The Future of Senses

|

Description

Book Introduction

Lee Jeong-mo, director of the Seoul Metropolitan Science Museum, strongly recommends Professor Jeong Jae-seung from KAIST!

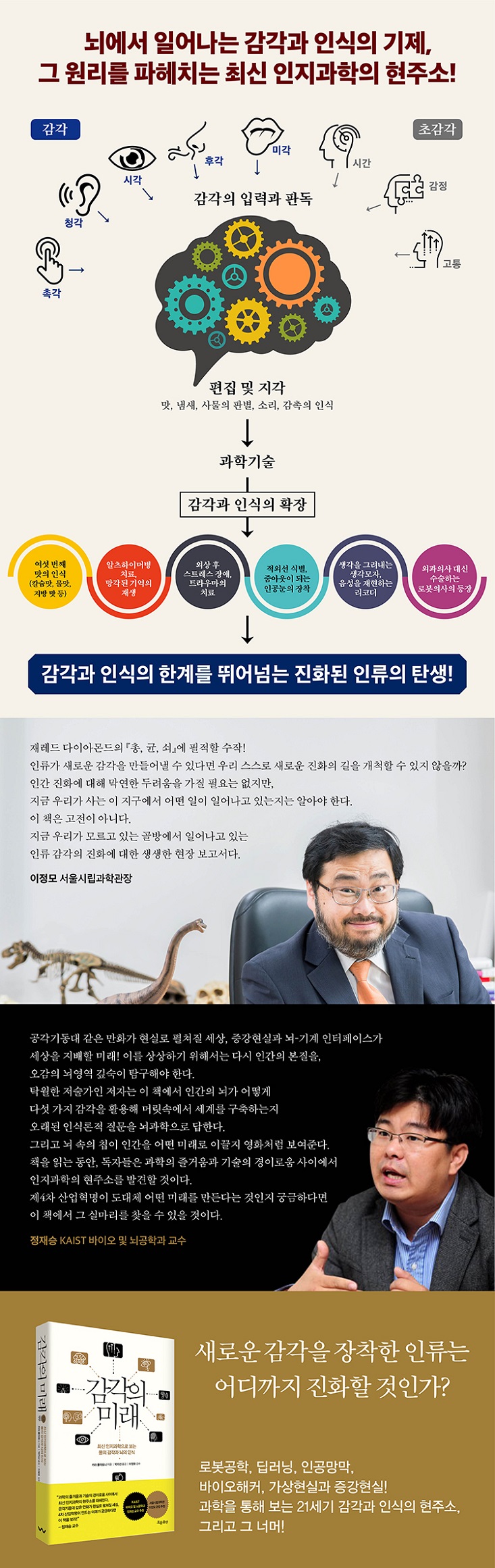

A renowned science journalist reveals the connection between the body's senses and the brain through cutting-edge cognitive science!

We perceive the world through our bodily senses: seeing, hearing, tasting, touching, and smelling.

The brain, weighing 1.4 kilograms, controls all these senses and perceptions.

So, by what principle does the brain receive external sensations and transmit them back to us?

The author of this book, Kara Platoni, is a journalist and author who has won numerous prestigious awards, including the Ebert Clarke/Seth Payne Award for Young Science Journalists.

She taught reporting and narrative writing at the University of California, Berkeley, but left school to write this book and spent three years traveling around the United States, Germany, England, and France to research the material.

She questioned what happens in the human brain during contact with the outside world, and whether, despite the brain's limited cognitive abilities, it is possible to enhance or alter our ability to perceive the world.

She met with a wide range of people, including neuroscientists, engineers, psychologists, geneticists, surgeons, transhumanists, futurists, ethicists, chefs, and perfumers, and gathered a vast amount of data, which she incorporated into this book.

A renowned science journalist reveals the connection between the body's senses and the brain through cutting-edge cognitive science!

We perceive the world through our bodily senses: seeing, hearing, tasting, touching, and smelling.

The brain, weighing 1.4 kilograms, controls all these senses and perceptions.

So, by what principle does the brain receive external sensations and transmit them back to us?

The author of this book, Kara Platoni, is a journalist and author who has won numerous prestigious awards, including the Ebert Clarke/Seth Payne Award for Young Science Journalists.

She taught reporting and narrative writing at the University of California, Berkeley, but left school to write this book and spent three years traveling around the United States, Germany, England, and France to research the material.

She questioned what happens in the human brain during contact with the outside world, and whether, despite the brain's limited cognitive abilities, it is possible to enhance or alter our ability to perceive the world.

