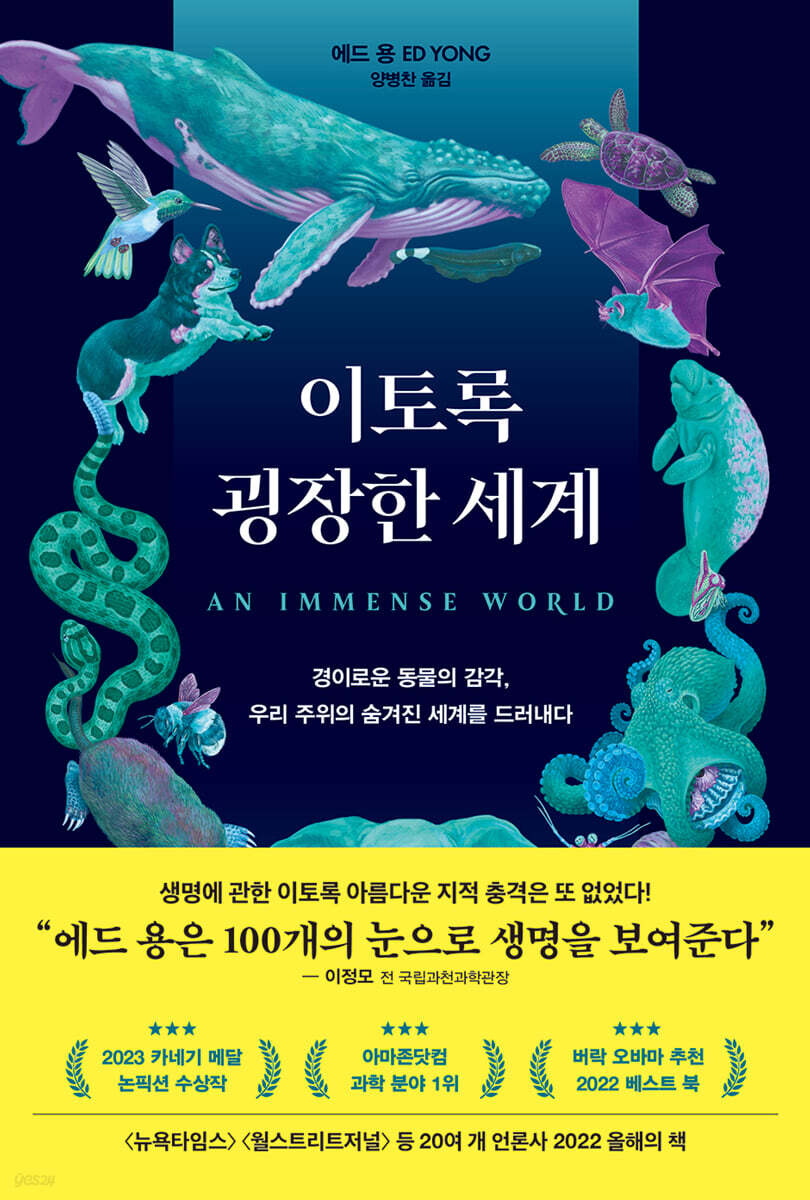

Such a wonderful world

|

Description

Book Introduction

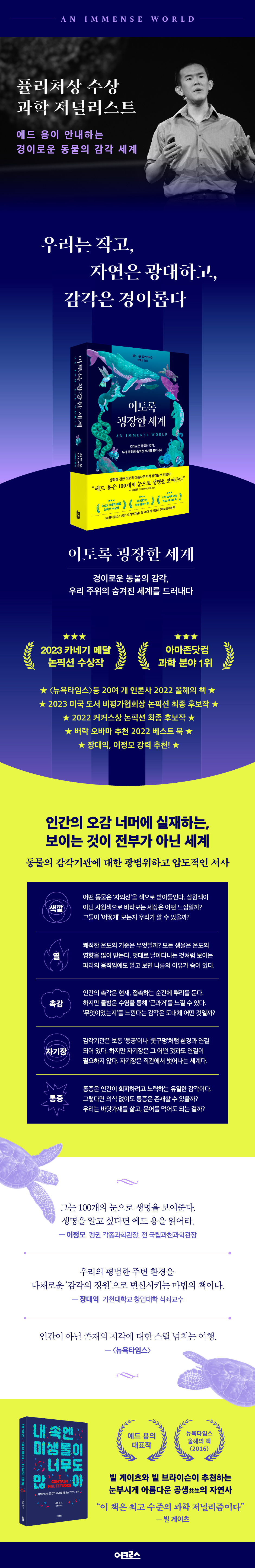

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Ed Yong releases his first new book in six years. There has never been such a beautiful intellectual shock about life! A world that exists beyond the five senses of humans, a world where what you see is not everything. A vast and overwhelming narrative about the animal senses 2023 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Nonfiction Winner 2022 Kirkus Award, 2023 National Book Critics Circle Award for Nonfiction Finalist A New York Times bestseller, #1 on Amazon's science category Barack Obama's Best Books of 2022 Includes 32-page pictorial that vividly captures the wonders of nature. 2022 Book of the Year Lists: The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, TIME, People, The New Yorker, The Washington Post, The Guardian, Slate, Publisher's Weekly, and over 20 others. Ed Yong, the world's most notable science journalist and Pulitzer Prize-winning author, has finally published his book, "This Amazing World." Ed Yong captivated the public and scientific community with his first book, I Contain Multitudes, which explored the world of microbes in 2016 and earned praise from Bill Gates for “top-notch science journalism.” In this new book, which immediately became a New York Times bestseller, he takes us into the wondrous sensory world of animals that transcends the five human senses. The Earth is filled with a variety of sounds and vibrations, smells and tastes, electric and magnetic fields. However, all animals, including humans, perceive only a tiny fraction of the vast world, each surrounded by their own unique "sensory bubble." There are animals in the world who hear sounds in what humans perceive as complete silence, and see colors in what appears to be complete darkness. This book introduces us to numerous animals that defy our intuition, including birds that navigate by smell rather than sight, crickets with hairs sensitive enough to