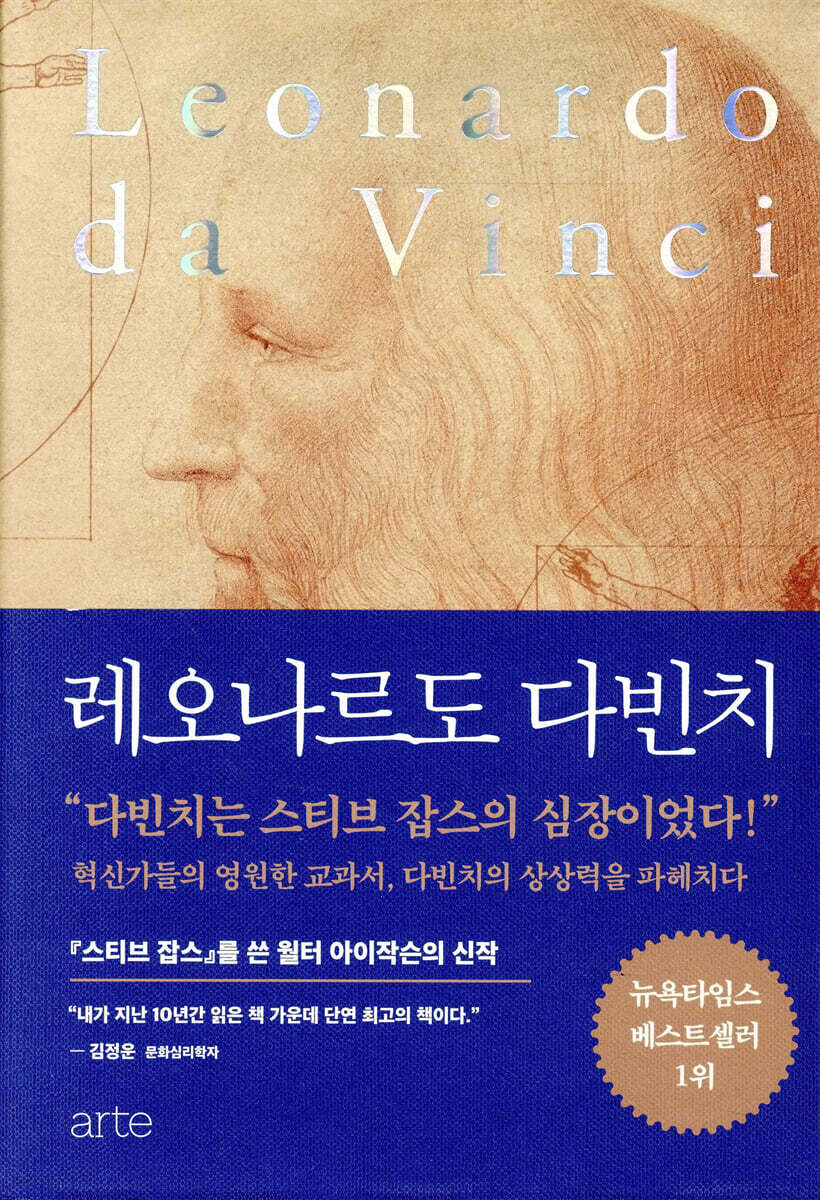

Leonardo da Vinci

|

Description

Book Introduction

“Da Vinci was the heart of Steve Jobs!” Uncovering da Vinci's Imagination: A Timeless Textbook for Innovators Walter Isaacson, who captured the world's attention in 2011 by publishing a biography of Apple founder Steve Jobs, has now published a new biography, "Leonardo da Vinci," which encompasses the life and works of Leonardo da Vinci, after studying the 7,200 pages of notes left by Steve Jobs' hero, Leonardo da Vinci. Walter Isaacson, a journalist and biographer who served as editor-in-chief of Time magazine for over 20 years and CEO of CNN, says that the core of this era is undoubtedly 'creativity', and that it comes from finding intersections between various fields. And it was proven in a book that the person who showed the greatest talent in it was Leonardo da Vinci, who lived in the 15th century. Leonardo da Vinci is a guide to a work beloved across the centuries, and a biography of history's most creative genius, always invoked whenever we discuss creativity. The reason Leonardo da Vinci is often mentioned again and again by the brilliant figures of the 21st century—Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, etc.—is because he, who lived in the 15th century, is still the most innovative figure of the 21st century. |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Acknowledgements

Main characters

Timeline

Preface I can also draw.

1 Childhood

2nd apprentice

3 Standing alone

4 Milado

5 Leonardo's Notebooks

6 Court entertainers

7 Personal Life

8 "Vitruvian Man"

9 Equestrian statues

10 Scientists

11 Birds and Flight

12 Mechanical Engineering

13 Math

14 Human Nature

15 "Our Lady of the Rocks"

16 Milan Portraits

17 The Science of Art

18 "The Last Supper"

19 Personal Adversity

20 Back to Florence

21 St. Anna

22 Lost and Found Paintings

23 Cesare Borgia

24 Mathematical Power

25 Michelangelo and the Lost Battle Paintings

26 Return to Milan

27 Anatomy, Round 2

28 The World and Its Waters

29 Rome

30 Point the way

31 "Mona Lisa"

32 France

33 Conclusion

Describe the tongue of a woodpecker

Abbreviations for frequently cited literature

annotation

Photo source

Search

Main characters

Timeline

Preface I can also draw.

1 Childhood

2nd apprentice

3 Standing alone

4 Milado

5 Leonardo's Notebooks

6 Court entertainers

7 Personal Life

8 "Vitruvian Man"

9 Equestrian statues

10 Scientists

11 Birds and Flight

12 Mechanical Engineering

13 Math

14 Human Nature

15 "Our Lady of the Rocks"

16 Milan Portraits

17 The Science of Art

18 "The Last Supper"

19 Personal Adversity

20 Back to Florence

21 St. Anna

22 Lost and Found Paintings

23 Cesare Borgia

24 Mathematical Power

25 Michelangelo and the Lost Battle Paintings

26 Return to Milan

27 Anatomy, Round 2

28 The World and Its Waters

29 Rome

30 Point the way

31 "Mona Lisa"

32 France

33 Conclusion

Describe the tongue of a woodpecker

Abbreviations for frequently cited literature

annotation

Photo source

Search

Detailed image

.jpg)

Into the book

With a delightful yet obsessive passion, he explored groundbreaking fields such as anatomy, fossils, birds, the heart, flying machines, optics, botany, geology, water flow, and weaponry.

He thus became the quintessential Renaissance man, an inspiration to all who believe in the harmonious interweaving of, as he put it, “the infinite harmonies of nature” to create wondrous patterns.

His ability to combine science and art is epitomized in his "Vitruvian Man," a perfectly proportioned man with outstretched arms and legs within a square and a circle.

These abilities made him one of the most creative geniuses in history. --- pp.17-18

We have a lot to learn from Leonardo.

His ability to combine art, science, technology, and imagination is known today as a formula for exceptional creativity.

The same goes for the ease with which you can comfortably accept things that are a little different from others.

