Wild Comfort

|

Description

Book Introduction

UK Amazon Bestseller!

A book that lets you glimpse the spring outside without leaving the living room.

A memoir by a museum historian who suffered from depression for half his life.

A twelve-month record of flowers, plants, and animals that will build your mental strength for the next season.

“It’s definitely comforting to know that I can do something for myself, even on a gloomy day.”

Emma Mitchell suffered from depression for 25 years.

"The Consolation of the Wild" is a memoir about the depression he suffered from for half his life, and also a year-long diary about the solace he found in nature during several episodes of severe depression.

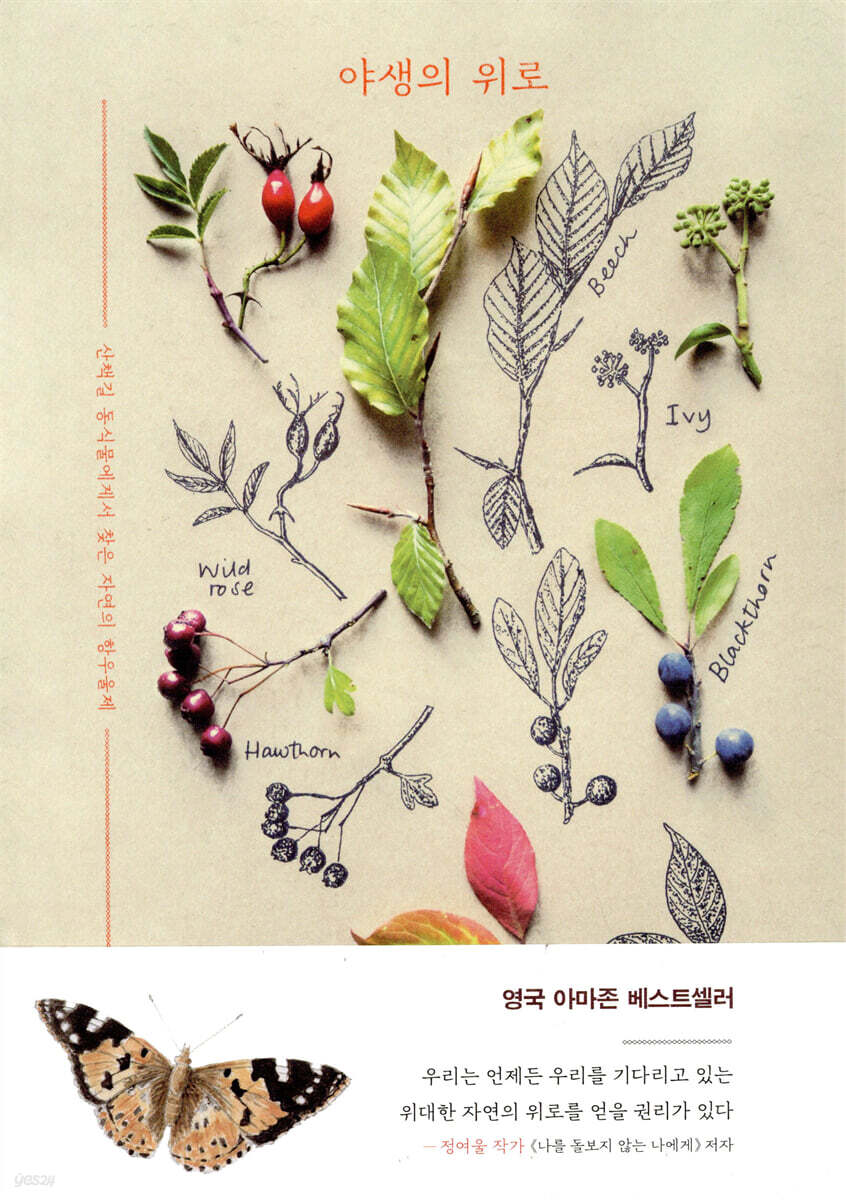

Mitchell experiences various aspects of depression, from mild lethargy to suicidal thoughts, and through vivid writing, drawings, and photographs, he captures the natural world that comforted him during these times.

The process of observing, sketching, and photographing flora and fauna on my daily walks gave me the mental strength to begin my journey of recovery even on the most difficult days.

Mitchell, a museum historian, designer, and illustrator, has poured his talents and knowledge into this book.

The photographs, sketches, and watercolors harmoniously arranged on each page of the book, along with the delicate sentences, allow the reader to fully enjoy the nature he saw, heard, and felt through the book.

Mitchell skillfully navigates between intimate psychology and natural landscapes, drawing on biochemical and neuroscience research to explain the healing power of nature on the mind and body.

Instead of trying to overcome his depression, Mitchell tries to live with it by comforting and soothing it.

In addition to antidepressants and counseling, we use the solace of nature in harmony to balance our turbulent minds.

For Mitchell, nature is a powerful force that inspires his will to live and prepares him for the next season.

After walking with Emma Mitchell, who finds joy in a single flower and is moved to tears by the sight of a swallow that has flown thousands of kilometers, you will learn to find joy in the green outside your window even on days when the storms of your heart are raging.

A book that lets you glimpse the spring outside without leaving the living room.

A memoir by a museum historian who suffered from depression for half his life.

A twelve-month record of flowers, plants, and animals that will build your mental strength for the next season.

“It’s definitely comforting to know that I can do something for myself, even on a gloomy day.”

Emma Mitchell suffered from depression for 25 years.

"The Consolation of the Wild" is a memoir about the depression he suffered from for half his life, and also a year-long diary about the solace he found in nature during several episodes of severe depression.

Mitchell experiences various aspects of depression, from mild lethargy to suicidal thoughts, and through vivid writing, drawings, and photographs, he captures the natural world that comforted him during these times.

The process of observing, sketching, and photographing flora and fauna on my daily walks gave me the mental strength to begin my journey of recovery even on the most difficult days.

Mitchell, a museum historian, designer, and illustrator, has poured his talents and knowledge into this book.

The photographs, sketches, and watercolors harmoniously arranged on each page of the book, along with the delicate sentences, allow the reader to fully enjoy the nature he saw, heard, and felt through the book.

Mitchell skillfully navigates between intimate psychology and natural landscapes, drawing on biochemical and neuroscience research to explain the healing power of nature on the mind and body.

Instead of trying to overcome his depression, Mitchell tries to live with it by comforting and soothing it.

In addition to antidepressants and counseling, we use the solace of nature in harmony to balance our turbulent minds.

For Mitchell, nature is a powerful force that inspires his will to live and prepares him for the next season.

After walking with Emma Mitchell, who finds joy in a single flower and is moved to tears by the sight of a swallow that has flown thousands of kilometers, you will learn to find joy in the green outside your window even on days when the storms of your heart are raging.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommendation

Preface _ Healing Methods Found in Forests and Gardens

OCTOBER · October _ Leaves cover the ground, and magpies migrate with the seasons.