She met with a wide range of people, including neuroscientists, engineers, psychologists, geneticists, surgeons, transhumanists, futurists, ethicists, chefs, and perfumers, and gathered a vast amount of data, which she incorporated into this book.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Reviewer's note

prolog

Part 1: The Five Senses: Five Pathways to the World

Chapter 1: Taste: A Journey to Discover the Sixth Taste

Attracting Tastes, Repulsive Tastes | Perception First, Language First | The Periodic Table of Tastes | The Taste of Brown | Tastes Created by Time | The Alchemy of Taste

Chapter 2_ Olfaction: Scents that evoke memories and emotions

Olfactory Therapy | The Proust Effect | The Correlation Between Smell and Emotion | The Topography of Smell | Olfactory and Alzheimer's | Linguistic Definitions, Cultural Associations, and Personal Memory | A Journey into the Past

Chapter 3: Vision: A World Without Light, and Beyond

A World of Reflection and Contrast | Perceiving Through Images | A Second Eye | Reading the World Through Electronic Language | Guinea Pigs, Not Patients

Chapter 4: Hearing: Electrical Signals That Draw Thoughts

The Thought-Reading Hat | From Ear to Brain | Auditory Imagery | Stimulus Reconstruction | The Age of Surveillance

Chapter 5: Touch: The Operating Room Without a Doctor

Replacing sight with touch | First-generation surgical robots | Surgery performed with thoughts, not hands | The brain, a black box

Part 2: Extrasensory Perception: The World Inside Your Head

Chapter 6_ Time: A Clock That Lasts 10,000 Years

The Editor of Time, the Brain | The Curator of Time | The History of Time | Ripples in the Pond | A Holy Land or Ruins

Chapter 7_ Pain: The Medicine That Heals a Wounded Heart

Painkillers for emotional wounds | Between hope and despair | Social rejection vs. physical pain | Everyone suffers | Pain is a warning sign | The painkiller called love

Chapter 8_ Emotions: A Code for Reading Cultural Differences

Emotional Constellations | Factors That Determine Emotions | Happy Americans, Sad Russians | Drawing and Introducing Yourself | Same Expressions, Different Interpretations

Part 3: Cognitive Hacking: People Who Seek to Transcend Human Limits

Chapter 9: Virtual Reality: Existing Here and There Simultaneously

A Game, Not a Therapy | A Virtual Jeep Riding Through the Desert | The Moment the Magic Is Broken | I Became a Cow

Chapter 10: Augmented Reality: Overlaying the Cyber World on the Real World

Programmed Reality | The Preliminary Stages of a Brain Transplant | Why I Became a Cyborg | Big Brother vs. Little Brother | Augmented Reality Permeates Everyday Life | Survival of the Fittest in the Tech Age | Weird Futurism

Chapter 11: A New Sense: In Search of the Sixth Sense

Transplanting a New Sense | Grinders, the Body Hackers | Tactile or Synesthetic | The Technological Underclass | The Sixth Sense

Acknowledgements

Translator's Note

References

prolog

Part 1: The Five Senses: Five Pathways to the World

Chapter 1: Taste: A Journey to Discover the Sixth Taste

Attracting Tastes, Repulsive Tastes | Perception First, Language First | The Periodic Table of Tastes | The Taste of Brown | Tastes Created by Time | The Alchemy of Taste

Chapter 2_ Olfaction: Scents that evoke memories and emotions

Olfactory Therapy | The Proust Effect | The Correlation Between Smell and Emotion | The Topography of Smell | Olfactory and Alzheimer's | Linguistic Definitions, Cultural Associations, and Personal Memory | A Journey into the Past

Chapter 3: Vision: A World Without Light, and Beyond

A World of Reflection and Contrast | Perceiving Through Images | A Second Eye | Reading the World Through Electronic Language | Guinea Pigs, Not Patients

Chapter 4: Hearing: Electrical Signals That Draw Thoughts

The Thought-Reading Hat | From Ear to Brain | Auditory Imagery | Stimulus Reconstruction | The Age of Surveillance

Chapter 5: Touch: The Operating Room Without a Doctor

Replacing sight with touch | First-generation surgical robots | Surgery performed with thoughts, not hands | The brain, a black box

Part 2: Extrasensory Perception: The World Inside Your Head

Chapter 6_ Time: A Clock That Lasts 10,000 Years

The Editor of Time, the Brain | The Curator of Time | The History of Time | Ripples in the Pond | A Holy Land or Ruins

