Philosophy vs. Practice

|

Description

Book Introduction

- A word from MD

-

How Philosophy Changes the WorldKang Shin-ju returned after four years.

This time it is 19th century European political economy.

At a time when the fervor for change was boiling, there was the Paris Commune and Marx.

This book, the first in the series 'Kang Shin-ju's Philosophy of History and Politics', explores the true nature and current relevance of Marx's thought along with the Paris Commune.

June 16, 2020. Humanities PD Son Min-gyu

Philosopher Kang Shin-joo, who is releasing a new work after four years, confronts the history of oppressive systems.

By stripping away the essence of the oppressive system that has forced oppression and exploitation, it revives those who resisted it and those who fought against the oppressive system as masters of life and love.

This is a project to include the five volumes of 'Lectures on the Philosophy of History and Political Philosophy of Kang Shin-ju' about enlightened people, free people, and people who lived as masters.

The first volume, entitled Philosophy vs. Practice, consists of four chapters on the philosophy of history and four chapters on political philosophy.

First, the four chapters on the philosophy of history are devoted to vividly restoring the grandeur and immense scale of the Paris Commune and the concentration camps.

Explains what exactly happened within the Paris Commune and the concentration camps, and why the Paris Commune and the concentration camps still serve as practical reference points for our lives.

To more emotionally and effectively portray the spirit of free community that the Paris Commune and the Commune fostered, we cast Rimbaud, a poet from the Paris Commune, and Shin Dong-yup, a poet from the Commune.

In this way, the philosophy of history is divided into four chapters.

There are chapters dealing with the Paris Commune, chapters dealing with Rimbaud, chapters dealing with the concentration camp, and chapters dealing with Shin Dong-yup.

By stripping away the essence of the oppressive system that has forced oppression and exploitation, it revives those who resisted it and those who fought against the oppressive system as masters of life and love.

This is a project to include the five volumes of 'Lectures on the Philosophy of History and Political Philosophy of Kang Shin-ju' about enlightened people, free people, and people who lived as masters.

The first volume, entitled Philosophy vs. Practice, consists of four chapters on the philosophy of history and four chapters on political philosophy.

First, the four chapters on the philosophy of history are devoted to vividly restoring the grandeur and immense scale of the Paris Commune and the concentration camps.

Explains what exactly happened within the Paris Commune and the concentration camps, and why the Paris Commune and the concentration camps still serve as practical reference points for our lives.

To more emotionally and effectively portray the spirit of free community that the Paris Commune and the Commune fostered, we cast Rimbaud, a poet from the Paris Commune, and Shin Dong-yup, a poet from the Commune.

In this way, the philosophy of history is divided into four chapters.

There are chapters dealing with the Paris Commune, chapters dealing with Rimbaud, chapters dealing with the concentration camp, and chapters dealing with Shin Dong-yup.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Beginning lectures on the philosophy of history and political philosophy

prolog

Part 1 Beyond the Religious and the Contemplative

Philosophy of History Chapter 1: The Paris Commune Defended with Red Blood

BRIDGE: For the richness and pleasure of your car

Political Philosophy, Chapter 1: The Humanities Against Religion

1.

The First Path of Christian Criticism: From Feuerbach to Nietzsche

2.

The Second Path to Christian Criticism: Marx's Critique of Political Economy

3.

Capitalism as a Religion

Political Philosophy Chapter 2: Beyond Feuerbach

1.

From essence to relationship

2.

From observation to history

3.

From bourgeois society to human society

BRIDGE: International's Songs Revisited

The Poet Rimbaud, Who Witnessed the Paris Commune, Chapter 2 of Philosophy of History

Part 2: Marx's Philosophy, Marx's Science

Philosophy of History, Chapter 3: Ugeumchi's Heavenly Beings

BRIDGE: The days of the Jipsangso, as brilliant as the Paris Commune

Political Philosophy Chapter 3: Beyond Materialism and Idealism

1.

The concept of 'targeted activity': Marx's alpha and omega

2.

In search of the lost power of objective activity

3.

Prove and prove again the target activity!

Political Philosophy Chapter 4: Back to Marx

1.

Materialism of Encounter, or the Dialectics of Otherness

2.

The Teachings of the Paris Commune, or the Break with Engelsianism

3.

Criticism of social democracy, or criticism of the distribution debate

BRIDGE: Hello! Diamat! Hello! Engels

Philosophy of History, Chapter 4: The Blue Sky in the Poet's Eyes

Epilogue

References

prolog

Part 1 Beyond the Religious and the Contemplative

Philosophy of History Chapter 1: The Paris Commune Defended with Red Blood

BRIDGE: For the richness and pleasure of your car

Political Philosophy, Chapter 1: The Humanities Against Religion

1.

The First Path of Christian Criticism: From Feuerbach to Nietzsche

2.

The Second Path to Christian Criticism: Marx's Critique of Political Economy

3.

Capitalism as a Religion

Political Philosophy Chapter 2: Beyond Feuerbach

1.

From essence to relationship

2.

From observation to history

3.

From bourgeois society to human society

BRIDGE: International's Songs Revisited

The Poet Rimbaud, Who Witnessed the Paris Commune, Chapter 2 of Philosophy of History

Part 2: Marx's Philosophy, Marx's Science

Philosophy of History, Chapter 3: Ugeumchi's Heavenly Beings

BRIDGE: The days of the Jipsangso, as brilliant as the Paris Commune

Political Philosophy Chapter 3: Beyond Materialism and Idealism

1.

The concept of 'targeted activity': Marx's alpha and omega

2.

In search of the lost power of objective activity

3.

Prove and prove again the target activity!

Political Philosophy Chapter 4: Back to Marx

1.

Materialism of Encounter, or the Dialectics of Otherness

2.

The Teachings of the Paris Commune, or the Break with Engelsianism

3.

Criticism of social democracy, or criticism of the distribution debate

BRIDGE: Hello! Diamat! Hello! Engels

Philosophy of History, Chapter 4: The Blue Sky in the Poet's Eyes

Epilogue

References

Detailed image

Into the book

Yes, that's right.

What is important is the activity to “destroy the old society” right now.

First, revolutionaries must throw themselves into the practice of destroying the old society.

Only then will the crouching working class be able to overcome its sense of defeat.

The situation is one where a revolutionary proposes and the working class accepts the proposal.

Only through these activities can we hope for a new society that is just and equal.

--- p.58~59

Because revolution is a practice that eliminates the relationship between ‘ruler and ruled’ itself.

Naturally, the minorities who are parasitic on the majority and do nothing, such as gods, kings, landowners, and capitalists, will disappear.

Because no one is unemployed, a community where people help each other by exchanging the fruits of their labor, a community that Blanqui defined as a “union,” becomes possible.

Union is not difficult.

Because it is a form of community that aims for horizontal order and free solidarity both politically and economically.

--- p.60

Since the French Revolution of 1789, the working class has always been the decisive force in overthrowing oppressive regimes.

The problem is that after the system collapsed, the working class did not take power on its own.

So, a bunch of vested interests came to occupy the empty throne.