He was illegitimate, homosexual, vegetarian, left-handed, easily distracted, and at times heretical.

Florence was able to prosper in the 15th century because it willingly embraced these people.

And above all, we must mirror Leonardo's persistent curiosity and experimental spirit to remind ourselves and our children of the importance of not just accepting existing knowledge but also questioning it.

We must also learn to think creatively and differently, like the creative misfits and rebels of every era.

--- p.27

Through "The Baptism of Christ," Verrocchio went from being Leonardo's teacher to his partner.

He taught Leonardo the sculptural elements of painting, including the techniques of three-dimensionality, and taught him how the body contorts when moving.

But Leonardo raised art to a whole new level with his translucent and brilliant depictions achieved by applying thin layers of oil paint, and his extraordinary powers of observation and imagination.

From the faint haze on the distant horizon to the shadow under an angel's chin to the water touching Jesus' feet, Leonardo redefined the way a painter transforms and conveys his subjects.

--- p.88

There is another, more fundamental reason why Leonardo did not complete this painting.

He liked the idea itself more than making it a reality.

As his father and others who had signed the strict contract for this work would have known, the twenty-nine-year-old Leonardo was easily distracted by the future rather than focusing on the present.

He was a genius who was not trained in diligence.

--- p.120

He used the classic metaphor of placing the human body, a microcosm, and the Earth, a macrocosm, on the same line.

The city was a breathing organism with circulating fluids and waste products to be excreted.

He had recently begun studying the circulation of blood and fluids in the human body.

Through metaphorical thinking, he pondered what the best circular system for a city would be, from distribution to waste disposal.

(…) Like many of Leonardo's other visionary designs, this concept, which was far ahead of its time, never came to fruition.

Although Ludovico did not adopt Leonardo's vision of the city, in this case Leonardo's proposal is not only ingenious but also reasonable.

Had even a small part of his plan been carried out, it might have completely transformed the city's character, curbed the plague, and altered history.

--- pp.146~147

The more than 7,200 pages of notebooks that survive are estimated to represent about a quarter of Leonardo's entire writings.

But this 500-year-old record is a much higher percentage than the 1990s emails and electronic documents that Steve Jobs and I were able to retrieve.

Leonardo's notebooks are a truly remarkable windfall, providing a detailed record of the application of creativity.

(…) Because good paper was expensive, Leonardo tried to use it to fill the edges of most pages.

Each page is filled with as much content as possible, and content from various seemingly unrelated fields is mixed together in a jumble.

He would go back to pages he had written months or even years ago and refine them as he evolved and matured.

Just as he later recolored "Saint Jerome in the Wilderness" and refined the works he would paint later over a long period of time. --- pp. 150-151

Leonardo became famous in Milan not only for his talent but also for his good looks, muscular physique, and affectionate personality.

Vasari said of Leonardo, “He was a man of striking beauty and infinite grace, a man of exceptional good looks, and his extraordinary presence brought solace to suffering souls.”

(…) Above all, he was famous for sharing what he had with others.

“He was so generous that he fed and housed all his friends, rich and poor,” Vasari reports.

He did not attach importance to wealth or material possessions.

He even wrote in his notes criticizing “people who pursue only material wealth and have no desire for knowledge, which is the most reliable and nourishing asset for human beings.”

So he devoted more time to the pursuit of knowledge than to trying to earn more money than was necessary to support his growing family.

“He owned nothing and did little, but he always had servants and horses,” Vasari reports.

--- pp.178~179

The gaze of the 'Vitruvian Man' is as intense as that of a person looking into a mirror.

Maybe this is actually a scene of looking into a mirror.

Toby Lester, who wrote a book about this painting, says:

“This is an idealized self-portrait of Leonardo.

He stripped himself of everything, leaving only his essence, measured himself, and in doing so embodied the eternal hope of humanity.

It was a hope that we might have the ability to figure out what kind of being we are in the grand scheme of things.

Let us consider this painting as an act of speculation, a metaphysical self-portrait in which Leonardo, as artist, natural philosopher, and representative of all humanity, contemplates himself with a furrowed brow, searching for the secret of his own essence.”

Leonardo's "Vitruvian Man" embodies a moment that combines art and science to contemplate eternal questions such as what it means to be a finite human being and how we fit into the vast cosmic order.

It also symbolizes the humanistic ideal of valuing the dignity, worth, and rationality of each individual human being.

We can see the essence of Leonardo da Vinci, standing naked at the intersection of the earthly and the cosmic, in the square and the circle, and our own essence.

--- pp.213~214

When Leonardo painted the Vitruvian Man, his mind was overflowing with various, closely related ideas.

It was the construction of a square with the same area as a circle, the similarity between the microcosm of humanity and the macrocosm of the Earth, the geometry of squares and circles in church architecture, the variation of geometric forms, and the concept of combining mathematics and art called the 'golden section' or 'divine proportion'.

As he pondered these topics, he did not rely solely on his own experiences and reading, but rather developed his thoughts through conversations with friends and colleagues.

Like many thinkers who dabbled in multiple disciplines, for Leonardo the advancement of thought was possible through collaboration.

Unlike artists like Michelangelo, who were always in agony, Leonardo enjoyed being surrounded by friends, colleagues, students, assistants, courtiers, and thinkers.

His notes reveal the names of dozens of people he wanted to share his thoughts with.

His closest friends were intellectuals.

This process of sharing thoughts and creating new ideas together was further facilitated by visiting Renaissance courts such as the Milanese court.

Among those receiving salaries from the Sforza court were not only musicians and performers, but also architects, medical researchers, and scientists from various fields.

They helped Leonardo continue to learn new things and satisfy his endless curiosity.

Bernardo Bellincioni, the court poet, who was more famous for his flattery than his brilliant poetry, described the various talents Ludovico cared for:

“Ludovico’s court is full of artists.

“All learned scholars flock to him like bees to the scent of honey.” He compared Leonardo to the greatest ancient Greek painter.

“He came here from Florence, leading Apelles.” --- pp.214~215

Leonardo did not remain merely a disciple of experience.

His evolution can be seen in his notes.

He began absorbing knowledge from books in the 1490s, which led him to realize the importance of being guided by theoretical systems as well as empirical evidence.

More importantly, I came to understand that these two have a close and complementary relationship.

“In Leonardo we find a dramatic attempt to properly assess the interrelationship between theory and experiment,” wrote the 20th-century physicist Leopold Infeld.

--- pp.233~234

In addition to his instinct for recognizing patterns in various fields, Leonardo developed two abilities that were useful in scientific research.

It was a curiosity so varied as to be almost fanatical, and a frighteningly sharp and sharp observation.

As with most other parts of Leonardo, these two are interconnected.

Anyone who can put “Describe a woodpecker’s tongue” on their to-do list is probably born with an inordinate amount of curiosity and perceptiveness.

Like Einstein, Leonardo's curiosity led him to notice phenomena that most people stop wondering about after the age of ten.

Why is the sky blue? How do clouds form? Why do our eyes only see in straight lines? What is a yawn? Einstein attributed his fascination with the mundane to learning to speak late in life.

In Leonardo's case, this talent may have been due to growing up as a child who loved nature while not being overly indoctrinated with existing knowledge.

