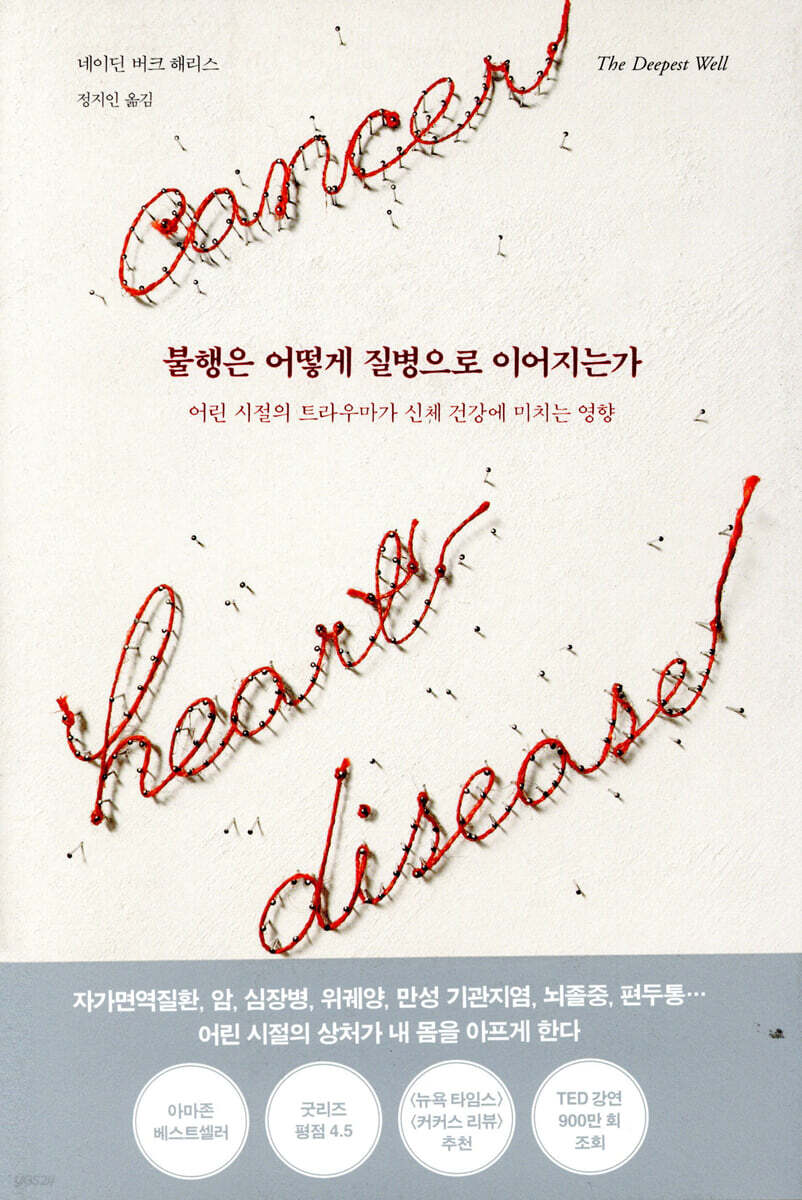

How Misfortune Leads to Disease

|

Description

Book Introduction

Amazon Bestseller! Goodreads Rating: 4.5!

Recommended by the New York Times and Kirkus Reviews! 9 million TED talks!

Autoimmune diseases, cancer, heart disease, stomach ulcers, chronic bronchitis, stroke, migraines…

Childhood wounds hurt my body

Many people recognize that trauma affects mental health.

Moreover, we usually find the cause of disease in our personal bad lifestyle habits, such as 'smoking a lot', 'drinking a lot of alcohol', 'eating a lot of salty and fatty foods', or 'not exercising'.

However, research conducted over the past two decades in scientific fields such as biology, immunology, clinical medicine, and social epidemiology has yielded very different results.

Severe and repetitive stress experienced during childhood has been shown to have a significant impact on physical health, including autoimmune diseases, obesity, heart disease, and shortened life expectancy.

Nadine Burke Harris, a pediatrician and public health expert, opened her clinic in 2007 in Hunters Point, a poor neighborhood in Bayview, San Francisco.

And there, I met countless young patients who came to my clinic with unusual symptoms.

From children who struggled with severe growth retardation because they couldn't gain weight to those whose asthma flared up every time their father slammed the wall, Harris witnessed firsthand how the trauma inflicted on children by abuse, neglect, parental alcohol and drug addiction, mental illness, and divorce manifested itself in devastating physical ailments.

Meeting children who struggle to recover with conventional treatments, Harris begins to wonder if negative childhood experiences can have profound effects not only on mental health but also on the immune system and brain development, ultimately impacting physical health.

"How Unhappiness Leads to Illness" is a book written by a physician and public health expert who, over the past decade, has sought to answer questions surrounding physical health and mental suffering that were previously difficult to understand, using the latest scientific research to find substantive evidence and clinically confirm ways to reduce the impact of negative childhood experiences.

Drawing on his clinical experience and knowledge, Harris provides insightful answers to questions such as why childhood trauma occurs, why exposure to stress in childhood can lead to health problems in middle age and retirement, what effective treatments are available, and what we can do to protect our health and that of our children.

Recommended by the New York Times and Kirkus Reviews! 9 million TED talks!

Autoimmune diseases, cancer, heart disease, stomach ulcers, chronic bronchitis, stroke, migraines…

Childhood wounds hurt my body

Many people recognize that trauma affects mental health.

Moreover, we usually find the cause of disease in our personal bad lifestyle habits, such as 'smoking a lot', 'drinking a lot of alcohol', 'eating a lot of salty and fatty foods', or 'not exercising'.

However, research conducted over the past two decades in scientific fields such as biology, immunology, clinical medicine, and social epidemiology has yielded very different results.

Severe and repetitive stress experienced during childhood has been shown to have a significant impact on physical health, including autoimmune diseases, obesity, heart disease, and shortened life expectancy.

Nadine Burke Harris, a pediatrician and public health expert, opened her clinic in 2007 in Hunters Point, a poor neighborhood in Bayview, San Francisco.

And there, I met countless young patients who came to my clinic with unusual symptoms.

From children who struggled with severe growth retardation because they couldn't gain weight to those whose asthma flared up every time their father slammed the wall, Harris witnessed firsthand how the trauma inflicted on children by abuse, neglect, parental alcohol and drug addiction, mental illness, and divorce manifested itself in devastating physical ailments.

Meeting children who struggle to recover with conventional treatments, Harris begins to wonder if negative childhood experiences can have profound effects not only on mental health but also on the immune system and brain development, ultimately impacting physical health.

"How Unhappiness Leads to Illness" is a book written by a physician and public health expert who, over the past decade, has sought to answer questions surrounding physical health and mental suffering that were previously difficult to understand, using the latest scientific research to find substantive evidence and clinically confirm ways to reduce the impact of negative childhood experiences.

Drawing on his clinical experience and knowledge, Harris provides insightful answers to questions such as why childhood trauma occurs, why exposure to stress in childhood can lead to health problems in middle age and retirement, what effective treatments are available, and what we can do to protect our health and that of our children.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommendation

Prologue | A Story Everyone Thought They Knew, But No One Did

Part 1 discovered

1 Something just isn't right

2 Go back to move forward

3 18 kilograms?

Part 2 Diagnosis

4 Attack of a giant bear encountered in the forest

5 Immune System at Risk

6 Mother rats who don't lick their pups

3-part prescription

Get out of 7 ACE

8 unanimous votes in favor

9 It's never too late to heal

10 “Mom, we have to get out of here.”

