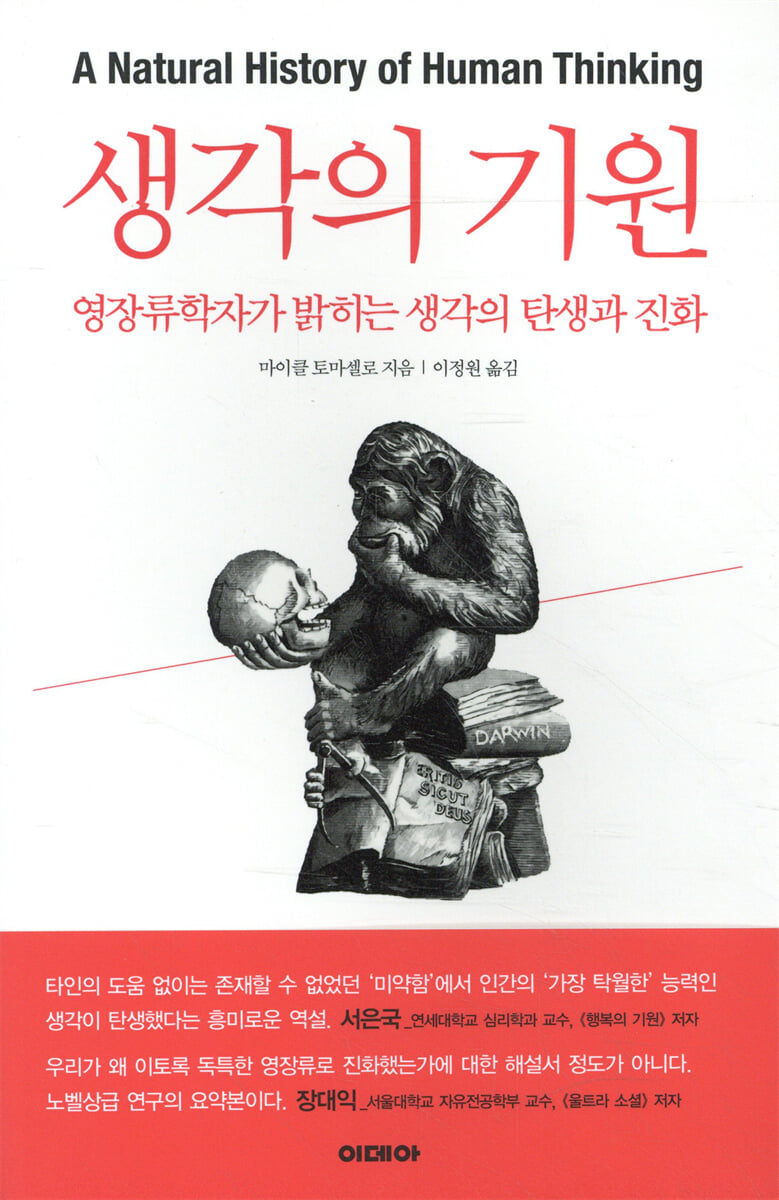

The origin of thought

|

Description

Book Introduction

Searching for the Origins of Thought in a Fossil-Free World

A primatologist's scientific and evolutionary interpretation of our conceptual and abstract understanding of thought.

From the "weakness" of desperate need for help from others, the "excellent ability" of human thinking was born and evolved.

"How did Sapiens, alone among apes, achieve civilization? If there's one scientist who can answer this profound question, it's undoubtedly Michael Tomasello.

Because no one on Earth has looked as deeply into the subtle gap between humans and other ape species as Tomasello.

This isn't just an explanatory book about why we evolved into such unique primates.

“This is a summary of Nobel Prize-worthy research.” (Professor Daeik Jang, College of Liberal Arts, Seoul National University)

“High-level thinking ability is central to the identity of Homo sapiens.

The world's leading scholars offer an explanation of the big question of how and why this ability arose, with unparalleled depth and clarity.

“It conveys the intriguing paradox that the most extraordinary human ability (thinking!) was actually born from a weakness that made it impossible to exist alone without the help of others.” (Seo Eun-guk, Professor of Psychology, Yonsei University)

The two quotes above are recommendations for the book “The Origin of Thought” from leading Korean evolutionary scholars and psychologists, and they ask the same question.

