River of Consciousness

|

Description

Book Introduction

- A word from MD

-

Oliver Sacks' Last GiftA book in which Oliver Sacks shares his scientific knowledge along with his own experiences, while also introducing unfamiliar faces of great scientists such as botanist Darwin and neurologist Freud.

This book, filled with his love for humanity and passion for science, will keep him with us for a long time.

March 13, 2018. Natural Science PD Park Hyung-wook

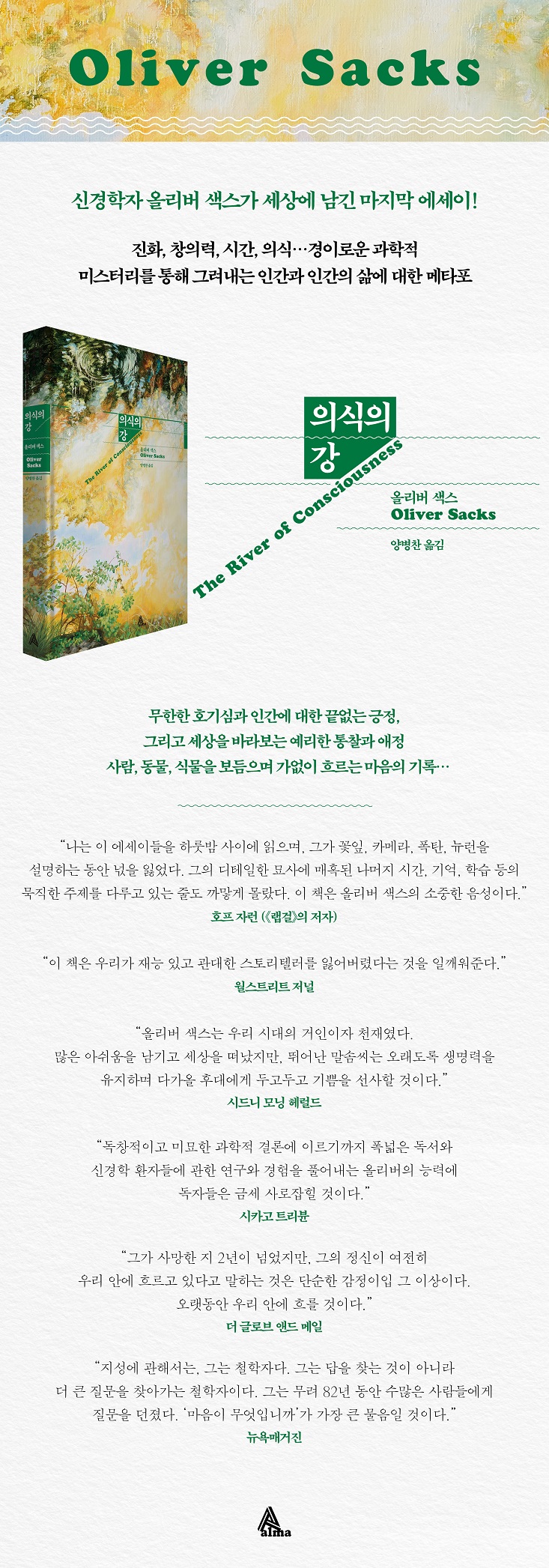

The final essay by neurologist Oliver Sacks

Evolution, creativity, time, consciousness… an endless passion for science,

And a moving metaphor for humanity!

Endless positivity toward humanity and keen insight into the world

A record of the endless flow of the heart, embracing people, animals, and plants…

"The River of Consciousness" is the final collection of essays by neuroscientist Oliver Sacks, which unravels the wondrous scientific mysteries of the people, animals, and plants living in this world and depicts them as metaphors for humanity and human life.

This book is a selection of manuscripts personally selected by Oliver Sacks just before he died of metastatic cancer in August 2015, and it became his final gift to his readers.