NOVEMBER · November _ The sunlight fades and all colors fade

DECEMBER · December _ The shortest days of the year, the magpies gather

JANUARY · January _ Ladybugs Sleep and Snowdrop Buds Emerge

FEBRUARY · February _ The plum blossoms bloom and the first bees appear.

MARCH · March _ Hawthorn leaves sprout and prickly plum blossoms bloom

APRIL · April _ Forest windflowers are in full bloom and swallows are returning.

MAY · May _ Nightingales Sing and Daisy Flowers Bloom

JUNE · June _ Snake-eyed butterflies flit and honeybee orchids bloom

JULY · Wild carrots are in bloom and spotted moths are fluttering.

AUGUST · August _ The leaves of the sago palm are sprouting and the wild plums are ripening.

SEPTEMBER · September _ Blackberries ripen and swallows prepare to fly

Acknowledgements

Translator's Note: Intense Comfort Found in Ordinary Places

Names of creatures in this book

References

Preface _ Healing Methods Found in Forests and Gardens

OCTOBER · October _ Leaves cover the ground, and magpies migrate with the seasons.

NOVEMBER · November _ The sunlight fades and all colors fade

DECEMBER · December _ The shortest days of the year, the magpies gather

JANUARY · January _ Ladybugs Sleep and Snowdrop Buds Emerge

FEBRUARY · February _ The plum blossoms bloom and the first bees appear.

MARCH · March _ Hawthorn leaves sprout and prickly plum blossoms bloom

APRIL · April _ Forest windflowers are in full bloom and swallows are returning.

MAY · May _ Nightingales Sing and Daisy Flowers Bloom

JUNE · June _ Snake-eyed butterflies flit and honeybee orchids bloom

JULY · Wild carrots are in bloom and spotted moths are fluttering.

AUGUST · August _ The leaves of the sago palm are sprouting and the wild plums are ripening.

SEPTEMBER · September _ Blackberries ripen and swallows prepare to fly

Acknowledgements

Translator's Note: Intense Comfort Found in Ordinary Places

Names of creatures in this book

References

Detailed image

.jpg)

Into the book

When I get home, I spread out what I found on the beach today next to the shells and fossils I've collected so far.

When I lay out and examine the plants and fossils I've collected, my mind enters a state similar to when I'm painting or kneading bread.

Inner conflicts subside and peace sets in.

I create a small temporary museum by displaying items that I have chosen entirely for myself.

The process not only provides comfort and relieves depression, but also amplifies the satisfaction felt when finding these objects.

I am curious about the mental pathways associated with organizing and displaying things.

I wonder if it goes back to the process our ancestors used to process the leaves, berries, seeds, nuts and shellfish they picked up on their foraging trips.

Properly studying this link would require a significant budget and a small army of archaeologists and neuroscientists.

All I know is that the act of "knolling," of simply arranging things I've found, relieves stress and gives me a subtle sense of intoxication.

--- p.64

As I turn the corner, I see a barred owl flying slowly from the left side of the road.

I pull over to see the guy.

The guy who had been hovering in the sky for a while suddenly dives down between the long grass stalks.

(…) As the creature passes by, its small gray body and stubby tail caught in its claws catch my eye.

To be a field mouse.

I turn the car around and drive down the wide shoulder near the field where the owl has landed.

An owl sits with its shoulders hunched in a meadow hidden by a hedge.

Perhaps they are enjoying their meal in a secret place.

As the sun sinks below the horizon, owls nibble their prey, casting a golden halo over the trees and hedges.

It is one of the most beautiful sights I have ever seen in my life.

It strikes me that no matter how depressed I am, how deceived, helpless, and devastated I become, it is worth fighting on if I can just encounter this sight and fill my head with its healing effects.

--- p.111~112

For the past four months, while I've been scratching my head, I've managed to avoid it by spending time among the plants and wild animals.

I wandered through beaches and wetlands, forests and meadows, filling my eyes and heart with the proud flocks of starlings and the fresh green of vine shoots.

I went for walks regardless of the weather, and each step I took subtly adjusted the chemistry in my brain, helping me survive the winter.

(…) Controlling depression requires constant vigilance.

A walk in nature, a creative outlet, and a daily battle with the defensive weapon of a furry pumpkin friend to protect you when you're alone.

(…) I am exhausted and almost drained from fighting depression.

We need warm days and the sunshine of Fenland to gather strength.

--- p.115~116

Listening to the song of the blackbird, I am... ... yes, I am happy.

The lyrical and fleeting sound of a longing song sets off a dazzling firework of color in my head.

Everything is peaceful.

As I write this, the gloomy situation I described last month is over.

I feel an immense sense of relief, but I've been in this situation several times in my life.

It is as dark and deadly as an obsidian blade.

--- p.143

I read the research results from the University of Exeter.

It is said that having birds in the surrounding landscape is effective in alleviating depression.

In an attempt at ornithological self-healing, I decided to attract birds to our garden.

During my last depressive episode, I realized that focusing on small projects helped block out the automatic onslaught of crippling guilt and sadness.

(…) I buy myself a pretty birdcage as a gift.

(…) Over the next few days, a flock of sparrows became regular visitors, along with a magpie, a starling, a pair of goldfinch, and, happily, a few woodpeckers.

(…) It is thrilling to hear the high-pitched, sharp cries of the owls in our garden.

(…) I feel a surge of gratitude towards these little birds, and suddenly I feel a change in my heart.

It feels healing.

The thought of having a live bird feeder in my backyard effectively chases away the blues.

--- p.146~148

It's a cliché to compare someone who perseveres in a seemingly impossible task to a swallow, but the swallow's journey is truly remarkable.

Although several are killed by storms or predators along the way, most arrive safely, mate, lay eggs, and raise their young.

They will wander the fields all summer like swift, feathered arrows, then huddle together on the telephone wires, preparing for the next year's migration.

During the season when my condition is generally good, swallows stay in this area.

It gives me goosebumps to see that bird resting in our garden after its wonderful journey.

Just as the swallow reached its destination, I too survived another winter.

I sit in the courtyard and cry quietly for a while.

--- p.156

There is a plant behind the hill that I came to see.

These are bluebells at their peak.

The lower part of the stem is in full bloom with each petal facing outward, while the upper part is just about to open as a flower bud.

A deep, rich, and vivid blue color seems to sway and resonate with the flowers.

Among the bluebells are patches of ground covered with herbaceous berries, forest anemones and ground potato stems.

I sit there with my legs crossed and look at the bluebells.

Sunlight and abundant flowers fill the field of vision and reach the brain cells.

It's the same intense satisfaction that comes from eating the most delicious chocolate cake or a bowl of homemade salty potato chips.

