Everything is in its place

|

Description

Book Introduction

- A word from MD

-

Oliver Sacks' unpublished essayThe final book containing Oliver Sacks' unpublished essays has been published.

Oliver Sacks, who maintained his love and positivity for the world until the end, even though he acknowledged that his time in this world was near.

He expressed the things he loved throughout his life and the values he pursued until the end in his own elegant sentences.

April 26, 2019. Essay PD Kim Tae-hee

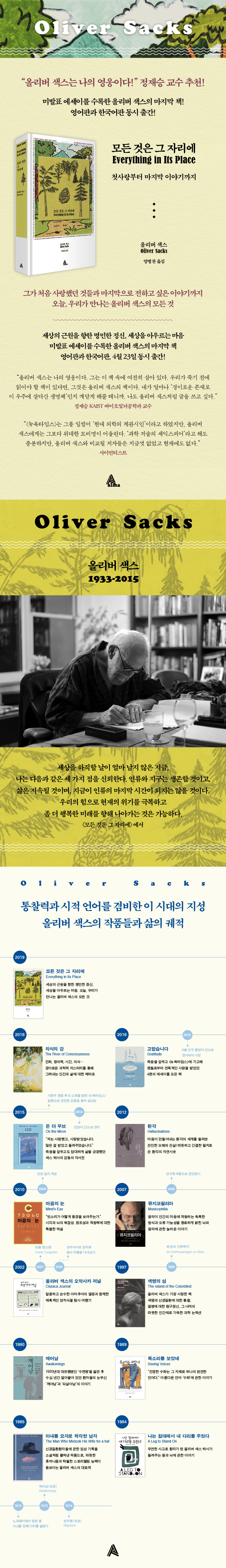

“Oliver Sacks is my hero!” Recommended by Professor Jeong Jae-seung!

From the things he first loved to the last story he wanted to tell

Today, we'll be covering everything Oliver Sacks has to offer.

Oliver Sacks's final book, featuring unpublished essays

Simultaneous publication of English and Korean editions

This collection of essays elegantly captures Oliver Sacks's pure passion, profound insight, and brilliant mind on "what makes us human." Through Everything in Its Place, we meet Oliver Sacks not only as a doctor, scientist, and writer, but also as a thoughtful friend and generous neighbor who remains with us today.

This book contains 33 essays that Oliver Sacks contributed to The New York Times, The New Yorker, Life, and other publications, or wrote in his notebooks, seven of which are being published for the first time.

"Everything in Its Place" will be published simultaneously in English and Korean on April 23, 2019.

The essays in "Everything in Its Place" are each a complete work imbued with sharp yet warm intellectual insight. Furthermore, each essay organically connects with the others, almost perfectly capturing the vast and beautiful figure that is Oliver Sacks.

In other words, it is a moving story that recreates the things he loved throughout his life and the values he pursued until his last moment, and it very successfully shows his side as a doctor who practices and preaches 'compassionate medicine' and as a scientist who manifests with boundless imagination and intellectual curiosity.

Moreover, as we read the sentences and narratives imbued with literary elegance, we find ourselves in awe of Oliver Sacks as a writer.

Therefore, this final collection of essays is virtually the only book available today that contains 'everything about Oliver Sacks'.

From the things he first loved to the last story he wanted to tell

Today, we'll be covering everything Oliver Sacks has to offer.

Oliver Sacks's final book, featuring unpublished essays

Simultaneous publication of English and Korean editions

This collection of essays elegantly captures Oliver Sacks's pure passion, profound insight, and brilliant mind on "what makes us human." Through Everything in Its Place, we meet Oliver Sacks not only as a doctor, scientist, and writer, but also as a thoughtful friend and generous neighbor who remains with us today.

This book contains 33 essays that Oliver Sacks contributed to The New York Times, The New Yorker, Life, and other publications, or wrote in his notebooks, seven of which are being published for the first time.

"Everything in Its Place" will be published simultaneously in English and Korean on April 23, 2019.

The essays in "Everything in Its Place" are each a complete work imbued with sharp yet warm intellectual insight. Furthermore, each essay organically connects with the others, almost perfectly capturing the vast and beautiful figure that is Oliver Sacks.