The ten essays included in "River of Consciousness" are manuscripts published in the New York Times and other publications during Oliver's lifetime.

In this book, with boundless curiosity and extensive knowledge, he unfolds scientific mysteries on topics such as evolution, creativity, time, and consciousness from lower animals to humans in an engaging way.

Some stories are autobiographical essays, while others are essays that unravel profound scientific research cases.

And he introduces in detail the writings and research value of the great scientists he always admired (Darwin, Freud, William James, etc.).

We introduce the lesser-known achievements and anecdotes of Charles Darwin, who presented the best evidence for the theory of evolution through his study of flowers; Freud, a neurologist who tirelessly studied the mysterious behavior of humans; and William James, who focused on the empirical specificity of time, memory, and creativity.

The American magazine [Science] said, “If I had to describe the feeling of reading the essays in this book in one word, it would be ‘like looking into a constantly flowing stream.’”

“As the water flows and lifts the pebbles, unexpected aspects appear underneath,” he commented.

Evolution, creativity, time, consciousness… an endless passion for science,

And a moving metaphor for humanity!

Endless positivity toward humanity and keen insight into the world

A record of the endless flow of the heart, embracing people, animals, and plants…

"The River of Consciousness" is the final collection of essays by neuroscientist Oliver Sacks, which unravels the wondrous scientific mysteries of the people, animals, and plants living in this world and depicts them as metaphors for humanity and human life.

This book is a selection of manuscripts personally selected by Oliver Sacks just before he died of metastatic cancer in August 2015, and it became his final gift to his readers.

The ten essays included in "River of Consciousness" are manuscripts published in the New York Times and other publications during Oliver's lifetime.

In this book, with boundless curiosity and extensive knowledge, he unfolds scientific mysteries on topics such as evolution, creativity, time, and consciousness from lower animals to humans in an engaging way.

Some stories are autobiographical essays, while others are essays that unravel profound scientific research cases.

And he introduces in detail the writings and research value of the great scientists he always admired (Darwin, Freud, William James, etc.).

We introduce the lesser-known achievements and anecdotes of Charles Darwin, who presented the best evidence for the theory of evolution through his study of flowers; Freud, a neurologist who tirelessly studied the mysterious behavior of humans; and William James, who focused on the empirical specificity of time, memory, and creativity.

The American magazine [Science] said, “If I had to describe the feeling of reading the essays in this book in one word, it would be ‘like looking into a constantly flowing stream.’”

“As the water flows and lifts the pebbles, unexpected aspects appear underneath,” he commented.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

introduction

What do flowers mean to Darwin?

Speed

The mental world of sentient plants and lower animals

The Freudian Young Neurologist We Didn't Know About

memory prone to errors

mishearing

Imitation and Creation

Maintaining homeostasis

River of Consciousness

Forgetting and ignoring are commonplace in cryptic science.

References

Search

What do flowers mean to Darwin?

Speed

The mental world of sentient plants and lower animals

The Freudian Young Neurologist We Didn't Know About

memory prone to errors

mishearing

Imitation and Creation

Maintaining homeostasis

River of Consciousness

Forgetting and ignoring are commonplace in cryptic science.

References

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

The concept of 'eternity' and the power of 'change, each small and undirected, but accumulating to create a new world (a world of incredible richness and variety)' were addictive.

Evolution has provided profound meaning and satisfaction to most people (something that belief in a divine plan has not).

The world that was once shrouded in a veil now has a transparent window through which we can look into the entire history of life.

The idea that evolution might have proceeded differently—that dinosaurs might still roam the Earth and humans might not have evolved yet—has puzzled me.

As a result, life felt more precious and like a wonderful ongoing adventure (Stephen Jay Gould called it a glorious accident).

Our lives are not fixed or predetermined, but are always susceptible to change and new experiences.

--- p.35~36

I am delighted that through Darwin I learned about my biological uniqueness, my biological history, and my biological kinship with other life forms.

