Philosophy of thermometers

|

Description

Book Introduction

Resetting the Field of Science: Complementary Science

We tend to think that science is only about studying cutting-edge things.

On the other hand, some people think that solving the problem is based on facts that have already been revealed.

In this book, Professor Jang Ha-seok presents a new method of scientific activity.

Professor Jang Ha-seok argues that true science is a dynamic process of exploring and revising to arrive at the truth, and that it is not a tool for achieving results, but rather a culture.

He views science as a culture and believes that science can provide an interdisciplinary perspective that transcends the limitations of existing academic disciplines by interacting with the humanities, including history and philosophy, and the arts.

This book presents examples of transdisciplinary scientific activities called 'complementary science'.

Complementary science is a discipline that contributes to scientific knowledge through the study of history and philosophy, and asks scientific questions that are excluded from modern professional science.

Professor Jang Ha-seok presented the history and philosophy of science as research methods for complementary science.

He said, “If you learn about the history of science, you will realize that the relationship between science and technology, and science and other disciplines, is constantly changing.” He added, “In ancient times, science was not only considered a part of philosophy, but it was also closely related to medicine, theology, music, and other fields, so you will be able to understand the various connections between science.”

We tend to think that science is only about studying cutting-edge things.

On the other hand, some people think that solving the problem is based on facts that have already been revealed.

In this book, Professor Jang Ha-seok presents a new method of scientific activity.

Professor Jang Ha-seok argues that true science is a dynamic process of exploring and revising to arrive at the truth, and that it is not a tool for achieving results, but rather a culture.

He views science as a culture and believes that science can provide an interdisciplinary perspective that transcends the limitations of existing academic disciplines by interacting with the humanities, including history and philosophy, and the arts.

This book presents examples of transdisciplinary scientific activities called 'complementary science'.

Complementary science is a discipline that contributes to scientific knowledge through the study of history and philosophy, and asks scientific questions that are excluded from modern professional science.

Professor Jang Ha-seok presented the history and philosophy of science as research methods for complementary science.

He said, “If you learn about the history of science, you will realize that the relationship between science and technology, and science and other disciplines, is constantly changing.” He added, “In ancient times, science was not only considered a part of philosophy, but it was also closely related to medicine, theology, music, and other fields, so you will be able to understand the various connections between science.”

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

The praise poured in for this book

On the publication of the Korean edition

Acknowledgements

A timeline of the history of thermometers

Chapter 1: Fixing the Fixed Point of the Thermometer

History: What to do when water doesn't boil at its boiling point

Blood, Butter, and Deep Cellars: The Necessary but Elusive Anchorage / The Annoying Variety of Boiling Points / Superheating and the Mirage of True Boiling / Escaping Superheating / Understanding Boiling / A Messy Epilogue

Analysis: The Meaning and Achievement of Fixity

Validation of the standard: Top-down justification/ Iterative improvement of the standard: Constructive bottom-up/ Defending the fixedness: Persuasive rejection, unexpected robustness/ Case of freezing point

Chapter 2 Fixing the Fixed Point of the Thermometer

History: In Search of a 'Real' Scale of Temperature

The problem of normative measurement/De Luc and the mixing method/Caloric theory in conflict with the mixing method/The mirage of the caloric theory, linearity of gases/Regnot: Simplicity and comparative equivalence

Analysis: Measurement and Theory in the Context of Empiricism

Step-by-step achievement of observability/Comparative equivalence, and the ontological principle of singular values/Minimalist opposition to Duhemian holism/Regnot, and post-Laplace empiricism

Chapter 3: Moving Beyond

History: Measuring Temperatures When a Thermometer Melts and Freezes

Can mercury freeze? / Can mercury show its freezing point? / Solidifying the freezing point of mercury / The adventures of a scientific potter / Is that not the temperature we know? / The collective criticism of Wedgwood

Analysis: Expanding the Concept Beyond Birthplace

Percy Bridgman's Travel Guide / Beyond Bridgman: Meaning, Definition, Validity / Strategies for Expansion: Strategies for Growth, Supporting Each Other

Chapter 4 Theory, Measurement, and Absolute Temperature

History: In search of the theoretical meaning of temperature

Temperature, heat, and cold Theoretical temperature before thermodynamics / William Thomson's move toward the abstract / Thomson's second absolute temperature / Partially concrete Carnot cycle model / Approximating absolute temperature using a gas thermometer

Analysis: Operationalization - Creating Contact Between Objects and Actions

The Hidden Difficulties of Reduction / Handling Abstract Concepts / Operationalization and Its Validity / Precision through Repetition / Theoretical Temperature without Thermodynamics

Chapter 5: Measurement, Justification, and the Progress of Science

Measurement, Circulation, and Coherence/ Making Coherence Progress: Epistemic Iteration/ The Fruits of Iteration: Enrichment and Self-Correction/ Tradition, Progress, and Pluralism/ The Abstract and the Concrete

Chapter 6: Complementary Science - A Different Way of Expanding Science: History and Philosophy of Science

The complementary functions of the history and philosophy of science / The interaction between philosophy, history, and complementary science / The nature of the knowledge produced by complementary science / In relation to other research fields in the history and philosophy of science / Other paths to science

Explanation of scientific, historical, and philosophical terms

Translator's Note

Reviewer's note

References

Search

On the publication of the Korean edition

Acknowledgements

A timeline of the history of thermometers

Chapter 1: Fixing the Fixed Point of the Thermometer

History: What to do when water doesn't boil at its boiling point

Blood, Butter, and Deep Cellars: The Necessary but Elusive Anchorage / The Annoying Variety of Boiling Points / Superheating and the Mirage of True Boiling / Escaping Superheating / Understanding Boiling / A Messy Epilogue

Analysis: The Meaning and Achievement of Fixity

Validation of the standard: Top-down justification/ Iterative improvement of the standard: Constructive bottom-up/ Defending the fixedness: Persuasive rejection, unexpected robustness/ Case of freezing point

Chapter 2 Fixing the Fixed Point of the Thermometer

History: In Search of a 'Real' Scale of Temperature

The problem of normative measurement/De Luc and the mixing method/Caloric theory in conflict with the mixing method/The mirage of the caloric theory, linearity of gases/Regnot: Simplicity and comparative equivalence

Analysis: Measurement and Theory in the Context of Empiricism

Step-by-step achievement of observability/Comparative equivalence, and the ontological principle of singular values/Minimalist opposition to Duhemian holism/Regnot, and post-Laplace empiricism

Chapter 3: Moving Beyond

History: Measuring Temperatures When a Thermometer Melts and Freezes

Can mercury freeze? / Can mercury show its freezing point? / Solidifying the freezing point of mercury / The adventures of a scientific potter / Is that not the temperature we know? / The collective criticism of Wedgwood

Analysis: Expanding the Concept Beyond Birthplace

Percy Bridgman's Travel Guide / Beyond Bridgman: Meaning, Definition, Validity / Strategies for Expansion: Strategies for Growth, Supporting Each Other

