The Neuroscience of Memory

|

Description

Book Introduction

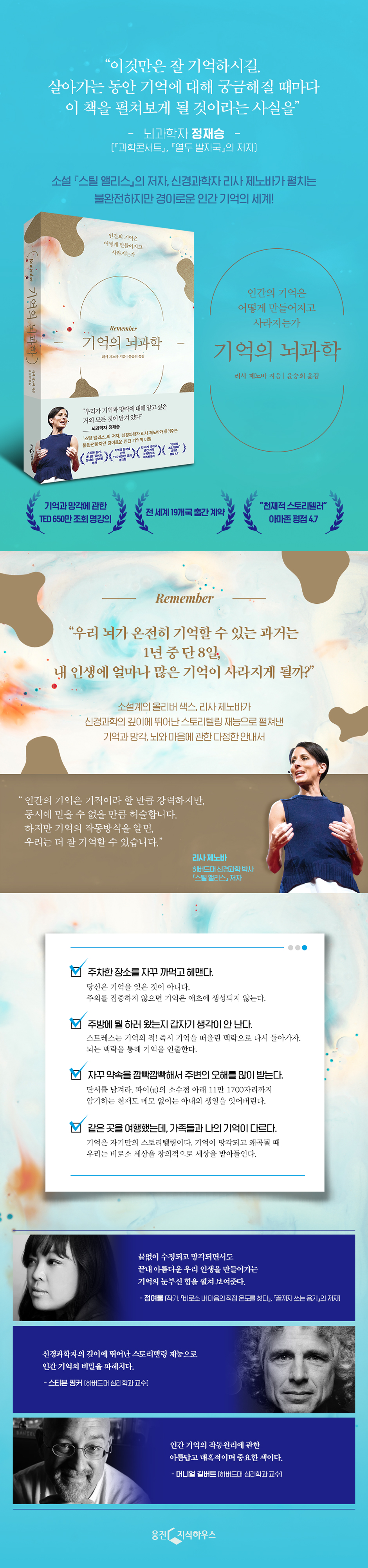

“What we want to know about memory and forgetting “Almost everything is contained” _ Neuroscientist Jaeseung Jeong Lisa Genova, neuroscientist and author of Still Alice, tells us: The Secret of Imperfect and Wonderful Human Memory Why do we remember our first kiss but not our tenth? The day of the 9/11 terrorist attacks is still vivid, but why is yesterday's events completely forgotten? If you frequently forget things like what you were going to say or where you parked, should you suspect Alzheimer's disease? Why world-renowned musician Yo-Yo Ma left his $3 million cello in a taxi Can anyone become a memory genius just by training? Have you ever felt your heart sink because you couldn't remember where you parked, the name of an acquaintance, or what you were about to say? It's too early to worry. You do not have Alzheimer's disease. Your memory is working normally, you just haven't been paying attention. Lisa Genova, author of the novel "Still Alice," the original film of the same name, and a Harvard University neuroscientist, meets Korean readers with "Remember," a neuroscience textbook that covers everything about memory and forgetting. According to this book, memory is a process of reconstructing one's own story by selecting and reinforcing what we consider meaningful, much like cultivating a forest. When memories are distorted and forgotten, humans can rather accept the world in a more individualistic and creative way. Drawing on the depth of a neuroscientist's experience and exceptional storytelling talent, the author guides us into the imperfect and wondrous world of human memory. And it provides a path to a fundamentally better memory life, including attention, emotions, sleep, context, and stress. |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommendation

Introductory remarks: Powerful enough to be called a miracle, yet incredibly fragile.

Part 1: The Science of Memory

1 How are memories made?

2 Reasons why you forgot where you parked

3. Working memory at this moment

4 Muscle Memory: What Your Body Remembers

5 Semantic Memory, the Encyclopedia in My Head

6 Flashpoint Memories, That Unforgettable Event

Part 2: The Art of Forgetting

7.

Our memories are wrong

8.

When memories linger on the tip of your tongue

9.

How to remember what you need to remember

10.

How many memories will disappear in life?

11.

Forgetting keeps us alive

12.

Aging and its fate

13.

