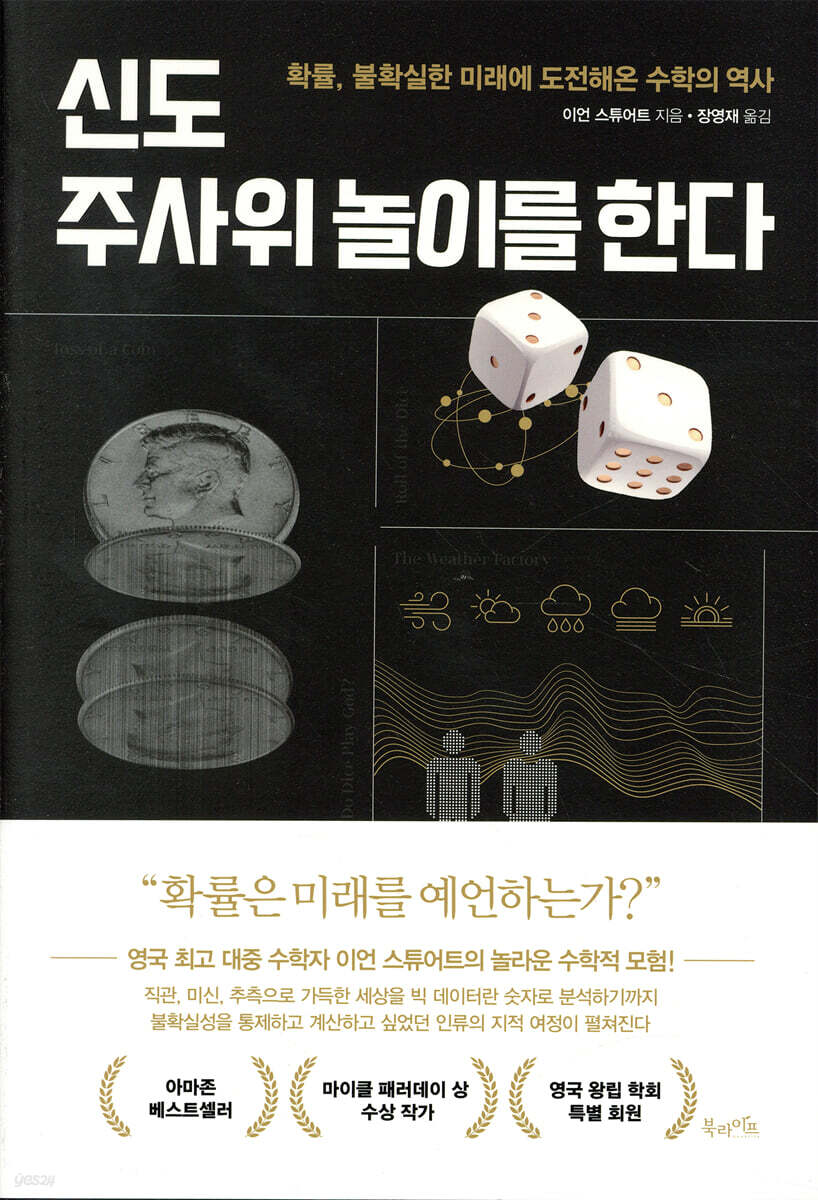

Shinto plays dice

|

Description

Book Introduction

- A word from MD

-

Mathematics that connects the uncertain present and futureIan Stewart's new work.

We examine human history based on 'probability', a mathematical tool invented to prepare for unpredictable situations.

From shamanistic superstitions and gambling to weather forecasting and medical research, this book delves into mathematical efforts to control the uncertain future and the probabilistic errors found in them.

August 18, 2020. Natural Science PD Kim Yu-ri

“Will you leave the future to fate or decide it through your actions?”

From a world filled with intuition, superstition, and speculation to analyzing it with numbers called big data.

The intellectual journey of humanity to control and calculate uncertainty unfolds!