In other words, it is a moving story that recreates the things he loved throughout his life and the values he pursued until his last moment, and it very successfully shows his side as a doctor who practices and preaches 'compassionate medicine' and as a scientist who manifests with boundless imagination and intellectual curiosity.

Moreover, as we read the sentences and narratives imbued with literary elegance, we find ourselves in awe of Oliver Sacks as a writer.

Therefore, this final collection of essays is virtually the only book available today that contains 'everything about Oliver Sacks'.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

1.

first love

Water baby

Memories of South Kensington

first love

Humphry Davy, the poet of chemistry

library

A Journey into the Brain

2.

In the hospital room

Refrigerate

Neurological dreams

radish

God as seen from the third millennium

About hiccups

Traveling with Lowell

irresistible impulse

catastrophe

Dangerous Happiness

Tea and toast

virtual identity

Old brain and senescent brain

Kuru

Summer of Madness

Healing Community

3.

Life goes on

Is anyone there?

Herring Love

Rediscovering Colorado Springs

Botanists in the Park

In search of an island of stability

Reading fine print

Elephant's gait

orangutan

Why You Need a Garden

Night of the Ginkgo Tree

filter fish

Life goes on

References

source

Search

first love

Water baby

Memories of South Kensington

first love

Humphry Davy, the poet of chemistry

library

A Journey into the Brain

2.

In the hospital room

Refrigerate

Neurological dreams

radish

God as seen from the third millennium

About hiccups

Traveling with Lowell

irresistible impulse

catastrophe

Dangerous Happiness

Tea and toast

virtual identity

Old brain and senescent brain

Kuru

Summer of Madness

Healing Community

3.

Life goes on

Is anyone there?

Herring Love

Rediscovering Colorado Springs

Botanists in the Park

In search of an island of stability

Reading fine print

Elephant's gait

orangutan

Why You Need a Garden

Night of the Ginkgo Tree

filter fish

Life goes on

References

source

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

The 13th-century Scottish scholastic philosopher Duns Scotus praised 'condelectari sibi', meaning 'the will to find joy in one's own exercise'.

And Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, a psychologist of our time, emphasized ‘flow.’

As with everything involving flow, swimming has an inherent line, a rhythmic musical activity, so to speak.

And there is something wonderful about swimming: the wonder of floating in a thick, transparent medium that supports and envelops us.

Swimmers can move and play with water, but they cannot do similar activities in the air.

Swimmers can explore the dynamics and flow of water, waving their hands like propellers, steering like tiny rudders, or even becoming tiny hydrofoils or submarines to experience the physics of flow firsthand.

Going a step further, swimming holds immense symbolism, such as imaginative resonance and mythic potential.

My father called swimming the elixir of immortality, and he must have really believed it.

He enjoyed swimming every single day without fail, and as time passed, his pace slowed down little by little, until he lived to be ninety-four years old.

I wish I could follow in my father's footsteps and swim until I die.

--- From "Water Baby"

When I thought about the elements actually being on the periodic table, it really felt like they were the fundamental building blocks of the universe, and that the entire universe existed in microcosm in South Kensington.

When I looked at the periodic table, I was overwhelmed by the feeling that 'truth is beauty.'

That is, I felt that the periodic table was not something arbitrarily constructed by humans, but rather a true projection of the eternal order of the universe.

I also believed that whatever elements were added to the periodic table through future discoveries and advancements would only reinforce and reaffirm the truth of order. --- From "Memories of South Kensington"

Science is a human endeavor from start to finish, growing organically, evolutionarily, and humanly, with sudden bursts and pauses, and strange deviations.

We grow up shedding the stains of the past, but we never completely escape the past.

Just as we never completely escape childhood even as adults.

--- From "Humphry Davy, the Poet of Chemistry"

I generally hated school.

When I sat in a classroom and listened to a lecture, it felt like the information was going in one ear and out the other.

I hated being passive by nature, and I felt better when I was proactive in everything.

I had to learn on my own, what I wanted, in the way that worked best for me.

I was a good learner rather than a good student.

I wandered among the shelves and bookshelves of Wellesden Library (and every library I visited after that), choosing whatever books caught my eye, and that's how I became who I am.

I enjoyed my freedom in the library.

I was free to browse through thousands, even tens of thousands, of books, stroll around freely, and enjoy the special atmosphere and quiet companionship of other readers.