Alzheimer's disease, the most feared future

Part 3: How to Cultivate a Forest of Memories

14.

Back to context

15.

Is stress a cure or a poison?

16.

What Happens When You're Sleep Deprived

17.

The brain that resists Alzheimer's disease

18.

Preciously, but never heavy

Appendix: Things You Can Do to Remember

Further Reading

Acknowledgements

Introductory remarks: Powerful enough to be called a miracle, yet incredibly fragile.

Part 1: The Science of Memory

1 How are memories made?

2 Reasons why you forgot where you parked

3. Working memory at this moment

4 Muscle Memory: What Your Body Remembers

5 Semantic Memory, the Encyclopedia in My Head

6 Flashpoint Memories, That Unforgettable Event

Part 2: The Art of Forgetting

7.

Our memories are wrong

8.

When memories linger on the tip of your tongue

9.

How to remember what you need to remember

10.

How many memories will disappear in life?

11.

Forgetting keeps us alive

12.

Aging and its fate

13.

Alzheimer's disease, the most feared future

Part 3: How to Cultivate a Forest of Memories

14.

Back to context

15.

Is stress a cure or a poison?

16.

What Happens When You're Sleep Deprived

17.

The brain that resists Alzheimer's disease

18.

Preciously, but never heavy

Appendix: Things You Can Do to Remember

Further Reading

Acknowledgements

Detailed image

Into the book

When I weave together the anecdotes that are most meaningful to me, it becomes the story of my life.

Memories gathered together like this are called autobiographical memories.

These include major life events such as your first kiss, the day you scored the winning goal, your college graduation, your wedding day, the day you moved into your first home, a big promotion, and the birth of a child.

The meaningful moments contained in each autobiographical memory are not necessarily scenes from a rainbow-colored, mysterious fairy tale.

What you remember determines what story you choose to tell about your life.

We tend to store memories that align with our identity and outlook on life.

---From "Chapter 6: Flash Memory, That Unforgettable Incident"

If we truly value memory, we will acknowledge its true greatness and take good care of it.

With the right tools, your memory will reach its limitless potential.

So we can learn a new language, learn to play the guitar, and get an A on a test.

We will appreciate the true value of memories, and this gratitude, as numerous studies have shown, contributes to our happiness and well-being.

At the same time, if we take memory lightly, we will become more relaxed and tolerant of its many flaws.

---From "Chapter 18: Preciously, but Never Heavyly"

In 1980, my father took a job as vice president of development at a high-tech company.

My father, who was filling out the necessary documents with the HR manager, filled in the phone number section without hesitation, but then got stuck at the address section.

I didn't know the name of the neighborhood I'd been living in for five years.

It wasn't because he was an old man with Alzheimer's disease.

At the time, my father was only 39 years old and a brilliant corporate executive.

"I don't know.

“I’ll give you my number, so ask my wife.” My father still makes excuses about that incident.

“Who lives their life worrying about such details?” How could someone not know their own home address, which they have visited 1,825 times over the past five years?

---From "Chapter 2: Why You Forgot Where You Parked"

Information cannot remain in working memory for long.

Visual information is stored in the spatiotemporal notebook, and auditory information is stored in the phonological loop for only about 15 to 30 seconds.

That's it.

Information that has been stored gives way to new information.

Life is something new happening every moment.

We are constantly hearing, seeing, thinking, and experiencing what is happening inside and outside of us (aren't we constantly talking to ourselves inside? I just answered that question).

As the next piece of data enters working memory, whatever came in first is pushed out.

If the sentence I'm typing right now is the last sentence in this book, or if the text I haven't read yet is about Jessica Chastain wanting to star in a movie adaptation of my novel, or if I write about this moment in my book and reread and revise it dozens of times, the information I perceive and deem important in this moment will be transferred from the temporary space of working memory to the hippocampus.

Then, in the hippocampus, neurons connect scattered, fleeting sensory information to weave together a single memory of what happened in our kitchen today.

This moment is no longer a memory that will disappear in 30 seconds.

I may remember this moment for decades to come.