detect the passage of a single photon, and crocodiles with knobs finer than a human fingertip. Imagining how other animals experience the world makes us realize how limited our senses are when it comes to understanding the vastness of our planet. In the preface, the author asks readers to draw an imaginary room. Nine species of animals, including humans, in the room are in the same space, but they perceive each other in completely different ways. The scene unfolds dramatically, as if watching a movie, overwhelming readers from the beginning, and the extensive and captivating narrative of over 600 pages is reminiscent of the zoology book "Cosmos." |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Introduction: A New Way of Understanding the Earth

Chapter 1 Smell and Taste: What Everyone Can Feel Without Exception

Is the human sense of smell terrible? │ Each person's way of smelling the world │ The world of ants and pheromones │ A life governed by smell │ A map drawn with the nose │ Stereo olfaction │ The difference between smell and taste

Chapter 2 Light: Hundreds of Universes Seen by Each Eye

Four Steps to a 'True Eye'│The Relationship Between Sensitivity and Resolution│A Scallop Watching a 'Movie Without Scenes'│Eagles Don't Look Straight Ahead│How to Approach a Fly Without Being Spotted│Their Night Is Like Our Day│The Giant Animal's Even Giant Eyes│Colors That the Night Can't Hide

Chapter 3: Color: A World Unexpressible in Red, Green, and Blue

A 'Lucky Mistake' for Humans│Ultraviolet Light is Just Another Color│The World of Tetrachromats│Colors of a Whole New Dimension│The Optical Luxury of Mantis Shrimp│Polarization Receptors│Which Comes First, the Eyes or the Signal?

Chapter 4 Pain: Is Pain Just Suffering?

Distinguishing Between Nociception and Pain | Do Fish Feel Pain? | The Evolutionary Benefits and Costs of Pain | Pain in Laboratory Animals | Pain Symptoms Vary Among Species

Chapter 5: Heat: Don't worry, it's not cold.

The Secret of the Dancing Fly│A Beetle Rushes Towards Hellfire│“Looking for Blood”│How Do Snakes Detect Heat?