It's as if my mind is devouring this sight and drawing nourishment from it.

--- p.167~168

Whenever I'm gripped by depression, I fight back with every weapon I have, barely managing to get out of it, slowly recover, and try to live my life again.

It's a vicious cycle that I can't escape, but I'm holding on strong even today.

(…) I know there is no way I can ever completely escape this state.

This disease has robbed me of the ability to fully enjoy life for more than half of my life.

(…) This disease sits on my mind like a giant gray slug, but I try to break free by striking at it whenever I can.

Spend some time among the birds and plants of the forest, give him a room, kick him, and create a more positive mental state with a distracting activity like drawing or making something with your hands.

See a therapist, take medication every day, and increase your dosage if you feel overwhelmed by depression.

(…) If I could just wake up one morning and purely enjoy what I do, if I could not lower my expectations of what I can do.

I cry out loud at the shore of Lake Reckford, listening to the beautiful song of a small, rare bird.

I just stand there and let the tears flow.

--- p.175~176

One summer I picked up a pebble with a curious pattern.

The pebbles had small, sharp, volcanic-like projections, similar to those on the surrounding rocks.

I liked the pebbles, so I put those in the bucket too.

As I was watching the shrimp and crabs wriggle in the little pool I had created, something moved very slightly and the pebbles seemed to shake slightly.

(…) Then the top of the small volcano opened wide like a trapdoor, and thin, pink, tassel-shaped tentacles suddenly popped out like palms.

The tentacles repeatedly skimmed the water above and then disappeared into the trapdoor all at once.

A scene similar to the one in "Life on Earth" was unfolding before my eyes, in the half-liter of seawater I was crouching on the sand and looking at.

It was the first time I'd ever had such a thrilling experience, except for riding a roller coaster at an amusement park.

(…) I witnessed a fascinating creature that acted regardless of my presence.

It was a touch of nature, a living, breathing trace of the wild within a brightly colored plastic bucket.

I felt ecstatic about that experience and wanted to have more similar experiences.

--- p.223~224

According to marine biologist Wallace Nichols, when you stand on the shore and look out over the ocean or watch a river flow by, your eyes and brain are distracted from visual stimulation.

It's a vacation for the brain, a respite from the hectic and constant stimulation that is inevitable in modern life, a kind of marine meditation.

I feel it clearly while I let my feet go with the current.

As the waves roll in and out, the mind drifts into a calm, still state.

It's a similar feeling to when I crochet or sketch.

The inner turmoil subsides and dark thoughts disappear.

--- p.229~230

Spending time in nature has healed my broken spirit this year.

On the darkest day of March, it was a soft green sapling on the roadside median that brought me back to my senses and stopped me from committing suicide.

The past twelve months have been difficult, surreal, and terrifying.

Most of the time my mind was in shreds, but whenever I felt like I was going to collapse, the sight of a bird or a short walk in the woods would help me escape the worst of my depression.

This fact gives me tremendous comfort.

Wild places are my essential medicine and safety net.

--- p.252

A year of experience using nature as a healing medicine convinced me that for human beings to be whole, they must be in a natural landscape.

Since the beginning of time, there has been a strong bond between humans and the earth.

We evolved to live in wild places.

The mental health problems of modern people may be due to their disconnection from nature.

The incidence of mental illness is increasing worldwide.

Because the reason is still unclear, all kinds of theories are running wild.

(…) But what is clear to me and to those who have studied this field is that disconnection from nature is a significant factor in the problem, independent of the influence of other factors.

--- p.253

When we leave our homes, offices, or urban environments and move into places with forests, greenery, and wildlife, a series of interconnected physiological and neurological changes occur within us.

Although the science behind this is still in its infancy, numerous studies have already confirmed that the beneficial effects of natural scenery can alleviate mental illness.

I know full well that the amazing effects I experienced may not be the same for everyone.

However, I hope that the idea of nature walks as a treatment for depression will become more widespread.

I hope that walking in nature will not be seen as an unusual or eccentric activity, but rather that the fundamental human need to spend time outdoors will be seen as an effective approach that complements conventional psychiatry and standard psychotherapy.

When I lay out and examine the plants and fossils I've collected, my mind enters a state similar to when I'm painting or kneading bread.

Inner conflicts subside and peace sets in.

I create a small temporary museum by displaying items that I have chosen entirely for myself.

The process not only provides comfort and relieves depression, but also amplifies the satisfaction felt when finding these objects.

I am curious about the mental pathways associated with organizing and displaying things.

I wonder if it goes back to the process our ancestors used to process the leaves, berries, seeds, nuts and shellfish they picked up on their foraging trips.

Properly studying this link would require a significant budget and a small army of archaeologists and neuroscientists.

All I know is that the act of "knolling," of simply arranging things I've found, relieves stress and gives me a subtle sense of intoxication.

--- p.64

As I turn the corner, I see a barred owl flying slowly from the left side of the road.

I pull over to see the guy.

The guy who had been hovering in the sky for a while suddenly dives down between the long grass stalks.

(…) As the creature passes by, its small gray body and stubby tail caught in its claws catch my eye.

To be a field mouse.

I turn the car around and drive down the wide shoulder near the field where the owl has landed.

An owl sits with its shoulders hunched in a meadow hidden by a hedge.

Perhaps they are enjoying their meal in a secret place.

As the sun sinks below the horizon, owls nibble their prey, casting a golden halo over the trees and hedges.

It is one of the most beautiful sights I have ever seen in my life.

It strikes me that no matter how depressed I am, how deceived, helpless, and devastated I become, it is worth fighting on if I can just encounter this sight and fill my head with its healing effects.

--- p.111~112

For the past four months, while I've been scratching my head, I've managed to avoid it by spending time among the plants and wild animals.

I wandered through beaches and wetlands, forests and meadows, filling my eyes and heart with the proud flocks of starlings and the fresh green of vine shoots.

I went for walks regardless of the weather, and each step I took subtly adjusted the chemistry in my brain, helping me survive the winter.

(…) Controlling depression requires constant vigilance.

A walk in nature, a creative outlet, and a daily battle with the defensive weapon of a furry pumpkin friend to protect you when you're alone.

(…) I am exhausted and almost drained from fighting depression.

We need warm days and the sunshine of Fenland to gather strength.

--- p.115~116

Listening to the song of the blackbird, I am... ... yes, I am happy.

The lyrical and fleeting sound of a longing song sets off a dazzling firework of color in my head.

Everything is peaceful.

As I write this, the gloomy situation I described last month is over.

I feel an immense sense of relief, but I've been in this situation several times in my life.

It is as dark and deadly as an obsidian blade.

--- p.143

I read the research results from the University of Exeter.

It is said that having birds in the surrounding landscape is effective in alleviating depression.

In an attempt at ornithological self-healing, I decided to attract birds to our garden.