They all, like me, pursued only 'their own'.

--- From "Library"

We managed to obtain a chest X-ray taken in 1950 and a routine check-up X-ray, and discovered a small cancer cell that had been overlooked at the time.

The location of the lesion was identical to that of oat cell carcinoma.

Such aggressive malignant tumors grow rapidly and are usually fatal within a few months.

Yet, such an acute cancer remained intact for seven years! It seemed clear that, like other parts of the body, the cancer's activity and growth had been suppressed by refrigeration.

Now that my body temperature had returned to normal, the cancer seemed to be starting to rage as well.

Mr. Okins died a few days later after suffering from a severe cough.

His family saved his life by leaving him cold, and we ultimately drove him to death by giving him warmth.

--- From "Refrigerated Storage"

Neurological phenomena such as these are direct and vivid, and tend to intrude and disrupt dreams that would otherwise unfold normally.

However, it can be combined and fused with the dream, and transformed to fit the images and symbols of the dream itself.

Therefore, the flashes of light that precede a migraine can be fused with dreams and often appear as fireworks.

Similarly, one of my patients experienced a migraine aura creeping in and merging while dreaming of a nuclear bomb exploding.

At first, a dazzling fireball appeared, surrounded by a rainbow-colored zigzag border (a typical omen), which grew larger and brighter, until it was eventually replaced by a large dark spot, and the dream came to an end.

At this point, the patient usually woke up with the initial symptoms of fading blemishes, intense nausea, and headache.

--- From "Neurological Dreams"

Amidst the feelings of impulsivity and being cursed, people with Tourette syndrome can feel ostracized and pointed at for having a peculiar condition that no one around them shares or fully understands.

Many patients were ostracized or punished as children, and as adults were banned from public places such as restaurants.

For Lowell, who had experienced this firsthand for years, Lacrite was a veritable paradise.

As a person with Tourette Syndrome, it was the first place I lived without ever receiving a single harsh stare.

He fell in love with Larkrit so much that he dreamed of one day marrying a wonderful Mennonite woman with Tourette's syndrome and living happily ever after in Larkrit.

“I was tempted to live in New York,” he recalled after leaving Lacrite.

“But I also felt tempted to live with my family and friends in a place like Tourette Village.

But I was just a visitor, and no matter how much I was loved, I was still just a visitor.

“I could only belong to their world for a very short time.” --- From “Travels with Lowell”

Mr.

Q., with a single-minded devotion to faithfully carrying out his duties, checked every night to ensure that the windows and doors were safely closed, and also meticulously inspected the laundry room and boiler room to ensure they were functioning smoothly.

The nuns who ran the sanatorium, despite being fully aware of his confusion and delusions, tried to respect and even reinforce his identity.

The nuns believed that if his identity was destroyed, his life would be over.

So they encouraged him to carry out his duties faithfully, gave him the keys to several rooms, and told him to lock the doors thoroughly every night before going to bed.

The key ring he wore around his waist was a badge symbolizing his position and duties.

He looked around the kitchen, checking that the gas stove and the stove were switched off, and checking that there were no perishable foods left in the refrigerator.

Although his symptoms gradually worsened over the years, he was able to maintain a fairly organized and structured life thanks to the regular tasks he performed throughout the day (various checks, cleaning, and maintenance tasks).

Until the day he died of a sudden heart attack, he never doubted for a moment that he had served as a janitor at the school his entire life.

If you are a doctor or nursing home worker, Mr.

Would you tell a patient like Q, "You're no longer a janitor at school, but a declining dementia patient in a nursing home"? Would you strip him of his familiar virtual identity and replace it with a "reality" that's real to you but completely meaningless to him? That would be inappropriate, even cruel, and it's clear as day that it will hasten his decline.

--- From "Virtual Identity"

If we are lucky enough to reach a healthy old age, it will be the 'wonder of life' that keeps us passionate and productive until the very end.

--- From "The Old Brain and the Senile Brain"

The rest of the patients (the 99 percent of those with mental illness who cannot afford to pay out-of-pocket) face inadequate treatment and a life where their potential is not realized.

Millions of people with mental illness live among the least supported, most disenfranchised, and most excluded in our society today.

But given the various examples I've mentioned so far, two things are clear.