Part 4 Revolution

11 People who only look at their own suffering

12 The moment when the hidden world is revealed

13 I needed help

Epilogue | Those things are no longer passed down.

Acknowledgements

Appendix 1 | What is my ACE score?

Appendix 2 | Children's Wellness Center ACE Questionnaire

Huzhou

Prologue | A Story Everyone Thought They Knew, But No One Did

Part 1 discovered

1 Something just isn't right

2 Go back to move forward

3 18 kilograms?

Part 2 Diagnosis

4 Attack of a giant bear encountered in the forest

5 Immune System at Risk

6 Mother rats who don't lick their pups

3-part prescription

Get out of 7 ACE

8 unanimous votes in favor

9 It's never too late to heal

10 “Mom, we have to get out of here.”

Part 4 Revolution

11 People who only look at their own suffering

12 The moment when the hidden world is revealed

13 I needed help

Epilogue | Those things are no longer passed down.

Acknowledgements

Appendix 1 | What is my ACE score?

Appendix 2 | Children's Wellness Center ACE Questionnaire

Huzhou

Into the book

The factors that increased Evan's risk of waking up with half his body paralyzed and a host of other conditions are not uncommon.

About two-thirds of the American population is exposed to it, and it's so common that it's often overlooked.

What could be the factor? Lead? Asbestos? Hazardous substances used in packaging? No, it's the negative experiences we had as children.

--- p.17

Medical research over the past two decades has shown that childhood adversity literally imprints itself on us, transforming us, and the changes it creates within us may persist for decades.

Misfortune can disrupt a child's developmental trajectory and even affect their physiological functions.

It can also trigger chronic inflammation and hormonal changes that can be lifelong. It can also alter the way DNA is read and cells replicate, dramatically increasing the risk of heart disease, stroke, cancer, diabetes, and even Alzheimer's.

--- p.19

As in Diego's case, for most patients, ADHD symptoms do not appear out of nowhere.

Symptoms were most frequent in patients who had experienced some form of trauma or disruption to their lives.

For example, the twins who failed several classes and fought at school after witnessing an attempted murder in their home, or the triplets whose parents' divorce was so violent and acrimonious that the court ordered the Bayview Police Department to drop off and pick up the children instead of the mother and father.

--- p.31

As pioneers of public health, we were just beginning to take root, so we focused on the most exciting part of the well case: the part where Snow dispelled the long-term theory.

But I also learned an even bigger lesson.

If 100 people all drank from the same well and 98 of them got diarrhea, you could keep prescribing antibiotics, but you might also pause and ask, "What on earth is in this well?"

--- p.43~44

To better understand the potential link between abuse and obesity, Feliti began asking about childhood sexual abuse experiences during routine screenings and patient interviews in obesity programs.

The results were shocking.

One in two people admitted to such a past.

At first, Felicity thought this couldn't be true.

If it were true, I would have learned about that relationship in medical school.

But after talking to a total of 186 patients, he was convinced.

To be sure that the results weren't due to something peculiar about his patient population or his questioning style, he and five colleagues surveyed 100 other obese patients about their experiences of abuse.

When the same results came back, Feliti knew they had uncovered something incredible.

--- p.83~84

Using data from health screenings and questionnaires, Feliti and Anda found that risky behaviors and health status were correlated with the ACE index.

First, they realized that negative childhood experiences are surprisingly common.

Of the total population, 67 percent had at least one ACE category, and 12.6 percent had four or more.

Second, they found a dose-response relationship between negative childhood experiences and poor health outcomes.

This means that the higher the ACE index, the greater the health risk.

For example, people with four or more ACE categories were twice as likely to develop heart disease and cancer and 3.5 times as likely to develop chronic obstructive pulmonary disease compared to people with an ACE score of 0.

--- p.88

Of the people who participated in the original ACE study, 70 percent were Caucasian, or white, and 70 percent had a college education.

Moreover, the participants were patients at Kaiser Medical Center and received excellent medical services.

Subsequent ACE studies have continued to confirm the original findings. Many other studies, inspired by the ACE study, have clearly shown that adverse childhood experiences are a risk factor for many of the most common and serious illnesses in the United States (and globally), regardless of income, race, or access to healthcare.

--- p.90

There was no doubt that Diego was experiencing a toxic stress response.

This is because Diego's family has been through a number of hardships that have put an undue strain on his stress response system, including the sexual abuse he suffered when he was four years old.

My father had a clear drinking problem, and my mother suffered from depression.

Neither of them was able to relieve Diego's stress.

The combination of symptoms Diego was experiencing was entirely consistent with what is known to happen when the stress response system is activated for long periods of time without adequate support.

--- p.119

Children are particularly sensitive to repetitive stress responses.

High-intensity adversity affects not only the structure and function of the brain, but also the developing immune and hormonal systems, and even the way DNA is read and transcribed.

Once the stress response system is wired into a dysregulated pattern, its biological effects spread and cause problems throughout the body's internal organs.

The body is like a large, delicate Swiss watch, and what happens in the immune system is deeply connected to what happens in the cardiovascular system.

--- p.120

When the body's stress response system is continually overloaded, the sensitivity of dopamine receptors becomes disrupted.

Even if you want to feel the same level of pleasure as before, you will need more and more stimulation.

When biological changes in the ventral tegmental area cause cravings for dopamine stimulants like high-sugar, high-fat foods, these changes can also lead to increased risky behaviors. The ACE study demonstrated a dose-response relationship between exposure to adverse childhood experiences and the use of many activities and substances that activate the ventral tegmental area. Compared to those with an ACE score of 0, individuals with an ACE score of 4 or higher were 2.5 times more likely to smoke, 5.5 times more likely to be alcohol dependent, and 10 times more likely to use intravenous drugs.

So, if we want to prevent young people from becoming dependent on harmful dopamine stimulants like tobacco and alcohol, we must understand how experiencing adversity early in life affects dopamine function in the brain.

--- p.143

In the years since the ACE study was first published, scientists have been closely examining the link between adverse childhood experiences and autoimmune diseases.

Research findings show that childhood stress is strongly correlated with autoimmune diseases in both children and adults.

Public health scientist Shanta Dube collaborated with Drs. Feliti and Anda to analyze data from more than 15,000 ACE study participants.

They looked at their ACE index and how often they were hospitalized for autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, type 1 diabetes, celiac disease, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

What Dube found was shocking: People with an ACE score of 2 or higher were more than twice as likely to be hospitalized for an autoimmune disease as those with a score of 0.

--- p.150

In addition to showing that not licking their pups enough can have negative effects on their mothers, Minnie's research also showed how more licking can be beneficial.

Since the environment is something we can change, this meant there was still a lot of hope for babies born to mothers who "licked less."

The child is neither defective nor flawed.

Biology tells us that if a child receives safe, stable, and warm care early in life, they can develop a healthy stress response system in adulthood.

--- p.170

Just as babies with phenylketonuria are not born with any outward signs of the genetic disorder, children who come to our clinic don't come wearing a name tag that says, "I suffer from toxic stress."

That is precisely why it should be a universal screening test, not just a screening test.

I always remember the lesson that Guthrie taught the world.

Although there are simple ways to prevent it, you shouldn't wait until your child has symptoms of nerve damage to come to you.

--- p.262

Neuroscience research over the past few decades has shed light on why adverse experiences in early life can profoundly impact children's development.