This knowledge, taking root in my heart, makes nature feel like my home, and (apart from the role assigned to me in human civilization) gives me a sense of my own unique biological significance.

Animal life is far more complex than plant life, and human life is far more complex than that of any other animal, but all living things have their own biological significance.

And the origin of this biological meaning goes back to Darwin's insight into the meaning of flowers through his continuous study of plants.

I vaguely understood its meaning a long time ago in a garden in London.

--- p.37

We humans move at a relatively constant pace, but some people move a little faster and some move a little slower.

Even for one person, energy and engagement can vary depending on the time of day.

Also, when we are young, we are energetic, move a little quickly, and live briskly, but as we age, our movement speed and reaction time gradually slow down.

However, at least for ordinary people (in normal circumstances), these speeds are very limited.

There is no significant difference in reaction time between the elderly and the young, or between world-class athletes and recreational athletes.

The same is true for basic mental functions, such as computation, cognition, and visual association, where the top speeds do not differ significantly.

The dazzling performances of chess masters, the lightning-quick calculations of mental arithmetic masters, the performances of virtuosos, and the skills of other greats are due to their extensive knowledge, memorized patterns and strategies, and incredibly sophisticated techniques, not to their basic neural speed.

--- p.70

In The Voyage of the Beagle, Darwin described how an octopus in a tidal pool interacted with him, initially with wariness, later with curiosity, and even with playfulness.

Octopuses can be quite tame, and their keepers often develop a sense of empathy and a certain mental and emotional closeness to them.

There is much debate as to whether we can use the term consciousness for cephalopods.

However, no one would deny that dogs have a meaningful individual consciousness.

So why can't we acknowledge the octopus's equally powerful consciousness? --- p.88

There seems to be no mechanism in our minds or brains to verify the veracity of memories (or, at least, the existence of the characters appearing in them).

We have no direct access to historical truth, and our feelings and claims about truth depend equally on our senses and imagination.

Just like Helen Keller did.

There is no way to directly transmit or record events occurring in the world to the brain; they can only be filtered and reconstructed through highly subjective methods.

However, each person has a different method of filtering and reconstructing, and even when looking at one person, it is often refiltered and reinterpreted each time they recall it later.

So all we have is narrative truth, and the stories we tell others and ourselves are constantly being recategorized and refined.

This subjectivity is inherent in the very nature of memory, and this subjectivity originates from the foundations and mechanisms of the brain we possess.

It is truly remarkable that, despite this, major errors are relatively rare, and our memories are, for the most part, robust and reliable.

--- p.133~134

The impromptu invention of mishearing is sometimes imbued with a certain style or wit, which reflects to some extent the interests and experiences of the listener.

So rather than feeling embarrassed or uncomfortable about mishearing, I tend to enjoy it.

At least to my ears, 'cancer history' can be translated as 'Cantor's career' (Cantor is one of my favorite mathematicians), tarot cards as pteropods, grocery bags as poetry bags, all-or-noneness as oral numbness, porch as Porsche, and the simple phrase "Christmas Eve" can be translated as a request: "Kiss my feet!"

--- p.140~141

What is particularly noteworthy in Susan Sontag's account of her reading journey (she offered a similar account of primal creativity) is that "young souls, with their immense energy, enthusiasm, enthusiasm, and love, crave intellectual role models and tend to hone their craft by imitating them."

She had extensive knowledge of East and West, past and present, and the 'diversity of human nature and experience', and at some point, this knowledge became the driving force that led her to write her own work.

--- p.145~146

True originality requires not only conscious preparation and training, but also unconscious preparation, a process called the incubation period (or maturation period).

The incubation period is essential for integrating and digesting available resources and influences in the subconscious, reorganizing and synthesizing them into something of one's own.

--- p.155

Human consciousness gives thematic and personal continuity to the consciousness of every individual.

I'm sitting in a cafe on 7th Avenue writing this, watching the world go by.