---From "Chapter 3: This Moment, Working Memory"

"Remember when you went on a hot air balloon ride? You lost your parents at the mall when you were six? You spilled a red drink on your bride's dress at your cousin's wedding?" Researchers asked participants similar questions about events that never actually happened, then presented them with Photoshopped photos and false information to support the events, all to make them seem completely fake.

How did participants react to the fabricated stories? Twenty-five to fifty percent of participants claimed to recall detailed experiences they hadn't experienced.

---From "Chapter 7 Our Memories Are False"

As you reflect on your day, consider which experiences or pieces of information are meaningful enough to stand the test of time.

Is there anything I learned or experienced today that will stick with me tomorrow, next week, next year, or even twenty years from now? Or will today fade into obscurity, to the bottom of Ebbinghaus's forgetting curve? How many days of my life will be erased forever? - Chapter 10: How many memories will be lost in life?

So, what should we do if we want to forget a memory that has already been consolidated and stored in long-term memory? In this case, we should avoid exposure to cues and contexts that could trigger information retrieval.

Don't go to such places, don't think about such memories, and don't even mention them.

You shouldn't unconsciously recall such memories.

If you find yourself humming annoying commercial music without realizing it, stop singing immediately.

Stop, stop.

You shouldn't sing until the end.

Change your thinking.

Resist the activation of the neural circuits of unwanted memories.

Each time you completely withdraw, the memory becomes stronger.

The more memories are left alone, the weaker and more forgotten they become.

---From "Chapter 11: Forgetting Makes Us Live"

Alzheimer's disease begins by interfering with the formation of new memories, but eventually, in perhaps the most tragic way, it destroys the neural networks that store the oldest memories already made.

By this stage, my grandmother no longer recognized me.

I'm afraid that there will come a day when Greg won't remember me.

Because there is no cure, that sad day will come someday.

It takes an average of eight to ten years for Alzheimer's disease to progress from the first symptoms of memory loss to the final stage.

Ultimately, the ability to create and retrieve all kinds of memories is severely impaired.

Memory loss from Alzheimer's disease is widespread, devastating, tragic, and not a natural part of aging.

Memories gathered together like this are called autobiographical memories.

These include major life events such as your first kiss, the day you scored the winning goal, your college graduation, your wedding day, the day you moved into your first home, a big promotion, and the birth of a child.

The meaningful moments contained in each autobiographical memory are not necessarily scenes from a rainbow-colored, mysterious fairy tale.

What you remember determines what story you choose to tell about your life.

We tend to store memories that align with our identity and outlook on life.

---From "Chapter 6: Flash Memory, That Unforgettable Incident"

If we truly value memory, we will acknowledge its true greatness and take good care of it.

With the right tools, your memory will reach its limitless potential.

So we can learn a new language, learn to play the guitar, and get an A on a test.

We will appreciate the true value of memories, and this gratitude, as numerous studies have shown, contributes to our happiness and well-being.

At the same time, if we take memory lightly, we will become more relaxed and tolerant of its many flaws.

---From "Chapter 18: Preciously, but Never Heavyly"

In 1980, my father took a job as vice president of development at a high-tech company.

My father, who was filling out the necessary documents with the HR manager, filled in the phone number section without hesitation, but then got stuck at the address section.

I didn't know the name of the neighborhood I'd been living in for five years.

It wasn't because he was an old man with Alzheimer's disease.

At the time, my father was only 39 years old and a brilliant corporate executive.

"I don't know.

“I’ll give you my number, so ask my wife.” My father still makes excuses about that incident.

“Who lives their life worrying about such details?” How could someone not know their own home address, which they have visited 1,825 times over the past five years?

---From "Chapter 2: Why You Forgot Where You Parked"

Information cannot remain in working memory for long.

Visual information is stored in the spatiotemporal notebook, and auditory information is stored in the phonological loop for only about 15 to 30 seconds.

That's it.

Information that has been stored gives way to new information.

Life is something new happening every moment.

We are constantly hearing, seeing, thinking, and experiencing what is happening inside and outside of us (aren't we constantly talking to ourselves inside? I just answered that question).

As the next piece of data enters working memory, whatever came in first is pushed out.