First, mental illness, including schizophrenia, is not an irreversible disease that constantly worsens.

(But it can be done.) Second, in an ideal environment, with sufficient resources, even the most severely mentally ill (those with a "hopeless" prognosis) can lead satisfying and productive lives.

--- From "Healing Community"

George Bernard Shaw called the book “Memories of a Race.”

Books should be published in as many formats as possible, and no type of book should disappear.

Because we are all unique individuals with highly individualized needs and preferences.

Preferences are built into every level of our brains, and our individual neural patterns and networks open up opportunities for a 'very personal connection' between author and reader.

--- From "Reading Grain-like Writing"

Nevertheless, I dare to hope that human life and cultural richness will survive, no matter what the odds, even if the Earth becomes desolate.

While some people view art as a cultural bulwark or a collective memory of humanity, I believe that science, with its profound thinking and tangible achievements and potential, is equally important.

These days, "good science" is flourishing like never before, with brilliant scientists leading the way, moving cautiously and slowly, their insights tested through constant self-examination and experimentation.

While I admire good writing, art, and music, I believe that only science, grounded in human virtues like decency, common sense, foresight, and concern for the unfortunate and the poor, can offer hope to a world mired in despair.

The potential of science can be realized not only through vast, centralized technologies, but also through the workers, farmers, and artisans of the entire planet.

(Pope Francis also emphasized this point in his encyclical.)

As I approach the end of this world, I trust in three things:

Humanity and the Earth will survive, life will continue, and this will not be the end of humanity.

It is possible for us to overcome the current crisis and move toward a happier future with our own strength.

And Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, a psychologist of our time, emphasized ‘flow.’

As with everything involving flow, swimming has an inherent line, a rhythmic musical activity, so to speak.

And there is something wonderful about swimming: the wonder of floating in a thick, transparent medium that supports and envelops us.

Swimmers can move and play with water, but they cannot do similar activities in the air.

Swimmers can explore the dynamics and flow of water, waving their hands like propellers, steering like tiny rudders, or even becoming tiny hydrofoils or submarines to experience the physics of flow firsthand.

Going a step further, swimming holds immense symbolism, such as imaginative resonance and mythic potential.

My father called swimming the elixir of immortality, and he must have really believed it.

He enjoyed swimming every single day without fail, and as time passed, his pace slowed down little by little, until he lived to be ninety-four years old.

I wish I could follow in my father's footsteps and swim until I die.

--- From "Water Baby"

When I thought about the elements actually being on the periodic table, it really felt like they were the fundamental building blocks of the universe, and that the entire universe existed in microcosm in South Kensington.

When I looked at the periodic table, I was overwhelmed by the feeling that 'truth is beauty.'

That is, I felt that the periodic table was not something arbitrarily constructed by humans, but rather a true projection of the eternal order of the universe.

I also believed that whatever elements were added to the periodic table through future discoveries and advancements would only reinforce and reaffirm the truth of order. --- From "Memories of South Kensington"

Science is a human endeavor from start to finish, growing organically, evolutionarily, and humanly, with sudden bursts and pauses, and strange deviations.

We grow up shedding the stains of the past, but we never completely escape the past.

Just as we never completely escape childhood even as adults.

--- From "Humphry Davy, the Poet of Chemistry"

I generally hated school.

When I sat in a classroom and listened to a lecture, it felt like the information was going in one ear and out the other.

I hated being passive by nature, and I felt better when I was proactive in everything.

I had to learn on my own, what I wanted, in the way that worked best for me.

I was a good learner rather than a good student.

I wandered among the shelves and bookshelves of Wellesden Library (and every library I visited after that), choosing whatever books caught my eye, and that's how I became who I am.

I enjoyed my freedom in the library.

I was free to browse through thousands, even tens of thousands, of books, stroll around freely, and enjoy the special atmosphere and quiet companionship of other readers.

They all, like me, pursued only 'their own'.

--- From "Library"

We managed to obtain a chest X-ray taken in 1950 and a routine check-up X-ray, and discovered a small cancer cell that had been overlooked at the time.

The location of the lesion was identical to that of oat cell carcinoma.

Such aggressive malignant tumors grow rapidly and are usually fatal within a few months.

Yet, such an acute cancer remained intact for seven years! It seemed clear that, like other parts of the body, the cancer's activity and growth had been suppressed by refrigeration.

