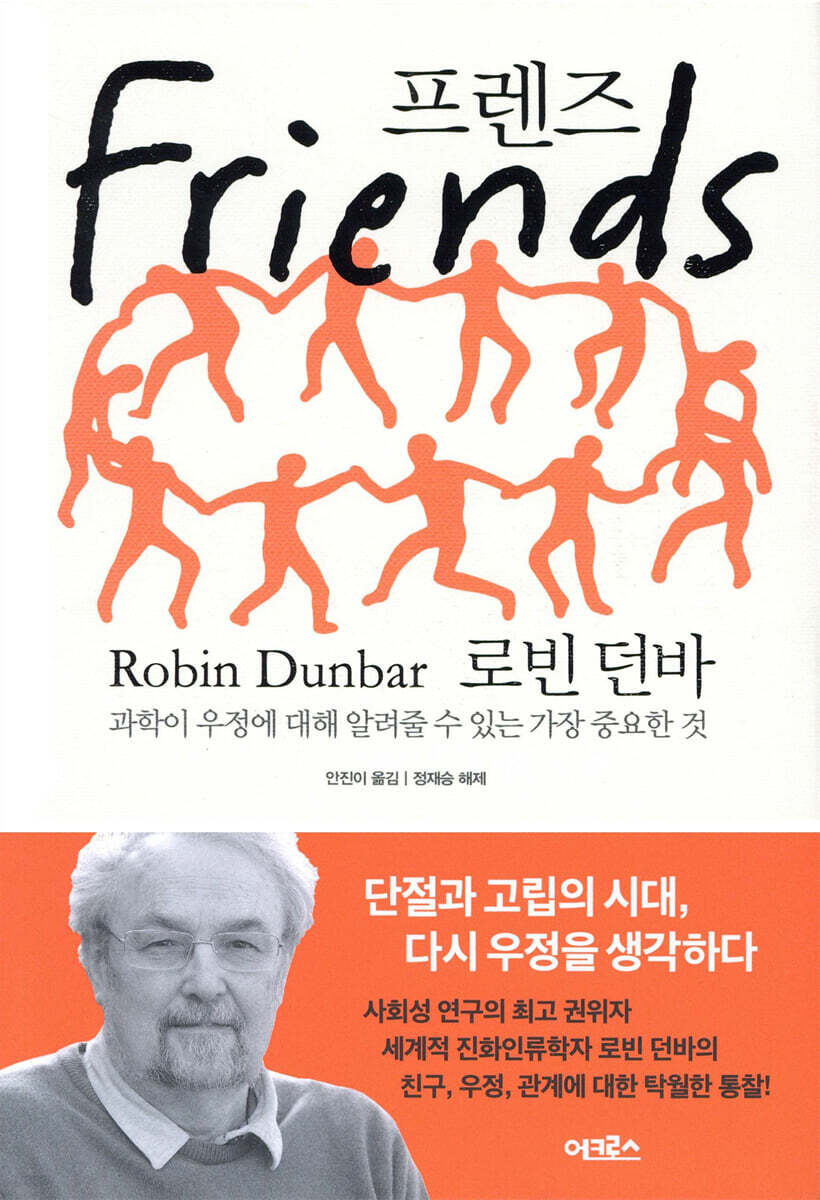

Friends

|

Description

Book Introduction

- A word from MD

-

The most precious value of friendship learned through scienceA scientific exploration of friendship from a leading authority on social studies.

A book that conveys the importance of friendship to those of us who are experiencing various social isolations, both online and offline.

From primate behavior to big data on mobile phones, we have comprehensively analyzed friendship, previously considered a subset of emotions, and provided scientific insights.

January 4, 2022. Natural Science PD Kim Yu-ri

The new book "Friends" by Oxford University professor Robin Dunbar, a leading authority on social studies, has been published.

In this scientific and original exploration of the origins, evolution, and value of friendship, Robin Dunbar explores why we make friends, how friendships begin and end, who we become friends with, how many friends we can have, and, most importantly, why friendship matters.

From research on the grooming of gelada baboons to cutting-edge research analyzing big data from mobile phone calls, the narrative weaves together a vast body of research, adding to the intellectual enjoyment. KAIST Professor Jaeseung Jeong's commentary provides a valuable guide for readers seeking to explore the world of friendship.

The Atlantic called the book "a timely arrival, a book that prompts reflection and reevaluation of friendship."

This is a book that is most needed now for modern people who are experiencing severe social isolation and disconnection due to the digital environment and the unprecedented spread of infectious diseases.

In this scientific and original exploration of the origins, evolution, and value of friendship, Robin Dunbar explores why we make friends, how friendships begin and end, who we become friends with, how many friends we can have, and, most importantly, why friendship matters.

