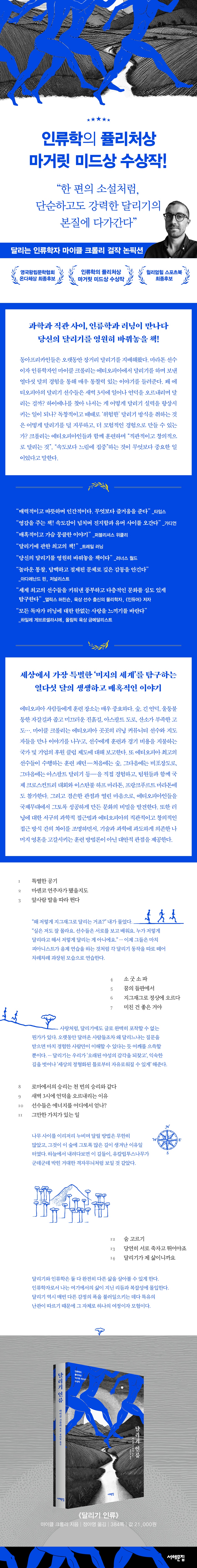

Running Humanity

|

Description

Book Introduction

"Like a novel, it approaches the simple yet powerful essence of running."

A masterpiece of nonfiction by running anthropologist Michael Crowley.

This is the 2022 winner of the Margaret Mead Award, the most prestigious award in the field of anthropology.

Michael Crowley, a marathon runner and anthropologist, shares insightful stories from his fifteen months running in Ethiopia.

Why do Ethiopian runners wake up at 3 a.m. to race up and down hills? How does hunting hyenas improve running performance? How can adopting unique and sometimes "risky" running styles make running less tedious and more adventurous?

Crowley says the most important thing was to “run intuitively and creatively” and “focus on slowness rather than speed.”

And with a humble perspective and open mind, it illuminates the differences between the Western scientific approach to running and the Ethiopian intuitive and creative approach, offering an alternative perspective to the soul-draining training methodologies that rely too heavily on technology and science.

A masterpiece of nonfiction by running anthropologist Michael Crowley.

This is the 2022 winner of the Margaret Mead Award, the most prestigious award in the field of anthropology.

Michael Crowley, a marathon runner and anthropologist, shares insightful stories from his fifteen months running in Ethiopia.

Why do Ethiopian runners wake up at 3 a.m. to race up and down hills? How does hunting hyenas improve running performance? How can adopting unique and sometimes "risky" running styles make running less tedious and more adventurous?

Crowley says the most important thing was to “run intuitively and creatively” and “focus on slowness rather than speed.”

And with a humble perspective and open mind, it illuminates the differences between the Western scientific approach to running and the Ethiopian intuitive and creative approach, offering an alternative perspective to the soul-draining training methodologies that rely too heavily on technology and science.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

1.

Special air

2.

I might have become a Masenko player

3.

Run after the person in front

4.

So good so far

5.

In the field of dreams

6.

Climb to the top in a zigzag manner

7.

Crazy is good

8.

A victory in Rome is like a thousand victories.

9.

Why are you running up and down the hill at 3 a.m.?

10.

Where do athletes get their energy?

11.

It's worth it

12.

Take a breath

13.

Of course we have to run to each other's death

14.

Because running is my life

Special air

2.

I might have become a Masenko player

3.

Run after the person in front

4.

So good so far

5.

In the field of dreams

6.

Climb to the top in a zigzag manner

7.

Crazy is good

8.

A victory in Rome is like a thousand victories.

9.

Why are you running up and down the hill at 3 a.m.?

10.

Where do athletes get their energy?

11.

It's worth it

12.

Take a breath

13.

Of course we have to run to each other's death

14.

Because running is my life

Detailed image

Into the book

It occurred to me that running and anthropology could do similar things.

Both allow you to live completely different lives.

As an anthropologist, I am immersed in the rhythms and complexities of life in Addis Ababa.

Running, too, evokes a range of emotions each time, and long-distance training comes with its own unique challenges, making it a journey and an adventure in itself.

--- p.28

“Why are you running in a zigzag pattern like that?” I asked.

“Actually, I don’t know either.

Players watch and learn from each other.

“No one told me to run like that, so I didn’t run like that.” This remark also surprised me.

