologist and professor emeritus at Harvard University

"A majestic pinnacle of synthesis, on par with Guns, Germs, and Steel and The Better Angels of Our Nature."

- Michael Shermer, founder of Skeptic

Why on earth do we do 'that'?

Sapolsky examines this question from multiple angles, defying all academic disciplines to faithfully answer it in a way only he can.

He presents a composition that is not only interesting but also follows a compelling internal logic.

First, we look at the factors that influenced a person's reaction at the moment of someone's action, and then we go back in time (from a second ago, to a few hours ago, to a few days ago, to the time when the person was a fertilized egg) and finally we look at the legacy left behind by our species' long evolutionary history.

The first half of the book, comprising chapters 1 through 10 of a total of 17, focuses on transcending the interdisciplinary boundaries of existing research.

'How do neurons and hormones interact?' 'Why are emotions an essential element of decision-making?' 'Why are adolescents more prone to violence than adults?' 'How do genes and culture influence each other?' We examine the influence of the brain, genes, hormones, childhood, cultural environment, evolution, and ecosystems on our aggression, violence, competitiveness, cooperation, altruism, empathy, and sense of belonging.

The scholarly depth and breadth of this book, built on Sapolsky's own research and extensive knowledge of neurobiology, genetics, and behavior, are truly astonishing.

“It tells the most important story that humans can tell,” said biologist Edward O.

This is why I find myself nodding in agreement with Wilson's comments.

Another strength of this book that cannot be overlooked is that it is 'fun'.

Wise, humane, and often downright funny, this book, "Action," by an author renowned for her profound writing and witty humor—so much so that the New York Times once said, "If you mixed Jane Goodall with a comedian, she'd write like Sapolsky." It's a heroic achievement in its own right.

# action

So, 'some' action occurred.

It might be a bad thing.

You pulled the trigger and shot an innocent person.

Maybe it's a good thing.

You pulled the trigger to attract the enemy's attention and save someone else.

Anyway, the important question here is this:

Why did that behavior occur?

# 1 second ago

The book begins with the dimension closest to us in time.

What was going on in that person's head just "one second" before they committed that action? What critical event occurred that second before that led to that prosocial or antisocial behavior? This is a question of neurobiology.

Here we see evidence that the limbic system plays a key role in emotional activity, which drives both the best and worst behaviors; that the prefrontal cortex, the most recently evolved part of the cortex that governs intellectual functions, controls behavioral regulation and constraints; that the amygdala plays a major role in fear and aggression; and that the dopamine system plays a role in reward and motivation.

“In one study, subjects were shown items they could purchase.

At this time, the degree of activation of the precuneus predicted well the likelihood that the subject would pay.

Then I told them the price.

If the price was lower than the subject was willing to pay, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for emotion, was activated.

When it was more expensive, the insular cortex, which is involved in disgust, was activated.

By combining this brain imaging data, they were able to predict whether the subject would buy the item or not.

In this typical mammal, the dopamine system encodes both good and bad surprises in a wide range of ways, and it constantly habituates them to yesterday's news.

But humans have something to add to this.

“The point is that we invent pleasures that are far more intense than any pleasure nature provides.” _〈Chapter 2.

From 1 second ago

# seconds to minutes ago ~ hours to days ago

Now let's look at a point a little further ahead.

What visual, auditory, and olfactory stimuli might have acted on his nervous system to trigger that behavior? And what hormones, hours or days prior, might have influenced his response to those stimuli? Expanding his perspective to this level, Sapolsky draws on not only neurobiology but also the sensory world surrounding us and endocrinology to explain "what" behavior.

This shows that sensory and interoceptive information can influence the brain and trigger behavior in seconds or minutes, and that sights, smells, stomach aches, word choices, and even more subtle cues can influence us unconsciously.

We also learn that testosterone, known as the aggression hormone, does not ‘invent’ aggression, and that oxytocin and vasopressin also reduce anxiety and stress, and promote cooperation and tolerance, but only in certain contexts (these hormones promote prosociality only toward ‘us’, but increase xenophobia when dealing with ‘them’).