Chapter 6: Touch and Flow: It Doesn't Get Any More Sensitive

The sense of detecting roughness│Tactile, not visual│The usefulness of whiskers│Signals flowing through water and air│Feeling 'what was'│Strange touch sensors│Crocodile protrusions more delicate than human fingertips│Hair that separates life and death│Sensory hairs of spiders, filamentous hairs of crickets

Chapter 7 Surface Vibrations: Stories the Earth Whispers

A Song Created by Tremors│How the Assassin Hunts on the Sand│Creatures That Sense Earthquakes│Elephants That Hear with Their Feet│Spiderwebs, a World Filled with Vibrations

Chapter 8 Sound: In Search of All the Ears of the World

The auditory food chain│'Ears' are optional, not essential│A bat eavesdrops on a frog's serenade│Something humans cannot hear│Ears that change with the seasons│The sea is filled with the voices of whales│Questions no one can answer│Ultrasound, a secret form of communication

Chapter 9: Echoes: The Clapping of a Silent World

Ten Challenges to Echolocation│The Invincible Sonar│The Moth's Retort│The Sense of 'Touching with Sound'│The Dolphin's Clairvoyance│The Man Who Sees the World Through Echoes

Chapter 10 Electric Fields: A Living Battery

Active electrolocation│Perfect communication without information loss│Amplitude of Lorenzini│The complex history of electrosensation│Does electrosensation work on land?

Chapter 11: The Magnetic Field: They Know Which Way to Go

The Biological Compass of Animals│The Amazing Navigational Skills of Turtles│The Veiled Magnetoreceptor│The Counterintuitive World

Chapter 12: Sensory Integration: Looking Through All the Windows Simultaneously

No animal relies solely on one sense│Distinguishing the self from others│The world of the arm and the world of the head│Humans living in illusion and delusion

Chapter 13: The Crisis of the Sense Landscape: Reclaiming Silence and Preserving Darkness

'Light' Pollutes the World│Birds Must Sing Louder│Flattened Sensory Landscape│Removing 'Human-Added Stimuli'│Wonder Is Nearby

Acknowledgements

Americas

References

Photo source

Chapter 1 Smell and Taste: What Everyone Can Feel Without Exception

Is the human sense of smell terrible? │ Each person's way of smelling the world │ The world of ants and pheromones │ A life governed by smell │ A map drawn with the nose │ Stereo olfaction │ The difference between smell and taste

Chapter 2 Light: Hundreds of Universes Seen by Each Eye

Four Steps to a 'True Eye'│The Relationship Between Sensitivity and Resolution│A Scallop Watching a 'Movie Without Scenes'│Eagles Don't Look Straight Ahead│How to Approach a Fly Without Being Spotted│Their Night Is Like Our Day│The Giant Animal's Even Giant Eyes│Colors That the Night Can't Hide

Chapter 3: Color: A World Unexpressible in Red, Green, and Blue

A 'Lucky Mistake' for Humans│Ultraviolet Light is Just Another Color│The World of Tetrachromats│Colors of a Whole New Dimension│The Optical Luxury of Mantis Shrimp│Polarization Receptors│Which Comes First, the Eyes or the Signal?

Chapter 4 Pain: Is Pain Just Suffering?

Distinguishing Between Nociception and Pain | Do Fish Feel Pain? | The Evolutionary Benefits and Costs of Pain | Pain in Laboratory Animals | Pain Symptoms Vary Among Species

Chapter 5: Heat: Don't worry, it's not cold.

The Secret of the Dancing Fly│A Beetle Rushes Towards Hellfire│“Looking for Blood”│How Do Snakes Detect Heat?

Chapter 6: Touch and Flow: It Doesn't Get Any More Sensitive

The sense of detecting roughness│Tactile, not visual│The usefulness of whiskers│Signals flowing through water and air│Feeling 'what was'│Strange touch sensors│Crocodile protrusions more delicate than human fingertips│Hair that separates life and death│Sensory hairs of spiders, filamentous hairs of crickets

Chapter 7 Surface Vibrations: Stories the Earth Whispers

A Song Created by Tremors│How the Assassin Hunts on the Sand│Creatures That Sense Earthquakes│Elephants That Hear with Their Feet│Spiderwebs, a World Filled with Vibrations

Chapter 8 Sound: In Search of All the Ears of the World

The auditory food chain│'Ears' are optional, not essential│A bat eavesdrops on a frog's serenade│Something humans cannot hear│Ears that change with the seasons│The sea is filled with the voices of whales│Questions no one can answer│Ultrasound, a secret form of communication

Chapter 9: Echoes: The Clapping of a Silent World

Ten Challenges to Echolocation│The Invincible Sonar│The Moth's Retort│The Sense of 'Touching with Sound'│The Dolphin's Clairvoyance│The Man Who Sees the World Through Echoes

Chapter 10 Electric Fields: A Living Battery

Active electrolocation│Perfect communication without information loss│Amplitude of Lorenzini│The complex history of electrosensation│Does electrosensation work on land?