During my last depressive episode, I realized that focusing on small projects helped block out the automatic onslaught of crippling guilt and sadness.

(…) I buy myself a pretty birdcage as a gift.

(…) Over the next few days, a flock of sparrows became regular visitors, along with a magpie, a starling, a pair of goldfinch, and, happily, a few woodpeckers.

(…) It is thrilling to hear the high-pitched, sharp cries of the owls in our garden.

(…) I feel a surge of gratitude towards these little birds, and suddenly I feel a change in my heart.

It feels healing.

The thought of having a live bird feeder in my backyard effectively chases away the blues.

--- p.146~148

It's a cliché to compare someone who perseveres in a seemingly impossible task to a swallow, but the swallow's journey is truly remarkable.

Although several are killed by storms or predators along the way, most arrive safely, mate, lay eggs, and raise their young.

They will wander the fields all summer like swift, feathered arrows, then huddle together on the telephone wires, preparing for the next year's migration.

During the season when my condition is generally good, swallows stay in this area.

It gives me goosebumps to see that bird resting in our garden after its wonderful journey.

Just as the swallow reached its destination, I too survived another winter.

I sit in the courtyard and cry quietly for a while.

--- p.156

There is a plant behind the hill that I came to see.

These are bluebells at their peak.

The lower part of the stem is in full bloom with each petal facing outward, while the upper part is just about to open as a flower bud.

A deep, rich, and vivid blue color seems to sway and resonate with the flowers.

Among the bluebells are patches of ground covered with herbaceous berries, forest anemones and ground potato stems.

I sit there with my legs crossed and look at the bluebells.

Sunlight and abundant flowers fill the field of vision and reach the brain cells.

It's the same intense satisfaction that comes from eating the most delicious chocolate cake or a bowl of homemade salty potato chips.

It's as if my mind is devouring this sight and drawing nourishment from it.

--- p.167~168

Whenever I'm gripped by depression, I fight back with every weapon I have, barely managing to get out of it, slowly recover, and try to live my life again.

It's a vicious cycle that I can't escape, but I'm holding on strong even today.

(…) I know there is no way I can ever completely escape this state.

This disease has robbed me of the ability to fully enjoy life for more than half of my life.

(…) This disease sits on my mind like a giant gray slug, but I try to break free by striking at it whenever I can.

Spend some time among the birds and plants of the forest, give him a room, kick him, and create a more positive mental state with a distracting activity like drawing or making something with your hands.

See a therapist, take medication every day, and increase your dosage if you feel overwhelmed by depression.

(…) If I could just wake up one morning and purely enjoy what I do, if I could not lower my expectations of what I can do.

I cry out loud at the shore of Lake Reckford, listening to the beautiful song of a small, rare bird.

I just stand there and let the tears flow.

--- p.175~176

One summer I picked up a pebble with a curious pattern.

The pebbles had small, sharp, volcanic-like projections, similar to those on the surrounding rocks.

I liked the pebbles, so I put those in the bucket too.

As I was watching the shrimp and crabs wriggle in the little pool I had created, something moved very slightly and the pebbles seemed to shake slightly.

(…) Then the top of the small volcano opened wide like a trapdoor, and thin, pink, tassel-shaped tentacles suddenly popped out like palms.

The tentacles repeatedly skimmed the water above and then disappeared into the trapdoor all at once.

A scene similar to the one in "Life on Earth" was unfolding before my eyes, in the half-liter of seawater I was crouching on the sand and looking at.

It was the first time I'd ever had such a thrilling experience, except for riding a roller coaster at an amusement park.

(…) I witnessed a fascinating creature that acted regardless of my presence.

It was a touch of nature, a living, breathing trace of the wild within a brightly colored plastic bucket.

I felt ecstatic about that experience and wanted to have more similar experiences.

--- p.223~224

According to marine biologist Wallace Nichols, when you stand on the shore and look out over the ocean or watch a river flow by, your eyes and brain are distracted from visual stimulation.

It's a vacation for the brain, a respite from the hectic and constant stimulation that is inevitable in modern life, a kind of marine meditation.

I feel it clearly while I let my feet go with the current.

As the waves roll in and out, the mind drifts into a calm, still state.

It's a similar feeling to when I crochet or sketch.

The inner turmoil subsides and dark thoughts disappear.

--- p.229~230

Spending time in nature has healed my broken spirit this year.

On the darkest day of March, it was a soft green sapling on the roadside median that brought me back to my senses and stopped me from committing suicide.

The past twelve months have been difficult, surreal, and terrifying.

Most of the time my mind was in shreds, but whenever I felt like I was going to collapse, the sight of a bird or a short walk in the woods would help me escape the worst of my depression.

This fact gives me tremendous comfort.

Wild places are my essential medicine and safety net.

--- p.252

A year of experience using nature as a healing medicine convinced me that for human beings to be whole, they must be in a natural landscape.

Since the beginning of time, there has been a strong bond between humans and the earth.

We evolved to live in wild places.

The mental health problems of modern people may be due to their disconnection from nature.

The incidence of mental illness is increasing worldwide.

Because the reason is still unclear, all kinds of theories are running wild.

(…) But what is clear to me and to those who have studied this field is that disconnection from nature is a significant factor in the problem, independent of the influence of other factors.

--- p.253

When we leave our homes, offices, or urban environments and move into places with forests, greenery, and wildlife, a series of interconnected physiological and neurological changes occur within us.

Although the science behind this is still in its infancy, numerous studies have already confirmed that the beneficial effects of natural scenery can alleviate mental illness.

I know full well that the amazing effects I experienced may not be the same for everyone.

However, I hope that the idea of nature walks as a treatment for depression will become more widespread.

I hope that walking in nature will not be seen as an unusual or eccentric activity, but rather that the fundamental human need to spend time outdoors will be seen as an effective approach that complements conventional psychiatry and standard psychotherapy.

--- p.254

Publisher's Review

“What caught me on the verge of suicide was

“It was a sapling with a soft green tint that was on the road median.”

On a spring day in March, when sunlight and new buds are bursting with life, Emma Mitchell finds herself caught in a whirlpool of overwhelming self-loathing.

All sorts of irrational but completely uncontrollable thoughts and criticisms burst out like an explosion.

It is the most overwhelming weapon in the arsenal of depression.

He is mired in bitter self-criticism, constantly ruminating on past failures and hurtful memories.

Old memories cut through my heart like a well-honed blade.

Eventually, he is driven by depression and staggers towards self-destruction.

What Mitchell experienced that day was the borderline of depression, the "black hole of depression," where the symptoms become so stubborn that they become unbearable.

He drives out onto the road, feeling intense fear and unbearable helplessness.

My mind is filled with terrifying thoughts about where I can most effectively die.

Just when it feels like nothing but despair and death remains, Mitchell discovers a small sapling growing on the roadside divider.