Other topics he wrote down in his notebooks out of curiosity were more ambitious and required investigative observation.

“What nerve moves the eyes, so that the movement of one eye causes the movement of the other?” “Describe the beginning of man in the womb.” In addition to the woodpecker, he also wanted to look at things like “the jaw of a crocodile” and “the placenta of a cow.”

These things were only possible with tremendous effort.

His curiosity was aided by his keen eye.

He noticed things most of us miss.

One night I saw lightning flash behind the buildings, and at that moment the buildings seemed smaller than usual.

Through a series of experiments and controlled observations, he discovered that objects appear smaller in bright light and larger when shrouded in fog or darkness.

After discovering that objects appear less three-dimensional when one eye is closed than when both eyes are open, I tried to figure out why.

--- pp.238~239

By studying machines, Leonardo came to see the world from a mechanistic perspective, ahead of Newton.

He concluded that all motion in the universe, including 'human limbs, cogs in machines, human blood, and river water,' follows the same laws.

There are similarities between these laws.

Movements in one area can be compared to movements in other areas, and patterns can be revealed.

“Man is a machine, birds are machines, the whole universe is a machine,” said Marco Cianchi, who analyzed Leonardo’s devices.

While Leonardo and others led Europe into a new scientific age, he also ridiculed those who believed in non-mechanical interpretations of cause and effect, such as astrologers and alchemists, and relegated religious miracles to the realm of the priests.

--- p.263

Leonardo was one of the most well-trained observers of nature in history, but his observation worked closely with his imagination rather than clashing with it.

Like his love of art and science, his observation and imagination were closely linked and became the warp and woof of his genius.

He was a man of integrated creativity.

Just as he could create a dragon-like monster by adding various animal parts to a real lizard, he could take the details and patterns of nature and then mix them with the products of his imagination, whether for social tricks or for imagining.

Not surprisingly, Leonardo sought scientific evidence for this ability.

While studying anatomy and mapping the human brain, he observed that the capacity for imagination, which could interact closely with the capacity for rational thought, existed within the ventricles.

--- p.341

The "Madonna and Failure" paintings are tabloid-sized, but they, especially the Lansdowne version, reflect Leonardo's signature genius.

Both mother and son's hair is shiny and tightly curled.

The river flowing down from the mysterious and misty mountains is like an artery connecting the universe called Earth to the blood vessels in the two human bodies.

Leonardo also knew how to express the sunlight reflecting off the Virgin's thin veil, making the veil thinner than her skin but allowing the sunlight to hit the top of her forehead and reflect.

The sunlight illuminates the leaves of the nearest trees, painted next to the Virgin's lap, clearly, but as Leonardo explains in his text on sharp perspective, the trees appear less sharp the further away they are.

Additionally, the rock layers on which Jesus leans reflect Leonardo's scientific precision.

--- pp.399~400

Leonardo's maps are another example of his great but underrated innovation.

He invented new ways to convey information visually.

Leonardo illustrated Pacioli's books on geometry, creating various polyhedral models that appeared three-dimensional due to their perfect lighting and shading.

In his notes on engineering and mechanics, he drew drawings of mechanical devices of exquisite precision and accuracy, even adding scenes showing the various parts taken apart.

He was one of the first to disassemble complex mechanical devices and draw each part separately.

Likewise in anatomical drawings, he pioneered the method of depicting muscles, nerves, bones, organs, and blood vessels from various angles and depicting them in multiple layers.

This is similar to the perspective drawings showing the various layers of the human body that appeared in encyclopedias centuries later.

--- pp.441~442

As a final testament to the breadth of his passions and curiosity, a glance at the back of the pages where the horses are sketched reveals what else he was thinking about at the time.

There's a vibrant horse's head there too, but just above it is a detailed diagram of the solar system, showing the Earth, the Sun, and the Moon, with projection lines that explain why we see the different phases of the Moon.

He analyzed the optical illusion that the moon appears larger when it is hanging over the horizon than when it is in the air.

He wrote that objects appear larger when viewed through a concave lens, and that “this way we could accurately mimic the atmosphere.”

At the very bottom of the page are drawn geometric shapes such as squares and truncated circles.

Leonardo struggled endlessly with the problem of converting geometric figures into other shapes with the same area and constructing a square with the same area as a circle.

Even the horse depicted there has an expression of awe and respect, as if it were astonishing that Leonardo had scattered such evidence of his great spirit around him.

--- p.466

Of all the portraits attributed to Leonardo, the most famous and striking is the impressive drawing he himself drew with red chalk, hatching with his left hand.

Known as the 'Turin Portrait' because it is kept in Turin, Italy, this work has been reproduced so many times that it has come to define our image of Leonardo, whether or not it is an actual self-portrait.

It depicts an old man with a long beard, curly hair, and bushy eyebrows.

The sharp lines of the hair contrast with the cheeks, which are depicted in a soft sfumato technique.

The nose, expressed three-dimensionally through soft shadows and hatching of straight and curved lines, is slightly crooked, but not as severely hooked as in Leonardo's old man's drawings.

As in many of Leonardo's works, this face is a complex mix of emotions that feels different each time you see it: strength and vulnerability, resignation and impatience, fatalism and stern resolve.

The tired eyes seem lost in thought, and the downturned corners of the mouth are gloomy.

--- p.573

It seems logical to view the Mona Lisa as the last work painted, and to explore it as the culmination of a life devoted to developing the ability to stand at the intersection of art and nature.

Completed over many years with multiple layers of glaze on a poplar panel, this work symbolically showcases the many facets of Leonardo's genius.

What began as a portrait of a silk merchant's young wife became a journey to depict the complexities of human emotion conveyed through the mystery of a faint smile, and to explore the connection between our nature and the nature of the universe.

--- pp.601~602

There's another little quirk to the way light hits Lisa's face.

In his writings on optics, Leonardo studied the time it takes for the pupil to constrict when exposed to bright light.

In the case of "Portrait of a Musician," the differently sized pupils of the two eyes gave the painting a sense of movement, and also matched well with the bright light Leonardo used in the painting.

In the case of the Mona Lisa, Lisa's right pupil is slightly larger.

However, the right eye is more directly facing the light coming from the right (it was facing the light source even before turning the head), so the right pupil should be smaller.

Just as the refraction of the crystal sphere in "Salvator Mundi" was not properly depicted, was this a simple mistake or a clever trick? Was Leonardo observant enough to notice the unequal pupil size that occurs in 20 percent of the population? Or did he know that pleasure also causes pupil dilation, and by dilating one of Lisa's pupils more quickly than the other, he was expressing Lisa's pleasure at seeing us?

Maybe this is just over-obsessing over something so trivial and unimportant.

Let's call this the 'Leonardo Effect'.

His powers of observation are so keen that even vague anomalies, such as pupils of different sizes, make us ponder, perhaps to an exaggerated degree, what he might have discovered and what he might have thought.

If so, this is a good thing.

By being around him, we become more attentive to the details of nature, such as the cause of pupil dilation, and are struck with a renewed sense of wonder.

Driven by his desire to notice every detail, we strive to do the same.

