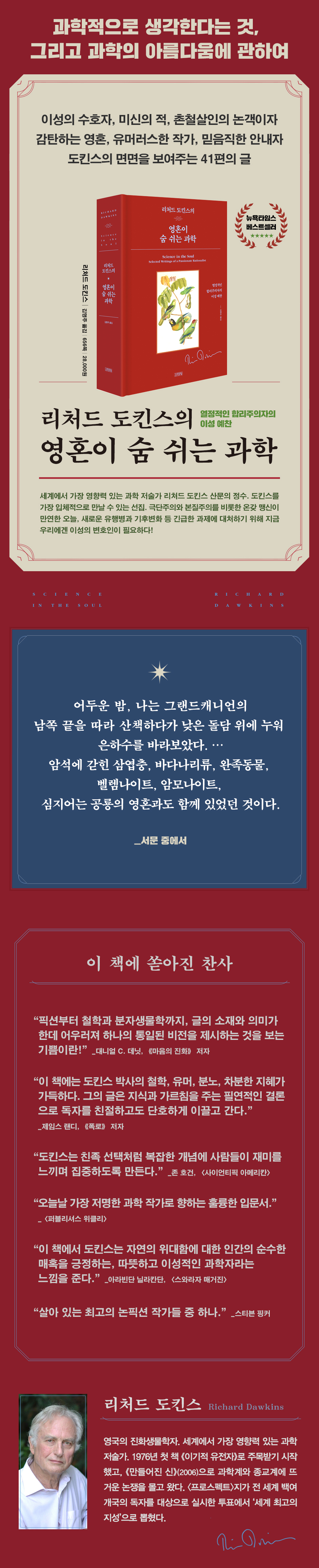

Richard Dawkins's Science with a Breath of Spirit

|

Description

Book Introduction

The guardian of reason, the enemy of superstition, and the sharp-tongued debater.

An admirable soul, a humorous writer, a trustworthy guide.

41 essays showcasing Dawkins' diverse perspectives

A collection of 41 lectures, columns, and essays written over 30 years, including Dawkins' first published writings in the United States.

This is an anthology that provides the most three-dimensional glimpse into the human being Richard Dawkins, and is “a must-have for any Dawkins fan” (Kirkus Review).

What has Dawkins, one of the world's most influential science writers and evolutionary biologists, researched, written, and spoken about? And what does it mean to him to live as a scientist, a rational member of society, a global citizen and Earthling, and even as someone's disciple or family member? This book answers these questions by covering a wide range of topics, from Dawkins's usual topics (evolution, natural selection, religion, and the philosophy of science) to political, social, cultural, and personal issues, in a variety of formats.

Readers who know Richard Dawkins only through The Selfish Gene and as an aggressive atheist will see a different side of him through this book.

An admirable soul, a humorous writer, a trustworthy guide.

41 essays showcasing Dawkins' diverse perspectives

A collection of 41 lectures, columns, and essays written over 30 years, including Dawkins' first published writings in the United States.

This is an anthology that provides the most three-dimensional glimpse into the human being Richard Dawkins, and is “a must-have for any Dawkins fan” (Kirkus Review).

What has Dawkins, one of the world's most influential science writers and evolutionary biologists, researched, written, and spoken about? And what does it mean to him to live as a scientist, a rational member of society, a global citizen and Earthling, and even as someone's disciple or family member? This book answers these questions by covering a wide range of topics, from Dawkins's usual topics (evolution, natural selection, religion, and the philosophy of science) to political, social, cultural, and personal issues, in a variety of formats.

Readers who know Richard Dawkins only through The Selfish Gene and as an aggressive atheist will see a different side of him through this book.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Author's Preface

Editor's Preface

Part 1: The Values of Science

The values of science and the science of values

In Defense of Science: An Open Letter to Prince Charles

Science and Sensitivity

Doolittle and Darwin

Part 2: The Ultimate in Mercilessness

"More Darwinian than Darwin": The Darwin and Wallace Papers

Universal Darwinism

Ecosystem of self-replicators

Twelve Misconceptions About Kin Selection

Part 3: Family Law Future

net profit

intelligent aliens

Look under the streetlight

50 Years Later: Killing the Soul?

Part 4: Mental Control, Root Causes, and Confusion

Alabama's Embedded Document

guided missiles of 9/11

Theology of Tsunami

Merry Christmas, Prime Minister!

The Science of Religion

Is science a religion?