Despite the advancements in medical expertise, why were we unable to foresee the spread of infectious diseases and the prolonged nature of pandemics? Why do weather forecasts from 52 billion won supercomputers consistently receive criticism for being historically inaccurate? Can't we prevent stock market declines and losses in advance? Why, despite the emergence of powerful forecasting tools based on big data and artificial intelligence, can't we even predict the near future with perfect accuracy?

We'd love to know in advance which party will win an election, whether a prime suspect actually committed a crime, or when and how big an earthquake will strike, but whenever we try to predict the outcome of such events, our intuition is usually wrong.

Because the world is full of uncertainty and human predictability is poor.

So, is perfect control over uncertainty forever impossible? When did humanity begin its efforts to predict and control the future? How did humanity calculate uncertainty and foresee the future before technological advancements? Will hyper-predictability become possible in the Fifth Industrial Revolution?

Here's a book that will answer this question.

"God Plays Dice" is a science textbook that shows how humanity's efforts to transform an uncertain world into a certain one, encompassing everyday life, social phenomena, and even natural disasters, have led to the development of mathematics and the creation of the tool of probability over 5,000 years of history.

From a world filled with intuition, superstition, and speculation to analyzing it with numbers called big data.

The intellectual journey of humanity to control and calculate uncertainty unfolds!

Despite the advancements in medical expertise, why were we unable to foresee the spread of infectious diseases and the prolonged nature of pandemics? Why do weather forecasts from 52 billion won supercomputers consistently receive criticism for being historically inaccurate? Can't we prevent stock market declines and losses in advance? Why, despite the emergence of powerful forecasting tools based on big data and artificial intelligence, can't we even predict the near future with perfect accuracy?

We'd love to know in advance which party will win an election, whether a prime suspect actually committed a crime, or when and how big an earthquake will strike, but whenever we try to predict the outcome of such events, our intuition is usually wrong.

Because the world is full of uncertainty and human predictability is poor.

So, is perfect control over uncertainty forever impossible? When did humanity begin its efforts to predict and control the future? How did humanity calculate uncertainty and foresee the future before technological advancements? Will hyper-predictability become possible in the Fifth Industrial Revolution?

Here's a book that will answer this question.

"God Plays Dice" is a science textbook that shows how humanity's efforts to transform an uncertain world into a certain one, encompassing everyday life, social phenomena, and even natural disasters, have led to the development of mathematics and the creation of the tool of probability over 5,000 years of history.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Chapter 1.

Six Ages of Uncertainty

Why and How We Predict the Future | The Second Age of Uncertainty: Bringing Scientific Advancement | Discoveries in Probability, Statistics, and Fundamental Physics | The Fifth Age of Uncertainty and Chaos Theory | The Sixth Age of Uncertainty and Predicting the Future

Chapter 2.

Reading Animal Guts

Humanity's Desire to Predict the Future | How Human Beliefs Become Solid | From Palmistry to Skull Reading and Lottery

Chapter 3.

Rolling the dice

The Birth of Probability Theory and Dice | Mathematicians Who Were Interested in Gambling

Chapter 4.

coin toss

Limiting the Size of Uncertainty | Random Variables and Probability Distributions

Chapter 5.

Too much information

Too much data creates errors | The birth of least squares and the central limit theorem | Write down what probability does.

Chapter 6.

Errors and Paradoxes

Plausibility, Improbability, and Probability|Intuition vs.

Probability | Is there a law of averages?

Chapter 7.

social physics

Quetelet's Average Man | Correlation: A Potential Causal Indicator | Why Polls Are Wrong

Chapter 8.

How sure are you?

Conditional probability and Bayes' theorem | The probability of an actual event occurring under given conditions | Bayes' theorem and court decisions | Prosecutor's errors and lawyer's errors | From Bayes' theorem to Bayesian networks

Chapter 9.

Law and Disorder

That's Entropy | The Arrow of Time and the Second Law of Thermodynamics | The Importance of Setting Initial Conditions

Chapter 10.

