Rereading the World History of Capitalism Through Geography

|

Description

Book Introduction

Where is the world economy headed now?

How capitalism arose and evolved,

A three-dimensional view from a geographical perspective!

· The first stocks came from the Dutch herring fishery?

· Why did the splendid metropolis become the epicenter of polarized inequality?

· How did the United States change world hegemony with the transcontinental railroad?

· How did Vietnam become a black hole for the climate crisis?

· Is the future of Korean neoliberalism truly rosy?

In January 2025, Donald Trump's second term in the United States begins.

President-elect Trump has threatened a tariff bombshell on the world, including Europe.

With this as the starting point, as the world worries about a silent trade war, it is expected that Trumpflation (inflation caused by the Trump administration's economic policies) will raise its head again.

Moreover, our country's average won-dollar exchange rate is following the trend during the IMF crisis, bringing back memories of that nightmare.

The reason we pay close attention to economic news and closely monitor political situations in other countries is because we are deeply involved in and are unknowingly influenced by the capitalist environment, including prices, interest rates, exchange rates, and the economy.

You will also feel a sense of crisis that you cannot navigate this harsh world without understanding capitalism.

In his previous work, "Rereading World History through Climate," Professor Lee Dong-min, who provided insight into the climate crisis era through the unique perspective of a geographer, now examines the history of capitalism through "Rereading World History of Capitalism through Geography," drawing on "geographic literacy."

In particular, it comprehensively examines the history of capitalism from a multi-scale approach (a geographical perspective that seeks to understand various phenomena occurring in surface space from a multi-layered and interrelated focus at various scales) that has recently attracted attention in the field of geography.

Reading this book, you can see at a glance how capitalism has moved and changed the world.

During the Age of Exploration, almost all the world's wealth went to Spain, but it soon moved to the Netherlands, and in less than a century, Britain, which had been a remote island nation, emerged as a new economic power.

However, the British Empire, which was called the 'empire on which the sun never sets' and had numerous colonies around the world, lost its position to the United States after two world wars.

A once-dominated country is not a permanent dominion.

How is it now?

The United States, once a superpower during the Cold War, is now facing challenges from China and several European countries that want to recapture their past glory.

Although Russia may have shrunk geographically compared to the past, it is expanding its political influence by exerting pressure on European societies with its natural gas and food resources.

By understanding where the center of the world economy has shifted and why, we can naturally predict the next direction of economic hegemony.

The author points out that this history is intertwined with the course of capitalism, which has repeatedly transformed from commercial capitalism to industrial capitalism, and from modified capitalism to neoliberalism, and that this system, which continues to grow on the surface but expands and reproduces multi-scale inequality, ultimately threatens the sustainability of the global economy and environment.

Without a geopolitical understanding of the multi-scalar nature of today's neoliberal globalization, any hope of fair distribution or moral justice to overcome these ills will remain an empty ideal.

I hope this book will provide readers living in a capitalist society with meaningful insights into how to view not only the flow of economics and wealth, but also the world's geographical order.

How capitalism arose and evolved,

A three-dimensional view from a geographical perspective!

· The first stocks came from the Dutch herring fishery?

· Why did the splendid metropolis become the epicenter of polarized inequality?

· How did the United States change world hegemony with the transcontinental railroad?

· How did Vietnam become a black hole for the climate crisis?

· Is the future of Korean neoliberalism truly rosy?

In January 2025, Donald Trump's second term in the United States begins.

President-elect Trump has threatened a tariff bombshell on the world, including Europe.

With this as the starting point, as the world worries about a silent trade war, it is expected that Trumpflation (inflation caused by the Trump administration's economic policies) will raise its head again.

Moreover, our country's average won-dollar exchange rate is following the trend during the IMF crisis, bringing back memories of that nightmare.

The reason we pay close attention to economic news and closely monitor political situations in other countries is because we are deeply involved in and are unknowingly influenced by the capitalist environment, including prices, interest rates, exchange rates, and the economy.

You will also feel a sense of crisis that you cannot navigate this harsh world without understanding capitalism.

In his previous work, "Rereading World History through Climate," Professor Lee Dong-min, who provided insight into the climate crisis era through the unique perspective of a geographer, now examines the history of capitalism through "Rereading World History of Capitalism through Geography," drawing on "geographic literacy."

In particular, it comprehensively examines the history of capitalism from a multi-scale approach (a geographical perspective that seeks to understand various phenomena occurring in surface space from a multi-layered and interrelated focus at various scales) that has recently attracted attention in the field of geography.

Reading this book, you can see at a glance how capitalism has moved and changed the world.

During the Age of Exploration, almost all the world's wealth went to Spain, but it soon moved to the Netherlands, and in less than a century, Britain, which had been a remote island nation, emerged as a new economic power.

However, the British Empire, which was called the 'empire on which the sun never sets' and had numerous colonies around the world, lost its position to the United States after two world wars.

A once-dominated country is not a permanent dominion.

How is it now?

The United States, once a superpower during the Cold War, is now facing challenges from China and several European countries that want to recapture their past glory.

Although Russia may have shrunk geographically compared to the past, it is expanding its political influence by exerting pressure on European societies with its natural gas and food resources.

By understanding where the center of the world economy has shifted and why, we can naturally predict the next direction of economic hegemony.

The author points out that this history is intertwined with the course of capitalism, which has repeatedly transformed from commercial capitalism to industrial capitalism, and from modified capitalism to neoliberalism, and that this system, which continues to grow on the surface but expands and reproduces multi-scale inequality, ultimately threatens the sustainability of the global economy and environment.

Without a geopolitical understanding of the multi-scalar nature of today's neoliberal globalization, any hope of fair distribution or moral justice to overcome these ills will remain an empty ideal.

I hope this book will provide readers living in a capitalist society with meaningful insights into how to view not only the flow of economics and wealth, but also the world's geographical order.

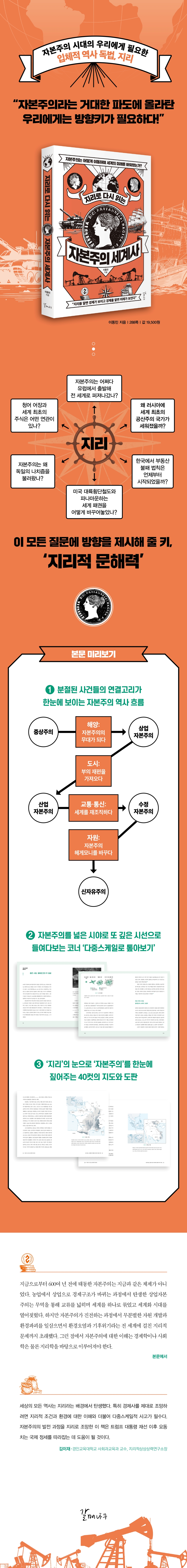

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Introduction: Where did capitalism come from and where is it going? · 4

1.

