Feminism Classroom

|

Description

Book Introduction

The Age of Hatred… … Feminism Asks About Teenagers' Well-Being This book is an attempt to understand and seek change in the hateful world we live in through the innovative lens of feminism. Above all, we have tried to capture and share your diverse daily lives and specific concerns. The title is 'Classroom', but what the older generation teaches and the current generation learns unilaterally is not feminism. It is a 'talk to communicate' from the older generation to the current generation. _From 'Entering' "Feminism Classroom" is a feminist textbook that walks into a classroom where hate and profanity are a form of play, and brings to life illustrations of what young people are seeing and experiencing at this very moment. In this age overflowing with hatred toward others, we ask whether young people are well and happy, whether they think things are okay the way they are, and whether there are hidden intentions behind their harsh words and actions. The authors of this book are ten feminists. Kim Go-yeon-ju, a gender advisor for Seoul City and author of “My First Gender Class,” participated as the editor and writer (Chapter 3, “Love and Romance”), and Su-shin Ji, author of “Daughter-in-law,” participated as the illustrator. In addition, Choi Hyun-hee, a teacher at Majungmul (Chapter 1, 'School'), Choi Ji-eun, author of 'It's Not Okay' (Chapter 2, 'Popular Culture'), Tae Hee-won, a researcher at Chungnam Women's Policy Development Institute (Chapter 4, 'Decorated Labor'), Kim Elly, a visiting professor at Myongji University (Chapter 5, 'Military'), Kim Bo-hwa, a senior researcher at the Ullim Research Institute affiliated with the Korea Sexual Violence Relief Center (Chapter 6, 'Me Too Movement', etc.), women's studies researcher Kim Ae-ra (Chapter 7, 'Peer Culture'), human rights activist Na Young-jeong (Chapter 8, 'LGBTI'), and Kim Su-ah, a lecturer at Seoul National University (Chapter 9, 'Online Culture') explain sharp feminist issues in their respective fields from the perspective of young people. This book is not an introductory book introducing the concept and history of feminism. At this very moment, we ask, "Why?" and suggest, "Let's think differently" about the cases that teenagers frequently see and experience at school, among their peers, on smartphones, the internet, and TV. Instead of limiting or beating around the bush, the authors get to the heart of a wide range of issues. It covers feminist issues that anyone living in the present should know, including misogyny and minority hatred that have engulfed the daily lives of teenagers, dating violence that is not unrelated to teenagers, decorative labor and de-corseting, the Me Too movement and School Me Too, the military that has become a fountain of hatred, popular culture that spreads and reinforces sexism, anti-feminism that runs wild online, and ways to deal with sexual violence as a perpetrator, victim, or bystander. This is because we believe that young people are not just objects to be protected or immature beings who do not know anything yet, but rather beings with whom we “live in the present and create the future together.” This book started from regret and concern about reality. The sense of urgency that we cannot leave our youth in the extreme culture represented by Ilbe, and the sense of responsibility as the older generation that created today's reality, are reflected in every page. The authors address the anger, resentment, sadness, and frustration that have taken root in the hearts of young people, and encourage them to navigate this age of hatred together with the power of feminism. It dispels the misandry controversy and claims of reverse discrimination that accompany feminism, and the matador that feminism incites conflict, and tells us what feminism truly aims for. I recommend this book to all generations, including teenagers, young adults, and their parents, as it invites us to embark on an adventure together through the new lens of feminism. The distance between feminism and yourself is up to you. There is no need to be impatient and think, ‘I should become a feminist soon,’ or feel burdened and think, ‘Should I become a feminist?’ You can do whatever you want, however you like. Because your identity is something you create for yourself. And regardless of whether one identifies as a feminist, the goals of feminism, including gender equality, diversity, and human dignity, will be lifelong topics for everyone. Feminism will always be by your side along the way. _Pages 200-201 (Excerpt - Feminist, Who Are You?) |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Entering

Chapter 1.

School: An Adventure Called Feminism (Choi Hyun-hee, Teacher)

Chapter 2.

Popular Culture: Women Disappearing on a Tilt Playground (Ji-eun Choi, author of "It's Not Okay")

Chapter 3.

Love and Romance: Encounters and Partings with Beings Who Are Not Mine (Kim Go-yeon-ju, Seoul City Gender Advisor)

Chapter 4.

The Labor of Decoration: Women Who Live by Adornment, Men Who Don't Wash Their Hands (Tae Hee-won, Researcher, Chungnam Women's Policy Development Institute)

Chapter 5.

Military: Should Women Go to the Military Too? (Kim Ellie, Visiting Professor at Myongji University)

Chapter 6.

The Me Too Movement: You Are Not Alone (Kim Bo-hwa, Senior Researcher at the Ullim Research Center, affiliated with the Korea Sexual Violence Relief Center)

Chapter 7.

Peer Culture: Imagining a Classroom Where Discrimination and Hate Are "Boring" (Kim Ae-ra, Women's Studies Researcher)

Chapter 8. LGBTI: Why We Must Stand Together Against Homophobia (Na Young-jeong, Human Rights Activist)

Chapter 9.

Online Culture: Hate and Violence Ride Online (Kim Soo-ah, Professor, Seoul National University)

Coming out.

Feminist, Who Are You? (Kim Go-yeon-ju, Seoul City Gender Advisor)

supplement.