The question is, “Why did only humans (humanity) evolve with unique abilities (thinking!) and achieve civilization?”

That is why, among the countless apes that have branched out in various branches of evolution, only Sapiens were the exception.

A primatologist's scientific and evolutionary interpretation of our conceptual and abstract understanding of thought.

From the "weakness" of desperate need for help from others, the "excellent ability" of human thinking was born and evolved.

"How did Sapiens, alone among apes, achieve civilization? If there's one scientist who can answer this profound question, it's undoubtedly Michael Tomasello.

Because no one on Earth has looked as deeply into the subtle gap between humans and other ape species as Tomasello.

This isn't just an explanatory book about why we evolved into such unique primates.

“This is a summary of Nobel Prize-worthy research.” (Professor Daeik Jang, College of Liberal Arts, Seoul National University)

“High-level thinking ability is central to the identity of Homo sapiens.

The world's leading scholars offer an explanation of the big question of how and why this ability arose, with unparalleled depth and clarity.

“It conveys the intriguing paradox that the most extraordinary human ability (thinking!) was actually born from a weakness that made it impossible to exist alone without the help of others.” (Seo Eun-guk, Professor of Psychology, Yonsei University)

The two quotes above are recommendations for the book “The Origin of Thought” from leading Korean evolutionary scholars and psychologists, and they ask the same question.

The question is, “Why did only humans (humanity) evolve with unique abilities (thinking!) and achieve civilization?”

That is why, among the countless apes that have branched out in various branches of evolution, only Sapiens were the exception.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Introduction: What Makes Human Thought Unique? 4

Chapter 1: The Shared Orientation Hypothesis. p11

Privileges given to cooperative animals

Chapter 2: Personal Orientation. p21

Apes think too

The Evolution of Cognition.p24

Apes think. p34

Cognitive Abilities for Competition.p50

Chapter 3: Co-Directionality. p59

Why Human Thinking Differs from Chimpanzee Thinking

A new type of cooperation. p63

A new type of collaborative communication. p85

Thinking between two people. p113

Point of view: The ability to shift one's perspective. p123

Chapter 4: Group Orientation. p129

The birth of an idea that is not from anyone's perspective

The Emergence of Culture. p133

The Emergence of Conventional Communication. p148

Subject-neutral thinking. p177

Objectivity: A perspective without a specific point of view. p186

Chapter 5: Human Thought Originated in Cooperation. p191

The sociality inherent in thought, a uniquely human trait

Evolutionary theories of human cognition. p195

Sociality and Thought. p206

Role in ontogeny. p220

Conclusion: Finding the Origins of Thought in a Fossil-Free World. p227

Translator's Note. p237

References.p242

Look it up.p259

Chapter 1: The Shared Orientation Hypothesis. p11

Privileges given to cooperative animals

Chapter 2: Personal Orientation. p21

Apes think too

The Evolution of Cognition.p24

Apes think. p34

Cognitive Abilities for Competition.p50

Chapter 3: Co-Directionality. p59

Why Human Thinking Differs from Chimpanzee Thinking

A new type of cooperation. p63

A new type of collaborative communication. p85

Thinking between two people. p113

Point of view: The ability to shift one's perspective. p123

Chapter 4: Group Orientation. p129

The birth of an idea that is not from anyone's perspective

The Emergence of Culture. p133

The Emergence of Conventional Communication. p148

Subject-neutral thinking. p177

Objectivity: A perspective without a specific point of view. p186

Chapter 5: Human Thought Originated in Cooperation. p191

The sociality inherent in thought, a uniquely human trait

Evolutionary theories of human cognition. p195

Sociality and Thought. p206

Role in ontogeny. p220

Conclusion: Finding the Origins of Thought in a Fossil-Free World. p227

Translator's Note. p237

References.p242

Look it up.p259

Publisher's Review

The 'Scientific (Evolutionary) Origins' of Human Thought

This book is a scientific (evolutionary) answer to the question, “Why did human thought arise and how did it evolve?” by world-renowned primatologist Michael Tomasello.

This book deals with the 'scientific (evolutionary) origins' of human thought, which has been perceived as an abstract and conceptual realm.

Professor Jang Dae-ik previously described the author of this book, Tomasello, as “no one on Earth has ever looked so deeply into the subtle gap between humans and other ape species,” and this is no exaggeration.