The unpredictability of the predictable

Knowing the Laws Can Reduce Uncertainty | The Flapping of Seagulls' Wings and the Butterfly Effect | Providing Best Guess About the Future with Confidence Estimates | Estimating the Probability of Convergence with a Given Attractor

Chapter 11.

Weather Factory

The Butterfly Effect and Weather Forecasting | Ensemble Forecasting for Increased Accuracy | The Correlation Between Greenhouse Gases and Winter Cold Waves | Is the Climate Really Always Changing? | Global Warming and Probability | Nonlinear Dynamics, Weather, and Climate

Chapter 12.

cure

How to Collect Data | Development of Appropriate Statistical Techniques for Medical Research | Examples of Clinical Trials Using Statistical Analysis Techniques

Chapter 13.

Economic Fortune-telling

The Serious Limitations of Mathematical Models | Mathematics, Statistics, Economics, and Mathematical Economics | Can Stocks and Bonds Be Predicted? | Finance Lessons from Ecology

Chapter 14.

Our Bayesian brain

How Beliefs Are Stored in the Brain | Bayesian Theory Applied in Various Fields | Two Unique Types of Uncertainty | Humans' Learned Visual Patterns | Why We Are Manipulated by Fake News

Chapter 15.

quantum uncertainty

Wave-Particle Duality of Photons | Diverging Opinions on the Wave Function | Is Schrödinger's Cat Really Dead? | Uncertainty in Quantum Mechanics

Chapter 16.

Are dice the realm of the gods?

The Quantum World and Uncertainty | Quantum Uncertainty and Hidden Variable Theory | Keep Your Mouth Closed and Calculate | Does a Probability Distribution Always Exist in Hidden Variable Space? | The Future of Quantum Theory

Chapter 17.

Harnessing uncertainty

The Birth and Application of Monte Carlo Methods | Quantum Mechanics and Cryptographic Systems | Genetic Algorithms and Future Prediction

Chapter 18.

unknown unknown

Past, Present, and Future of Uncertainty

annotation

Image source

Search

Six Ages of Uncertainty

Why and How We Predict the Future | The Second Age of Uncertainty: Bringing Scientific Advancement | Discoveries in Probability, Statistics, and Fundamental Physics | The Fifth Age of Uncertainty and Chaos Theory | The Sixth Age of Uncertainty and Predicting the Future

Chapter 2.

Reading Animal Guts

Humanity's Desire to Predict the Future | How Human Beliefs Become Solid | From Palmistry to Skull Reading and Lottery

Chapter 3.

Rolling the dice

The Birth of Probability Theory and Dice | Mathematicians Who Were Interested in Gambling

Chapter 4.

coin toss

Limiting the Size of Uncertainty | Random Variables and Probability Distributions

Chapter 5.

Too much information

Too much data creates errors | The birth of least squares and the central limit theorem | Write down what probability does.

Chapter 6.

Errors and Paradoxes

Plausibility, Improbability, and Probability|Intuition vs.

Probability | Is there a law of averages?

Chapter 7.

social physics

Quetelet's Average Man | Correlation: A Potential Causal Indicator | Why Polls Are Wrong

Chapter 8.

How sure are you?

Conditional probability and Bayes' theorem | The probability of an actual event occurring under given conditions | Bayes' theorem and court decisions | Prosecutor's errors and lawyer's errors | From Bayes' theorem to Bayesian networks

Chapter 9.

Law and Disorder

That's Entropy | The Arrow of Time and the Second Law of Thermodynamics | The Importance of Setting Initial Conditions

Chapter 10.

The unpredictability of the predictable

Knowing the Laws Can Reduce Uncertainty | The Flapping of Seagulls' Wings and the Butterfly Effect | Providing Best Guess About the Future with Confidence Estimates | Estimating the Probability of Convergence with a Given Attractor

Chapter 11.