Chapter 4 Theory, Measurement, and Absolute Temperature

History: In search of the theoretical meaning of temperature

Temperature, heat, and cold Theoretical temperature before thermodynamics / William Thomson's move toward the abstract / Thomson's second absolute temperature / Partially concrete Carnot cycle model / Approximating absolute temperature using a gas thermometer

Analysis: Operationalization - Creating Contact Between Objects and Actions

The Hidden Difficulties of Reduction / Handling Abstract Concepts / Operationalization and Its Validity / Precision through Repetition / Theoretical Temperature without Thermodynamics

Chapter 5: Measurement, Justification, and the Progress of Science

Measurement, Circulation, and Coherence/ Making Coherence Progress: Epistemic Iteration/ The Fruits of Iteration: Enrichment and Self-Correction/ Tradition, Progress, and Pluralism/ The Abstract and the Concrete

Chapter 6: Complementary Science - A Different Way of Expanding Science: History and Philosophy of Science

The complementary functions of the history and philosophy of science / The interaction between philosophy, history, and complementary science / The nature of the knowledge produced by complementary science / In relation to other research fields in the history and philosophy of science / Other paths to science

Explanation of scientific, historical, and philosophical terms

Translator's Note

Reviewer's note

References

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

Doing science should be about asking your own questions, conducting your own investigations, and drawing your own conclusions based on your own evidence.

Of course, it would be impossible to develop the 'cutting edge' or 'frontier' of modern science without first undergoing several years of specialized training.

But science isn't always about cutting edge, nor is it necessarily the most valuable part of science.

Questions that have been answered are still worth asking again.

In this way, you can teach yourself how to arrive at standard answers, and possibly discover new ones or recover valuable but forgotten answers.

--- p.30

The direct and easy lesson to be learned from the story of frozen mercury is that when we go beyond the realm of familiar phenomena, the unexpected can and does happen.

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), a utilitarian lawyer, used this example to explain how our willingness to believe is tied to familiarity.

When Bentham told the story of Brown's experiment to a "learned doctor" living in London, the response he received was as follows:

“With the air of authority that old men are wont to assume when conversing with young men, [he] declared the story to be false, and said that he ought to be ashamed of himself for attempting to prove it in any way.” Bentham compared this story to a story of a German traveler (reported by John Locke).

The traveler told the King of Siam that in the Netherlands, water solidifies in winter and people and carriages travel on it, and was scolded by the King “with a contemptuous laugh.”

--- pp.222

Self-correction, another key aspect of iterative progress, can also be explained first with a story from everyday life (though this explanation contains a bit of exaggeration).

Without my glasses, I have trouble focusing my eyes on small or dim objects.

So when you take your glasses off to inspect them, you can't see the tiny scratches and smudges on them.

However, if you wear the same glasses and stand in front of a mirror, you can see the details of the lenses very well.

In short, my glasses can show me their own flaws.

This is the amazing power of self-correction.

But how can I trust the image I see through those same flawed glasses? First, my belief stems from the clarity of my senses and the clarity of the image itself, regardless of how it was obtained.

Because of this, I can accept that certain flaws in my glasses do not affect the quality of the image I see (even when the image is about the flaw itself).

But there is also a deeper layer to this self-correction mechanism.

At first I was delighted that my glasses could still give me a clear and detailed image even though they had flaws, but upon further observation I noticed that some of the flaws sometimes distorted the image to a perceptible degree.

Once I become aware of that, I can try to correct the distortion.

(…) We have seen many examples of self-correction.

The clearest examples are found in the methods of Calendar and Le Chatelier, who operationalized the concept of absolute temperature.

The initial assumption that real gases obey the ideal gas law was used to calculate the extent to which real gases deviate from that law.

--- pp.442-443

While Kuhn's account of "normal science" assumed that scientists within a particular scientific discipline are given only one paradigm, I believe we should acknowledge that orthodoxy can be rejected without invoking nihilism if we can find an alternative, already existing system that can be verified as the basis for our research.

That alternative system could be an early version of the current orthodoxy, a long-forgotten framework unearthed from the history of science, or something imported from a very different tradition.

Kuhn persuasively argued that a paradigm shift occurs when an orthodox paradigm is maintained and pushed forward, and then broken.

However, he did not argue that believing in and following one paradigm is the only reasonable or even the most effective way to move to another paradigm.

(…) Even if we consider only the improvement of a single cognitive virtue, there are many different ways to achieve it, and there will be more than one way to achieve it equally well.

Often we become so obsessed with truth that we shy away from this pluralistic understanding, believing that incompatible knowledge systems cannot all be true.

The achievement of other virtues is not so exclusive.

There may also be different paths to improving specific epistemic virtues (e.g., explanatory power or numerical accuracy of measurement) related to beliefs about mutually incompatible propositions.

Generally speaking, if we view the advancement of existing knowledge as a creative achievement, it is not so disturbing that the direction of such achievement is open to many options.

--- pp.445-447

What initially drew me to this field and still drives me is a curious combination of excitement and frustration, enthusiasm and skepticism about science.

What keeps me going is the wonder of seeing logic and beauty in conceptual systems that at first seemed foreign and nonsensical.

It is the awe you feel when you look into an everyday experimental device and realize that it is truly a masterpiece, that within it the errors cancel each other out and that the knowledge information is squeezed out of nature like water from a stone.

It is also the frustration and anger that comes when other conceptual frameworks are neglected and suppressed, when I stare at endless calculations where the meaning of basic terms never becomes clear, when I am forced to accept and trust laboratory equipment when I do not have the time or expertise to learn and understand its mechanisms.

--- p.6

I have argued that complementary science can generate scientific knowledge in areas where science itself cannot.

This may sound strange.

How can knowledge about nature be produced through historical or philosophical research? And if complementary science produces scientific knowledge, shouldn't it simply be considered a part of science? Furthermore, isn't it absurd to suggest that such scientific activity can be performed by anyone, not just properly trained professionals? It's understandable, even if it feels absurd.

But I believe that if we consider more carefully what it means to produce knowledge, we can shake off that feeling of absurdity.

--- p.465

Complementary science could trigger a decisive transformation in the nature of our scientific knowledge.

With the expanding and diversifying current body of expert knowledge, we can create more complementary knowledge systems that combine the regeneration of older sciences, new judgments about past and present science, and the exploration of alternatives.

This kind of knowledge will be accessible to non-experts as well.

It may also be useful, or at least interesting, to current experts, as it can show the reasons behind the acceptance of the basic contents of scientific knowledge.

While it may interfere with the research of experts in that it erodes blind faith in fundamentals, I believe it actually produces beneficial effects overall.

Above all, the field that will produce the most novel and interesting effects is education.

Complementary science can serve as a pillar of science education, contributing to the needs of general education as well as pre-professional training.

It is a very big step forward, and it will allow an educated public to once again participate in building knowledge about our universe.

Of course, it would be impossible to develop the 'cutting edge' or 'frontier' of modern science without first undergoing several years of specialized training.

But science isn't always about cutting edge, nor is it necessarily the most valuable part of science.

Questions that have been answered are still worth asking again.