Capitalism began with maps, compasses, and gunpowder.

Chapter 1: Spain, the first country to cross the Atlantic

Why Did the Iberian Peninsula Turn Its Back on the Continent? · 19

The Tremendous Wealth of Unexpected Resources · 24

Silver, the pioneering reserve currency that ushered in globalization · 26

Spain's Wings Become Asia's Typhoon · 33

Chapter 2: The Netherlands: The Winds of Credit Economy Blowing from the Far Sea

The Restructuring of Wealth by Herring and Storm Surge · 39

Why did Dutch merchants go out to sea? · 44

The birth of the world's first stock exchange · 47

The Birth of Credit: Debt Becomes Assets · 52

Chapter 3 Britain: The Island Power That Led the Financial Revolution to the Industrial Revolution

Gaining Maritime Trade Hegemony through Tax Reform · 63

The Seven Years' War: The Final Piece of the Financial Revolution · 69

The Triangle of the Industrial Revolution: Cotton, Iron Ore, and Coal · 71

Chapter 4: The Freedom of Capital Spread by the French Revolution in the Great Plains

A land blessed with natural conditions · 81

The Bourgeoisie That Grew Along with Commercial Capitalism · 85

The Little Ice Age Explodes the Contradictions of the Class System · 90

What "Freedom" in the Market Means After the Great Revolution · 94

A Time to Explore Multi-Scale: The Two Faces of the Belle Époque · 98

2.

The Earth Divided by the Spread of Anti-Capitalism

Chapter 5: The Specter of Communism That Split Russia and Europe in Half

Half-Capitalism Trapped in a Frozen Sea · 118

Was the Great Game a failure of expansionism? · 123

The Limits of Top-Down Reform, Leading to the World's First Communist State · 130

Chapter 6: Germany: The Tragedy of a Latecomer Capitalist Country That Became the Tinder for Fascism

From Division to Unity, the Birth of a Unified Empire · 141

The Battle for "Lebensraum" Plunges the World into War · 147

The Monster's Run: A Mix of Anti-Communism and Capitalism · 153

What do the fascism that swept through Italy, Germany, and Japan have in common? · 157

Chapter 7: The United States: A New Capitalist Power from the Atlantic to the Pacific

Why did Americans throw crates of tea into the ocean? · 165

A Great River that Connects the Divided Territories · 169

Connecting the East and West with the Transcontinental Railroad, and the North and South with the Panama Canal · 173

The Roaring Twenties: The Great Depression That Destroyed the Great Powers · 182

A Multi-Scale Look: The Growing Scale of War with Capitalism · 185

3.

A new world map drawn by capitalism in Wonderland

Chapter 8: China: The Grand Picture of the "One Belt, One Road" Initiative, Spanning Continents and Oceans

The Cultural Revolution: The Worst Madness in History · 209

The Rise of a Great Power, Reborn as the World's Factory · 213

A Modern Silk Road Linking Eurasia and the Indian Ocean · 216

Where's the 21st-century Great Game? · 222

Chapter 9: Vietnam's Natural Geographical Resources Become a Double-Edged Sword

Is a favorable location a crisis or an opportunity? · 229

Climbing the Precarious Ladder of the Global Value Chain · 232

Doi Moi: A Black Hole of Inequality and Climate Crisis · 236

Chapter 10: The Fate of Korea's Neoliberalism Built on Construction

The "Miracle on the Han River": A Multi-Scale Cold War Experience · 243

The Roots of the Myth of Real Estate's Invincibility · 248

Is Korea's Neoliberalism Really a Rosy Future? · 253

A Multi-Scale Look: Why Neoliberalism Repeats Booms and Recessions · 258

Is there a future for the global economy? · 270

1.

Capitalism began with maps, compasses, and gunpowder.

Chapter 1: Spain, the first country to cross the Atlantic

Why Did the Iberian Peninsula Turn Its Back on the Continent? · 19

The Tremendous Wealth of Unexpected Resources · 24

Silver, the pioneering reserve currency that ushered in globalization · 26

Spain's Wings Become Asia's Typhoon · 33

Chapter 2: The Netherlands: The Winds of Credit Economy Blowing from the Far Sea

The Restructuring of Wealth by Herring and Storm Surge · 39

Why did Dutch merchants go out to sea? · 44

The birth of the world's first stock exchange · 47

The Birth of Credit: Debt Becomes Assets · 52

Chapter 3 Britain: The Island Power That Led the Financial Revolution to the Industrial Revolution

Gaining Maritime Trade Hegemony through Tax Reform · 63

The Seven Years' War: The Final Piece of the Financial Revolution · 69

The Triangle of the Industrial Revolution: Cotton, Iron Ore, and Coal · 71

Chapter 4: The Freedom of Capital Spread by the French Revolution in the Great Plains

A land blessed with natural conditions · 81

The Bourgeoisie That Grew Along with Commercial Capitalism · 85

The Little Ice Age Explodes the Contradictions of the Class System · 90

What "Freedom" in the Market Means After the Great Revolution · 94

A Time to Explore Multi-Scale: The Two Faces of the Belle Époque · 98

2.

The Earth Divided by the Spread of Anti-Capitalism

Chapter 5: The Specter of Communism That Split Russia and Europe in Half

Half-Capitalism Trapped in a Frozen Sea · 118

Was the Great Game a failure of expansionism? · 123

The Limits of Top-Down Reform, Leading to the World's First Communist State · 130

Chapter 6: Germany: The Tragedy of a Latecomer Capitalist Country That Became the Tinder for Fascism

From Division to Unity, the Birth of a Unified Empire · 141

The Battle for "Lebensraum" Plunges the World into War · 147

The Monster's Run: A Mix of Anti-Communism and Capitalism · 153

What do the fascism that swept through Italy, Germany, and Japan have in common? · 157

Chapter 7: The United States: A New Capitalist Power from the Atlantic to the Pacific

Why did Americans throw crates of tea into the ocean? · 165

A Great River that Connects the Divided Territories · 169

Connecting the East and West with the Transcontinental Railroad, and the North and South with the Panama Canal · 173

The Roaring Twenties: The Great Depression That Destroyed the Great Powers · 182

A Multi-Scale Look: The Growing Scale of War with Capitalism · 185

3.