Chapter 11: The Magnetic Field: They Know Which Way to Go

The Biological Compass of Animals│The Amazing Navigational Skills of Turtles│The Veiled Magnetoreceptor│The Counterintuitive World

Chapter 12: Sensory Integration: Looking Through All the Windows Simultaneously

No animal relies solely on one sense│Distinguishing the self from others│The world of the arm and the world of the head│Humans living in illusion and delusion

Chapter 13: The Crisis of the Sense Landscape: Reclaiming Silence and Preserving Darkness

'Light' Pollutes the World│Birds Must Sing Louder│Flattened Sensory Landscape│Removing 'Human-Added Stimuli'│Wonder Is Nearby

Acknowledgements

Americas

References

Photo source

Detailed image

Into the book

Unlike light, which always travels in a straight line, smells diffuse, permeate, overflow, and swirl.

“Every time I observe Finn sniffing around in a new space, I try to ignore the clear boundaries my vision provides.

Instead, I imagine a 'dimly lit environment' with no distinct boundaries,” says Horowitz.

“There is a focal area, but you could say all areas permeate each other.” Smells move through darkness, around corners, and even under other adverse conditions (such as conditions that obstruct vision).

Horowitz can't see inside the bag hanging on the back of my chair, but Finn can sniff out the molecules drifting from the sandwich inside.

Unlike light, smells can linger in one place for a long time and reveal history.

---From "Pages 41-42, Chapter 1: Smell and Taste: What Everyone Can Feel Without Exception"

Their high-speed hunting is guided by their high-speed vision.

It may sound strange to say that animals have different visual speeds.

Because light is the fastest thing in the universe, and vision seems instantaneous.

But the eyes do not operate at the speed of light.

This is because it takes time for the photoreceptors to react to photons entering the eye and for the electrical signals generated by the photoreceptors to be transmitted to the brain.

In the case of killer flies, evolution has pushed these steps to their limits.

When Gonzalez-Bellido showed them an image, it took only 6 to 9 milliseconds for the photoreceptors to send an electrical signal, for that signal to reach the brain, and for the brain to send a command to the muscles.

In contrast, it takes human photoreceptors 30 to 60 milliseconds to perform the first step of this process.

If you were to view an image simultaneously with a killer fly, the insect would be in the air long before the signal left your retina.

---From "Pages 119-120, Chapter 2, Light: Hundreds of Universes Seen by Each Eye"

If the same gap existed between trichromats and tetrachromats, we would only be able to see about 1 percent of the hundreds of millions of colors that birds can distinguish.

Human trichromatic color vision can be thought of as a triangle, with the three corners representing red, green, and blue cone cells, respectively.

All the colors we can see are mixtures of these three colors, and can be represented as points within a triangular space.

In contrast, the tetrachromatic color vision of birds can be thought of as a pyramid (triangular pyramid), with the four corners representing four cone cells.

Here, our entire color space is just one side of the pyramid, the vast interior of which represents colors that are inaccessible to most humans.

---From "Page 154, Chapter 3: Color: A World That Cannot Be Expressed in Red, Green, and Blue"

People often think that 'the entire animal kingdom feels pain equally,' but that's not true.

Like color, it is inherently subjective and incredibly variable.

Just as light waves are not universally red or blue, and smells are not universally fragrant or pungent, even the chemicals in scorpion venom, which evolved specifically to inflict pain, are not universally painful.

Pain is crucial to animals' survival, as it alerts them to injury and danger.

And while all animals have things to be wary of, what to 'avoid' and what to 'tolerate' varies from species to species.

This is why it is notoriously difficult to tell what an animal finds painful, whether it experiences pain, or even whether it can feel pain.

---From "Page 189, Chapter 4 Pain: Is Pain Just Suffering?"

But when we see extreme creatures, from emperor penguins braving the Antarctic cold to camels trotting across scorching sand, it's easy to assume they're suffering their entire lives.

We admire not only their physiological resilience but also their psychological fortitude.

We project our feelings onto theirs, assuming that if we are uncomfortable, they will be uncomfortable too.

But their senses are tuned to the temperature in which they live.

Camels won't suffer from the blazing sun, and penguins won't mind hunkering down in an Antarctic storm.