Atheist who supports Jesus

Part 5: Living in the Real World

Plato's Yoke

'So that there is no reasonable doubt'?

But do they feel pain?

I like fireworks, but… …

Who is holding a rally against reason?

Praise for subtitles, criticism of dubbing

If I ruled the world

Part 6: The Sacred Truth of Nature

About time

The Giant Tortoise Tale: An Island Within an Island

Sea Turtle Tales: Back There (and Back Again?)

Saying goodbye to the dreamy digital elite

Part 7: Laughing at the Living Dragon

Fundraising for Faith

The Amazing Bus Mystery

Jarvis and the phylogenetic tree

Gerin Oil

The wise elder leader of dinosaur enthusiasts

Mutoron: I hope this trend continues for a long time.

Dawkins' Law

Part 8: No Man is an Island

Memories of the Maestro

Oh, My Beloved Father: John Dawkins, 1915–2010

More than just an uncle: A.

F. 'Bill' Dawkins, 1916–2009

In tribute to Hitchens

Translator's Note

Source and Acknowledgements

Cited References

Search

Editor's Preface

Part 1: The Values of Science

The values of science and the science of values

In Defense of Science: An Open Letter to Prince Charles

Science and Sensitivity

Doolittle and Darwin

Part 2: The Ultimate in Mercilessness

"More Darwinian than Darwin": The Darwin and Wallace Papers

Universal Darwinism

Ecosystem of self-replicators

Twelve Misconceptions About Kin Selection

Part 3: Family Law Future

net profit

intelligent aliens

Look under the streetlight

50 Years Later: Killing the Soul?

Part 4: Mental Control, Root Causes, and Confusion

Alabama's Embedded Document

guided missiles of 9/11

Theology of Tsunami

Merry Christmas, Prime Minister!

The Science of Religion

Is science a religion?

Atheist who supports Jesus

Part 5: Living in the Real World

Plato's Yoke

'So that there is no reasonable doubt'?

But do they feel pain?

I like fireworks, but… …

Who is holding a rally against reason?

Praise for subtitles, criticism of dubbing

If I ruled the world

Part 6: The Sacred Truth of Nature

About time

The Giant Tortoise Tale: An Island Within an Island

Sea Turtle Tales: Back There (and Back Again?)

Saying goodbye to the dreamy digital elite

Part 7: Laughing at the Living Dragon

Fundraising for Faith

The Amazing Bus Mystery

Jarvis and the phylogenetic tree

Gerin Oil

The wise elder leader of dinosaur enthusiasts

Mutoron: I hope this trend continues for a long time.

Dawkins' Law

Part 8: No Man is an Island

Memories of the Maestro

Oh, My Beloved Father: John Dawkins, 1915–2010

More than just an uncle: A.

F. 'Bill' Dawkins, 1916–2009

In tribute to Hitchens

Translator's Note

Source and Acknowledgements

Cited References

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

Instinctive emotions, even if they don't spring from the murky waters of xenophobia, misogyny, or other blind prejudices, should not enter the polls.

Until now, such dark feelings have largely remained beneath the surface.

But the political movements of 2016 on both sides of the Atlantic brought those feelings to the surface, allowing them to be expressed, if not respected, then at least publicly.

For half a century, people have been ashamed of their prejudices and have hidden them from view, but now, agitators are taking the lead and declaring that they can express them.

--- p.19~20, from the author's preface

…Why doesn't natural selection create bones so thick they can never break? We humans can, through artificial selection, create dog breeds with leg bones so strong they can never break.

Why doesn't nature do something like this? It's because of the cost, which implies a value system.

We don't ask engineers and architects to create unbreakable structures or impenetrable walls.

Instead, we give them a budget and ask them to do their best within certain constraints and meet the standards.

…

…Darwinian selection also pursues the optimum within economic limits, and in that sense, it can be said to have values.

John Maynard Smith said:

“If there were no constraints on what was possible, the best phenotype would live forever, never be eaten by predators, and lay eggs indefinitely.”

--- p.73~75, from “The Values of Science and the Science of Values”

If you protest such talk, you will be accused of being 'elitist'.

That's a bad word.

But what if that wasn't such a bad thing? While exclusive superiority complex isn't something to be dismissed, efforts to help people raise their standards and solidify the elite are a completely different matter.

The worst thing you can do is deliberately lower your standards.

It is an attitude of looking down on the other person as if you are doing them a favor.