A new world map drawn by capitalism in Wonderland

Chapter 8: China: The Grand Picture of the "One Belt, One Road" Initiative, Spanning Continents and Oceans

The Cultural Revolution: The Worst Madness in History · 209

The Rise of a Great Power, Reborn as the World's Factory · 213

A Modern Silk Road Linking Eurasia and the Indian Ocean · 216

Where's the 21st-century Great Game? · 222

Chapter 9: Vietnam's Natural Geographical Resources Become a Double-Edged Sword

Is a favorable location a crisis or an opportunity? · 229

Climbing the Precarious Ladder of the Global Value Chain · 232

Doi Moi: A Black Hole of Inequality and Climate Crisis · 236

Chapter 10: The Fate of Korea's Neoliberalism Built on Construction

The "Miracle on the Han River": A Multi-Scale Cold War Experience · 243

The Roots of the Myth of Real Estate's Invincibility · 248

Is Korea's Neoliberalism Really a Rosy Future? · 253

A Multi-Scale Look: Why Neoliberalism Repeats Booms and Recessions · 258

Is there a future for the global economy? · 270

Detailed image

Into the book

The birth of capitalism as it exists today is closely related to the expansion of the Ottoman Empire in the 15th and 16th centuries and the subsequent blockade of the Silk Road trade route.

Since investing capital to generate greater profits is the essential mechanism of capitalism, it is only natural that trade would become a central axis of capitalism. It is, in a way, a great paradox that the blockade of trade routes led to the development of capitalism.

---From "Part 1: Maps and Compasses, Capitalism Begins with Gunpowder"

Spain minted the silver coin 'Peso de Ocho' with silver brought from the Americas, and this silver coin established itself as the key currency during the Age of Exploration.

At a time when silver and silver coins were already being used as important currencies around the world, the American continent produced a huge amount of high-quality silver, which was then distributed around the world along Spanish and Portuguese trade ships, establishing itself as a medium of exchange accepted anywhere in the world.

---From "Chapter 1 Spain, the first country to cross the Atlantic"

The Netherlands was the most active and aggressive in entering the herring fishing and processing industry.

As a result, the Netherlands' herring catch and herring product production reached the highest levels in Europe.

Thanks to this, the Netherlands made a lot of money and transformed from a reclaimed land on the periphery of Europe into a wealthy industrial center.

Knowledge of shipbuilding and navigation, which would later become the foundation for Korea's rise to become a maritime power, was also accumulated at this time.

---From "Chapter 2: The Netherlands, the Wind of Credit Economy Blowing from the Far Sea"

The Industrial Revolution brought unprecedented material abundance to humanity by dramatically increasing industrial productivity.

Moreover, it created an environment for the birth of full-fledged modern capitalism and industrial capitalism by realizing economies of scale and markets.

Thus, industrial capitalism, unlike previous commercial capitalism, acquires a clear status as a definite capitalism, that is, as 'classical' capitalism.

So, the British Industrial Revolution was a major turning point in human history, but it was also a major turning point in capitalism that brought about full-fledged capitalism.

---From "Chapter 3 Britain, the power of the island nation that led the financial revolution to the industrial revolution"

The achievements of the French Revolution are not limited to democracy.

The values of freedom and equality spoken of in the revolution also meant freedom and equality in the capital and economy that had been monopolized by the absolute monarchy and the privileged class.

As a result, a way was opened for merchants and industrialists to secure their activities without suffering from social disadvantages or the encroachment of private property, and for farmers to become independent as self-employed farmers, rather than being tenant farmers virtually subordinate to aristocratic landowners.

---From "Chapter 4: Freedom of Capital Spread by the Great Revolution in France and the Plains"

The Soviet economy, which had suffered through World War I, two revolutions, and a civil war, suffered a significant setback.

The economic system was oriented toward a communist planned economy, not a capitalist one.

Unlike Western Europe, Russia was a country where a "half-baked" capitalist revolution from above, led by a powerful, privileged nobility and a monarchy with a largely despotic character, and it was the result of a communist revolution that took place without the experience of a proper middle class growing and a fully free market economy developing.

---From "Chapter 5: The Specter of Communism That Split Russia and Europe in Half"

In 1919, Benito Mussolini turned Italy into the world's first fascist state.

Italy, like Germany, had been divided for hundreds of years before achieving unification in the late 19th century and emerging as a latecomer to capitalism and imperialism.

Unlike Germany, Italy was a victor in World War I, but was excluded from the post-war process by countries such as Britain and France.

The geographical differences that existed even among the European imperialist powers and the advanced capitalist countries were relatively latecomers and had long been divided, so not only was the desire for unification and a wealthy and powerful nation strong, but the country also suffered great losses from World War I, which served as a breeding ground for the rise of extremist ideologies.

---From "Chapter 6: Germany, the Tragedy of a Latecomer Capitalist Country That Became the Tinder for Fascism"

The great rivers that flow through the Great Plains, such as the Mississippi, Missouri, and Ohio Rivers, not only provide water for agriculture but also serve as transportation routes connecting various parts of the United States.

Even before the advent of railroads and roadways, these rivers effectively connected the newly annexed Louisiana to the existing territories.

Furthermore, the efficient transportation of goods facilitated the development of the steel and coal industries along the Great Lakes coast, and even created a geographic link with the western lands that would later be annexed by the United States.

Moreover, New Orleans, the port city at the center of the Louisiana colony, greatly contributed to the development of trade and further enhanced the potential of the United States to emerge as a capitalist power.

---From "Chapter 7: The United States, the New Capitalist Power from the Atlantic to the Pacific"

China had long distanced itself from the modern capitalist economic system, but then transitioned from the one-party dictatorship of the Communist Party to capitalism, specifically the new international division of labor system.

As a result, it became a strange capitalist country that was unable to escape the scale of China, where the one-party dictatorship of the Communist Party firmly controlled even finance and corporations, while simultaneously being reborn as the world's factory in keeping with the changing geographical order of the capitalist world.