Do you admit that players learn not only from the coach but also from each other? (…) “What kind of training is that?” “It’s just warming up.

“It’s like the act of sowing seeds while praying for a harvest.” Needless to say, I have never seen or heard of such a training.

Now they practice each running movement separately and exaggeratedly, one after another, like a pianist practicing scales.

--- p.35

Ethiopian and Kenyan runners are often portrayed in an overly romantic way.

Representative images include children from mountainous regions walking to school barefoot and people running to escape poverty.

Benoit wanted to make it clear that the poorest people in Ethiopia are not runners.

“To become an athlete, you need some support from your family.

“You also need to have the time and energy to train.”

--- p.53

Like love, there is something about running that cannot be perfectly captured in words.

Even people who have been running for a long time just shrug their shoulders when asked why they run, as if only those who have experienced it can understand.

If I had to give a reason, (…) I think it might be because of resistance to comfort.

(…) Running allows us to ‘reclaim our old wild sense’ and ‘free ourselves from the stereotypes of the world’ by leaving the familiar path.

--- p.74~75

We ran down the muddy slope at the edge of the road, then onto a dirt road with deep ruts.

I followed the trail the horse cart had left, dodging rocks and puddles.

When the two of them said yesterday that it was a 'good field for running', I expected flat, dry ground.

Besides, he said he was going to run 'lightly' today too.

We zigzagged across the steep, damp fields.

The grass, soaked in dew, clung to my feet.

“It doesn’t seem… light… to me…” I managed to spit out the words, panting for breath.

It was like running on a giant sponge.

With every step I took, I felt like all the energy in my body was being sucked into the ground.

(…) In Ethiopia, the term ‘heavy’ weather meant air that was hard to breathe and ground that sapped energy from underfoot.

The air felt heavy rather than thin, and no matter how deeply I tried to inhale, it didn't seem to reach my lungs.

At this altitude, I thought I would be out of breath and gasping for breath, but in reality, my brain seemed to apply the brakes before I could even get that far.

--- p.88~89

'Following the footsteps of another athlete' means running to that person's rhythm and using that person's energy as your own.

Therefore, Addis Ababa players often described taking the lead or acting as pacemaker as 'carrying the burden on their teammates'.

The players had to learn to share their energy with each other and develop together.

There is an Amharic proverb that captures the value of teamwork well:

"A few threads can tie a lion." Training wasn't a survival-of-the-fittest competition conducted individually, but rather a process of working together.

--- p.98

The conversations between coaches and players on the bus after training were largely focused on finding the most effective combination of weekly training locations and surfaces at that time.

When there was no competition scheduled, I trained about three times a week in 'high altitudes' or 'cold areas'.

This week has been really tough.

Sometimes, we trained at altitudes of over 2700 meters above sea level three times in a row.

Usually, we trained by mixing different terrains.

On Mondays, we trained at high altitudes, and on Wednesdays, we focused on 'speed' training at lower altitudes.

And on Fridays, we trained alternately at Sebeta, which is 2,200 meters above sea level, and Sendapa, which is over 2,600 meters above sea level.

As important as the training location was the type of ground.

The key was to find the right combination of 'hard surfaces' such as asphalt or rough roads and 'soft surfaces' such as grass or forest paths.

--- p.106~107

The forest area we ran in this morning had hundreds of paths crisscrossing between the eucalyptus trees.

It was a path made by the footsteps of thousands and tens of thousands of people.

If I were you, I would have followed these paths without thinking, but Chedat deliberately avoided them, choosing a new path to follow, treading on the less-trodden ground between the trees.

There were endless ways to run through the trees, which was probably why there were so many paths in this forest.

From the sky, these roads would appear like a giant grid pattern dotted with eucalyptus trees.

--- p.151

The final stage was asphalt training.

Even Ethiopia's most experienced marathon runners trained on asphalt roads at most once a week, always on Fridays.

No one who had just started running or was not yet 18 years old ran on asphalt.

Birhanu also started running on the road only after running for four years in Gondar.

In Ethiopia, asphalt was considered a rather harsh surface for running.

Because it consumed energy.

(…) “I must have run halfway to Rome!” I said.

“That’s ridiculous,” Birhanu replied calmly.

