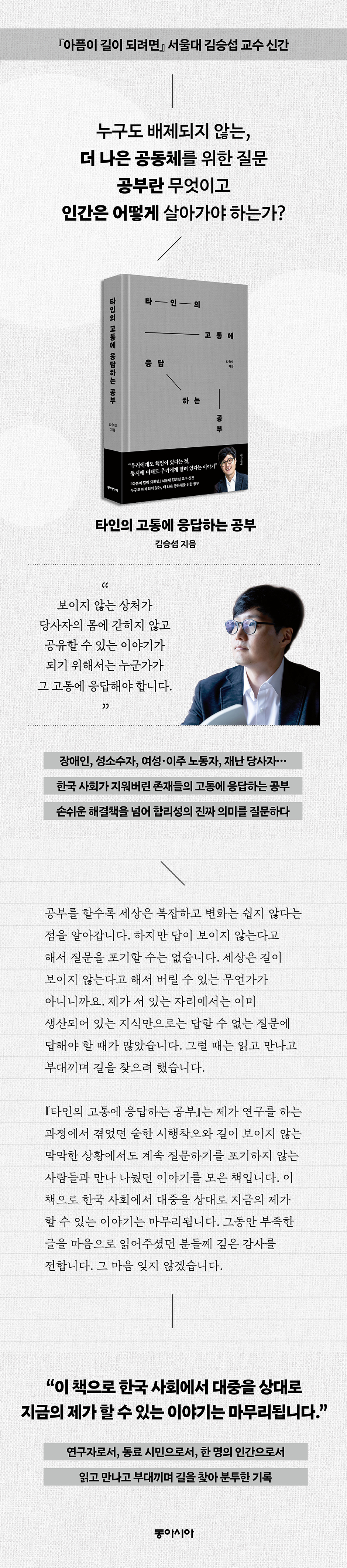

Studying how to respond to the suffering of others

|

Description

Book Introduction

Six years after "If Pain Becomes a Path" A record of Kim Seung-seop's struggles as he read, met, and worked with others. What is study and how should humans live? This is a record of Kim Seung-seop's studies, introducing his research on social responsibility for the health of minorities, and a record of his struggles, confessing the trials and errors he experienced along the way. To respond to the suffering of those erased from Korean society, such as the disabled, sexual minorities, and female workers, with concrete data and precise sentences, he struggles to find a way even in hopeless situations by “reading, meeting, and joining forces.” The book presents a wealth of scholarly material, from 19th-century papers that stigmatized minorities in the name of science to the latest research on the health of sexual minorities in Korea. Kim Seung-seop's conversations with world-renowned scholars such as David Williams and Karen Messing provide an objective look at the situation in Korea, and his photographs add a sense of realism. Kim Seung-seop says: “You can’t give up asking questions just because you can’t see the answer” (p. 6). His questions neither seek only practical solutions nor pursue only political correctness. While emphasizing the need for inclusive restrooms, including for transgender people, the book also points out the stark reality that "for Korean women, public restrooms are unsafe spaces where they must worry about illegal filming and violence" (p. 124). While discussing health policies to reduce new HIV infections, it also considers ways to protect the social dignity of those living with the disease, who must live with it for the rest of their lives. The "study of responding to the suffering of others" he speaks of is the entire process of confronting discrimination, which exists as ubiquitously as air, with accurate data, discussing the suffering of the parties involved, and understanding the complex context of the problem. “From where I stand, there have been many times when I had to answer questions that could not be answered with the knowledge that had already been produced. “At times like that, I tried to find my way by reading, meeting people, and getting along with others.” (Page 6) |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Entering

1.

Discrimination exists like air.

Studying Responding to Others' Suffering 1

Are you a "normal" person? Then you're privileged.

: The logic of vested interests that have discriminated against black people, women, and sexual minorities

The illusion of never discriminating

: The Black Crime Rate in the U.S. and the Controversy Over South Korea's Acceptance of Refugees

About your easy and cruel solution

Discrimination hurts even if you don't actually experience it.

David Williams, a sociologist who began research on racial discrimination and health.

We need your voice out of the closet.