Weather Factory

The Butterfly Effect and Weather Forecasting | Ensemble Forecasting for Increased Accuracy | The Correlation Between Greenhouse Gases and Winter Cold Waves | Is the Climate Really Always Changing? | Global Warming and Probability | Nonlinear Dynamics, Weather, and Climate

Chapter 12.

cure

How to Collect Data | Development of Appropriate Statistical Techniques for Medical Research | Examples of Clinical Trials Using Statistical Analysis Techniques

Chapter 13.

Economic Fortune-telling

The Serious Limitations of Mathematical Models | Mathematics, Statistics, Economics, and Mathematical Economics | Can Stocks and Bonds Be Predicted? | Finance Lessons from Ecology

Chapter 14.

Our Bayesian brain

How Beliefs Are Stored in the Brain | Bayesian Theory Applied in Various Fields | Two Unique Types of Uncertainty | Humans' Learned Visual Patterns | Why We Are Manipulated by Fake News

Chapter 15.

quantum uncertainty

Wave-Particle Duality of Photons | Diverging Opinions on the Wave Function | Is Schrödinger's Cat Really Dead? | Uncertainty in Quantum Mechanics

Chapter 16.

Are dice the realm of the gods?

The Quantum World and Uncertainty | Quantum Uncertainty and Hidden Variable Theory | Keep Your Mouth Closed and Calculate | Does a Probability Distribution Always Exist in Hidden Variable Space? | The Future of Quantum Theory

Chapter 17.

Harnessing uncertainty

The Birth and Application of Monte Carlo Methods | Quantum Mechanics and Cryptographic Systems | Genetic Algorithms and Future Prediction

Chapter 18.

unknown unknown

Past, Present, and Future of Uncertainty

annotation

Image source

Search

Into the book

The first stage in which humans consciously engaged with uncertainty lasted for thousands of years.

The belief at the time was that whatever happened was God's will, and this was consistent with the evidence that soon became reality.

When the gods were happy, good things happened, and when they were angry, bad things happened.

If something good happened, it was clear that humans had pleased the gods, and if something bad happened, it was clear that humans had offended the gods through their own fault.

Thus, belief in gods became intertwined with moral obligations.

--- p.18, from “Chapter 1, ‘Six Ages of Uncertainty’”

The first true probability theories emerged when mathematicians began to carefully consider gambling and games of chance, especially the likelihood of long-term outcomes.

The pioneers of probability theory had to extract the principles of rational mathematics from the confusing mishmash of intuition, superstition, and well-founded guesses by which mankind dealt with chance events.

It was not a good idea to start by addressing complex social and scientific issues.

--- p.54, from Chapter 3, “Rolling the Dice”

The basic tools and techniques of statistics arose in the physical sciences, particularly astronomy, as a systematic way to extract the maximum amount of useful information from observations that involve unavoidable errors.

However, as our understanding of probability theory broadened and scientists gained confidence in new data analysis techniques, some pioneers began to extend these techniques beyond their original boundaries.

--- p.147, from “Chapter 7 ‘Social Physics’”

There are few things more uncertain than the weather.

But we do understand the underlying physics of weather and know the equations involved.

So why is it so difficult to predict the weather? The early pioneers of numerical weather forecasting, who attempted to predict the weather by solving equations, were all optimistic.

Tides can be predicted months in advance.

Why can't you predict the weather? No matter how powerful your computer is, long-term forecasting is impossible due to the physical nature of the situation.

All computer models are approximations, and if we're not careful, trying to approximate the equations to reality can lead to worse predictions.

--- p.237, from Chapter 11, “The Weather Factory”

Beyond practical and ethical issues, there are two challenges to setting up clinical trials.

One is statistical analysis of data generated from the test.

Another issue is the design of the experiment.

How should we structure our tests to obtain as much useful, informative, and reliable data as possible?

The technique chosen for data analysis influences what data will be collected and how.

Experimental design affects the range of data that can be collected and the reliability of the numbers.

--- p.276, from Chapter 12, “Treatment”

The stock market is more complex than horse racing, and today's traders rely on complex algorithms implemented on computers.