From research on the grooming of gelada baboons to cutting-edge research analyzing big data from mobile phone calls, the narrative weaves together a vast body of research, adding to the intellectual enjoyment. KAIST Professor Jaeseung Jeong's commentary provides a valuable guide for readers seeking to explore the world of friendship.

The Atlantic called the book "a timely arrival, a book that prompts reflection and reevaluation of friendship."

This is a book that is most needed now for modern people who are experiencing severe social isolation and disconnection due to the digital environment and the unprecedented spread of infectious diseases.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Unlock: Everything We Want to Know About Friendship (Jeong Jae-seung)

At the beginning of the book

Chapter 1: Why Talk About Friendship Now?

Chapter 2 Dunbar's Number

Chapter 3 How Your Brain Makes Friends

Chapter 4: The Circle of Friendship

Chapter 5 Social Fingerprints

Chapter 6: Friendship and the Brain's Mechanisms

Chapter 7 The Magic of Time and Contact

Chapter 8: What Makes Friendship Strong

Chapter 9: The Language of Friendship

Chapter 10: The Seven Pillars of Homosexuality and Friendship

Chapter 11: Trust and Friendship

Chapter 12: What Can Romance Tell Us About Friendship?

Chapter 13: Friendship and Gender

Chapter 14: Why Did They Fall Away?

Chapter 15: Changes in Friendship with Age

Chapter 16: Friends Online

Further Reading

Search

At the beginning of the book

Chapter 1: Why Talk About Friendship Now?

Chapter 2 Dunbar's Number

Chapter 3 How Your Brain Makes Friends

Chapter 4: The Circle of Friendship

Chapter 5 Social Fingerprints

Chapter 6: Friendship and the Brain's Mechanisms

Chapter 7 The Magic of Time and Contact

Chapter 8: What Makes Friendship Strong

Chapter 9: The Language of Friendship

Chapter 10: The Seven Pillars of Homosexuality and Friendship

Chapter 11: Trust and Friendship

Chapter 12: What Can Romance Tell Us About Friendship?

Chapter 13: Friendship and Gender

Chapter 14: Why Did They Fall Away?

Chapter 15: Changes in Friendship with Age

Chapter 16: Friends Online

Further Reading

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

This book contains the true nature of friendship, something we have been so curious about, have thought of as important throughout our lives, and have sometimes relied on clumsily and sometimes excessively.

Why we make friends and why we need friendship, who we become friends with, how friendships are formed and when they break down—everything we want to know about friendship is contained in this book.

You made a very good choice.

--- p.7

In other words, the human community and social network of individuals usually consists of about 150 people.

These may seem like unrelated facts, but it's important to remember that before the advent of fast, inexpensive transportation about a century ago, people's social networks were essentially villages.

A person living then would have known a few people in the neighboring villages, and perhaps a cousin or uncle had 'friends' who commuted to the big city, but other than that, a person's social world was his or her village, and he or she shared that world with the other members of the village.

--- p.73

Time is a limited commodity, and the time we have available for social interaction follows a zero-sum law.

The time you give to one friend is time you cannot give to another friend.

What we know from studies of monkeys and humans is that the quality of a friendship is directly related to the amount of time invested in that relationship --- p.142

We need special abilities to deal with social complexity.

It is the ability to read and understand other people's minds.

This ability, called mindreading or mentalizing, is unique to humans.

Although some elements of this ability are found in some intelligent species of monkeys and apes, and their brains contain the neural circuits that underlie these abilities, only humans can use language, create fiction, and understand complex subjects like religion and science.

--- p.185

As humans evolved and the need arose to increase the size of our social groups, we had to find a way to increase the size of our grooming group proportionally to the size of the group.

As with other monkeys and apes, increasing the amount of time spent grooming was impossible for our ancestors (or us).

The only realistic way was to use our time more efficiently, and that was to groom multiple people at the same time.

--- p.253

The moment you open your mouth, I know through your dialect that you are a member of my community.

You are the one who knows the streets and bars that I know.

You know the jokes we used to tell over a pint of beer.

You are a person of the same religion as me.

All these clues form a simple and quick map that points to a common history, and anyone who has even one of these clues becomes a trustworthy person.

Because I know what kind of mindset you have.

These clues point to the fact that we grew up in the same neighborhood, adopted the same morals, and learned the same attitudes toward life and the world.

--- p.322

Digital media like Facebook may be good for maintaining friendships when we can't easily meet people.

But I feel like digital media only slows down the natural decay of friendships when they aren't constantly strengthened.

After all, unless you're truly close, nothing in the digital world can stop that friendship from quietly morphing into a relationship with someone you knew before (someone you knew before).

Why we make friends and why we need friendship, who we become friends with, how friendships are formed and when they break down—everything we want to know about friendship is contained in this book.

You made a very good choice.