The fetal and early childhood periods are a 'critical and sensitive period' for development and are also times of special opportunity.

A critical period is a time during development when irreversible changes occur depending on the presence or absence of a specific experience.

--- p.273

Another point I emphasized was that adults with a high ACE score are at higher risk for health problems, so it's important to ensure your doctor is aware of the ACE study. A doctor who is aware of the study can help patients understand how their ACE score and family history affect their risk for certain conditions, and they can work with patients to identify and prevent those conditions early.

--- p.318

Toxic stress is what happens when your stress response goes awry.

This is not an economic problem, a regional problem, or a personality problem; it is a biological mechanism.

So now we can see each other from a different perspective than before.

This means that we can see people having different experiences that trigger the same physiological response.

We can remove the blame and shame and address this issue in the same way we address any other health issue: as an indiscriminate public health crisis, like the flu or Zika virus.

--- p.324

Toxic stress is still in its infancy compared to childhood cancer.

We are just beginning to address this issue.

If the global crisis of childhood adversity were a book, we'd be in chapter two.

And in many ways, this book is about the story of that first chapter: the discovery of the biological mechanisms of childhood adversity.

We haven't perfected that approach yet, but we're working towards that goal.

--- p.388

Understanding that many of the problems plaguing our society stem from negative childhood experiences makes sense as a solution to efforts to reduce the negative experiences children experience and enhance the buffering capacity of their caregivers.

From there, we can continue to move on to the next step.

By interpreting that information, we can create more effective educational curricula, develop blood tests that can identify biomarkers of toxic stress, and then from there, we can develop broader solutions and innovations to reduce the harm of toxic stress, little by little, then in strides.

About two-thirds of the American population is exposed to it, and it's so common that it's often overlooked.

What could be the factor? Lead? Asbestos? Hazardous substances used in packaging? No, it's the negative experiences we had as children.

--- p.17

Medical research over the past two decades has shown that childhood adversity literally imprints itself on us, transforming us, and the changes it creates within us may persist for decades.

Misfortune can disrupt a child's developmental trajectory and even affect their physiological functions.

It can also trigger chronic inflammation and hormonal changes that can be lifelong. It can also alter the way DNA is read and cells replicate, dramatically increasing the risk of heart disease, stroke, cancer, diabetes, and even Alzheimer's.

--- p.19

As in Diego's case, for most patients, ADHD symptoms do not appear out of nowhere.

Symptoms were most frequent in patients who had experienced some form of trauma or disruption to their lives.

For example, the twins who failed several classes and fought at school after witnessing an attempted murder in their home, or the triplets whose parents' divorce was so violent and acrimonious that the court ordered the Bayview Police Department to drop off and pick up the children instead of the mother and father.

--- p.31

As pioneers of public health, we were just beginning to take root, so we focused on the most exciting part of the well case: the part where Snow dispelled the long-term theory.

But I also learned an even bigger lesson.

If 100 people all drank from the same well and 98 of them got diarrhea, you could keep prescribing antibiotics, but you might also pause and ask, "What on earth is in this well?"

--- p.43~44

To better understand the potential link between abuse and obesity, Feliti began asking about childhood sexual abuse experiences during routine screenings and patient interviews in obesity programs.

The results were shocking.

One in two people admitted to such a past.

At first, Felicity thought this couldn't be true.

If it were true, I would have learned about that relationship in medical school.

But after talking to a total of 186 patients, he was convinced.

To be sure that the results weren't due to something peculiar about his patient population or his questioning style, he and five colleagues surveyed 100 other obese patients about their experiences of abuse.

When the same results came back, Feliti knew they had uncovered something incredible.

--- p.83~84

Using data from health screenings and questionnaires, Feliti and Anda found that risky behaviors and health status were correlated with the ACE index.

First, they realized that negative childhood experiences are surprisingly common.

Of the total population, 67 percent had at least one ACE category, and 12.6 percent had four or more.

Second, they found a dose-response relationship between negative childhood experiences and poor health outcomes.

This means that the higher the ACE index, the greater the health risk.

For example, people with four or more ACE categories were twice as likely to develop heart disease and cancer and 3.5 times as likely to develop chronic obstructive pulmonary disease compared to people with an ACE score of 0.

--- p.88

Of the people who participated in the original ACE study, 70 percent were Caucasian, or white, and 70 percent had a college education.

Moreover, the participants were patients at Kaiser Medical Center and received excellent medical services.

Subsequent ACE studies have continued to confirm the original findings. Many other studies, inspired by the ACE study, have clearly shown that adverse childhood experiences are a risk factor for many of the most common and serious illnesses in the United States (and globally), regardless of income, race, or access to healthcare.

--- p.90

There was no doubt that Diego was experiencing a toxic stress response.

This is because Diego's family has been through a number of hardships that have put an undue strain on his stress response system, including the sexual abuse he suffered when he was four years old.

My father had a clear drinking problem, and my mother suffered from depression.

Neither of them was able to relieve Diego's stress.

The combination of symptoms Diego was experiencing was entirely consistent with what is known to happen when the stress response system is activated for long periods of time without adequate support.

--- p.119

Children are particularly sensitive to repetitive stress responses.

High-intensity adversity affects not only the structure and function of the brain, but also the developing immune and hormonal systems, and even the way DNA is read and transcribed.

Once the stress response system is wired into a dysregulated pattern, its biological effects spread and cause problems throughout the body's internal organs.

The body is like a large, delicate Swiss watch, and what happens in the immune system is deeply connected to what happens in the cardiovascular system.

--- p.120

When the body's stress response system is continually overloaded, the sensitivity of dopamine receptors becomes disrupted.

Even if you want to feel the same level of pleasure as before, you will need more and more stimulation.

When biological changes in the ventral tegmental area cause cravings for dopamine stimulants like high-sugar, high-fat foods, these changes can also lead to increased risky behaviors. The ACE study demonstrated a dose-response relationship between exposure to adverse childhood experiences and the use of many activities and substances that activate the ventral tegmental area. Compared to those with an ACE score of 0, individuals with an ACE score of 4 or higher were 2.5 times more likely to smoke, 5.5 times more likely to be alcohol dependent, and 10 times more likely to use intravenous drugs.

So, if we want to prevent young people from becoming dependent on harmful dopamine stimulants like tobacco and alcohol, we must understand how experiencing adversity early in life affects dopamine function in the brain.

--- p.143

In the years since the ACE study was first published, scientists have been closely examining the link between adverse childhood experiences and autoimmune diseases.

Research findings show that childhood stress is strongly correlated with autoimmune diseases in both children and adults.

Public health scientist Shanta Dube collaborated with Drs. Feliti and Anda to analyze data from more than 15,000 ACE study participants.

They looked at their ACE index and how often they were hospitalized for autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, type 1 diabetes, celiac disease, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

What Dube found was shocking: People with an ACE score of 2 or higher were more than twice as likely to be hospitalized for an autoimmune disease as those with a score of 0.

--- p.150

In addition to showing that not licking their pups enough can have negative effects on their mothers, Minnie's research also showed how more licking can be beneficial.

Since the environment is something we can change, this meant there was still a lot of hope for babies born to mothers who "licked less."

The child is neither defective nor flawed.

Biology tells us that if a child receives safe, stable, and warm care early in life, they can develop a healthy stress response system in adulthood.

--- p.170

Just as babies with phenylketonuria are not born with any outward signs of the genetic disorder, children who come to our clinic don't come wearing a name tag that says, "I suffer from toxic stress."

That is precisely why it should be a universal screening test, not just a screening test.