: Psychologist Patrick Corrigan emphasizes the movement of people with mental illness.

Movement, stigma, politics, rationality

2.

Erased existence, unanswered pain

Studying Responding to Others' Suffering 2

The fight for the right to urinate isn't over yet.

: A History of Discrimination and Exclusion Through Restrooms

Who is the "ivory-less elephant" in Korean society?

: Asking about the minimum level of courtesy for humans in the struggle for survival

The fight 'MeToo' where the most hurt people take the lead

: The secondary suffering experienced by the socially disadvantaged who have shown courage

Staring at 'Invisible Pain'

Karen Messing, the scientist who walked into women's workplaces

Who is the basement room evacuation for?

3.

What are the "needle" of Korean society?

Studying Responding to Others' Suffering 3

Awareness of AIDS remains stuck in the 1980s

Needle Exchange Programs and Unscientific Stigma

Change begins with cracks and confusion

: A conversation about HIV infection and disability with activists Kim Do-hyun and Kim Ji-young.

Easy labels don't solve anything.

Don Operario, a health scientist who studies stigma against people living with HIV

A day without fear or censorship

: Celebrating the 20th Seoul Queer Culture Festival

For a society where no one is left behind

Miryu and Jong-geol, activists on hunger strike for the enactment of a comprehensive anti-discrimination law

To move politics that remains silent on discrimination

Economist Lee Badgett refutes politicians' "rational arguments" with data.

Absence of basis or absence of will?

4.

Our lives are more complicated than you imagine.

My essence is something no one can change.

Prosecutor Seo Ji-hyeon on the 'speaking out' of victims in Korean society

The victim is not acting like a victim.

Director Kim Il-ran of the film "Accomplice," which captures the individuality of suffering.

Helen Keller's Light and Shadow

: A conversation with a man who lived through his time, harboring errors and contradictions.

This is my fight

: Can future victims prevail? A conversation with poet Yoo Hee-kyung.

main

1.

Discrimination exists like air.

Studying Responding to Others' Suffering 1

Are you a "normal" person? Then you're privileged.

: The logic of vested interests that have discriminated against black people, women, and sexual minorities

The illusion of never discriminating

: The Black Crime Rate in the U.S. and the Controversy Over South Korea's Acceptance of Refugees

About your easy and cruel solution

Discrimination hurts even if you don't actually experience it.

David Williams, a sociologist who began research on racial discrimination and health.

We need your voice out of the closet.

: Psychologist Patrick Corrigan emphasizes the movement of people with mental illness.

Movement, stigma, politics, rationality

2.

Erased existence, unanswered pain

Studying Responding to Others' Suffering 2

The fight for the right to urinate isn't over yet.

: A History of Discrimination and Exclusion Through Restrooms

Who is the "ivory-less elephant" in Korean society?

: Asking about the minimum level of courtesy for humans in the struggle for survival

The fight 'MeToo' where the most hurt people take the lead

: The secondary suffering experienced by the socially disadvantaged who have shown courage

Staring at 'Invisible Pain'

Karen Messing, the scientist who walked into women's workplaces

Who is the basement room evacuation for?

3.

What are the "needle" of Korean society?

Studying Responding to Others' Suffering 3

Awareness of AIDS remains stuck in the 1980s

Needle Exchange Programs and Unscientific Stigma

Change begins with cracks and confusion

: A conversation about HIV infection and disability with activists Kim Do-hyun and Kim Ji-young.

Easy labels don't solve anything.

Don Operario, a health scientist who studies stigma against people living with HIV

A day without fear or censorship

: Celebrating the 20th Seoul Queer Culture Festival

For a society where no one is left behind

Miryu and Jong-geol, activists on hunger strike for the enactment of a comprehensive anti-discrimination law

To move politics that remains silent on discrimination

Economist Lee Badgett refutes politicians' "rational arguments" with data.

Absence of basis or absence of will?

4.

Our lives are more complicated than you imagine.

My essence is something no one can change.

Prosecutor Seo Ji-hyeon on the 'speaking out' of victims in Korean society

The victim is not acting like a victim.

Director Kim Il-ran of the film "Accomplice," which captures the individuality of suffering.