Q&A: How to Deal with Sexual Violence (Kim Bo-hwa, Senior Researcher at the Ullim Research Institute, affiliated with the Korea Sexual Violence Relief Center)

Chapter 1.

School: An Adventure Called Feminism (Choi Hyun-hee, Teacher)

Chapter 2.

Popular Culture: Women Disappearing on a Tilt Playground (Ji-eun Choi, author of "It's Not Okay")

Chapter 3.

Love and Romance: Encounters and Partings with Beings Who Are Not Mine (Kim Go-yeon-ju, Seoul City Gender Advisor)

Chapter 4.

The Labor of Decoration: Women Who Live by Adornment, Men Who Don't Wash Their Hands (Tae Hee-won, Researcher, Chungnam Women's Policy Development Institute)

Chapter 5.

Military: Should Women Go to the Military Too? (Kim Ellie, Visiting Professor at Myongji University)

Chapter 6.

The Me Too Movement: You Are Not Alone (Kim Bo-hwa, Senior Researcher at the Ullim Research Center, affiliated with the Korea Sexual Violence Relief Center)

Chapter 7.

Peer Culture: Imagining a Classroom Where Discrimination and Hate Are "Boring" (Kim Ae-ra, Women's Studies Researcher)

Chapter 8. LGBTI: Why We Must Stand Together Against Homophobia (Na Young-jeong, Human Rights Activist)

Chapter 9.

Online Culture: Hate and Violence Ride Online (Kim Soo-ah, Professor, Seoul National University)

Coming out.

Feminist, Who Are You? (Kim Go-yeon-ju, Seoul City Gender Advisor)

supplement.

Q&A: How to Deal with Sexual Violence (Kim Bo-hwa, Senior Researcher at the Ullim Research Institute, affiliated with the Korea Sexual Violence Relief Center)

Detailed image

Into the book

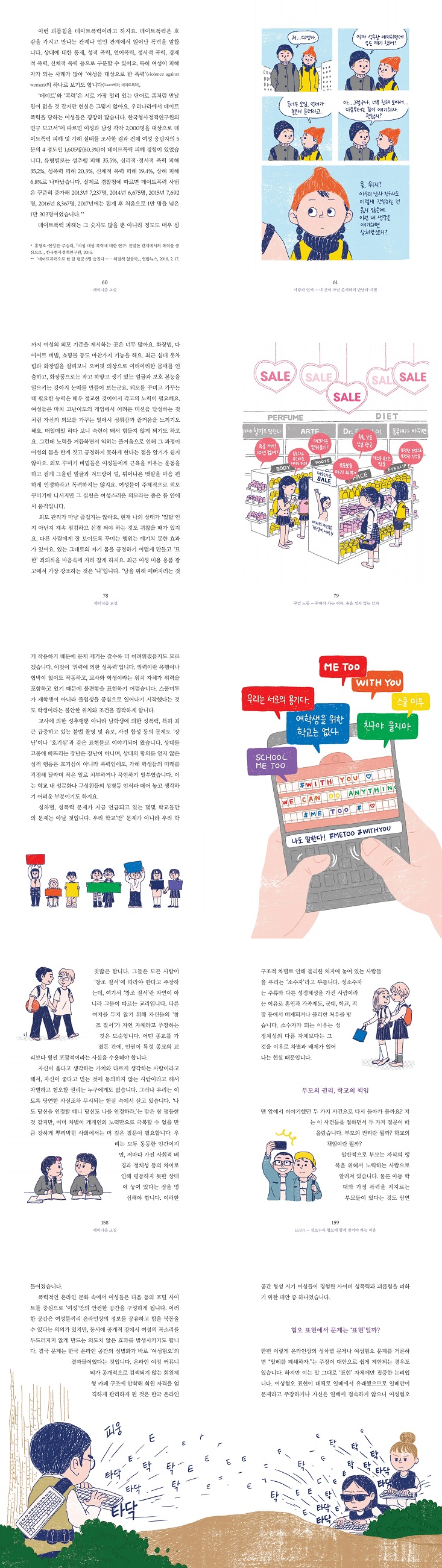

The act of dressing up to look good to others has unexpected effects.

It makes it difficult to accept your body as it is and causes a strange sense of guilt to settle in your mind.

The most emphasized thing in recent women's beauty product advertisements is 'me'.

“I’m not trying to be pretty for others, I’m trying to be pretty for myself.” “I want to be the me that I like more than the me that the world likes.

○○'s 'me' standard." By changing beauty to me, he emphasizes that makeup is my subjective standard and practice.

We place the responsibility for our appearance on women, while leaving the standards for evaluating appearance—shiny hair, poreless, baby-like skin, slim figure—still intact.

All products for skin and hair, all cosmetics, promise to cover up or improve my flaws.

_Pages 78-80 (Chapter 4.

The Labor of Decoration - A Woman Who Lives by Decorating, A Man Who Doesn't Wash His Hands)

When talking about the military, childbirth comes up like a sidekick.

The logic is that if men go to the military, women give birth.

There is also a common argument that if extra points are given to male military personnel, extra points should also be given to mothers.

However, there is no law that requires all men to join the military.

There is no law that says that all women must give birth.

However, such acts were assigned to men and women respectively, and became fixed gender roles.

And it became the basis for explaining what a man is and what a woman is.

In the process, these acts were perceived as 'original'.

In fact, the relationship between military service and childbirth is a socially constructed idea.

The military is organized and operated based on this gender division of labor.