No matter how much the storm rages, they never shiver from the cold.

---From "Page 219, Chapter 5, Section 10: Don't worry, it's not cold"

Satisfied, we return to his car.

I suddenly think of the chorus that might be vibrating among all the plants we pass.

At the same time, think about the vibrations we generate with each step we take—surface waves of seismic vibration (a general term for vibrations that occur on the surface of the earth—translator's note) that ripple out from each footstep.

Even though we hear the rustle of branches and the crunch of mud under our feet, we do not detect the tremors of our own footsteps.

But other creatures detect it.

---From "Page 301, Chapter 7, Surface Vibration: Stories the Earth Whispers"

The first lesson we can learn from insect ears is this:

'Hearing is useful, but unlike touch or pain, it is not universal.' In any case, the first insects were deaf.

They had to evolve ears, and they did so on at least nineteen independent occasions over 480 million years of history, and in almost every body part imaginable.

Thus, ears exist in the knees of crickets and cicadas, the abdomens of grasshoppers and cicadas, and the mouths of cicadas.

Mosquitoes hear with their antennae.

Monarch butterfly caterpillars hear with a pair of hairs in their middle part.

The bladder grasshopper has six pairs of ears lining its abdomen, while the mantis has one large ear in the center of its chest.

Insect ears are very diverse, as most evolved from chordotonal organs—motion-sensitive structures found throughout the insect's body.

---From "Pages 328-329, Chapter 8: Sound: In Search of All the Ears of the World"

Instead of stepping into the world of other animals and understanding it, we force them to live in our world by tormenting them with artificial stimuli.

We filled the night with light, the silence with noise, the soil and water with strange molecules.

We distracted animals from what they were actually supposed to sense, drowned out the cues they relied on, and lured them into sensory traps like moths to a flame.

“Every time I observe Finn sniffing around in a new space, I try to ignore the clear boundaries my vision provides.

Instead, I imagine a 'dimly lit environment' with no distinct boundaries,” says Horowitz.

“There is a focal area, but you could say all areas permeate each other.” Smells move through darkness, around corners, and even under other adverse conditions (such as conditions that obstruct vision).

Horowitz can't see inside the bag hanging on the back of my chair, but Finn can sniff out the molecules drifting from the sandwich inside.

Unlike light, smells can linger in one place for a long time and reveal history.

---From "Pages 41-42, Chapter 1: Smell and Taste: What Everyone Can Feel Without Exception"

Their high-speed hunting is guided by their high-speed vision.

It may sound strange to say that animals have different visual speeds.

Because light is the fastest thing in the universe, and vision seems instantaneous.

But the eyes do not operate at the speed of light.

This is because it takes time for the photoreceptors to react to photons entering the eye and for the electrical signals generated by the photoreceptors to be transmitted to the brain.

In the case of killer flies, evolution has pushed these steps to their limits.

When Gonzalez-Bellido showed them an image, it took only 6 to 9 milliseconds for the photoreceptors to send an electrical signal, for that signal to reach the brain, and for the brain to send a command to the muscles.

In contrast, it takes human photoreceptors 30 to 60 milliseconds to perform the first step of this process.

If you were to view an image simultaneously with a killer fly, the insect would be in the air long before the signal left your retina.

---From "Pages 119-120, Chapter 2, Light: Hundreds of Universes Seen by Each Eye"

If the same gap existed between trichromats and tetrachromats, we would only be able to see about 1 percent of the hundreds of millions of colors that birds can distinguish.

Human trichromatic color vision can be thought of as a triangle, with the three corners representing red, green, and blue cone cells, respectively.

All the colors we can see are mixtures of these three colors, and can be represented as points within a triangular space.

In contrast, the tetrachromatic color vision of birds can be thought of as a pyramid (triangular pyramid), with the four corners representing four cone cells.

Here, our entire color space is just one side of the pyramid, the vast interior of which represents colors that are inaccessible to most humans.

---From "Page 154, Chapter 3: Color: A World That Cannot Be Expressed in Red, Green, and Blue"

People often think that 'the entire animal kingdom feels pain equally,' but that's not true.

Like color, it is inherently subjective and incredibly variable.

Just as light waves are not universally red or blue, and smells are not universally fragrant or pungent, even the chemicals in scorpion venom, which evolved specifically to inflict pain, are not universally painful.