“A beautiful study by Karsten Dudrö at the University of Amsterdam showed that oxytocin may not be really warm and pleasant.

First, the male subjects were divided into two teams.

Each subject decided how much of his own money he would contribute to the property shared with his teammates.

As always, oxytocin increased generosity at this time.

Next, the subjects played the prisoner's dilemma game with people from another team.

When the stakes were high and subjects were more motivated, oxytocin made them more likely to preemptively betray their partner.

In short, oxytocin increases prosociality toward people like us (such as teammates), but makes us more willing to be annoying toward others we perceive as a threat.

As Dudreux points out, oxytocin may have evolved to enhance our social capacity to better recognize who is on our side.” _〈Chapter 4.

From a few hours to a few days ago

# A few months ago - adolescence - childhood - fetus, and...

Sapolsky's questions continue.

How did the structural changes his nervous system underwent over the past few months affect his behavior? How did the adversity he experienced as a teenager, a child, and a fetus influence his adult life? What were the social pressures from his peers during his teenage years, the hormonal changes of his adolescence, his childhood home environment, his postnatal brain development, and the amount of maternal hormones supplied through the fetal bloodstream? What were the implications of his genes?

Finally, the author expands his perspective by asking how culture has influenced the groups to which individuals belong, and how ecological factors at work over the past thousands of years have shaped that culture.

And finally, we see the evolutionary factors that have been at work over the past millions of years.

nevertheless,

A journey of knowledge: from 'worst' to 'best', from 'despair' to 'hope'

The second half of the book, chapters 11 through 17, synthesizes the material covered in the first half and examines the areas of human behavior where the material most importantly applies.

First, Sapolsky examines in detail the phenomenon of the 'us versus them' dichotomy.

According to the book, there are two kinds of people in the world.

Those who divide people into two types, and those who don't.

And there are more people in the world who fall into the former category.

We all have a tendency to form tribal "us" groups and treat outsiders as inferior "them."

To this Sapolsky asks:

Is the tendency to favor the former after forming an "us/them" dichotomy universal? Is there any hope for overcoming human factionalism and xenophobia?

“People tend to have different but consistent feelings about the four types of extreme cases.

The feeling of warmth/competence (i.e. us) is pride.

I admire coolness/competence.

I feel sorry for the warmth/incompetence.

I have aversion to coldness/incompetence.

(...)

During the Cultural Revolution, China first paraded elites deemed enemies of the people in ridiculous conical hats before sending them to labor camps.

The Nazis already killed people with mental illnesses, which were considered cold/incompetent, without any ceremony.

But the Jews who were considered cold/competent were first made to wear insulting yellow armbands, forced to cut each other's beards, and made to scrub the pavement with toothbrushes in front of a laughing crowd, and then killed.

Idi Amin used his army to steal, beat, and rape tens of thousands of Indo-Pakistani nationals, who were considered cool/competent, before deporting them to Uganda.

“Some of the worst atrocities humans commit are those that try to turn those in the cold/competent category into those in the cold/incompetent category.” _〈Chapter 11.

Among us and them

According to Sapolsky, here's a list of things we should consider to mitigate the negative effects of this us/them mentality:

Emphasize individualization and common characteristics, take perspective, shift to more harmless dichotomies, reduce hierarchical differences, and engage people in the pursuit of common goals on equal terms for all.

And what he emphasizes above all else is context.

Sapolsky says:

“It is not appropriate to ask what a gene does; we can only ask what the gene does in the environment in which it is studied.”

Furthermore, the book illuminates the transition from acts of hate to acts of love, from the impulse to dehumanize others to the ability to rehumanize them, and continues the story through the events of the "coexistence and co-prosperity" ceasefire of World War I and the My Lai massacre.

The story of the My Lai massacre, in particular, offers hopeful evidence that, despite countless obstacles, we can ultimately move forward with the 'best' course of action.

On March 16, 1968, during the Vietnam War, a company of American soldiers, under the orders of Second Lieutenant William Kelly Jr., attacked unarmed civilians in the village of My Lai.