Helen Keller's Light and Shadow

: A conversation with a man who lived through his time, harboring errors and contradictions.

This is my fight

: Can future victims prevail? A conversation with poet Yoo Hee-kyung.

main

Detailed image

Into the book

Especially those who are hurt by an absurd society often cannot even scream and suffer in silence.

For invisible wounds to become stories that can be shared without being trapped in the body of the person involved, someone must respond to that pain.

--- From "Entering"

In a society where people with disabilities go to work in the morning and return home in the evening, it is impossible for them to not go to the polls, the theater, and the hospital.

--- From "Studying Responding to Others' Suffering 1"

Those who opposed Mr. A's admission ruled out the possibility that he might have been a perpetrator to someone.

So they tried to erase the existence of Ms. A, a trans woman, from the world because they couldn't imagine it.

--- From "Are you a 'normal' person? Then you're privileged."

It takes less than 0.1 second for our brain's neural networks to combine information like skin color or gender at first glance to categorize a person and judge them accordingly.

--- From "The Illusion of Never Discriminating"

I wanted to tell him.

The world has become one where sexual minorities are thinking about death because people like you, as 'experts', are making unscientific claims that are not recognized by any professional society in the world.

What needs to change isn't the sexual orientation of homosexuals, but people like you who don't feel ashamed of violating the minimum ethics that professionals should adhere to.

--- From "Studying Responding to Others' Pain 2"

Just as no one's human rights can be postponed, neither can the rights of women, transgender people, people with disabilities, and countless other diverse minorities to use restrooms.

--- From "The fight for the right to urinate is not over yet"

In a situation where lives that could have been saved if society had observed the "minimum level of decency toward humanity" continue to be unjustly lost, we, as "surviving witnesses," must continue to ask questions.

Where is the 'gorongosa' in Korean society today? Who are the 'ivory-less elephants' surviving in Korean society? Who are the poachers profiting from this absurd struggle for survival?

--- From "Who is the 'ivory-less elephant' in Korean society?"

The lives of sexual minorities who are rejected by their families are pushed to the brink.

The reason why sexual minorities cannot reveal their sexual orientation and gender identity even to their parents, who are the people they live closest to and sometimes the ones they most want to be accepted by, is because they fear rejection and abandonment.

--- From "Studying Responding to Others' Pain 3"

If we could stop all illegal drug use, and thus also stop HIV infection through needle sticks, that would be ideal.

But in a situation where such an ideal policy is not feasible, the New York City Department of Health has found a way that is both feasible and practical.

(…) These efforts have resulted in saving countless lives.

--- From “Awareness of AIDS Stuck in the 1980s”

Kim Do-hyun: I often say that people with disabilities are not discriminated against because they are disabled, but rather become disabled because they are discriminated against.

If we could reach a society where the distinction between people with disabilities and the category itself was no longer necessary, it would probably be a very long way off, but I think that society would be a fundamental step forward from where we are now.

--- From "Change Begins from Cracks and Chaos"

Lee Badgett: We need to move beyond simply saying that homophobes are bad people and analyze the forces at work behind them.

Because now is a 'political moment'.

--- From "To Move Politics Silent on Discrimination"

Seo Ji-hyun: So, this time, when I was doing several media interviews, I said, “Please take a picture of me like Wonder Woman.”

Reporters ask this question a lot.

I heard you're not feeling well, so what's wrong?

But I don't want to talk about that.

I don't want to leave an image that makes me look weak or sad and pitiful.

--- From "No one can change my essence"

I would rather have a conversation with a human being who lived through his time, embracing errors and contradictions, than with a stuffed hero who has "overcome his disability."

--- From "The Light and Shadow of Helen Keller"

No matter how much anger and sadness there is in one's heart, when a scholar writes, he or she must digest and organize the content before writing.

As a scholar, I wanted to give the world the best weapon I could offer.

For invisible wounds to become stories that can be shared without being trapped in the body of the person involved, someone must respond to that pain.

--- From "Entering"

In a society where people with disabilities go to work in the morning and return home in the evening, it is impossible for them to not go to the polls, the theater, and the hospital.