Fortunately, in 1871 the working class decided to take its own destiny into its own hands under the name of the Commune.

--- p.73

Let's think about it genealogically.

The strong rule over the weak.

In order to perpetuate their domination or to prevent resistance from the weak, the ruler imprints an inferiority complex on the ruled.

The ruled, obsessed with an inferiority complex, dream of a just and loving ruler.

Their dreams are condensed into a transcendent being called God, the most superior being.

In this respect, Christianity can be said to be the most sophisticated evangelized world.

--- p.156

This is where the irony of exploitation arises: the idle ruling class exploits the workers, who can live without working, and the less they work, the richer they become.

As Marx said, the Commune knew.

All inequality, or injustice, stems from the monopoly of the means of production.

So, if the means of production, such as land and capital, were returned to the producers, such as farmers and workers, inequality and injustice would disappear like spring snow melting away.

--- p.81

History is a sad reminder of how long the majority of humans have been domesticated by a minority.

Only then, from the standpoint of the oppressed, can they overcome a life of humiliation and disgrace by acknowledging humiliation as humiliation and disgrace as disgrace.

At the same time, it can prevent new attempts by the ruling class to create a world of inversion and confine the majority.

What we need is a history that remembers the blood and tears of the losers, not a history that justifies the winners.

--- p.164

The reason why oppressive systems always prosper is none other than this.

Because the oppressed people fall under the spell of the ruling class and believe that they are inferior.

An inferior person cannot spit on a superior person.

So, if we are to spit on the disgusting face of the capitalist system that oppresses and exploits humans and nature, we must first free ourselves from the sorcery of capitalism.

--- p.213

No matter how different they may appear on the surface, the entire Western philosophical tradition is rooted in this essentialism.

This is why Marx's assertion that "human nature is an ensemble of social relations" is important.

Instead of essentialism, Marx advocates a position that can be called 'relationalism'.

Relationalism is the view that it is not the objects that we can see, such as individuals or objects, but the relationships that are not directly visible that are important.

--- p.224

The same goes for workers.

Because capitalists monopolized the absolute means of production and livelihood, namely money, workers were left with only their labor power to sell.

However, workers who do not recognize the 'capitalist-laborer' relationship accept their situation as fate.

Now the dream he has left is simple.

You either dream of earning a lot of money or you dream of one day becoming a capitalist who hires workers.

If workers knew that their lives were miserable because of the capitalists, they would not be devoted to such vain dreams.

What is important is not that workers become capitalists, but that the 'capitalist-worker' relationship disappears.

--- p.247

Slavery ceases to exist when a slave becomes free, not because someone grants him freedom.

Because freedom is not something that others give you, it is something that you win for yourself.

--- p.308

So power suppresses human freedom by using life as bait.

In most cases, we choose to submit to power for the sake of biological life.

But sometimes, there are cases where people risk their lives to resist oppression.

At this very moment, power will realize that it can kill him, but it cannot enslave him.

But how difficult is this kind of free spirit?

--- p.375

If the concept of 'target activity' is the heart of Marx's philosophy, then the idea of 'human society' can be said to be the head of Marx's philosophy.

In this way, objective activity and human society are unified in Marx.

After all, a human society is a society in which all humans enjoy objective activities.

--- p.513

The final result was Capital, published in 1867.

So, the Paris Commune, which was established in 1871, could be said to have been a kind of gospel for Marx.

Because the Paris Commune itself proved that communism cannot, must not, and does not need to be reserved in the name of developing productive forces or economic development.

What is important is the activity to “destroy the old society” right now.

First, revolutionaries must throw themselves into the practice of destroying the old society.

Only then will the crouching working class be able to overcome its sense of defeat.

The situation is one where a revolutionary proposes and the working class accepts the proposal.

Only through these activities can we hope for a new society that is just and equal.

--- p.58~59

Because revolution is a practice that eliminates the relationship between ‘ruler and ruled’ itself.

Naturally, the minorities who are parasitic on the majority and do nothing, such as gods, kings, landowners, and capitalists, will disappear.

Because no one is unemployed, a community where people help each other by exchanging the fruits of their labor, a community that Blanqui defined as a “union,” becomes possible.

Union is not difficult.

Because it is a form of community that aims for horizontal order and free solidarity both politically and economically.

--- p.60

Since the French Revolution of 1789, the working class has always been the decisive force in overthrowing oppressive regimes.

The problem is that after the system collapsed, the working class did not take power on its own.

So, a bunch of vested interests came to occupy the empty throne.

Fortunately, in 1871 the working class decided to take its own destiny into its own hands under the name of the Commune.

--- p.73

Let's think about it genealogically.

The strong rule over the weak.

In order to perpetuate their domination or to prevent resistance from the weak, the ruler imprints an inferiority complex on the ruled.

The ruled, obsessed with an inferiority complex, dream of a just and loving ruler.

Their dreams are condensed into a transcendent being called God, the most superior being.

In this respect, Christianity can be said to be the most sophisticated evangelized world.

--- p.156

This is where the irony of exploitation arises: the idle ruling class exploits the workers, who can live without working, and the less they work, the richer they become.

As Marx said, the Commune knew.

All inequality, or injustice, stems from the monopoly of the means of production.

So, if the means of production, such as land and capital, were returned to the producers, such as farmers and workers, inequality and injustice would disappear like spring snow melting away.

--- p.81

History is a sad reminder of how long the majority of humans have been domesticated by a minority.

Only then, from the standpoint of the oppressed, can they overcome a life of humiliation and disgrace by acknowledging humiliation as humiliation and disgrace as disgrace.

At the same time, it can prevent new attempts by the ruling class to create a world of inversion and confine the majority.

What we need is a history that remembers the blood and tears of the losers, not a history that justifies the winners.

--- p.164

The reason why oppressive systems always prosper is none other than this.

Because the oppressed people fall under the spell of the ruling class and believe that they are inferior.

An inferior person cannot spit on a superior person.

So, if we are to spit on the disgusting face of the capitalist system that oppresses and exploits humans and nature, we must first free ourselves from the sorcery of capitalism.

--- p.213

No matter how different they may appear on the surface, the entire Western philosophical tradition is rooted in this essentialism.

This is why Marx's assertion that "human nature is an ensemble of social relations" is important.

Instead of essentialism, Marx advocates a position that can be called 'relationalism'.

Relationalism is the view that it is not the objects that we can see, such as individuals or objects, but the relationships that are not directly visible that are important.

--- p.224

The same goes for workers.

Because capitalists monopolized the absolute means of production and livelihood, namely money, workers were left with only their labor power to sell.

However, workers who do not recognize the 'capitalist-laborer' relationship accept their situation as fate.

Now the dream he has left is simple.

You either dream of earning a lot of money or you dream of one day becoming a capitalist who hires workers.

If workers knew that their lives were miserable because of the capitalists, they would not be devoted to such vain dreams.

What is important is not that workers become capitalists, but that the 'capitalist-worker' relationship disappears.

--- p.247

Slavery ceases to exist when a slave becomes free, not because someone grants him freedom.