The light green leaves passing before his eyes catch his eye.

The early spring sunshine and fresh green leaves calm the storm of emotions that are rushing towards death.

A part of your mind that you thought was gone with him, a part of your brain that seeks healing from nature, awakens.

“Trees… green, comforting.” After running along the saplings for a while longer, Mitchell stops his reckless drive towards destruction and returns home.

Ask your family for help, see your doctor to develop a recovery plan, get plenty of rest, and increase your antidepressant dosage.

Thus, Mitchell turns from the brink of suicide and begins his journey of recovery from the depression that has engulfed him.

The solace of nature, which had always helped him avoid the worst symptoms of depression, once again saved Mitchell's life. (pp. 133-135)

A memoir of half a lifetime of depression and a year-long nature observation diary

“It’s definitely comforting to know that I can do something for myself, even on a gloomy day.”

Emma Mitchell suffered from depression for 25 years.

『The Wild Remedy (original title: The Wild Remedy, published by Simsim)』 is a memoir about the depression he suffered from for half his life, and also a year-long diary about the solace he found in nature during several episodes of severe depression.

The journey, which begins in autumn, endures winter, passes through the budding spring and the hot summer, and returns to autumn again, captures not only the changes of nature and the seasons, but also the emotional changes he experiences.

Mitchell begins by taking a walk through the woods near his home with his dog, Annie, and visits various places, including a beach with childhood memories, a cliff with old fossils, and a hill with small orchids.

Not only exploring the space, but also drawing, photographing, and collecting natural objects found during walks becomes part of the healing process.

What is particularly impressive is the seamless connection between the depiction of nature and the depiction of psychology.

Mitchell, a naturalist, designer, and illustrator who studies flora, fauna, minerals, and geology, fully displays his talents and knowledge in this book.

The photographs, sketches, and watercolors harmoniously arranged on each page of the book, along with the flowing sentences, help readers fully enjoy the nature he saw, heard, and felt through the book.

This book, which is packed with “The Power of Nature to Heal the Soul (231 pages)” collected while walking through the forest every season, becomes a forest filled with the nature outside the door and its healing effects.

Literary critic Emma Freud described it as a "literary antidepressant" made of paper and ink.

A simple sketch of a dandelion, a watercolor painting of a sagebrush, or making a collection of plants you can easily find can be as calming as the walk itself.

Trying to approximate the appearance of a falcon with a pencil can help dispel complex and dark thoughts in your mind, just as much as meeting the bird that inspired you to do so.

The calm process of looking at the subject and drawing it is much more important than the perfect result.

The beneficial effects of nature observation and the time spent recording what you see create a kind of synergy effect.

(…) When I spend time in the woods or gardens and notice the fine details of the plants and wildlife that live there, I feel my depression lift.

This became a form of self-healing for me. (p. 24)

A powerful way to build mental strength for the next season.

Nature can be an effective health model that complements medical psychotherapy.

Mitchell's experience of finding solace in nature and healing his troubled heart is not unique.

We've all probably had the experience of feeling relaxed and our negative thoughts melting away after a walk in nature and observing butterflies or birds.

Many people willingly take the time to go outdoors to see cherry blossoms in spring, the ocean in summer, autumn leaves in fall, and snow-covered fields in winter.

But is there any scientific basis for the positive emotions evoked by nature? Does a stroll through the park or a gaze at the gently raked edges of a pebble on the beach actually have a measurable healing effect on our bodies and brains?

Many researchers have studied the positive effects of nature on humans.

Among them, clinical pathologist Margaret Hansen extensively collected and analyzed 10 years of research exploring the relationship between nature and human mental health in her paper, “Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy.”

Through this, Hansen confirmed the clinical therapeutic effects of nature, and based on these results, he actively recommends that medical professionals use forest bathing as a model for promoting universal health.

One example of a clinical health method that utilizes nature is the UK's 'Nature's Way', a social prescription program linked to the Eden Project, the world's largest greenhouse.

Social prescribing is a different concept from pharmaceutical prescribing, and is where medical professionals suggest various non-clinical services that patients need.

Nature's Way, heavily supported by the UK Department for Health and Social Care, provides people with the opportunity to improve their health and well-being by prescribing nature walks.

Patients are prescribed activities, such as 'weekly gardening', by their medical staff to improve their physical and mental health.

Launched in 2016, the programme has already transformed hundreds of lives and significantly reduced the burden on the UK's National Health Service by significantly reducing hospital stays.

What's most encouraging is that these outdoor activities boost patients' creativity and help them form new relationships, improving their overall well-being and depressive symptoms.

Nature's Way empowers people to experience the healing power of nature by spending time in nature, and has become a part of their daily lives, with participants saying it has become an important part of their lives and mental health.

Promotes the secretion of serotonin, dopamine, and endorphins…

The power of nature to relieve stress and anxiety and boost immunity.

“A walk in the garden is like reaching into nature’s invisible medicine cabinet.”

The emotional transformation experienced by those who participated in Nature's Way demonstrates that nature's healing power is universally effective for humans.

When we breathe a sigh of relief in the presence of nature, it is not simply because we like the beautiful scenery, but because a biological response actually occurs.

To explain these physical reactions, Mitchell cites biochemical and neuroscience research on the effects of nature on the human mind and body, and links the emotional changes experienced while walking in the woods, on the beach, or in the park to brain chemistry and hormonal fluctuations.

And based on this, I say that walking and observing wildlife can be powerful allies in the daily battle against the depression that sometimes strikes.

Research on the influence of nature on the human mind and body cited in this book

1.

Reduces stress and mental fatigue, and increases immunity and resilience.

Emma Mitchell takes daily walks in the woods near her home, observing the wildlife and plants, and feels her daily worries melt away and the veil of depression lift.

He finds the basis for this mood swing in the act of looking at nature and walking through the forest.

According to a study titled “Health effects of viewing landscapes,” conducted by Maria Velarde, a spatial experimental scientist at the University of Madrid, and the Norwegian School of Life Sciences, encountering natural landscapes can relieve stress and mental fatigue and even speed up recovery from illness.

Long-term improvements in people's overall health were also observed.

[Bio Science] published 'Dose of neighborhood nature: The Benefits for Mental Health of Living with Nature', which reported that the presence of plants has a greater impact, especially on people living in cities.

The same study found that spending time in nature reduced residents' depression, anxiety, and perceived stress, and that spending time outdoors alleviated mood swings (p. 18).

Additionally, the 'phytoncide' that we inhale while walking acts on the human immune system, endocrine system, circulatory system, and nervous system, preventing infection by viruses and bacteria.

While we spend time in nature, we unconsciously inhale phytoncides produced by plants, literally ‘disinfecting’ our bodies.

Mitchell often feels a strong sense of satisfaction when he sits in the grass and is surrounded by plants.