Many transactions are automated, with algorithms making split-second decisions without human intervention.

All these developments are driven by the desire to reduce risk by making financial issues less uncertain and more predictable.

The financial crisis happened because too many bankers thought they had it figured out.

As it turns out, they might have been better off looking into a crystal ball.

--- p.297, from Chapter 13, “Economic Fortune-telling”

Why are we so easily manipulated by fake news? It's because our Bayesian brain operates on long-held beliefs.

Our beliefs are not like computer files that can be deleted or replaced with a single click of the mouse.

It's closer to built-in hardware.

The stronger your faith, or even just the desire to believe, the more solid your faith becomes.

Every piece of fake news we believe because it suits our tastes only reinforces that ingrained connection.

Anything you don't want to believe is ignored.

--- p.343, from “Chapter 14 ‘Our Bayesian Brain’”

From a quantum perspective, which Einstein rejected, God does not roll dice, but gets the same result as if he had.

To be more precise, the universe is the result of the dice rolling itself.

Basically, quantum dice act as gods.

But are they metaphorical dice embodying true randomness, or deterministic dice bouncing chaotically within the fabric of the universe?

--- p.377, from Chapter 16, “Are Dice the Realm of God?”

Until now, uncertainty has been described as something that makes it difficult to understand what will happen in the future and can cause all well-laid plans to go awry—that is, as something that is wrong.

We looked at where uncertainty comes from, what forms it takes, how to measure it, and how to mitigate its impact.

What I haven't explained is how we can exploit uncertainty.

In fact, a little uncertainty often works to our advantage.

Although not always the same problem, uncertainty, which is often seen as a problem, can sometimes be the solution.

The belief at the time was that whatever happened was God's will, and this was consistent with the evidence that soon became reality.

When the gods were happy, good things happened, and when they were angry, bad things happened.

If something good happened, it was clear that humans had pleased the gods, and if something bad happened, it was clear that humans had offended the gods through their own fault.

Thus, belief in gods became intertwined with moral obligations.

--- p.18, from “Chapter 1, ‘Six Ages of Uncertainty’”

The first true probability theories emerged when mathematicians began to carefully consider gambling and games of chance, especially the likelihood of long-term outcomes.

The pioneers of probability theory had to extract the principles of rational mathematics from the confusing mishmash of intuition, superstition, and well-founded guesses by which mankind dealt with chance events.

It was not a good idea to start by addressing complex social and scientific issues.

--- p.54, from Chapter 3, “Rolling the Dice”

The basic tools and techniques of statistics arose in the physical sciences, particularly astronomy, as a systematic way to extract the maximum amount of useful information from observations that involve unavoidable errors.

However, as our understanding of probability theory broadened and scientists gained confidence in new data analysis techniques, some pioneers began to extend these techniques beyond their original boundaries.

--- p.147, from “Chapter 7 ‘Social Physics’”

There are few things more uncertain than the weather.

But we do understand the underlying physics of weather and know the equations involved.

So why is it so difficult to predict the weather? The early pioneers of numerical weather forecasting, who attempted to predict the weather by solving equations, were all optimistic.

Tides can be predicted months in advance.

Why can't you predict the weather? No matter how powerful your computer is, long-term forecasting is impossible due to the physical nature of the situation.

All computer models are approximations, and if we're not careful, trying to approximate the equations to reality can lead to worse predictions.

--- p.237, from Chapter 11, “The Weather Factory”

Beyond practical and ethical issues, there are two challenges to setting up clinical trials.

One is statistical analysis of data generated from the test.

Another issue is the design of the experiment.

How should we structure our tests to obtain as much useful, informative, and reliable data as possible?

The technique chosen for data analysis influences what data will be collected and how.

Experimental design affects the range of data that can be collected and the reliability of the numbers.

--- p.276, from Chapter 12, “Treatment”

The stock market is more complex than horse racing, and today's traders rely on complex algorithms implemented on computers.