Because freedom is not something that others give you, it is something that you win for yourself.

--- p.308

So power suppresses human freedom by using life as bait.

In most cases, we choose to submit to power for the sake of biological life.

But sometimes, there are cases where people risk their lives to resist oppression.

At this very moment, power will realize that it can kill him, but it cannot enslave him.

But how difficult is this kind of free spirit?

--- p.375

If the concept of 'target activity' is the heart of Marx's philosophy, then the idea of 'human society' can be said to be the head of Marx's philosophy.

In this way, objective activity and human society are unified in Marx.

After all, a human society is a society in which all humans enjoy objective activities.

--- p.513

The final result was Capital, published in 1867.

So, the Paris Commune, which was established in 1871, could be said to have been a kind of gospel for Marx.

Because the Paris Commune itself proved that communism cannot, must not, and does not need to be reserved in the name of developing productive forces or economic development.

--- p.592

Publisher's Review

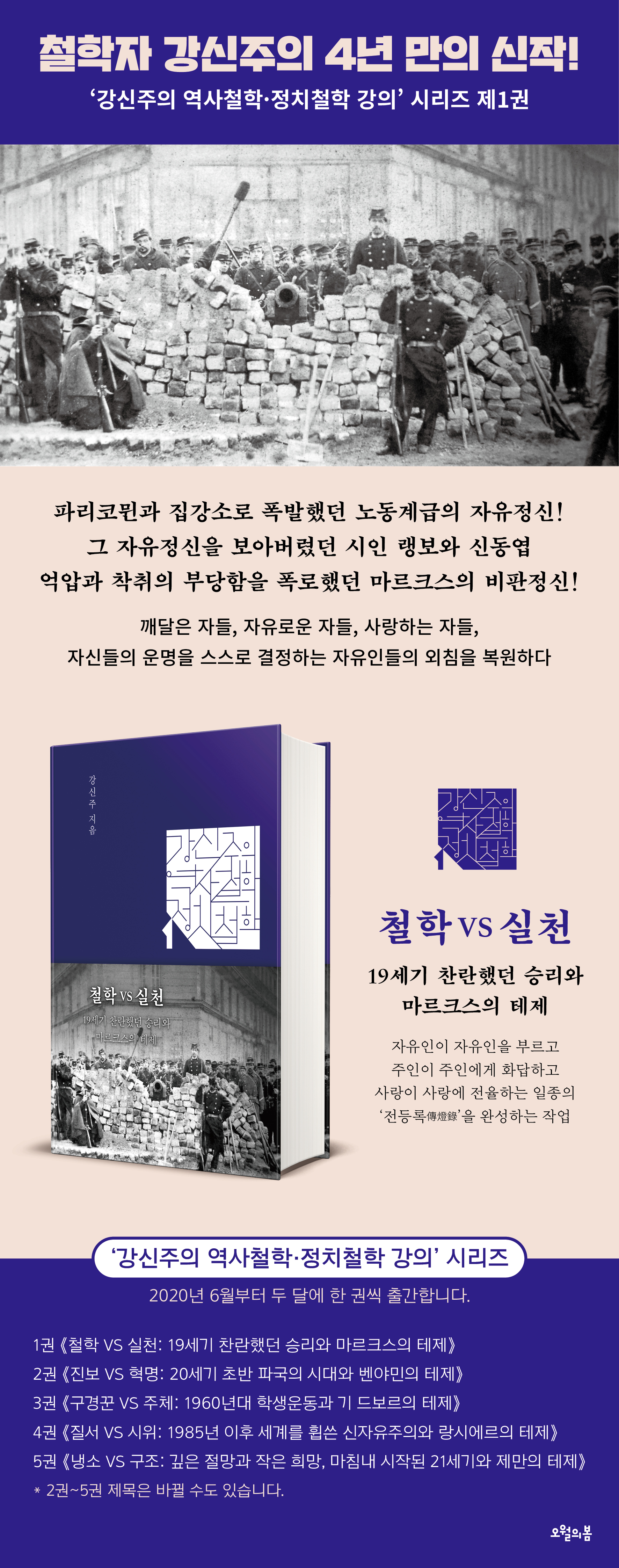

Philosopher Kang Shin-ju's new work after four years

Kang Shin-ju's Lecture Series on the Philosophy of History and Political Philosophy

Reviving the "Lamp Family" that resisted oppression

“Freedom cannot be taken away from someone who has tasted it.

You cannot make a person who has become the master of his own life a slave again.

“You can’t make someone hate someone who has come to love them.”

A capitalist system that originated in the mid-18th century and has persisted to this day.

How did humanity live during this period? Wasn't it a history of a small group of victors oppressing and leading the majority? Wasn't it a history of humans enslaving others, a history punctuated by victors? In fact, this history has persisted since the first class societies formed around 3000 BC.

A history of those who monopolized the means of production dominating, oppressing, and exploiting those who were deprived of the means of production.

This is the true nature of the oppressive system that has continued until now.

Philosopher Kang Shin-joo, who is releasing a new work after four years, confronts the history of this oppressive system.

By stripping away the essence of the oppressive system that has forced oppression and exploitation, it revives those who resisted it and those who fought against the oppressive system as masters of life and love.

This is a project to include the five volumes of 'Lectures on the Philosophy of History and Political Philosophy of Kang Shin-ju' about enlightened people, free people, and people who lived as masters.

This is also “the work of completing a kind of ‘Jeondeungrok’ in which free people call free people, masters respond to masters, and love trembles with love.”

It is a massive series, with even the shortest volumes exceeding 800 pages and the longest volumes reaching 1,300 pages.

In the case of philosophy of history, it covers the period from the Paris Commune of 1871 and the Gabo Peasant War of 1894 to the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020, and in the case of political philosophy, it covers the period from the mid-19th century to the early 21st century, focusing on Marx, Benjamin, Guy Debord, Rancière, and Zeeman.

In other words, the basic framework of this series is to encompass contemporary history and philosophy based on philosophical texts mentioned by five philosophers.

Although it covers a period of less than 200 years, the series has grown in scale as it sheds light on the people who fought against oppressive regimes from various perspectives.

Philosopher Kang Shin-ju focuses on the numerous people who have resisted the oppressive system, naming them the “Family of the Light.”

The first volume, Philosophy VS Practice, focuses on the fighters of the Paris Commune, the fighters of Woo Geum-chi's Donghak Peasant Army, the revolutionary Louis Blanqui, the poets Rimbaud and Shin Dong-yup, Marx, the fighters of the Roman Spartacus Legion, and the Russian philosopher Alexander Bogdanov. In the following volumes, Rosa Luxemburg, the fighters of the Spartacist League, Korsch, Gramsci, Shin Chae-ho, the fighters of the Kronstadt Soviet, George Orwell, the Spanish militia, Benjamin, Brecht, Joan Baez, Kim Su-young, Guy Debord, Che Guevara, Kim Min-ki, Ken Loach, Lee Chang-dong, Darwish, and Kim Seon-woo are vividly restored.

However, this does not mean that I am in any way defending revolutionaries like Lenin who succeeded in the revolution.