--- From "Studying Responding to Others' Suffering 1"

Those who opposed Mr. A's admission ruled out the possibility that he might have been a perpetrator to someone.

So they tried to erase the existence of Ms. A, a trans woman, from the world because they couldn't imagine it.

--- From "Are you a 'normal' person? Then you're privileged."

It takes less than 0.1 second for our brain's neural networks to combine information like skin color or gender at first glance to categorize a person and judge them accordingly.

--- From "The Illusion of Never Discriminating"

I wanted to tell him.

The world has become one where sexual minorities are thinking about death because people like you, as 'experts', are making unscientific claims that are not recognized by any professional society in the world.

What needs to change isn't the sexual orientation of homosexuals, but people like you who don't feel ashamed of violating the minimum ethics that professionals should adhere to.

--- From "Studying Responding to Others' Pain 2"

Just as no one's human rights can be postponed, neither can the rights of women, transgender people, people with disabilities, and countless other diverse minorities to use restrooms.

--- From "The fight for the right to urinate is not over yet"

In a situation where lives that could have been saved if society had observed the "minimum level of decency toward humanity" continue to be unjustly lost, we, as "surviving witnesses," must continue to ask questions.

Where is the 'gorongosa' in Korean society today? Who are the 'ivory-less elephants' surviving in Korean society? Who are the poachers profiting from this absurd struggle for survival?

--- From "Who is the 'ivory-less elephant' in Korean society?"

The lives of sexual minorities who are rejected by their families are pushed to the brink.

The reason why sexual minorities cannot reveal their sexual orientation and gender identity even to their parents, who are the people they live closest to and sometimes the ones they most want to be accepted by, is because they fear rejection and abandonment.

--- From "Studying Responding to Others' Pain 3"

If we could stop all illegal drug use, and thus also stop HIV infection through needle sticks, that would be ideal.

But in a situation where such an ideal policy is not feasible, the New York City Department of Health has found a way that is both feasible and practical.

(…) These efforts have resulted in saving countless lives.

--- From “Awareness of AIDS Stuck in the 1980s”

Kim Do-hyun: I often say that people with disabilities are not discriminated against because they are disabled, but rather become disabled because they are discriminated against.

If we could reach a society where the distinction between people with disabilities and the category itself was no longer necessary, it would probably be a very long way off, but I think that society would be a fundamental step forward from where we are now.

--- From "Change Begins from Cracks and Chaos"

Lee Badgett: We need to move beyond simply saying that homophobes are bad people and analyze the forces at work behind them.

Because now is a 'political moment'.

--- From "To Move Politics Silent on Discrimination"

Seo Ji-hyun: So, this time, when I was doing several media interviews, I said, “Please take a picture of me like Wonder Woman.”

Reporters ask this question a lot.

I heard you're not feeling well, so what's wrong?

But I don't want to talk about that.

I don't want to leave an image that makes me look weak or sad and pitiful.

--- From "No one can change my essence"

I would rather have a conversation with a human being who lived through his time, embracing errors and contradictions, than with a stuffed hero who has "overcome his disability."

--- From "The Light and Shadow of Helen Keller"

No matter how much anger and sadness there is in one's heart, when a scholar writes, he or she must digest and organize the content before writing.

As a scholar, I wanted to give the world the best weapon I could offer.

--- From "This is my fight"

Publisher's Review

Discrimination hurts even if you don't actually experience it.

A study that responds to the suffering of erased beings

A 1993 paper published by Dr. Knox Todd, an emergency medicine physician, sparked significant controversy.

The research team showed that the factor that most influenced medical staff's prescription of painkillers was the patient's race.

Among Hispanic patients who visited the emergency room with long bone fractures, the rate of not being prescribed painkillers was nearly twice that of white patients.

Even medical professionals who explicitly say they do not discriminate against anyone provide ‘unequal treatment’ based on race, which is due to ‘implicit bias’ inherent in the unconscious.

The problem is that implicit bias hurts minorities even if it doesn't lead to actual discriminatory behavior.

This is because relationships with people who give you negative views increase cortisol, a stress hormone that can cause various diseases.

The situation in Korea is more serious.