--- pp.611~612

Through his studies of optics, Leonardo realized that light does not focus on one point in the eye, but enters the entire retina.

The central part of the retina, known as the fovea, is good at recognizing color and fine details, while the peripheral part of the fovea is good at recognizing shadows and shades of black and white.

When we look straight at an object, it appears clear.

However, if you squint using your peripheral vision, objects appear slightly blurry, as if they are far away.

Using this knowledge, Leonardo was able to create a smile that was elusive, a smile that was invisible if you tried too hard to look at it.

The very thin line drawn at the corner of Lisa's mouth is slightly downward, like the lips drawn at the top of the anatomy page.

If we look straight at that mouth, our retinas will recognize these fine details and lines, so it looks like Lisa is not smiling.

But if we look away from the mouth and look at the eyes, cheeks, or other parts of the picture, we only see Lisa's mouth in our peripheral vision.

The small lines at the corners of the mouth are blurred, but the shadows there are still visible.

This lip shadow and soft sfumato technique makes the corners of Lisa's mouth appear slightly upturned, forming a subtle smile.

As a result, the less you try to look at it, the brighter your smile will shine.

--- pp.618~619

As is always the case with Leonardo, a veil of mystery surrounds everything: his art and his life, from his birthplace to his death.

We cannot, and do not wish to, describe him in a precise line.

Leonardo probably wouldn't have wanted to paint the Mona Lisa that way either.

It's not a bad idea to leave it to our imagination a little bit.

As he knew, the outlines of reality are inevitably blurred, leaving some uncertainty that we must accept.

The best way to approach his life is the same way he approached the world.

With eyes full of curiosity, marveling at the infinite wonders of this world. --- p.652

There were, of course, many polymaths with a strong thirst for knowledge, and the Renaissance period produced many Renaissance people.

But none of them painted the Mona Lisa.

At the same time, no one could have drawn unparalleled anatomical diagrams through multiple dissections, devised plans for waterway diversions, explained the reflection of light from the Earth to the Moon, opened the beating heart of a slaughtered pig to determine the workings of its ventricles, designed a musical instrument, planned a pageant, used fossils to refute the Biblical flood story, and then painted a picture of the flood itself.

Leonardo was a genius, but he was more than that.

He was the epitome of a universal intellectual who sought to understand all creation and our place in it.

--- pp.655~656

At some point in life, most of us stop thinking deeply about everyday phenomena.

You may briefly admire the beauty of the blue sky, but you no longer wonder why the sky is that color.

Leonardo wondered.

Einstein was no exception, writing to another friend:

“You and I must never cease to stand like curious children before the wonderful mysteries of this world into which we were born.” We must be careful not to lose that childlike wonder about everything, and we must not let our children do the same.

He thus became the quintessential Renaissance man, an inspiration to all who believe in the harmonious interweaving of, as he put it, “the infinite harmonies of nature” to create wondrous patterns.

His ability to combine science and art is epitomized in his "Vitruvian Man," a perfectly proportioned man with outstretched arms and legs within a square and a circle.

These abilities made him one of the most creative geniuses in history. --- pp.17-18

We have a lot to learn from Leonardo.

His ability to combine art, science, technology, and imagination is known today as a formula for exceptional creativity.

The same goes for the ease with which you can comfortably accept things that are a little different from others.

He was illegitimate, homosexual, vegetarian, left-handed, easily distracted, and at times heretical.

Florence was able to prosper in the 15th century because it willingly embraced these people.

And above all, we must mirror Leonardo's persistent curiosity and experimental spirit to remind ourselves and our children of the importance of not just accepting existing knowledge but also questioning it.

We must also learn to think creatively and differently, like the creative misfits and rebels of every era.

--- p.27

Through "The Baptism of Christ," Verrocchio went from being Leonardo's teacher to his partner.

He taught Leonardo the sculptural elements of painting, including the techniques of three-dimensionality, and taught him how the body contorts when moving.

But Leonardo raised art to a whole new level with his translucent and brilliant depictions achieved by applying thin layers of oil paint, and his extraordinary powers of observation and imagination.

From the faint haze on the distant horizon to the shadow under an angel's chin to the water touching Jesus' feet, Leonardo redefined the way a painter transforms and conveys his subjects.

--- p.88

There is another, more fundamental reason why Leonardo did not complete this painting.

He liked the idea itself more than making it a reality.

As his father and others who had signed the strict contract for this work would have known, the twenty-nine-year-old Leonardo was easily distracted by the future rather than focusing on the present.

He was a genius who was not trained in diligence.

--- p.120

He used the classic metaphor of placing the human body, a microcosm, and the Earth, a macrocosm, on the same line.

The city was a breathing organism with circulating fluids and waste products to be excreted.

He had recently begun studying the circulation of blood and fluids in the human body.

Through metaphorical thinking, he pondered what the best circular system for a city would be, from distribution to waste disposal.

(…) Like many of Leonardo's other visionary designs, this concept, which was far ahead of its time, never came to fruition.

Although Ludovico did not adopt Leonardo's vision of the city, in this case Leonardo's proposal is not only ingenious but also reasonable.

Had even a small part of his plan been carried out, it might have completely transformed the city's character, curbed the plague, and altered history.

--- pp.146~147

The more than 7,200 pages of notebooks that survive are estimated to represent about a quarter of Leonardo's entire writings.

But this 500-year-old record is a much higher percentage than the 1990s emails and electronic documents that Steve Jobs and I were able to retrieve.

Leonardo's notebooks are a truly remarkable windfall, providing a detailed record of the application of creativity.

(…) Because good paper was expensive, Leonardo tried to use it to fill the edges of most pages.

Each page is filled with as much content as possible, and content from various seemingly unrelated fields is mixed together in a jumble.

He would go back to pages he had written months or even years ago and refine them as he evolved and matured.

Just as he later recolored "Saint Jerome in the Wilderness" and refined the works he would paint later over a long period of time. --- pp. 150-151

Leonardo became famous in Milan not only for his talent but also for his good looks, muscular physique, and affectionate personality.

Vasari said of Leonardo, “He was a man of striking beauty and infinite grace, a man of exceptional good looks, and his extraordinary presence brought solace to suffering souls.”

(…) Above all, he was famous for sharing what he had with others.

“He was so generous that he fed and housed all his friends, rich and poor,” Vasari reports.

He did not attach importance to wealth or material possessions.

He even wrote in his notes criticizing “people who pursue only material wealth and have no desire for knowledge, which is the most reliable and nourishing asset for human beings.”

So he devoted more time to the pursuit of knowledge than to trying to earn more money than was necessary to support his growing family.

“He owned nothing and did little, but he always had servants and horses,” Vasari reports.

--- pp.178~179

The gaze of the 'Vitruvian Man' is as intense as that of a person looking into a mirror.

Maybe this is actually a scene of looking into a mirror.

Toby Lester, who wrote a book about this painting, says:

“This is an idealized self-portrait of Leonardo.

He stripped himself of everything, leaving only his essence, measured himself, and in doing so embodied the eternal hope of humanity.

It was a hope that we might have the ability to figure out what kind of being we are in the grand scheme of things.