Many transactions are automated, with algorithms making split-second decisions without human intervention.

All these developments are driven by the desire to reduce risk by making financial issues less uncertain and more predictable.

The financial crisis happened because too many bankers thought they had it figured out.

As it turns out, they might have been better off looking into a crystal ball.

--- p.297, from Chapter 13, “Economic Fortune-telling”

Why are we so easily manipulated by fake news? It's because our Bayesian brain operates on long-held beliefs.

Our beliefs are not like computer files that can be deleted or replaced with a single click of the mouse.

It's closer to built-in hardware.

The stronger your faith, or even just the desire to believe, the more solid your faith becomes.

Every piece of fake news we believe because it suits our tastes only reinforces that ingrained connection.

Anything you don't want to believe is ignored.

--- p.343, from “Chapter 14 ‘Our Bayesian Brain’”

From a quantum perspective, which Einstein rejected, God does not roll dice, but gets the same result as if he had.

To be more precise, the universe is the result of the dice rolling itself.

Basically, quantum dice act as gods.

But are they metaphorical dice embodying true randomness, or deterministic dice bouncing chaotically within the fabric of the universe?

--- p.377, from Chapter 16, “Are Dice the Realm of God?”

Until now, uncertainty has been described as something that makes it difficult to understand what will happen in the future and can cause all well-laid plans to go awry—that is, as something that is wrong.

We looked at where uncertainty comes from, what forms it takes, how to measure it, and how to mitigate its impact.

What I haven't explained is how we can exploit uncertainty.

In fact, a little uncertainty often works to our advantage.

Although not always the same problem, uncertainty, which is often seen as a problem, can sometimes be the solution.

--- p.415, from “Chapter 17 ‘Utilizing Uncertainty’”

Publisher's Review

★ Amazon Bestseller ★

★ Michael Faraday Award-winning author ★

★ Fellow of the Royal Society of London ★

“God does not play dice.” _Albert Einstein

According to him, everything in the world should be predictable, but

The world is still full of uncertainty!

From the era of shamanism to the era of artificial intelligence

How have humans tried to control uncertainty?

Despite the advancements in medical expertise, why were we unable to foresee the spread of infectious diseases and the prolonged nature of pandemics? Why do weather forecasts from 52 billion won supercomputers consistently receive criticism for being historically inaccurate? Can't we prevent stock market declines and losses in advance? Why, despite the emergence of powerful forecasting tools based on big data and artificial intelligence, can't we even predict the near future with perfect accuracy?

We'd love to know in advance which party will win an election, whether a prime suspect actually committed a crime, or when and how big an earthquake will strike, but whenever we try to predict the outcome of such events, our intuition is usually wrong.

Because the world is full of uncertainty and human predictability is poor.

So, is perfect control over uncertainty forever impossible? When did humanity begin its efforts to predict and control the future? How did humanity calculate uncertainty and foresee the future before technological advancements? Will hyper-predictability become possible in the Fifth Industrial Revolution?

Here's a book that will answer this question.

"God Plays Dice" is a science textbook that shows how humanity's efforts to transform an uncertain world into a certain one, encompassing everyday life, social phenomena, and even natural disasters, have led to the development of mathematics and the creation of the tool of probability over 5,000 years of history.

Probability, a tool invented to prepare for unpredictable situations,

Will he succeed in predicting the future?

This book begins by going back to the first time humans began to recognize and control uncertainty.

In doing so, it provides another answer to the question of the meaning and importance of 'uncertainty' by examining how the 'unpredictability' that has permeated human consciousness has been established as the idea of 'probability' and has systematically progressed, and how probability, which has developed into 'statistics', is applied to various fields such as mathematics, economics, medicine, psychology, and mechanics.

Uncertainty isn't always a bad thing.

We like to be surprised by unexpected and pleasant events.

I buy a lottery ticket because I want to experience the joy of striking it rich.

If we knew in advance which team would win, there would be no reason for sports or games to exist.