They killed 350 to 500 unarmed civilians, including babies and the elderly, mutilating their bodies and throwing them into wells.

And there was someone who stopped this terrible massacre.

The man in the lead was 25-year-old Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson Jr.

Thompson, who flew to the village of My Lai with the intention of helping infantrymen fight the Viet Cong, saw American soldiers approaching women, children, and elderly men huddled in a bunker in an attack posture.

At that moment, he did something so strong and brave that it was almost dizzying.

It was an action that could change the entire narrative of us/them categorization in an instant.

Hugh Thompson landed his helicopter among the townspeople and soldiers, and turned his machine gun on his fellow Americans.

More than 20 years later, Thompson reflected on his feelings toward those American soldiers: “It was, you know, at that moment, I think they were my enemies.

“Certainly, to the people who were there at that time, they were the enemy,” he explained.

Sapolsky says about this:

“We have seen one individual change the course of history across 20 countries through impulsive action.

I have seen one individual overcome decades of hatred and become a catalyst for reconciliation.

“I’ve seen people completely suppress the reflexes they’ve learned through training in order to do the right thing.”

The reason why the recommendation from bestselling author Charles Duhigg, “‘Action’ is more than hope; it shows us how we can act in ways that bring out more of our best selves and less of our worst selves, both as individuals and as a society,” is so persuasive is because it presents such solid evidence that we can ‘act our best’ ‘despite all that.’

In other words, this book, "Action," is a scientific bridgehead for objectively and rationally understanding the "special cruelty" of our nature and for moving forward vigorously with "rare altruism," and it is a great intellectual journey toward restoring humanity.

A model work of popular science, challenging yet accessible.

― 『Kirkus Review』

A miraculous synthesis of academic disciplines that takes readers on an epic journey.

― The Guardian

A valuable work worthy of being called a new classic in science literature.

It is sure to spark debate for years to come.

―Minneapolis Star Tribune

A journey to understand where our actions come from.

Even Darwin would have been moved if he had read this book.

― The New York Times

Sapolsky travels across the worlds of psychology, primatology, sociology, and neurobiology to present a delightfully accessible and engaging adventure into why we behave the way we do.

This is by far the best book I've read in years.

― The Washington Post

The book covers a wide range of topics, from moral philosophy to social science, genetics to neurons and hormones, but it all points squarely at the question of why humans are so terrible to one another.

― The Vulture

A primatologist, neuroscientist, and science communicator, he writes like a teacher: witty, knowledgeable, and passionate about clear communication.

― 『Nature』

A truly all-encompassing… …detailed, accessible, and fascinating book.

― The Telegraph

Sapolsky tells a realistic story of biology, not a lofty moral drama about choosing between good and evil.

― Booklist

A heroic insight into the duality of our nature: its "special cruelty" and its "rare altruism"!

“Even Darwin would have been thrilled to read this book!” - The New York Times

Robert M., one of the world's leading neuroscientists, whom social psychologist Jonathan Haidt called "a brilliant guide to human nature" and neurologist Oliver Sacks called "the greatest science writer of our time."

Sapolsky's book, "Action," has finally been published in Korea.

This masterpiece, which took more than 10 years to write, has garnered attention and interest from the public and academic circles since its publication, becoming a New York Times bestseller, winning the LA Times Book Award, and being selected as one of the Washington Post's "Best Books of the Year." It is a "dazzling attempt to outline the science of human behavior" and a "clear guide to the complex world of human nature."

The central question that runs through this book is, “Why do humans sometimes treat each other with unspeakable horrors, and at other times with unparalleled generosity?”

To explore the duality of our nature—our "special cruelty" and our "rare altruism"—the author crosses a wide range of academic disciplines, from neurobiology and brain science to genetics, sociobiology, and psychology, providing a comprehensive overview of cutting-edge research.

And based on that understanding, it answers some of the most profound and contradictory questions about human society: tribalism and xenophobia, hierarchy and competition, morality and free will, war and peace.