Let us consider this painting as an act of speculation, a metaphysical self-portrait in which Leonardo, as artist, natural philosopher, and representative of all humanity, contemplates himself with a furrowed brow, searching for the secret of his own essence.”

Leonardo's "Vitruvian Man" embodies a moment that combines art and science to contemplate eternal questions such as what it means to be a finite human being and how we fit into the vast cosmic order.

It also symbolizes the humanistic ideal of valuing the dignity, worth, and rationality of each individual human being.

We can see the essence of Leonardo da Vinci, standing naked at the intersection of the earthly and the cosmic, in the square and the circle, and our own essence.

--- pp.213~214

When Leonardo painted the Vitruvian Man, his mind was overflowing with various, closely related ideas.

It was the construction of a square with the same area as a circle, the similarity between the microcosm of humanity and the macrocosm of the Earth, the geometry of squares and circles in church architecture, the variation of geometric forms, and the concept of combining mathematics and art called the 'golden section' or 'divine proportion'.

As he pondered these topics, he did not rely solely on his own experiences and reading, but rather developed his thoughts through conversations with friends and colleagues.

Like many thinkers who dabbled in multiple disciplines, for Leonardo the advancement of thought was possible through collaboration.

Unlike artists like Michelangelo, who were always in agony, Leonardo enjoyed being surrounded by friends, colleagues, students, assistants, courtiers, and thinkers.

His notes reveal the names of dozens of people he wanted to share his thoughts with.

His closest friends were intellectuals.

This process of sharing thoughts and creating new ideas together was further facilitated by visiting Renaissance courts such as the Milanese court.

Among those receiving salaries from the Sforza court were not only musicians and performers, but also architects, medical researchers, and scientists from various fields.

They helped Leonardo continue to learn new things and satisfy his endless curiosity.

Bernardo Bellincioni, the court poet, who was more famous for his flattery than his brilliant poetry, described the various talents Ludovico cared for:

“Ludovico’s court is full of artists.

“All learned scholars flock to him like bees to the scent of honey.” He compared Leonardo to the greatest ancient Greek painter.

“He came here from Florence, leading Apelles.” --- pp.214~215

Leonardo did not remain merely a disciple of experience.

His evolution can be seen in his notes.

He began absorbing knowledge from books in the 1490s, which led him to realize the importance of being guided by theoretical systems as well as empirical evidence.

More importantly, I came to understand that these two have a close and complementary relationship.

“In Leonardo we find a dramatic attempt to properly assess the interrelationship between theory and experiment,” wrote the 20th-century physicist Leopold Infeld.

--- pp.233~234

In addition to his instinct for recognizing patterns in various fields, Leonardo developed two abilities that were useful in scientific research.

It was a curiosity so varied as to be almost fanatical, and a frighteningly sharp and sharp observation.

As with most other parts of Leonardo, these two are interconnected.

Anyone who can put “Describe a woodpecker’s tongue” on their to-do list is probably born with an inordinate amount of curiosity and perceptiveness.

Like Einstein, Leonardo's curiosity led him to notice phenomena that most people stop wondering about after the age of ten.

Why is the sky blue? How do clouds form? Why do our eyes only see in straight lines? What is a yawn? Einstein attributed his fascination with the mundane to learning to speak late in life.

In Leonardo's case, this talent may have been due to growing up as a child who loved nature while not being overly indoctrinated with existing knowledge.

Other topics he wrote down in his notebooks out of curiosity were more ambitious and required investigative observation.

“What nerve moves the eyes, so that the movement of one eye causes the movement of the other?” “Describe the beginning of man in the womb.” In addition to the woodpecker, he also wanted to look at things like “the jaw of a crocodile” and “the placenta of a cow.”

These things were only possible with tremendous effort.

His curiosity was aided by his keen eye.

He noticed things most of us miss.

One night I saw lightning flash behind the buildings, and at that moment the buildings seemed smaller than usual.

Through a series of experiments and controlled observations, he discovered that objects appear smaller in bright light and larger when shrouded in fog or darkness.

After discovering that objects appear less three-dimensional when one eye is closed than when both eyes are open, I tried to figure out why.

--- pp.238~239

By studying machines, Leonardo came to see the world from a mechanistic perspective, ahead of Newton.

He concluded that all motion in the universe, including 'human limbs, cogs in machines, human blood, and river water,' follows the same laws.

There are similarities between these laws.

Movements in one area can be compared to movements in other areas, and patterns can be revealed.

“Man is a machine, birds are machines, the whole universe is a machine,” said Marco Cianchi, who analyzed Leonardo’s devices.

While Leonardo and others led Europe into a new scientific age, he also ridiculed those who believed in non-mechanical interpretations of cause and effect, such as astrologers and alchemists, and relegated religious miracles to the realm of the priests.

--- p.263

Leonardo was one of the most well-trained observers of nature in history, but his observation worked closely with his imagination rather than clashing with it.

Like his love of art and science, his observation and imagination were closely linked and became the warp and woof of his genius.

He was a man of integrated creativity.

Just as he could create a dragon-like monster by adding various animal parts to a real lizard, he could take the details and patterns of nature and then mix them with the products of his imagination, whether for social tricks or for imagining.

Not surprisingly, Leonardo sought scientific evidence for this ability.

While studying anatomy and mapping the human brain, he observed that the capacity for imagination, which could interact closely with the capacity for rational thought, existed within the ventricles.

--- p.341

The "Madonna and Failure" paintings are tabloid-sized, but they, especially the Lansdowne version, reflect Leonardo's signature genius.

Both mother and son's hair is shiny and tightly curled.

The river flowing down from the mysterious and misty mountains is like an artery connecting the universe called Earth to the blood vessels in the two human bodies.

Leonardo also knew how to express the sunlight reflecting off the Virgin's thin veil, making the veil thinner than her skin but allowing the sunlight to hit the top of her forehead and reflect.

The sunlight illuminates the leaves of the nearest trees, painted next to the Virgin's lap, clearly, but as Leonardo explains in his text on sharp perspective, the trees appear less sharp the further away they are.

Additionally, the rock layers on which Jesus leans reflect Leonardo's scientific precision.

--- pp.399~400

Leonardo's maps are another example of his great but underrated innovation.

He invented new ways to convey information visually.

Leonardo illustrated Pacioli's books on geometry, creating various polyhedral models that appeared three-dimensional due to their perfect lighting and shading.

In his notes on engineering and mechanics, he drew drawings of mechanical devices of exquisite precision and accuracy, even adding scenes showing the various parts taken apart.

He was one of the first to disassemble complex mechanical devices and draw each part separately.

Likewise in anatomical drawings, he pioneered the method of depicting muscles, nerves, bones, organs, and blood vessels from various angles and depicting them in multiple layers.

This is similar to the perspective drawings showing the various layers of the human body that appeared in encyclopedias centuries later.

--- pp.441~442

As a final testament to the breadth of his passions and curiosity, a glance at the back of the pages where the horses are sketched reveals what else he was thinking about at the time.