…

…true science may be difficult, but like classical literature and violin playing, it is worth the effort.

--- p.126~127, from “Science and Sensibility”

Darwin and Wallace may not have been the first to have a vague idea of this.

But they were the first to understand that the problem was important, and that the solution they came up with separately and simultaneously was equally important.

This shows their level as scientists.

And the mutual tolerance they displayed in resolving the priority issue shows their level of humanity.

--- p.188, from “More Darwinian than Darwin”

Just as Darwin destroyed the mystical 'design' argument in the mid-19th century, and just as Watson and Crick destroyed all the mystical nonsense about genes in the mid-20th century, their successors in the mid-21st century will destroy the mystical absurdity of the soul being separated from the body.

…we do not understand consciousness.

Not yet.

But I believe we will understand before 2057.

And if that happens, it will undoubtedly be scientists, not mystics or theologians, who will solve this greatest riddle.

He may be a solitary genius like Darwin, but he is more likely to be a union of neuroscientists, computer scientists, and science-savvy philosophers.

At that time, Soul-1 will meet an untimely death at the hands of science, and in the process, Soul-2 will ascend to heights that no one could have imagined.

--- p.329~330, from “50 Years Later: Killing the Soul?”

“What is the survival of religion?” may be the wrong question.

The right question should be:

Only by rephrasing the question, “What is the survival value of some individual behavior or psychological trait, not yet specifically identified, that manifests itself as religion in appropriate circumstances?” can we find a reasonable answer.

--- p.388, from “The Science of Religion”

Essentialism confuses ethical debates such as abortion and euthanasia.

At what point in a brain-dead accident can a victim be defined as "dead"? At what point in development does a fetus become a "person"? Only a mind infected with essentialism would ask such questions.

Because an embryo develops gradually from a single-celled zygote into a newborn, there is no single moment that can be considered a 'human existence'.

The world is divided between those who understand this fact and those who plead, “But isn’t there a moment when the fetus becomes a human being?”

no.

Such moments do not actually exist.

It's like there's no day when a middle-aged person becomes old.

Although not ideal, it is better to say that the fetus goes through stages such as one-quarter human, one-half human, three-quarters human, etc.

The essentialist mind avoids such expressions and uses all sorts of threats to accuse me of denying the essence of humanity.

--- p.437~438, from “Plato’s Yoke”

Every page of this book sparkles with science, scientific wit, and science seen through the rainbow prism of a "first-rate imagination."

There is no trace of jaded sentimentality in Douglas's views of aye-ayes, kakapo, northern white rhinoceros, eko-parrots, or Komodo dragons.

Douglas understood well how slowly the millstone of natural selection turns.

He knew that it took millions of years for a mountain gorilla, a pink pigeon, or a Yangtze River dolphin to form.

He saw with his own eyes that such elaborate creatures, painstakingly crafted by evolution, could crumble in an instant and disappear into oblivion.

And he tried to do something about it.

We should do that too.

If only to commemorate a specimen that will never be repeated in Homo sapiens.

This time, I think they named it Homo sapiens well.

--- p.529, from "Farewell to the Dreaming Digital Elite"

Dawkins's "New Irrefutable Law"

God cannot be defeated.

Auxiliary Theorem 1: As understanding expands, God contracts.

But God then redefines himself and restores the phenomenon.

Auxiliary Theorem 2: When things go well, God gets the thanks.

When things go wrong, God is thanked for not making things worse.

Auxiliary Theorem 3: Belief in an afterlife can only be proven true, never false.

Auxiliary Theorem 4: The vehemence with which an unprovable belief is defended is inversely proportional to its defensibility.

--- p.581, from "Dawkins' Law"

In his newly written preface to this book, Dawkins writes, "Isn't science, beyond being the inspiration for great works of literature, a worthy subject for the best writers in its own right? And isn't the very quality that makes science so perhaps the closest thing to the meaning of 'soul'?" He writes that it's time for a scientist to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature.

The scientists he cited as worthy of such a title are, unfortunately, already deceased. But as Skeptic editor Michael Shermer, who singled out Dawkins as a Nobel Prize-worthy scientist, suggests, wouldn't Dawkins be able to do it? He's one of the few writers who can infuse a science book with not only information and entertainment, but also emotion, beauty, and even "soul."

Until now, such dark feelings have largely remained beneath the surface.