---From "Chapter 8: China, the Grand Picture of the 'One Belt, One Road' that Crosses the Continent and the Ocean"

Within the global value chain of the new international division of labor, Vietnam has achieved rapid economic growth by establishing itself as a global factory.

However, economic growth focused on cheap labor is threatening the sustainability of not only Vietnam's economy but also its society and natural environment within the unequal capitalist economic order of neoliberalism and the new international division of labor.

Economic growth driven solely by low-wage labor in the absence of capital accumulation and technological innovation inevitably has clear limitations.

If these problems are not improved, Vietnam runs the risk of being held back by developing neighbors like Cambodia and unable to move beyond the level of a country that can make a living.

---From "Chapter 9 Vietnam, a Natural Geographical Resource that Became a Double-Edged Sword"

However, it would be wrong to dismiss Korean-style neoliberalism solely as a product of the IMF.

This is because, at its foundation, there is a construction-oriented economy that emerged from the large-scale civil engineering and construction projects carried out during the period of ultra-fast, compressed economic growth from the 1960s to the 1980s, which is referred to as the “Miracle on the Han River.”

In other words, the economic system in which national administration and economic policies are centered on civil engineering and construction projects that exploit and develop the land and natural environment can be said to be the root cause of many of the economic and social problems plaguing Korean society today.

---From "Chapter 10: The Fate of Korean Neoliberalism Built on Construction"

Although the global economy continues to achieve quantitative growth, the problems of irregular employment, unemployment, and the gap between rich and poor remain persistent, regardless of country.

With the emphasis on corporate logic and efficiency even in the education sector, the cost of education has skyrocketed worldwide, and the number of young people who are unable to find stable jobs after graduating from college and are struggling with student loans, unable to escape the vicious cycle of poverty is increasing.

In some ways, it seems like the contradictions of the Belle Époque era are being repeated.

Strictly speaking, capitalism is an economic ideology and system predicated on the rational selfishness of humans. However, the very premise that capital accumulation will naturally benefit minorities, the weak, and irregular workers, like overflowing water, seems to be a very uncapitalistic way of thinking.

Since investing capital to generate greater profits is the essential mechanism of capitalism, it is only natural that trade would become a central axis of capitalism. It is, in a way, a great paradox that the blockade of trade routes led to the development of capitalism.

---From "Part 1: Maps and Compasses, Capitalism Begins with Gunpowder"

Spain minted the silver coin 'Peso de Ocho' with silver brought from the Americas, and this silver coin established itself as the key currency during the Age of Exploration.

At a time when silver and silver coins were already being used as important currencies around the world, the American continent produced a huge amount of high-quality silver, which was then distributed around the world along Spanish and Portuguese trade ships, establishing itself as a medium of exchange accepted anywhere in the world.

---From "Chapter 1 Spain, the first country to cross the Atlantic"

The Netherlands was the most active and aggressive in entering the herring fishing and processing industry.

As a result, the Netherlands' herring catch and herring product production reached the highest levels in Europe.

Thanks to this, the Netherlands made a lot of money and transformed from a reclaimed land on the periphery of Europe into a wealthy industrial center.

Knowledge of shipbuilding and navigation, which would later become the foundation for Korea's rise to become a maritime power, was also accumulated at this time.

---From "Chapter 2: The Netherlands, the Wind of Credit Economy Blowing from the Far Sea"

The Industrial Revolution brought unprecedented material abundance to humanity by dramatically increasing industrial productivity.

Moreover, it created an environment for the birth of full-fledged modern capitalism and industrial capitalism by realizing economies of scale and markets.

Thus, industrial capitalism, unlike previous commercial capitalism, acquires a clear status as a definite capitalism, that is, as 'classical' capitalism.

So, the British Industrial Revolution was a major turning point in human history, but it was also a major turning point in capitalism that brought about full-fledged capitalism.

---From "Chapter 3 Britain, the power of the island nation that led the financial revolution to the industrial revolution"

The achievements of the French Revolution are not limited to democracy.

The values of freedom and equality spoken of in the revolution also meant freedom and equality in the capital and economy that had been monopolized by the absolute monarchy and the privileged class.

As a result, a way was opened for merchants and industrialists to secure their activities without suffering from social disadvantages or the encroachment of private property, and for farmers to become independent as self-employed farmers, rather than being tenant farmers virtually subordinate to aristocratic landowners.

---From "Chapter 4: Freedom of Capital Spread by the Great Revolution in France and the Plains"

The Soviet economy, which had suffered through World War I, two revolutions, and a civil war, suffered a significant setback.

The economic system was oriented toward a communist planned economy, not a capitalist one.

Unlike Western Europe, Russia was a country where a "half-baked" capitalist revolution from above, led by a powerful, privileged nobility and a monarchy with a largely despotic character, and it was the result of a communist revolution that took place without the experience of a proper middle class growing and a fully free market economy developing.

---From "Chapter 5: The Specter of Communism That Split Russia and Europe in Half"

In 1919, Benito Mussolini turned Italy into the world's first fascist state.

Italy, like Germany, had been divided for hundreds of years before achieving unification in the late 19th century and emerging as a latecomer to capitalism and imperialism.

Unlike Germany, Italy was a victor in World War I, but was excluded from the post-war process by countries such as Britain and France.

The geographical differences that existed even among the European imperialist powers and the advanced capitalist countries were relatively latecomers and had long been divided, so not only was the desire for unification and a wealthy and powerful nation strong, but the country also suffered great losses from World War I, which served as a breeding ground for the rise of extremist ideologies.

---From "Chapter 6: Germany, the Tragedy of a Latecomer Capitalist Country That Became the Tinder for Fascism"

The great rivers that flow through the Great Plains, such as the Mississippi, Missouri, and Ohio Rivers, not only provide water for agriculture but also serve as transportation routes connecting various parts of the United States.

Even before the advent of railroads and roadways, these rivers effectively connected the newly annexed Louisiana to the existing territories.

Furthermore, the efficient transportation of goods facilitated the development of the steel and coal industries along the Great Lakes coast, and even created a geographic link with the western lands that would later be annexed by the United States.

Moreover, New Orleans, the port city at the center of the Louisiana colony, greatly contributed to the development of trade and further enhanced the potential of the United States to emerge as a capitalist power.

---From "Chapter 7: The United States, the New Capitalist Power from the Atlantic to the Pacific"

China had long distanced itself from the modern capitalist economic system, but then transitioned from the one-party dictatorship of the Communist Party to capitalism, specifically the new international division of labor system.