In this way, you can teach yourself how to arrive at standard answers, and possibly discover new ones or recover valuable but forgotten answers.

--- p.30

The direct and easy lesson to be learned from the story of frozen mercury is that when we go beyond the realm of familiar phenomena, the unexpected can and does happen.

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), a utilitarian lawyer, used this example to explain how our willingness to believe is tied to familiarity.

When Bentham told the story of Brown's experiment to a "learned doctor" living in London, the response he received was as follows:

“With the air of authority that old men are wont to assume when conversing with young men, [he] declared the story to be false, and said that he ought to be ashamed of himself for attempting to prove it in any way.” Bentham compared this story to a story of a German traveler (reported by John Locke).

The traveler told the King of Siam that in the Netherlands, water solidifies in winter and people and carriages travel on it, and was scolded by the King “with a contemptuous laugh.”

--- pp.222

Self-correction, another key aspect of iterative progress, can also be explained first with a story from everyday life (though this explanation contains a bit of exaggeration).

Without my glasses, I have trouble focusing my eyes on small or dim objects.

So when you take your glasses off to inspect them, you can't see the tiny scratches and smudges on them.

However, if you wear the same glasses and stand in front of a mirror, you can see the details of the lenses very well.

In short, my glasses can show me their own flaws.

This is the amazing power of self-correction.

But how can I trust the image I see through those same flawed glasses? First, my belief stems from the clarity of my senses and the clarity of the image itself, regardless of how it was obtained.

Because of this, I can accept that certain flaws in my glasses do not affect the quality of the image I see (even when the image is about the flaw itself).

But there is also a deeper layer to this self-correction mechanism.

At first I was delighted that my glasses could still give me a clear and detailed image even though they had flaws, but upon further observation I noticed that some of the flaws sometimes distorted the image to a perceptible degree.

Once I become aware of that, I can try to correct the distortion.

(…) We have seen many examples of self-correction.

The clearest examples are found in the methods of Calendar and Le Chatelier, who operationalized the concept of absolute temperature.

The initial assumption that real gases obey the ideal gas law was used to calculate the extent to which real gases deviate from that law.

--- pp.442-443

While Kuhn's account of "normal science" assumed that scientists within a particular scientific discipline are given only one paradigm, I believe we should acknowledge that orthodoxy can be rejected without invoking nihilism if we can find an alternative, already existing system that can be verified as the basis for our research.

That alternative system could be an early version of the current orthodoxy, a long-forgotten framework unearthed from the history of science, or something imported from a very different tradition.

Kuhn persuasively argued that a paradigm shift occurs when an orthodox paradigm is maintained and pushed forward, and then broken.

However, he did not argue that believing in and following one paradigm is the only reasonable or even the most effective way to move to another paradigm.

(…) Even if we consider only the improvement of a single cognitive virtue, there are many different ways to achieve it, and there will be more than one way to achieve it equally well.

Often we become so obsessed with truth that we shy away from this pluralistic understanding, believing that incompatible knowledge systems cannot all be true.

The achievement of other virtues is not so exclusive.

There may also be different paths to improving specific epistemic virtues (e.g., explanatory power or numerical accuracy of measurement) related to beliefs about mutually incompatible propositions.

Generally speaking, if we view the advancement of existing knowledge as a creative achievement, it is not so disturbing that the direction of such achievement is open to many options.

--- pp.445-447

What initially drew me to this field and still drives me is a curious combination of excitement and frustration, enthusiasm and skepticism about science.

What keeps me going is the wonder of seeing logic and beauty in conceptual systems that at first seemed foreign and nonsensical.

It is the awe you feel when you look into an everyday experimental device and realize that it is truly a masterpiece, that within it the errors cancel each other out and that the knowledge information is squeezed out of nature like water from a stone.

It is also the frustration and anger that comes when other conceptual frameworks are neglected and suppressed, when I stare at endless calculations where the meaning of basic terms never becomes clear, when I am forced to accept and trust laboratory equipment when I do not have the time or expertise to learn and understand its mechanisms.

--- p.6

I have argued that complementary science can generate scientific knowledge in areas where science itself cannot.

This may sound strange.

How can knowledge about nature be produced through historical or philosophical research? And if complementary science produces scientific knowledge, shouldn't it simply be considered a part of science? Furthermore, isn't it absurd to suggest that such scientific activity can be performed by anyone, not just properly trained professionals? It's understandable, even if it feels absurd.

But I believe that if we consider more carefully what it means to produce knowledge, we can shake off that feeling of absurdity.

--- p.465

Complementary science could trigger a decisive transformation in the nature of our scientific knowledge.

With the expanding and diversifying current body of expert knowledge, we can create more complementary knowledge systems that combine the regeneration of older sciences, new judgments about past and present science, and the exploration of alternatives.

This kind of knowledge will be accessible to non-experts as well.

It may also be useful, or at least interesting, to current experts, as it can show the reasons behind the acceptance of the basic contents of scientific knowledge.

While it may interfere with the research of experts in that it erodes blind faith in fundamentals, I believe it actually produces beneficial effects overall.

Above all, the field that will produce the most novel and interesting effects is education.

Complementary science can serve as a pillar of science education, contributing to the needs of general education as well as pre-professional training.

It is a very big step forward, and it will allow an educated public to once again participate in building knowledge about our universe.