Pain is crucial to animals' survival, as it alerts them to injury and danger.

And while all animals have things to be wary of, what to 'avoid' and what to 'tolerate' varies from species to species.

This is why it is notoriously difficult to tell what an animal finds painful, whether it experiences pain, or even whether it can feel pain.

---From "Page 189, Chapter 4 Pain: Is Pain Just Suffering?"

But when we see extreme creatures, from emperor penguins braving the Antarctic cold to camels trotting across scorching sand, it's easy to assume they're suffering their entire lives.

We admire not only their physiological resilience but also their psychological fortitude.

We project our feelings onto theirs, assuming that if we are uncomfortable, they will be uncomfortable too.

But their senses are tuned to the temperature in which they live.

Camels won't suffer from the blazing sun, and penguins won't mind hunkering down in an Antarctic storm.

No matter how much the storm rages, they never shiver from the cold.

---From "Page 219, Chapter 5, Section 10: Don't worry, it's not cold"

Satisfied, we return to his car.

I suddenly think of the chorus that might be vibrating among all the plants we pass.

At the same time, think about the vibrations we generate with each step we take—surface waves of seismic vibration (a general term for vibrations that occur on the surface of the earth—translator's note) that ripple out from each footstep.

Even though we hear the rustle of branches and the crunch of mud under our feet, we do not detect the tremors of our own footsteps.

But other creatures detect it.

---From "Page 301, Chapter 7, Surface Vibration: Stories the Earth Whispers"

The first lesson we can learn from insect ears is this:

'Hearing is useful, but unlike touch or pain, it is not universal.' In any case, the first insects were deaf.

They had to evolve ears, and they did so on at least nineteen independent occasions over 480 million years of history, and in almost every body part imaginable.

Thus, ears exist in the knees of crickets and cicadas, the abdomens of grasshoppers and cicadas, and the mouths of cicadas.

Mosquitoes hear with their antennae.

Monarch butterfly caterpillars hear with a pair of hairs in their middle part.

The bladder grasshopper has six pairs of ears lining its abdomen, while the mantis has one large ear in the center of its chest.

Insect ears are very diverse, as most evolved from chordotonal organs—motion-sensitive structures found throughout the insect's body.

---From "Pages 328-329, Chapter 8: Sound: In Search of All the Ears of the World"

Instead of stepping into the world of other animals and understanding it, we force them to live in our world by tormenting them with artificial stimuli.

We filled the night with light, the silence with noise, the soil and water with strange molecules.

We distracted animals from what they were actually supposed to sense, drowned out the cues they relied on, and lured them into sensory traps like moths to a flame.

---From "Page 507, Chapter 13, The Crisis of the Sense Landscape: Regaining Silence and Preserving Darkness"

Publisher's Review

Why can mammals other than humans hear 'ultrasound'?

The amazing parallel universes around us where other animals live

Scallops, which have 200 eyes, despite their overwhelming number, do not perceive 'scenes' like we do, but only detect 'movements'.

This is like a surveillance system that has 200 CCTV cameras in different locations, but cannot see the thief's face, yet recognizes the movements of a person who may or may not be a thief.

Unlike other spiders that perceive the world through vibration and touch, jumping spiders actively use their sense of sight.

Jumping spiders have eight eyes, each with a different task: the central eye recognizes patterns and shapes, while the auxiliary eyes track movement, processing a tremendous amount of information.

Chameleons have the ability to look forward and backward simultaneously, or to track two targets moving in opposite directions.

In contrast, humans have only two eyes, located in the center of their heads, a trait that is not at all standard in nature.

There are as many different types of eyes in the world as there are creatures with eyes.

The author makes it clear that this book is not about animals with exceptional sensory organs, but about the diversity of animals.

Rather than trying to imitate animal senses for human benefit or ranking them by admiring their excellence, it is worthwhile to look at animals as they are.

Ed Yong uses the zoologist Jakob von Uexküll's definition of "umwelten" (environmental world) as a key concept in this book, emphasizing that all organisms perceive only a very small part of the world accessible to their senses.

That's why sensations that seem natural to other animals can feel supernatural to humans.

In fact, most mammals can hear well into the ultrasonic range.

The reason we call frequencies that are common to other animals 'ultrasound' is because humans are not as aware of their own limitations.