As a result, it became a strange capitalist country that was unable to escape the scale of China, where the one-party dictatorship of the Communist Party firmly controlled even finance and corporations, while simultaneously being reborn as the world's factory in keeping with the changing geographical order of the capitalist world.

---From "Chapter 8: China, the Grand Picture of the 'One Belt, One Road' that Crosses the Continent and the Ocean"

Within the global value chain of the new international division of labor, Vietnam has achieved rapid economic growth by establishing itself as a global factory.

However, economic growth focused on cheap labor is threatening the sustainability of not only Vietnam's economy but also its society and natural environment within the unequal capitalist economic order of neoliberalism and the new international division of labor.

Economic growth driven solely by low-wage labor in the absence of capital accumulation and technological innovation inevitably has clear limitations.

If these problems are not improved, Vietnam runs the risk of being held back by developing neighbors like Cambodia and unable to move beyond the level of a country that can make a living.

---From "Chapter 9 Vietnam, a Natural Geographical Resource that Became a Double-Edged Sword"

However, it would be wrong to dismiss Korean-style neoliberalism solely as a product of the IMF.

This is because, at its foundation, there is a construction-oriented economy that emerged from the large-scale civil engineering and construction projects carried out during the period of ultra-fast, compressed economic growth from the 1960s to the 1980s, which is referred to as the “Miracle on the Han River.”

In other words, the economic system in which national administration and economic policies are centered on civil engineering and construction projects that exploit and develop the land and natural environment can be said to be the root cause of many of the economic and social problems plaguing Korean society today.

---From "Chapter 10: The Fate of Korean Neoliberalism Built on Construction"

Although the global economy continues to achieve quantitative growth, the problems of irregular employment, unemployment, and the gap between rich and poor remain persistent, regardless of country.

With the emphasis on corporate logic and efficiency even in the education sector, the cost of education has skyrocketed worldwide, and the number of young people who are unable to find stable jobs after graduating from college and are struggling with student loans, unable to escape the vicious cycle of poverty is increasing.

In some ways, it seems like the contradictions of the Belle Époque era are being repeated.

Strictly speaking, capitalism is an economic ideology and system predicated on the rational selfishness of humans. However, the very premise that capital accumulation will naturally benefit minorities, the weak, and irregular workers, like overflowing water, seems to be a very uncapitalistic way of thinking.

---From "A Multi-Scale Look: Why Neoliberalism Repeats Recessions and Booms"

Publisher's Review

“Where did capitalism come from and where is it going?”

Geography: A three-dimensional historical reading we need in the capitalist era

This book examines the geographical aspects of ten countries (Spain, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, France, Russia, Germany, the United States, China, Vietnam, and Korea) from a perspective of topography, resources, and climate, while tracing the connections and flow of historical events that had previously seemed fragmented.

By tracing the past, we can not only understand the processes through which we came to be what we are today, but also obtain historical clues that can help us predict the future and solve new problems we may face.

When we look at the capitalist economy, most people start with the Industrial Revolution in 18th century England and Adam Smith, famous for his 'invisible hand'.

However, this book takes 15th-century Spain as its starting point.

This is because Spain is in fact the country that laid the foundation for today's capitalist system.

In the 15th century, Spain, located on the Iberian Peninsula in western Europe, began to explore new routes to the western ocean when the trade routes to the east of the continent were blocked by the Ottoman Empire.

In the process, a huge amount of high-quality silver was discovered in the colonized American continent, and the currency made from that silver, the peso de ocho, functions like the dollar today.

Thanks to this, Spain became the center of the world's maritime trade network and a hegemonic power in the 16th century.

Beginning with the Spanish voyages, a maritime trade network spanning the globe was formed, and along this network, people, goods, and resources moved more actively between continents. With the introduction of the peso de ocho in trade, the era of full-scale globalization began.

However, Spain failed to foster domestic industries with the money it earned from maritime trade, and the extravagance of the royal family and the nobility, as well as frequent wars, exhausted the national treasury. By the mid-to-late 16th century, Spain had borrowed 60 percent of its GDP from Genoese banks, ultimately declaring default on its debt four times.

In the end, the Netherlands emerged as a new maritime power in the 17th century, replacing Spain, which had achieved the status of a reserve currency country but was unable to pay its debts and fell into decline.

‘Trade’ was also a factor in the growth.

The Netherlands, which had amassed great wealth through the herring industry, which was a staple food for Europeans at the time, sought to acquire even greater wealth through ocean trade.

The problem is that ocean trade requires enormous initial costs and carries significant risks.

In the process, to prepare for contingencies and facilitate capital procurement, joint stock companies were established, with the East India Company at the center, investing private capital, and securities emerged as a medium of exchange with high added value.

The foundation of capitalist credit, such as stock companies, securities, and insurance, which are often heard in today's economic news, was laid at this time.

The economic change at this time is called the 'Fiscal Revolution'.

The winds of financial revolution blew even to the island nation of Britain, and the economy centered on cash and goods began to transform into an economy centered on finance and credit.

It was a signal flare for 'commercial capitalism'.

Britain, which had a sound finances thanks to the financial revolution and had a much higher credit rating than other European countries, was able to borrow a large amount of money for war at relatively low interest rates, which allowed it to win the Seven Years' War against France, the most powerful country at the time and far superior in national power.

The national credit rating, which has a significant impact on the modern national economy, was influential enough to reverse the difference in national power even in the 18th century.

Meanwhile, France's deep-rooted financial difficulties, caused by its defeat in the Seven Years' War and its excessive territorial expansion, worsened further as the Little Ice Age struck in the 18th century.

Eventually, thanks to the development of commercial capitalism, a middle class with economic wealth and specialized economic knowledge grew, leading to a bourgeois revolution, namely the French Revolution.

They legislated freedom of economic activity and the guarantee of private property, further solidifying the roots of capitalism.

These waves of change coincided with the Industrial Revolution in Britain in the late 18th century, and in the 19th century, the scale of the economy and markets greatly expanded, and capitalism was reborn as full-fledged 'industrial capitalism.'

At this time, capitalism was fully established and a new world economic order was established.

In this way, the author retraces the flow of capitalism through geographical elements such as mountain ranges, rivers, terrain, resources, climate, transportation, industry, population, and cities, and meticulously fills in the gaps in economic history that were filled with question marks when reading existing history books.