Tomasello has studied cognition, language acquisition, and cultural formation in primates and humans for over 30 years.

He is currently the director of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, and is also a dedicated and excellent researcher himself.

Tomasello's books and papers have been cited an average of 9,500 times per year over the past five years, and his continued publication of papers annually as first or sole author is a testament to his prominence.

There is an indicator called 'h-index' to refer to the academic contribution of a researcher.

If the h-index is 100, it means that there are more than 100 books or papers that have been cited more than 100 times.

You cannot raise your h-index with papers that are trendy or papers that are only for a living.

To increase your h-index, you must consistently publish papers that are widely cited by your fellow researchers.

According to 'Google Scholar', there are about 2,500 researchers with an h-index of 100 or higher, regardless of field, and only 210 with a score of 150 or higher.

Tomasello's h-index is 159, which is similar to that of Karl Marx (163), who presented one of the most controversial and important issues in human history.

Apes think too, just 'thinking about themselves'

In this book, world-renowned primatologist Tomasello traces the evolutionary history of thought back to before humans diverged from other apes.

Humans share a common ancestor with great apes such as chimpanzees and bonobos.

Humans appear to have split from other apes around 6 million years ago, and Tomasello hypothesizes that humans at this time were no different from apes.

For example, when chimpanzees hunt monkeys, they chase them together in groups.

But it's hard to see the chimpanzees cooperating.

This is because monkeys tend to hunt together and monopolize the food rather than share it with each other.

In this situation, chimpanzee social cognition is competitive rather than cooperative.

Like chimpanzees today, for over 5 million years, human thought was individualistic, operating on social cognition that was both competitive (getting more food) and exploitative (getting as much as possible).

Tomasello explains this with the concept of 'individual intentionality'.

“Imagine a common ancestor between humans and great apes.

Their daily lives were similar to those of present-day apes.

They spent most of their waking hours in small groups, engaged in a variety of social interactions, were largely competitive, and had to forage for food individually.

“My hypothesis is that the common ancestor of apes and humans (and perhaps including Australopithecus, which occupies the first 4 million years of human evolutionary history) was self-oriented and instrumental rational.” (p. 56)

“Individual orientation is primarily necessary for species that engage in competitive social interactions.

They act for themselves, or at best, cooperate temporarily to gain an advantage in a fight.

The social cognitive abilities of great apes evolved primarily to compete with other individuals in groups.

Apes believe in a kind of Machiavellian intelligence.

They viewed group members as future competitors and sought to win the competition.

Recent research suggests that the most complex social cognitive abilities of great apes are driven by competition and exploitation, rather than by cooperation or communication.

“The cognitive abilities of great apes are entirely geared towards competition.” (p. 57)

Why Humans Think Differently From Chimpanzees: Pick a Bad Partner and You'll Starve

It was not until about 400,000 years ago that human thinking began to diverge from that of chimpanzees, from a self-centered, individualistic state.

Tomasello speculates that Homo heidelbergensis was probably the first human to acquire new cognitive skills, and classifies this period as the 'early human' stage.

Early humans set common goals and lived cooperatively in small groups, requiring them to utilize social cognitive functions different from those previously available.

Early humans needed social intelligence to understand the intentions of others, and they began to reflect (think!) on their own communication and actions from the perspective of others.

That is, it was only after almost 5 million years that we began to think of ourselves from the perspective of ‘you’ for the sake of our ‘common (our)’ goal (hunting).

Tomasello distinguishes this from the previous stage, 'individual intentionality', with the concept of 'joint intentionality'.

“Homo heidelbergensis was the common ancestor of Neanderthals and modern humans, and is a hominin that remains enigmatic.

Paleoanthropological evidence suggests that Homo heidelbergensis was the first hominin to systematically cooperate to hunt large animals.

They used weapons that required cooperation, and sometimes brought game home.

This was also a time when brain capacity and population size rapidly increased.

Homo heidelbergensis was a true candidate for cooperation… … Since humans could no longer obtain food on their own, cooperation was necessary.

If we didn't develop new technologies and motivations for cooperation, we would starve to death.

There was a direct and immediate selection pressure on the motivation and skills for cooperative activities (joint orientation).