The Soviet system that emerged after the revolution is harshly criticized as nothing more than another oppressive system in which the state monopolizes the means of production.

Likewise, German social democrats, who emphasized distribution rather than revolution, are also subject to criticism.

Meanwhile, the oppressive regime has belittled, diminished, and distorted the countless resistances that have fought against them, calling them nothing more than “dreamers’ daydreams.”

He assessed the revolutionaries of the Paris Commune as reckless, and the activities of the Donghak Peasant Army as nothing more than a hasty misjudgment.

We are now assimilated into the ideology of the bourgeois system.

There is widespread cynicism that the light of resistance is nothing more than unnecessary adventurism and is doomed to failure.

But we live in a world where the more workers work, the poorer they become.

The world is full of people who are unaware of the ruling class.

Since the beginning of human civilization, there has never been a world where all people are equal.

Is this world just?

Reading this book clearly imprints this contradiction.

We are forced to face the tragic history of a small number of winners.

You will get a glimpse into the lives of countless free men who sacrificed their lives for freedom.

And soon you realize that the oppressed, the ordinary workers, are a huge majority, and at the same time that the oppressors are a small minority.

When we encounter the spirit of freedom and practice of the working class that exploded with the Paris Commune and the concentration camps, and the critical spirit of Marx that exposed the injustice and unfairness of oppression and exploitation, we naturally begin to yearn for a society free from oppression.

‘Practice to become a free person’ – this is the meaning of reading this book.

When you finish reading the book, you will have a powerful force that will enable you to plan not the Paris Commune or the guild halls of the 19th century, but the communes and guild halls of the 21st century.

You will also be able to catch a glimpse of the true nature of Marx's philosophy once again.

The structure of the first volume, Philosophy vs. Practice

4 chapters on philosophy of history, 4 chapters on political philosophy

The first volume, entitled Philosophy vs. Practice, consists of four chapters on the philosophy of history and four chapters on political philosophy.

First, the four chapters on the philosophy of history are devoted to vividly restoring the grandeur and immense scale of the Paris Commune and the concentration camps.

Explains what exactly happened within the Paris Commune and the concentration camps, and why the Paris Commune and the concentration camps still serve as practical reference points for our lives.

To more emotionally and effectively portray the spirit of free community that the Paris Commune and the Commune fostered, we cast Rimbaud, a poet from the Paris Commune, and Shin Dong-yup, a poet from the Commune.

In this way, the philosophy of history is divided into four chapters.

There are chapters dealing with the Paris Commune, chapters dealing with Rimbaud, chapters dealing with the concentration camp, and chapters dealing with Shin Dong-yup.

In contrast, the four chapters on political philosophy are devoted entirely to Marx. The 19th century was the first time since 3000 BC that the working class was attempting to overcome the very relations of domination.

It was Marx who sought to provide theoretical justification and practical perspective for the spirit and practice of the working class to throw off the shackles of oppression and exploitation.

Marx was a philosopher who supported the spirit of the 19th century working class, which pursued a free community, and at the same time, he was a practitioner who tried to achieve it himself.

To revive Marx's prestige not as a "dead dog" but as an "indomitable lion," to demonstrate that he is not a stuffed intellectual from the 19th century but a powerful philosopher still relevant in the 21st century—this is the mission of the four chapters on political philosophy.

The core is the Theses on Feuerbach, completed in 1845 when Marx was 27 years old.

Ideologists in established socialist countries usually interpret this document as an expression of the immature thinking of the 'young Marx'.

However, the Theses on Feuerbach are the culmination and completion of Marx's philosophy.

These short theses strongly assert the idea that all humans, including the working class, are subjects of 'objective activity' and that a society in which the working class exercises its capacity for objective activity is a 'human society'.

This is precisely why the title of the first volume is ‘Philosophy VS Practice.’

This is because Marx rejected a philosophy that was irrelevant to practice and sought to complete a philosophy that opened up practical perspectives.

The core task of the first volume, political philosophy, is that Marx's philosophy, summarized as 'target activity' and 'human society,' permeates Marx's thoughts and practices in his youth, middle age, and later years.

And after reading this chapter on Marx, you will realize how outdated the Marxism that has been going on up until now is.

You will encounter a new Marxism not as a conflict between 'materialism and idealism', but as a practical philosophy that transcends that conflict.

Finally, there is a chapter called 'BRIDGE' placed between the chapters on the philosophy of history and the chapters on political philosophy.

It is a place to rest a little, like an oasis in the desert, but at the same time, it is also an element that enriches the discussion.

To enrich your reading of the Paris Commune, the workshops, and Marx's philosophy, we've included "For the Richness and Pleasure of the Car," "Songs of the Internationale Revisited," "The Workshop Days as Brilliant as the Paris Commune," and "Goodbye! Diamat! Goodbye! Engels."

The Paris Commune and the Gathering House: The Realization of a Free Community

"Philosophy vs. Practice" takes us to the 19th century, when the bourgeois system was in full swing.

At that time, the bourgeois system was a system that could not survive without mass producing workers.

This is because the logic of capitalism is to reform the majority of people so that they can make a living by selling their labor to capital and to leave surplus value through their labor.

But at that time, the workers did not waver at all on the front line between labor and capital.

The majority chose to fight head-on against capital's oppression and exploitation of labor.

The Paris Commune in the West in 1871 and the concentration camps established by the Donghak Peasant Revolution in Korea in 1894 are vivid historical evidence and testimonies.

The Paris Commune and the Commune of Congress sought, and achieved, for the first time since 3000 BC, the birth of the oppressive apparatus known as the state, a free community free from oppression and exploitation, albeit in a short period of time.

The Paris Commune of 1871 symbolized the revolution in which the working class of the great city of Paris, that is, the workers, took back the means of production that had been monopolized by the bourgeoisie, and the Gabo Peasant Revolution of 1894, that is, the Jippangso, symbolized the revolution in which the working class, that is, the peasants, took back the means of production that had been monopolized by the landlords.

This is precisely why the 19th century is called 'the days of brilliant victory' in this book.

The workers of Paris and the peasants of Joseon, in a time of chaos when landowners and capitalists were competing for the throne of the ruling class, dreamed of a society in which the ruling class itself would be abolished and oppression and exploitation would no longer be possible.

Their goal was to create a community of free individuals.

A society where the working class has successfully reclaimed not only the means of production but also the means of violence and politics! No longer a society where the fate of the majority is determined by the minority, but a society where the majority determines their own destiny! The workers of Paris and the peasants of Joseon actually created and implemented such a society.

This is precisely the community that Marx dreamed of as ‘human society’ and that Choi Je-woo dreamed of as ‘Innaecheon.’

The first volume of 'Kang Shin-ju's Lectures on the Philosophy of History and Political Philosophy', 'Philosophy VS Practice', aims to vividly show the appearance of this free community in the present age.

The community that poet Rimbaud saw and that Shin Dong-yup saw.

The purpose is to revive in this day and age the spirit of freedom of those who sought neither to rule nor be ruled by anyone.