If the sentence I'm typing right now is the last sentence in this book, or if the text I haven't read yet is about Jessica Chastain wanting to star in a movie adaptation of my novel, or if I write about this moment in my book and reread and revise it dozens of times, the information I perceive and deem important in this moment will be transferred from the temporary space of working memory to the hippocampus.

Then, in the hippocampus, neurons connect scattered, fleeting sensory information to weave together a single memory of what happened in our kitchen today.

This moment is no longer a memory that will disappear in 30 seconds.

I may remember this moment for decades to come.

---From "Chapter 3: This Moment, Working Memory"

"Remember when you went on a hot air balloon ride? You lost your parents at the mall when you were six? You spilled a red drink on your bride's dress at your cousin's wedding?" Researchers asked participants similar questions about events that never actually happened, then presented them with Photoshopped photos and false information to support the events, all to make them seem completely fake.

How did participants react to the fabricated stories? Twenty-five to fifty percent of participants claimed to recall detailed experiences they hadn't experienced.

---From "Chapter 7 Our Memories Are False"

As you reflect on your day, consider which experiences or pieces of information are meaningful enough to stand the test of time.

Is there anything I learned or experienced today that will stick with me tomorrow, next week, next year, or even twenty years from now? Or will today fade into obscurity, to the bottom of Ebbinghaus's forgetting curve? How many days of my life will be erased forever? - Chapter 10: How many memories will be lost in life?

So, what should we do if we want to forget a memory that has already been consolidated and stored in long-term memory? In this case, we should avoid exposure to cues and contexts that could trigger information retrieval.

Don't go to such places, don't think about such memories, and don't even mention them.

You shouldn't unconsciously recall such memories.

If you find yourself humming annoying commercial music without realizing it, stop singing immediately.

Stop, stop.

You shouldn't sing until the end.

Change your thinking.

Resist the activation of the neural circuits of unwanted memories.

Each time you completely withdraw, the memory becomes stronger.

The more memories are left alone, the weaker and more forgotten they become.

---From "Chapter 11: Forgetting Makes Us Live"

Alzheimer's disease begins by interfering with the formation of new memories, but eventually, in perhaps the most tragic way, it destroys the neural networks that store the oldest memories already made.

By this stage, my grandmother no longer recognized me.

I'm afraid that there will come a day when Greg won't remember me.

Because there is no cure, that sad day will come someday.

It takes an average of eight to ten years for Alzheimer's disease to progress from the first symptoms of memory loss to the final stage.

Ultimately, the ability to create and retrieve all kinds of memories is severely impaired.

Memory loss from Alzheimer's disease is widespread, devastating, tragic, and not a natural part of aging.

---From "Chapter 13 Alzheimer's Disease, the Most Fearful Future"

Publisher's Review

Have you ever felt your heart sink because you couldn't remember where you parked, the name of an acquaintance, or what you were about to say? It's too early to worry.

You do not have Alzheimer's disease.

Your memory is working normally, you just haven't been paying attention.

Lisa Genova, author of the novel "Still Alice," the original film of the same name, and a Harvard University neuroscientist, meets Korean readers with "Remember," a neuroscience textbook that covers everything about memory and forgetting.

According to this book, memory is a process of reconstructing one's own story by selecting and reinforcing what we consider meaningful, much like cultivating a forest.

When memories are distorted and forgotten, humans can rather accept the world in a more individualistic and creative way.

Drawing on the depth of a neuroscientist's experience and exceptional storytelling talent, the author guides us into the imperfect and wondrous world of human memory.

And it provides a path to a fundamentally better memory life, including attention, emotions, sleep, context, and stress.

1.

"The miraculously powerful yet incredibly fragile world of human memory."

- Everything about memory and forgetting from Lisa Genova, the Oliver Sacks of the novel world.

One in ten people over 65 in Korea suffer from dementia, and this number is expected to increase rapidly, exceeding one million by 2024 (2021 Dementia Prevalence Survey).

Harvard neuroscientist Dr. Lisa Genova warns of the terrifying reality we are about to face.