This is why Michael Shermer, founder of the world-renowned science journal Skeptic, praised this book Behavior as “a magnificent pinnacle of synthesis, on par with Guns, Germs, and Steel and The Better Angels of Our Nature,” and the New York Times commented, “Even Darwin would have been thrilled to read this book.”

“The central argument of this book is that we do not hate violence.

What we hate and fear is the wrong kind of violence, violence in the wrong context.

Because violence in the right context is different.

(...) This ambiguity—that the act of pulling the trigger of a gun can be either a vicious act of aggression or an act of self-sacrificing love—is what makes violence so difficult to understand.

This book will examine the biology of violence, aggression, and competition.

We will examine the actions and impulses behind such phenomena, the actions of individuals, groups, and nations, and when these actions are bad or good.

We will examine the many ways in which humans harm one another.

But at the same time, we will also look at ways in which people behave in the opposite way.

“What can biology tell us about cooperation, alliances, reconciliation, empathy, and altruism?” _From the Preface

Everything You Need to Know About Human Behavior from a "Superb Guide to Human Nature"

“A book that tells the most important story a human being can tell.”

- Edward O.

Wilson, biologist and professor emeritus at Harvard University

"A majestic pinnacle of synthesis, on par with Guns, Germs, and Steel and The Better Angels of Our Nature."

- Michael Shermer, founder of Skeptic

Why on earth do we do 'that'?

Sapolsky examines this question from multiple angles, defying all academic disciplines to faithfully answer it in a way only he can.

He presents a composition that is not only interesting but also follows a compelling internal logic.

First, we look at the factors that influenced a person's reaction at the moment of someone's action, and then we go back in time (from a second ago, to a few hours ago, to a few days ago, to the time when the person was a fertilized egg) and finally we look at the legacy left behind by our species' long evolutionary history.

The first half of the book, comprising chapters 1 through 10 of a total of 17, focuses on transcending the interdisciplinary boundaries of existing research.

'How do neurons and hormones interact?' 'Why are emotions an essential element of decision-making?' 'Why are adolescents more prone to violence than adults?' 'How do genes and culture influence each other?' We examine the influence of the brain, genes, hormones, childhood, cultural environment, evolution, and ecosystems on our aggression, violence, competitiveness, cooperation, altruism, empathy, and sense of belonging.

The scholarly depth and breadth of this book, built on Sapolsky's own research and extensive knowledge of neurobiology, genetics, and behavior, are truly astonishing.

“It tells the most important story that humans can tell,” said biologist Edward O.

This is why I find myself nodding in agreement with Wilson's comments.

Another strength of this book that cannot be overlooked is that it is 'fun'.

Wise, humane, and often downright funny, this book, "Action," by an author renowned for her profound writing and witty humor—so much so that the New York Times once said, "If you mixed Jane Goodall with a comedian, she'd write like Sapolsky." It's a heroic achievement in its own right.

# action

So, 'some' action occurred.

It might be a bad thing.

You pulled the trigger and shot an innocent person.

Maybe it's a good thing.

You pulled the trigger to attract the enemy's attention and save someone else.

Anyway, the important question here is this:

Why did that behavior occur?

# 1 second ago

The book begins with the dimension closest to us in time.

What was going on in that person's head just "one second" before they committed that action? What critical event occurred that second before that led to that prosocial or antisocial behavior? This is a question of neurobiology.

Here we see evidence that the limbic system plays a key role in emotional activity, which drives both the best and worst behaviors; that the prefrontal cortex, the most recently evolved part of the cortex that governs intellectual functions, controls behavioral regulation and constraints; that the amygdala plays a major role in fear and aggression; and that the dopamine system plays a role in reward and motivation.

“In one study, subjects were shown items they could purchase.

At this time, the degree of activation of the precuneus predicted well the likelihood that the subject would pay.

Then I told them the price.

If the price was lower than the subject was willing to pay, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for emotion, was activated.

When it was more expensive, the insular cortex, which is involved in disgust, was activated.

By combining this brain imaging data, they were able to predict whether the subject would buy the item or not.