Chapter 7_ Pain: The Medicine That Heals a Wounded Heart

Painkillers for emotional wounds | Between hope and despair | Social rejection vs. physical pain | Everyone suffers | Pain is a warning sign | The painkiller called love

Chapter 8_ Emotions: A Code for Reading Cultural Differences

Emotional Constellations | Factors That Determine Emotions | Happy Americans, Sad Russians | Drawing and Introducing Yourself | Same Expressions, Different Interpretations

Part 3: Cognitive Hacking: People Who Seek to Transcend Human Limits

Chapter 9: Virtual Reality: Existing Here and There Simultaneously

A Game, Not a Therapy | A Virtual Jeep Riding Through the Desert | The Moment the Magic Is Broken | I Became a Cow

Chapter 10: Augmented Reality: Overlaying the Cyber World on the Real World

Programmed Reality | The Preliminary Stages of a Brain Transplant | Why I Became a Cyborg | Big Brother vs. Little Brother | Augmented Reality Permeates Everyday Life | Survival of the Fittest in the Tech Age | Weird Futurism

Chapter 11: A New Sense: In Search of the Sixth Sense

Transplanting a New Sense | Grinders, the Body Hackers | Tactile or Synesthetic | The Technological Underclass | The Sixth Sense

Acknowledgements

Translator's Note

References

Detailed image

Into the book

Lloyd was originally able to see, but gradually lost his vision due to retinitis pigmentosa.

Retinitis pigmentosa is a genetic disorder that destroys the light-sensing photoreceptor cells in the eye.

For 17 years, he lived virtually blind, only able to distinguish between day and night.

Then, in 2007, he applied for the Argus 2 clinical trial and became the seventh person in the United States to receive an artificial retina transplant and one of only 30 people in the world to receive an artificial retina transplant.

(…) Lloyd remembers the light.

I remember the color too.

I remember the text too.

It also remembers the shapes of objects and people.

Because he has this memory, he knows full well that the visual information transmitted through Argus is simpler than reality.

But that visual information is meaningful.

The fact that he uses it every day is proof of that.

He used a cane when going out, but indoors he relied on memory, touch, and argus to get around.

Reading legal documents and other tasks requires assistance from others and even electronic devices such as "talking watches."

However, he does not read Braille, does not use a guide dog, and uses a regular typewriter.

He sees the world like this every moment.

“The human brain has to process whatever information comes into it.

Sometimes we find meaning in the absurd.

“The brain is the most wonderful organ in the human body.”

Lloyd says.

- Chapter 3 [Vision]_ 116-120p

Buonomano, a neurophysiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, studies milliseconds to try to figure out how the brain, which has no time-measuring area, calculates time.

According to Buonomano, humans do not have a separate organ to perceive time.

Because unlike our eyes, which respond to photons, our tongue and nose to chemicals, our ears to vibrations, and our skin to pressure, time has no measurable physical properties.

“It is not so surprising that just as we have no sense organs to measure space, we also have no sense organs to measure time.

“Because both space and time are essential elements that make up dimension, they are everywhere,” he says.

(…)

So how do we perceive time?

The neural function of recording time is likely distributed throughout the brain.

We use several senses together to measure time.

Imagine a herd of wild horses running across the Texas plains.

You can tell the time by watching the horse approaching, that is, by watching its size increase as it gets closer.

You can also tell the time by placing your hand on the ground and feeling the vibrations.

Thanks to the Doppler effect (the distortion of frequency and wavelength depending on the relative speed of the wave source and the observer), you can even tell time by listening to the thump of horses passing by.

And finally, the brain edits time.

This is the most fascinating part of the recognition mechanism.

- Chapter 6 [Time]_ 219-221p

I became a cow.

I was in a beautiful pasture with a barn in the distance and vast green fields.

There was another cow in front of me.

The lab assistant explained that this cow was my avatar reflected in the mirror.

I was lying down with my helmet on, so it was hard to see myself transformed into a cow, so I showed it like this.

I let out an exclamation of “Wow!” without realizing it.

Because I loved the sight of myself transformed into a tiny brown and white calf.

“Welcome to Stanford Ranch.

You are a Shorthorn cow.

“They are raised for dairy and beef production.” After that, I continued to graze and drink water as the voice instructed.

And after some time, the voice was heard again.

“Now go to the fence where you were at the very beginning.

You've been here for about 200 days and have reached your goal weight.

Now it's time to go to the slaughterhouse."

It was unexpected.

When I heard the word 'slaughterhouse', sadness and fear came over me.

This sudden statement made me feel trapped and made me feel guilty and responsible towards Avatar So.

But the simulation continued.