Birhanu's preparation for the competition seemed to encapsulate the growth trajectory of a young athlete.

First, he trained in the forest for ten days to build up his stamina, then he ran the Coroconchi, and finally he improved his speed by running on asphalt roads.

This process, in other words, was a process of gradual adaptation.

First it was about adapting to the ground, then adapting to the speed.

--- p.202~203

Ethiopia had a better institutional foundation and various competitions supporting athletics than many European countries.

All the athletics clubs in Ethiopia's first division, whether in track, road or cross-country, paid their athletes salaries that were sufficient to support them without having to work another job.

Most of these clubs are directly linked to government agencies, the Armed Forces Athletics Club being the most representative example.

Other major clubs included the Federal Police, Ethiopian Electricity Corporation, Ethiopian Commercial Bank (Bank), and the Federal Prisons Club.

There is also a network of small clubs, primarily run by junior players, which provide support not only for training but also for meals, accommodation, and equipment.

--- p.224

It cannot be overemphasized how important it is to share the responsibility of being a pacemaker during training and who you choose to train with.

(…) Coach Meseret made sure that even the players recovering from injuries shared the ‘responsibility’ of being pacemakers, and made sure that the players felt that this ‘duty’, which they considered so important, was shared equally by all.

--- p.259~260

“It’s open on all sides here,” he said, pointing with his hand.

The track was a small, towering plateau with a steep slope extending outwards in either direction.

He pointed to a slope.

“Do you see the clouds down there?” he asked, then pointed out that the track was located at 3,100 meters above sea level.

“Sports scientists say it’s too high up here.

“It’s too high, so it’s not advisable to train here.” Desalin seemed lost in thought for a moment.

“What do you think, Coach?” I asked cautiously.

“That would be desirable.

“If you go somewhere else, you can win easily.” It was a short and bland answer.

--- p.310

The next morning we ran through the forests of Mount Guna, the second highest mountain in Ethiopia.

By the time we reached the edge of the forest, everyone was shivering violently.

The temperature had dropped again to near freezing and an icy rain was pouring down.

We ran in a long line, with Desalines in the lead.

Desalines said that since he starts 'high-intensity' interval training tomorrow, his goal today is to run as slowly as possible.

But in my experience, in these cases, coaches often deliberately choose difficult and tricky terrain to run on.

This was to prevent players in good physical condition from unknowingly increasing their speed.

As I looked up at the mountain before me, I had a gut feeling that I was about to experience the essence of this approach.

(…) I thought that this was not just running training, but almost military training.

“Coach, sometimes I think you’re crazy,” Birhanu whispered as he pushed me up onto the wall.

--- p.318~319

In fact, one of the most striking differences when comparing Ethiopian and British running styles was the variety of pace and movement incorporated into training sessions.

In Edinburgh, I always started running as soon as I left home, running every kilometre in about four minutes.

And when I felt like it, I did some light stretching in front of my house.

In Ethiopia, even when running the same race, the first kilometer was often run in 8 minutes, and the last kilometer was often run much faster than 4 minutes.

After the run, there was a series of acceleration drills ending in sprints and plyometric exercises of increasing intensity.

I don't know how many days I've had hamstring pain since I first came here and did this workout.

--- p.334

Running in a group definitely makes a big difference.

And the difference was far more fundamental than the aerodynamic gains Nike and Ineos were hoping to achieve in their quest to break the two-hour marathon barrier.

I am reminded of what Kipchoge said immediately after the race in Monza, Italy.

“I want to thank my pacemakers for encouraging me as we ran together.” That was my feeling as I advanced each kilometer in Frankfurt.

The group's energy was more than just the sum of the individual players' energies, and we moved forward together as one unit.

(…) The final stretch of the Frankfurt Marathon was truly spectacular.

The final 100 meters the athletes ran were on a red-carpeted track inside the Festhalle.

I entered the stadium the moment Meskerem crossed the finish line, and after running dozens of kilometers outside, I was suddenly confronted with a dazzling interior filled with confetti and lights, and my senses were overwhelmed.

Although my head was a little dizzy, I enjoyed the atmosphere and headed towards the finish line.

And finally, he finished the race with a time of 2:20:53.

Both allow you to live completely different lives.

As an anthropologist, I am immersed in the rhythms and complexities of life in Addis Ababa.