I always remember the lesson that Guthrie taught the world.

Although there are simple ways to prevent it, you shouldn't wait until your child has symptoms of nerve damage to come to you.

--- p.262

Neuroscience research over the past few decades has shed light on why adverse experiences in early life can profoundly impact children's development.

The fetal and early childhood periods are a 'critical and sensitive period' for development and are also times of special opportunity.

A critical period is a time during development when irreversible changes occur depending on the presence or absence of a specific experience.

--- p.273

Another point I emphasized was that adults with a high ACE score are at higher risk for health problems, so it's important to ensure your doctor is aware of the ACE study. A doctor who is aware of the study can help patients understand how their ACE score and family history affect their risk for certain conditions, and they can work with patients to identify and prevent those conditions early.

--- p.318

Toxic stress is what happens when your stress response goes awry.

This is not an economic problem, a regional problem, or a personality problem; it is a biological mechanism.

So now we can see each other from a different perspective than before.

This means that we can see people having different experiences that trigger the same physiological response.

We can remove the blame and shame and address this issue in the same way we address any other health issue: as an indiscriminate public health crisis, like the flu or Zika virus.

--- p.324

Toxic stress is still in its infancy compared to childhood cancer.

We are just beginning to address this issue.

If the global crisis of childhood adversity were a book, we'd be in chapter two.

And in many ways, this book is about the story of that first chapter: the discovery of the biological mechanisms of childhood adversity.

We haven't perfected that approach yet, but we're working towards that goal.

--- p.388

Understanding that many of the problems plaguing our society stem from negative childhood experiences makes sense as a solution to efforts to reduce the negative experiences children experience and enhance the buffering capacity of their caregivers.

From there, we can continue to move on to the next step.

By interpreting that information, we can create more effective educational curricula, develop blood tests that can identify biomarkers of toxic stress, and then from there, we can develop broader solutions and innovations to reduce the harm of toxic stress, little by little, then in strides.

--- p.394

Publisher's Review

“This new science is a surprising twist on a story we thought we knew well.”

Autoimmune diseases, cancer, heart disease, stomach ulcers, chronic bronchitis, stroke, migraines…

Childhood wounds hurt my body

At 5 o'clock one Saturday morning, a forty-three-year-old man woke up.

He rolls out of bed without thinking and tries to go to the bathroom.

But I can't roll my body to the side, and my right arm feels paralyzed.

At that very moment, he realizes that it is not just his right limb that is paralyzed.

The entire right side of the body, including the face, was paralyzed.

He was immediately taken to the emergency room, where the medical staff asked him questions to confirm his medical history.

The wife tells them something she thinks might be relevant to the situation.

I usually enjoy exercising, and my recent health checkup showed that everything was fine.

Soon, doctors will make a preliminary judgment on him.

“Stroke emergency patient.

“43-year-old male, non-smoker, no risk factors.”

Unknown to him, his wife, or even his doctors, he had one major risk factor.

That's a factor that doubles his chances of having a stroke.

It's not uncommon for him to wake up half-paralyzed and to have a number of other conditions that increase his risk.

A common factor that affects approximately two-thirds of the American population is negative childhood experiences (pp. 16-17).

Many people recognize that trauma affects mental health.

Moreover, we usually find the cause of disease in our personal bad lifestyle habits, such as 'smoking a lot', 'drinking a lot of alcohol', 'eating a lot of salty and fatty foods', or 'not exercising'.

However, research conducted over the past two decades in scientific fields such as biology, immunology, clinical medicine, and social epidemiology has yielded very different results.

Severe and repetitive stress experienced during childhood has been shown to have a significant impact on physical health, including autoimmune diseases, obesity, heart disease, and shortened life expectancy.

Nadin Burk Harris, a pediatrician and public health expert, opened her clinic in 2007 in Hunters Point, a poor neighborhood in Bayview, San Francisco.

And there, I met countless young patients who came to my clinic with unusual symptoms.

From children who struggled with severe growth retardation because they couldn't gain weight to those whose asthma flared up every time their father slammed the wall, Harris witnessed firsthand how the trauma inflicted on children by abuse, neglect, parental alcohol and drug addiction, mental illness, and divorce manifested itself in devastating physical ailments.

Meeting children who struggle to recover with conventional treatments, Harris begins to wonder if negative childhood experiences can have profound effects not only on mental health but also on the immune system and brain development, ultimately impacting physical health.

『How Unhappiness Leads to Illness (Original title: The Deepest Well, published by Simsim)』 is a book about the process in which the author, a doctor and public health expert, sought practical evidence based on the latest scientific research to solve questions surrounding physical health and mental suffering that were difficult to understand over the past 10 years, and confirmed in clinical practice ways to reduce the impact of negative childhood experiences.

Drawing on his clinical experience and knowledge, Harris provides insightful answers to questions such as why childhood trauma occurs, why exposure to stress in childhood can lead to health problems in middle age and retirement, what effective treatments are available, and what we can do to protect our health and that of our children.

A doctor's life changed by a child who would never grow up again.

A large-scale epidemiological study of 17,421 people reveals the surprising truth about childhood trauma.

Among the many children Harris met in his clinic, there was one who completely changed his life as a doctor.

Diego, a child of Mexican immigrant descent, came to the clinic with suspicion of ADHD due to several behavioral problems at school.

In addition to his poor impulse control, Diego also suffered from chronic asthma and eczema.

But the biggest problem Harris discovered was Diego's height.

Seven-year-old Diego was not just shorter than his peers, but also very short, about the average height for a four-year-old. (p. 28)

While reviewing Diego's health and upbringing, Harris learned that the boy had been sexually abused by his parents and a close friend as a child, and that since then, his behavior had been suggestive of ADHD and his health had deteriorated significantly.

If only a few children had suffered overwhelming hardship and suffered ill health, it might have been a coincidence, but Diego was a poster child for the hundreds of children Harris had met. (p. 34) The suffering of these children, living in a place where social resources are scarce and poverty and violence are the norm, was palpable.

While Harris was looking into Diego's stunted growth, he came across a paper that raised the possibility that there might be a biological link between childhood adversity and impaired health.

In 1998, the American Journal of Preventative Medicine published a paper titled “Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study” (hereafter, the ACE Study), written by internist Vincent Felitt and epidemiologist Robert Anda.

This study is the first to examine the relationship between high-intensity stress from childhood adversity and poor health, using a survey of 17,421 adults and multiple interviews. (p. 75) The specific findings presented in the paper are as follows:

First, negative childhood experiences are surprisingly common.

Sixty-seven percent of the population had at least one negative experience, and 12.6 percent had four or more.

Second, there is a dose-response relationship between negative childhood experiences and poor health.

In other words, the more negative experiences you have, the greater the risk to your health.

People who had experienced four or more of these conditions were twice as likely to develop heart disease and cancer and 3.5 times as likely to develop chronic obstructive pulmonary disease compared to those who had not experienced them (p. 88).

This paper objectively demonstrated the link between childhood trauma and physical health, something Harris had never heard of during his medical studies.

Harris felt as if all the questions he had been holding onto had been answered at once.

Despite using the best treatment methods, his children's health remained stagnant. He was increasingly seeing the connection between unhappiness and health problems, but he was at a loss as to how to resolve the issue. The ACE research paper opened a new path for him.

And from then on, Harris's life takes a rapid turn toward a larger sea.

He decided to help the young patients who came to him and find practical ways to relieve them of the suffering they would face in the future.