“How did capitalism establish itself as a global order?”

Capitalism has transformed itself, uniting and then dividing the world.

Capitalism, which sprouted in Europe, crossed the Atlantic and blossomed in the United States.

The United States, which had successfully acquired and annexed territories by taking advantage of the geopolitical order of Europe and the Americas at the time, began with the 13 states on the eastern Atlantic Ocean and succeeded in taking over California on the Pacific Ocean.

This gives us an unprecedented geopolitical and economic advantage in human history, allowing us to access both the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans simultaneously.

This was a unique advantage that only the United States had, something that even other great empires such as Russia, China, India, and the British Empire did not have.

Moreover, the railroads that were being built at that time efficiently connected and integrated the vast territory of the United States in a short period of time.

The continuous construction of transcontinental railroads in the late 19th and early 20th centuries economically integrated the West, the Pacific Coast, and the Middle East.

Furthermore, with the construction of the Panama Canal, the United States gained a geographic advantage that enabled it to lead global shipping and maritime trade, solidifying its position as a new leading power in the capitalist world, surpassing the level of a major power in North America.

This industrial capitalism developed further by expanding its geographical influence and qualitatively, thanks to the development of transportation and communication in the 19th century United States.

However, industrial capitalism, which seemed to be integrating the global economy with the United States at its center, faced a major crisis.

Capitalism, transplanted across the Ural Mountains to Russia, intertwined with Russia's domestic scale, where the middle class had not yet developed properly, and led to the birth of a communist state, dividing Europe in half.

Furthermore, Russia, which emerged as a new capitalist power, brought about the Cold War system that divided the entire world through a power struggle with the United States.

Meanwhile, capitalism transplanted to Germany, coupled with the extreme hyperinflation caused by the defeat in World War I and the Great Depression, was heading towards fascism.

Italy and Japan, latecomers to imperialism and the Industrial Revolution who were in the same situation as Germany, were also influenced by the geopolitics of Lebensraum (the theory that the prosperity of a nation or people is directly linked to securing Lebensraum, the geographic area necessary for population support and industrial development), and caused World War II.

The fascist state's winning streak, which seemed poised to completely swallow up not only the capitalist world but even the communist Soviet Union, was broken in late 1942 and 1943.

From this point on, the odds of defeat became increasingly uncertain, and World War II ended with complete defeat in 1945.

With this, fascism, which threatened capitalism, disappeared from the face of the earth.

In Part 2, we examine the transition from industrial capitalism to modified capitalism within the complex context of the geopolitical and economic strata of Russia, Germany, and the United States.

“Can capitalism overcome the climate crisis and global inequality?”

How to Read the New World Map Drawn by Capitalism in Wonderland

Ironically, it was not the ideology or the state that was the antithesis of capitalism that brought about the crisis of capitalism, which had been flourishing.

The first crisis was the Great Depression that began in the United States in 1929.

The Great Depression devastated the U.S. economy, which lost 30 to 40 percent of its GDP, and its aftereffects spread throughout the capitalist world.

With the United States, the center of capitalism, in this state, other capitalist countries were also bound to fall into the abyss again.

Even before the Great Depression, economists had already recognized the problems of industrial capitalism and were seeking alternatives. The capitalism that emerged during this period was 'modified capitalism.'

Capitalism, which had been pursuing a path of reformist capitalism, faced another crisis in the 1970s. Saudi Arabia, a key member of OPEC, cut oil production to pressure the United States and the Western world, disrupting oil supplies and dealing a fatal blow to the capitalist world.

The capitalist world, which had been expanding externally through oil, which emerged as a new resource to replace coal, was dealt a fatal blow by the resource war and suffered from stagflation, putting it on the verge of collapse.

Accordingly, discussions in Western economic circles about the need to reorganize capitalism began to gain momentum, and 'neoliberalism' became established as the new economic order.

In the 1990s, with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the socialist bloc, capitalism took over the world, leading to a unipolar hegemony led by the United States. Even China and Vietnam, which had adopted socialism, reformed their economic structures to capitalist standards and jumped into the neoliberal wave.

In the process, they are transformed into a market that produces and consumes the goods of capitalist countries.

A significant portion of the so-called manufacturing industry was transferred to developing countries, and advanced countries were responsible only for high value-added industries that were technology-intensive and capital-intensive, creating an economic division of labor structure, or a new international division of labor order.

Part 3 analyzes the light and shadow of capitalist globalization in a three-dimensional way through the geographical framework of countries that played a key role as partners in the new international division of labor, such as China's Belt and Road Initiative, Vietnam's Doi Moi policy, and South Korea's constructionism.

Developed countries have destroyed the natural environment in their pursuit of growth, ultimately leading to a massive disaster that threatens the survival of humanity.

The problem is that these disasters are hitting countries that are just beginning to develop.

By dumping toxic waste at low prices in low-income countries like Africa, developed countries are further undermining the economic and social sustainability of these already environmentally vulnerable regions. (p. 268)

Neoliberalism was considered a global economic trend that even socialist countries could not resist.

However, with the outbreak of the 2008 global financial crisis, the theory of capitalist crisis emerged.

Many mainstream economists failed to predict this economic crisis and failed to come up with realistic economic policies to address it.

Many people have concluded that neoliberalism has lost its vitality.

What happens now, some 15 years later? Neoliberalism still persists, polarization in our society is worsening, and the ecosystem is being destroyed uncontrollably, leading to unprecedented environmental problems like the climate crisis, threatening the very existence of humanity.

The author strongly warns that if these problems “continue or worsen without being meaningfully resolved, capitalism could face its greatest crisis ever, triggering a reaction on a different level than fascism and communism.”

The new international division of labor and global value chains may seem at first glance to be beneficial to the economies of developing countries, but in reality, they are hindering the accumulation of capital and technology in developing countries and exploiting their labor, thereby maintaining and widening the gap between developed and developing countries.

The gap between the South and the North is becoming increasingly serious as the former colonial nations in the Southern Hemisphere are unable to escape the status of developing countries, while the former colonial powers in the Northern Hemisphere, such as the United States and European powers, maintain their status as developed countries.

(…) We can easily observe around us that migrant workers from developing countries are exposed to various types of discrimination in developed countries and are forced into slums or shantytowns.