--- p.482

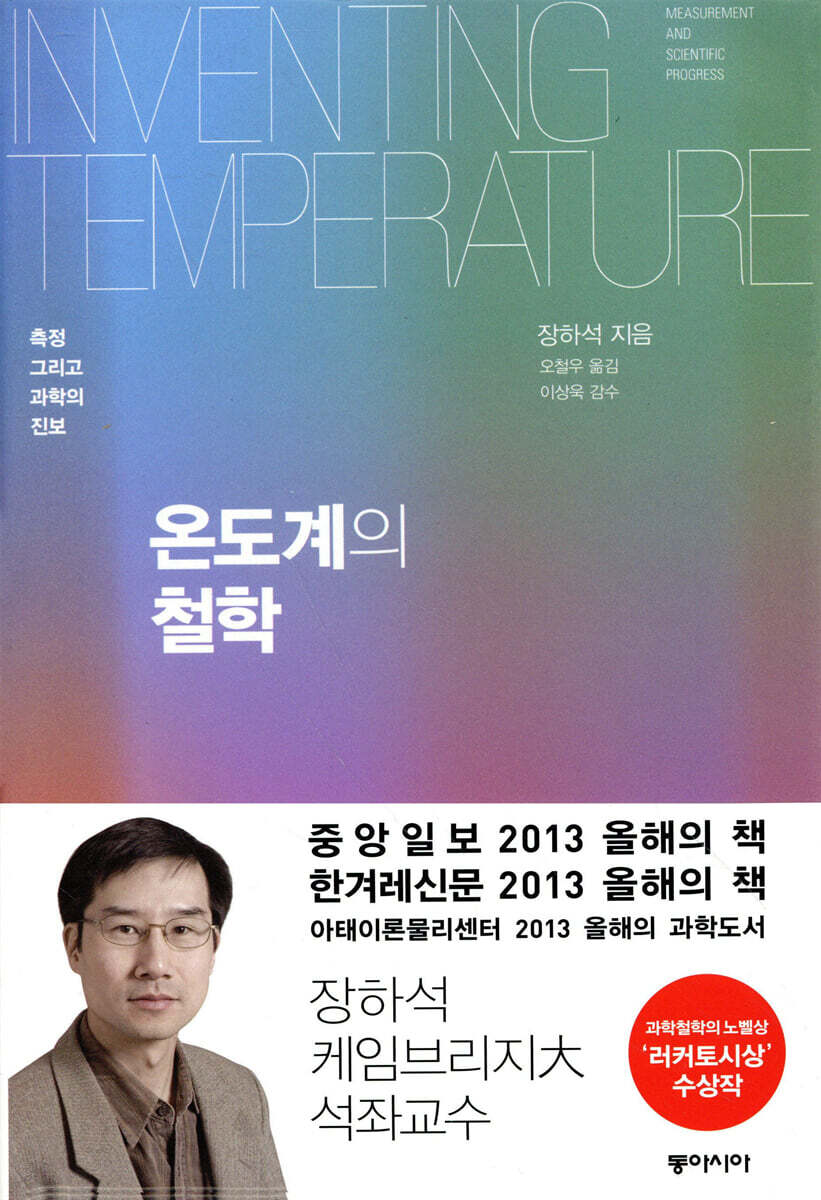

Publisher's Review

The 21st century's Thomas Kuhn, Professor Ha-seok Chang's greatest accomplishment.

Inventing Temperature won the Lakatos Award, given to the best book on the philosophy of science.

This book deals with how temperature was measured, the concept was created, and the invention of the thermometer in a time when there was no thermometer.

This book, which started with the curiosity of “How can we measure the temperature of a thermometer that measures temperature?”, has become a must-read in both the history and philosophy of science, and is evaluated as a book that has broadened the horizons of science by reviving important scientific challenges that were forgotten as science advanced.

Through the book, Professor Ha-seok Chang of Cambridge University became known as a world-renowned philosopher of science, and received not only the Lakatosh Prize but also the Ivan Slade Prize, awarded by the British Society for the History of Science in 2005 to the author of an essay that has made the most significant contribution to the history of science.

In the same year, he was also a finalist for the Times Higher Education Supplement (THES) Young Academic Author of the Year award.

The Philosophy of Thermometers has been compared to the works of Thomas Kuhn.

Professor Jang Ha-seok finished middle school in Seoul and moved to the United States. He graduated at the top of his class from Northfield Mount Hermann High School, a prestigious high school in the United States, in two years, and studied physics and philosophy at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech).

He received his Ph.D. in philosophy from Stanford University with a dissertation on “Measurement and Non-Unity in Quantum Physics” and completed his post-doctoral studies at Harvard University.

In 1995, at the age of 28, he was appointed professor at the University of London, and in 2004, he published “The Philosophy of Thermometers.”

In 2010, at the age of early 40, he was invited to become a distinguished professor at Cambridge University.

The first Korean to become a Cambridge professor, his older brother Ha-Joon Chang is also a professor at the same university.

Professor Jang Ha-seok became famous overnight as a world-renowned philosopher of science through his book, “The Philosophy of Thermometers.”

The Lakatos Prize, which 『Philosophy of the Thermometer』 won, was established to commemorate and celebrate the achievements of the Hungarian philosopher of science Imre Lakatos. It is awarded to the best English-language book in the field of philosophy of science published in the past six years.

Professor Jang Ha-seok is also a scholar of the history of science who writes excellent papers that are so rare that they have won the Ivan Slade Award in the field of scientific history, which is a rare feat for a philosopher of science.

Professor Lee Sang-wook of Hanyang University said, “There are few people in the world who are recognized for their outstanding research abilities in both the history and philosophy of science as Professor Jang Ha-seok.”

This is why Professor Choi Jae-cheon of Ewha Womans University evaluated Professor Jang Ha-seok as “the Thomas Kuhn of the 21st century.”

Just like Thomas Kuhn, who simultaneously studied the history and philosophy of science to derive the innovative concept of “paradigm,” Professor Jang Ha-seok is also producing excellent research results, including “The Philosophy of the Thermometer.”

Thanks to these achievements, Professor Jang Ha-seok was invited to the Hans Rausing Chair at Cambridge University in 2010 at the age of early 40, a position he holds to this day.

The Hans Rausing Chair is the most senior of the ten professors in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge. The position was created through a donation from the Rausing family, owners of the Tetra Laval Group, famous for its paper packs.

It was the first time that a Korean had held a permanent professorship at Cambridge University.

Professor Ha-seok Jang, the second son of former Minister of Trade, Industry and Energy Jae-sik Jang, is the younger brother of Ha-joon Chang, a professor of economics at Cambridge University. Former Minister of Gender Equality and Family Jang Ha-jin and Professor Ha-sung Jang of Korea University are also his cousins.

His family is also famous as a noble family of the Indong Jang clan, which has dedicated itself to the independence movement and Korea's development for generations.

Also, his brother-in-law is former senior prosecutor Lim Su-bin (now a lawyer), who is famous as the “[PD Notebook] prosecutor” for investigating the mad cow disease report case on MBC’s “PD Notebook.”

In 2011, brothers Ha-seok Chang and Ha-joon Chang were selected by the Dong-A Ilbo as one of the '100 People Who Will Shine in Korea in 10 Years'.

2.

Introduction and significance of "The Philosophy of the Thermometer"

The result of a great study that started from an 8-year-old's question.

"The Philosophy of the Thermometer" begins by asking why we accept the fundamental truths of science that we have been taught and take for granted.

Professor Jang Ha-seok said in an interview with domestic media, “Now we use the word ‘electricity’ as a matter of course, but at first it was such an unfamiliar and difficult word.

Let me give you an example.

"Why does static electricity occur? It's because of free electrons. Where do free electrons come from?" he asked.

Professor Jang Ha-seok noted that we use words like electricity and temperature so easily and naturally, but when we ask ourselves what they mean, they feel very unfamiliar and difficult.

Among various common-sense scientific concepts, Professor Jang Ha-seok paid particular attention to 'temperature' and asked a question like that of an eight-year-old: "When measuring temperature using a thermometer, how can we measure the temperature of the thermometer that measures temperature?"

The answer to this seemingly simple question was not immediately apparent.

Professor Jang Ha-seok said in his “Notes on the Publication of the Korean Edition” of the book, “Modern physics does not even address such trivial issues, and epistemological thinking has not yielded any answers.”

So, Professor Jang Ha-seok studied the history of science to understand the foundations of scientific knowledge, and since many important achievements at the time came from France, he even learned French.

Even after researching like this, the answer to the above question did not come easily.

Professor Jang Ha-seok was deeply immersed in temperature and thermometers for a long time, and it took exactly 10 years for him to finally publish “The Philosophy of Thermometers.”

You might ask, “Do you have a thermometer?”

To this question, Professor Jang Ha-seok said this:

“If you delve deep into learning, it’s all like that.”