There are quite a few stereotypes here.

So, juxtaposing military service with childbirth only creates bias.

_Pages 95-97 (Chapter 5.

Military - Should women go to the military too?)

Many victims of sexual assault become confused after experiencing the damage, wondering whether it was sexual assault and what to do. They also feel guilty, as if they did something wrong and it was their fault.

In the meantime, they meet the perpetrator again, and exchange messages, sending 'cute' emoticons, in an attempt to pretend that it was not sexual violence.

The identity of a victim of sexual violence may be recognized immediately after the incident, but it is also 'chosen' after deciding to change all the disadvantages, relationships, and positions in relation to those around them, family, work, school, and the investigation/trial process. Therefore, it is reinterpreted not only in the damage done at the time of the incident but also in all areas of life after the damage.

Choosing to become a victim is a complex and difficult task.

Pages 208-209 (Appendix - Q&A, How to Deal with Sexual Violence)

It makes it difficult to accept your body as it is and causes a strange sense of guilt to settle in your mind.

The most emphasized thing in recent women's beauty product advertisements is 'me'.

“I’m not trying to be pretty for others, I’m trying to be pretty for myself.” “I want to be the me that I like more than the me that the world likes.

○○'s 'me' standard." By changing beauty to me, he emphasizes that makeup is my subjective standard and practice.

We place the responsibility for our appearance on women, while leaving the standards for evaluating appearance—shiny hair, poreless, baby-like skin, slim figure—still intact.

All products for skin and hair, all cosmetics, promise to cover up or improve my flaws.

_Pages 78-80 (Chapter 4.

The Labor of Decoration - A Woman Who Lives by Decorating, A Man Who Doesn't Wash His Hands)

When talking about the military, childbirth comes up like a sidekick.

The logic is that if men go to the military, women give birth.

There is also a common argument that if extra points are given to male military personnel, extra points should also be given to mothers.

However, there is no law that requires all men to join the military.

There is no law that says that all women must give birth.

However, such acts were assigned to men and women respectively, and became fixed gender roles.

And it became the basis for explaining what a man is and what a woman is.

In the process, these acts were perceived as 'original'.

In fact, the relationship between military service and childbirth is a socially constructed idea.

The military is organized and operated based on this gender division of labor.

There are quite a few stereotypes here.

So, juxtaposing military service with childbirth only creates bias.

_Pages 95-97 (Chapter 5.

Military - Should women go to the military too?)

Many victims of sexual assault become confused after experiencing the damage, wondering whether it was sexual assault and what to do. They also feel guilty, as if they did something wrong and it was their fault.

In the meantime, they meet the perpetrator again, and exchange messages, sending 'cute' emoticons, in an attempt to pretend that it was not sexual violence.

The identity of a victim of sexual violence may be recognized immediately after the incident, but it is also 'chosen' after deciding to change all the disadvantages, relationships, and positions in relation to those around them, family, work, school, and the investigation/trial process. Therefore, it is reinterpreted not only in the damage done at the time of the incident but also in all areas of life after the damage.

Choosing to become a victim is a complex and difficult task.

Pages 208-209 (Appendix - Q&A, How to Deal with Sexual Violence)

--- From the text

Publisher's Review

Chapter 1.

School: An Adventure Called Feminism Together

The first place that “Feminism Classroom” focuses on is schools.

Teacher Choi Hyun-hee, who was caught up in an unexpected storm after her interview titled "We Need Feminist Teachers," shares her experiences and convictions about what feminism is and why feminist education is necessary.

Feminism is an adventure that "leaves the comfort zone of convention" and "gains a broad perspective and new perspectives" by questioning the "world of the obvious and the natural," and feminist education is "learning how to ask questions" and "practice in looking at the world from the perspective of the weak, not the norm of our society."

Those who cannot imagine the opportunity to experience feminist education or the concrete landscape of the classroom that feminist education will change seem to project vague fears and dread onto feminism.

(……) such as extreme education that hates men, or brainwashing education that is not appropriate for a ‘young’ age.

But feminist education is simply learning how to ask questions.

It is also an exercise in looking at the world from the perspective of the underprivileged, not the norm in our society.

We often question who sets the world's many standards, why they are necessary, and who they are for.

Page 23

Chapter 2.

Pop Culture: Women Disappearing on a Tilt Playground

Ji-eun Choi, who worked as a pop culture reporter and published "It's Not Okay," talks about the misogyny and sexism prevalent in pop culture, focusing on idols, entertainment, and webtoons.

They criticize the controversy over the attitude of following girl groups too well, the double standards that evaluate male and female idols differently, the variety shows that only feature men, from traveling and raising children to feeding dogs, and the problem of webtoons that punish women by presenting 'women who deserve to be hit' or sexually objectify women.

In conclusion, it is said that while discriminatory pop culture content is gaining popularity, as if it is mocking the uselessness of 'pretending to be unnecessarily serious', there are things that need to be considered along with or before fun.

For girl groups, 'expression controversies', 'attitude controversies', and 'personality controversies' occur particularly frequently.

This is not because girl group members commit more mistakes than boy group members, but because the standards we hold them against are wrong.

Was it really wrong to not smile for a moment, to cry after being rudely spoken to, to not wear a bra? Why did posting a photo on social media of myself holding a prop with the phrase "Girls can do anything" and saying I was reading "Kim Ji-young, Born 1982" become a "feminist controversy"? These controversies seem to suggest that in Korea, girl group members must remain completely silent about their emotions and thoughts to avoid criticism.