My attention and focus flicker here and there, watching a girl in a red dress walk by, a man walk away with his funny-looking dog, and the sun finally breaking through the clouds.

But other than those things, there are also things that catch my attention unintentionally.

The sound of car horns, the smell of cigarette smoke, the glow of nearby streetlights… .

All these events caught my attention for a while.

But why, out of a thousand possible perceptions, do I focus solely on those? Perhaps it's due to reflection, memory, and association.

Consciousness is always active and selective, so it informs my choices and influences my perceptions.

So every emotion and meaning becomes uniquely mine.

Therefore, what I am looking at now is not just 7th Avenue, but 'my own 7th Avenue', which has my own individuality and identity added to it.

--- p.196~197

If you get caught up in the details, you can end up missing the forest for the trees.

Therefore, neuroscientists must not neglect the effort to reassemble the details and view them from the perspective of a coherent whole.

To do this, it is necessary to understand determinants at all levels, from the neurophysiological level to the psychological level and even the sociological level.

We must also consider the ongoing and interesting interactions between various determinants.

--- p.208

For us to embrace a new idea, it is not enough to grasp or understand something instantly; our minds must be able to receive and retain it.

To do that, we must first allow ourselves to encounter new ideas.

That is, we must create mental spaces and categories (with potential relevance to new ideas) and then bring new ideas into full and stable consciousness.

Then you have to give them conceptual form and hold them in your mind.

Even if it conflicts with one's existing concepts, beliefs, and categories.

This process of accommodation and securing mental space determines whether an idea or discovery will capture the public's attention and bear fruit, or whether it will fade and be forgotten, never bearing fruit and disappearing.

Evolution has provided profound meaning and satisfaction to most people (something that belief in a divine plan has not).

The world that was once shrouded in a veil now has a transparent window through which we can look into the entire history of life.

The idea that evolution might have proceeded differently—that dinosaurs might still roam the Earth and humans might not have evolved yet—has puzzled me.

As a result, life felt more precious and like a wonderful ongoing adventure (Stephen Jay Gould called it a glorious accident).

Our lives are not fixed or predetermined, but are always susceptible to change and new experiences.

--- p.35~36

I am delighted that through Darwin I learned about my biological uniqueness, my biological history, and my biological kinship with other life forms.

This knowledge, taking root in my heart, makes nature feel like my home, and (apart from the role assigned to me in human civilization) gives me a sense of my own unique biological significance.

Animal life is far more complex than plant life, and human life is far more complex than that of any other animal, but all living things have their own biological significance.

And the origin of this biological meaning goes back to Darwin's insight into the meaning of flowers through his continuous study of plants.

I vaguely understood its meaning a long time ago in a garden in London.

--- p.37

We humans move at a relatively constant pace, but some people move a little faster and some move a little slower.

Even for one person, energy and engagement can vary depending on the time of day.

Also, when we are young, we are energetic, move a little quickly, and live briskly, but as we age, our movement speed and reaction time gradually slow down.

However, at least for ordinary people (in normal circumstances), these speeds are very limited.

There is no significant difference in reaction time between the elderly and the young, or between world-class athletes and recreational athletes.

The same is true for basic mental functions, such as computation, cognition, and visual association, where the top speeds do not differ significantly.

The dazzling performances of chess masters, the lightning-quick calculations of mental arithmetic masters, the performances of virtuosos, and the skills of other greats are due to their extensive knowledge, memorized patterns and strategies, and incredibly sophisticated techniques, not to their basic neural speed.

--- p.70

In The Voyage of the Beagle, Darwin described how an octopus in a tidal pool interacted with him, initially with wariness, later with curiosity, and even with playfulness.

Octopuses can be quite tame, and their keepers often develop a sense of empathy and a certain mental and emotional closeness to them.

There is much debate as to whether we can use the term consciousness for cephalopods.

However, no one would deny that dogs have a meaningful individual consciousness.