As these problems accumulate, they lead to deviant and criminal behavior by immigrants, which in turn leads to the spread of anti-immigrant sentiment and xenophobia—in other words, hatred of foreigners—in developed countries. (pp. 261-263)

The global economic and environmental inequality brought about by neoliberal globalization has become a factor in exacerbating environmental problems such as the climate crisis on a global scale by promoting the unfair distribution and use of resources.

Of course, based on this awareness of the problem, there have been movements to resist neoliberalism and seek alternatives for decades.

However, the anti-capitalist and anti-globalization movements centered in Mesoamerica and South America have encountered limitations as a fundamental alternative to neoliberalism, and the Obama administration, which had a post-neoliberal bent, also lost power to Trump, leading to a backlash against his re-election in 2024.

Nonetheless, the author argues that we must face the vast and complex nature of capitalism and not stop challenging it.

I hope that many readers will discover in this book the urgent reasons the author proposes.

Unless a groundbreaking change is made to neoliberalism, the capitalist world economy risks continuing to grow only superficially, while continuing to expand and reproduce multi-scale inequality, ultimately making it difficult to sustain even the economies and environments of advanced countries.

This is precisely why we must cultivate a geographically multi-scale perspective and understanding of neoliberalism and capitalism, and, based on this, seek a sustainable new direction for capitalism and the global economy.

(Page 272)

Geography: A three-dimensional historical reading we need in the capitalist era

This book examines the geographical aspects of ten countries (Spain, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, France, Russia, Germany, the United States, China, Vietnam, and Korea) from a perspective of topography, resources, and climate, while tracing the connections and flow of historical events that had previously seemed fragmented.

By tracing the past, we can not only understand the processes through which we came to be what we are today, but also obtain historical clues that can help us predict the future and solve new problems we may face.

When we look at the capitalist economy, most people start with the Industrial Revolution in 18th century England and Adam Smith, famous for his 'invisible hand'.

However, this book takes 15th-century Spain as its starting point.

This is because Spain is in fact the country that laid the foundation for today's capitalist system.

In the 15th century, Spain, located on the Iberian Peninsula in western Europe, began to explore new routes to the western ocean when the trade routes to the east of the continent were blocked by the Ottoman Empire.

In the process, a huge amount of high-quality silver was discovered in the colonized American continent, and the currency made from that silver, the peso de ocho, functions like the dollar today.

Thanks to this, Spain became the center of the world's maritime trade network and a hegemonic power in the 16th century.

Beginning with the Spanish voyages, a maritime trade network spanning the globe was formed, and along this network, people, goods, and resources moved more actively between continents. With the introduction of the peso de ocho in trade, the era of full-scale globalization began.

However, Spain failed to foster domestic industries with the money it earned from maritime trade, and the extravagance of the royal family and the nobility, as well as frequent wars, exhausted the national treasury. By the mid-to-late 16th century, Spain had borrowed 60 percent of its GDP from Genoese banks, ultimately declaring default on its debt four times.

In the end, the Netherlands emerged as a new maritime power in the 17th century, replacing Spain, which had achieved the status of a reserve currency country but was unable to pay its debts and fell into decline.

‘Trade’ was also a factor in the growth.

The Netherlands, which had amassed great wealth through the herring industry, which was a staple food for Europeans at the time, sought to acquire even greater wealth through ocean trade.

The problem is that ocean trade requires enormous initial costs and carries significant risks.

In the process, to prepare for contingencies and facilitate capital procurement, joint stock companies were established, with the East India Company at the center, investing private capital, and securities emerged as a medium of exchange with high added value.

The foundation of capitalist credit, such as stock companies, securities, and insurance, which are often heard in today's economic news, was laid at this time.

The economic change at this time is called the 'Fiscal Revolution'.

The winds of financial revolution blew even to the island nation of Britain, and the economy centered on cash and goods began to transform into an economy centered on finance and credit.

It was a signal flare for 'commercial capitalism'.

Britain, which had a sound finances thanks to the financial revolution and had a much higher credit rating than other European countries, was able to borrow a large amount of money for war at relatively low interest rates, which allowed it to win the Seven Years' War against France, the most powerful country at the time and far superior in national power.

The national credit rating, which has a significant impact on the modern national economy, was influential enough to reverse the difference in national power even in the 18th century.

Meanwhile, France's deep-rooted financial difficulties, caused by its defeat in the Seven Years' War and its excessive territorial expansion, worsened further as the Little Ice Age struck in the 18th century.

Eventually, thanks to the development of commercial capitalism, a middle class with economic wealth and specialized economic knowledge grew, leading to a bourgeois revolution, namely the French Revolution.

They legislated freedom of economic activity and the guarantee of private property, further solidifying the roots of capitalism.

These waves of change coincided with the Industrial Revolution in Britain in the late 18th century, and in the 19th century, the scale of the economy and markets greatly expanded, and capitalism was reborn as full-fledged 'industrial capitalism.'

At this time, capitalism was fully established and a new world economic order was established.

In this way, the author retraces the flow of capitalism through geographical elements such as mountain ranges, rivers, terrain, resources, climate, transportation, industry, population, and cities, and meticulously fills in the gaps in economic history that were filled with question marks when reading existing history books.

“How did capitalism establish itself as a global order?”

Capitalism has transformed itself, uniting and then dividing the world.

Capitalism, which sprouted in Europe, crossed the Atlantic and blossomed in the United States.

The United States, which had successfully acquired and annexed territories by taking advantage of the geopolitical order of Europe and the Americas at the time, began with the 13 states on the eastern Atlantic Ocean and succeeded in taking over California on the Pacific Ocean.

This gives us an unprecedented geopolitical and economic advantage in human history, allowing us to access both the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans simultaneously.

This was a unique advantage that only the United States had, something that even other great empires such as Russia, China, India, and the British Empire did not have.

Moreover, the railroads that were being built at that time efficiently connected and integrated the vast territory of the United States in a short period of time.

The continuous construction of transcontinental railroads in the late 19th and early 20th centuries economically integrated the West, the Pacific Coast, and the Middle East.

Furthermore, with the construction of the Panama Canal, the United States gained a geographic advantage that enabled it to lead global shipping and maritime trade, solidifying its position as a new leading power in the capitalist world, surpassing the level of a major power in North America.

This industrial capitalism developed further by expanding its geographical influence and qualitatively, thanks to the development of transportation and communication in the 19th century United States.

However, industrial capitalism, which seemed to be integrating the global economy with the United States at its center, faced a major crisis.