But the political movements of 2016 on both sides of the Atlantic brought those feelings to the surface, allowing them to be expressed, if not respected, then at least publicly.

For half a century, people have been ashamed of their prejudices and have hidden them from view, but now, agitators are taking the lead and declaring that they can express them.

--- p.19~20, from the author's preface

…Why doesn't natural selection create bones so thick they can never break? We humans can, through artificial selection, create dog breeds with leg bones so strong they can never break.

Why doesn't nature do something like this? It's because of the cost, which implies a value system.

We don't ask engineers and architects to create unbreakable structures or impenetrable walls.

Instead, we give them a budget and ask them to do their best within certain constraints and meet the standards.

…

…Darwinian selection also pursues the optimum within economic limits, and in that sense, it can be said to have values.

John Maynard Smith said:

“If there were no constraints on what was possible, the best phenotype would live forever, never be eaten by predators, and lay eggs indefinitely.”

--- p.73~75, from “The Values of Science and the Science of Values”

If you protest such talk, you will be accused of being 'elitist'.

That's a bad word.

But what if that wasn't such a bad thing? While exclusive superiority complex isn't something to be dismissed, efforts to help people raise their standards and solidify the elite are a completely different matter.

The worst thing you can do is deliberately lower your standards.

It is an attitude of looking down on the other person as if you are doing them a favor.

…

…true science may be difficult, but like classical literature and violin playing, it is worth the effort.

--- p.126~127, from “Science and Sensibility”

Darwin and Wallace may not have been the first to have a vague idea of this.

But they were the first to understand that the problem was important, and that the solution they came up with separately and simultaneously was equally important.

This shows their level as scientists.

And the mutual tolerance they displayed in resolving the priority issue shows their level of humanity.

--- p.188, from “More Darwinian than Darwin”

Just as Darwin destroyed the mystical 'design' argument in the mid-19th century, and just as Watson and Crick destroyed all the mystical nonsense about genes in the mid-20th century, their successors in the mid-21st century will destroy the mystical absurdity of the soul being separated from the body.

…we do not understand consciousness.

Not yet.

But I believe we will understand before 2057.

And if that happens, it will undoubtedly be scientists, not mystics or theologians, who will solve this greatest riddle.

He may be a solitary genius like Darwin, but he is more likely to be a union of neuroscientists, computer scientists, and science-savvy philosophers.

At that time, Soul-1 will meet an untimely death at the hands of science, and in the process, Soul-2 will ascend to heights that no one could have imagined.

--- p.329~330, from “50 Years Later: Killing the Soul?”

“What is the survival of religion?” may be the wrong question.

The right question should be:

Only by rephrasing the question, “What is the survival value of some individual behavior or psychological trait, not yet specifically identified, that manifests itself as religion in appropriate circumstances?” can we find a reasonable answer.

--- p.388, from “The Science of Religion”

Essentialism confuses ethical debates such as abortion and euthanasia.

At what point in a brain-dead accident can a victim be defined as "dead"? At what point in development does a fetus become a "person"? Only a mind infected with essentialism would ask such questions.

Because an embryo develops gradually from a single-celled zygote into a newborn, there is no single moment that can be considered a 'human existence'.

The world is divided between those who understand this fact and those who plead, “But isn’t there a moment when the fetus becomes a human being?”

no.

Such moments do not actually exist.

It's like there's no day when a middle-aged person becomes old.

Although not ideal, it is better to say that the fetus goes through stages such as one-quarter human, one-half human, three-quarters human, etc.

The essentialist mind avoids such expressions and uses all sorts of threats to accuse me of denying the essence of humanity.

--- p.437~438, from “Plato’s Yoke”

Every page of this book sparkles with science, scientific wit, and science seen through the rainbow prism of a "first-rate imagination."

There is no trace of jaded sentimentality in Douglas's views of aye-ayes, kakapo, northern white rhinoceros, eko-parrots, or Komodo dragons.

Douglas understood well how slowly the millstone of natural selection turns.

He knew that it took millions of years for a mountain gorilla, a pink pigeon, or a Yangtze River dolphin to form.

He saw with his own eyes that such elaborate creatures, painstakingly crafted by evolution, could crumble in an instant and disappear into oblivion.

And he tried to do something about it.

We should do that too.

If only to commemorate a specimen that will never be repeated in Homo sapiens.

This time, I think they named it Homo sapiens well.