Resetting the Field of Science: Complementary Science

We tend to think that science is only about studying cutting-edge things.

On the other hand, some people think that solving the problem is based on facts that have already been revealed.

In this book, Professor Jang Ha-seok presents a new method of scientific activity.

Professor Jang Ha-seok argues that true science is a dynamic process of exploring and revising to arrive at the truth, and that it is not a tool for achieving results, but rather a culture.

He views science as a culture and believes that science can provide a transdisciplinary perspective that transcends the limitations of existing academic disciplines by interacting with the humanities, including history and philosophy, and the arts.

This book presents examples of transdisciplinary scientific activities called 'complementary science'.

Complementary science is a discipline that contributes to scientific knowledge through the study of history and philosophy, and asks scientific questions that are excluded from modern professional science.

Professor Jang Ha-seok presented the history and philosophy of science as research methods for complementary science.

“If you learn about the history of science, you will realize that the relationship between science and technology, and science and other disciplines, is constantly changing,” he said in an interview with domestic media. “In ancient times, science was not only considered a part of philosophy, but it was also closely related to medicine, theology, music, etc., so you will be able to understand the various connections between science.”

Reviving the great currents of philosophy and science through the history of science

"The Philosophy of Thermometers" traces the development of various temperature measurement systems before the concept of Celsius used in Korea, Fahrenheit used in the United States, and absolute temperature used by physicists.

It contains the struggle to establish fixed points for the thermometer, such as the boiling point and freezing point, as well as the efforts to establish a numerical thermometer by drawing the thermometer scale after over a century of debate and experimentation.

Next, we discussed the method of measuring temperature at extreme high or low temperatures beyond the range that a mercury thermometer can measure, and the process of its theoretical development.

This series of events was not an easy task and took 200 years.

Think about it for a moment.

To fix a fixed point, we need to know what boiling is, and we need to fix a standard point among the boiling points that fluctuate depending on various factors including pressure.

And unlike the red line in the mercury thermometers we use, thermometers of the past did not expand linearly with temperature.

Also, the thermometers of that time would freeze in extreme cold and melt in hot places such as inside a pottery kiln.

The history of the thermometer was more difficult than we thought, and in the process of overcoming it, great heroes emerged, such as Fahrenheit, famous for the Fahrenheit thermometer, Celsius for the Celsius thermometer, Black who measured latent heat, Irvine who developed the theory of heat capacity, de Luc and Cavendish who fixed the boiling point, Wedgwood, a master of ceramics, and William Thomson who established the modern theory of thermodynamics.

While telling an interesting story about the development of temperature measurement, Professor Jang Ha-seok revealed through a meticulous scientific study of the history of temperature measurement that the process of temperature measurement was a meaningful scientific undertaking that revealed many new phenomena that had not yet been explained.

And he explained philosophically that in the process of determining absolute temperature, it was inevitable to introduce several metaphysical assumptions and conventions.

This showed that scientific theories objectively capture the characteristics of nature, but also reflect the scientific views of the individual scientists who create the theories.

A great achievement representing the 21st century philosophy of science

Professor Jang Ha-seok's research style is similar to that of Thomas Kuhn (1992-1996), who left a significant mark on both the history and philosophy of science.

Thomas Kuhn showed that those who had argued for geocentrism before Copernicus were not simply mistaken or stubborn, but rather supported geocentrism under intense empirical evidence and theoretical conditions.

Professor Jang Ha-seok also shows that even before the invention of the current thermometer, people who created their own thermometers chose and researched temperature measurement methods in an extremely rational manner.

Professor Jang Ha-seok also argues that scientists choose one theory among competing theories by comprehensively considering conflicting empirical evidence and various theoretical conditions, and that even though the vast majority of scientists perform the selection process extremely rationally, they can still have different opinions.

Professor Jang Ha-seok rediscovered the French scientist Victor Regnault and used it as an example to explain his argument.

Although not well known to us today, Regnault was a scholar who held a dominant position in the 19th-century European physics community.

Even William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin), who perfected the concept of absolute temperature, trained in his laboratory and left a tribute to Regnault.

He developed an argument for selecting a fluid for accurate temperature measurement through very precise experiments.

Research on these temperature measurements was quickly and widely accepted in Europe at the time.

His reasoning was impeccable, his technique unparalleled.

The thoroughness of the experimental process was even more evident.

And he skillfully avoided theoretical criticism.

However, the theoretical definition of absolute temperature was established by William Thomson, who had trained in Regnault's laboratory in his youth, and Regnault's research was quickly forgotten.

Just because Renault was overshadowed by Thompson, it doesn't mean his research was meaningless.

Professor Jang Ha-seok, through the history of competing concepts of temperature and the various manipulations (or implementations) to empirically measure it, has re-asked and presented more systematic answers to questions that are considered philosophical in the 'narrow' sense of modern science, but were in fact excellent 'scientific' questions without controversy to scientists of the past.

This is in line with his belief that the history and philosophy of science can be a 'complement' to modern science through 'doing science' in a different sense.

Scientific activity as true integration

Professor Jang Ha-seok concludes his book by arguing that complementary science can trigger a decisive transformation in the nature of our scientific knowledge through this process:

With the expanding and diversifying current body of expert knowledge, we can create more complementary knowledge systems that combine the regeneration of older sciences, new judgments about past and present science, and the exploration of alternatives.

This kind of knowledge will be accessible to non-experts as well.

It may also be useful, or at least interesting, to current experts, as it may show the reasons behind the acceptance of the basic contents of scientific knowledge.

While it may interfere with the research of experts in that it erodes blind faith in fundamentals, I believe it actually produces beneficial effects overall.

3. Structure and Summary of "The Philosophy of the Thermometer"

A science book for both scholars and general readers

Although this book is academic, it can also be of interest to non-specialist readers.

Professor Jang Ha-seok explained in his “Notes on the Publication of the Korean Edition” that he devoured Carl Sagan’s “Cosmos” as a child, and that the book not only fostered his passion for science but also shaped his political and philosophical worldview.

So, like Cosmos, he structured it so that it could be accessible to all readers interested in science, using friendly analogies to explain things and adding various photos, illustrations, and tables to keep readers interested and engaged.

Chapters 1 through 4 cover the history and philosophy of scientific knowledge about temperature, which is now taken for granted.

These chapters are divided into narrative and analytical parts, the historical part covering the development of the thermometer and the subsequent philosophical debates of the time.

The analysis section covers broader philosophical and historical topics than the historical section above, and separates out in-depth discussions that might disrupt the flow of history.

Chapter 5 organizes the previous four chapters into a systematic and explicit philosophical discussion.

Chapter 6 clearly states what the author hopes to achieve through research such as that in this book.

Professor Jang Ha-seok recommended that if you are interested in history, you can read only the history section of the first four chapters, and that you read the analysis section of the four chapters according to your specific interests.

If you find the detailed historical part difficult to endure, you can just read the analysis part of Chapters 1-4 and Chapter 5.

Chapter 6 is primarily intended for professional scholars and students in the philosophy of science, and is recommended for those who are interested in the research presented in the preceding chapters, or who find such research activities perplexing or confusing.