“Now wait for the slaughterhouse truck.” The floor vibrates as the voice calls out, and the truck approaches.

I could hear tires screeching and the truck backing up.

As the world around me shakes violently, I feel genuine fear.

I shake my head from side to side to see where the truck is coming from.

What will happen when the truck comes? “Oh, no… you guys really…” I muttered in relief as the instructor took off my helmet.

- Chapter 9 [Virtual Reality]_ 346-348p

Retinitis pigmentosa is a genetic disorder that destroys the light-sensing photoreceptor cells in the eye.

For 17 years, he lived virtually blind, only able to distinguish between day and night.

Then, in 2007, he applied for the Argus 2 clinical trial and became the seventh person in the United States to receive an artificial retina transplant and one of only 30 people in the world to receive an artificial retina transplant.

(…) Lloyd remembers the light.

I remember the color too.

I remember the text too.

It also remembers the shapes of objects and people.

Because he has this memory, he knows full well that the visual information transmitted through Argus is simpler than reality.

But that visual information is meaningful.

The fact that he uses it every day is proof of that.

He used a cane when going out, but indoors he relied on memory, touch, and argus to get around.

Reading legal documents and other tasks requires assistance from others and even electronic devices such as "talking watches."

However, he does not read Braille, does not use a guide dog, and uses a regular typewriter.

He sees the world like this every moment.

“The human brain has to process whatever information comes into it.

Sometimes we find meaning in the absurd.

“The brain is the most wonderful organ in the human body.”

Lloyd says.

- Chapter 3 [Vision]_ 116-120p

Buonomano, a neurophysiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, studies milliseconds to try to figure out how the brain, which has no time-measuring area, calculates time.

According to Buonomano, humans do not have a separate organ to perceive time.

Because unlike our eyes, which respond to photons, our tongue and nose to chemicals, our ears to vibrations, and our skin to pressure, time has no measurable physical properties.

“It is not so surprising that just as we have no sense organs to measure space, we also have no sense organs to measure time.

“Because both space and time are essential elements that make up dimension, they are everywhere,” he says.

(…)

So how do we perceive time?

The neural function of recording time is likely distributed throughout the brain.

We use several senses together to measure time.

Imagine a herd of wild horses running across the Texas plains.

You can tell the time by watching the horse approaching, that is, by watching its size increase as it gets closer.

You can also tell the time by placing your hand on the ground and feeling the vibrations.

Thanks to the Doppler effect (the distortion of frequency and wavelength depending on the relative speed of the wave source and the observer), you can even tell time by listening to the thump of horses passing by.

And finally, the brain edits time.

This is the most fascinating part of the recognition mechanism.

- Chapter 6 [Time]_ 219-221p

I became a cow.

I was in a beautiful pasture with a barn in the distance and vast green fields.

There was another cow in front of me.

The lab assistant explained that this cow was my avatar reflected in the mirror.

I was lying down with my helmet on, so it was hard to see myself transformed into a cow, so I showed it like this.

I let out an exclamation of “Wow!” without realizing it.

Because I loved the sight of myself transformed into a tiny brown and white calf.

“Welcome to Stanford Ranch.

You are a Shorthorn cow.

“They are raised for dairy and beef production.” After that, I continued to graze and drink water as the voice instructed.

And after some time, the voice was heard again.

“Now go to the fence where you were at the very beginning.

You've been here for about 200 days and have reached your goal weight.

Now it's time to go to the slaughterhouse."

It was unexpected.

When I heard the word 'slaughterhouse', sadness and fear came over me.

This sudden statement made me feel trapped and made me feel guilty and responsible towards Avatar So.

But the simulation continued.

“Now wait for the slaughterhouse truck.” The floor vibrates as the voice calls out, and the truck approaches.

I could hear tires screeching and the truck backing up.

As the world around me shakes violently, I feel genuine fear.

I shake my head from side to side to see where the truck is coming from.

What will happen when the truck comes? “Oh, no… you guys really…” I muttered in relief as the instructor took off my helmet.

- Chapter 9 [Virtual Reality]_ 346-348p

--- From the text

Publisher's Review

Are all the sensations we feel real?

Or is it a fictitious image created by the brain?

Our brain is involved in all of the human senses.

For example, we think that touch is directly felt through our fingertips, skin, or body parts, but in reality, this is not the case.

Stimuli received from the outside are converted into electrical signals and transmitted to the brain, and the brain processes the electrical signals and tells us how we should feel.

That is 'awareness'.

This series of events from sensation to perception happens so quickly that we often forget about the organ called the brain.