Yet, why has humanity, throughout its long history, sought to reduce or completely eliminate uncertainty? Because uncertainty often breeds doubt, and that doubt makes us uncomfortable.

I thought that if I could predict the near future with foresight, I could avoid trouble.

So, can probability, as a predictive tool, truly predict the future with 100 percent accuracy?

French mathematician and astronomer Pierre-Simon de Laplace said in his Philosophical Essay on Probability, “In an intelligent being there would be no uncertainty at all, and the future would unfold before his eyes as if it were the past.”

But there is one loophole here.

Predicting the future requires impossibly accurate data about the current state, even if it's only a few days ahead.

Unfortunately, however, probability is still only a tool for collecting data and increasing the accuracy of that data.

But one day we will invent a predictive tool that can see into the future with precision, free from uncertainty.

Just like developing drugs and treatments by processing massive amounts of data with high-speed computers, conducting well-designed clinical trials, and evaluating the safety of the data.

One can only hope that humanity's quest to predict the unpredictable will soon demarcate the clearly defined realms of doubt and uncertainty.

Ian Stewart, the greatest mathematics writer of our time,

Embracing the past, present, and future of humanity through the development of the history of mathematics!

Ian Stewart, Britain's leading popular mathematician, has been at the forefront of popularizing mathematics through various popular mathematics books, including "17 Equations That Changed the World" and "The Mathematics of Life," as well as through broadcasts such as the BBC and contributions to various newspapers and magazines.

A mathematician, popular science writer, and professor emeritus at the University of Warwick, he seamlessly combines mathematics with diverse fields such as history and culture for the "ordinary person" who finds mathematics difficult or dislikes it.

The story of the 'Clay Sheep Liver' artifact on display at the British Museum, the shamanism of predicting the future by looking at animal livers or tea leaves, the reason why prophets, fortune tellers, and oracles have existed since ancient times, and the practice of still believing in astrology and buying lottery tickets, etc., lead us on a journey to view the present and future through the past from an anthropological perspective.

The author, with his rich insights, ingenuity, and wit in mathematics and other fields, unravels how humanity has attempted to define, understand, and limit uncertainty, along with the development of the history of mathematics.

This book not only reveals how mathematics can help us understand the unpredictable, but also offers the most important insight: uncertainty lurks in everything, and the possibility of error always exists, even in things we think we already know.

■ Praise for this book

“I am talking about mathematics that is not pure mathematics, but mathematics that is entangled with wit, wisdom, and wonder.

“It takes us on an incredible journey, from the most ordinary to the most profound.”

_ New Scientist

“Readers interested in whether Schrödinger's cat is truly dead or whether Heisenberg's uncertainty principle is true will find themselves on a challenging but rewarding journey through the quantum world of uncertainty.”

_ 〈Publisher's Weekly〉

★ Michael Faraday Award-winning author ★

★ Fellow of the Royal Society of London ★

“God does not play dice.” _Albert Einstein

According to him, everything in the world should be predictable, but

The world is still full of uncertainty!

From the era of shamanism to the era of artificial intelligence

How have humans tried to control uncertainty?

Despite the advancements in medical expertise, why were we unable to foresee the spread of infectious diseases and the prolonged nature of pandemics? Why do weather forecasts from 52 billion won supercomputers consistently receive criticism for being historically inaccurate? Can't we prevent stock market declines and losses in advance? Why, despite the emergence of powerful forecasting tools based on big data and artificial intelligence, can't we even predict the near future with perfect accuracy?

We'd love to know in advance which party will win an election, whether a prime suspect actually committed a crime, or when and how big an earthquake will strike, but whenever we try to predict the outcome of such events, our intuition is usually wrong.

Because the world is full of uncertainty and human predictability is poor.

So, is perfect control over uncertainty forever impossible? When did humanity begin its efforts to predict and control the future? How did humanity calculate uncertainty and foresee the future before technological advancements? Will hyper-predictability become possible in the Fifth Industrial Revolution?