“If you are reassured that you do not have dementia, you will be living as a caregiver for a person with dementia.” Lisa Genova is the author of the original novel for the film [Still Alice], which depicts the crumbling life of a middle-aged female professor with Alzheimer’s disease. She has contributed to the public’s understanding of memory and Alzheimer’s disease through various lectures for the past 10 years.

He reveals that people of all generations who come to his lectures express excessive guilt and fear, saying things like, "How could I forget that?" or "If I were younger, I wouldn't have forgotten it."

Genova emphasizes that everyday forgetfulness should be distinguished from signs of Alzheimer's disease, and furthermore, that understanding the principles of how memories are stored and erased can free us from such fears and lead to a better memory life.

In his new nonfiction book, The Neuroscience of Memory, he draws on his neuroscientist expertise and remarkable storytelling skills to guide us into the imperfect but wondrous world of human memory.

According to this book, the human brain is not designed to remember and store everything, and forgetting is not a disease we must avoid, but a perfectly normal state of evolution.

Furthermore, memory is redefined as the sum total of what we remember and what we forget.

This book not only encompasses landmark neuroscientific research and fascinating clinical cases to aid in the neuroscientific understanding of memory and forgetting, but also explores the relationship between memory and attention, emotion, sleep, context, and stress, offering fundamental and practical tips for improving memory.

As we follow this captivating storytelling about memory, we come to understand that remembering and forgetting are both sophisticated sciences and the art of creatively cultivating our lives.

2.

“How can someone tell the story of how human memory works so captivatingly?”

Uncovering the secrets of memory through a combination of neuroscientific knowledge and masterful storytelling.

What memories are stored in our brains, and which ones are forgotten? We may not remember our tenth kiss, but we still vividly remember our first.

I hesitate to answer the question of what I did last night, but the atmosphere on my morning commute on April 16, 2014, when the news broke, still lingers in my mind.

According to this book, this phenomenon occurs because the brain does not store memories uniformly in a specific area, but processes and stores different types of memories in different ways.

The human brain remembers more easily the special things, the things we focus our attention on and find meaningful, than the everyday things.

That's why we remember events that were completely unexpected or that brought about strong emotions like shock, emotion, sadness, or fear, like the Boston Marathon or the 9/11 terrorist attacks, more vividly than events that happened yesterday.

This is called a 'flashlight memory'.

"Autobiographical memories" of major life events, such as college graduations, weddings, and the birth of children, vary depending on an individual's identity and outlook on life, reflecting their perspective on how they want to tell their life's story (Chapter 6).

On the other hand, 'semantic memory', which is an encyclopedic memory of learned experiences and knowledge, is strengthened through techniques such as repetition, memorization at intervals of time, self-testing, and visual-spatial visualization (Chapter 5).

'Muscle memory', which is ingrained in our body and we unconsciously recall actions such as walking, running, and driving, not only allows us to eat, drink, and carry out our daily lives without being conscious of it, but also helps us contribute to higher-level activities (Chapter 4).

The '10,000-hour rule', which states that one can become an expert through repeated training, is a message of self-development and a representative example of understanding and actively utilizing how memory works.

Understanding how memories are stored and lost not only allows us to train our memory effectively, but also greatly improves our lives by enabling efficient learning and creative activities.

3.

“Everyone has a forest of memories to cultivate.”

_ A memory that lasts only 8 days in a year.

Forgetting is not a disease, it's a choice and a blessing.

Akira Haraguchi, who entered the Guinness Book of World Records by memorizing 111,700 decimal places of pi (π) at the age of 69, forgot his wife's wedding anniversary despite having such an amazing memory.

World-renowned cellist Yo-Yo Ma left his most prized cello, worth 3 billion won, in the trunk of a taxi, and American doctors left 772 surgical instruments in a patient's body and sutured them over the course of 8 years (Joint Commission, 2013).

Why on earth do they do this? Is it because they're indifferent to their wives? Is it because the doctors have personal problems? That's not true.

There just weren't any clues.

Memories about things we need to remember in the future are called 'prospective memories', but our brain is particularly prone to forgetting these future memories.

The author encourages us that we can maintain prospective memories simply by leaving clues that trigger memories and placing them in prominent places (Chapter 9).