[Summary of each chapter]

Chapter 1: Fixing the Fixed Point of the Thermometer

We rediscover and reacquaint ourselves with the old challenge of finding the fixed point of the thermometer, now forgotten and unrealistic.

History: What to do when water doesn't boil at its boiling point

It contains a historical account of the remarkable challenges scientists faced and overcame as they worked to establish a fixed point: the boiling point of water.

The struggles primarily concerned the task of establishing fixed points for temperature measurement.

Analysis: The Meaning and Achievement of Fixity

We have philosophically examined what it really means for a phenomenon to become a fixed point, and how fixity can be determined if there are no established standards.

We also discuss what implicit standards are employed in the successful construction of anchor points and the cognitive strategies used to defend anchor points and their standards.

In addition, we also looked at the case of freezing points that are different from boiling points.

Chapter 2: Spirits, Air, and Mercury

History: In Search of a 'Real' Scale of Temperature

It contains the scientific efforts to establish a numerical thermometer and the process of resolving philosophical difficulties that were overcome after over a century of debate and experimentation.

Once the anchor points are established at a reasonable level, we describe a procedure for numbering the intervals between the anchor points and the ranks of the columns outside them.

Analysis: Measurement and Theory in the Context of Empiricism

It deals with Regnault, who experimentally and cognitively implemented the most perfect practical thermometry method of his time, and made progress from thermoscope to numerical thermometer.

Renault expanded the scope of observability and responsibly explored the metaphysics of temperature measurement.

Regnault's achievements were the pinnacle of empiricism after Laplace.

Chapter 3: Moving Beyond

History: Measuring Temperatures When a Thermometer Melts and Freezes

It contains the process of extending the scale of a numerical thermometer beyond its established temperature range.

When mercury freezes or boils, the thermometer breaks or melts.

How should the temperature be measured at this time? This section covers how the highest and lowest temperature points are handled.

One is the study of the freezing point of mercury, and the other is the efforts of the master potter Wedgwood to create a thermometer that could measure the temperature of a kiln.

Analysis: Expanding the Concept Beyond Birthplace

We discuss the philosophical justification for extending established knowledge beyond its domain and the key issues surrounding the meaning of such work.

Here, I use a perspective that revives Percy Bridgman's operationalist philosophy to further explain the process by which a concept extends beyond the realm of phenomena it initially describes.

Chapter 4 Theory, Measurement, and Absolute Temperature

History: In search of the theoretical meaning of temperature

Looking at the three previous chapters, we can see that the study of temperature measurement was conducted without a precise theory of temperature or heat.

Until the mid-19th century, most temperature measurements were made without much theoretical understanding.

Chapter 4's historical section shows why the connection between thermometry and heat theory was so difficult, and how that connection was successfully achieved.

This book covers classical thermodynamics, excluding recent thermodynamic theories such as statistical thermodynamics.

Analysis: Operationalization - Creating Contact Between Objects and Actions

Once a theory is developed, its empirical significance must be verified and its verifiability must be examined.

To do this, we need to connect abstract theoretical structures with physical operations.

In this process of connection, meanings that did not exist before are created.

Thomson's absolute temperature can also be said to be a newly born operational meaning. In this section, we look back on the history of Thomson's attempts to measure absolute temperature, examine the operationalizations he performed, and discuss whether these operationalizations were carried out well.

Chapter 5: Measurement, Justification, and the Progress of Science

When we try to justify our measurement methods, we discover the circle inherent in empiricist foundationalism.

The only productive way to deal with such a cycle is to accept it and acknowledge that justification within empirical science cannot but support coherentism.

Within such coherence theory, epistemic repetition becomes an effective way to achieve scientific progress, ultimately enriching and self-correcting the initially identified system.

This way of making scientific progress embraces both conservatism and pluralism.

Chapter 6: Complementary Science—Extended Science in a Different Way: History and Philosophy of Science

We aim to demonstrate that complementary science is a productive direction for the history and philosophy of science.

Complementary science could trigger a decisive transformation in the nature of our scientific knowledge.

In addition to the expanding and diversifying current professional knowledge, we can create more new knowledge systems by reviving old science, making new judgments about past and present science, and exploring alternatives.

Inventing Temperature won the Lakatos Award, given to the best book on the philosophy of science.

This book deals with how temperature was measured, the concept was created, and the invention of the thermometer in a time when there was no thermometer.

This book, which started with the curiosity of “How can we measure the temperature of a thermometer that measures temperature?”, has become a must-read in both the history and philosophy of science, and is evaluated as a book that has broadened the horizons of science by reviving important scientific challenges that were forgotten as science advanced.

Through the book, Professor Ha-seok Chang of Cambridge University became known as a world-renowned philosopher of science, and received not only the Lakatosh Prize but also the Ivan Slade Prize, awarded by the British Society for the History of Science in 2005 to the author of an essay that has made the most significant contribution to the history of science.

In the same year, he was also a finalist for the Times Higher Education Supplement (THES) Young Academic Author of the Year award.

The Philosophy of Thermometers has been compared to the works of Thomas Kuhn.

Professor Jang Ha-seok finished middle school in Seoul and moved to the United States. He graduated at the top of his class from Northfield Mount Hermann High School, a prestigious high school in the United States, in two years, and studied physics and philosophy at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech).

He received his Ph.D. in philosophy from Stanford University with a dissertation on “Measurement and Non-Unity in Quantum Physics” and completed his post-doctoral studies at Harvard University.

In 1995, at the age of 28, he was appointed professor at the University of London, and in 2004, he published “The Philosophy of Thermometers.”

In 2010, at the age of early 40, he was invited to become a distinguished professor at Cambridge University.

The first Korean to become a Cambridge professor, his older brother Ha-Joon Chang is also a professor at the same university.

Professor Jang Ha-seok became famous overnight as a world-renowned philosopher of science through his book, “The Philosophy of Thermometers.”

The Lakatos Prize, which 『Philosophy of the Thermometer』 won, was established to commemorate and celebrate the achievements of the Hungarian philosopher of science Imre Lakatos. It is awarded to the best English-language book in the field of philosophy of science published in the past six years.

Professor Jang Ha-seok is also a scholar of the history of science who writes excellent papers that are so rare that they have won the Ivan Slade Award in the field of scientific history, which is a rare feat for a philosopher of science.

Professor Lee Sang-wook of Hanyang University said, “There are few people in the world who are recognized for their outstanding research abilities in both the history and philosophy of science as Professor Jang Ha-seok.”

This is why Professor Choi Jae-cheon of Ewha Womans University evaluated Professor Jang Ha-seok as “the Thomas Kuhn of the 21st century.”

Just like Thomas Kuhn, who simultaneously studied the history and philosophy of science to derive the innovative concept of “paradigm,” Professor Jang Ha-seok is also producing excellent research results, including “The Philosophy of the Thermometer.”

Thanks to these achievements, Professor Jang Ha-seok was invited to the Hans Rausing Chair at Cambridge University in 2010 at the age of early 40, a position he holds to this day.