_Page 32

Chapter 3.

Love and Romance: Encounters and Partings with Beings Who Are Not Mine

Kim Go-yeon-ju, a gender advisor for the Seoul Metropolitan Government and the editor of this book, talks about the changing and evolving nature of love and the seriousness of dating violence, which has led to the emergence of the term "safe breakup."

Throughout the text, the author repeatedly emphasizes that “a romantic relationship cannot be established if one person refuses” and that “the feeling of love and a romantic relationship cannot be forced.”

Introducing the National Police Agency statistics that show that among the 8,985 perpetrators of dating violence from January to August 2018, 286 (3.2%) were teenagers, it points out that the issue of youth dating violence can easily be overlooked in a social culture that does not welcome teenage dating.

Additionally, we introduce self-diagnosis and coping methods for dating violence prepared by the Korea Women's Hotline.

As with any relationship, romantic relationships require mutual understanding to begin and maintain.

If one of you doesn't want to be in a relationship or wants to end it, you can't be in a relationship.

If you want to date that person, or want to continue seeing that person, but the other person rejects you, you will feel many emotions such as sadness, pain, hatred, resentment, and hatred.

But even if I truly love the other person, and I'm confident that they can do really well, and it hurts so much that I feel like I'm going to die because they don't understand my feelings, and I can't understand why they don't accept my feelings, if the other person rejects me, then the two of us can't be lovers.

“You can only be a couple if you both agree.” This is the core of a romantic relationship.

Pages 58-59

Chapter 4.

The Labor of Decoration: A Woman Who Lives by Adornment, a Man Who Doesn't Wash His Hands

Tae Hee-won, a researcher at the Chungnam Women's Policy Development Institute who has focused on the intersection of body care culture, gender, and technology, examines the body trapped in gender stereotypes and the issue of decorative labor, which has recently emerged as a hot issue among young people.

A hot topic on the internet a few years ago (“Do men really not wash their hands after using the bathroom?”) raises the issue of double standards for the body and body care that are applied differently depending on the gender.

In addition, it talks about the limitations of decorative labor that is packaged as a voluntary effort for an independent 'self' but in reality has no choice but to move within the narrow framework of a 'feminine appearance', the sizes of women's clothing that are far from the average body type, school uniforms for girls that are smaller than children's clothing for 7-8 year olds, and the rise of the de-corset movement that rejects the system that evaluates femininity.

Women often find a sense of accomplishment and pleasure in cultivating their appearance, as if they were completing a difficult mission in a high-difficulty game.

If you do it every day, you will become more skilled at it and it will not be difficult.

But it's not easy to see that the joy of learning through repeated effort can limit and deny a woman's body.

Beauty tips don't encourage women to exercise to build muscle and to embrace their tanned faces, hairy underarms, and protruding bellies.

Although women take the initiative in shaping their appearance, their actions are carried out within the narrow framework of a feminine appearance.

Page 78

Chapter 5.

Military: Should women also serve in the military?

Kim Eli, a visiting professor at Myongji University who teaches women's studies and peace studies, shares a story that could spark discussion in the noisy and sluggish debate surrounding the military.

Whenever the issue of gender discrimination is pointed out, the refrain that comes out like a song is “Women should join the military too” and “If you feel wronged, join the military”. In fact, it is a demand for recognition that women should recognize the sacrifices made by men. It is also pointed out that women joining the military does not directly lead to equality, and the logic of pairing military service with childbirth only produces prejudice.

What's really important, he says, is changing the military culture that destroys dignity and discriminates against female soldiers and minorities to be "equal, queer, and diverse."

In the face of the uproar over 'women should also go to the military', the debate structure of 'go vs. not go' is not that relevant.

Just because women enter the military doesn't mean they'll be equal.

Rather, a more democratic and gender-equal society can create a gender-equal military.

So, civil society must create a culture of gender equality and have a positive influence on the military.

Let's think about it a little differently. Can't we create a military culture where soldiers are respected? Equal, queer, and diverse.

Is there a way to strengthen the security of our citizens without pointing a gun at someone's chest? Can we create a military that can resolve conflicts without killing or violence? _Pages 106-107

Chapter 6.

Me Too Movement: You Are Not Alone

Kim Bo-hwa, a senior researcher at the Korea Sexual Violence Relief Center's Ullim Research Center, discusses how the MeToo movement began, its relationship to us, and what sexual violence is.

It explains why common beliefs such as that sexual violence occurs due to a man's uncontrollable sexual desire or a woman's provocative clothing, that rape can be avoided if the victim resists strongly, or that sexual violence cannot occur in intimate relationships are wrong, and also touches on the meaning and possibility of School Me Too, which was imprinted in the memory of the memorable scene of Yonghwa Girls' High School's "Window Me Too."

The issues of gender discrimination and sexual violence are not limited to the few schools that are currently being discussed.

It's not just our school that's the problem, it's our school that's the problem.

Sexist textbooks, different dress codes for girls and boys, questions about the unequal lives of mothers and fathers, different expectations and roles given to younger siblings and themselves, and fears about illegal filming and the streets at night are so embedded and passed down that they have become a natural part of everyday life, making School Me Too not just a school problem.

It is a fierce resistance and challenge from the parties concerned against the overall sexual culture of unequal Korean society.