There's a vibrant horse's head there too, but just above it is a detailed diagram of the solar system, showing the Earth, the Sun, and the Moon, with projection lines that explain why we see the different phases of the Moon.

He analyzed the optical illusion that the moon appears larger when it is hanging over the horizon than when it is in the air.

He wrote that objects appear larger when viewed through a concave lens, and that “this way we could accurately mimic the atmosphere.”

At the very bottom of the page are drawn geometric shapes such as squares and truncated circles.

Leonardo struggled endlessly with the problem of converting geometric figures into other shapes with the same area and constructing a square with the same area as a circle.

Even the horse depicted there has an expression of awe and respect, as if it were astonishing that Leonardo had scattered such evidence of his great spirit around him.

--- p.466

Of all the portraits attributed to Leonardo, the most famous and striking is the impressive drawing he himself drew with red chalk, hatching with his left hand.

Known as the 'Turin Portrait' because it is kept in Turin, Italy, this work has been reproduced so many times that it has come to define our image of Leonardo, whether or not it is an actual self-portrait.

It depicts an old man with a long beard, curly hair, and bushy eyebrows.

The sharp lines of the hair contrast with the cheeks, which are depicted in a soft sfumato technique.

The nose, expressed three-dimensionally through soft shadows and hatching of straight and curved lines, is slightly crooked, but not as severely hooked as in Leonardo's old man's drawings.

As in many of Leonardo's works, this face is a complex mix of emotions that feels different each time you see it: strength and vulnerability, resignation and impatience, fatalism and stern resolve.

The tired eyes seem lost in thought, and the downturned corners of the mouth are gloomy.

--- p.573

It seems logical to view the Mona Lisa as the last work painted, and to explore it as the culmination of a life devoted to developing the ability to stand at the intersection of art and nature.

Completed over many years with multiple layers of glaze on a poplar panel, this work symbolically showcases the many facets of Leonardo's genius.

What began as a portrait of a silk merchant's young wife became a journey to depict the complexities of human emotion conveyed through the mystery of a faint smile, and to explore the connection between our nature and the nature of the universe.

--- pp.601~602

There's another little quirk to the way light hits Lisa's face.

In his writings on optics, Leonardo studied the time it takes for the pupil to constrict when exposed to bright light.

In the case of "Portrait of a Musician," the differently sized pupils of the two eyes gave the painting a sense of movement, and also matched well with the bright light Leonardo used in the painting.

In the case of the Mona Lisa, Lisa's right pupil is slightly larger.

However, the right eye is more directly facing the light coming from the right (it was facing the light source even before turning the head), so the right pupil should be smaller.

Just as the refraction of the crystal sphere in "Salvator Mundi" was not properly depicted, was this a simple mistake or a clever trick? Was Leonardo observant enough to notice the unequal pupil size that occurs in 20 percent of the population? Or did he know that pleasure also causes pupil dilation, and by dilating one of Lisa's pupils more quickly than the other, he was expressing Lisa's pleasure at seeing us?

Maybe this is just over-obsessing over something so trivial and unimportant.

Let's call this the 'Leonardo Effect'.

His powers of observation are so keen that even vague anomalies, such as pupils of different sizes, make us ponder, perhaps to an exaggerated degree, what he might have discovered and what he might have thought.

If so, this is a good thing.

By being around him, we become more attentive to the details of nature, such as the cause of pupil dilation, and are struck with a renewed sense of wonder.

Driven by his desire to notice every detail, we strive to do the same.

--- pp.611~612

Through his studies of optics, Leonardo realized that light does not focus on one point in the eye, but enters the entire retina.

The central part of the retina, known as the fovea, is good at recognizing color and fine details, while the peripheral part of the fovea is good at recognizing shadows and shades of black and white.

When we look straight at an object, it appears clear.

However, if you squint using your peripheral vision, objects appear slightly blurry, as if they are far away.

Using this knowledge, Leonardo was able to create a smile that was elusive, a smile that was invisible if you tried too hard to look at it.

The very thin line drawn at the corner of Lisa's mouth is slightly downward, like the lips drawn at the top of the anatomy page.

If we look straight at that mouth, our retinas will recognize these fine details and lines, so it looks like Lisa is not smiling.

But if we look away from the mouth and look at the eyes, cheeks, or other parts of the picture, we only see Lisa's mouth in our peripheral vision.

The small lines at the corners of the mouth are blurred, but the shadows there are still visible.

This lip shadow and soft sfumato technique makes the corners of Lisa's mouth appear slightly upturned, forming a subtle smile.

As a result, the less you try to look at it, the brighter your smile will shine.

--- pp.618~619

As is always the case with Leonardo, a veil of mystery surrounds everything: his art and his life, from his birthplace to his death.

We cannot, and do not wish to, describe him in a precise line.

Leonardo probably wouldn't have wanted to paint the Mona Lisa that way either.

It's not a bad idea to leave it to our imagination a little bit.

As he knew, the outlines of reality are inevitably blurred, leaving some uncertainty that we must accept.

The best way to approach his life is the same way he approached the world.

With eyes full of curiosity, marveling at the infinite wonders of this world. --- p.652

There were, of course, many polymaths with a strong thirst for knowledge, and the Renaissance period produced many Renaissance people.

But none of them painted the Mona Lisa.

At the same time, no one could have drawn unparalleled anatomical diagrams through multiple dissections, devised plans for waterway diversions, explained the reflection of light from the Earth to the Moon, opened the beating heart of a slaughtered pig to determine the workings of its ventricles, designed a musical instrument, planned a pageant, used fossils to refute the Biblical flood story, and then painted a picture of the flood itself.

Leonardo was a genius, but he was more than that.

He was the epitome of a universal intellectual who sought to understand all creation and our place in it.

--- pp.655~656

At some point in life, most of us stop thinking deeply about everyday phenomena.

You may briefly admire the beauty of the blue sky, but you no longer wonder why the sky is that color.

Leonardo wondered.

Einstein was no exception, writing to another friend:

“You and I must never cease to stand like curious children before the wonderful mysteries of this world into which we were born.” We must be careful not to lose that childlike wonder about everything, and we must not let our children do the same.

--- p.657

Publisher's Review

“He is still the most innovative person of the 21st century!”

Steve Jobs, Bill Gates… Role models of the luminaries of the 21st century.

“The Secret to Creativity in Da Vinci’s 7,200-Page Notebook!”

A new book by Walter Isaacson, author of "Steve Jobs"!

Steve Jobs, who considered Leonardo da Vinci his hero,

Bill Gates bought a Da Vinci notebook for 34.9 billion won.

2019 marks the 500th anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci's death.

Born in Florence in 1452 and dying at the age of 67 in 1519, 500 years have passed since then, but Leonardo da Vinci's works and life still exert a powerful influence on people living in the 21st century.

Steve Jobs said that Leonardo “found beauty in both art and engineering, and his ability to bring the two together was what made him a genius.”

As is well known, Jobs rose to the top of the IT industry by combining new technologies with trendy designs.

Technology cannot advance without imagination.

Technology that lacks imagination attracts no one's attention.