In this way, human memory is both incredibly capable and incredibly imperfect.

The average person only remembers the details of eight to ten days in a year, and that number drops even further when you go back five years.

What is even more surprising is that even the remaining memories are incomplete and inaccurate, so there is a high possibility that they have been omitted or unintentionally edited.

As episodic memories are strengthened into long-term memories, they are edited by imagination, opinions, and speculation, and are forgotten and distorted by emotions, reading and hearing, and dreams.

In one memory experiment conducted after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, subjects were asked to describe what they remembered about a video of a plane crashing in a Pennsylvania field.

They answered honestly and specifically about what they saw.

The plane that crashed in Pennsylvania never existed in the first place.

Questions that elicit such specific answers can trick our brains into believing that we remember events we've never experienced (Chapter 7).

Nevertheless, the author emphasizes that forgetting is not a sign of aging, a symptom of dementia, a shameful incompetence, or a maladaptive problem to be solved, but rather a natural brain activity and, for some, a blessing.

Rather, it is better to forget things like misinformation, ingrained bad habits, and increasingly intensifying traumas like war or sexual violence.

It is theoretically possible to soften the pain by deliberately turning a terrible memory into a good one and avoiding activating the memory.

By letting go of past memories, we can learn new experiences and move forward, and we retain meaningful memories for longer.

Ultimately, memory and forgetting are processes of completing one's own narrative by selecting and reinforcing what is meaningful to each individual.

4.

Beyond the fear of Alzheimer's, for a life brighter than your memories.

How to build a brain that resists Alzheimer's disease, including attention, sleep, and stress.

When we look at people who have lost their personal history to Alzheimer's disease, we intuitively understand how central memory is to experiencing a truly human life.

Greg O'Brien, the author's longtime friend and the protagonist of the novel Inside O'Briens, also suffers from Alzheimer's disease.

The newspaper reporter couldn't even remember where he had parked his car to get to the meeting place, let alone the fact that he had driven a jeep.

While holding your phone and keys in your hand and searching for them is simply forgetfulness, not being able to recognize what they are for is a symptom of Alzheimer's disease.

The vague fear that one day one might develop Alzheimer's disease is like an urban legend that suddenly strikes not only the elderly, but also middle-aged people experiencing aging, and the younger generation who cannot be separated from digital devices.

The author advises that instead of panicking and stressing over a word or name that suddenly doesn't come to mind, people should instead use Google searches.

Rather, stress and lack of sleep can cause fatal damage to human memory and increase the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease by causing amyloid accumulation.

Rather than relying on hypotheses that suggest things like wine, chocolate, puzzles, and card games are good for preventing Alzheimer's, you can approach a brain that resists Alzheimer's by accessing new information through reading or meeting new people, and by getting enough sleep, eating a healthy diet, and living a stress-free life.

The most important thing is to remember that even though countless moments in life are forgotten, it is a process to remember tomorrow better than yesterday.

Like Genoa's grandmother, who remained loving and adored until the very end despite suffering from Alzheimer's disease, or O'Brien, who struggled to write beautiful sentences even as his vocabulary faded, the author consoles us by reminding us that even in moments of memory loss, you will still be yourself.

This book, which captures the wondrous process of memory ascending to the realm of art, has become a story that goes beyond science and becomes closer to literature thanks to the warm sensibility of Lisa Genova, the 'alchemist of memory.'

You do not have Alzheimer's disease.

Your memory is working normally, you just haven't been paying attention.

Lisa Genova, author of the novel "Still Alice," the original film of the same name, and a Harvard University neuroscientist, meets Korean readers with "Remember," a neuroscience textbook that covers everything about memory and forgetting.

According to this book, memory is a process of reconstructing one's own story by selecting and reinforcing what we consider meaningful, much like cultivating a forest.

When memories are distorted and forgotten, humans can rather accept the world in a more individualistic and creative way.

Drawing on the depth of a neuroscientist's experience and exceptional storytelling talent, the author guides us into the imperfect and wondrous world of human memory.

And it provides a path to a fundamentally better memory life, including attention, emotions, sleep, context, and stress.