Rather than categorizing them by the five senses, which is the traditional classification method, this book organizes each chapter by the stimuli that life on Earth can sense (smell, taste, color, heat, sound, surface vibration, electric field, etc.) and the corresponding sense.

Among them are amazing animals that use senses that humans don't have, such as bees that distinguish colors on a whole new level with 'tetrachromatic color vision', elephants that communicate over long distances using 'ground vibrations', and turtles that navigate the Atlantic Ocean for five to ten years using 'magnetic fields'.

In the same physical space called Earth, each living being experiences something completely different, as if they were living in a parallel universe.

We will expand our world by exploring the Earth's environment through the eyes, ears, noses, and skin of animals.

“Is an otter that just floats still on the surface of the water lazy?”

Hidden stories that will make you rethink the movements of every living thing you've ever seen.

The image of a sea otter that we are familiar with is mostly of it lying flat on the surface of the water with both hands on its belly.

Scenes like this lead to the stereotype that they are lazy and apathetic.

But this is a largely human-centric misconception.

Sea otters must eat food equivalent to a quarter of their body weight every day to maintain their body temperature, and they search for food with their busy feet all day and night.

As the weather gets warmer, the number of flies flying around like crazy becomes extreme.

Why do flies fly without stopping? Their antennae can detect even a 0.1 degree temperature difference.

When they sense a temperature difference, they change direction at incredible speed and head towards a slightly more comfortable place.

The author confesses that he has rethought all the movements of flies he has ever observed since he discovered that their paths, which had always seemed random and chaotic, actually had a sense of purpose.

In this way, we are so accustomed to a certain way of looking at the world.

Moreover, humans are very visual animals, so it is very difficult to avoid visual metaphors when explaining other senses.

Even when explaining senses that humans do not have, such as the ability to detect electric fields, scientists invoke “images” and “shadows.”

The scientists featured in this book caution against judging animal lives by our senses rather than theirs, saying that studying animal senses is difficult and requires humility.

But as I gradually come to understand the animal world, I exclaim in admiration:

"We don't need to look for aliens from other planets.

"Right next to you are animals who interpret the world completely differently!" (Elizabeth Jacob, animal vision researcher) Ed Yong vividly and humorously captures stories from the front lines of biology and the minds of researchers who strive to experience the world through the eyes of animals.

Human-induced stimuli are more lethal than plastic waste.

What we must do to regain tranquility and preserve darkness

The new sensory world we will encounter through this book is a world we must imagine, savor, and protect at the same time.

The author warns that "human-induced stimuli," such as persistent light and noise, are polluting the natural world.

People worry about ocean pollution caused by plastic waste, but they are completely unaware of the severity of ocean noise.

The light and sound that humans have thoughtlessly filled in is a serious problem that is driving out the inhabitants who have lived there for millions of years and making their communication powerless.

At the same time, plastic waste takes hundreds of years to decompose, light pollution stops as soon as the lights are turned off, and noise pollution can be solved by reducing the sound of engines and propellers.

While humans are the main culprits in making life harder for other animals than ever before, they are also the only creatures capable of wondering about and understanding how other animals perceive the world.

Ed Yong says that “every time a species disappears from Earth, we lose a way of understanding the world.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, when he wrote this book, he witnessed successful attempts to restore "quietness" and preserve "darkness," and he urges us that there is still a chance.

After examining the vast sensory world of animals, this book ultimately concludes that preserving the richness of our "sensory landscape" is a crucial and urgent task for us and our fellow inhabitants of the Earth, and the first step toward that goal is to understand the environmental worlds of other animals.

The amazing parallel universes around us where other animals live

Scallops, which have 200 eyes, despite their overwhelming number, do not perceive 'scenes' like we do, but only detect 'movements'.

This is like a surveillance system that has 200 CCTV cameras in different locations, but cannot see the thief's face, yet recognizes the movements of a person who may or may not be a thief.

Unlike other spiders that perceive the world through vibration and touch, jumping spiders actively use their sense of sight.

Jumping spiders have eight eyes, each with a different task: the central eye recognizes patterns and shapes, while the auxiliary eyes track movement, processing a tremendous amount of information.

Chameleons have the ability to look forward and backward simultaneously, or to track two targets moving in opposite directions.

In contrast, humans have only two eyes, located in the center of their heads, a trait that is not at all standard in nature.

There are as many different types of eyes in the world as there are creatures with eyes.