In this typical mammal, the dopamine system encodes both good and bad surprises in a wide range of ways, and it constantly habituates them to yesterday's news.

But humans have something to add to this.

“The point is that we invent pleasures that are far more intense than any pleasure nature provides.” _〈Chapter 2.

From 1 second ago

# seconds to minutes ago ~ hours to days ago

Now let's look at a point a little further ahead.

What visual, auditory, and olfactory stimuli might have acted on his nervous system to trigger that behavior? And what hormones, hours or days prior, might have influenced his response to those stimuli? Expanding his perspective to this level, Sapolsky draws on not only neurobiology but also the sensory world surrounding us and endocrinology to explain "what" behavior.

This shows that sensory and interoceptive information can influence the brain and trigger behavior in seconds or minutes, and that sights, smells, stomach aches, word choices, and even more subtle cues can influence us unconsciously.

We also learn that testosterone, known as the aggression hormone, does not ‘invent’ aggression, and that oxytocin and vasopressin also reduce anxiety and stress, and promote cooperation and tolerance, but only in certain contexts (these hormones promote prosociality only toward ‘us’, but increase xenophobia when dealing with ‘them’).

“A beautiful study by Karsten Dudrö at the University of Amsterdam showed that oxytocin may not be really warm and pleasant.

First, the male subjects were divided into two teams.

Each subject decided how much of his own money he would contribute to the property shared with his teammates.

As always, oxytocin increased generosity at this time.

Next, the subjects played the prisoner's dilemma game with people from another team.

When the stakes were high and subjects were more motivated, oxytocin made them more likely to preemptively betray their partner.

In short, oxytocin increases prosociality toward people like us (such as teammates), but makes us more willing to be annoying toward others we perceive as a threat.

As Dudreux points out, oxytocin may have evolved to enhance our social capacity to better recognize who is on our side.” _〈Chapter 4.

From a few hours to a few days ago

# A few months ago - adolescence - childhood - fetus, and...

Sapolsky's questions continue.

How did the structural changes his nervous system underwent over the past few months affect his behavior? How did the adversity he experienced as a teenager, a child, and a fetus influence his adult life? What were the social pressures from his peers during his teenage years, the hormonal changes of his adolescence, his childhood home environment, his postnatal brain development, and the amount of maternal hormones supplied through the fetal bloodstream? What were the implications of his genes?

Finally, the author expands his perspective by asking how culture has influenced the groups to which individuals belong, and how ecological factors at work over the past thousands of years have shaped that culture.

And finally, we see the evolutionary factors that have been at work over the past millions of years.

nevertheless,

A journey of knowledge: from 'worst' to 'best', from 'despair' to 'hope'

The second half of the book, chapters 11 through 17, synthesizes the material covered in the first half and examines the areas of human behavior where the material most importantly applies.

First, Sapolsky examines in detail the phenomenon of the 'us versus them' dichotomy.

According to the book, there are two kinds of people in the world.

Those who divide people into two types, and those who don't.

And there are more people in the world who fall into the former category.

We all have a tendency to form tribal "us" groups and treat outsiders as inferior "them."

To this Sapolsky asks:

Is the tendency to favor the former after forming an "us/them" dichotomy universal? Is there any hope for overcoming human factionalism and xenophobia?

“People tend to have different but consistent feelings about the four types of extreme cases.

The feeling of warmth/competence (i.e. us) is pride.

I admire coolness/competence.

I feel sorry for the warmth/incompetence.

I have aversion to coldness/incompetence.

(...)

During the Cultural Revolution, China first paraded elites deemed enemies of the people in ridiculous conical hats before sending them to labor camps.

The Nazis already killed people with mental illnesses, which were considered cold/incompetent, without any ceremony.

But the Jews who were considered cold/competent were first made to wear insulting yellow armbands, forced to cut each other's beards, and made to scrub the pavement with toothbrushes in front of a laughing crowd, and then killed.

Idi Amin used his army to steal, beat, and rape tens of thousands of Indo-Pakistani nationals, who were considered cool/competent, before deporting them to Uganda.