So why can't we acknowledge the octopus's equally powerful consciousness? --- p.88

There seems to be no mechanism in our minds or brains to verify the veracity of memories (or, at least, the existence of the characters appearing in them).

We have no direct access to historical truth, and our feelings and claims about truth depend equally on our senses and imagination.

Just like Helen Keller did.

There is no way to directly transmit or record events occurring in the world to the brain; they can only be filtered and reconstructed through highly subjective methods.

However, each person has a different method of filtering and reconstructing, and even when looking at one person, it is often refiltered and reinterpreted each time they recall it later.

So all we have is narrative truth, and the stories we tell others and ourselves are constantly being recategorized and refined.

This subjectivity is inherent in the very nature of memory, and this subjectivity originates from the foundations and mechanisms of the brain we possess.

It is truly remarkable that, despite this, major errors are relatively rare, and our memories are, for the most part, robust and reliable.

--- p.133~134

The impromptu invention of mishearing is sometimes imbued with a certain style or wit, which reflects to some extent the interests and experiences of the listener.

So rather than feeling embarrassed or uncomfortable about mishearing, I tend to enjoy it.

At least to my ears, 'cancer history' can be translated as 'Cantor's career' (Cantor is one of my favorite mathematicians), tarot cards as pteropods, grocery bags as poetry bags, all-or-noneness as oral numbness, porch as Porsche, and the simple phrase "Christmas Eve" can be translated as a request: "Kiss my feet!"

--- p.140~141

What is particularly noteworthy in Susan Sontag's account of her reading journey (she offered a similar account of primal creativity) is that "young souls, with their immense energy, enthusiasm, enthusiasm, and love, crave intellectual role models and tend to hone their craft by imitating them."

She had extensive knowledge of East and West, past and present, and the 'diversity of human nature and experience', and at some point, this knowledge became the driving force that led her to write her own work.

--- p.145~146

True originality requires not only conscious preparation and training, but also unconscious preparation, a process called the incubation period (or maturation period).

The incubation period is essential for integrating and digesting available resources and influences in the subconscious, reorganizing and synthesizing them into something of one's own.

--- p.155

Human consciousness gives thematic and personal continuity to the consciousness of every individual.

I'm sitting in a cafe on 7th Avenue writing this, watching the world go by.

My attention and focus flicker here and there, watching a girl in a red dress walk by, a man walk away with his funny-looking dog, and the sun finally breaking through the clouds.

But other than those things, there are also things that catch my attention unintentionally.

The sound of car horns, the smell of cigarette smoke, the glow of nearby streetlights… .

All these events caught my attention for a while.

But why, out of a thousand possible perceptions, do I focus solely on those? Perhaps it's due to reflection, memory, and association.

Consciousness is always active and selective, so it informs my choices and influences my perceptions.

So every emotion and meaning becomes uniquely mine.

Therefore, what I am looking at now is not just 7th Avenue, but 'my own 7th Avenue', which has my own individuality and identity added to it.

--- p.196~197

If you get caught up in the details, you can end up missing the forest for the trees.

Therefore, neuroscientists must not neglect the effort to reassemble the details and view them from the perspective of a coherent whole.

To do this, it is necessary to understand determinants at all levels, from the neurophysiological level to the psychological level and even the sociological level.

We must also consider the ongoing and interesting interactions between various determinants.

--- p.208

For us to embrace a new idea, it is not enough to grasp or understand something instantly; our minds must be able to receive and retain it.

To do that, we must first allow ourselves to encounter new ideas.

That is, we must create mental spaces and categories (with potential relevance to new ideas) and then bring new ideas into full and stable consciousness.

Then you have to give them conceptual form and hold them in your mind.

Even if it conflicts with one's existing concepts, beliefs, and categories.

This process of accommodation and securing mental space determines whether an idea or discovery will capture the public's attention and bear fruit, or whether it will fade and be forgotten, never bearing fruit and disappearing.