Now that my body temperature had returned to normal, the cancer seemed to be starting to rage as well.

Mr. Okins died a few days later after suffering from a severe cough.

His family saved his life by leaving him cold, and we ultimately drove him to death by giving him warmth.

--- From "Refrigerated Storage"

Neurological phenomena such as these are direct and vivid, and tend to intrude and disrupt dreams that would otherwise unfold normally.

However, it can be combined and fused with the dream, and transformed to fit the images and symbols of the dream itself.

Therefore, the flashes of light that precede a migraine can be fused with dreams and often appear as fireworks.

Similarly, one of my patients experienced a migraine aura creeping in and merging while dreaming of a nuclear bomb exploding.

At first, a dazzling fireball appeared, surrounded by a rainbow-colored zigzag border (a typical omen), which grew larger and brighter, until it was eventually replaced by a large dark spot, and the dream came to an end.

At this point, the patient usually woke up with the initial symptoms of fading blemishes, intense nausea, and headache.

--- From "Neurological Dreams"

Amidst the feelings of impulsivity and being cursed, people with Tourette syndrome can feel ostracized and pointed at for having a peculiar condition that no one around them shares or fully understands.

Many patients were ostracized or punished as children, and as adults were banned from public places such as restaurants.

For Lowell, who had experienced this firsthand for years, Lacrite was a veritable paradise.

As a person with Tourette Syndrome, it was the first place I lived without ever receiving a single harsh stare.

He fell in love with Larkrit so much that he dreamed of one day marrying a wonderful Mennonite woman with Tourette's syndrome and living happily ever after in Larkrit.

“I was tempted to live in New York,” he recalled after leaving Lacrite.

“But I also felt tempted to live with my family and friends in a place like Tourette Village.

But I was just a visitor, and no matter how much I was loved, I was still just a visitor.

“I could only belong to their world for a very short time.” --- From “Travels with Lowell”

Mr.

Q., with a single-minded devotion to faithfully carrying out his duties, checked every night to ensure that the windows and doors were safely closed, and also meticulously inspected the laundry room and boiler room to ensure they were functioning smoothly.

The nuns who ran the sanatorium, despite being fully aware of his confusion and delusions, tried to respect and even reinforce his identity.

The nuns believed that if his identity was destroyed, his life would be over.

So they encouraged him to carry out his duties faithfully, gave him the keys to several rooms, and told him to lock the doors thoroughly every night before going to bed.

The key ring he wore around his waist was a badge symbolizing his position and duties.

He looked around the kitchen, checking that the gas stove and the stove were switched off, and checking that there were no perishable foods left in the refrigerator.

Although his symptoms gradually worsened over the years, he was able to maintain a fairly organized and structured life thanks to the regular tasks he performed throughout the day (various checks, cleaning, and maintenance tasks).

Until the day he died of a sudden heart attack, he never doubted for a moment that he had served as a janitor at the school his entire life.

If you are a doctor or nursing home worker, Mr.

Would you tell a patient like Q, "You're no longer a janitor at school, but a declining dementia patient in a nursing home"? Would you strip him of his familiar virtual identity and replace it with a "reality" that's real to you but completely meaningless to him? That would be inappropriate, even cruel, and it's clear as day that it will hasten his decline.

--- From "Virtual Identity"

If we are lucky enough to reach a healthy old age, it will be the 'wonder of life' that keeps us passionate and productive until the very end.

--- From "The Old Brain and the Senile Brain"

The rest of the patients (the 99 percent of those with mental illness who cannot afford to pay out-of-pocket) face inadequate treatment and a life where their potential is not realized.

Millions of people with mental illness live among the least supported, most disenfranchised, and most excluded in our society today.

But given the various examples I've mentioned so far, two things are clear.

First, mental illness, including schizophrenia, is not an irreversible disease that constantly worsens.

(But it can be done.) Second, in an ideal environment, with sufficient resources, even the most severely mentally ill (those with a "hopeless" prognosis) can lead satisfying and productive lives.

--- From "Healing Community"

George Bernard Shaw called the book “Memories of a Race.”

Books should be published in as many formats as possible, and no type of book should disappear.

Because we are all unique individuals with highly individualized needs and preferences.