Meanwhile, Bill Gates, who founded Microsoft, spent $30.8 million (approximately 34.9 billion won) on a 72-page set of Leonardo's notebooks (the 'Codex Leicester'), and commented, "Leonardo is the most fascinating person in history."

Leonardo da Vinci, the all-too-human genius

What is the secret to that creativity?

Walter Isaacson has presented a fascinating backstory of each of Leonardo da Vinci's works, and he also provides a wealth of information about the process of identifying Leonardo's authentic works.

However, among the numerous biographies of Leonardo da Vinci, Walter Isaacson's stands out because it presents 'Leonardo da Vinci the man.'

Bill Gates, who is so interested in Leonardo da Vinci that he owns his notebooks, known as the 'Codex Leicester,' said, "I've read quite a few books about Leonardo over the years.

“But I have never found a book that explores the other aspects of his life and work so well as to my satisfaction,” he said, recommending Isaacson’s biography, saying it “will show readers how human Leonardo was, and at the same time, how extraordinary he was.”

The New York Times also noted that while a common pitfall of biographies is defining their subjects as overly singular human beings, Isaacson "shines brightest when he talks about what makes Leonardo so human."

Leonardo is a genius.

However, rather than being a natural genius, he is a person who became a genius by solving his endless curiosity with imagination and effort.

Curiosity and imagination are inherent in all human beings.

However, it is like a muscle that deteriorates very easily if not used, so most people lose its function at a very young age.

Leonardo da Vinci was full of curiosity until the last moment of his life, and this is clearly evident in the voluminous notebooks he kept.

That's why Walter Isaacson focused on his notes.

He was a genius.

He was a man of unbridled imagination, burning curiosity, and creativity that encompassed a wide range of fields.

But we must use this expression carefully.

Labeling Leonardo a "genius" actually diminishes his value by making him into a special person who was struck by lightning.

(…) Leonardo's genius was human in nature and was accomplished through personal will and ambition.

He was not born with a superhuman brain like Newton or Einstein that ordinary humans cannot even fathom.

Leonardo had little formal education and could not read Latin or perform complex division.

His genius is of a kind we can fully understand, and even learn from.

It is based on abilities that we can improve ourselves, such as curiosity or keen observation.

Leonardo's unbridled imagination blurred the line between fantasy and fantasy, and this is something we can strive to protect ourselves and nurture in our children.

―From the preface

Leonardo da Vinci has impressed people around the world for centuries with his two famous works, “The Last Supper” and “Mona Lisa.”

But his work is not the product of what we usually call genius, an ability that comes without effort.

Masterpieces are created through constant curiosity, tireless observation and research, and boundless imagination.

As is well known, Leonardo left behind many unfinished works, but this cannot be attributed solely to his laziness.

He had no preconceptions, and because truth was always something new to be discovered, his work could only remain in the process of moving towards completion.

He constantly thought about the relationship between nature and humans, made rational judgments through scientific thinking, and boldly overturned religious thinking.

“Technology without imagination is barren.”

And there is no human being who does not imagine

It is no exaggeration to say that Leonardo lived several centuries ahead of his time.

He discovered, researched, and recorded the beginnings of innovation in various fields such as medicine, dentistry, anatomy, biology, geology, and physics.

He pioneered the scientific revolution a century before Galileo and pioneered the format of human anatomy diagrams used today.

He may be remembered as a pioneer in dentistry, as he was the first person in history to record in detail all the elements of a human tooth, and his notes also contain what may be the first case of arteriosclerosis described.

Leonardo also realized that the heart, not the liver, was the center of the blood system and figured out how the heart functions, but anatomists would not realize he was right until 450 years later.

One day, after seeing fossils of marine life in high altitude areas, he realized that the mountain ranges were formed by uplift of the earth's crust, and biogeography began in earnest 300 years later.

He also argued, contrary to common sense at the time, that embryos were still part of the mother's body, like the mother's hands and feet, and he also noticed that the moon did not emit light of its own but reflected sunlight.

Because his achievements were never officially announced or published, they had to wait anywhere from 100 years to 400 years for later innovators to rediscover them.

He delved into these many fields solely to satisfy his own curiosity.

Thanks to his study of perspective, he was able to dissect the human body and draw each body part in three dimensions on a two-dimensional plane. Through dissection, he realized that his earlier drawings of the muscles in the figures were incorrect and corrected them.

He meticulously dissected and observed the facial and lip muscles to identify the muscles that produce a smile, which likely contributed to creating the beautiful and mysterious smile of the Mona Lisa.

A masterpiece is completed at the tip of a genius's brush, but its seeds were already there in the artist's daily life, which he looked upon with wonder.

It was this attitude of looking at everything in the world with wonder that made him a genius.

“Da Vinci was illegitimate, homosexual, vegetarian, and left-handed.”

A culture that embraces differences creates genius.

Imagination and creativity are key qualities often required of those living in the present.

And we often mistakenly believe that it is just an individual ability.

But creativity thrives when people with diverse backgrounds come together, and innovation begins right there in the field.

Leonardo da Vinci always preferred to work with colleagues, students, and friends rather than alone, and whenever he didn't know something, he would always seek out someone more knowledgeable in that field and ask them questions.

“New ideas are often born in physical meeting places where people with diverse interests come together by chance.

So Steve Jobs created a central atrium in his building, and a young Benjamin Franklin opened a club where the most interesting people in Philadelphia gathered every Friday.

At the court of Ludovico Sforza, Leonardo found friends with whom he shared a variety of passions and who sparked new ideas.” —Chapter 8, “The Vitruvian Man,” p. 215

In Leonardo da Vinci's time, people from various professions worked closely together, and in their free time, it was common for them to flock to the square and discuss any topic.

The atmosphere that fuses ideas from disparate fields and encourages creativity is what made Leonardo da Vinci, Gutenberg, and Columbus possible.

Leonardo was a man with a charm that made one lovable.

He was “renowned not only for his talent but also for his handsome appearance, muscular physique, and affectionate nature,” and “dozens of prominent intellectuals of his time mention Leonardo as a dear and beloved friend in their letters.”

However, the conditions of his life were not all that favorable.

He was an illegitimate child, homosexual, and became a vegetarian after realizing that animals feel pain.

Also, because I valued rational thinking, I could not help but be heretical from a religious perspective.

But as mentioned before, he was universally loved and respected, and those in power supported him.

What is needed in modern times may be to properly learn the culture of the Renaissance.

A culture that respects each other's individuality and does not reject what is different, an attitude that there is something to learn from any field, and an atmosphere that tolerates reckless attempts to merge heterogeneous things.

In such a culture, geniuses are created, and our innovations continue to be renewed every day.

Steve Jobs, Bill Gates… Role models of the luminaries of the 21st century.

“The Secret to Creativity in Da Vinci’s 7,200-Page Notebook!”

A new book by Walter Isaacson, author of "Steve Jobs"!

Steve Jobs, who considered Leonardo da Vinci his hero,

Bill Gates bought a Da Vinci notebook for 34.9 billion won.

2019 marks the 500th anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci's death.

Born in Florence in 1452 and dying at the age of 67 in 1519, 500 years have passed since then, but Leonardo da Vinci's works and life still exert a powerful influence on people living in the 21st century.