Pages 122-124

Chapter 7.

Peer Culture: Imagining a Classroom Where Discrimination and Hate Are "Boring"

Kim Ae-ra, a feminist researcher who has focused on youth, especially teenage girls, examines the phenomenon of hatred, discrimination, and profanity becoming commonplace among teenagers, and seeks a way out of this discriminatory and violent peer culture.

It talks about the male peer culture that perceives hate speech and sexual violence as fun play or 'too much pranks', female students who are increasingly becoming like male students out of an intention to protect themselves, and the perception of equality and human rights that differs significantly by gender even within this trend (17.2% of female students and 61.1% of male students have experience using derogatory expressions or padrip toward sexual minorities).

Furthermore, he says that only when I listen to the voices opposing discrimination will my story be heard by others when I am discriminated against.

Violent peer culture is increasingly affecting not only some boys but also the entire peer group, including girls.

For example, female students, in an attempt to protect themselves from a sexist peer culture, began to mimic male student culture by speaking more forcefully, using negative language that brings up minorities, and feminizing others to gain the upper hand.

Interestingly, however, even within this mainstream trend, significant differences in perceptions of equality and human rights are revealed between female and male students.

In a survey asking whether they had ever used derogatory or offensive language toward sexual minorities, 39.6% of all students, 17.2% of female students, and 61.1% of male students responded that they had used such language.

The gender gap is very large.

That is, male students were found to have three times more experience using it than female students.

Page 141

Chapter 8. LGBTI: Why We Must Stand Together Against Homophobia

Na Young-jung, who has been involved in the human rights movements for sexual minorities, women with disabilities, and HIV/AIDS, talks about why we must fight against homophobia along with feminism.

Introducing the cases of Yeonhee, who suffered violence from her parents and church in the name of treating her transgender identity, and Kim, a high school freshman who took his own life after being bullied for being feminine, the author argues that sexual minority identity is not an abnormality that needs to be criticized or corrected, but rather a natural phenomenon that converges with diversity.

It also traces the history of how homosexuality and transgender identity were removed from the International Classification of Diseases and their definitions were redefined through the efforts of sexual minority human rights activists and experts.

Violence doesn't just mean physical violence or sexual assault.

Bullying or ostracizing sexual minorities, or forcing them to reveal their sexual identity, is also violence.

The same goes for criticizing sexual minorities as abnormal, forcing them to change their sexual identity, and preventing them from revealing or expressing their sexual identity.

Why is it violence to prevent expression? Some ask, "If sexual minorities hide their identities, they avoid discrimination and violence, and others feel less uncomfortable, so isn't it a win-win situation?"

But this question itself contains discrimination and violence.

So, let's ask this question: Why don't heterosexuals make others uncomfortable? (pp. 153-154)

Chapter 9.

Online Culture: Hate and Violence Ride Online

Kim Soo-ah, a professor at Seoul National University's Institute of Basic Education who studies popular culture and feminism, traces the process by which misogyny arose and grew online, going back to the era of PC communication.

As the Korea Press Foundation's report (May 2018) shows, 36.4% of men and 23.7% of women write news comments, the online world, like the real world, is an "uneven playing field," and this result is said to be deeply related to the misogynistic emotional structure of the online world.

Furthermore, I suggest that we take a calm and serious look at this again and examine it to prevent the spread of hate online.

Rather than giving up on the potential of a public forum simply by looking at the current state of online spaces, it may be necessary to constantly consider how they can be transformed.

First, why not examine the online content you browse every day to see if any problematic expressions of violence against women or of socially vulnerable and minority groups are being dressed up as humor? If you encounter conflicting content on gender discrimination, why not calmly reexamine which narrative has more basis and the true meaning of discrimination? German political theorist Hannah Arendt observed that where thinking ceases, violence is reiterated without reflection.

What we need now is to take a serious look at it.

Page 182

Coming out.

Feminist, who are you?

Kim Go-yeon recalls the 2015 incident of Kim, who disappeared in Turkey after leaving behind the message, “I hate feminists, so I like ISIS,” and opens up about the misunderstandings surrounding feminism.

Even the National Institute of the Korean Language's Standard Korean Dictionary, which represents the country, lacks consideration of feminism.

At the time of the Kim Gun incident, the National Institute of the Korean Language had been absurdly explaining 'feminist' as 'a person who worships women or a man who is kind to women'. After receiving a strong request from the Korean Women's Association United, the Institute again gave an absurd interpretation, saying, 'In the past, it was a metaphorical term for a man who was kind to women.'

In this way, feminism is still mired in misunderstandings and speculation, and has recently come under even more fierce attacks from anti-feminist forces.

The author says that feminism has now become an irreversible wave, despite this.

Korean society has changed so much that those who are ignorant of feminism or lack sensitivity will inevitably be eliminated.

Furthermore, the author defines feminism not as propagating misandry or inciting conflict, but as “starting from the awareness of the reality of women, a representative social and historical minority, expanding to all people’s minority status, and advocating for equality and dignity for all people through respect for diversity.”

Some people distance themselves from feminism, some ardently support it, and many others are confused about what stance to take.

There is a very wide spectrum of positions and opinions on feminism.

But regardless of where you stand, feminism has now become an unstoppable wave.

No matter what you think about feminism, no one can deny that Korean society has changed to the point where those who are unaware of feminism or lack sensitivity to it will inevitably be eliminated.