The author makes it clear that this book is not about animals with exceptional sensory organs, but about the diversity of animals.

Rather than trying to imitate animal senses for human benefit or ranking them by admiring their excellence, it is worthwhile to look at animals as they are.

Ed Yong uses the zoologist Jakob von Uexküll's definition of "umwelten" (environmental world) as a key concept in this book, emphasizing that all organisms perceive only a very small part of the world accessible to their senses.

That's why sensations that seem natural to other animals can feel supernatural to humans.

In fact, most mammals can hear well into the ultrasonic range.

The reason we call frequencies that are common to other animals 'ultrasound' is because humans are not as aware of their own limitations.

Rather than categorizing them by the five senses, which is the traditional classification method, this book organizes each chapter by the stimuli that life on Earth can sense (smell, taste, color, heat, sound, surface vibration, electric field, etc.) and the corresponding sense.

Among them are amazing animals that use senses that humans don't have, such as bees that distinguish colors on a whole new level with 'tetrachromatic color vision', elephants that communicate over long distances using 'ground vibrations', and turtles that navigate the Atlantic Ocean for five to ten years using 'magnetic fields'.

In the same physical space called Earth, each living being experiences something completely different, as if they were living in a parallel universe.

We will expand our world by exploring the Earth's environment through the eyes, ears, noses, and skin of animals.

“Is an otter that just floats still on the surface of the water lazy?”

Hidden stories that will make you rethink the movements of every living thing you've ever seen.

The image of a sea otter that we are familiar with is mostly of it lying flat on the surface of the water with both hands on its belly.

Scenes like this lead to the stereotype that they are lazy and apathetic.

But this is a largely human-centric misconception.

Sea otters must eat food equivalent to a quarter of their body weight every day to maintain their body temperature, and they search for food with their busy feet all day and night.

As the weather gets warmer, the number of flies flying around like crazy becomes extreme.

Why do flies fly without stopping? Their antennae can detect even a 0.1 degree temperature difference.

When they sense a temperature difference, they change direction at incredible speed and head towards a slightly more comfortable place.

The author confesses that he has rethought all the movements of flies he has ever observed since he discovered that their paths, which had always seemed random and chaotic, actually had a sense of purpose.

In this way, we are so accustomed to a certain way of looking at the world.

Moreover, humans are very visual animals, so it is very difficult to avoid visual metaphors when explaining other senses.

Even when explaining senses that humans do not have, such as the ability to detect electric fields, scientists invoke “images” and “shadows.”

The scientists featured in this book caution against judging animal lives by our senses rather than theirs, saying that studying animal senses is difficult and requires humility.

But as I gradually come to understand the animal world, I exclaim in admiration:

"We don't need to look for aliens from other planets.

"Right next to you are animals who interpret the world completely differently!" (Elizabeth Jacob, animal vision researcher) Ed Yong vividly and humorously captures stories from the front lines of biology and the minds of researchers who strive to experience the world through the eyes of animals.

Human-induced stimuli are more lethal than plastic waste.

What we must do to regain tranquility and preserve darkness

The new sensory world we will encounter through this book is a world we must imagine, savor, and protect at the same time.

The author warns that "human-induced stimuli," such as persistent light and noise, are polluting the natural world.

People worry about ocean pollution caused by plastic waste, but they are completely unaware of the severity of ocean noise.

The light and sound that humans have thoughtlessly filled in is a serious problem that is driving out the inhabitants who have lived there for millions of years and making their communication powerless.

At the same time, plastic waste takes hundreds of years to decompose, light pollution stops as soon as the lights are turned off, and noise pollution can be solved by reducing the sound of engines and propellers.

While humans are the main culprits in making life harder for other animals than ever before, they are also the only creatures capable of wondering about and understanding how other animals perceive the world.

Ed Yong says that “every time a species disappears from Earth, we lose a way of understanding the world.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, when he wrote this book, he witnessed successful attempts to restore "quietness" and preserve "darkness," and he urges us that there is still a chance.

After examining the vast sensory world of animals, this book ultimately concludes that preserving the richness of our "sensory landscape" is a crucial and urgent task for us and our fellow inhabitants of the Earth, and the first step toward that goal is to understand the environmental worlds of other animals.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: April 11, 2023

- Page count, weight, size: 624 pages | 978g | 152*225*35mm

- ISBN13: 9791167740946

- ISBN10: 1167740947

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)