Separating Marx's philosophy from Engels or Lenin

What exactly is Marx's philosophy? We once understood Marx's philosophy through concepts like "dialectical materialism" and "historical materialism," imported from the Soviet Union.

This was a term coined by the Soviet philosopher Plekhanov and established by Stalin.

In other words, we came to understand Marx's philosophy through the Stalinist regime.

The author says that this is nothing more than a misunderstanding and distortion of Marx's philosophy.

They even argue that Engels and Marx should be considered separately.

This is because Engels was the first person to explain Marx's philosophy by naming it 'materialist dialectics.'

Engels systematized Marx's materialism in his works from 1873 to 1888: Anti-Dühring, Dialectics of Nature, The Development of Socialism from Utopia to Science, and finally Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy.

However, the author criticizes this work for confining Marx's philosophy to a vast metaphysical system.

Plekhanov's philosophy, which expands on Engels's argument, is simple.

It is argued that everything can be explained by the dialectical movement of substances.

Likewise, he argues that society can be explained not through ideological things like politics or law, but through material things like the economy, and through dialectics.

In other words, if we recognize the actual relationships given through the production process, that is, economic relationships, we can find corresponding laws as well as dialectical laws.

All that remains for us is to obey this law absolutely.

This is a discussion in which the metaphysical materialism and scientific epistemology advocated by Engels are directly applied.

The characteristics of Engels and Plekhanov's thinking can be summarized as legitimacy based on elitism and economism that emphasizes the development of productive forces.

The idea is that a small number of elites must lead the majority of people, and that socialism cannot be completed unless productivity develops.

It was Russian revolutionaries, including Lenin, who accepted this.

The Soviet Union they created was nothing more than another form of capitalism, a state-monopoly capitalist system that promoted state-centered economic development rather than the spontaneity of the working class.

The author criticizes the Soviet Union, which claimed to have inherited Marx's philosophy, as being in fact merely a result of distorting Marx's philosophy.

Therefore, he says, we should also abandon terms like Marxism-Engelism and Marxism-Leninism.

Because those terms are nothing more than Marxism seen through the eyes of Engels and Lenin.

In fact, Marx did not use terms such as ‘materialist dialectics’, ‘dialectical materialism’, or ‘historical materialism’.

Because the metaphysical claim that everything is determined by dialectical laws is nothing more than 'old materialism' in Marx's eyes.

Marx was neither an idealist who emphasized only human spontaneity and freedom, nor a materialist who believed that humans were determined by external circumstances, economic conditions, or material circumstances.

He was a philosopher who resolved the age-old conflict in the history of philosophy, that is, the conflict between idealism and materialism, with the concept of 'objective activity.'

In the tenth thesis of “Theses on Feuerbach,” Marx also distinguished between “old materialism” and “new materialism.”

“The standpoint of old materialism is ‘bourgeois society,’ and the standpoint of new materialism is ‘human society’ or ‘social man.’” In other words, Marx’s ‘new materialism’ was about standing with the oppressed and accompanying them in their struggle.

The Essence of Marx's Philosophy (1) 'Objective Activity'

A practical and participatory philosophy that addresses given conditions

So what is Marx's philosophy? The author argues that understanding "objective activity" and "human society" is key.

The document that the author considers important is “Theses on Feuerbach,” written by Marx when he was 27 years old.

Althusser, a philosopher influenced by Engels, says that the distinction between the 'young Marx' and the 'middle-aged Marx' began around 1845.

And most scholars have disparaged the philosophy of the 'young Marx' as an immature work (Althusser himself retracted this in his later years, writing "The Secret Current of the Materialism of Encounter").

However, the author believes that Marx's philosophy, summarized as 'target activity' and 'human society', runs through Marx's thoughts and practices in his youth, middle age, and later years.

In other words, the reason Marx devoted himself to the study of political economy rather than philosophy after the age of 30 is because he had already 'completed' philosophy with "Theses on Feuerbach" at the age of 27.

The first thesis of “Theses on Feuerbach” begins like this:

“The main defect of all materialism up to now, including Feuerbach’s materialism, is that it has thought of things, reality, and sensibility only in the form of objects or intuitions, and not subjectively, as sensuous human activity or practice.

Therefore, the active aspect was developed by idealism in contrast to materialism, but its development was only abstract, since idealism does not know the real and emotional activity itself.

Feuerbach wanted objects of the senses that were realistically separate from objects of thought, but he did not consider human activity itself to be objective activity.

Therefore, in The Essence of Christianity, he regards only the theoretical attitude as the truly human attitude, while practice is understood and fixed only in its dirty Jewish form of phenomenon.

Therefore, he does not understand the meaning of ‘revolutionary’ activity, that is, ‘practical-critical’ activity.”

The first thesis is the most important.

Every sentence in the first thesis looks at one concept.

It is precisely 'targeted activity Gegenstandliche Tatigkeit'.

Whether materialism or idealism, it slips away like sand in the hands of philosophers who are content to interpret the world, but it is a concept that all ordinary people, that is, working people, who have tried to change the world, even if only in a small way, know as part of their lives.

Because 'target activity' is a concept related to change, not interpretation, and to practice, not contemplation.

The concept of 'objective activity' is that we are beings who cannot help but act and resist against something that frustrates our will, makes our lives uncomfortable, and further tests our strength, something like an unavoidable resistance that we encounter in life.

For Marx, the new materialism was the affirmation that each human being was a practical subject engaged in objective activity.

The term 'objective' refers to the passivity of human life, meaning that human life does not begin from a blank slate, but must begin from conditions of life that cannot be helped.

On the other hand, 'activity' refers to the active nature of human life, meaning that humans do not passively adapt to the given conditions of life but actively overcome them.

The author emphasizes that Marx's thinking is practical and participatory in that it emphasizes activities that overcome given conditions rather than succumbing to them.

Marx goes beyond old materialism and idealism with the concept of 'objective activity'.

In other words, if the limitation of old materialism, including Feuerbach, was that it did not recognize the active aspect of human beings, the limitation of idealism is that it did not recognize the passive aspect of human beings.

In 1845, the young philosopher Marx, at the age of 27, had already completed a new materialism, that is, his own philosophy.

The reason Marx devoted himself to the study of 『Das Kapital』 from the 1860s onwards was, above all, because he needed an accurate understanding of the objective conditions.

Not to conform to the laws of the capitalist system, but to overcome them; not to despair of the ruthless capitalist system, but to overcome it.

The Essence of Marx's Philosophy (2) 'Human Society'

A philosophy that changes the world, not a philosophy that interprets the world.

Another concept of Marxist philosophy that the author emphasizes is ‘human society.’

If bourgeois society is a society led by the capitalist class, then human society is a society led by all humans, not a specific class.

Of course, human society is not a society led by slave owners, nor a society led by lords or landowners, nor a society led by a party or leader like the former Soviet Union, China, or North Korea, which advocated Stalinism.

It is also not a society led by capitalists.

In other words, human society is not a society where a minority leads or commands the majority, but a society where all humans lead.

More specifically, the 'human society' that Marx wanted to establish is a society in which everyone enjoys objective activities.