Some people cannot go to the hospital even when they are sick.

According to a 2020 National Human Rights Commission survey, one in five transgender people whose gender identity differs from their legal sex at birth said they had avoided using hospitals for fear of being treated unfairly when required to present identification.

People with disabilities who use wheelchairs often give up using public transportation for fear of the harsh stares of drivers and passengers.

Kim Seung-seop points out that Korean society often reveals explicit biases that go beyond implicit biases.

In fact, in the 2018 debate over accepting 484 Yemenis who fled civil war to Jeju Island as refugees, the argument that received a lot of support was an appeal to the explicit prejudice that they "might commit crimes."

Kim Seung-seop confesses that discrimination exists even in the process of studying discrimination, and that not all suffering receives equal attention.

He realizes that the words "transgender research" on the gift certificate he received as compensation for participating in the study could have been outing.

Although I avoided the same mistake in my subsequent research on mobility rights for people with disabilities, the anecdote of a colleague who uses a wheelchair telling me that he had difficulty using a convenience store gift card he received from me made me realize that "discrimination exists like air."

Meanwhile, the researcher's reflection that even he, as a researcher in 2015 when he first conducted research on laid-off workers at Ssangyong Motors, did not consider the wives of laid-off workers as "parties to suffering" led to follow-up research and studies responding to the "invisible pain" of female workers at department stores and duty-free shops.

“I am a researcher, but I do not consider myself a critic, but rather a player on stage.

(…) “The process of looking at the world from the perspective of the socially disadvantaged and producing unproduced knowledge cannot proceed unless someone very intentionally prepares and acts.” (p. 47)

The lives of those affected by hasty solutions have been erased

What is truly a 'reasonable' standard?

In the summer of 2022, a disaster occurred in which three people died in a semi-basement apartment in Sillim-dong, Seoul, due to record-breaking heavy rain.

Two days later, the Seoul Metropolitan Government announced a "safety measure" to ban living in basements and semi-basements.

It was a decision that did not take into account the complex circumstances of the person who had no choice but to live in a semi-basement apartment.

Kim Seung-seop asserts that this hasty solution, reminiscent of the "abolition of the Coast Guard" during the Sewol ferry disaster, cannot solve the problem.

Meanwhile, in 1988, New York City, USA, implemented the so-called "needle exchange program," focusing on the lives of those affected. To reduce new HIV infections, the program provided free, clean needles to drug addicts, defying social stigma.

This policy immediately sparked huge controversy, but ultimately saved countless lives.

Don Operario, a public health researcher who studies the stigma of people living with HIV, says in a conversation with Seungseop Kim that “public health interventions do not make value judgments about an individual’s life” (p. 212).

It's like the needle program that finds a way to save lives immediately before making a value judgment about drug addiction.

However, facing the general premise of health science that 'life is better than death', Seungseop Kim goes one step further and asks this question.

“Is life truly better than death for every individual?” “Must those with incurable diseases continue to struggle under that burden?” (pp. 176-177) This question soon leads to a discussion about the need for a comprehensive anti-discrimination law in Korean society.

“I believe that a world where all minorities can affirm themselves without fear is the foundation of democracy.” (p. 220)

In the book, Seungseop Kim shares his experiences writing expert opinions and testifying in court in lawsuits involving victims of occupational diseases, survivors of sexual violence, and sexual minorities.

It is said that in such cases, lawyers from large law firms on the opposing side often win by providing evidence to support their claims and presenting rational arguments with an elegant face.

“But some people have no basis for their claims other than the hardships of their own lives and the wounds deeply engraved in their bodies.”

He asks, “What should be the ‘rational’ standard for distinguishing between rationality and coercion under such conditions?” (p. 97).

In a Korean society where anti-discrimination laws are often dismissed as something to be dealt with later, citing the "rational" basis of social consensus, the question posed by a researcher who has agonized over scientific rationality more intensely than anyone else resonates deeply.

“Good intentions do not produce good results.

The world is complicated.

Solving social problems begins with accepting their complexity.

Instead of untangling a complex knot, cutting it with a large sword might make the wielder look like a hero.