But the tiny 1.4-kilogram brain inside our heads controls and manages all five senses: not only touch, but also taste, smell, hearing, and sight.

Therefore, the world we see through our brain can sometimes be identical to the real world, or it can be a completely different world.

In other words, the world that unfolds before us can be both ‘real’ and ‘appears to be real.’

So, by what principle does the brain receive external sensations and transmit them back to us?

The author of this book, Kara Platoni, is a journalist and author who has won numerous prestigious awards, including the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award for Young Science Journalists.

She was a lecturer at the University of California, Berkeley, and left school to write this book, traveling to the United States, Germany, England, and France for three years to gather relevant information.

She questioned what happens in the human brain during contact with the outside world, and whether, despite the brain's limited cognitive abilities, it is possible to enhance or alter our ability to perceive the world.

She met with a wide range of people, including neuroscientists, engineers, psychologists, geneticists, surgeons, transhumanists, futurists, ethicists, chefs, and perfumers, and gathered a vast amount of data, which she incorporated into this book.

A vivid glimpse into the forefront of cognitive science, exploring the limits of sense and perception!

Part 1 of this book, {The Five Senses: Five Ways to Encounter the World}, covers taste, smell, sight, hearing, and touch.

The five basic tastes currently recognized worldwide are sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami, also known as savory.

These basic tastes are tastes that we can clearly distinguish the moment we taste them, and at the same time, they are tastes that we can clearly express as 'what kind of taste'.

But we can taste more, even though we cannot express it in words.

Ultimately, we can see that taste is an object of recognition obtained through the brain's perception, and that recognition is concretized through outward expression.

To overcome this limitation of perception, some people explore the so-called 'sixth taste'.

The author visits natural science museums, university research labs, and San Francisco restaurants to show us the infinite possibilities of how our perception of taste can expand if we discover a language to describe new flavors.

The sense of smell is also closely connected to the brain's perception.

In a hospital in France, a study on scent and forgetting is underway with patients suffering from Alzheimer's disease.

Loss of the ability to distinguish smells is an early clinical sign of memory-related diseases, including Alzheimer's.

The brain is where memories are stored.

“I mechanically brought a spoonful of black tea with a piece of madeleine melted in it to my lips.

But the moment a sip of black tea mixed with a piece of cookie touched the roof of my mouth, I was startled and noticed that something special was happening inside my body.

A sweet joy, of unknown origin, seized me and isolated me.

(…) Then suddenly a memory came to mind.

It tasted like the pieces of madeleine that Aunt Léonie used to give me, dipped in black tea or barley tea, every Sunday morning when I went to say good morning to her in Combray.”

This is a passage from French novelist Marcel Proust's 'In Search of Lost Time'.

This phenomenon, also known as the 'Proust effect', is a representative example showing that the sense of smell is closely related to an individual's cultural background, experiences, and memories that have permeated their life.

Our sense of smell is greatly influenced by the cultural background in which each individual grew up, and it is one of the main factors in reviving long-forgotten memories.

The connection between scent and memory can be confirmed through various cases of treating Alzheimer's disease through aromatherapy.

We will also learn about how our brain receives and interprets visual stimuli through Lloyd, a blind man who is living a new life with a prosthetic retina device called Argus 2.

Hearing is the perception of sound waves in the air.

The brain converts these sound waves into electrical signals to understand the meaning of the sound.

Using this principle, Jack Gallant, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley, is researching ways to analyze the brain's electrical signals and convert them back into speech signals.

His research shows that if the sound waves flowing into the brain can be converted into language, it will be possible for our thoughts to be expressed in sound, words, and language.

It is now common to see machines in the operating room.

Nowadays, doctors on the other side of the world can operate on patients.

However, the problem that remains unresolved is whether the tactile sensation felt by the machine can be accurately conveyed to the doctor operating the machine.

A research team at Stanford University is seeking a solution to this problem through research on artificial arms using brain-machine interfaces.

If tactile responses and brain perception can be realized simultaneously through machines, machines will be used for surgeries on blood vessels, organs, and nerve organs that are difficult to reach with hands.

An intellectual journey to discover the source of extrasensory perception, which is edited within the brain!

Part 2 of this book, Extrasensory Perception: The World Inside Your Head, discusses various extrasensories that are perceived within the brain rather than sensations that can be felt physically.

For example, knowing time is a crucial clue to human behavior, understanding the world, predicting events, and understanding bodily sensations.

So what exactly is time, and how do we perceive it? It's still not clear how the brain perceives time.

Time is not something that can be perceived through hands, feet, or skin.

