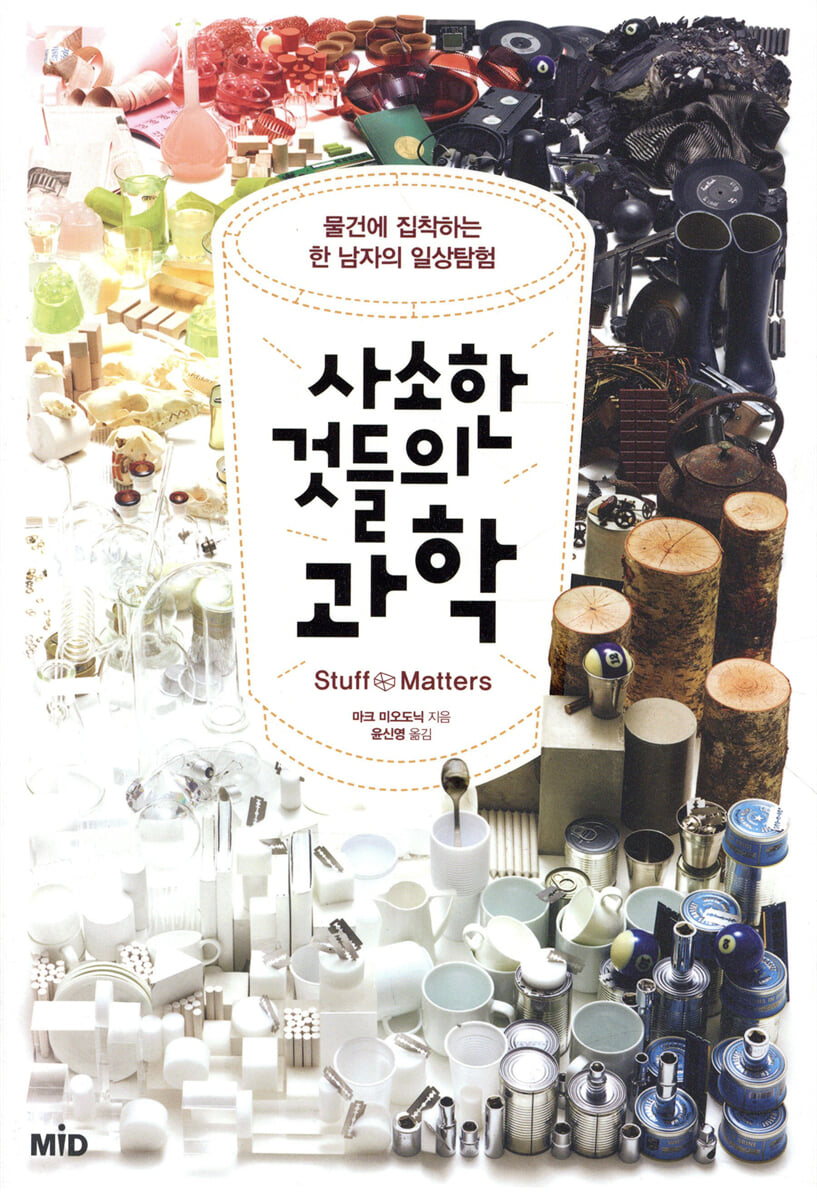

The Science of Little Things

|

Description

Book Introduction

“The Next Bill Bryson!”_Booklist The emergence of an extraordinary science author! There is a man born in England. As a child, this man was threatened by a stranger at a train station and had his back cut with a razor blade. The young boy was amazed by the power of a razor blade the size of a postage stamp, curious about the iron it was made of, and amazed by the fact that iron is everywhere in the world, asking himself countless questions. “You put iron in your mouth (spoon), cut your hair with iron (scissors), and ride iron (car). How does one simple ingredient do so many things? “Why do razors cut and paperclips bend?” “Why does chocolate taste good?” The man then spends most of his time obsessed with the material. As he grew up, he majored in materials science and worked as a materials scientist and engineer at some of the world's most advanced research institutes, demonstrating a natural talent for looking inside things and imagining their structures and properties. Although it is called 'talent', it is actually closer to 'an interest bordering on obsession'. (We may take obsession or interest in a less than pleasant way. But for scientists, it's not such a bad or unsuitable word. Because there is a world that can only be explored persistently if you have obsession and interest. And the material science that this man studies is a world that requires just that kind of persistence.) And this man, with his overflowing passion, love, and tenacity for the material, writes a book that fully utilizes the knowledge he has accumulated, guiding us into the world of unfamiliar yet fresh ingredients. ▶ Original book 『Stuff Matters』 cover making video |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommendation

The pleasure of meeting a cool new science writer

prolog

Myodonic in the Strange Material World

Chapter 1: Indomitable: Steel

Chapter 2: Warm: Paper

Chapter 3: Basics: Concrete

Chapter 4: Delicious: Chocolate

Chapter 5: Amazing: Foam

Chapter 6: Imaginative: Plastic

Chapter 7: Invisible: Glass

Chapter 8: Unbreakable: Graphite

Chapter 9: Sophisticated: Porcelain

Chapter 10: Immortality: Biomaterial Implants

Epilogue

We are our material

The pleasure of meeting a cool new science writer

prolog

Myodonic in the Strange Material World

Chapter 1: Indomitable: Steel

Chapter 2: Warm: Paper

Chapter 3: Basics: Concrete

Chapter 4: Delicious: Chocolate

Chapter 5: Amazing: Foam

Chapter 6: Imaginative: Plastic

Chapter 7: Invisible: Glass

Chapter 8: Unbreakable: Graphite

Chapter 9: Sophisticated: Porcelain

Chapter 10: Immortality: Biomaterial Implants

Epilogue

We are our material

Detailed image

Into the book

The fundamental importance of materials is evident in the names we use to classify the stages of civilization.

The Stone Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age signify that mankind was reborn as a new being through new materials.

(syncopation)

How many people can tell the difference between aluminum and steel? Wood is clearly different, but how many can explain why? Plastic is confusing.

Who knows the difference between polyethylene and polypropylene? But what's more important might be what comes next.

Who the hell cares?

I care.

So I want to explain to you why.

---From the "Prologue"

Brearley continued his quest to create the world's first stainless steel knife.

But soon he ran into a problem.

The new metal was not hard enough to make a sharp blade, and it quickly became dull, becoming a 'knife that couldn't cut'.

Because of its lack of hardness, Brearley quickly dismissed stainless steel as an unsuitable alloy for use in guns.

But stainless steel could be shaped into complex shapes, and a century later it became one of the most influential pieces of British sculpture.

There is one of these sculptures in every home now.

It's the kitchen sink.

---From "Indomitable: Steel"

To prevent counterfeiting, banknotes have several clever devices hidden inside them.

First of all, unlike other papers, it is not made from tree cellulose but from cotton.

Cotton cellulose makes the banknotes stronger and less likely to break down when exposed to rain or washed in the washing machine.

Cotton also changed the distinctive sound that paper makes, making the rustling sound one of the most recognizable characteristics of banknotes.

The fact that it is made of cotton is also the most powerful means of preventing counterfeiting.

Because it is difficult to make counterfeit money with paper made from trees.

---From "Midaun: Paper"

The structure of graphite is very different from that of diamond.

Carbon atoms are connected in a hexagonal shape to form a plane.

Each plane is a very strong and stable structure, and the bonds between carbon atoms are stronger than those in diamond.

This is surprising, because graphite is so soft that it is used as a lubricant and pencil lead.

(syncopation)

For those unfamiliar with the term, graphene is the thinnest, strongest, and hardest material in the world.

It conducts heat faster, conducts more electricity faster, and has less resistance than any other material known.

It also allows for Klein tunneling, a strange quantum effect in which electrons in a material pass through a wall as if it were never there.

All these properties mean that graphene has the potential to become the electronic device that replaces silicon chips at the heart of computing and communications.

The Stone Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age signify that mankind was reborn as a new being through new materials.