--- p.529, from "Farewell to the Dreaming Digital Elite"

Dawkins's "New Irrefutable Law"

God cannot be defeated.

Auxiliary Theorem 1: As understanding expands, God contracts.

But God then redefines himself and restores the phenomenon.

Auxiliary Theorem 2: When things go well, God gets the thanks.

When things go wrong, God is thanked for not making things worse.

Auxiliary Theorem 3: Belief in an afterlife can only be proven true, never false.

Auxiliary Theorem 4: The vehemence with which an unprovable belief is defended is inversely proportional to its defensibility.

--- p.581, from "Dawkins' Law"

In his newly written preface to this book, Dawkins writes, "Isn't science, beyond being the inspiration for great works of literature, a worthy subject for the best writers in its own right? And isn't the very quality that makes science so perhaps the closest thing to the meaning of 'soul'?" He writes that it's time for a scientist to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature.

The scientists he cited as worthy of such a title are, unfortunately, already deceased. But as Skeptic editor Michael Shermer, who singled out Dawkins as a Nobel Prize-worthy scientist, suggests, wouldn't Dawkins be able to do it? He's one of the few writers who can infuse a science book with not only information and entertainment, but also emotion, beauty, and even "soul."

--- p.628, from the “Translator’s Note”

Publisher's Review

The guardian of reason, the enemy of superstition, and the sharp-tongued debater.

An admirable soul, a humorous writer, a trustworthy guide.

41 essays showcasing Dawkins' diverse perspectives

★★★ New York Times Bestseller ★★★

“A must-have for any Dawkins fan.”_Kirkus Reviews

The Essence of Prose by Richard Dawkins, the World's Most Influential Science Writer

An anthology that provides the most three-dimensional encounter with Dawkins.

Dawkins' new collection of essays, "The Science of Life," has been published.

For decades, Dawkins has been one of the most prominent science writers, constantly revealing the mysteries of nature and attacking flawed logic.

The writings contained here all embody Dawkins's characteristic erudition, wit, and ever-new sense of wonder about nature.

“This book is Richard Dawkins’ second collection of essays after The Devil’s Apostle (2003).

This book is a compilation of 41 short and long essays, divided into eight parts, selected in collaboration with editor Gillian Somerscales, who worked on The God Delusion.

The writing period spans 30 years, most of which was written while he was the Charles Simonyi Professor for the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University from 1995 to 2009.

Not only the time of writing, but also the venues where each manuscript was presented varied, including lectures, event opening ceremonies, various media outlets, funerals, and memorial services.

The topics covered range from the complex theory of evolution to the values of scientists, religion, future predictions, and personal lives.

The result is a fascinating portrait of Dawkins, one not found in other books.

“Although he already has a two-volume autobiography published, this collection of writings reads in a sense as another biography.” (Translator’s Note) Readers who only knew Richard Dawkins as The Selfish Gene and an aggressive atheist will see a different side of him through this book.

Still, in an age when science is needed more than ever,

Speaking of 'science with a living soul'

Although these writings span over 30 years, they are no less timely or urgent now.

Politicians have opened the floodgates to prejudices that have been unacceptable, or at least not openly discussed, for half a century.

In his passionate introduction, Dawkins argues that reason must reign supreme and that “gut feelings, even if they do not spring from the murky mire of xenophobia, misogyny, or other blind prejudices, have no place in the voting booth.”

And in his newly annotated essays, Dawkins criticizes bad science, religious education, and climate change deniers, covering a range of topics, including the importance of verifiable evidence.

But his science is not entirely merciless.

The word 'soul' in the title was also included by Dawkins to emphasize that it is not a word that should be used only in non-scientific areas.

He argues throughout this book that while neither we nor science have ghostly souls, they can have souls in the sense of expressing 'something beyond reality', 'something wonderful and beautiful', and 'emotional qualities', and in that sense, science has a soul more than any superstitious thing, including religion.

Letters, fiction, opening remarks, eulogies, lectures, and even newly added annotations and reviews.

A book that comprehensively presents Dawkins as a scientist, citizen, and human being through writings of various formats and contents.

This book shows many different sides of Dawkins, but at its center is Dawkins as a scientist.

Part 1 directly deals with Dawkins' philosophy of science, and throughout this chapter, you can hear Dawkins' answer to the question, "What is science?"

Part 2 examines how Darwin's great theory developed and was refined.