But that heroic decision often makes things worse.” (p. 161)

Each and every person with their own unique history

The victim is not acting like a victim.

In the book, Seung-seop Kim meets with Prosecutor Ji-hyeon Seo, who sparked the Me Too movement in 2018, and Director Il-ran Kim, whose film "Accomplices," which captures the individual suffering of the victims of the Yongsan tragedy, is also featured.

David Williams, Patrick Corrigan, and Lee Badgett, who share their stories in chapters 1-3, have each experienced racism, mental illness stigma, and homophobia.

What they consistently say is that victims and minorities each have their own unique history and desires, and diverse identities.

Prosecutor Seo Ji-hyeon rejects the typical victim-like behavior demanded by Korean society, saying, “It is the victims who should be happy” (p. 254).

Director Kim Il-ran says that the “image of the victim that we know is only a part” (p. 266), and that we must look at the three-dimensional aspects of the victims.

In that respect, Helen Keller's story is noteworthy.

Helen Keller's life is filled with not only brilliant achievements but also the limitations and contradictions of her time.

However, Seungseop Kim says that there is no reason to belittle Helen Keller's life just because she had limitations and contradictions as well as her achievements. Rather, he says, "I would like to have more conversations with a human being who lived through her time with errors and contradictions, rather than with a stuffed hero who 'overcame her disability'" (p. 285).

That may be why he so freely confessed the sorrows and hardships he felt while researching in this book.

This is also why we must ‘study responding to the suffering of others’ in an age when “judgments about people and events are made in the name of justice by quoting a few words out of context” (p. 8).

“Even in every disaster or calamity, each human being is unique.

Each individual has different needs and concerns within their own unique relationships, history, and circumstances.

But we often consider them as one homogeneous group because we have experienced some common event.” (p. 300)

Between data and emotion

The best weapon you can have as a scholar

Kim Seung-seop says that he wanted the content of his first book, “For Pain to Become a Path,” to be “used as a small weapon that can be held in the hands of those who have nowhere to lean on, rather than as universal knowledge welcomed by everyone” (p. 8).

Regarding his previous work, “The Future Victims Won,” which tells the story of the Cheonan survivors, he said, “As a scholar, I wanted to present to the world the best weapon I could offer” (p. 294).

To this end, Seungseop Kim meticulously refines his language, ensuring that it neither lingers in academic language that is difficult for people to approach nor ends in emotional writing unsupported by data.

To borrow his expression, it is a process of broadening the point where “the warp that cultivates insight into the incident” meets “the weft that throws my body into the incident to sharpen my senses” while reading papers and books (p. 311).

"Studying to Respond to the Pain of Others" is another weapon that Kim Seung-seop has put forth as a "sincere scholar."

In the book, he cautiously but firmly voices his opinion on the most sensitive topics in Korean society, such as the 'controversy over accepting Yemeni refugees,' 'the enactment of a comprehensive anti-discrimination law,' and 'the struggle for the right to mobility for the disabled,' as well as on incidents where public opinion is tilted in one direction.

The rigorous approach to the subject, the intense questions that delve into the root cause of the cause, and the characteristically neat sentences have become even more profound.

Kim Seung-seop, who questioned the social responsibility for disease in “If Pain Becomes a Path” and the academic community’s responsibility for unproduced knowledge in “If Our Body Is the World,” asks himself in this book about his own responsibility as someone who “studies in response to the pain of others.”

Can we really say that this study has nothing to do with us?

“Studying Responses to Others’ Pain” is a collection of stories I shared with people who, despite the countless trials and errors I experienced during my research and the seemingly endless challenges I faced, never gave up asking questions.

“This book concludes the story I can tell the public in Korean society.” (pp. 7-8)

A study that responds to the suffering of erased beings

A 1993 paper published by Dr. Knox Todd, an emergency medicine physician, sparked significant controversy.

The research team showed that the factor that most influenced medical staff's prescription of painkillers was the patient's race.

Among Hispanic patients who visited the emergency room with long bone fractures, the rate of not being prescribed painkillers was nearly twice that of white patients.

Even medical professionals who explicitly say they do not discriminate against anyone provide ‘unequal treatment’ based on race, which is due to ‘implicit bias’ inherent in the unconscious.