Time is a complex sense that we perceive through the integration of our various senses, such as seeing, hearing, and smelling the world around us.

We understand the passage of time through the movement of the sun, the sound of something approaching from afar, and the changing scents.

We get a glimpse into this complex and mysterious process of perception through the "10,000-Year Clock" being built by a group of futurists and engineers in Texas.

What about pain? Our brain perceives pain in the same area regardless of the type of pain.

The part of the brain that feels the pain of a broken bone is the same part that feels the pain of heartbreak and grief, argues UCLA psychologist Naomi Eisenberger.

So, can't painkillers that treat physical pain also treat mental pain? Professor Kipling, a social psychologist at Purdue University, explores this point through research on the brain's functions involved in pain.

Chensoba Dutton, a cultural psychologist at Georgetown University, is researching the hypothesis that culture influences our perception of emotions.

Our behavior is not innate.

Behavior is strongly influenced by emotions, and emotions accumulate within us in various ways depending on the cultural background in which each person grew up.

For example, it has been found that while everyone desires happiness, the nature of this desire varies somewhat across cultures.

East Asians value a peaceful and quiet happiness, while Americans value the happiness that comes from thrilling excitement.

Even Russians value negative emotions like sadness more than joy.

This diversity of emotions ultimately governs how we interpret the world around us, and at the heart of it all is the brain.

How would human perception change if the mechanisms through which we perceive sensations changed?

People who envision a future where science and technology coexist beyond the limits of the senses!

The final part, Part 3, {Cognitive Hacking: People Trying to Overcome Human Limits}, showcases various attempts to expand the realm of the body's senses through science and technology.

Virtual reality is a very powerful way to enter an imaginary landscape.

Current virtual reality systems have become so precise that subjects perceive them almost identically to the real world.

Stanford University cognitive psychologist Dr. Jeremy argues that virtual reality is an essential tool for creating a better world.

This is because the emotions and actions obtained in virtual reality can bring about powerful changes that can carry over to the real world.

In fact, virtual reality technology is actively being used to treat psychological disorders such as phobias and post-traumatic stress disorder in soldiers.

Augmented reality technology, which allows us to perceive the real and virtual worlds simultaneously, is expanding its scope and revolutionizing our very concept of senses.

Glasses equipped with augmented reality allow you to see in the dark and see behind you without turning your head.

It can read digital signals, record everything we see, and even send the sensation of a hug to a lover far away.

Documentary filmmaker Rob Spencer lost the sight in one eye completely, had it removed, and had a device implanted in its place that allows him to wear a variety of prosthetic eyes.

He shoots movies with this device called an iCam.

It is even possible to receive information wirelessly from a distance, or vice versa.

The book concludes with stories of people who question the very function of the body's direct senses and seek to overcome their limitations.

In reality, the world that humans can literally sense—see, hear, taste, and smell—is extremely small and narrow.

Humans cannot hear ultrasound like bats or dolphins, and cannot see ultraviolet light like bees.

They can't detect electricity like sharks or rays.

However, the biohackers and transhumanists who appear in the last chapter are attempting to overcome the innate limitations of human senses by implanting magnetic or radio frequency recognition chips in the body.

This is not a sensation detected through a new area of the brain, but rather the ability to perceive stimuli that were not previously perceived, and is called the 'sixth sense'.

Through these, we can glimpse the vision of how far humanity, supported by science and technology, can evolve.

Science and technology are expanding at a pace and scale we could never have imagined before.

As we face the era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, humanity is moving quickly to coexist harmoniously with technology.

This book talks about the current state of humanity surrounding the senses.

At the same time, it depicts a future humanity equipped with new senses.

The Anthropocene, which began with agriculture around 8,000 BC, is now entering a new era of coexistence with artificial intelligence.

Perhaps the future we are about to experience is a world we have never even imagined, a world more unrealistic than anything we have seen in science fiction novels or movies.

But this world is undoubtedly the future that will unfold before us someday.

This is because humanity's endless curiosity and spirit of adventure have consistently brought to fruition what they have imagined and dreamed of.

The most fundamental and human desire for humanity to evolve into a better being is this desire that has sustained humanity to this day and will enable us to create a new history for humanity in the future.

Through this book, "The Future of Sense," we will willingly stand together at the starting line toward that future.

Or is it a fictitious image created by the brain?

Our brain is involved in all of the human senses.

For example, we think that touch is directly felt through our fingertips, skin, or body parts, but in reality, this is not the case.

Stimuli received from the outside are converted into electrical signals and transmitted to the brain, and the brain processes the electrical signals and tells us how we should feel.