Feminism is not just a theory; it's a practice that seeks to change everyday life. Therefore, there are active movements to create gender-equal relationships and cultures everywhere, including at home, school, and the workplace.

Women concerned about dating violence and safety breakups are deciding whether to date or not based on how their partner reacts to feminism.

Pages 193-194

supplement.

Q&A: How to Deal with Sexual Violence

Kim Bo-hwa, a senior researcher at the Ullim Research Institute affiliated with the Korea Sexual Violence Relief Center, said, “Chapter 6.

Following “MeToo Movement: You Are Not Alone,” the appendix provides step-by-step instructions on how to deal with sexual violence in four situations where “I or a friend” becomes the “perpetrator or victim.”

At the beginning of the article, the author asserts that there is no way for victims to prevent sexual violence, and that perpetrators should not perpetrate it.

Furthermore, it shatters prejudices and misunderstandings, such as the idea that sexual violence is committed by "heinous monsters," that the damage caused by sexual violence is an "indelible wound" or "an irreparable scar," or that victims of sexual violence are always depressed and in pain, and tells practical yet moving stories about sexual violence that everyone should keep in mind.

One thing to remember about sexual violence prevention is that there is “no way” for victims to prevent it.

Sexual violence occurs even if you don't walk at night or wear revealing clothes.

So, separating safe and dangerous spaces is not a fundamental prevention.

Since most sexual violence against youth occurs in very close relationships, such as with school friends, seniors, or family, preventing sexual violence is not something that can be done, but rather, it is only possible if the perpetrators do not commit the crime.

Page 202

School: An Adventure Called Feminism Together

The first place that “Feminism Classroom” focuses on is schools.

Teacher Choi Hyun-hee, who was caught up in an unexpected storm after her interview titled "We Need Feminist Teachers," shares her experiences and convictions about what feminism is and why feminist education is necessary.

Feminism is an adventure that "leaves the comfort zone of convention" and "gains a broad perspective and new perspectives" by questioning the "world of the obvious and the natural," and feminist education is "learning how to ask questions" and "practice in looking at the world from the perspective of the weak, not the norm of our society."

Those who cannot imagine the opportunity to experience feminist education or the concrete landscape of the classroom that feminist education will change seem to project vague fears and dread onto feminism.

(……) such as extreme education that hates men, or brainwashing education that is not appropriate for a ‘young’ age.

But feminist education is simply learning how to ask questions.

It is also an exercise in looking at the world from the perspective of the underprivileged, not the norm in our society.

We often question who sets the world's many standards, why they are necessary, and who they are for.

Page 23

Chapter 2.

Pop Culture: Women Disappearing on a Tilt Playground

Ji-eun Choi, who worked as a pop culture reporter and published "It's Not Okay," talks about the misogyny and sexism prevalent in pop culture, focusing on idols, entertainment, and webtoons.

They criticize the controversy over the attitude of following girl groups too well, the double standards that evaluate male and female idols differently, the variety shows that only feature men, from traveling and raising children to feeding dogs, and the problem of webtoons that punish women by presenting 'women who deserve to be hit' or sexually objectify women.

In conclusion, it is said that while discriminatory pop culture content is gaining popularity, as if it is mocking the uselessness of 'pretending to be unnecessarily serious', there are things that need to be considered along with or before fun.

For girl groups, 'expression controversies', 'attitude controversies', and 'personality controversies' occur particularly frequently.

This is not because girl group members commit more mistakes than boy group members, but because the standards we hold them against are wrong.

Was it really wrong to not smile for a moment, to cry after being rudely spoken to, to not wear a bra? Why did posting a photo on social media of myself holding a prop with the phrase "Girls can do anything" and saying I was reading "Kim Ji-young, Born 1982" become a "feminist controversy"? These controversies seem to suggest that in Korea, girl group members must remain completely silent about their emotions and thoughts to avoid criticism.

_Page 32

Chapter 3.

Love and Romance: Encounters and Partings with Beings Who Are Not Mine

Kim Go-yeon-ju, a gender advisor for the Seoul Metropolitan Government and the editor of this book, talks about the changing and evolving nature of love and the seriousness of dating violence, which has led to the emergence of the term "safe breakup."

Throughout the text, the author repeatedly emphasizes that “a romantic relationship cannot be established if one person refuses” and that “the feeling of love and a romantic relationship cannot be forced.”

Introducing the National Police Agency statistics that show that among the 8,985 perpetrators of dating violence from January to August 2018, 286 (3.2%) were teenagers, it points out that the issue of youth dating violence can easily be overlooked in a social culture that does not welcome teenage dating.

Additionally, we introduce self-diagnosis and coping methods for dating violence prepared by the Korea Women's Hotline.

As with any relationship, romantic relationships require mutual understanding to begin and maintain.

If one of you doesn't want to be in a relationship or wants to end it, you can't be in a relationship.

If you want to date that person, or want to continue seeing that person, but the other person rejects you, you will feel many emotions such as sadness, pain, hatred, resentment, and hatred.

But even if I truly love the other person, and I'm confident that they can do really well, and it hurts so much that I feel like I'm going to die because they don't understand my feelings, and I can't understand why they don't accept my feelings, if the other person rejects me, then the two of us can't be lovers.

“You can only be a couple if you both agree.” This is the core of a romantic relationship.

Pages 58-59

Chapter 4.