Preferences are built into every level of our brains, and our individual neural patterns and networks open up opportunities for a 'very personal connection' between author and reader.

--- From "Reading Grain-like Writing"

Nevertheless, I dare to hope that human life and cultural richness will survive, no matter what the odds, even if the Earth becomes desolate.

While some people view art as a cultural bulwark or a collective memory of humanity, I believe that science, with its profound thinking and tangible achievements and potential, is equally important.

These days, "good science" is flourishing like never before, with brilliant scientists leading the way, moving cautiously and slowly, their insights tested through constant self-examination and experimentation.

While I admire good writing, art, and music, I believe that only science, grounded in human virtues like decency, common sense, foresight, and concern for the unfortunate and the poor, can offer hope to a world mired in despair.

The potential of science can be realized not only through vast, centralized technologies, but also through the workers, farmers, and artisans of the entire planet.

(Pope Francis also emphasized this point in his encyclical.)

As I approach the end of this world, I trust in three things:

Humanity and the Earth will survive, life will continue, and this will not be the end of humanity.

It is possible for us to overcome the current crisis and move toward a happier future with our own strength.

--- From "The World Goes On"

Publisher's Review

“Why on earth are humans born this way?”

This book is divided into three parts.

Part 1, 'First Love', tells the colorful stories of things Oliver Sacks has loved from his childhood to the present.

It begins with memories of swimming, which he loved so much from childhood until he became an adult, and continues with stories of museums called 'Books of Nature', the biology class he was engrossed in during his school days and the episodes that arose from it, a reminiscence of the libraries and books that helped him create his own world, and a short essay on Humphry Davy, who was called the 'poet of chemistry'.

Part 2, 'In the Sickroom', is full of essays that highlight his work as a doctor and scientist.

The book unfolds with colorful stories of clinical cases and research of patients encountered during his time as a medical student and as a neurologist.

Moreover, scientific considerations on the correlation between neurology and dreams, hallucinations, and near-death experiences, as well as philosophical reflections on temporary, continuous, and permanent nothingness and extinction, inevitably lead to fundamental questions about 'being human' itself.

Materials on hiccups, tics (Tourette's syndrome), depression, schizophrenia, old age, dementia, and Alzheimer's disease intertwine with interesting stories, leading to a warm appeal for a "healing community," not only for the relationship between illness and patients, but also for the new relationship we must form with patients.

A clear mind that turns to the origin of the world, a heart that embraces the world

A feast of beautiful sentences filled with Oliver Sacks's resolute hope.

Part 3, “Life Goes On,” contains essays that are deeply imbued with a yearning for the universe and affection for life forms in the natural world.

And that longing and affection also ignite into praise for one's own life.

Atul Gawande, the writer and physician, once said, “No one taught me better than Oliver Sacks how to be a doctor,” but readers of these final essays, even if they are not doctors, will recognize that “no one taught me better than Oliver Sacks how to live as a complete human being.”

As beings living on this beautiful planet called Earth, the wonders of life that we deserve.

At that very point, the book ends with a resolute sentence containing Oliver Sacks's final wish.

“Nevertheless, I dare to hope that human life and cultural richness will survive, no matter what the odds, even if the Earth becomes desolate.

…As I approach the end of this world, I trust in three things:

Humanity and the Earth will survive, life will continue, and this will not be the end of humanity.

“With our own strength, we can overcome the current crisis and move toward a happier future.”

_ [Life Goes On]

The final book by 'The Best Writer', including unpublished essays

The Scientist, in its forthcoming preview of Everything in Its Place, argues for a reevaluation of Oliver Sacks, asserting that “there has never been, and there is no author now, to compare with Sacks.”

“While his prolific writing career has long been deeply engraved in our culture, Sachs further solidifies his legend with this collection of essays.

The New York Times famously called Sacks "the poet laureate of modern medicine" in a 1990 review of "books with a clinical tone."

It may be presumptuous of me to say this, but I think Sax deserves a greater epitaph.

Although he could be called the "Shakespeare of science writing," I believe there has never been, and there are no authors today, who can compare to Sacks.

“I am glad that although cancer has taken his body, his voice still rings clearly in the ears of readers.”