Constant and repetitive stress affects the nervous, immune, and hormonal systems.

The relationship between disease and unhappiness revealed through cutting-edge science, including brain science, neuroscience, immunology, and clinical medicine.

It is widely known through numerous studies and books that trauma is etched in the body and has long-lasting emotional and psychological effects.

The book goes a step further, saying that persistent, repetitive stress, which is difficult for children to handle, affects not only the nervous system but also the immune, hormonal, and cardiovascular systems, causing lifelong health problems.

And this is clearly proven by mobilizing the latest science, including brain science, neuroscience, immunology, and clinical medicine.

When our bodies sense danger, they trigger violent chemical reactions to protect themselves.

And most importantly, your body remembers.

The stress response system is a miraculous product of evolution that has allowed humanity to survive and thrive to this day.

We all have a stress response system that is finely tuned by genetics and early life experiences and is highly individualized. (p. 106)

The problem is that when the stress response is activated too often or the stressor is too intense, our body's stress thermostat breaks down.

When a certain temperature is reached, the supply of 'heat' should be cut off, but what happens is that the body continues to pour cortisol (a hormone that helps the body adapt to repeated or long-term stressors) throughout the body's system. (p. 116) So it is dangerous for a child to be exposed to toxic stress, that is, strong, frequent, and long-lasting negative experiences such as physical and emotional abuse, neglect, substance abuse or mental illness of a caregiver, violence, or severe financial hardship.

In addition, the effects of toxic stress are more severe if a child exposed to it does not receive appropriate adult support at the appropriate time. (p. 118) Diego was also experiencing toxic stress reactions, and his family members had their own problems and were unable to alleviate his stress.

The combination of symptoms Diego experienced was what happens when the stress response system is activated for long periods of time without proper support.

“Children are particularly sensitive to repetitive stress responses.

High-intensity adversity affects not only the structure and function of the brain, but also the developing immune and hormonal systems, and even the way DNA is read and transcribed.

Once the stress response system is wired into a dysregulated pattern, its biological effects spread and cause problems throughout the body's internal organs.

“The body is like a large, delicate Swiss watch; what happens in the immune system is deeply connected to what happens in the cardiovascular system.” (p. 120)

Harris found that the more negative childhood experiences a person has, the more frequently and intensely their stress response system reacts to multiple stressors.

And it explains in detail how our body responds to stress based on the nervous, hormonal, and immune systems.

The direct effects of adverse childhood experiences on our bodies

1.

The nervous system - the front line of efficiently processing information for survival.

Among the brain regions, the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and noradrenergic nucleus in the locus coeruleus are at the forefront of the stress response.

That's why we suffer the most from stress responses that deviate severely from the norm, and for a long period of time, and as a result, the way we work also fundamentally changes.

The authors focus particularly on the ventral tegmental area (VTA) in understanding how negative childhood experiences lead to long-term problems.

This is the pleasure and reward center, which influences behavior and addiction.

“When the body’s stress response system is continually overloaded, the sensitivity of dopamine receptors becomes disrupted.

Even if you want to feel the same level of pleasure as before, you will need more and more stimulation.

When biological changes in the ventral tegmental area cause cravings for dopamine stimulants like high-sugar, high-fat foods, these changes can also lead to increased risky behaviors. The ACE study demonstrated a dose-response relationship between exposure to adverse childhood experiences and the use of many activities and substances that activate the ventral tegmental area. Compared to those with an ACE score of 0, individuals with an ACE score of 4 or higher were 2.5 times more likely to smoke, 5.5 times more likely to be alcohol dependent, and 10 times more likely to use intravenous drugs.

“Therefore, if we want to prevent young people from becoming dependent on harmful dopamine stimulants like tobacco and alcohol, we must understand how experiencing adversity early in life affects dopamine function in the brain.” (p. 143)

2.

The hormonal system - the area most sensitive to stress responses

Almost everything in our body's hormonal system is affected by stress.

Growth hormone, sex hormones such as estrogen and testosterone, thyroid hormones, and insulin, which regulates blood sugar, all generally decrease in amount during times of stress.

Among the major health effects are dysfunction of the ovaries and testes (also known as the gonads), growth arrest, and obesity.

"We have children with ACE scores of 0, even though they live in the same neighborhood, have the same access to health care, and have the same lack of safe play areas and nutritious food. When we understand the hormonal impact of toxic stress on the hormonal systems of children with high ACE scores, we realize that their overweight isn't solely due to a diet of fast food.

It's not just that we live in food deserts (a general term for neighborhoods lacking nutritious food) and are being raised by parents who think Taco Bell is a healthy alternative to McDonald's.

While these things certainly play a part in exacerbating the problem, they don't tell the whole story.

Our study data demonstrate how powerful the mechanisms underlying toxic stress can be.

In other words, the ambassador's abnormality was also an important cause.

If you grow up in a food desert, it's obviously difficult to be healthy.

“But if your cortisol levels are high and you can’t resist cravings for high-sugar, high-fat foods, it will be even harder to choose broccoli over French fries.” (p. 147)

3.

Immune system - an organ that develops in response to the environment

Just as a baby's brain and nervous system are not fully developed at birth, the immune system continues to develop long after birth.

A baby's immune system develops in response to the environment it encounters over the first few years of life.

When stress response regulation becomes dysregulated, immune and inflammatory responses take a serious hit, because stress hormones affect virtually every component of the immune system.

Studies have shown that dysregulating the stress response increases inflammation, hypersensitivity, and even autoimmune diseases like Graves' disease.

While many people believe these conditions are caused by genetic misfortune, the following research shows that environmental and specific factors, such as childhood adversity, are strongly correlated with autoimmune diseases.

“In the years since the ACE study was first published, scientists have been closely examining the link between adverse childhood experiences and autoimmune diseases.

Research findings show that childhood stress is strongly correlated with autoimmune diseases in both children and adults.

Public health scientist Shanta Dube collaborated with Drs. Feliti and Anda to analyze data from more than 15,000 ACE study participants.

They looked at their ACE index and how often they were hospitalized for autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, type 1 diabetes, celiac disease, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

What Dube discovered was shocking: “People with an ACE score of 2 or higher were more than twice as likely to be hospitalized for autoimmune disease compared to those with a score of 0.” (p. 150)

Whether poor or rich, white or black, negative childhood experiences

It makes us sick silently and fatally by itself.

After analyzing numerous ACE studies, Harris became convinced that identifying people exposed to toxic stress beforehand would not only allow for earlier detection of related conditions but also increase the likelihood of more effective treatment.

Moreover, it was thought that by treating damaged stress response systems, it might even be possible to prevent future diseases.

So he sought out people more powerful and influential than himself to inform them about his negative childhood experiences and find ways to address them.

Then, Harris attended a gathering of highly successful women in San Francisco.

The attendees were all white and comprised of San Francisco's upper-class: lawyers, angel investors, consulting professionals, and successful tech entrepreneurs.

He asked attendees to share their thoughts on how to educate people about ACEs and the importance of screening for toxic stress early.

Surprisingly, half of the ten people who attended the meeting shared their past experiences related to negative childhood experiences (p. 300).

Their pasts, which poured out like a flood, were very similar to what Harris had heard from his own patients: parental mental illness, addiction problems, sexual assault, physical or emotional abuse, domestic violence.

Caroline, who has achieved great success in the IT field, carefully shared her story, showing how a family can be torn apart by negative childhood experiences. (p. 302) Caroline suffered from frequent marital fights and panic disorder due to her husband's inability to control his anger and his tendency to treat her as a possession.