“Some of the worst atrocities humans commit are those that try to turn those in the cold/competent category into those in the cold/incompetent category.” _〈Chapter 11.

Among us and them

According to Sapolsky, here's a list of things we should consider to mitigate the negative effects of this us/them mentality:

Emphasize individualization and common characteristics, take perspective, shift to more harmless dichotomies, reduce hierarchical differences, and engage people in the pursuit of common goals on equal terms for all.

And what he emphasizes above all else is context.

Sapolsky says:

“It is not appropriate to ask what a gene does; we can only ask what the gene does in the environment in which it is studied.”

Furthermore, the book illuminates the transition from acts of hate to acts of love, from the impulse to dehumanize others to the ability to rehumanize them, and continues the story through the events of the "coexistence and co-prosperity" ceasefire of World War I and the My Lai massacre.

The story of the My Lai massacre, in particular, offers hopeful evidence that, despite countless obstacles, we can ultimately move forward with the 'best' course of action.

On March 16, 1968, during the Vietnam War, a company of American soldiers, under the orders of Second Lieutenant William Kelly Jr., attacked unarmed civilians in the village of My Lai.

They killed 350 to 500 unarmed civilians, including babies and the elderly, mutilating their bodies and throwing them into wells.

And there was someone who stopped this terrible massacre.

The man in the lead was 25-year-old Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson Jr.

Thompson, who flew to the village of My Lai with the intention of helping infantrymen fight the Viet Cong, saw American soldiers approaching women, children, and elderly men huddled in a bunker in an attack posture.

At that moment, he did something so strong and brave that it was almost dizzying.

It was an action that could change the entire narrative of us/them categorization in an instant.

Hugh Thompson landed his helicopter among the townspeople and soldiers, and turned his machine gun on his fellow Americans.

More than 20 years later, Thompson reflected on his feelings toward those American soldiers: “It was, you know, at that moment, I think they were my enemies.

“Certainly, to the people who were there at that time, they were the enemy,” he explained.

Sapolsky says about this:

“We have seen one individual change the course of history across 20 countries through impulsive action.

I have seen one individual overcome decades of hatred and become a catalyst for reconciliation.

“I’ve seen people completely suppress the reflexes they’ve learned through training in order to do the right thing.”

The reason why the recommendation from bestselling author Charles Duhigg, “‘Action’ is more than hope; it shows us how we can act in ways that bring out more of our best selves and less of our worst selves, both as individuals and as a society,” is so persuasive is because it presents such solid evidence that we can ‘act our best’ ‘despite all that.’

In other words, this book, "Action," is a scientific bridgehead for objectively and rationally understanding the "special cruelty" of our nature and for moving forward vigorously with "rare altruism," and it is a great intellectual journey toward restoring humanity.

A model work of popular science, challenging yet accessible.

― 『Kirkus Review』

A miraculous synthesis of academic disciplines that takes readers on an epic journey.

― The Guardian

A valuable work worthy of being called a new classic in science literature.

It is sure to spark debate for years to come.

―Minneapolis Star Tribune

A journey to understand where our actions come from.

Even Darwin would have been moved if he had read this book.

― The New York Times

Sapolsky travels across the worlds of psychology, primatology, sociology, and neurobiology to present a delightfully accessible and engaging adventure into why we behave the way we do.

This is by far the best book I've read in years.

― The Washington Post

The book covers a wide range of topics, from moral philosophy to social science, genetics to neurons and hormones, but it all points squarely at the question of why humans are so terrible to one another.

― The Vulture

A primatologist, neuroscientist, and science communicator, he writes like a teacher: witty, knowledgeable, and passionate about clear communication.

― 『Nature』

A truly all-encompassing… …detailed, accessible, and fascinating book.

― The Telegraph

Sapolsky tells a realistic story of biology, not a lofty moral drama about choosing between good and evil.

― Booklist

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: November 22, 2023

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 1,040 pages | 1,598g | 153*225*60mm

- ISBN13: 9788954696357

- ISBN10: 895469635X

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)