(syncopation)

How many people can tell the difference between aluminum and steel? Wood is clearly different, but how many can explain why? Plastic is confusing.

Who knows the difference between polyethylene and polypropylene? But what's more important might be what comes next.

Who the hell cares?

I care.

So I want to explain to you why.

---From the "Prologue"

Brearley continued his quest to create the world's first stainless steel knife.

But soon he ran into a problem.

The new metal was not hard enough to make a sharp blade, and it quickly became dull, becoming a 'knife that couldn't cut'.

Because of its lack of hardness, Brearley quickly dismissed stainless steel as an unsuitable alloy for use in guns.

But stainless steel could be shaped into complex shapes, and a century later it became one of the most influential pieces of British sculpture.

There is one of these sculptures in every home now.

It's the kitchen sink.

---From "Indomitable: Steel"

To prevent counterfeiting, banknotes have several clever devices hidden inside them.

First of all, unlike other papers, it is not made from tree cellulose but from cotton.

Cotton cellulose makes the banknotes stronger and less likely to break down when exposed to rain or washed in the washing machine.

Cotton also changed the distinctive sound that paper makes, making the rustling sound one of the most recognizable characteristics of banknotes.

The fact that it is made of cotton is also the most powerful means of preventing counterfeiting.

Because it is difficult to make counterfeit money with paper made from trees.

---From "Midaun: Paper"

The structure of graphite is very different from that of diamond.

Carbon atoms are connected in a hexagonal shape to form a plane.

Each plane is a very strong and stable structure, and the bonds between carbon atoms are stronger than those in diamond.

This is surprising, because graphite is so soft that it is used as a lubricant and pencil lead.

(syncopation)

For those unfamiliar with the term, graphene is the thinnest, strongest, and hardest material in the world.

It conducts heat faster, conducts more electricity faster, and has less resistance than any other material known.

It also allows for Klein tunneling, a strange quantum effect in which electrons in a material pass through a wall as if it were never there.

All these properties mean that graphene has the potential to become the electronic device that replaces silicon chips at the heart of computing and communications.

---From "graphite"

Publisher's Review

After reading this book, you will never look at a pencil, a teacup, or even a razor blade the same again.

(You'll Never Look at a Pencil, Teacup, or Razor Blade the Same Way.)

- by Bill Gates, July 23, 2015

People have attachments in one way or another.

From the ridiculous to the serious.

I think it's one of the most beautiful things about humanity that we can get lost in something so diverse, from playing bridge (which I'm obsessed with) to scanning the night sky for new stars.

However, just because one person is fascinated by something doesn't mean it will necessarily be an interesting read for others who haven't been fascinated by the same thing.

In [Stuff Matters], Mark Miodonik's personal and professional passions encompass basic materials we take for granted—paper, glass, concrete, steel—as well as super materials that could change the world in the next decade.

I'm pleased to say that Myodonic is a witty and clever writer with a tremendous talent for sharing his love of these materials.

As a result, [Stuff Matters] is a fun and enjoyable read.

My favorite historian, Vaclav Smil, also wrote a wonderful book on the subject, but it's completely different from this one.

Smil doesn't romance the subject, focusing on facts and figures.

In the case of Myodonic, it is the polar opposite of Smil, with a lot of romance and not many numbers.

Myodonic is an Oxford-educated materials scientist who has worked in some of the world's leading research institutes and has shown a love of materials in bizarre ways.

In the 80s, when he was a high school student, he was the victim of a random crime on the London Underground.

Listening to his story, he says that even though his back was cut more than 10cm, he didn't panic and was obsessed with the criminal's steel razor blade.

"This tiny piece of steel, the size of a postage stamp, can effortlessly penetrate five layers of clothing, past the epidermis and into the dermis." "That's where my love affair with materials began."

Most of us have the luxury of never being attacked by a razor blade or thinking deeply about steel.

But as Myodonic explains so well, steel is quite attractive.

The biggest advantage is that although it is cast from cast iron, unlike cast iron, it does not crack or break when subjected to tension.