And the young son, who had endured his parents' fights by crying, was exposed to psychological trauma and was diagnosed with ADHD.

After struggling for several years, Caroline was able to break free from the tunnel of pain by ending her marriage and receiving psychotherapy with her son, following her son's courageous words that "we must get out of this terrible situation."

Harris knew that statistically, many people around him had experienced adverse childhood experiences, but this was the first time he had had such an open conversation about these experiences outside of a clinic.

“I say this often, half jokingly.

The biggest difference between Bayview and Pacific Heights is that in Bayview, everyone knows who the uncle who molested you is.

This is not because there are no people in the Pacific Heights area, zip code 94115, who could harm a child, or people with drug addictions or mental illnesses.

“It’s just that people there don’t talk about such things.” (p. 323)

This case shatters the stigma that adverse childhood experiences only affect people from poor communities or people of color, including Black people.

In the ACE study by Feliti and Anda, which provided strong scientific inspiration to Harris, 70 percent of those who had adverse childhood experiences were white and had graduated from college.

But many people try to ignore this, further reinforcing prejudice against the poor and people of color.

Harris, in particular, saw firsthand through this encounter how toxic stress, when fed by concealment and shame, can spiral out of control.

There are concerns that solutions that target only specific communities will not make much progress in solving the problem.

Toxic stress is a story about basic human biology, and negative experiences are a universal problem that occurs everywhere, regardless of race or geography.

That's why, he says, to combat toxic stress, we need to let go of the shame of revealing our pain and blaming certain groups.

That means we need to approach it in the same way we approach solving health problems like the flu or pandemics, based on science.

Prevention is as important as treatment.

How to Prevent Toxic Stress from a Public Health Perspective

This book not only warns of the dangers of the negative effects of childhood stress, but also suggests ways to reduce its impact.

Harris offers six proven strategies to address the effects of toxic stress in clinical settings.

These are getting enough sleep, taking care of your mental health, maintaining healthy relationships, regular exercise, a balanced diet, and mindfulness.

The six elements aim to mitigate the adverse effects of toxic stress on the nervous, endocrine, and immune systems, as previously mentioned.

These six elements are areas where parents and those experiencing toxic stress can clearly see significant benefits if they pay attention and pay attention to them.

But Harris says this isn't enough.

Prevention is more important than treatment.

In particular, he says that problems should be discovered and resolved earlier because the development of the nervous, endocrine, and immune systems during childhood is extremely important in a child's life.

Harris strongly argues that the Toxic Stress Test (ACE test) should be added to the basic tests that measure the health and development of young children (e.g., jaundice test, inborn errors of metabolism test, hearing loss test, etc.) (The ACE test questionnaire that Harris actually used in the medical field is included in the appendix of this book, so that anyone can check their ACE status.)

Furthermore, it is emphasized that efforts at the social and national levels are urgently needed to conduct this test at the level of public health as a whole, rather than at the level of individual hospitals, and to jointly find and implement effective treatments.

One of the representative examples in the field of public health is the story of the well.

In late August 1854, a severe cholera outbreak occurred in London.

The outbreaks were all concentrated around communal wells, but the report states that when the pump handles were removed to make the wells unusable, the outbreaks subsided.

Harris mentions this case, saying, “If 100 people all drank from the same well and 98 of them got diarrhea, you could keep prescribing antibiotics, but you might also pause and ask, ‘What the hell is in this well?’” (p. 44).

Harris believed that prescribing medications to children who came to his clinic without even examining them with a stethoscope was no different from indiscriminately prescribing antibiotics to the patients in the well case.

Rather than rushing to prescribe the medicine that was right in front of him, Harris spent over a decade painstakingly researching what was in the wells children were drinking from, and discovered that they were all linked to toxic stress.

This is why the original title of this book, which emphasizes the importance of prevention rather than simple treatment, is 『The Deepest Well』.

Childhood misfortune is a problem that cannot be solved through the efforts of individuals and families alone.

Another point this book emphasizes is that the family, surrounding environment, and social system surrounding an individual affect that person's health.

Children are infinitely vulnerable and society is ignorant of their suffering.

That is the harsh reality that not only American society but also Korean society faces.

Because everyone only sees their own suffering, the negative influences children receive from their parents and surroundings are often easily ignored.

This is why we only pay brief attention to the issue of child abuse, which often appears in the news.

The various cases contained in this book are not just the sad stories of someone in a faraway land, but could be my own story.

Harris's extensive scientific evidence and diverse case studies will help us understand the problems we face and work together to find solutions.

By caring for children exposed to toxic stress in all the spaces where they grow up—home, community, school—and letting adult victims know, "It's not your fault," we can help our society's Diegos recover and continue to lead healthy lives.

Autoimmune diseases, cancer, heart disease, stomach ulcers, chronic bronchitis, stroke, migraines…

Childhood wounds hurt my body

At 5 o'clock one Saturday morning, a forty-three-year-old man woke up.

He rolls out of bed without thinking and tries to go to the bathroom.

But I can't roll my body to the side, and my right arm feels paralyzed.

At that very moment, he realizes that it is not just his right limb that is paralyzed.

The entire right side of the body, including the face, was paralyzed.

He was immediately taken to the emergency room, where the medical staff asked him questions to confirm his medical history.

The wife tells them something she thinks might be relevant to the situation.

I usually enjoy exercising, and my recent health checkup showed that everything was fine.

Soon, doctors will make a preliminary judgment on him.

“Stroke emergency patient.

“43-year-old male, non-smoker, no risk factors.”

Unknown to him, his wife, or even his doctors, he had one major risk factor.

That's a factor that doubles his chances of having a stroke.

It's not uncommon for him to wake up half-paralyzed and to have a number of other conditions that increase his risk.

A common factor that affects approximately two-thirds of the American population is negative childhood experiences (pp. 16-17).

Many people recognize that trauma affects mental health.

Moreover, we usually find the cause of disease in our personal bad lifestyle habits, such as 'smoking a lot', 'drinking a lot of alcohol', 'eating a lot of salty and fatty foods', or 'not exercising'.

However, research conducted over the past two decades in scientific fields such as biology, immunology, clinical medicine, and social epidemiology has yielded very different results.

Severe and repetitive stress experienced during childhood has been shown to have a significant impact on physical health, including autoimmune diseases, obesity, heart disease, and shortened life expectancy.

Nadin Burk Harris, a pediatrician and public health expert, opened her clinic in 2007 in Hunters Point, a poor neighborhood in Bayview, San Francisco.

And there, I met countless young patients who came to my clinic with unusual symptoms.

From children who struggled with severe growth retardation because they couldn't gain weight to those whose asthma flared up every time their father slammed the wall, Harris witnessed firsthand how the trauma inflicted on children by abuse, neglect, parental alcohol and drug addiction, mental illness, and divorce manifested itself in devastating physical ailments.

Meeting children who struggle to recover with conventional treatments, Harris begins to wonder if negative childhood experiences can have profound effects not only on mental health but also on the immune system and brain development, ultimately impacting physical health.

『How Unhappiness Leads to Illness (Original title: The Deepest Well, published by Simsim)』 is a book about the process in which the author, a doctor and public health expert, sought practical evidence based on the latest scientific research to solve questions surrounding physical health and mental suffering that were difficult to understand over the past 10 years, and confirmed in clinical practice ways to reduce the impact of negative childhood experiences.

Drawing on his clinical experience and knowledge, Harris provides insightful answers to questions such as why childhood trauma occurs, why exposure to stress in childhood can lead to health problems in middle age and retirement, what effective treatments are available, and what we can do to protect our health and that of our children.