--- p.220~221

Publisher's Review

Insight into the world and literary writing

This book includes Charles Darwin's 'Origin of Species' and William James' 'Principles of Psychology', which are considered masterpieces in the history of science, as well as H.

A variety of scientific books and research, ranging from the novels of G. Wells, to anecdotes of scientists who overcame the obstacles of their time, are introduced.

This is a captivating human story told through Oliver Sacks's masterful writing, and it also captivates readers with the mysteries of nature and brilliant inspiration that he uncovers one by one through his vast scientific knowledge and curiosity.

Along with the deep and wide scientific issues, Oliver Sacks' autobiographical episodes are as fascinating as a fascinating piece of fiction.

An episode where I gained a vague understanding of evolution and the biological meaning of all living things through my mother's story about the magnolia tree, which awakened my sense of a world "without bees and butterflies, and without the fragrance and color of flowers" as a child; an episode where I mistook "a publicist with Lou Gehrig's disease" for "a cuttlefish with Lou Gehrig's disease" and believed that cephalopods (octopuses, cuttlefish, etc.) with sophisticated nervous systems could easily do the same.

Among them, the story of the thermite bomb that fell in the backyard of my childhood home is the best, and that terrifying memory was because I mistook reading the contents of my brother's letter for a memory I had experienced myself.

He explains:

“We humans are fallible, have weak and imperfect memories, but we are nevertheless endowed with remarkable flexibility and creativity.” In this way, Oliver Sacks does more than just convey little-known scientific information through this book.

He examines the evolutionary process of various plants and animals, and shares with readers the realization that “humans today may be the result of a dazzlingly beautiful coincidence, and that their lives may also be an even more precious and wondrous ongoing process.”

And in cases of 'mishearing' caused by errors in brain regions, he says that human perception reflects each person's interests and experiences, and that he hears 'grocery bag' as 'poetry bag', 'porch' as 'Porsche', and the simple comment 'Christmas Eve' as a request 'Kiss my feet!'

This is Oliver Sacks' insight, and the power of literary writing.

Therefore, 『The River of Consciousness』 can be said to be a book that contains Oliver Sacks' boundless scientific curiosity to explore unknown realms, as well as a touching metaphor that looks at humans and human life with affection and positivity.

Fascinating Questions About the Human Brain and Mental Activity

'Do lower animals like earthworms have a mental world like humans?'

'How do the speed and time perceptions of humans differ from those of other plants and animals?'

'Is human memory reliable?'

How is human creativity expressed?

As with other books by neurologist Oliver Sacks, this book delves into the unknown questions about the human brain and mental activity.

He embarks on a scientific journey to answer these questions, recalling famous books, papers, letters, and clinical records of patients he personally treated.

Thus, Dr. Sacks shares with his readers scientific findings such as the fact that cephalopods can express complex emotions and intentions by changing the color, pattern, and texture of their skin; that people with Tourette's and Parkinson's syndrome have a sense of time and speed that far surpasses that of the average person; that human memory is constantly recategorized and refined, so that it can only be a narrative truth; and that imitation is essential to the expression of creativity and that there is a period of unconscious maturation.