Steve Jobs said that Leonardo “found beauty in both art and engineering, and his ability to bring the two together was what made him a genius.”

As is well known, Jobs rose to the top of the IT industry by combining new technologies with trendy designs.

Technology cannot advance without imagination.

Technology that lacks imagination attracts no one's attention.

Meanwhile, Bill Gates, who founded Microsoft, spent $30.8 million (approximately 34.9 billion won) on a 72-page set of Leonardo's notebooks (the 'Codex Leicester'), and commented, "Leonardo is the most fascinating person in history."

Leonardo da Vinci, the all-too-human genius

What is the secret to that creativity?

Walter Isaacson has presented a fascinating backstory of each of Leonardo da Vinci's works, and he also provides a wealth of information about the process of identifying Leonardo's authentic works.

However, among the numerous biographies of Leonardo da Vinci, Walter Isaacson's stands out because it presents 'Leonardo da Vinci the man.'

Bill Gates, who is so interested in Leonardo da Vinci that he owns his notebooks, known as the 'Codex Leicester,' said, "I've read quite a few books about Leonardo over the years.

“But I have never found a book that explores the other aspects of his life and work so well as to my satisfaction,” he said, recommending Isaacson’s biography, saying it “will show readers how human Leonardo was, and at the same time, how extraordinary he was.”

The New York Times also noted that while a common pitfall of biographies is defining their subjects as overly singular human beings, Isaacson "shines brightest when he talks about what makes Leonardo so human."

Leonardo is a genius.

However, rather than being a natural genius, he is a person who became a genius by solving his endless curiosity with imagination and effort.

Curiosity and imagination are inherent in all human beings.

However, it is like a muscle that deteriorates very easily if not used, so most people lose its function at a very young age.

Leonardo da Vinci was full of curiosity until the last moment of his life, and this is clearly evident in the voluminous notebooks he kept.

That's why Walter Isaacson focused on his notes.

He was a genius.

He was a man of unbridled imagination, burning curiosity, and creativity that encompassed a wide range of fields.

But we must use this expression carefully.

Labeling Leonardo a "genius" actually diminishes his value by making him into a special person who was struck by lightning.

(…) Leonardo's genius was human in nature and was accomplished through personal will and ambition.

He was not born with a superhuman brain like Newton or Einstein that ordinary humans cannot even fathom.

Leonardo had little formal education and could not read Latin or perform complex division.

His genius is of a kind we can fully understand, and even learn from.

It is based on abilities that we can improve ourselves, such as curiosity or keen observation.

Leonardo's unbridled imagination blurred the line between fantasy and fantasy, and this is something we can strive to protect ourselves and nurture in our children.

―From the preface

Leonardo da Vinci has impressed people around the world for centuries with his two famous works, “The Last Supper” and “Mona Lisa.”

But his work is not the product of what we usually call genius, an ability that comes without effort.

Masterpieces are created through constant curiosity, tireless observation and research, and boundless imagination.

As is well known, Leonardo left behind many unfinished works, but this cannot be attributed solely to his laziness.

He had no preconceptions, and because truth was always something new to be discovered, his work could only remain in the process of moving towards completion.

He constantly thought about the relationship between nature and humans, made rational judgments through scientific thinking, and boldly overturned religious thinking.

“Technology without imagination is barren.”

And there is no human being who does not imagine

It is no exaggeration to say that Leonardo lived several centuries ahead of his time.

He discovered, researched, and recorded the beginnings of innovation in various fields such as medicine, dentistry, anatomy, biology, geology, and physics.

He pioneered the scientific revolution a century before Galileo and pioneered the format of human anatomy diagrams used today.

He may be remembered as a pioneer in dentistry, as he was the first person in history to record in detail all the elements of a human tooth, and his notes also contain what may be the first case of arteriosclerosis described.

Leonardo also realized that the heart, not the liver, was the center of the blood system and figured out how the heart functions, but anatomists would not realize he was right until 450 years later.

One day, after seeing fossils of marine life in high altitude areas, he realized that the mountain ranges were formed by uplift of the earth's crust, and biogeography began in earnest 300 years later.

He also argued, contrary to common sense at the time, that embryos were still part of the mother's body, like the mother's hands and feet, and he also noticed that the moon did not emit light of its own but reflected sunlight.

Because his achievements were never officially announced or published, they had to wait anywhere from 100 years to 400 years for later innovators to rediscover them.

He delved into these many fields solely to satisfy his own curiosity.

Thanks to his study of perspective, he was able to dissect the human body and draw each body part in three dimensions on a two-dimensional plane. Through dissection, he realized that his earlier drawings of the muscles in the figures were incorrect and corrected them.

He meticulously dissected and observed the facial and lip muscles to identify the muscles that produce a smile, which likely contributed to creating the beautiful and mysterious smile of the Mona Lisa.

A masterpiece is completed at the tip of a genius's brush, but its seeds were already there in the artist's daily life, which he looked upon with wonder.

It was this attitude of looking at everything in the world with wonder that made him a genius.

“Da Vinci was illegitimate, homosexual, vegetarian, and left-handed.”

A culture that embraces differences creates genius.

Imagination and creativity are key qualities often required of those living in the present.

And we often mistakenly believe that it is just an individual ability.

But creativity thrives when people with diverse backgrounds come together, and innovation begins right there in the field.

Leonardo da Vinci always preferred to work with colleagues, students, and friends rather than alone, and whenever he didn't know something, he would always seek out someone more knowledgeable in that field and ask them questions.

“New ideas are often born in physical meeting places where people with diverse interests come together by chance.

So Steve Jobs created a central atrium in his building, and a young Benjamin Franklin opened a club where the most interesting people in Philadelphia gathered every Friday.

At the court of Ludovico Sforza, Leonardo found friends with whom he shared a variety of passions and who sparked new ideas.” —Chapter 8, “The Vitruvian Man,” p. 215

In Leonardo da Vinci's time, people from various professions worked closely together, and in their free time, it was common for them to flock to the square and discuss any topic.

The atmosphere that fuses ideas from disparate fields and encourages creativity is what made Leonardo da Vinci, Gutenberg, and Columbus possible.

Leonardo was a man with a charm that made one lovable.

He was “renowned not only for his talent but also for his handsome appearance, muscular physique, and affectionate nature,” and “dozens of prominent intellectuals of his time mention Leonardo as a dear and beloved friend in their letters.”

However, the conditions of his life were not all that favorable.

He was an illegitimate child, homosexual, and became a vegetarian after realizing that animals feel pain.

Also, because I valued rational thinking, I could not help but be heretical from a religious perspective.

But as mentioned before, he was universally loved and respected, and those in power supported him.

What is needed in modern times may be to properly learn the culture of the Renaissance.

A culture that respects each other's individuality and does not reject what is different, an attitude that there is something to learn from any field, and an atmosphere that tolerates reckless attempts to merge heterogeneous things.

In such a culture, geniuses are created, and our innovations continue to be renewed every day.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of publication: March 28, 2019

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 720 pages | 1,459g | 160*230*47mm

- ISBN13: 9788950980221

- ISBN10: 8950980223

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)