A doctor's life changed by a child who would never grow up again.

A large-scale epidemiological study of 17,421 people reveals the surprising truth about childhood trauma.

Among the many children Harris met in his clinic, there was one who completely changed his life as a doctor.

Diego, a child of Mexican immigrant descent, came to the clinic with suspicion of ADHD due to several behavioral problems at school.

In addition to his poor impulse control, Diego also suffered from chronic asthma and eczema.

But the biggest problem Harris discovered was Diego's height.

Seven-year-old Diego was not just shorter than his peers, but also very short, about the average height for a four-year-old. (p. 28)

While reviewing Diego's health and upbringing, Harris learned that the boy had been sexually abused by his parents and a close friend as a child, and that since then, his behavior had been suggestive of ADHD and his health had deteriorated significantly.

If only a few children had suffered overwhelming hardship and suffered ill health, it might have been a coincidence, but Diego was a poster child for the hundreds of children Harris had met. (p. 34) The suffering of these children, living in a place where social resources are scarce and poverty and violence are the norm, was palpable.

While Harris was looking into Diego's stunted growth, he came across a paper that raised the possibility that there might be a biological link between childhood adversity and impaired health.

In 1998, the American Journal of Preventative Medicine published a paper titled “Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study” (hereafter, the ACE Study), written by internist Vincent Felitt and epidemiologist Robert Anda.

This study is the first to examine the relationship between high-intensity stress from childhood adversity and poor health, using a survey of 17,421 adults and multiple interviews. (p. 75) The specific findings presented in the paper are as follows:

First, negative childhood experiences are surprisingly common.

Sixty-seven percent of the population had at least one negative experience, and 12.6 percent had four or more.

Second, there is a dose-response relationship between negative childhood experiences and poor health.

In other words, the more negative experiences you have, the greater the risk to your health.

People who had experienced four or more of these conditions were twice as likely to develop heart disease and cancer and 3.5 times as likely to develop chronic obstructive pulmonary disease compared to those who had not experienced them (p. 88).

This paper objectively demonstrated the link between childhood trauma and physical health, something Harris had never heard of during his medical studies.

Harris felt as if all the questions he had been holding onto had been answered at once.

Despite using the best treatment methods, his children's health remained stagnant. He was increasingly seeing the connection between unhappiness and health problems, but he was at a loss as to how to resolve the issue. The ACE research paper opened a new path for him.

And from then on, Harris's life takes a rapid turn toward a larger sea.

He decided to help the young patients who came to him and find practical ways to relieve them of the suffering they would face in the future.

Constant and repetitive stress affects the nervous, immune, and hormonal systems.

The relationship between disease and unhappiness revealed through cutting-edge science, including brain science, neuroscience, immunology, and clinical medicine.

It is widely known through numerous studies and books that trauma is etched in the body and has long-lasting emotional and psychological effects.

The book goes a step further, saying that persistent, repetitive stress, which is difficult for children to handle, affects not only the nervous system but also the immune, hormonal, and cardiovascular systems, causing lifelong health problems.

And this is clearly proven by mobilizing the latest science, including brain science, neuroscience, immunology, and clinical medicine.

When our bodies sense danger, they trigger violent chemical reactions to protect themselves.

And most importantly, your body remembers.

The stress response system is a miraculous product of evolution that has allowed humanity to survive and thrive to this day.

We all have a stress response system that is finely tuned by genetics and early life experiences and is highly individualized. (p. 106)

The problem is that when the stress response is activated too often or the stressor is too intense, our body's stress thermostat breaks down.

When a certain temperature is reached, the supply of 'heat' should be cut off, but what happens is that the body continues to pour cortisol (a hormone that helps the body adapt to repeated or long-term stressors) throughout the body's system. (p. 116) So it is dangerous for a child to be exposed to toxic stress, that is, strong, frequent, and long-lasting negative experiences such as physical and emotional abuse, neglect, substance abuse or mental illness of a caregiver, violence, or severe financial hardship.

In addition, the effects of toxic stress are more severe if a child exposed to it does not receive appropriate adult support at the appropriate time. (p. 118) Diego was also experiencing toxic stress reactions, and his family members had their own problems and were unable to alleviate his stress.

The combination of symptoms Diego experienced was what happens when the stress response system is activated for long periods of time without proper support.

“Children are particularly sensitive to repetitive stress responses.

High-intensity adversity affects not only the structure and function of the brain, but also the developing immune and hormonal systems, and even the way DNA is read and transcribed.

Once the stress response system is wired into a dysregulated pattern, its biological effects spread and cause problems throughout the body's internal organs.

“The body is like a large, delicate Swiss watch; what happens in the immune system is deeply connected to what happens in the cardiovascular system.” (p. 120)

Harris found that the more negative childhood experiences a person has, the more frequently and intensely their stress response system reacts to multiple stressors.

And it explains in detail how our body responds to stress based on the nervous, hormonal, and immune systems.

The direct effects of adverse childhood experiences on our bodies

1.

The nervous system - the front line of efficiently processing information for survival.

Among the brain regions, the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and noradrenergic nucleus in the locus coeruleus are at the forefront of the stress response.

That's why we suffer the most from stress responses that deviate severely from the norm, and for a long period of time, and as a result, the way we work also fundamentally changes.

The authors focus particularly on the ventral tegmental area (VTA) in understanding how negative childhood experiences lead to long-term problems.

This is the pleasure and reward center, which influences behavior and addiction.

“When the body’s stress response system is continually overloaded, the sensitivity of dopamine receptors becomes disrupted.

Even if you want to feel the same level of pleasure as before, you will need more and more stimulation.

When biological changes in the ventral tegmental area cause cravings for dopamine stimulants like high-sugar, high-fat foods, these changes can also lead to increased risky behaviors. The ACE study demonstrated a dose-response relationship between exposure to adverse childhood experiences and the use of many activities and substances that activate the ventral tegmental area. Compared to those with an ACE score of 0, individuals with an ACE score of 4 or higher were 2.5 times more likely to smoke, 5.5 times more likely to be alcohol dependent, and 10 times more likely to use intravenous drugs.

“Therefore, if we want to prevent young people from becoming dependent on harmful dopamine stimulants like tobacco and alcohol, we must understand how experiencing adversity early in life affects dopamine function in the brain.” (p. 143)

2.

The hormonal system - the area most sensitive to stress responses

Almost everything in our body's hormonal system is affected by stress.

Growth hormone, sex hormones such as estrogen and testosterone, thyroid hormones, and insulin, which regulates blood sugar, all generally decrease in amount during times of stress.

Among the major health effects are dysfunction of the ovaries and testes (also known as the gonads), growth arrest, and obesity.

"We have children with ACE scores of 0, even though they live in the same neighborhood, have the same access to health care, and have the same lack of safe play areas and nutritious food. When we understand the hormonal impact of toxic stress on the hormonal systems of children with high ACE scores, we realize that their overweight isn't solely due to a diet of fast food.

It's not just that we live in food deserts (a general term for neighborhoods lacking nutritious food) and are being raised by parents who think Taco Bell is a healthy alternative to McDonald's.

While these things certainly play a part in exacerbating the problem, they don't tell the whole story.

Our study data demonstrate how powerful the mechanisms underlying toxic stress can be.

In other words, the ambassador's abnormality was also an important cause.

If you grow up in a food desert, it's obviously difficult to be healthy.