Second, we began to evaluate others as collaborative partners.

This is a social choice.

If you choose a bad partner, you will starve.

Swindlers and lazy people are avoided, and even scoundrels are avoided.

Early humans faced concerns that other apes did not.

“I began to worry about how I should evaluate others and how others would evaluate me.” (pp. 68-69)

“At some point, early humans began to understand their interdependence with others not only in the context of cooperative activities but also in broader terms, such as the idea that helping a partner not to starve tonight is necessary to ensure that the partner is in good condition for tomorrow’s hunt.” (p. 87)

The Birth of Something Beyond 'Me' and 'You'

About 200,000 years ago, as Homo sapiens entered the era, the scale of cooperation expanded from small 'herds' to 'groups'.

Modern humans have gone a step further than early humans by creating virtual entities called social institutions and endowing them with power.

This means that 'I (the individual)' began to evaluate myself from the group's perspective in order to reveal that I am a being who can perform cooperative activities well as a member of the community.

And moving beyond thinking of you from my perspective, or me from your perspective, we began to think of me and you from the perspective of the group, and of a third party (member).

This explains that humanity has evolved into a different stage from the previous stage (the stage of communal intentionality), and has entered the stage of 'collective intentionality'.

This sociality of 'sharing the group's orientation' that goes beyond me and you has led to a groundbreaking change (evolution) in the thinking of modern humans.

“The small-scale, impromptu cooperation of early humans whenever they needed food was a stable evolutionary strategy.

However, my hypothesis is that over time, two demographic problems arose, necessitating a change in strategy. The first problem was intergroup competition.

To protect their lives from invaders, they had to form proper social groups rather than loose cooperative organizations.

A cooperative group with a common goal of survival (securing food and defending against invasion) and a division of labor system was needed.

This means that group members were motivated to help each other.

Because group members were interdependent, they had an incentive to help each other.

'We' had to join forces to prepare for 'their' invasion.

So individuals began to understand their identity as members of a particular social group that shared a culture.

“A cultural foundation was established based on the orientation of ‘we’ that encompasses the entire group.” (p. 134)

“The second problem was population growth.

As the population grew, several tribes became grouped into a single supergroup, and tribes emerged that shared a single 'culture'.

This means that the problem of how members of a cultural group identify each other has become important.

I had to be able to recognize the other person, but the other person had to be able to recognize me too.

Because only members of a group could share values and cooperate.

In modern human society, group identity is expressed in various ways, but in the beginning it was probably expressed only through behavior.

“People who spoke, cooked, and fished in the same way—that is, people who shared cultural practices—were more likely to belong to the same cultural group.” (pp. 134-135)

“As populations grew and competition among people intensified, we began to view group members (both known and unknown, current and past colleagues) as interdependent potential collaborators.

Group members were easily identified by specific cultural practices, and education and conformity to lifestyles became important.

“The collectivization of human life, embodied in cultural practices, norms, and institutions, brought about by new collective thinking, has once again changed the way humans think.” (p. 137)

The Evolution of Thought: A Journey to Find the Missing Link in Human Evolution

The evolutionary history of thought presented in this book is also a process of connecting the “missing links” in the history of thought from apes to humans.

In particular, the book argues that understanding how modern humans think requires looking at it in an evolutionary context.

We must understand how thinking evolved through the evolutionary challenges faced by early and modern humans as they evolved to cooperate for survival.

Tomasello concludes the book with the following conviction:

“My theory of human thought presupposes an evolutionary perspective.

Wittgenstein said this about language:

“Language confuses us not when it is working well, but when it is spinning like an idling engine.” (Wittgenstein, 1995, no.

132) The reason philosophers hit a wall when trying to explain human thought is because they tried to understand it too abstractly, rather than viewing it as an evolutionary adaptation.

Given that many modern people's thoughts seem to lack a clear purpose in some ways, it's natural to think this way.

However, it is almost certain that human-specific thinking was evolutionarily selected for its role in organizing and coordinating behavior.” (p. 232)

This book is a scientific (evolutionary) answer to the question, “Why did human thought arise and how did it evolve?” by world-renowned primatologist Michael Tomasello.

This book deals with the 'scientific (evolutionary) origins' of human thought, which has been perceived as an abstract and conceptual realm.