The Hans Rausing Chair is the most senior of the ten professors in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge. The position was created through a donation from the Rausing family, owners of the Tetra Laval Group, famous for its paper packs.

It was the first time that a Korean had held a permanent professorship at Cambridge University.

Professor Ha-seok Jang, the second son of former Minister of Trade, Industry and Energy Jae-sik Jang, is the younger brother of Ha-joon Chang, a professor of economics at Cambridge University. Former Minister of Gender Equality and Family Jang Ha-jin and Professor Ha-sung Jang of Korea University are also his cousins.

His family is also famous as a noble family of the Indong Jang clan, which has dedicated itself to the independence movement and Korea's development for generations.

Also, his brother-in-law is former senior prosecutor Lim Su-bin (now a lawyer), who is famous as the “[PD Notebook] prosecutor” for investigating the mad cow disease report case on MBC’s “PD Notebook.”

In 2011, brothers Ha-seok Chang and Ha-joon Chang were selected by the Dong-A Ilbo as one of the '100 People Who Will Shine in Korea in 10 Years'.

2.

Introduction and significance of "The Philosophy of the Thermometer"

The result of a great study that started from an 8-year-old's question.

"The Philosophy of the Thermometer" begins by asking why we accept the fundamental truths of science that we have been taught and take for granted.

Professor Jang Ha-seok said in an interview with domestic media, “Now we use the word ‘electricity’ as a matter of course, but at first it was such an unfamiliar and difficult word.

Let me give you an example.

"Why does static electricity occur? It's because of free electrons. Where do free electrons come from?" he asked.

Professor Jang Ha-seok noted that we use words like electricity and temperature so easily and naturally, but when we ask ourselves what they mean, they feel very unfamiliar and difficult.

Among various common-sense scientific concepts, Professor Jang Ha-seok paid particular attention to 'temperature' and asked a question like that of an eight-year-old: "When measuring temperature using a thermometer, how can we measure the temperature of the thermometer that measures temperature?"

The answer to this seemingly simple question was not immediately apparent.

Professor Jang Ha-seok said in his “Notes on the Publication of the Korean Edition” of the book, “Modern physics does not even address such trivial issues, and epistemological thinking has not yielded any answers.”

So, Professor Jang Ha-seok studied the history of science to understand the foundations of scientific knowledge, and since many important achievements at the time came from France, he even learned French.

Even after researching like this, the answer to the above question did not come easily.

Professor Jang Ha-seok was deeply immersed in temperature and thermometers for a long time, and it took exactly 10 years for him to finally publish “The Philosophy of Thermometers.”

You might ask, “Do you have a thermometer?”

To this question, Professor Jang Ha-seok said this:

“If you delve deep into learning, it’s all like that.”

Resetting the Field of Science: Complementary Science

We tend to think that science is only about studying cutting-edge things.

On the other hand, some people think that solving the problem is based on facts that have already been revealed.

In this book, Professor Jang Ha-seok presents a new method of scientific activity.

Professor Jang Ha-seok argues that true science is a dynamic process of exploring and revising to arrive at the truth, and that it is not a tool for achieving results, but rather a culture.

He views science as a culture and believes that science can provide a transdisciplinary perspective that transcends the limitations of existing academic disciplines by interacting with the humanities, including history and philosophy, and the arts.

This book presents examples of transdisciplinary scientific activities called 'complementary science'.

Complementary science is a discipline that contributes to scientific knowledge through the study of history and philosophy, and asks scientific questions that are excluded from modern professional science.

Professor Jang Ha-seok presented the history and philosophy of science as research methods for complementary science.

“If you learn about the history of science, you will realize that the relationship between science and technology, and science and other disciplines, is constantly changing,” he said in an interview with domestic media. “In ancient times, science was not only considered a part of philosophy, but it was also closely related to medicine, theology, music, etc., so you will be able to understand the various connections between science.”

Reviving the great currents of philosophy and science through the history of science

"The Philosophy of Thermometers" traces the development of various temperature measurement systems before the concept of Celsius used in Korea, Fahrenheit used in the United States, and absolute temperature used by physicists.

It contains the struggle to establish fixed points for the thermometer, such as the boiling point and freezing point, as well as the efforts to establish a numerical thermometer by drawing the thermometer scale after over a century of debate and experimentation.

Next, we discussed the method of measuring temperature at extreme high or low temperatures beyond the range that a mercury thermometer can measure, and the process of its theoretical development.

This series of events was not an easy task and took 200 years.

Think about it for a moment.

To fix a fixed point, we need to know what boiling is, and we need to fix a standard point among the boiling points that fluctuate depending on various factors including pressure.

And unlike the red line in the mercury thermometers we use, thermometers of the past did not expand linearly with temperature.

Also, the thermometers of that time would freeze in extreme cold and melt in hot places such as inside a pottery kiln.

The history of the thermometer was more difficult than we thought, and in the process of overcoming it, great heroes emerged, such as Fahrenheit, famous for the Fahrenheit thermometer, Celsius for the Celsius thermometer, Black who measured latent heat, Irvine who developed the theory of heat capacity, de Luc and Cavendish who fixed the boiling point, Wedgwood, a master of ceramics, and William Thomson who established the modern theory of thermodynamics.

While telling an interesting story about the development of temperature measurement, Professor Jang Ha-seok revealed through a meticulous scientific study of the history of temperature measurement that the process of temperature measurement was a meaningful scientific undertaking that revealed many new phenomena that had not yet been explained.

And he explained philosophically that in the process of determining absolute temperature, it was inevitable to introduce several metaphysical assumptions and conventions.

This showed that scientific theories objectively capture the characteristics of nature, but also reflect the scientific views of the individual scientists who create the theories.

A great achievement representing the 21st century philosophy of science

Professor Jang Ha-seok's research style is similar to that of Thomas Kuhn (1992-1996), who left a significant mark on both the history and philosophy of science.

Thomas Kuhn showed that those who had argued for geocentrism before Copernicus were not simply mistaken or stubborn, but rather supported geocentrism under intense empirical evidence and theoretical conditions.

Professor Jang Ha-seok also shows that even before the invention of the current thermometer, people who created their own thermometers chose and researched temperature measurement methods in an extremely rational manner.

Professor Jang Ha-seok also argues that scientists choose one theory among competing theories by comprehensively considering conflicting empirical evidence and various theoretical conditions, and that even though the vast majority of scientists perform the selection process extremely rationally, they can still have different opinions.

Professor Jang Ha-seok rediscovered the French scientist Victor Regnault and used it as an example to explain his argument.

Although not well known to us today, Regnault was a scholar who held a dominant position in the 19th-century European physics community.

Even William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin), who perfected the concept of absolute temperature, trained in his laboratory and left a tribute to Regnault.

He developed an argument for selecting a fluid for accurate temperature measurement through very precise experiments.

Research on these temperature measurements was quickly and widely accepted in Europe at the time.

His reasoning was impeccable, his technique unparalleled.

The thoroughness of the experimental process was even more evident.

And he skillfully avoided theoretical criticism.