“But if your cortisol levels are high and you can’t resist cravings for high-sugar, high-fat foods, it will be even harder to choose broccoli over French fries.” (p. 147)

3.

Immune system - an organ that develops in response to the environment

Just as a baby's brain and nervous system are not fully developed at birth, the immune system continues to develop long after birth.

A baby's immune system develops in response to the environment it encounters over the first few years of life.

When stress response regulation becomes dysregulated, immune and inflammatory responses take a serious hit, because stress hormones affect virtually every component of the immune system.

Studies have shown that dysregulating the stress response increases inflammation, hypersensitivity, and even autoimmune diseases like Graves' disease.

While many people believe these conditions are caused by genetic misfortune, the following research shows that environmental and specific factors, such as childhood adversity, are strongly correlated with autoimmune diseases.

“In the years since the ACE study was first published, scientists have been closely examining the link between adverse childhood experiences and autoimmune diseases.

Research findings show that childhood stress is strongly correlated with autoimmune diseases in both children and adults.

Public health scientist Shanta Dube collaborated with Drs. Feliti and Anda to analyze data from more than 15,000 ACE study participants.

They looked at their ACE index and how often they were hospitalized for autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, type 1 diabetes, celiac disease, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

What Dube discovered was shocking: “People with an ACE score of 2 or higher were more than twice as likely to be hospitalized for autoimmune disease compared to those with a score of 0.” (p. 150)

Whether poor or rich, white or black, negative childhood experiences

It makes us sick silently and fatally by itself.

After analyzing numerous ACE studies, Harris became convinced that identifying people exposed to toxic stress beforehand would not only allow for earlier detection of related conditions but also increase the likelihood of more effective treatment.

Moreover, it was thought that by treating damaged stress response systems, it might even be possible to prevent future diseases.

So he sought out people more powerful and influential than himself to inform them about his negative childhood experiences and find ways to address them.

Then, Harris attended a gathering of highly successful women in San Francisco.

The attendees were all white and comprised of San Francisco's upper-class: lawyers, angel investors, consulting professionals, and successful tech entrepreneurs.

He asked attendees to share their thoughts on how to educate people about ACEs and the importance of screening for toxic stress early.

Surprisingly, half of the ten people who attended the meeting shared their past experiences related to negative childhood experiences (p. 300).

Their pasts, which poured out like a flood, were very similar to what Harris had heard from his own patients: parental mental illness, addiction problems, sexual assault, physical or emotional abuse, domestic violence.

Caroline, who has achieved great success in the IT field, carefully shared her story, showing how a family can be torn apart by negative childhood experiences. (p. 302) Caroline suffered from frequent marital fights and panic disorder due to her husband's inability to control his anger and his tendency to treat her as a possession.

And the young son, who had endured his parents' fights by crying, was exposed to psychological trauma and was diagnosed with ADHD.

After struggling for several years, Caroline was able to break free from the tunnel of pain by ending her marriage and receiving psychotherapy with her son, following her son's courageous words that "we must get out of this terrible situation."

Harris knew that statistically, many people around him had experienced adverse childhood experiences, but this was the first time he had had such an open conversation about these experiences outside of a clinic.

“I say this often, half jokingly.

The biggest difference between Bayview and Pacific Heights is that in Bayview, everyone knows who the uncle who molested you is.

This is not because there are no people in the Pacific Heights area, zip code 94115, who could harm a child, or people with drug addictions or mental illnesses.

“It’s just that people there don’t talk about such things.” (p. 323)

This case shatters the stigma that adverse childhood experiences only affect people from poor communities or people of color, including Black people.

In the ACE study by Feliti and Anda, which provided strong scientific inspiration to Harris, 70 percent of those who had adverse childhood experiences were white and had graduated from college.

But many people try to ignore this, further reinforcing prejudice against the poor and people of color.

Harris, in particular, saw firsthand through this encounter how toxic stress, when fed by concealment and shame, can spiral out of control.

There are concerns that solutions that target only specific communities will not make much progress in solving the problem.

Toxic stress is a story about basic human biology, and negative experiences are a universal problem that occurs everywhere, regardless of race or geography.

That's why, he says, to combat toxic stress, we need to let go of the shame of revealing our pain and blaming certain groups.

That means we need to approach it in the same way we approach solving health problems like the flu or pandemics, based on science.

Prevention is as important as treatment.

How to Prevent Toxic Stress from a Public Health Perspective

This book not only warns of the dangers of the negative effects of childhood stress, but also suggests ways to reduce its impact.

Harris offers six proven strategies to address the effects of toxic stress in clinical settings.

These are getting enough sleep, taking care of your mental health, maintaining healthy relationships, regular exercise, a balanced diet, and mindfulness.

The six elements aim to mitigate the adverse effects of toxic stress on the nervous, endocrine, and immune systems, as previously mentioned.

These six elements are areas where parents and those experiencing toxic stress can clearly see significant benefits if they pay attention and pay attention to them.

But Harris says this isn't enough.

Prevention is more important than treatment.

In particular, he says that problems should be discovered and resolved earlier because the development of the nervous, endocrine, and immune systems during childhood is extremely important in a child's life.

Harris strongly argues that the Toxic Stress Test (ACE test) should be added to the basic tests that measure the health and development of young children (e.g., jaundice test, inborn errors of metabolism test, hearing loss test, etc.) (The ACE test questionnaire that Harris actually used in the medical field is included in the appendix of this book, so that anyone can check their ACE status.)

Furthermore, it is emphasized that efforts at the social and national levels are urgently needed to conduct this test at the level of public health as a whole, rather than at the level of individual hospitals, and to jointly find and implement effective treatments.

One of the representative examples in the field of public health is the story of the well.

In late August 1854, a severe cholera outbreak occurred in London.

The outbreaks were all concentrated around communal wells, but the report states that when the pump handles were removed to make the wells unusable, the outbreaks subsided.

Harris mentions this case, saying, “If 100 people all drank from the same well and 98 of them got diarrhea, you could keep prescribing antibiotics, but you might also pause and ask, ‘What the hell is in this well?’” (p. 44).

Harris believed that prescribing medications to children who came to his clinic without even examining them with a stethoscope was no different from indiscriminately prescribing antibiotics to the patients in the well case.

Rather than rushing to prescribe the medicine that was right in front of him, Harris spent over a decade painstakingly researching what was in the wells children were drinking from, and discovered that they were all linked to toxic stress.

This is why the original title of this book, which emphasizes the importance of prevention rather than simple treatment, is 『The Deepest Well』.

Childhood misfortune is a problem that cannot be solved through the efforts of individuals and families alone.

Another point this book emphasizes is that the family, surrounding environment, and social system surrounding an individual affect that person's health.

Children are infinitely vulnerable and society is ignorant of their suffering.

That is the harsh reality that not only American society but also Korean society faces.

Because everyone only sees their own suffering, the negative influences children receive from their parents and surroundings are often easily ignored.

This is why we only pay brief attention to the issue of child abuse, which often appears in the news.

The various cases contained in this book are not just the sad stories of someone in a faraway land, but could be my own story.

Harris's extensive scientific evidence and diverse case studies will help us understand the problems we face and work together to find solutions.

By caring for children exposed to toxic stress in all the spaces where they grow up—home, community, school—and letting adult victims know, "It's not your fault," we can help our society's Diegos recover and continue to lead healthy lives.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: November 25, 2019

- Page count, weight, size: 440 pages | 582g | 140*210*30mm

- ISBN13: 9791156758006

- ISBN10: 1156758009

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)