1.

"The miraculously powerful yet incredibly fragile world of human memory."

- Everything about memory and forgetting from Lisa Genova, the Oliver Sacks of the novel world.

One in ten people over 65 in Korea suffer from dementia, and this number is expected to increase rapidly, exceeding one million by 2024 (2021 Dementia Prevalence Survey).

Harvard neuroscientist Dr. Lisa Genova warns of the terrifying reality we are about to face.

“If you are reassured that you do not have dementia, you will be living as a caregiver for a person with dementia.” Lisa Genova is the author of the original novel for the film [Still Alice], which depicts the crumbling life of a middle-aged female professor with Alzheimer’s disease. She has contributed to the public’s understanding of memory and Alzheimer’s disease through various lectures for the past 10 years.

He reveals that people of all generations who come to his lectures express excessive guilt and fear, saying things like, "How could I forget that?" or "If I were younger, I wouldn't have forgotten it."

Genova emphasizes that everyday forgetfulness should be distinguished from signs of Alzheimer's disease, and furthermore, that understanding the principles of how memories are stored and erased can free us from such fears and lead to a better memory life.

In his new nonfiction book, The Neuroscience of Memory, he draws on his neuroscientist expertise and remarkable storytelling skills to guide us into the imperfect but wondrous world of human memory.

According to this book, the human brain is not designed to remember and store everything, and forgetting is not a disease we must avoid, but a perfectly normal state of evolution.

Furthermore, memory is redefined as the sum total of what we remember and what we forget.

This book not only encompasses landmark neuroscientific research and fascinating clinical cases to aid in the neuroscientific understanding of memory and forgetting, but also explores the relationship between memory and attention, emotion, sleep, context, and stress, offering fundamental and practical tips for improving memory.

As we follow this captivating storytelling about memory, we come to understand that remembering and forgetting are both sophisticated sciences and the art of creatively cultivating our lives.

2.

“How can someone tell the story of how human memory works so captivatingly?”

Uncovering the secrets of memory through a combination of neuroscientific knowledge and masterful storytelling.

What memories are stored in our brains, and which ones are forgotten? We may not remember our tenth kiss, but we still vividly remember our first.

I hesitate to answer the question of what I did last night, but the atmosphere on my morning commute on April 16, 2014, when the news broke, still lingers in my mind.

According to this book, this phenomenon occurs because the brain does not store memories uniformly in a specific area, but processes and stores different types of memories in different ways.

The human brain remembers more easily the special things, the things we focus our attention on and find meaningful, than the everyday things.

That's why we remember events that were completely unexpected or that brought about strong emotions like shock, emotion, sadness, or fear, like the Boston Marathon or the 9/11 terrorist attacks, more vividly than events that happened yesterday.

This is called a 'flashlight memory'.

"Autobiographical memories" of major life events, such as college graduations, weddings, and the birth of children, vary depending on an individual's identity and outlook on life, reflecting their perspective on how they want to tell their life's story (Chapter 6).

On the other hand, 'semantic memory', which is an encyclopedic memory of learned experiences and knowledge, is strengthened through techniques such as repetition, memorization at intervals of time, self-testing, and visual-spatial visualization (Chapter 5).

'Muscle memory', which is ingrained in our body and we unconsciously recall actions such as walking, running, and driving, not only allows us to eat, drink, and carry out our daily lives without being conscious of it, but also helps us contribute to higher-level activities (Chapter 4).

The '10,000-hour rule', which states that one can become an expert through repeated training, is a message of self-development and a representative example of understanding and actively utilizing how memory works.

Understanding how memories are stored and lost not only allows us to train our memory effectively, but also greatly improves our lives by enabling efficient learning and creative activities.

3.

“Everyone has a forest of memories to cultivate.”

_ A memory that lasts only 8 days in a year.

Forgetting is not a disease, it's a choice and a blessing.

Akira Haraguchi, who entered the Guinness Book of World Records by memorizing 111,700 decimal places of pi (π) at the age of 69, forgot his wife's wedding anniversary despite having such an amazing memory.