The Labor of Decoration: A Woman Who Lives by Adornment, a Man Who Doesn't Wash His Hands

Tae Hee-won, a researcher at the Chungnam Women's Policy Development Institute who has focused on the intersection of body care culture, gender, and technology, examines the body trapped in gender stereotypes and the issue of decorative labor, which has recently emerged as a hot issue among young people.

A hot topic on the internet a few years ago (“Do men really not wash their hands after using the bathroom?”) raises the issue of double standards for the body and body care that are applied differently depending on the gender.

In addition, it talks about the limitations of decorative labor that is packaged as a voluntary effort for an independent 'self' but in reality has no choice but to move within the narrow framework of a 'feminine appearance', the sizes of women's clothing that are far from the average body type, school uniforms for girls that are smaller than children's clothing for 7-8 year olds, and the rise of the de-corset movement that rejects the system that evaluates femininity.

Women often find a sense of accomplishment and pleasure in cultivating their appearance, as if they were completing a difficult mission in a high-difficulty game.

If you do it every day, you will become more skilled at it and it will not be difficult.

But it's not easy to see that the joy of learning through repeated effort can limit and deny a woman's body.

Beauty tips don't encourage women to exercise to build muscle and to embrace their tanned faces, hairy underarms, and protruding bellies.

Although women take the initiative in shaping their appearance, their actions are carried out within the narrow framework of a feminine appearance.

Page 78

Chapter 5.

Military: Should women also serve in the military?

Kim Eli, a visiting professor at Myongji University who teaches women's studies and peace studies, shares a story that could spark discussion in the noisy and sluggish debate surrounding the military.

Whenever the issue of gender discrimination is pointed out, the refrain that comes out like a song is “Women should join the military too” and “If you feel wronged, join the military”. In fact, it is a demand for recognition that women should recognize the sacrifices made by men. It is also pointed out that women joining the military does not directly lead to equality, and the logic of pairing military service with childbirth only produces prejudice.

What's really important, he says, is changing the military culture that destroys dignity and discriminates against female soldiers and minorities to be "equal, queer, and diverse."

In the face of the uproar over 'women should also go to the military', the debate structure of 'go vs. not go' is not that relevant.

Just because women enter the military doesn't mean they'll be equal.

Rather, a more democratic and gender-equal society can create a gender-equal military.

So, civil society must create a culture of gender equality and have a positive influence on the military.

Let's think about it a little differently. Can't we create a military culture where soldiers are respected? Equal, queer, and diverse.

Is there a way to strengthen the security of our citizens without pointing a gun at someone's chest? Can we create a military that can resolve conflicts without killing or violence? _Pages 106-107

Chapter 6.

Me Too Movement: You Are Not Alone

Kim Bo-hwa, a senior researcher at the Korea Sexual Violence Relief Center's Ullim Research Center, discusses how the MeToo movement began, its relationship to us, and what sexual violence is.

It explains why common beliefs such as that sexual violence occurs due to a man's uncontrollable sexual desire or a woman's provocative clothing, that rape can be avoided if the victim resists strongly, or that sexual violence cannot occur in intimate relationships are wrong, and also touches on the meaning and possibility of School Me Too, which was imprinted in the memory of the memorable scene of Yonghwa Girls' High School's "Window Me Too."

The issues of gender discrimination and sexual violence are not limited to the few schools that are currently being discussed.

It's not just our school that's the problem, it's our school that's the problem.

Sexist textbooks, different dress codes for girls and boys, questions about the unequal lives of mothers and fathers, different expectations and roles given to younger siblings and themselves, and fears about illegal filming and the streets at night are so embedded and passed down that they have become a natural part of everyday life, making School Me Too not just a school problem.

It is a fierce resistance and challenge from the parties concerned against the overall sexual culture of unequal Korean society.

Pages 122-124

Chapter 7.

Peer Culture: Imagining a Classroom Where Discrimination and Hate Are "Boring"

Kim Ae-ra, a feminist researcher who has focused on youth, especially teenage girls, examines the phenomenon of hatred, discrimination, and profanity becoming commonplace among teenagers, and seeks a way out of this discriminatory and violent peer culture.

It talks about the male peer culture that perceives hate speech and sexual violence as fun play or 'too much pranks', female students who are increasingly becoming like male students out of an intention to protect themselves, and the perception of equality and human rights that differs significantly by gender even within this trend (17.2% of female students and 61.1% of male students have experience using derogatory expressions or padrip toward sexual minorities).

Furthermore, he says that only when I listen to the voices opposing discrimination will my story be heard by others when I am discriminated against.

Violent peer culture is increasingly affecting not only some boys but also the entire peer group, including girls.

For example, female students, in an attempt to protect themselves from a sexist peer culture, began to mimic male student culture by speaking more forcefully, using negative language that brings up minorities, and feminizing others to gain the upper hand.

Interestingly, however, even within this mainstream trend, significant differences in perceptions of equality and human rights are revealed between female and male students.

In a survey asking whether they had ever used derogatory or offensive language toward sexual minorities, 39.6% of all students, 17.2% of female students, and 61.1% of male students responded that they had used such language.

The gender gap is very large.

That is, male students were found to have three times more experience using it than female students.

Page 141

Chapter 8. LGBTI: Why We Must Stand Together Against Homophobia

Na Young-jung, who has been involved in the human rights movements for sexual minorities, women with disabilities, and HIV/AIDS, talks about why we must fight against homophobia along with feminism.