That comfort will soon heal his heart and become the nourishment that will sustain him for the coming tomorrow.

“The languid buzzing of solitary bees, collecting nectar and pollen from bluebells, can be heard.

I want to lie down among the flowers and take a nap.

Spend time comfortably.

This is forest bathing.

I am completely absorbed in the surrounding scenery.

I can smell the musty smell of fallen leaves and the subtle fragrance of bluebells.

The sunlight warms the back of my neck.

You can hear the busy rustling of small mammals in the bushes and the singing of birds overhead.

The forest lowers my blood pressure, lifts my mood, and reduces my stress levels.

“There is no doubt that this very moment is beneficial to my recovery.” (pp. 167-168)

2.

A natural antidepressant that promotes serotonin production

Serotonin is a hormone that projects widely throughout the central nervous system and influences biological functions, and important areas where serotonin is involved include circuits involved in mood and emotion.

Although the relationship between serotonin function and depression is not yet clearly understood, numerous studies have shown that changes in serotonin levels in the body affect not only depression but also aggression, impulsivity, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and suicidal thoughts.

Taking a walk in nature helps increase serotonin levels in a number of ways.

Human skin has a unique serotonin system that produces serotonin, so when sunlight hits the retina or skin, serotonin secretion increases and the resulting mood-boosting effect occurs.

It is because of this effect of sunlight that psychotherapists often recommend that people who complain of lethargy and depression go outside, get some sunlight, and go for a walk.

Additionally, British scientists have discovered that bacteria found in soil act in the body in a similar way to antidepressants.

When humans come into contact with benign soil bacteria such as Mycobacterium vacuole, proteins from the bacteria's cell walls increase serotonin secretion in specific brain cell populations.

This tells us that the time we spend weeding and tending plants isn't just beneficial for the flowers and trees in our flowerbeds. (pp. 19-20)

“Although recovery is slow, the healing effects of time spent among plants, whether wild or cultivated, are evident.

On clear mornings, I weed my flower beds, hoping that the contact with beneficial soil bacteria, particularly Mycobacterium vaccae and other as-yet-unidentified strains, will help balance my brain's neurotransmitters.

Gardening is like yoga in the dirt, so it's satisfying and subtly soothing, and it can even help banish depressive thoughts.

“It’s like observing the birds that come to the garden.” (pp. 154-155)

3.

"Foraging Rapture" Activates the Dopamine Reward System

When you go for a walk and encounter a new environment, the brain releases a neurotransmitter called dopamine, which gives you a temporary feeling of excitement.

This is what is called “gathering ecstasy.”

Dopamine, released from the brain's reward center, gives a feeling of accomplishment and pleasure.

These hormonal changes stem from the dopamine reward system that humans developed 200,000 years ago when they were hunter-gatherers.

Fruit-laden trees and berry bushes would have increased our ancestors' caloric intake, so having a positive reflex toward edible plants was a survival necessity.

Thus, collecting plants stimulated the reward mechanism in the brain, and this became a habit.

These biological processes, which occur through contact with nature, reinforce reward-driven behaviors by adjusting the chemical balance in the brain and creating feelings of satisfaction, which in turn encourages us to get out into the woods and reap the benefits of a walk.

The dopamine released during a walk stimulates other beneficial activities, so a virtuous cycle begins, as walking through the forest helps the brain recover from depression. (pp. 35-37)

“As my mind calms down from the new thrill, I realize that the baby's breath, mingling with thyme and fairy flax, grows in clumps for several meters in all directions.

It is about 7 centimeters tall, and has inner petals that are as thin as a peacock's tail feathers, inside which are blue like a crocus and clear like the Caribbean sky.

(…) Although the vegetation of this area is mostly made up of small plants, it brings great joy.

“It feels like my brain is flooded with dopamine, but I keep exploring because I know there’s still more ecstasy waiting.” (p. 187)

The clinical healing effects of nature experienced firsthand while walking through the forest

Walking, knitting, sketching, collecting nature objects, even bird seed storage…

Instead of trying to overcome his depression, Mitchell tries to live with it by comforting and soothing it.

He regularly receives counseling and takes antidepressants to avoid falling into serious depression, and he also tries various methods to relieve depression recommended by specialists and researchers.

Taking daily walks in the forest, knitting gloves for my daughter, drawing the plants and animals I observe, and bringing birds into the garden are all part of this effort.

Instead of relying solely on conventional medical prescriptions like antidepressants or counseling, or believing that nature is a panacea, we use complementary therapies and nature to balance our turbulent minds.

Mitchell says that controlling depression requires a constant “daily battle with nature walks, creative time, and the defensive arsenal of a furry pumpkin friend to keep you company when you’re alone” (p. 116).

He never gives up on taking care of himself, struggling with the never-ending depression that comes crashing in like waves even when it seems to have subsided.

Emma Mitchell marvels at the traces of distant fossils and is moved to tears by the sight of swallows flying thousands of kilometers to welcome spring.

Witnessing these moments of nature boosted his will to live and gave him the strength to continue living.

As you follow Mitchell and listen to the techniques and knowledge he generously shares, you will naturally discover how to discover immense beauty in everyday nature.

After reading this book, you will learn how to find hope and joy in the leaves outside your window, even when you are overcome by overwhelming self-loathing and piercing thoughts, and how nature can help you overcome depression.

“The fragrant smell of dried coastal grasses, the soft pink of Armeria flowers blooming on the cliffs, the movement of small fish, the seawater pooling in hollowed-out rock holes eroded by the waves, the pungent smell of drying seaweed, and the tiny green starfish held preciously in the palm of my hand like an emerald.

“The desire to experience again the intense joy I felt when I first encountered nature on the beach at Malos and in my grandfather’s garden kept me going.” (p. 233)

Spring has come, but it's hard to go outside.

Mitchell says his hope is that “when you feel helpless, unable to leave the sofa or bed, and stuck in a morass of bitter sadness, you will find solace in reading my observations in this book, looking at the photographs and drawings, and even going out to find a snail or a weasel yourself (p. 25).”

While reading this book, which fully conveys the joy of encountering nature through delicate brushstrokes and vivid images, you will feel the comfort of the wild, the sprouting buds, and the approaching spring at your fingertips.

In this way, you will be able to embrace the spring outside your door with all your might, even though it is right next to you.

“It was a sapling with a soft green tint that was on the road median.”

On a spring day in March, when sunlight and new buds are bursting with life, Emma Mitchell finds herself caught in a whirlpool of overwhelming self-loathing.

All sorts of irrational but completely uncontrollable thoughts and criticisms burst out like an explosion.

It is the most overwhelming weapon in the arsenal of depression.

He is mired in bitter self-criticism, constantly ruminating on past failures and hurtful memories.

Old memories cut through my heart like a well-honed blade.

Eventually, he is driven by depression and staggers towards self-destruction.