The problem is that implicit bias hurts minorities even if it doesn't lead to actual discriminatory behavior.

This is because relationships with people who give you negative views increase cortisol, a stress hormone that can cause various diseases.

The situation in Korea is more serious.

Some people cannot go to the hospital even when they are sick.

According to a 2020 National Human Rights Commission survey, one in five transgender people whose gender identity differs from their legal sex at birth said they had avoided using hospitals for fear of being treated unfairly when required to present identification.

People with disabilities who use wheelchairs often give up using public transportation for fear of the harsh stares of drivers and passengers.

Kim Seung-seop points out that Korean society often reveals explicit biases that go beyond implicit biases.

In fact, in the 2018 debate over accepting 484 Yemenis who fled civil war to Jeju Island as refugees, the argument that received a lot of support was an appeal to the explicit prejudice that they "might commit crimes."

Kim Seung-seop confesses that discrimination exists even in the process of studying discrimination, and that not all suffering receives equal attention.

He realizes that the words "transgender research" on the gift certificate he received as compensation for participating in the study could have been outing.

Although I avoided the same mistake in my subsequent research on mobility rights for people with disabilities, the anecdote of a colleague who uses a wheelchair telling me that he had difficulty using a convenience store gift card he received from me made me realize that "discrimination exists like air."

Meanwhile, the researcher's reflection that even he, as a researcher in 2015 when he first conducted research on laid-off workers at Ssangyong Motors, did not consider the wives of laid-off workers as "parties to suffering" led to follow-up research and studies responding to the "invisible pain" of female workers at department stores and duty-free shops.

“I am a researcher, but I do not consider myself a critic, but rather a player on stage.

(…) “The process of looking at the world from the perspective of the socially disadvantaged and producing unproduced knowledge cannot proceed unless someone very intentionally prepares and acts.” (p. 47)

The lives of those affected by hasty solutions have been erased

What is truly a 'reasonable' standard?

In the summer of 2022, a disaster occurred in which three people died in a semi-basement apartment in Sillim-dong, Seoul, due to record-breaking heavy rain.

Two days later, the Seoul Metropolitan Government announced a "safety measure" to ban living in basements and semi-basements.

It was a decision that did not take into account the complex circumstances of the person who had no choice but to live in a semi-basement apartment.

Kim Seung-seop asserts that this hasty solution, reminiscent of the "abolition of the Coast Guard" during the Sewol ferry disaster, cannot solve the problem.

Meanwhile, in 1988, New York City, USA, implemented the so-called "needle exchange program," focusing on the lives of those affected. To reduce new HIV infections, the program provided free, clean needles to drug addicts, defying social stigma.

This policy immediately sparked huge controversy, but ultimately saved countless lives.

Don Operario, a public health researcher who studies the stigma of people living with HIV, says in a conversation with Seungseop Kim that “public health interventions do not make value judgments about an individual’s life” (p. 212).

It's like the needle program that finds a way to save lives immediately before making a value judgment about drug addiction.

However, facing the general premise of health science that 'life is better than death', Seungseop Kim goes one step further and asks this question.

“Is life truly better than death for every individual?” “Must those with incurable diseases continue to struggle under that burden?” (pp. 176-177) This question soon leads to a discussion about the need for a comprehensive anti-discrimination law in Korean society.

“I believe that a world where all minorities can affirm themselves without fear is the foundation of democracy.” (p. 220)

In the book, Seungseop Kim shares his experiences writing expert opinions and testifying in court in lawsuits involving victims of occupational diseases, survivors of sexual violence, and sexual minorities.

It is said that in such cases, lawyers from large law firms on the opposing side often win by providing evidence to support their claims and presenting rational arguments with an elegant face.

“But some people have no basis for their claims other than the hardships of their own lives and the wounds deeply engraved in their bodies.”

He asks, “What should be the ‘rational’ standard for distinguishing between rationality and coercion under such conditions?” (p. 97).

In a Korean society where anti-discrimination laws are often dismissed as something to be dealt with later, citing the "rational" basis of social consensus, the question posed by a researcher who has agonized over scientific rationality more intensely than anyone else resonates deeply.