--- p.7

In other words, the human community and social network of individuals usually consists of about 150 people.

These may seem like unrelated facts, but it's important to remember that before the advent of fast, inexpensive transportation about a century ago, people's social networks were essentially villages.

A person living then would have known a few people in the neighboring villages, and perhaps a cousin or uncle had 'friends' who commuted to the big city, but other than that, a person's social world was his or her village, and he or she shared that world with the other members of the village.

--- p.73

Time is a limited commodity, and the time we have available for social interaction follows a zero-sum law.

The time you give to one friend is time you cannot give to another friend.

What we know from studies of monkeys and humans is that the quality of a friendship is directly related to the amount of time invested in that relationship --- p.142

We need special abilities to deal with social complexity.

It is the ability to read and understand other people's minds.

This ability, called mindreading or mentalizing, is unique to humans.

Although some elements of this ability are found in some intelligent species of monkeys and apes, and their brains contain the neural circuits that underlie these abilities, only humans can use language, create fiction, and understand complex subjects like religion and science.

--- p.185

As humans evolved and the need arose to increase the size of our social groups, we had to find a way to increase the size of our grooming group proportionally to the size of the group.

As with other monkeys and apes, increasing the amount of time spent grooming was impossible for our ancestors (or us).

The only realistic way was to use our time more efficiently, and that was to groom multiple people at the same time.

--- p.253

The moment you open your mouth, I know through your dialect that you are a member of my community.

You are the one who knows the streets and bars that I know.

You know the jokes we used to tell over a pint of beer.

You are a person of the same religion as me.

All these clues form a simple and quick map that points to a common history, and anyone who has even one of these clues becomes a trustworthy person.

Because I know what kind of mindset you have.

These clues point to the fact that we grew up in the same neighborhood, adopted the same morals, and learned the same attitudes toward life and the world.

--- p.322

Digital media like Facebook may be good for maintaining friendships when we can't easily meet people.

But I feel like digital media only slows down the natural decay of friendships when they aren't constantly strengthened.

After all, unless you're truly close, nothing in the digital world can stop that friendship from quietly morphing into a relationship with someone you knew before (someone you knew before).

--- p.528

Publisher's Review

KAIST Professor Jaeseung Jeong's release and recommendation!

Robin Dunbar, a leading authority on social studies and Oxford scholar

The most scientific and original exploration of friends, friendship, and relationships.

Professor Robin Dunbar of Oxford University, a leading authority on social studies and widely known for his work on "Dunbar's Number," has published a new book, "Friends."

This book is a culmination of his research on 'sociality', to which he devoted most of his academic life, and stands out for its scientific and original exploration of the origins, evolution, and value of friendship.

In this book, Robin Dunbar takes a fascinating look at why we make friends, how friendships begin and end, who we become friends with, how many friends we can have, how our brains manage them, and most of all, why friendships matter.

Covering a wide range of disciplines, including psychology, anthropology, neuroscience, and genetics, it provides the most scientific answer to literally 'everything we want to know about friendship.'

From research on grooming in gelada baboons to cutting-edge research analyzing big data from mobile phone calls, the narrative weaves together a vast body of research, adding to the intellectual enjoyment. KAIST Professor Jaeseung Jeong's commentary, detailing the academic achievements of Robin Dunbar's research, the book's key content, and its significance, provides a valuable guide for readers exploring the world of friendship.

The Atlantic called the book "a timely arrival, a book that prompts reflection and reevaluation of friendship."

This book, brimming with brilliant insights into friendship, relationships, and friendships, is a much-needed read for modern people facing severe social isolation and disconnection due to the digital environment and the unprecedented spread of infectious diseases.

The most surprising facts revealed by medical research over the past 20 years

Friendship determines our life and death.

One of the most surprising findings from medical research over the past 20 years is that the more friends we have, the less sick we are and the longer we live.

In this book, Robin Dunbar presents various studies examining the impact of social relationships on our health, showing how valuable friends are and how genuine friendships contribute greatly to our health and happiness.

Robin Dunbar cites the research of Professor Julian Holt Runstad of Brigham Young University in the United States as a prime example.

Holt-Lunstad analyzed 148 epidemiological studies providing data on factors affecting mortality risk and found that the greatest influence on the study subjects' chances of survival was their level of social activity.

People who frequently received social support and who rated themselves as securely connected to their social networks and local communities had a 50 percent higher chance of survival.

On the other hand, people who feel alone or like outsiders experience extreme anxiety, which can have serious consequences for our health.

Robin Dunbar warns of the dangers of loneliness, citing research by Sarah Pressman and colleagues at Carnegie Mellon University.

Researchers found that college freshmen who felt lonely had a reduced immune response to the flu vaccine.