That is 'awareness'.

This series of events from sensation to perception happens so quickly that we often forget about the organ called the brain.

But the tiny 1.4-kilogram brain inside our heads controls and manages all five senses: not only touch, but also taste, smell, hearing, and sight.

Therefore, the world we see through our brain can sometimes be identical to the real world, or it can be a completely different world.

In other words, the world that unfolds before us can be both ‘real’ and ‘appears to be real.’

So, by what principle does the brain receive external sensations and transmit them back to us?

The author of this book, Kara Platoni, is a journalist and author who has won numerous prestigious awards, including the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award for Young Science Journalists.

She was a lecturer at the University of California, Berkeley, and left school to write this book, traveling to the United States, Germany, England, and France for three years to gather relevant information.

She questioned what happens in the human brain during contact with the outside world, and whether, despite the brain's limited cognitive abilities, it is possible to enhance or alter our ability to perceive the world.

She met with a wide range of people, including neuroscientists, engineers, psychologists, geneticists, surgeons, transhumanists, futurists, ethicists, chefs, and perfumers, and gathered a vast amount of data, which she incorporated into this book.

A vivid glimpse into the forefront of cognitive science, exploring the limits of sense and perception!

Part 1 of this book, {The Five Senses: Five Ways to Encounter the World}, covers taste, smell, sight, hearing, and touch.

The five basic tastes currently recognized worldwide are sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami, also known as savory.

These basic tastes are tastes that we can clearly distinguish the moment we taste them, and at the same time, they are tastes that we can clearly express as 'what kind of taste'.

But we can taste more, even though we cannot express it in words.

Ultimately, we can see that taste is an object of recognition obtained through the brain's perception, and that recognition is concretized through outward expression.

To overcome this limitation of perception, some people explore the so-called 'sixth taste'.

The author visits natural science museums, university research labs, and San Francisco restaurants to show us the infinite possibilities of how our perception of taste can expand if we discover a language to describe new flavors.

The sense of smell is also closely connected to the brain's perception.

In a hospital in France, a study on scent and forgetting is underway with patients suffering from Alzheimer's disease.

Loss of the ability to distinguish smells is an early clinical sign of memory-related diseases, including Alzheimer's.

The brain is where memories are stored.

“I mechanically brought a spoonful of black tea with a piece of madeleine melted in it to my lips.

But the moment a sip of black tea mixed with a piece of cookie touched the roof of my mouth, I was startled and noticed that something special was happening inside my body.

A sweet joy, of unknown origin, seized me and isolated me.

(…) Then suddenly a memory came to mind.

It tasted like the pieces of madeleine that Aunt Léonie used to give me, dipped in black tea or barley tea, every Sunday morning when I went to say good morning to her in Combray.”

This is a passage from French novelist Marcel Proust's 'In Search of Lost Time'.

This phenomenon, also known as the 'Proust effect', is a representative example showing that the sense of smell is closely related to an individual's cultural background, experiences, and memories that have permeated their life.

Our sense of smell is greatly influenced by the cultural background in which each individual grew up, and it is one of the main factors in reviving long-forgotten memories.

The connection between scent and memory can be confirmed through various cases of treating Alzheimer's disease through aromatherapy.

We will also learn about how our brain receives and interprets visual stimuli through Lloyd, a blind man who is living a new life with a prosthetic retina device called Argus 2.

Hearing is the perception of sound waves in the air.

The brain converts these sound waves into electrical signals to understand the meaning of the sound.

Using this principle, Jack Gallant, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley, is researching ways to analyze the brain's electrical signals and convert them back into speech signals.

His research shows that if the sound waves flowing into the brain can be converted into language, it will be possible for our thoughts to be expressed in sound, words, and language.

It is now common to see machines in the operating room.

Nowadays, doctors on the other side of the world can operate on patients.

However, the problem that remains unresolved is whether the tactile sensation felt by the machine can be accurately conveyed to the doctor operating the machine.

A research team at Stanford University is seeking a solution to this problem through research on artificial arms using brain-machine interfaces.

If tactile responses and brain perception can be realized simultaneously through machines, machines will be used for surgeries on blood vessels, organs, and nerve organs that are difficult to reach with hands.

An intellectual journey to discover the source of extrasensory perception, which is edited within the brain!

Part 2 of this book, Extrasensory Perception: The World Inside Your Head, discusses various extrasensories that are perceived within the brain rather than sensations that can be felt physically.

For example, knowing time is a crucial clue to human behavior, understanding the world, predicting events, and understanding bodily sensations.