Steel has been crafted by skilled blacksmiths since ancient Roman times, but it wasn't until the mid-19th century, when processes for producing steel cheaply and on a large scale were invented, that it became central to our lives, from appliances and transportation to our homes.

The next century is likely to see even greater innovations in materials.

Near where I live is the world's longest pontoon bridge - the Evergreen Point Bridge, which connects Seattle to the neighboring city of Bellevue - and like many large modern structures, it is made of reinforced concrete.

This bridge was built over 50 years ago and is now nearing the end of its lifespan.

(You can see the construction site of a new bridge to replace this one from our yard.) According to MioDonic's claim, future bridges could be built with "self-healing concrete," which could save billions of dollars in repair and replacement costs.

Self-healing concrete is a really exciting area of materials innovation.

Scientists have discovered incredibly resilient bacteria in a volcanic lake with sulfur concentrations high enough to burn human skin.

These bacteria can remain dormant in rocks for decades.

When these bacteria are embedded in concrete along with their starch food, cracks develop in the concrete and water begins to seep in.

Then the bacteria come back to life, find the starch, start replicating themselves and releasing minerals to fill the cracks.

I especially liked the chapter on carbon ("unbreakable"), which gives useful information.

This chapter provides insight into how a single atom plays a pervasive role in human life, past, present, and future.

Diamond, one of the many forms in which the element carbon manifests itself, has played a leading role in love and war for thousands of years.

Coal was the driving force behind our industrial age and has had a significant impact on the chemistry of our atmosphere.

Carbon fiber composites, made by bonding graphite fibers to sheets of epoxy adhesive, are transforming major industries, from sports to aerospace to automotive.

I recently heard about a carbon fiber bus purchased by the city of Seattle that is said to be much lighter, stronger, cleaner, and safer than traditional steel buses, and will save a lot of fuel.

Then there are even more experimental forms of carbon, such as graphene, which is a single, one-atom-thick layer of graphite, or carbon nanotubes, which are rolled up into a ball.

Graphene is the thinnest and strongest material known to mankind—200 times stronger than steel, yet thinner than a sheet of paper.

Also, it conducts electricity the best.

(100 times stronger than copper) So, one day it will replace silicon chips and usher in a new era in computing and communications.

Yes, that's right.

Materials are important!

In the political arena, where politics is a battleground, voters sometimes give more weight to candidates they'd rather have a beer with than to qualified candidates.

A Myodonic is someone who anyone would want to have a beer with, and who is quite qualified.

I think I'll be interested in reading whatever book he writes next.

Your perspective on the world will change!

A science book that offers more fun than you can imagine and unique knowledge.

The author selected 10 ordinary ingredients that we often overlook in our daily lives.

The way the materials are selected is also unique.

Materials such as iron, paper, chocolate, glass, plastic, graphite, porcelain, and concrete were all selected from an ordinary photograph of the artist's daily life.

The author tells ten stories about each of the ten materials, going through the materials of the familiar objects in the photos one by one and telling the story 'inside' them.

The stories all begin with a story of one's own experience and unfold in an interesting way, with variations depending on the material.

For example, when guiding readers into the world of paper, he shows them his favorite letters, photos, train tickets, envelopes, bags, and other small items, introducing the characteristics and charm of the materials along with memories, making it cute and fun, like looking at an author's diary.

When entering the world of plastic, you can enjoy the fun of reading it as if you were drawing a short film, as it is structured in a short comedy format.

Also, after this delightful journey of experiencing various fun and immersing yourself in the world of materials, you suddenly feel a different emotion when you look at the world before you.

As if we were wearing different glasses to see the world, and although we may not be able to 'see inside things and imagine their structures and properties' like the author, we too will find bicycles parked on the side of the road, overpasses, skyscrapers, steel pillars supporting the roofs of subway entrances, and transparent elevators strangely familiar, or at the same time, strangely unfamiliar.

In short, we experience the world looking different as we come to know it.

Perhaps this experience is the greatest pleasure we can derive from reading an exciting and informative science book.

A young scientist with a unique personality

A fascinating feast of science!