Introducing the cases of Yeonhee, who suffered violence from her parents and church in the name of treating her transgender identity, and Kim, a high school freshman who took his own life after being bullied for being feminine, the author argues that sexual minority identity is not an abnormality that needs to be criticized or corrected, but rather a natural phenomenon that converges with diversity.

It also traces the history of how homosexuality and transgender identity were removed from the International Classification of Diseases and their definitions were redefined through the efforts of sexual minority human rights activists and experts.

Violence doesn't just mean physical violence or sexual assault.

Bullying or ostracizing sexual minorities, or forcing them to reveal their sexual identity, is also violence.

The same goes for criticizing sexual minorities as abnormal, forcing them to change their sexual identity, and preventing them from revealing or expressing their sexual identity.

Why is it violence to prevent expression? Some ask, "If sexual minorities hide their identities, they avoid discrimination and violence, and others feel less uncomfortable, so isn't it a win-win situation?"

But this question itself contains discrimination and violence.

So, let's ask this question: Why don't heterosexuals make others uncomfortable? (pp. 153-154)

Chapter 9.

Online Culture: Hate and Violence Ride Online

Kim Soo-ah, a professor at Seoul National University's Institute of Basic Education who studies popular culture and feminism, traces the process by which misogyny arose and grew online, going back to the era of PC communication.

As the Korea Press Foundation's report (May 2018) shows, 36.4% of men and 23.7% of women write news comments, the online world, like the real world, is an "uneven playing field," and this result is said to be deeply related to the misogynistic emotional structure of the online world.

Furthermore, I suggest that we take a calm and serious look at this again and examine it to prevent the spread of hate online.

Rather than giving up on the potential of a public forum simply by looking at the current state of online spaces, it may be necessary to constantly consider how they can be transformed.

First, why not examine the online content you browse every day to see if any problematic expressions of violence against women or of socially vulnerable and minority groups are being dressed up as humor? If you encounter conflicting content on gender discrimination, why not calmly reexamine which narrative has more basis and the true meaning of discrimination? German political theorist Hannah Arendt observed that where thinking ceases, violence is reiterated without reflection.

What we need now is to take a serious look at it.

Page 182

Coming out.

Feminist, who are you?

Kim Go-yeon recalls the 2015 incident of Kim, who disappeared in Turkey after leaving behind the message, “I hate feminists, so I like ISIS,” and opens up about the misunderstandings surrounding feminism.

Even the National Institute of the Korean Language's Standard Korean Dictionary, which represents the country, lacks consideration of feminism.

At the time of the Kim Gun incident, the National Institute of the Korean Language had been absurdly explaining 'feminist' as 'a person who worships women or a man who is kind to women'. After receiving a strong request from the Korean Women's Association United, the Institute again gave an absurd interpretation, saying, 'In the past, it was a metaphorical term for a man who was kind to women.'

In this way, feminism is still mired in misunderstandings and speculation, and has recently come under even more fierce attacks from anti-feminist forces.

The author says that feminism has now become an irreversible wave, despite this.

Korean society has changed so much that those who are ignorant of feminism or lack sensitivity will inevitably be eliminated.

Furthermore, the author defines feminism not as propagating misandry or inciting conflict, but as “starting from the awareness of the reality of women, a representative social and historical minority, expanding to all people’s minority status, and advocating for equality and dignity for all people through respect for diversity.”

Some people distance themselves from feminism, some ardently support it, and many others are confused about what stance to take.

There is a very wide spectrum of positions and opinions on feminism.

But regardless of where you stand, feminism has now become an unstoppable wave.

No matter what you think about feminism, no one can deny that Korean society has changed to the point where those who are unaware of feminism or lack sensitivity to it will inevitably be eliminated.

Feminism is not just a theory; it's a practice that seeks to change everyday life. Therefore, there are active movements to create gender-equal relationships and cultures everywhere, including at home, school, and the workplace.

Women concerned about dating violence and safety breakups are deciding whether to date or not based on how their partner reacts to feminism.

Pages 193-194

supplement.

Q&A: How to Deal with Sexual Violence

Kim Bo-hwa, a senior researcher at the Ullim Research Institute affiliated with the Korea Sexual Violence Relief Center, said, “Chapter 6.

Following “MeToo Movement: You Are Not Alone,” the appendix provides step-by-step instructions on how to deal with sexual violence in four situations where “I or a friend” becomes the “perpetrator or victim.”

At the beginning of the article, the author asserts that there is no way for victims to prevent sexual violence, and that perpetrators should not perpetrate it.

Furthermore, it shatters prejudices and misunderstandings, such as the idea that sexual violence is committed by "heinous monsters," that the damage caused by sexual violence is an "indelible wound" or "an irreparable scar," or that victims of sexual violence are always depressed and in pain, and tells practical yet moving stories about sexual violence that everyone should keep in mind.

One thing to remember about sexual violence prevention is that there is “no way” for victims to prevent it.

Sexual violence occurs even if you don't walk at night or wear revealing clothes.

So, separating safe and dangerous spaces is not a fundamental prevention.

Since most sexual violence against youth occurs in very close relationships, such as with school friends, seniors, or family, preventing sexual violence is not something that can be done, but rather, it is only possible if the perpetrators do not commit the crime.

Page 202

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: March 29, 2019

- Page count, weight, size: 212 pages | 403g | 142*200*20mm

- ISBN13: 9788971999301

- ISBN10: 8971999306

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)