It is a society in which nationalization of the means of production by the state or privatization of the means of production by the capitalist class has disappeared, a society in which sharing or monopolization of the means of production is impossible, that is, a society in which communism has been realized.

In The German Ideology, Marx said, “In a truly real community, each individual attains his freedom only in and through his association.”

In other words, a society that unites through freedom and becomes free through solidarity was the slogan of human society.

“If cooperative production were to replace the capitalist system, if united societies were to regulate national production according to a common plan, and thus take national economy under their own control, and put an end to the permanent anarchy and periodic fluctuations which are the scourges of capitalist production – what else, gentlemen, would be communism, ‘possible’ communism?” (The Civil War in France) Communism, Marx’s ideology of human society, was the stance that permeated his entire life.

The most convincing evidence is 『The Civil War in France』, published in 1871.

When the Paris Commune of 1871 briefly established a human society, Marx wrote The Civil War in France and paid tribute to the Paris Commune.

This book was Marx's hymn to the Paris Commune, a community of free individuals that, although frustrated in reality, succeeded in securing eternity as an ideology.

In this book, Marx highly praised the Paris Commune's will to place the means of production, political means, and even the means of violence in the hands of the people, and argued that this was true communism, or possible communism.

Unlike Engels, who argued that communism was only possible if productive forces developed, Marx argued that the idea of a “human society” could be realized at any time, regardless of whether productive forces developed or not, or whether economic development occurred.

The final thesis of “Theses on Feuerbach” ends like this:

“Philosophers have simply interpreted the world in various ways.

But the important thing is to change the world.” This thesis may have been Marx’s pledge in his youth.

Marx himself was the embodiment of 'objective activity' and was also a practitioner who acted for the 'human society' and 'communal society' he proclaimed.

Marx's philosophy is not a philosophy that interprets the world, but a philosophy that changes the world; not a philosophy that observes the world, but a philosophy that puts it into practice.

This book helps us to face Marx's practical philosophy again, by removing the shadows of Engels, Lenin, and Stalin.

Kang Shin-ju's Lecture Series on the Philosophy of History and Political Philosophy

Reviving the "Lamp Family" that resisted oppression

“Freedom cannot be taken away from someone who has tasted it.

You cannot make a person who has become the master of his own life a slave again.

“You can’t make someone hate someone who has come to love them.”

A capitalist system that originated in the mid-18th century and has persisted to this day.

How did humanity live during this period? Wasn't it a history of a small group of victors oppressing and leading the majority? Wasn't it a history of humans enslaving others, a history punctuated by victors? In fact, this history has persisted since the first class societies formed around 3000 BC.

A history of those who monopolized the means of production dominating, oppressing, and exploiting those who were deprived of the means of production.

This is the true nature of the oppressive system that has continued until now.

Philosopher Kang Shin-joo, who is releasing a new work after four years, confronts the history of this oppressive system.

By stripping away the essence of the oppressive system that has forced oppression and exploitation, it revives those who resisted it and those who fought against the oppressive system as masters of life and love.

This is a project to include the five volumes of 'Lectures on the Philosophy of History and Political Philosophy of Kang Shin-ju' about enlightened people, free people, and people who lived as masters.

This is also “the work of completing a kind of ‘Jeondeungrok’ in which free people call free people, masters respond to masters, and love trembles with love.”

It is a massive series, with even the shortest volumes exceeding 800 pages and the longest volumes reaching 1,300 pages.

In the case of philosophy of history, it covers the period from the Paris Commune of 1871 and the Gabo Peasant War of 1894 to the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020, and in the case of political philosophy, it covers the period from the mid-19th century to the early 21st century, focusing on Marx, Benjamin, Guy Debord, Rancière, and Zeeman.

In other words, the basic framework of this series is to encompass contemporary history and philosophy based on philosophical texts mentioned by five philosophers.

Although it covers a period of less than 200 years, the series has grown in scale as it sheds light on the people who fought against oppressive regimes from various perspectives.

Philosopher Kang Shin-ju focuses on the numerous people who have resisted the oppressive system, naming them the “Family of the Light.”

The first volume, Philosophy VS Practice, focuses on the fighters of the Paris Commune, the fighters of Woo Geum-chi's Donghak Peasant Army, the revolutionary Louis Blanqui, the poets Rimbaud and Shin Dong-yup, Marx, the fighters of the Roman Spartacus Legion, and the Russian philosopher Alexander Bogdanov. In the following volumes, Rosa Luxemburg, the fighters of the Spartacist League, Korsch, Gramsci, Shin Chae-ho, the fighters of the Kronstadt Soviet, George Orwell, the Spanish militia, Benjamin, Brecht, Joan Baez, Kim Su-young, Guy Debord, Che Guevara, Kim Min-ki, Ken Loach, Lee Chang-dong, Darwish, and Kim Seon-woo are vividly restored.

However, this does not mean that I am in any way defending revolutionaries like Lenin who succeeded in the revolution.

The Soviet system that emerged after the revolution is harshly criticized as nothing more than another oppressive system in which the state monopolizes the means of production.

Likewise, German social democrats, who emphasized distribution rather than revolution, are also subject to criticism.

Meanwhile, the oppressive regime has belittled, diminished, and distorted the countless resistances that have fought against them, calling them nothing more than “dreamers’ daydreams.”

He assessed the revolutionaries of the Paris Commune as reckless, and the activities of the Donghak Peasant Army as nothing more than a hasty misjudgment.

We are now assimilated into the ideology of the bourgeois system.

There is widespread cynicism that the light of resistance is nothing more than unnecessary adventurism and is doomed to failure.

But we live in a world where the more workers work, the poorer they become.

The world is full of people who are unaware of the ruling class.

Since the beginning of human civilization, there has never been a world where all people are equal.

Is this world just?

Reading this book clearly imprints this contradiction.

We are forced to face the tragic history of a small number of winners.

You will get a glimpse into the lives of countless free men who sacrificed their lives for freedom.

And soon you realize that the oppressed, the ordinary workers, are a huge majority, and at the same time that the oppressors are a small minority.

When we encounter the spirit of freedom and practice of the working class that exploded with the Paris Commune and the concentration camps, and the critical spirit of Marx that exposed the injustice and unfairness of oppression and exploitation, we naturally begin to yearn for a society free from oppression.

‘Practice to become a free person’ – this is the meaning of reading this book.

When you finish reading the book, you will have a powerful force that will enable you to plan not the Paris Commune or the guild halls of the 19th century, but the communes and guild halls of the 21st century.

You will also be able to catch a glimpse of the true nature of Marx's philosophy once again.

The structure of the first volume, Philosophy vs. Practice

4 chapters on philosophy of history, 4 chapters on political philosophy

The first volume, entitled Philosophy vs. Practice, consists of four chapters on the philosophy of history and four chapters on political philosophy.

First, the four chapters on the philosophy of history are devoted to vividly restoring the grandeur and immense scale of the Paris Commune and the concentration camps.

Explains what exactly happened within the Paris Commune and the concentration camps, and why the Paris Commune and the concentration camps still serve as practical reference points for our lives.