So what exactly is time, and how do we perceive it? It's still not clear how the brain perceives time.

Time is not something that can be perceived through hands, feet, or skin.

Time is a complex sense that we perceive through the integration of our various senses, such as seeing, hearing, and smelling the world around us.

We understand the passage of time through the movement of the sun, the sound of something approaching from afar, and the changing scents.

We get a glimpse into this complex and mysterious process of perception through the "10,000-Year Clock" being built by a group of futurists and engineers in Texas.

What about pain? Our brain perceives pain in the same area regardless of the type of pain.

The part of the brain that feels the pain of a broken bone is the same part that feels the pain of heartbreak and grief, argues UCLA psychologist Naomi Eisenberger.

So, can't painkillers that treat physical pain also treat mental pain? Professor Kipling, a social psychologist at Purdue University, explores this point through research on the brain's functions involved in pain.

Chensoba Dutton, a cultural psychologist at Georgetown University, is researching the hypothesis that culture influences our perception of emotions.

Our behavior is not innate.

Behavior is strongly influenced by emotions, and emotions accumulate within us in various ways depending on the cultural background in which each person grew up.

For example, it has been found that while everyone desires happiness, the nature of this desire varies somewhat across cultures.

East Asians value a peaceful and quiet happiness, while Americans value the happiness that comes from thrilling excitement.

Even Russians value negative emotions like sadness more than joy.

This diversity of emotions ultimately governs how we interpret the world around us, and at the heart of it all is the brain.

How would human perception change if the mechanisms through which we perceive sensations changed?

People who envision a future where science and technology coexist beyond the limits of the senses!

The final part, Part 3, {Cognitive Hacking: People Trying to Overcome Human Limits}, showcases various attempts to expand the realm of the body's senses through science and technology.

Virtual reality is a very powerful way to enter an imaginary landscape.

Current virtual reality systems have become so precise that subjects perceive them almost identically to the real world.

Stanford University cognitive psychologist Dr. Jeremy argues that virtual reality is an essential tool for creating a better world.

This is because the emotions and actions obtained in virtual reality can bring about powerful changes that can carry over to the real world.

In fact, virtual reality technology is actively being used to treat psychological disorders such as phobias and post-traumatic stress disorder in soldiers.

Augmented reality technology, which allows us to perceive the real and virtual worlds simultaneously, is expanding its scope and revolutionizing our very concept of senses.

Glasses equipped with augmented reality allow you to see in the dark and see behind you without turning your head.

It can read digital signals, record everything we see, and even send the sensation of a hug to a lover far away.

Documentary filmmaker Rob Spencer lost the sight in one eye completely, had it removed, and had a device implanted in its place that allows him to wear a variety of prosthetic eyes.

He shoots movies with this device called an iCam.

It is even possible to receive information wirelessly from a distance, or vice versa.

The book concludes with stories of people who question the very function of the body's direct senses and seek to overcome their limitations.

In reality, the world that humans can literally sense—see, hear, taste, and smell—is extremely small and narrow.

Humans cannot hear ultrasound like bats or dolphins, and cannot see ultraviolet light like bees.

They can't detect electricity like sharks or rays.

However, the biohackers and transhumanists who appear in the last chapter are attempting to overcome the innate limitations of human senses by implanting magnetic or radio frequency recognition chips in the body.

This is not a sensation detected through a new area of the brain, but rather the ability to perceive stimuli that were not previously perceived, and is called the 'sixth sense'.

Through these, we can glimpse the vision of how far humanity, supported by science and technology, can evolve.

Science and technology are expanding at a pace and scale we could never have imagined before.

As we face the era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, humanity is moving quickly to coexist harmoniously with technology.

This book talks about the current state of humanity surrounding the senses.

At the same time, it depicts a future humanity equipped with new senses.

The Anthropocene, which began with agriculture around 8,000 BC, is now entering a new era of coexistence with artificial intelligence.

Perhaps the future we are about to experience is a world we have never even imagined, a world more unrealistic than anything we have seen in science fiction novels or movies.

But this world is undoubtedly the future that will unfold before us someday.

This is because humanity's endless curiosity and spirit of adventure have consistently brought to fruition what they have imagined and dreamed of.

The most fundamental and human desire for humanity to evolve into a better being is this desire that has sustained humanity to this day and will enable us to create a new history for humanity in the future.

Through this book, "The Future of Sense," we will willingly stand together at the starting line toward that future.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: August 1, 2017

- Page count, weight, size: 460 pages | 784g | 152*225*30mm

- ISBN13: 9788965962274

- ISBN10: 8965962277

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)