Capitalism, transplanted across the Ural Mountains to Russia, intertwined with Russia's domestic scale, where the middle class had not yet developed properly, and led to the birth of a communist state, dividing Europe in half.

Furthermore, Russia, which emerged as a new capitalist power, brought about the Cold War system that divided the entire world through a power struggle with the United States.

Meanwhile, capitalism transplanted to Germany, coupled with the extreme hyperinflation caused by the defeat in World War I and the Great Depression, was heading towards fascism.

Italy and Japan, latecomers to imperialism and the Industrial Revolution who were in the same situation as Germany, were also influenced by the geopolitics of Lebensraum (the theory that the prosperity of a nation or people is directly linked to securing Lebensraum, the geographic area necessary for population support and industrial development), and caused World War II.

The fascist state's winning streak, which seemed poised to completely swallow up not only the capitalist world but even the communist Soviet Union, was broken in late 1942 and 1943.

From this point on, the odds of defeat became increasingly uncertain, and World War II ended with complete defeat in 1945.

With this, fascism, which threatened capitalism, disappeared from the face of the earth.

In Part 2, we examine the transition from industrial capitalism to modified capitalism within the complex context of the geopolitical and economic strata of Russia, Germany, and the United States.

“Can capitalism overcome the climate crisis and global inequality?”

How to Read the New World Map Drawn by Capitalism in Wonderland

Ironically, it was not the ideology or the state that was the antithesis of capitalism that brought about the crisis of capitalism, which had been flourishing.

The first crisis was the Great Depression that began in the United States in 1929.

The Great Depression devastated the U.S. economy, which lost 30 to 40 percent of its GDP, and its aftereffects spread throughout the capitalist world.

With the United States, the center of capitalism, in this state, other capitalist countries were also bound to fall into the abyss again.

Even before the Great Depression, economists had already recognized the problems of industrial capitalism and were seeking alternatives. The capitalism that emerged during this period was 'modified capitalism.'

Capitalism, which had been pursuing a path of reformist capitalism, faced another crisis in the 1970s. Saudi Arabia, a key member of OPEC, cut oil production to pressure the United States and the Western world, disrupting oil supplies and dealing a fatal blow to the capitalist world.

The capitalist world, which had been expanding externally through oil, which emerged as a new resource to replace coal, was dealt a fatal blow by the resource war and suffered from stagflation, putting it on the verge of collapse.

Accordingly, discussions in Western economic circles about the need to reorganize capitalism began to gain momentum, and 'neoliberalism' became established as the new economic order.

In the 1990s, with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the socialist bloc, capitalism took over the world, leading to a unipolar hegemony led by the United States. Even China and Vietnam, which had adopted socialism, reformed their economic structures to capitalist standards and jumped into the neoliberal wave.

In the process, they are transformed into a market that produces and consumes the goods of capitalist countries.

A significant portion of the so-called manufacturing industry was transferred to developing countries, and advanced countries were responsible only for high value-added industries that were technology-intensive and capital-intensive, creating an economic division of labor structure, or a new international division of labor order.

Part 3 analyzes the light and shadow of capitalist globalization in a three-dimensional way through the geographical framework of countries that played a key role as partners in the new international division of labor, such as China's Belt and Road Initiative, Vietnam's Doi Moi policy, and South Korea's constructionism.

Developed countries have destroyed the natural environment in their pursuit of growth, ultimately leading to a massive disaster that threatens the survival of humanity.

The problem is that these disasters are hitting countries that are just beginning to develop.

By dumping toxic waste at low prices in low-income countries like Africa, developed countries are further undermining the economic and social sustainability of these already environmentally vulnerable regions. (p. 268)

Neoliberalism was considered a global economic trend that even socialist countries could not resist.

However, with the outbreak of the 2008 global financial crisis, the theory of capitalist crisis emerged.

Many mainstream economists failed to predict this economic crisis and failed to come up with realistic economic policies to address it.

Many people have concluded that neoliberalism has lost its vitality.

What happens now, some 15 years later? Neoliberalism still persists, polarization in our society is worsening, and the ecosystem is being destroyed uncontrollably, leading to unprecedented environmental problems like the climate crisis, threatening the very existence of humanity.

The author strongly warns that if these problems “continue or worsen without being meaningfully resolved, capitalism could face its greatest crisis ever, triggering a reaction on a different level than fascism and communism.”

The new international division of labor and global value chains may seem at first glance to be beneficial to the economies of developing countries, but in reality, they are hindering the accumulation of capital and technology in developing countries and exploiting their labor, thereby maintaining and widening the gap between developed and developing countries.

The gap between the South and the North is becoming increasingly serious as the former colonial nations in the Southern Hemisphere are unable to escape the status of developing countries, while the former colonial powers in the Northern Hemisphere, such as the United States and European powers, maintain their status as developed countries.

(…) We can easily observe around us that migrant workers from developing countries are exposed to various types of discrimination in developed countries and are forced into slums or shantytowns.

As these problems accumulate, they lead to deviant and criminal behavior by immigrants, which in turn leads to the spread of anti-immigrant sentiment and xenophobia—in other words, hatred of foreigners—in developed countries. (pp. 261-263)

The global economic and environmental inequality brought about by neoliberal globalization has become a factor in exacerbating environmental problems such as the climate crisis on a global scale by promoting the unfair distribution and use of resources.

Of course, based on this awareness of the problem, there have been movements to resist neoliberalism and seek alternatives for decades.

However, the anti-capitalist and anti-globalization movements centered in Mesoamerica and South America have encountered limitations as a fundamental alternative to neoliberalism, and the Obama administration, which had a post-neoliberal bent, also lost power to Trump, leading to a backlash against his re-election in 2024.

Nonetheless, the author argues that we must face the vast and complex nature of capitalism and not stop challenging it.

I hope that many readers will discover in this book the urgent reasons the author proposes.

Unless a groundbreaking change is made to neoliberalism, the capitalist world economy risks continuing to grow only superficially, while continuing to expand and reproduce multi-scale inequality, ultimately making it difficult to sustain even the economies and environments of advanced countries.

This is precisely why we must cultivate a geographically multi-scale perspective and understanding of neoliberalism and capitalism, and, based on this, seek a sustainable new direction for capitalism and the global economy.

(Page 272)

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: January 10, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 288 pages | 384g | 143*210*19mm

- ISBN13: 9791191842784

- ISBN10: 1191842789

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)