To more emotionally and effectively portray the spirit of free community that the Paris Commune and the Commune fostered, we cast Rimbaud, a poet from the Paris Commune, and Shin Dong-yup, a poet from the Commune.

In this way, the philosophy of history is divided into four chapters.

There are chapters dealing with the Paris Commune, chapters dealing with Rimbaud, chapters dealing with the concentration camp, and chapters dealing with Shin Dong-yup.

In contrast, the four chapters on political philosophy are devoted entirely to Marx. The 19th century was the first time since 3000 BC that the working class was attempting to overcome the very relations of domination.

It was Marx who sought to provide theoretical justification and practical perspective for the spirit and practice of the working class to throw off the shackles of oppression and exploitation.

Marx was a philosopher who supported the spirit of the 19th century working class, which pursued a free community, and at the same time, he was a practitioner who tried to achieve it himself.

To revive Marx's prestige not as a "dead dog" but as an "indomitable lion," to demonstrate that he is not a stuffed intellectual from the 19th century but a powerful philosopher still relevant in the 21st century—this is the mission of the four chapters on political philosophy.

The core is the Theses on Feuerbach, completed in 1845 when Marx was 27 years old.

Ideologists in established socialist countries usually interpret this document as an expression of the immature thinking of the 'young Marx'.

However, the Theses on Feuerbach are the culmination and completion of Marx's philosophy.

These short theses strongly assert the idea that all humans, including the working class, are subjects of 'objective activity' and that a society in which the working class exercises its capacity for objective activity is a 'human society'.

This is precisely why the title of the first volume is ‘Philosophy VS Practice.’

This is because Marx rejected a philosophy that was irrelevant to practice and sought to complete a philosophy that opened up practical perspectives.

The core task of the first volume, political philosophy, is that Marx's philosophy, summarized as 'target activity' and 'human society,' permeates Marx's thoughts and practices in his youth, middle age, and later years.

And after reading this chapter on Marx, you will realize how outdated the Marxism that has been going on up until now is.

You will encounter a new Marxism not as a conflict between 'materialism and idealism', but as a practical philosophy that transcends that conflict.

Finally, there is a chapter called 'BRIDGE' placed between the chapters on the philosophy of history and the chapters on political philosophy.

It is a place to rest a little, like an oasis in the desert, but at the same time, it is also an element that enriches the discussion.

To enrich your reading of the Paris Commune, the workshops, and Marx's philosophy, we've included "For the Richness and Pleasure of the Car," "Songs of the Internationale Revisited," "The Workshop Days as Brilliant as the Paris Commune," and "Goodbye! Diamat! Goodbye! Engels."

The Paris Commune and the Gathering House: The Realization of a Free Community

"Philosophy vs. Practice" takes us to the 19th century, when the bourgeois system was in full swing.

At that time, the bourgeois system was a system that could not survive without mass producing workers.

This is because the logic of capitalism is to reform the majority of people so that they can make a living by selling their labor to capital and to leave surplus value through their labor.

But at that time, the workers did not waver at all on the front line between labor and capital.

The majority chose to fight head-on against capital's oppression and exploitation of labor.

The Paris Commune in the West in 1871 and the concentration camps established by the Donghak Peasant Revolution in Korea in 1894 are vivid historical evidence and testimonies.

The Paris Commune and the Commune of Congress sought, and achieved, for the first time since 3000 BC, the birth of the oppressive apparatus known as the state, a free community free from oppression and exploitation, albeit in a short period of time.

The Paris Commune of 1871 symbolized the revolution in which the working class of the great city of Paris, that is, the workers, took back the means of production that had been monopolized by the bourgeoisie, and the Gabo Peasant Revolution of 1894, that is, the Jippangso, symbolized the revolution in which the working class, that is, the peasants, took back the means of production that had been monopolized by the landlords.

This is precisely why the 19th century is called 'the days of brilliant victory' in this book.

The workers of Paris and the peasants of Joseon, in a time of chaos when landowners and capitalists were competing for the throne of the ruling class, dreamed of a society in which the ruling class itself would be abolished and oppression and exploitation would no longer be possible.

Their goal was to create a community of free individuals.

A society where the working class has successfully reclaimed not only the means of production but also the means of violence and politics! No longer a society where the fate of the majority is determined by the minority, but a society where the majority determines their own destiny! The workers of Paris and the peasants of Joseon actually created and implemented such a society.

This is precisely the community that Marx dreamed of as ‘human society’ and that Choi Je-woo dreamed of as ‘Innaecheon.’

The first volume of 'Kang Shin-ju's Lectures on the Philosophy of History and Political Philosophy', 'Philosophy VS Practice', aims to vividly show the appearance of this free community in the present age.

The community that poet Rimbaud saw and that Shin Dong-yup saw.

The purpose is to revive in this day and age the spirit of freedom of those who sought neither to rule nor be ruled by anyone.

Separating Marx's philosophy from Engels or Lenin

What exactly is Marx's philosophy? We once understood Marx's philosophy through concepts like "dialectical materialism" and "historical materialism," imported from the Soviet Union.

This was a term coined by the Soviet philosopher Plekhanov and established by Stalin.

In other words, we came to understand Marx's philosophy through the Stalinist regime.

The author says that this is nothing more than a misunderstanding and distortion of Marx's philosophy.

They even argue that Engels and Marx should be considered separately.

This is because Engels was the first person to explain Marx's philosophy by naming it 'materialist dialectics.'

Engels systematized Marx's materialism in his works from 1873 to 1888: Anti-Dühring, Dialectics of Nature, The Development of Socialism from Utopia to Science, and finally Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy.

However, the author criticizes this work for confining Marx's philosophy to a vast metaphysical system.

Plekhanov's philosophy, which expands on Engels's argument, is simple.

It is argued that everything can be explained by the dialectical movement of substances.

Likewise, he argues that society can be explained not through ideological things like politics or law, but through material things like the economy, and through dialectics.

In other words, if we recognize the actual relationships given through the production process, that is, economic relationships, we can find corresponding laws as well as dialectical laws.

All that remains for us is to obey this law absolutely.

This is a discussion in which the metaphysical materialism and scientific epistemology advocated by Engels are directly applied.

The characteristics of Engels and Plekhanov's thinking can be summarized as legitimacy based on elitism and economism that emphasizes the development of productive forces.

The idea is that a small number of elites must lead the majority of people, and that socialism cannot be completed unless productivity develops.

It was Russian revolutionaries, including Lenin, who accepted this.

The Soviet Union they created was nothing more than another form of capitalism, a state-monopoly capitalist system that promoted state-centered economic development rather than the spontaneity of the working class.

The author criticizes the Soviet Union, which claimed to have inherited Marx's philosophy, as being in fact merely a result of distorting Marx's philosophy.

Therefore, he says, we should also abandon terms like Marxism-Engelism and Marxism-Leninism.

Because those terms are nothing more than Marxism seen through the eyes of Engels and Lenin.

In fact, Marx did not use terms such as ‘materialist dialectics’, ‘dialectical materialism’, or ‘historical materialism’.