However, the theoretical definition of absolute temperature was established by William Thomson, who had trained in Regnault's laboratory in his youth, and Regnault's research was quickly forgotten.

Just because Renault was overshadowed by Thompson, it doesn't mean his research was meaningless.

Professor Jang Ha-seok, through the history of competing concepts of temperature and the various manipulations (or implementations) to empirically measure it, has re-asked and presented more systematic answers to questions that are considered philosophical in the 'narrow' sense of modern science, but were in fact excellent 'scientific' questions without controversy to scientists of the past.

This is in line with his belief that the history and philosophy of science can be a 'complement' to modern science through 'doing science' in a different sense.

Scientific activity as true integration

Professor Jang Ha-seok concludes his book by arguing that complementary science can trigger a decisive transformation in the nature of our scientific knowledge through this process:

With the expanding and diversifying current body of expert knowledge, we can create more complementary knowledge systems that combine the regeneration of older sciences, new judgments about past and present science, and the exploration of alternatives.

This kind of knowledge will be accessible to non-experts as well.

It may also be useful, or at least interesting, to current experts, as it may show the reasons behind the acceptance of the basic contents of scientific knowledge.

While it may interfere with the research of experts in that it erodes blind faith in fundamentals, I believe it actually produces beneficial effects overall.

3. Structure and Summary of "The Philosophy of the Thermometer"

A science book for both scholars and general readers

Although this book is academic, it can also be of interest to non-specialist readers.

Professor Jang Ha-seok explained in his “Notes on the Publication of the Korean Edition” that he devoured Carl Sagan’s “Cosmos” as a child, and that the book not only fostered his passion for science but also shaped his political and philosophical worldview.

So, like Cosmos, he structured it so that it could be accessible to all readers interested in science, using friendly analogies to explain things and adding various photos, illustrations, and tables to keep readers interested and engaged.

Chapters 1 through 4 cover the history and philosophy of scientific knowledge about temperature, which is now taken for granted.

These chapters are divided into narrative and analytical parts, the historical part covering the development of the thermometer and the subsequent philosophical debates of the time.

The analysis section covers broader philosophical and historical topics than the historical section above, and separates out in-depth discussions that might disrupt the flow of history.

Chapter 5 organizes the previous four chapters into a systematic and explicit philosophical discussion.

Chapter 6 clearly states what the author hopes to achieve through research such as that in this book.

Professor Jang Ha-seok recommended that if you are interested in history, you can read only the history section of the first four chapters, and that you read the analysis section of the four chapters according to your specific interests.

If you find the detailed historical part difficult to endure, you can just read the analysis part of Chapters 1-4 and Chapter 5.

Chapter 6 is primarily intended for professional scholars and students in the philosophy of science, and is recommended for those who are interested in the research presented in the preceding chapters, or who find such research activities perplexing or confusing.

[Summary of each chapter]

Chapter 1: Fixing the Fixed Point of the Thermometer

We rediscover and reacquaint ourselves with the old challenge of finding the fixed point of the thermometer, now forgotten and unrealistic.

History: What to do when water doesn't boil at its boiling point

It contains a historical account of the remarkable challenges scientists faced and overcame as they worked to establish a fixed point: the boiling point of water.

The struggles primarily concerned the task of establishing fixed points for temperature measurement.

Analysis: The Meaning and Achievement of Fixity

We have philosophically examined what it really means for a phenomenon to become a fixed point, and how fixity can be determined if there are no established standards.

We also discuss what implicit standards are employed in the successful construction of anchor points and the cognitive strategies used to defend anchor points and their standards.

In addition, we also looked at the case of freezing points that are different from boiling points.

Chapter 2: Spirits, Air, and Mercury

History: In Search of a 'Real' Scale of Temperature

It contains the scientific efforts to establish a numerical thermometer and the process of resolving philosophical difficulties that were overcome after over a century of debate and experimentation.

Once the anchor points are established at a reasonable level, we describe a procedure for numbering the intervals between the anchor points and the ranks of the columns outside them.

Analysis: Measurement and Theory in the Context of Empiricism

It deals with Regnault, who experimentally and cognitively implemented the most perfect practical thermometry method of his time, and made progress from thermoscope to numerical thermometer.

Renault expanded the scope of observability and responsibly explored the metaphysics of temperature measurement.

Regnault's achievements were the pinnacle of empiricism after Laplace.

Chapter 3: Moving Beyond

History: Measuring Temperatures When a Thermometer Melts and Freezes

It contains the process of extending the scale of a numerical thermometer beyond its established temperature range.

When mercury freezes or boils, the thermometer breaks or melts.

How should the temperature be measured at this time? This section covers how the highest and lowest temperature points are handled.

One is the study of the freezing point of mercury, and the other is the efforts of the master potter Wedgwood to create a thermometer that could measure the temperature of a kiln.

Analysis: Expanding the Concept Beyond Birthplace

We discuss the philosophical justification for extending established knowledge beyond its domain and the key issues surrounding the meaning of such work.

Here, I use a perspective that revives Percy Bridgman's operationalist philosophy to further explain the process by which a concept extends beyond the realm of phenomena it initially describes.

Chapter 4 Theory, Measurement, and Absolute Temperature

History: In search of the theoretical meaning of temperature

Looking at the three previous chapters, we can see that the study of temperature measurement was conducted without a precise theory of temperature or heat.

Until the mid-19th century, most temperature measurements were made without much theoretical understanding.

Chapter 4's historical section shows why the connection between thermometry and heat theory was so difficult, and how that connection was successfully achieved.

This book covers classical thermodynamics, excluding recent thermodynamic theories such as statistical thermodynamics.

Analysis: Operationalization - Creating Contact Between Objects and Actions

Once a theory is developed, its empirical significance must be verified and its verifiability must be examined.

To do this, we need to connect abstract theoretical structures with physical operations.

In this process of connection, meanings that did not exist before are created.

Thomson's absolute temperature can also be said to be a newly born operational meaning. In this section, we look back on the history of Thomson's attempts to measure absolute temperature, examine the operationalizations he performed, and discuss whether these operationalizations were carried out well.

Chapter 5: Measurement, Justification, and the Progress of Science

When we try to justify our measurement methods, we discover the circle inherent in empiricist foundationalism.

The only productive way to deal with such a cycle is to accept it and acknowledge that justification within empirical science cannot but support coherentism.

Within such coherence theory, epistemic repetition becomes an effective way to achieve scientific progress, ultimately enriching and self-correcting the initially identified system.

This way of making scientific progress embraces both conservatism and pluralism.

Chapter 6: Complementary Science—Extended Science in a Different Way: History and Philosophy of Science

We aim to demonstrate that complementary science is a productive direction for the history and philosophy of science.

Complementary science could trigger a decisive transformation in the nature of our scientific knowledge.

In addition to the expanding and diversifying current professional knowledge, we can create more new knowledge systems by reviving old science, making new judgments about past and present science, and exploring alternatives.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of publication: October 25, 2013

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 544 pages | 936g | 153*224*35mm

- ISBN13: 9788962620740

- ISBN10: 896262074X

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)