“Good intentions do not produce good results.

The world is complicated.

Solving social problems begins with accepting their complexity.

Instead of untangling a complex knot, cutting it with a large sword might make the wielder look like a hero.

But that heroic decision often makes things worse.” (p. 161)

Each and every person with their own unique history

The victim is not acting like a victim.

In the book, Seung-seop Kim meets with Prosecutor Ji-hyeon Seo, who sparked the Me Too movement in 2018, and Director Il-ran Kim, whose film "Accomplices," which captures the individual suffering of the victims of the Yongsan tragedy, is also featured.

David Williams, Patrick Corrigan, and Lee Badgett, who share their stories in chapters 1-3, have each experienced racism, mental illness stigma, and homophobia.

What they consistently say is that victims and minorities each have their own unique history and desires, and diverse identities.

Prosecutor Seo Ji-hyeon rejects the typical victim-like behavior demanded by Korean society, saying, “It is the victims who should be happy” (p. 254).

Director Kim Il-ran says that the “image of the victim that we know is only a part” (p. 266), and that we must look at the three-dimensional aspects of the victims.

In that respect, Helen Keller's story is noteworthy.

Helen Keller's life is filled with not only brilliant achievements but also the limitations and contradictions of her time.

However, Seungseop Kim says that there is no reason to belittle Helen Keller's life just because she had limitations and contradictions as well as her achievements. Rather, he says, "I would like to have more conversations with a human being who lived through her time with errors and contradictions, rather than with a stuffed hero who 'overcame her disability'" (p. 285).

That may be why he so freely confessed the sorrows and hardships he felt while researching in this book.

This is also why we must ‘study responding to the suffering of others’ in an age when “judgments about people and events are made in the name of justice by quoting a few words out of context” (p. 8).

“Even in every disaster or calamity, each human being is unique.

Each individual has different needs and concerns within their own unique relationships, history, and circumstances.

But we often consider them as one homogeneous group because we have experienced some common event.” (p. 300)

Between data and emotion

The best weapon you can have as a scholar

Kim Seung-seop says that he wanted the content of his first book, “For Pain to Become a Path,” to be “used as a small weapon that can be held in the hands of those who have nowhere to lean on, rather than as universal knowledge welcomed by everyone” (p. 8).

Regarding his previous work, “The Future Victims Won,” which tells the story of the Cheonan survivors, he said, “As a scholar, I wanted to present to the world the best weapon I could offer” (p. 294).

To this end, Seungseop Kim meticulously refines his language, ensuring that it neither lingers in academic language that is difficult for people to approach nor ends in emotional writing unsupported by data.

To borrow his expression, it is a process of broadening the point where “the warp that cultivates insight into the incident” meets “the weft that throws my body into the incident to sharpen my senses” while reading papers and books (p. 311).

"Studying to Respond to the Pain of Others" is another weapon that Kim Seung-seop has put forth as a "sincere scholar."

In the book, he cautiously but firmly voices his opinion on the most sensitive topics in Korean society, such as the 'controversy over accepting Yemeni refugees,' 'the enactment of a comprehensive anti-discrimination law,' and 'the struggle for the right to mobility for the disabled,' as well as on incidents where public opinion is tilted in one direction.

The rigorous approach to the subject, the intense questions that delve into the root cause of the cause, and the characteristically neat sentences have become even more profound.

Kim Seung-seop, who questioned the social responsibility for disease in “If Pain Becomes a Path” and the academic community’s responsibility for unproduced knowledge in “If Our Body Is the World,” asks himself in this book about his own responsibility as someone who “studies in response to the pain of others.”

Can we really say that this study has nothing to do with us?

“Studying Responses to Others’ Pain” is a collection of stories I shared with people who, despite the countless trials and errors I experienced during my research and the seemingly endless challenges I faced, never gave up asking questions.

“This book concludes the story I can tell the public in Korean society.” (pp. 7-8)

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: November 22, 2023

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 320 pages | 626g | 140*215*23mm

- ISBN13: 9788962625813

- ISBN10: 8962625814

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)