Through these essays, readers will learn “how the theory began with the rare gentlemanly actions of two scientists, how it works, how far its power and validity extend, how it has developed and how it has been misunderstood.”

Part 3, titled "Science as a Prophet of Reason," offers a multifaceted outlook on the future brought about by scientific progress, including advancements in space exploration technology and consciousness research.

Afterwards, we meet Dawkins, a commentator who speaks on more specific issues.

Part 4 consists of essays that present Dawkins's positions on current issues, most of which contain strong criticisms of irrational claims involving religion.

Part 5 contains articles about the contradictions felt when observing modern culture.

It covers everything from fundamentalist thinking, black-and-white thinking, and bureaucracy to the overlooking of animal suffering when setting off fireworks and the regret of using dubbing instead of subtitles on the news.

In the latter part of the book, we meet a more "human" Dawkins, who marvels at nature, cracks cheeky jokes, and reflects on the adults in his life.

Part 6 features essays that celebrate the truths that emerge from observations of the majestic and complex natural world.

It explores vast geological timescales, including the curious history of giant tortoises and sea turtles.

Through their journey between water and land, readers will gain a deeper understanding of evolution.

Part 7 focuses on Dawkins as a humorist.

It is a collection of 'non-formal' writings, such as fiction and parodies about fictional characters or objects.

Part 8 contains a collection of writings by Dawkins about people he admires, revealing the greatness of a human being.

As the translator notes, “His warm and delightful writings about his teachers, colleagues, and family shine beautifully with his pride in the collaborative enterprise of science, the ‘warmth of human affection,’ and his longing for the souls that made him who he is.”

The main text of this book has two visually striking features: the footnotes are designed to be larger than usual, and most text is followed by an "afterword."

This is for the reasons Dawkins explains in his preface:

“Updates to information were limited to footnotes and afterwords.

Reading these brief supplements and reflections alongside the main text will feel like a conversation between me today and the author of the original manuscript.

To aid this reading, the footnotes are set in a larger font than is customary in academic texts, such as footnotes or endnotes.” Although the essays in this book were written over a period of up to 30 years, the fresh impressions and backstories that Dawkins added through footnotes and afterwords while compiling the book will allow for a richer reading experience by showing the life of the essays that continues even after their ‘publication. ’

“A must-have for any Dawkins fan.”_Kirkus Reviews

“An excellent introduction to one of today's most prominent science writers.” —Publisher's Weekly

“These 41 essays accurately capture the reputation that evolutionary biologist Dawkins has earned as a ‘ruthless advocate of rationalism.’

He has a scientific attitude that is engaging and questioning, and a sharp wit.”_〈Library Journal〉

“It’s intense.

…presents remarkably sharp and convincing opinions.

… [Richard Dawkins] is the scholar who has contributed most to the popularization of science in the past half-century.” _〈Christian Science Monitor〉

An admirable soul, a humorous writer, a trustworthy guide.

41 essays showcasing Dawkins' diverse perspectives

★★★ New York Times Bestseller ★★★

“A must-have for any Dawkins fan.”_Kirkus Reviews

The Essence of Prose by Richard Dawkins, the World's Most Influential Science Writer

An anthology that provides the most three-dimensional encounter with Dawkins.

Dawkins' new collection of essays, "The Science of Life," has been published.

For decades, Dawkins has been one of the most prominent science writers, constantly revealing the mysteries of nature and attacking flawed logic.

The writings contained here all embody Dawkins's characteristic erudition, wit, and ever-new sense of wonder about nature.

“This book is Richard Dawkins’ second collection of essays after The Devil’s Apostle (2003).

This book is a compilation of 41 short and long essays, divided into eight parts, selected in collaboration with editor Gillian Somerscales, who worked on The God Delusion.

The writing period spans 30 years, most of which was written while he was the Charles Simonyi Professor for the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University from 1995 to 2009.

Not only the time of writing, but also the venues where each manuscript was presented varied, including lectures, event opening ceremonies, various media outlets, funerals, and memorial services.

The topics covered range from the complex theory of evolution to the values of scientists, religion, future predictions, and personal lives.

The result is a fascinating portrait of Dawkins, one not found in other books.

“Although he already has a two-volume autobiography published, this collection of writings reads in a sense as another biography.” (Translator’s Note) Readers who only knew Richard Dawkins as The Selfish Gene and an aggressive atheist will see a different side of him through this book.

Still, in an age when science is needed more than ever,

Speaking of 'science with a living soul'

Although these writings span over 30 years, they are no less timely or urgent now.