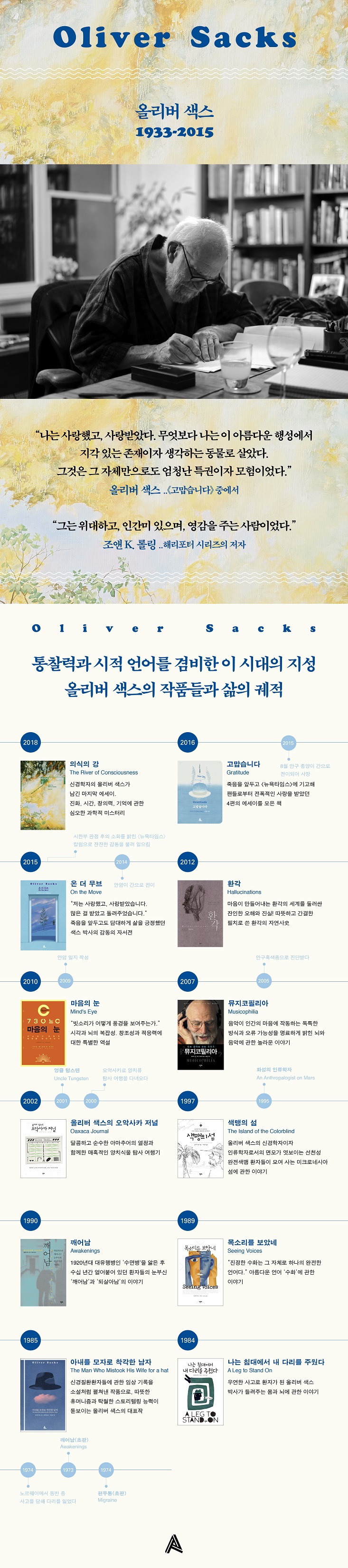

He was the most influential neuroscientist of our time.

He was a remarkable writer who continued his research to understand the human mind and behavior, and told fascinating and moving stories about it until the end of his life.

He was a "warm scholar" who tried to communicate with the public the story of the human brain and mind, the most difficult field to explain, and also tried to explain the most scientific and logical topics into humane and literary stories.

[New York Magazine] said this:

“As for intelligence, he is a philosopher.

He is a philosopher who does not seek answers, but seeks bigger questions.

He asked questions to countless people for a whopping 82 years.

The biggest question would be, 'What is the mind?'

boundless love for humanity and science

“Above all, I lived on this beautiful planet as a sentient being, a thinking animal.

“That in itself was an incredible privilege and adventure.” His writings in his later years, such as “Thank You,” written shortly before his death at age 82, shine with insight and beauty.

Until the end of his life, he praised and explored the beauty of people, animals, and plants living in this world and its pure, unknown realm.

His writings were always filled with boundless curiosity about science and love for humanity, leading the New York Times to call him “the poet laureate of medicine.”

Bill Hayes, the writer who was also Oliver Sacks's last lover, recalled the day the book was first put together:

“In August 2015, he could have died soon.

I remember that day very vividly.

Oliver suddenly regained his energy.

I sat down at my desk and recited the table of contents for what would become my last book.

Perhaps it was a welcome distraction from the 'terrible boredom' of 'dying'.

“For Oliver, boredom was worse than the discomfort he had endured.” Oliver Sacks has constantly communicated with us, through his insightful poetic language, to enable us to look more closely at the history of life and human life through the transparent window of science.

This book, the last one he left behind, makes us reflect on the message he left us.

“A beautiful life is one that continually pursues something.”

This book includes Charles Darwin's 'Origin of Species' and William James' 'Principles of Psychology', which are considered masterpieces in the history of science, as well as H.

A variety of scientific books and research, ranging from the novels of G. Wells, to anecdotes of scientists who overcame the obstacles of their time, are introduced.

This is a captivating human story told through Oliver Sacks's masterful writing, and it also captivates readers with the mysteries of nature and brilliant inspiration that he uncovers one by one through his vast scientific knowledge and curiosity.

Along with the deep and wide scientific issues, Oliver Sacks' autobiographical episodes are as fascinating as a fascinating piece of fiction.

An episode where I gained a vague understanding of evolution and the biological meaning of all living things through my mother's story about the magnolia tree, which awakened my sense of a world "without bees and butterflies, and without the fragrance and color of flowers" as a child; an episode where I mistook "a publicist with Lou Gehrig's disease" for "a cuttlefish with Lou Gehrig's disease" and believed that cephalopods (octopuses, cuttlefish, etc.) with sophisticated nervous systems could easily do the same.