World-renowned cellist Yo-Yo Ma left his most prized cello, worth 3 billion won, in the trunk of a taxi, and American doctors left 772 surgical instruments in a patient's body and sutured them over the course of 8 years (Joint Commission, 2013).

Why on earth do they do this? Is it because they're indifferent to their wives? Is it because the doctors have personal problems? That's not true.

There just weren't any clues.

Memories about things we need to remember in the future are called 'prospective memories', but our brain is particularly prone to forgetting these future memories.

The author encourages us that we can maintain prospective memories simply by leaving clues that trigger memories and placing them in prominent places (Chapter 9).

In this way, human memory is both incredibly capable and incredibly imperfect.

The average person only remembers the details of eight to ten days in a year, and that number drops even further when you go back five years.

What is even more surprising is that even the remaining memories are incomplete and inaccurate, so there is a high possibility that they have been omitted or unintentionally edited.

As episodic memories are strengthened into long-term memories, they are edited by imagination, opinions, and speculation, and are forgotten and distorted by emotions, reading and hearing, and dreams.

In one memory experiment conducted after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, subjects were asked to describe what they remembered about a video of a plane crashing in a Pennsylvania field.

They answered honestly and specifically about what they saw.

The plane that crashed in Pennsylvania never existed in the first place.

Questions that elicit such specific answers can trick our brains into believing that we remember events we've never experienced (Chapter 7).

Nevertheless, the author emphasizes that forgetting is not a sign of aging, a symptom of dementia, a shameful incompetence, or a maladaptive problem to be solved, but rather a natural brain activity and, for some, a blessing.

Rather, it is better to forget things like misinformation, ingrained bad habits, and increasingly intensifying traumas like war or sexual violence.

It is theoretically possible to soften the pain by deliberately turning a terrible memory into a good one and avoiding activating the memory.

By letting go of past memories, we can learn new experiences and move forward, and we retain meaningful memories for longer.

Ultimately, memory and forgetting are processes of completing one's own narrative by selecting and reinforcing what is meaningful to each individual.

4.

Beyond the fear of Alzheimer's, for a life brighter than your memories.

How to build a brain that resists Alzheimer's disease, including attention, sleep, and stress.

When we look at people who have lost their personal history to Alzheimer's disease, we intuitively understand how central memory is to experiencing a truly human life.

Greg O'Brien, the author's longtime friend and the protagonist of the novel Inside O'Briens, also suffers from Alzheimer's disease.

The newspaper reporter couldn't even remember where he had parked his car to get to the meeting place, let alone the fact that he had driven a jeep.

While holding your phone and keys in your hand and searching for them is simply forgetfulness, not being able to recognize what they are for is a symptom of Alzheimer's disease.

The vague fear that one day one might develop Alzheimer's disease is like an urban legend that suddenly strikes not only the elderly, but also middle-aged people experiencing aging, and the younger generation who cannot be separated from digital devices.

The author advises that instead of panicking and stressing over a word or name that suddenly doesn't come to mind, people should instead use Google searches.

Rather, stress and lack of sleep can cause fatal damage to human memory and increase the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease by causing amyloid accumulation.

Rather than relying on hypotheses that suggest things like wine, chocolate, puzzles, and card games are good for preventing Alzheimer's, you can approach a brain that resists Alzheimer's by accessing new information through reading or meeting new people, and by getting enough sleep, eating a healthy diet, and living a stress-free life.

The most important thing is to remember that even though countless moments in life are forgotten, it is a process to remember tomorrow better than yesterday.

Like Genoa's grandmother, who remained loving and adored until the very end despite suffering from Alzheimer's disease, or O'Brien, who struggled to write beautiful sentences even as his vocabulary faded, the author consoles us by reminding us that even in moments of memory loss, you will still be yourself.

This book, which captures the wondrous process of memory ascending to the realm of art, has become a story that goes beyond science and becomes closer to literature thanks to the warm sensibility of Lisa Genova, the 'alchemist of memory.'

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: April 15, 2022

- Page count, weight, size: 280 pages | 360g | 135*210*20mm

- ISBN13: 9788901259727

- ISBN10: 8901259729

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)