Here's a book that will answer this question.

"God Plays Dice" is a science textbook that shows how humanity's efforts to transform an uncertain world into a certain one, encompassing everyday life, social phenomena, and even natural disasters, have led to the development of mathematics and the creation of the tool of probability over 5,000 years of history.

Probability, a tool invented to prepare for unpredictable situations,

Will he succeed in predicting the future?

This book begins by going back to the first time humans began to recognize and control uncertainty.

In doing so, it provides another answer to the question of the meaning and importance of 'uncertainty' by examining how the 'unpredictability' that has permeated human consciousness has been established as the idea of 'probability' and has systematically progressed, and how probability, which has developed into 'statistics', is applied to various fields such as mathematics, economics, medicine, psychology, and mechanics.

Uncertainty isn't always a bad thing.

We like to be surprised by unexpected and pleasant events.

I buy a lottery ticket because I want to experience the joy of striking it rich.

If we knew in advance which team would win, there would be no reason for sports or games to exist.

Yet, why has humanity, throughout its long history, sought to reduce or completely eliminate uncertainty? Because uncertainty often breeds doubt, and that doubt makes us uncomfortable.

I thought that if I could predict the near future with foresight, I could avoid trouble.

So, can probability, as a predictive tool, truly predict the future with 100 percent accuracy?

French mathematician and astronomer Pierre-Simon de Laplace said in his Philosophical Essay on Probability, “In an intelligent being there would be no uncertainty at all, and the future would unfold before his eyes as if it were the past.”

But there is one loophole here.

Predicting the future requires impossibly accurate data about the current state, even if it's only a few days ahead.

Unfortunately, however, probability is still only a tool for collecting data and increasing the accuracy of that data.

But one day we will invent a predictive tool that can see into the future with precision, free from uncertainty.

Just like developing drugs and treatments by processing massive amounts of data with high-speed computers, conducting well-designed clinical trials, and evaluating the safety of the data.

One can only hope that humanity's quest to predict the unpredictable will soon demarcate the clearly defined realms of doubt and uncertainty.

Ian Stewart, the greatest mathematics writer of our time,

Embracing the past, present, and future of humanity through the development of the history of mathematics!

Ian Stewart, Britain's leading popular mathematician, has been at the forefront of popularizing mathematics through various popular mathematics books, including "17 Equations That Changed the World" and "The Mathematics of Life," as well as through broadcasts such as the BBC and contributions to various newspapers and magazines.

A mathematician, popular science writer, and professor emeritus at the University of Warwick, he seamlessly combines mathematics with diverse fields such as history and culture for the "ordinary person" who finds mathematics difficult or dislikes it.

The story of the 'Clay Sheep Liver' artifact on display at the British Museum, the shamanism of predicting the future by looking at animal livers or tea leaves, the reason why prophets, fortune tellers, and oracles have existed since ancient times, and the practice of still believing in astrology and buying lottery tickets, etc., lead us on a journey to view the present and future through the past from an anthropological perspective.

The author, with his rich insights, ingenuity, and wit in mathematics and other fields, unravels how humanity has attempted to define, understand, and limit uncertainty, along with the development of the history of mathematics.

This book not only reveals how mathematics can help us understand the unpredictable, but also offers the most important insight: uncertainty lurks in everything, and the possibility of error always exists, even in things we think we already know.

■ Praise for this book

“I am talking about mathematics that is not pure mathematics, but mathematics that is entangled with wit, wisdom, and wonder.

“It takes us on an incredible journey, from the most ordinary to the most profound.”

_ New Scientist

“Readers interested in whether Schrödinger's cat is truly dead or whether Heisenberg's uncertainty principle is true will find themselves on a challenging but rewarding journey through the quantum world of uncertainty.”

_ 〈Publisher's Weekly〉

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: August 19, 2020

- Page count, weight, size: 472 pages | 714g | 152*225*22mm

- ISBN13: 9791188850969

- ISBN10: 1188850962

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)