The immune systems of freshmen who felt lonely were weakened and did not mount an adequate level of immune response to the vaccine's penetration.

In other words, even though they were vaccinated, they were not very good at preventing the flu virus from entering the country.

Even from the perspective of the physiological functioning of the immune system, we can see that friendship and bonding play an extremely beneficial role for us.

In addition, this book presents various studies that show that friendship actually helps our health and survival.

This reflects the reality that, as KAIST Professor Jaeseung Jeong mentioned in the introduction to this book, “recently, scholars have paid special academic attention to the relationship called ‘friendship’ among human relationships” and have begun to seriously explore it.

And this book is even more special because “Robin Dunbar, a world authority on friendship and one of the longest-standing researchers, shares the core findings of his research.”

Who is my best friend? How many friends can I have?

The Secrets of Social Relationships: Dunbar's Number and the Circle of Friendship

Robin Dunbar, based on his studies of primates and comparing humans with other great apes, proposed a bold hypothesis called the "social brain hypothesis" (that an animal's brain size determines the size of its social group, or more precisely, that brain size constrains the size of its social group).

In particular, it was argued that the human brain has evolved to process social information, and therefore the size and capacity of the brain can be used to predict the scale of human relationships.

That number is '150 people', and this is what we all know as 'Dunbar's number'.

According to Dunbar, these 150 people are people you know well enough to “spot them in an airport lounge and not hesitate to go up and sit next to them.”

In fact, these 150 people are one of the layers of the 'Circle of Friendship' discovered by Robin Dunbar.

Dunbar analyzed data on the size of small societies and found that several social strata formed a fairly distinct chain of about 5, 15, 50, 150, 500, and 1,500 people, with each stratum sequentially subsumed by the next.

According to Dunbar, if we were to describe these circles in everyday terms, a circle of five people would be "close friends," a circle of 15 people would be "close friends," a circle of 50 people would be "good friends," and a circle of 150 people would be "just friends."

The 500 people were categorized as 'acquaintances (people I work with or just know)', and the 1,500 people were categorized as 'people I only know by name'.

Each circle (or layer) is associated with a specific frequency of contact, emotional closeness, and willingness to help.

When we step outside the circles representing our significant friends (150 floors), our willingness to act altruistically changes dramatically.

We have little desire to help those in this outer circle.

Even if they help, they act based on thorough reciprocity.

When we help 150 friends, we don't necessarily expect anything in return.

When I help my very close friends, I don't expect anything in return.

In this way, our 'friendship circle' plays a crucial role in giving us a quick overview of our social network: who we can lean on for a cry, who we can have dinner with and go to the movies with on a regular basis, and who we will invite to our wedding.

Dunbar's Number Still Works Online

Why We Need to Rethink Friendship Now

What's most interesting about this book is that it argues that Dunbar's number of 150 people still holds true in the age of social media.

Many people believe that the number of friends they have has expanded significantly thanks to the use of social media such as Twitter and Facebook, but the number of friends they talk to and socialize with is still between 150 and 250.

Robin Dunbar mentions a very interesting case in the text.

A famous TV host with a huge following went to each of his Facebook friends to verify whether Dunbar's number actually worked.

There was even a case where he showed up at someone's wedding without being invited.

As a result, the people who welcomed him were people he already knew or people within his social circle.

The rest of the people mostly expressed surprise rather than joy, some seemed uncomfortable with his visit, and some even turned him away.

Other studies that have demonstrated that Dunbar's number holds true in the online world include a study that examined the impact of social media use on the size of social networks among Dutch university students, a study by software engineers that collected and graphed the number of friends publicly disclosed on Facebook, and a study that analyzed email patterns sent by faculty and students at the University of Oslo.

(Pages 74-77)

Robin Dunbar argues that even in the age of the Internet and mobile devices, human social relationships cannot expand infinitely and are governed by the capacity of the social brain.

He observed that new friends made on social networking sites are usually for the sites' advertising revenue, and that the majority of people who use SNS prioritize maintaining or strengthening relationships with existing friends.

Robin Dunbar sees social networking sites and new forms of social media as helping to maintain friendships that might otherwise have faded due to the lack of face-to-face contact.

However, concerns are raised about the fact that most online interactions are one-on-one rather than group interactions, and that when problems arise in relationships with others, people end the relationship by disconnecting rather than compromising.

He warns that continuing to communicate in this way, especially as children get younger, will hinder their social skills and make it difficult to deal with rejection, aggression, and failure.

Even today, when virtual encounters have become commonplace, Robin Dunbar reiterates that direct communication, socializing, light physical contact, conversation, and chatting are still the most important ways to make and maintain valuable friends.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: January 3, 2022

- Page count, weight, size: 584 pages | 852g | 150*217*35mm

- ISBN13: 9791167740250

- ISBN10: 1167740254

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)