Because the metaphysical claim that everything is determined by dialectical laws is nothing more than 'old materialism' in Marx's eyes.

Marx was neither an idealist who emphasized only human spontaneity and freedom, nor a materialist who believed that humans were determined by external circumstances, economic conditions, or material circumstances.

He was a philosopher who resolved the age-old conflict in the history of philosophy, that is, the conflict between idealism and materialism, with the concept of 'objective activity.'

In the tenth thesis of “Theses on Feuerbach,” Marx also distinguished between “old materialism” and “new materialism.”

“The standpoint of old materialism is ‘bourgeois society,’ and the standpoint of new materialism is ‘human society’ or ‘social man.’” In other words, Marx’s ‘new materialism’ was about standing with the oppressed and accompanying them in their struggle.

The Essence of Marx's Philosophy (1) 'Objective Activity'

A practical and participatory philosophy that addresses given conditions

So what is Marx's philosophy? The author argues that understanding "objective activity" and "human society" is key.

The document that the author considers important is “Theses on Feuerbach,” written by Marx when he was 27 years old.

Althusser, a philosopher influenced by Engels, says that the distinction between the 'young Marx' and the 'middle-aged Marx' began around 1845.

And most scholars have disparaged the philosophy of the 'young Marx' as an immature work (Althusser himself retracted this in his later years, writing "The Secret Current of the Materialism of Encounter").

However, the author believes that Marx's philosophy, summarized as 'target activity' and 'human society', runs through Marx's thoughts and practices in his youth, middle age, and later years.

In other words, the reason Marx devoted himself to the study of political economy rather than philosophy after the age of 30 is because he had already 'completed' philosophy with "Theses on Feuerbach" at the age of 27.

The first thesis of “Theses on Feuerbach” begins like this:

“The main defect of all materialism up to now, including Feuerbach’s materialism, is that it has thought of things, reality, and sensibility only in the form of objects or intuitions, and not subjectively, as sensuous human activity or practice.

Therefore, the active aspect was developed by idealism in contrast to materialism, but its development was only abstract, since idealism does not know the real and emotional activity itself.

Feuerbach wanted objects of the senses that were realistically separate from objects of thought, but he did not consider human activity itself to be objective activity.

Therefore, in The Essence of Christianity, he regards only the theoretical attitude as the truly human attitude, while practice is understood and fixed only in its dirty Jewish form of phenomenon.

Therefore, he does not understand the meaning of ‘revolutionary’ activity, that is, ‘practical-critical’ activity.”

The first thesis is the most important.

Every sentence in the first thesis looks at one concept.

It is precisely 'targeted activity Gegenstandliche Tatigkeit'.

Whether materialism or idealism, it slips away like sand in the hands of philosophers who are content to interpret the world, but it is a concept that all ordinary people, that is, working people, who have tried to change the world, even if only in a small way, know as part of their lives.

Because 'target activity' is a concept related to change, not interpretation, and to practice, not contemplation.

The concept of 'objective activity' is that we are beings who cannot help but act and resist against something that frustrates our will, makes our lives uncomfortable, and further tests our strength, something like an unavoidable resistance that we encounter in life.

For Marx, the new materialism was the affirmation that each human being was a practical subject engaged in objective activity.

The term 'objective' refers to the passivity of human life, meaning that human life does not begin from a blank slate, but must begin from conditions of life that cannot be helped.

On the other hand, 'activity' refers to the active nature of human life, meaning that humans do not passively adapt to the given conditions of life but actively overcome them.

The author emphasizes that Marx's thinking is practical and participatory in that it emphasizes activities that overcome given conditions rather than succumbing to them.

Marx goes beyond old materialism and idealism with the concept of 'objective activity'.

In other words, if the limitation of old materialism, including Feuerbach, was that it did not recognize the active aspect of human beings, the limitation of idealism is that it did not recognize the passive aspect of human beings.

In 1845, the young philosopher Marx, at the age of 27, had already completed a new materialism, that is, his own philosophy.

The reason Marx devoted himself to the study of 『Das Kapital』 from the 1860s onwards was, above all, because he needed an accurate understanding of the objective conditions.

Not to conform to the laws of the capitalist system, but to overcome them; not to despair of the ruthless capitalist system, but to overcome it.

The Essence of Marx's Philosophy (2) 'Human Society'

A philosophy that changes the world, not a philosophy that interprets the world.

Another concept of Marxist philosophy that the author emphasizes is ‘human society.’

If bourgeois society is a society led by the capitalist class, then human society is a society led by all humans, not a specific class.

Of course, human society is not a society led by slave owners, nor a society led by lords or landowners, nor a society led by a party or leader like the former Soviet Union, China, or North Korea, which advocated Stalinism.

It is also not a society led by capitalists.

In other words, human society is not a society where a minority leads or commands the majority, but a society where all humans lead.

More specifically, the 'human society' that Marx wanted to establish is a society in which everyone enjoys objective activities.

It is a society in which nationalization of the means of production by the state or privatization of the means of production by the capitalist class has disappeared, a society in which sharing or monopolization of the means of production is impossible, that is, a society in which communism has been realized.

In The German Ideology, Marx said, “In a truly real community, each individual attains his freedom only in and through his association.”

In other words, a society that unites through freedom and becomes free through solidarity was the slogan of human society.

“If cooperative production were to replace the capitalist system, if united societies were to regulate national production according to a common plan, and thus take national economy under their own control, and put an end to the permanent anarchy and periodic fluctuations which are the scourges of capitalist production – what else, gentlemen, would be communism, ‘possible’ communism?” (The Civil War in France) Communism, Marx’s ideology of human society, was the stance that permeated his entire life.

The most convincing evidence is 『The Civil War in France』, published in 1871.

When the Paris Commune of 1871 briefly established a human society, Marx wrote The Civil War in France and paid tribute to the Paris Commune.

This book was Marx's hymn to the Paris Commune, a community of free individuals that, although frustrated in reality, succeeded in securing eternity as an ideology.

In this book, Marx highly praised the Paris Commune's will to place the means of production, political means, and even the means of violence in the hands of the people, and argued that this was true communism, or possible communism.

Unlike Engels, who argued that communism was only possible if productive forces developed, Marx argued that the idea of a “human society” could be realized at any time, regardless of whether productive forces developed or not, or whether economic development occurred.

The final thesis of “Theses on Feuerbach” ends like this:

“Philosophers have simply interpreted the world in various ways.

But the important thing is to change the world.” This thesis may have been Marx’s pledge in his youth.

Marx himself was the embodiment of 'objective activity' and was also a practitioner who acted for the 'human society' and 'communal society' he proclaimed.

Marx's philosophy is not a philosophy that interprets the world, but a philosophy that changes the world; not a philosophy that observes the world, but a philosophy that puts it into practice.

This book helps us to face Marx's practical philosophy again, by removing the shadows of Engels, Lenin, and Stalin.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: June 10, 2020

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 848 pages | 1,144g | 140*207*40mm

- ISBN13: 9791190422345

- ISBN10: 1190422344

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)