Professor Jang Dae-ik previously described the author of this book, Tomasello, as “no one on Earth has ever looked so deeply into the subtle gap between humans and other ape species,” and this is no exaggeration.

Tomasello has studied cognition, language acquisition, and cultural formation in primates and humans for over 30 years.

He is currently the director of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, and is also a dedicated and excellent researcher himself.

Tomasello's books and papers have been cited an average of 9,500 times per year over the past five years, and his continued publication of papers annually as first or sole author is a testament to his prominence.

There is an indicator called 'h-index' to refer to the academic contribution of a researcher.

If the h-index is 100, it means that there are more than 100 books or papers that have been cited more than 100 times.

You cannot raise your h-index with papers that are trendy or papers that are only for a living.

To increase your h-index, you must consistently publish papers that are widely cited by your fellow researchers.

According to 'Google Scholar', there are about 2,500 researchers with an h-index of 100 or higher, regardless of field, and only 210 with a score of 150 or higher.

Tomasello's h-index is 159, which is similar to that of Karl Marx (163), who presented one of the most controversial and important issues in human history.

Apes think too, just 'thinking about themselves'

In this book, world-renowned primatologist Tomasello traces the evolutionary history of thought back to before humans diverged from other apes.

Humans share a common ancestor with great apes such as chimpanzees and bonobos.

Humans appear to have split from other apes around 6 million years ago, and Tomasello hypothesizes that humans at this time were no different from apes.

For example, when chimpanzees hunt monkeys, they chase them together in groups.

But it's hard to see the chimpanzees cooperating.

This is because monkeys tend to hunt together and monopolize the food rather than share it with each other.

In this situation, chimpanzee social cognition is competitive rather than cooperative.

Like chimpanzees today, for over 5 million years, human thought was individualistic, operating on social cognition that was both competitive (getting more food) and exploitative (getting as much as possible).

Tomasello explains this with the concept of 'individual intentionality'.

“Imagine a common ancestor between humans and great apes.

Their daily lives were similar to those of present-day apes.

They spent most of their waking hours in small groups, engaged in a variety of social interactions, were largely competitive, and had to forage for food individually.

“My hypothesis is that the common ancestor of apes and humans (and perhaps including Australopithecus, which occupies the first 4 million years of human evolutionary history) was self-oriented and instrumental rational.” (p. 56)

“Individual orientation is primarily necessary for species that engage in competitive social interactions.

They act for themselves, or at best, cooperate temporarily to gain an advantage in a fight.

The social cognitive abilities of great apes evolved primarily to compete with other individuals in groups.

Apes believe in a kind of Machiavellian intelligence.

They viewed group members as future competitors and sought to win the competition.

Recent research suggests that the most complex social cognitive abilities of great apes are driven by competition and exploitation, rather than by cooperation or communication.

“The cognitive abilities of great apes are entirely geared towards competition.” (p. 57)

Why Humans Think Differently From Chimpanzees: Pick a Bad Partner and You'll Starve

It was not until about 400,000 years ago that human thinking began to diverge from that of chimpanzees, from a self-centered, individualistic state.

Tomasello speculates that Homo heidelbergensis was probably the first human to acquire new cognitive skills, and classifies this period as the 'early human' stage.

Early humans set common goals and lived cooperatively in small groups, requiring them to utilize social cognitive functions different from those previously available.

Early humans needed social intelligence to understand the intentions of others, and they began to reflect (think!) on their own communication and actions from the perspective of others.

That is, it was only after almost 5 million years that we began to think of ourselves from the perspective of ‘you’ for the sake of our ‘common (our)’ goal (hunting).

Tomasello distinguishes this from the previous stage, 'individual intentionality', with the concept of 'joint intentionality'.

“Homo heidelbergensis was the common ancestor of Neanderthals and modern humans, and is a hominin that remains enigmatic.

Paleoanthropological evidence suggests that Homo heidelbergensis was the first hominin to systematically cooperate to hunt large animals.

They used weapons that required cooperation, and sometimes brought game home.

This was also a time when brain capacity and population size rapidly increased.

Homo heidelbergensis was a true candidate for cooperation… … Since humans could no longer obtain food on their own, cooperation was necessary.

If we didn't develop new technologies and motivations for cooperation, we would starve to death.