In each chapter, the author does not simply introduce different materials or present scientific knowledge.

What he considers important is the perspective from which he looks at the material.

Depending on the nature of the material, some take a historical perspective, while others take a more scientific one.

In some cases it also emphasizes the cultural aspects of the material, and in other cases it emphasizes its remarkable technical capabilities.

Of course, there are cases where a single material requires both of these approaches at once.

The author believes that 'there is more to materials than science.'

Although materials themselves have meaning, all materials are ultimately made into something and appear to us.

So people who create things—designers, artists, chefs, engineers, furniture makers, jewelers, surgeons—all have different understandings of the materials they work with, in practical, emotional, and sensory terms.

The author is keenly aware of these points and captures this diversity of knowledge about materials.

This can also be said to be the power of the author, which is possible for a scientist with excellent sense and passion.

Through this book, readers will enjoy a captivating scientific journey that stimulates their intellectual curiosity, guided by the stylish and lively guidance of a young scientist who continues to delve deeply into all the materials of the world.

(You'll Never Look at a Pencil, Teacup, or Razor Blade the Same Way.)

- by Bill Gates, July 23, 2015

People have attachments in one way or another.

From the ridiculous to the serious.

I think it's one of the most beautiful things about humanity that we can get lost in something so diverse, from playing bridge (which I'm obsessed with) to scanning the night sky for new stars.

However, just because one person is fascinated by something doesn't mean it will necessarily be an interesting read for others who haven't been fascinated by the same thing.

In [Stuff Matters], Mark Miodonik's personal and professional passions encompass basic materials we take for granted—paper, glass, concrete, steel—as well as super materials that could change the world in the next decade.

I'm pleased to say that Myodonic is a witty and clever writer with a tremendous talent for sharing his love of these materials.

As a result, [Stuff Matters] is a fun and enjoyable read.

My favorite historian, Vaclav Smil, also wrote a wonderful book on the subject, but it's completely different from this one.

Smil doesn't romance the subject, focusing on facts and figures.

In the case of Myodonic, it is the polar opposite of Smil, with a lot of romance and not many numbers.

Myodonic is an Oxford-educated materials scientist who has worked in some of the world's leading research institutes and has shown a love of materials in bizarre ways.

In the 80s, when he was a high school student, he was the victim of a random crime on the London Underground.

Listening to his story, he says that even though his back was cut more than 10cm, he didn't panic and was obsessed with the criminal's steel razor blade.

"This tiny piece of steel, the size of a postage stamp, can effortlessly penetrate five layers of clothing, past the epidermis and into the dermis." "That's where my love affair with materials began."

Most of us have the luxury of never being attacked by a razor blade or thinking deeply about steel.

But as Myodonic explains so well, steel is quite attractive.

The biggest advantage is that although it is cast from cast iron, unlike cast iron, it does not crack or break when subjected to tension.

Steel has been crafted by skilled blacksmiths since ancient Roman times, but it wasn't until the mid-19th century, when processes for producing steel cheaply and on a large scale were invented, that it became central to our lives, from appliances and transportation to our homes.

The next century is likely to see even greater innovations in materials.

Near where I live is the world's longest pontoon bridge - the Evergreen Point Bridge, which connects Seattle to the neighboring city of Bellevue - and like many large modern structures, it is made of reinforced concrete.

This bridge was built over 50 years ago and is now nearing the end of its lifespan.

(You can see the construction site of a new bridge to replace this one from our yard.) According to MioDonic's claim, future bridges could be built with "self-healing concrete," which could save billions of dollars in repair and replacement costs.

Self-healing concrete is a really exciting area of materials innovation.

Scientists have discovered incredibly resilient bacteria in a volcanic lake with sulfur concentrations high enough to burn human skin.

These bacteria can remain dormant in rocks for decades.

When these bacteria are embedded in concrete along with their starch food, cracks develop in the concrete and water begins to seep in.

Then the bacteria come back to life, find the starch, start replicating themselves and releasing minerals to fill the cracks.