_ Source: https://bit.ly/2GuZaaV, Translation: Yang Byeong-chan

This book includes seven previously unpublished essays: “On Hiccups,” “Travels with Lowell,” “Tea and Toast,” “Virtual Identity,” “The Orangutan,” “Why We Need Gardens,” and “Life Goes On.” (Some of “Travels with Lowell” has been published elsewhere.)

Especially in “Life Goes On,” which is located at the end of the book, Oliver Sacks ultimately fights the cancer that will take his life, and even while acknowledging that his days are numbered, he maintains his love, positivity, and hope for the world.

With elegant and dazzlingly beautiful sentences until the very end.

This book is divided into three parts.

Part 1, 'First Love', tells the colorful stories of things Oliver Sacks has loved from his childhood to the present.

It begins with memories of swimming, which he loved so much from childhood until he became an adult, and continues with stories of museums called 'Books of Nature', the biology class he was engrossed in during his school days and the episodes that arose from it, a reminiscence of the libraries and books that helped him create his own world, and a short essay on Humphry Davy, who was called the 'poet of chemistry'.

Part 2, 'In the Sickroom', is full of essays that highlight his work as a doctor and scientist.

The book unfolds with colorful stories of clinical cases and research of patients encountered during his time as a medical student and as a neurologist.

Moreover, scientific considerations on the correlation between neurology and dreams, hallucinations, and near-death experiences, as well as philosophical reflections on temporary, continuous, and permanent nothingness and extinction, inevitably lead to fundamental questions about 'being human' itself.

Materials on hiccups, tics (Tourette's syndrome), depression, schizophrenia, old age, dementia, and Alzheimer's disease intertwine with interesting stories, leading to a warm appeal for a "healing community," not only for the relationship between illness and patients, but also for the new relationship we must form with patients.

A clear mind that turns to the origin of the world, a heart that embraces the world

A feast of beautiful sentences filled with Oliver Sacks's resolute hope.

Part 3, “Life Goes On,” contains essays that are deeply imbued with a yearning for the universe and affection for life forms in the natural world.

And that longing and affection also ignite into praise for one's own life.

Atul Gawande, the writer and physician, once said, “No one taught me better than Oliver Sacks how to be a doctor,” but readers of these final essays, even if they are not doctors, will recognize that “no one taught me better than Oliver Sacks how to live as a complete human being.”

As beings living on this beautiful planet called Earth, the wonders of life that we deserve.

At that very point, the book ends with a resolute sentence containing Oliver Sacks's final wish.

“Nevertheless, I dare to hope that human life and cultural richness will survive, no matter what the odds, even if the Earth becomes desolate.

…As I approach the end of this world, I trust in three things:

Humanity and the Earth will survive, life will continue, and this will not be the end of humanity.

“With our own strength, we can overcome the current crisis and move toward a happier future.”

_ [Life Goes On]

The final book by 'The Best Writer', including unpublished essays

The Scientist, in its forthcoming preview of Everything in Its Place, argues for a reevaluation of Oliver Sacks, asserting that “there has never been, and there is no author now, to compare with Sacks.”

“While his prolific writing career has long been deeply engraved in our culture, Sachs further solidifies his legend with this collection of essays.

The New York Times famously called Sacks "the poet laureate of modern medicine" in a 1990 review of "books with a clinical tone."

It may be presumptuous of me to say this, but I think Sax deserves a greater epitaph.

Although he could be called the "Shakespeare of science writing," I believe there has never been, and there are no authors today, who can compare to Sacks.

“I am glad that although cancer has taken his body, his voice still rings clearly in the ears of readers.”

_ Source: https://bit.ly/2GuZaaV, Translation: Yang Byeong-chan

This book includes seven previously unpublished essays: “On Hiccups,” “Travels with Lowell,” “Tea and Toast,” “Virtual Identity,” “The Orangutan,” “Why We Need Gardens,” and “Life Goes On.” (Some of “Travels with Lowell” has been published elsewhere.)

Especially in “Life Goes On,” which is located at the end of the book, Oliver Sacks ultimately fights the cancer that will take his life, and even while acknowledging that his days are numbered, he maintains his love, positivity, and hope for the world.

With elegant and dazzlingly beautiful sentences until the very end.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of publication: April 23, 2019

- Page count, weight, size: 376 pages | 577g | 145*230*28mm

- ISBN13: 9791159922510

- ISBN10: 1159922519

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)