There was a direct and immediate selection pressure on the motivation and skills for cooperative activities (joint orientation).

Second, we began to evaluate others as collaborative partners.

This is a social choice.

If you choose a bad partner, you will starve.

Swindlers and lazy people are avoided, and even scoundrels are avoided.

Early humans faced concerns that other apes did not.

“I began to worry about how I should evaluate others and how others would evaluate me.” (pp. 68-69)

“At some point, early humans began to understand their interdependence with others not only in the context of cooperative activities but also in broader terms, such as the idea that helping a partner not to starve tonight is necessary to ensure that the partner is in good condition for tomorrow’s hunt.” (p. 87)

The Birth of Something Beyond 'Me' and 'You'

About 200,000 years ago, as Homo sapiens entered the era, the scale of cooperation expanded from small 'herds' to 'groups'.

Modern humans have gone a step further than early humans by creating virtual entities called social institutions and endowing them with power.

This means that 'I (the individual)' began to evaluate myself from the group's perspective in order to reveal that I am a being who can perform cooperative activities well as a member of the community.

And moving beyond thinking of you from my perspective, or me from your perspective, we began to think of me and you from the perspective of the group, and of a third party (member).

This explains that humanity has evolved into a different stage from the previous stage (the stage of communal intentionality), and has entered the stage of 'collective intentionality'.

This sociality of 'sharing the group's orientation' that goes beyond me and you has led to a groundbreaking change (evolution) in the thinking of modern humans.

“The small-scale, impromptu cooperation of early humans whenever they needed food was a stable evolutionary strategy.

However, my hypothesis is that over time, two demographic problems arose, necessitating a change in strategy. The first problem was intergroup competition.

To protect their lives from invaders, they had to form proper social groups rather than loose cooperative organizations.

A cooperative group with a common goal of survival (securing food and defending against invasion) and a division of labor system was needed.

This means that group members were motivated to help each other.

Because group members were interdependent, they had an incentive to help each other.

'We' had to join forces to prepare for 'their' invasion.

So individuals began to understand their identity as members of a particular social group that shared a culture.

“A cultural foundation was established based on the orientation of ‘we’ that encompasses the entire group.” (p. 134)

“The second problem was population growth.

As the population grew, several tribes became grouped into a single supergroup, and tribes emerged that shared a single 'culture'.

This means that the problem of how members of a cultural group identify each other has become important.

I had to be able to recognize the other person, but the other person had to be able to recognize me too.

Because only members of a group could share values and cooperate.

In modern human society, group identity is expressed in various ways, but in the beginning it was probably expressed only through behavior.

“People who spoke, cooked, and fished in the same way—that is, people who shared cultural practices—were more likely to belong to the same cultural group.” (pp. 134-135)

“As populations grew and competition among people intensified, we began to view group members (both known and unknown, current and past colleagues) as interdependent potential collaborators.

Group members were easily identified by specific cultural practices, and education and conformity to lifestyles became important.

“The collectivization of human life, embodied in cultural practices, norms, and institutions, brought about by new collective thinking, has once again changed the way humans think.” (p. 137)

The Evolution of Thought: A Journey to Find the Missing Link in Human Evolution

The evolutionary history of thought presented in this book is also a process of connecting the “missing links” in the history of thought from apes to humans.

In particular, the book argues that understanding how modern humans think requires looking at it in an evolutionary context.

We must understand how thinking evolved through the evolutionary challenges faced by early and modern humans as they evolved to cooperate for survival.

Tomasello concludes the book with the following conviction:

“My theory of human thought presupposes an evolutionary perspective.

Wittgenstein said this about language:

“Language confuses us not when it is working well, but when it is spinning like an idling engine.” (Wittgenstein, 1995, no.

132) The reason philosophers hit a wall when trying to explain human thought is because they tried to understand it too abstractly, rather than viewing it as an evolutionary adaptation.

Given that many modern people's thoughts seem to lack a clear purpose in some ways, it's natural to think this way.

However, it is almost certain that human-specific thinking was evolutionarily selected for its role in organizing and coordinating behavior.” (p. 232)

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of publication: December 6, 2017

- Page count, weight, size: 264 pages | 411g | 140*215*20mm

- ISBN13: 9791195650194

- ISBN10: 1195650191

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)