Politicians have opened the floodgates to prejudices that have been unacceptable, or at least not openly discussed, for half a century.

In his passionate introduction, Dawkins argues that reason must reign supreme and that “gut feelings, even if they do not spring from the murky mire of xenophobia, misogyny, or other blind prejudices, have no place in the voting booth.”

And in his newly annotated essays, Dawkins criticizes bad science, religious education, and climate change deniers, covering a range of topics, including the importance of verifiable evidence.

But his science is not entirely merciless.

The word 'soul' in the title was also included by Dawkins to emphasize that it is not a word that should be used only in non-scientific areas.

He argues throughout this book that while neither we nor science have ghostly souls, they can have souls in the sense of expressing 'something beyond reality', 'something wonderful and beautiful', and 'emotional qualities', and in that sense, science has a soul more than any superstitious thing, including religion.

Letters, fiction, opening remarks, eulogies, lectures, and even newly added annotations and reviews.

A book that comprehensively presents Dawkins as a scientist, citizen, and human being through writings of various formats and contents.

This book shows many different sides of Dawkins, but at its center is Dawkins as a scientist.

Part 1 directly deals with Dawkins' philosophy of science, and throughout this chapter, you can hear Dawkins' answer to the question, "What is science?"

Part 2 examines how Darwin's great theory developed and was refined.

Through these essays, readers will learn “how the theory began with the rare gentlemanly actions of two scientists, how it works, how far its power and validity extend, how it has developed and how it has been misunderstood.”

Part 3, titled "Science as a Prophet of Reason," offers a multifaceted outlook on the future brought about by scientific progress, including advancements in space exploration technology and consciousness research.

Afterwards, we meet Dawkins, a commentator who speaks on more specific issues.

Part 4 consists of essays that present Dawkins's positions on current issues, most of which contain strong criticisms of irrational claims involving religion.

Part 5 contains articles about the contradictions felt when observing modern culture.

It covers everything from fundamentalist thinking, black-and-white thinking, and bureaucracy to the overlooking of animal suffering when setting off fireworks and the regret of using dubbing instead of subtitles on the news.

In the latter part of the book, we meet a more "human" Dawkins, who marvels at nature, cracks cheeky jokes, and reflects on the adults in his life.

Part 6 features essays that celebrate the truths that emerge from observations of the majestic and complex natural world.

It explores vast geological timescales, including the curious history of giant tortoises and sea turtles.

Through their journey between water and land, readers will gain a deeper understanding of evolution.

Part 7 focuses on Dawkins as a humorist.

It is a collection of 'non-formal' writings, such as fiction and parodies about fictional characters or objects.

Part 8 contains a collection of writings by Dawkins about people he admires, revealing the greatness of a human being.

As the translator notes, “His warm and delightful writings about his teachers, colleagues, and family shine beautifully with his pride in the collaborative enterprise of science, the ‘warmth of human affection,’ and his longing for the souls that made him who he is.”

The main text of this book has two visually striking features: the footnotes are designed to be larger than usual, and most text is followed by an "afterword."

This is for the reasons Dawkins explains in his preface:

“Updates to information were limited to footnotes and afterwords.

Reading these brief supplements and reflections alongside the main text will feel like a conversation between me today and the author of the original manuscript.

To aid this reading, the footnotes are set in a larger font than is customary in academic texts, such as footnotes or endnotes.” Although the essays in this book were written over a period of up to 30 years, the fresh impressions and backstories that Dawkins added through footnotes and afterwords while compiling the book will allow for a richer reading experience by showing the life of the essays that continues even after their ‘publication. ’

“A must-have for any Dawkins fan.”_Kirkus Reviews

“An excellent introduction to one of today's most prominent science writers.” —Publisher's Weekly

“These 41 essays accurately capture the reputation that evolutionary biologist Dawkins has earned as a ‘ruthless advocate of rationalism.’

He has a scientific attitude that is engaging and questioning, and a sharp wit.”_〈Library Journal〉

“It’s intense.

…presents remarkably sharp and convincing opinions.

… [Richard Dawkins] is the scholar who has contributed most to the popularization of science in the past half-century.” _〈Christian Science Monitor〉

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: April 9, 2021

- Page count, weight, size: 656 pages | 938g | 150*220*40mm

- ISBN13: 9788934990260

- ISBN10: 8934990260

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)