What Mitchell experienced that day was the borderline of depression, the "black hole of depression," where the symptoms become so stubborn that they become unbearable.

He drives out onto the road, feeling intense fear and unbearable helplessness.

My mind is filled with terrifying thoughts about where I can most effectively die.

Just when it feels like nothing but despair and death remains, Mitchell discovers a small sapling growing on the roadside divider.

The light green leaves passing before his eyes catch his eye.

The early spring sunshine and fresh green leaves calm the storm of emotions that are rushing towards death.

A part of your mind that you thought was gone with him, a part of your brain that seeks healing from nature, awakens.

“Trees… green, comforting.” After running along the saplings for a while longer, Mitchell stops his reckless drive towards destruction and returns home.

Ask your family for help, see your doctor to develop a recovery plan, get plenty of rest, and increase your antidepressant dosage.

Thus, Mitchell turns from the brink of suicide and begins his journey of recovery from the depression that has engulfed him.

The solace of nature, which had always helped him avoid the worst symptoms of depression, once again saved Mitchell's life. (pp. 133-135)

A memoir of half a lifetime of depression and a year-long nature observation diary

“It’s definitely comforting to know that I can do something for myself, even on a gloomy day.”

Emma Mitchell suffered from depression for 25 years.

『The Wild Remedy (original title: The Wild Remedy, published by Simsim)』 is a memoir about the depression he suffered from for half his life, and also a year-long diary about the solace he found in nature during several episodes of severe depression.

The journey, which begins in autumn, endures winter, passes through the budding spring and the hot summer, and returns to autumn again, captures not only the changes of nature and the seasons, but also the emotional changes he experiences.

Mitchell begins by taking a walk through the woods near his home with his dog, Annie, and visits various places, including a beach with childhood memories, a cliff with old fossils, and a hill with small orchids.

Not only exploring the space, but also drawing, photographing, and collecting natural objects found during walks becomes part of the healing process.

What is particularly impressive is the seamless connection between the depiction of nature and the depiction of psychology.

Mitchell, a naturalist, designer, and illustrator who studies flora, fauna, minerals, and geology, fully displays his talents and knowledge in this book.

The photographs, sketches, and watercolors harmoniously arranged on each page of the book, along with the flowing sentences, help readers fully enjoy the nature he saw, heard, and felt through the book.

This book, which is packed with “The Power of Nature to Heal the Soul (231 pages)” collected while walking through the forest every season, becomes a forest filled with the nature outside the door and its healing effects.

Literary critic Emma Freud described it as a "literary antidepressant" made of paper and ink.

A simple sketch of a dandelion, a watercolor painting of a sagebrush, or making a collection of plants you can easily find can be as calming as the walk itself.

Trying to approximate the appearance of a falcon with a pencil can help dispel complex and dark thoughts in your mind, just as much as meeting the bird that inspired you to do so.

The calm process of looking at the subject and drawing it is much more important than the perfect result.

The beneficial effects of nature observation and the time spent recording what you see create a kind of synergy effect.

(…) When I spend time in the woods or gardens and notice the fine details of the plants and wildlife that live there, I feel my depression lift.

This became a form of self-healing for me. (p. 24)

A powerful way to build mental strength for the next season.

Nature can be an effective health model that complements medical psychotherapy.

Mitchell's experience of finding solace in nature and healing his troubled heart is not unique.

We've all probably had the experience of feeling relaxed and our negative thoughts melting away after a walk in nature and observing butterflies or birds.

Many people willingly take the time to go outdoors to see cherry blossoms in spring, the ocean in summer, autumn leaves in fall, and snow-covered fields in winter.

But is there any scientific basis for the positive emotions evoked by nature? Does a stroll through the park or a gaze at the gently raked edges of a pebble on the beach actually have a measurable healing effect on our bodies and brains?

Many researchers have studied the positive effects of nature on humans.

Among them, clinical pathologist Margaret Hansen extensively collected and analyzed 10 years of research exploring the relationship between nature and human mental health in her paper, “Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy.”

Through this, Hansen confirmed the clinical therapeutic effects of nature, and based on these results, he actively recommends that medical professionals use forest bathing as a model for promoting universal health.

One example of a clinical health method that utilizes nature is the UK's 'Nature's Way', a social prescription program linked to the Eden Project, the world's largest greenhouse.

Social prescribing is a different concept from pharmaceutical prescribing, and is where medical professionals suggest various non-clinical services that patients need.

Nature's Way, heavily supported by the UK Department for Health and Social Care, provides people with the opportunity to improve their health and well-being by prescribing nature walks.

Patients are prescribed activities, such as 'weekly gardening', by their medical staff to improve their physical and mental health.

Launched in 2016, the programme has already transformed hundreds of lives and significantly reduced the burden on the UK's National Health Service by significantly reducing hospital stays.

What's most encouraging is that these outdoor activities boost patients' creativity and help them form new relationships, improving their overall well-being and depressive symptoms.

Nature's Way empowers people to experience the healing power of nature by spending time in nature, and has become a part of their daily lives, with participants saying it has become an important part of their lives and mental health.

Promotes the secretion of serotonin, dopamine, and endorphins…

The power of nature to relieve stress and anxiety and boost immunity.

“A walk in the garden is like reaching into nature’s invisible medicine cabinet.”

The emotional transformation experienced by those who participated in Nature's Way demonstrates that nature's healing power is universally effective for humans.

When we breathe a sigh of relief in the presence of nature, it is not simply because we like the beautiful scenery, but because a biological response actually occurs.

To explain these physical reactions, Mitchell cites biochemical and neuroscience research on the effects of nature on the human mind and body, and links the emotional changes experienced while walking in the woods, on the beach, or in the park to brain chemistry and hormonal fluctuations.

And based on this, I say that walking and observing wildlife can be powerful allies in the daily battle against the depression that sometimes strikes.

Research on the influence of nature on the human mind and body cited in this book

1.

Reduces stress and mental fatigue, and increases immunity and resilience.

Emma Mitchell takes daily walks in the woods near her home, observing the wildlife and plants, and feels her daily worries melt away and the veil of depression lift.

He finds the basis for this mood swing in the act of looking at nature and walking through the forest.

According to a study titled “Health effects of viewing landscapes,” conducted by Maria Velarde, a spatial experimental scientist at the University of Madrid, and the Norwegian School of Life Sciences, encountering natural landscapes can relieve stress and mental fatigue and even speed up recovery from illness.

Long-term improvements in people's overall health were also observed.

[Bio Science] published 'Dose of neighborhood nature: The Benefits for Mental Health of Living with Nature', which reported that the presence of plants has a greater impact, especially on people living in cities.

The same study found that spending time in nature reduced residents' depression, anxiety, and perceived stress, and that spending time outdoors alleviated mood swings (p. 18).