Among them, the story of the thermite bomb that fell in the backyard of my childhood home is the best, and that terrifying memory was because I mistook reading the contents of my brother's letter for a memory I had experienced myself.

He explains:

“We humans are fallible, have weak and imperfect memories, but we are nevertheless endowed with remarkable flexibility and creativity.” In this way, Oliver Sacks does more than just convey little-known scientific information through this book.

He examines the evolutionary process of various plants and animals, and shares with readers the realization that “humans today may be the result of a dazzlingly beautiful coincidence, and that their lives may also be an even more precious and wondrous ongoing process.”

And in cases of 'mishearing' caused by errors in brain regions, he says that human perception reflects each person's interests and experiences, and that he hears 'grocery bag' as 'poetry bag', 'porch' as 'Porsche', and the simple comment 'Christmas Eve' as a request 'Kiss my feet!'

This is Oliver Sacks' insight, and the power of literary writing.

Therefore, 『The River of Consciousness』 can be said to be a book that contains Oliver Sacks' boundless scientific curiosity to explore unknown realms, as well as a touching metaphor that looks at humans and human life with affection and positivity.

Fascinating Questions About the Human Brain and Mental Activity

'Do lower animals like earthworms have a mental world like humans?'

'How do the speed and time perceptions of humans differ from those of other plants and animals?'

'Is human memory reliable?'

How is human creativity expressed?

As with other books by neurologist Oliver Sacks, this book delves into the unknown questions about the human brain and mental activity.

He embarks on a scientific journey to answer these questions, recalling famous books, papers, letters, and clinical records of patients he personally treated.

Thus, Dr. Sacks shares with his readers scientific findings such as the fact that cephalopods can express complex emotions and intentions by changing the color, pattern, and texture of their skin; that people with Tourette's and Parkinson's syndrome have a sense of time and speed that far surpasses that of the average person; that human memory is constantly recategorized and refined, so that it can only be a narrative truth; and that imitation is essential to the expression of creativity and that there is a period of unconscious maturation.

He was the most influential neuroscientist of our time.

He was a remarkable writer who continued his research to understand the human mind and behavior, and told fascinating and moving stories about it until the end of his life.

He was a "warm scholar" who tried to communicate with the public the story of the human brain and mind, the most difficult field to explain, and also tried to explain the most scientific and logical topics into humane and literary stories.

[New York Magazine] said this:

“As for intelligence, he is a philosopher.

He is a philosopher who does not seek answers, but seeks bigger questions.

He asked questions to countless people for a whopping 82 years.

The biggest question would be, 'What is the mind?'

boundless love for humanity and science

“Above all, I lived on this beautiful planet as a sentient being, a thinking animal.

“That in itself was an incredible privilege and adventure.” His writings in his later years, such as “Thank You,” written shortly before his death at age 82, shine with insight and beauty.

Until the end of his life, he praised and explored the beauty of people, animals, and plants living in this world and its pure, unknown realm.

His writings were always filled with boundless curiosity about science and love for humanity, leading the New York Times to call him “the poet laureate of medicine.”

Bill Hayes, the writer who was also Oliver Sacks's last lover, recalled the day the book was first put together:

“In August 2015, he could have died soon.

I remember that day very vividly.

Oliver suddenly regained his energy.

I sat down at my desk and recited the table of contents for what would become my last book.

Perhaps it was a welcome distraction from the 'terrible boredom' of 'dying'.

“For Oliver, boredom was worse than the discomfort he had endured.” Oliver Sacks has constantly communicated with us, through his insightful poetic language, to enable us to look more closely at the history of life and human life through the transparent window of science.

This book, the last one he left behind, makes us reflect on the message he left us.

“A beautiful life is one that continually pursues something.”

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: March 6, 2018

- Page count, weight, size: 252 pages | 412g | 146*232*20mm

- ISBN13: 9791159921384

- ISBN10: 1159921385

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)