I especially liked the chapter on carbon ("unbreakable"), which gives useful information.

This chapter provides insight into how a single atom plays a pervasive role in human life, past, present, and future.

Diamond, one of the many forms in which the element carbon manifests itself, has played a leading role in love and war for thousands of years.

Coal was the driving force behind our industrial age and has had a significant impact on the chemistry of our atmosphere.

Carbon fiber composites, made by bonding graphite fibers to sheets of epoxy adhesive, are transforming major industries, from sports to aerospace to automotive.

I recently heard about a carbon fiber bus purchased by the city of Seattle that is said to be much lighter, stronger, cleaner, and safer than traditional steel buses, and will save a lot of fuel.

Then there are even more experimental forms of carbon, such as graphene, which is a single, one-atom-thick layer of graphite, or carbon nanotubes, which are rolled up into a ball.

Graphene is the thinnest and strongest material known to mankind—200 times stronger than steel, yet thinner than a sheet of paper.

Also, it conducts electricity the best.

(100 times stronger than copper) So, one day it will replace silicon chips and usher in a new era in computing and communications.

Yes, that's right.

Materials are important!

In the political arena, where politics is a battleground, voters sometimes give more weight to candidates they'd rather have a beer with than to qualified candidates.

A Myodonic is someone who anyone would want to have a beer with, and who is quite qualified.

I think I'll be interested in reading whatever book he writes next.

Your perspective on the world will change!

A science book that offers more fun than you can imagine and unique knowledge.

The author selected 10 ordinary ingredients that we often overlook in our daily lives.

The way the materials are selected is also unique.

Materials such as iron, paper, chocolate, glass, plastic, graphite, porcelain, and concrete were all selected from an ordinary photograph of the artist's daily life.

The author tells ten stories about each of the ten materials, going through the materials of the familiar objects in the photos one by one and telling the story 'inside' them.

The stories all begin with a story of one's own experience and unfold in an interesting way, with variations depending on the material.

For example, when guiding readers into the world of paper, he shows them his favorite letters, photos, train tickets, envelopes, bags, and other small items, introducing the characteristics and charm of the materials along with memories, making it cute and fun, like looking at an author's diary.

When entering the world of plastic, you can enjoy the fun of reading it as if you were drawing a short film, as it is structured in a short comedy format.

Also, after this delightful journey of experiencing various fun and immersing yourself in the world of materials, you suddenly feel a different emotion when you look at the world before you.

As if we were wearing different glasses to see the world, and although we may not be able to 'see inside things and imagine their structures and properties' like the author, we too will find bicycles parked on the side of the road, overpasses, skyscrapers, steel pillars supporting the roofs of subway entrances, and transparent elevators strangely familiar, or at the same time, strangely unfamiliar.

In short, we experience the world looking different as we come to know it.

Perhaps this experience is the greatest pleasure we can derive from reading an exciting and informative science book.

A young scientist with a unique personality

A fascinating feast of science!

In each chapter, the author does not simply introduce different materials or present scientific knowledge.

What he considers important is the perspective from which he looks at the material.

Depending on the nature of the material, some take a historical perspective, while others take a more scientific one.

In some cases it also emphasizes the cultural aspects of the material, and in other cases it emphasizes its remarkable technical capabilities.

Of course, there are cases where a single material requires both of these approaches at once.

The author believes that 'there is more to materials than science.'

Although materials themselves have meaning, all materials are ultimately made into something and appear to us.

So people who create things—designers, artists, chefs, engineers, furniture makers, jewelers, surgeons—all have different understandings of the materials they work with, in practical, emotional, and sensory terms.

The author is keenly aware of these points and captures this diversity of knowledge about materials.

This can also be said to be the power of the author, which is possible for a scientist with excellent sense and passion.

Through this book, readers will enjoy a captivating scientific journey that stimulates their intellectual curiosity, guided by the stylish and lively guidance of a young scientist who continues to delve deeply into all the materials of the world.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: April 1, 2016

- Page count, weight, size: 328 pages | 485g | 153*224*24mm

- ISBN13: 9791185104652

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)