Additionally, the 'phytoncide' that we inhale while walking acts on the human immune system, endocrine system, circulatory system, and nervous system, preventing infection by viruses and bacteria.

While we spend time in nature, we unconsciously inhale phytoncides produced by plants, literally ‘disinfecting’ our bodies.

Mitchell often feels a strong sense of satisfaction when he sits in the grass and is surrounded by plants.

That comfort will soon heal his heart and become the nourishment that will sustain him for the coming tomorrow.

“The languid buzzing of solitary bees, collecting nectar and pollen from bluebells, can be heard.

I want to lie down among the flowers and take a nap.

Spend time comfortably.

This is forest bathing.

I am completely absorbed in the surrounding scenery.

I can smell the musty smell of fallen leaves and the subtle fragrance of bluebells.

The sunlight warms the back of my neck.

You can hear the busy rustling of small mammals in the bushes and the singing of birds overhead.

The forest lowers my blood pressure, lifts my mood, and reduces my stress levels.

“There is no doubt that this very moment is beneficial to my recovery.” (pp. 167-168)

2.

A natural antidepressant that promotes serotonin production

Serotonin is a hormone that projects widely throughout the central nervous system and influences biological functions, and important areas where serotonin is involved include circuits involved in mood and emotion.

Although the relationship between serotonin function and depression is not yet clearly understood, numerous studies have shown that changes in serotonin levels in the body affect not only depression but also aggression, impulsivity, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and suicidal thoughts.

Taking a walk in nature helps increase serotonin levels in a number of ways.

Human skin has a unique serotonin system that produces serotonin, so when sunlight hits the retina or skin, serotonin secretion increases and the resulting mood-boosting effect occurs.

It is because of this effect of sunlight that psychotherapists often recommend that people who complain of lethargy and depression go outside, get some sunlight, and go for a walk.

Additionally, British scientists have discovered that bacteria found in soil act in the body in a similar way to antidepressants.

When humans come into contact with benign soil bacteria such as Mycobacterium vacuole, proteins from the bacteria's cell walls increase serotonin secretion in specific brain cell populations.

This tells us that the time we spend weeding and tending plants isn't just beneficial for the flowers and trees in our flowerbeds. (pp. 19-20)

“Although recovery is slow, the healing effects of time spent among plants, whether wild or cultivated, are evident.

On clear mornings, I weed my flower beds, hoping that the contact with beneficial soil bacteria, particularly Mycobacterium vaccae and other as-yet-unidentified strains, will help balance my brain's neurotransmitters.

Gardening is like yoga in the dirt, so it's satisfying and subtly soothing, and it can even help banish depressive thoughts.

“It’s like observing the birds that come to the garden.” (pp. 154-155)

3.

"Foraging Rapture" Activates the Dopamine Reward System

When you go for a walk and encounter a new environment, the brain releases a neurotransmitter called dopamine, which gives you a temporary feeling of excitement.

This is what is called “gathering ecstasy.”

Dopamine, released from the brain's reward center, gives a feeling of accomplishment and pleasure.

These hormonal changes stem from the dopamine reward system that humans developed 200,000 years ago when they were hunter-gatherers.

Fruit-laden trees and berry bushes would have increased our ancestors' caloric intake, so having a positive reflex toward edible plants was a survival necessity.

Thus, collecting plants stimulated the reward mechanism in the brain, and this became a habit.

These biological processes, which occur through contact with nature, reinforce reward-driven behaviors by adjusting the chemical balance in the brain and creating feelings of satisfaction, which in turn encourages us to get out into the woods and reap the benefits of a walk.

The dopamine released during a walk stimulates other beneficial activities, so a virtuous cycle begins, as walking through the forest helps the brain recover from depression. (pp. 35-37)

“As my mind calms down from the new thrill, I realize that the baby's breath, mingling with thyme and fairy flax, grows in clumps for several meters in all directions.

It is about 7 centimeters tall, and has inner petals that are as thin as a peacock's tail feathers, inside which are blue like a crocus and clear like the Caribbean sky.

(…) Although the vegetation of this area is mostly made up of small plants, it brings great joy.

“It feels like my brain is flooded with dopamine, but I keep exploring because I know there’s still more ecstasy waiting.” (p. 187)

The clinical healing effects of nature experienced firsthand while walking through the forest

Walking, knitting, sketching, collecting nature objects, even bird seed storage…

Instead of trying to overcome his depression, Mitchell tries to live with it by comforting and soothing it.

He regularly receives counseling and takes antidepressants to avoid falling into serious depression, and he also tries various methods to relieve depression recommended by specialists and researchers.

Taking daily walks in the forest, knitting gloves for my daughter, drawing the plants and animals I observe, and bringing birds into the garden are all part of this effort.

Instead of relying solely on conventional medical prescriptions like antidepressants or counseling, or believing that nature is a panacea, we use complementary therapies and nature to balance our turbulent minds.

Mitchell says that controlling depression requires a constant “daily battle with nature walks, creative time, and the defensive arsenal of a furry pumpkin friend to keep you company when you’re alone” (p. 116).

He never gives up on taking care of himself, struggling with the never-ending depression that comes crashing in like waves even when it seems to have subsided.

Emma Mitchell marvels at the traces of distant fossils and is moved to tears by the sight of swallows flying thousands of kilometers to welcome spring.

Witnessing these moments of nature boosted his will to live and gave him the strength to continue living.

As you follow Mitchell and listen to the techniques and knowledge he generously shares, you will naturally discover how to discover immense beauty in everyday nature.

After reading this book, you will learn how to find hope and joy in the leaves outside your window, even when you are overcome by overwhelming self-loathing and piercing thoughts, and how nature can help you overcome depression.

“The fragrant smell of dried coastal grasses, the soft pink of Armeria flowers blooming on the cliffs, the movement of small fish, the seawater pooling in hollowed-out rock holes eroded by the waves, the pungent smell of drying seaweed, and the tiny green starfish held preciously in the palm of my hand like an emerald.

“The desire to experience again the intense joy I felt when I first encountered nature on the beach at Malos and in my grandfather’s garden kept me going.” (p. 233)

Spring has come, but it's hard to go outside.

Mitchell says his hope is that “when you feel helpless, unable to leave the sofa or bed, and stuck in a morass of bitter sadness, you will find solace in reading my observations in this book, looking at the photographs and drawings, and even going out to find a snail or a weasel yourself (p. 25).”

While reading this book, which fully conveys the joy of encountering nature through delicate brushstrokes and vivid images, you will feel the comfort of the wild, the sprouting buds, and the approaching spring at your fingertips.

In this way, you will be able to embrace the spring outside your door with all your might, even though it is right next to you.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: March 20, 2020

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 272 pages | 618g | 147*210*20mm

- ISBN13: 9791156758174

- ISBN10: 1156758173

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)