Running, too, evokes a range of emotions each time, and long-distance training comes with its own unique challenges, making it a journey and an adventure in itself.

--- p.28

“Why are you running in a zigzag pattern like that?” I asked.

“Actually, I don’t know either.

Players watch and learn from each other.

“No one told me to run like that, so I didn’t run like that.” This remark also surprised me.

Do you admit that players learn not only from the coach but also from each other? (…) “What kind of training is that?” “It’s just warming up.

“It’s like the act of sowing seeds while praying for a harvest.” Needless to say, I have never seen or heard of such a training.

Now they practice each running movement separately and exaggeratedly, one after another, like a pianist practicing scales.

--- p.35

Ethiopian and Kenyan runners are often portrayed in an overly romantic way.

Representative images include children from mountainous regions walking to school barefoot and people running to escape poverty.

Benoit wanted to make it clear that the poorest people in Ethiopia are not runners.

“To become an athlete, you need some support from your family.

“You also need to have the time and energy to train.”

--- p.53

Like love, there is something about running that cannot be perfectly captured in words.

Even people who have been running for a long time just shrug their shoulders when asked why they run, as if only those who have experienced it can understand.

If I had to give a reason, (…) I think it might be because of resistance to comfort.

(…) Running allows us to ‘reclaim our old wild sense’ and ‘free ourselves from the stereotypes of the world’ by leaving the familiar path.

--- p.74~75

We ran down the muddy slope at the edge of the road, then onto a dirt road with deep ruts.

I followed the trail the horse cart had left, dodging rocks and puddles.

When the two of them said yesterday that it was a 'good field for running', I expected flat, dry ground.

Besides, he said he was going to run 'lightly' today too.

We zigzagged across the steep, damp fields.

The grass, soaked in dew, clung to my feet.

“It doesn’t seem… light… to me…” I managed to spit out the words, panting for breath.

It was like running on a giant sponge.

With every step I took, I felt like all the energy in my body was being sucked into the ground.

(…) In Ethiopia, the term ‘heavy’ weather meant air that was hard to breathe and ground that sapped energy from underfoot.

The air felt heavy rather than thin, and no matter how deeply I tried to inhale, it didn't seem to reach my lungs.

At this altitude, I thought I would be out of breath and gasping for breath, but in reality, my brain seemed to apply the brakes before I could even get that far.

--- p.88~89

'Following the footsteps of another athlete' means running to that person's rhythm and using that person's energy as your own.

Therefore, Addis Ababa players often described taking the lead or acting as pacemaker as 'carrying the burden on their teammates'.

The players had to learn to share their energy with each other and develop together.

There is an Amharic proverb that captures the value of teamwork well:

"A few threads can tie a lion." Training wasn't a survival-of-the-fittest competition conducted individually, but rather a process of working together.

--- p.98

The conversations between coaches and players on the bus after training were largely focused on finding the most effective combination of weekly training locations and surfaces at that time.

When there was no competition scheduled, I trained about three times a week in 'high altitudes' or 'cold areas'.

This week has been really tough.

Sometimes, we trained at altitudes of over 2700 meters above sea level three times in a row.

Usually, we trained by mixing different terrains.

On Mondays, we trained at high altitudes, and on Wednesdays, we focused on 'speed' training at lower altitudes.

And on Fridays, we trained alternately at Sebeta, which is 2,200 meters above sea level, and Sendapa, which is over 2,600 meters above sea level.

As important as the training location was the type of ground.

The key was to find the right combination of 'hard surfaces' such as asphalt or rough roads and 'soft surfaces' such as grass or forest paths.

--- p.106~107

The forest area we ran in this morning had hundreds of paths crisscrossing between the eucalyptus trees.

It was a path made by the footsteps of thousands and tens of thousands of people.

If I were you, I would have followed these paths without thinking, but Chedat deliberately avoided them, choosing a new path to follow, treading on the less-trodden ground between the trees.

There were endless ways to run through the trees, which was probably why there were so many paths in this forest.

From the sky, these roads would appear like a giant grid pattern dotted with eucalyptus trees.

--- p.151

The final stage was asphalt training.

Even Ethiopia's most experienced marathon runners trained on asphalt roads at most once a week, always on Fridays.

No one who had just started running or was not yet 18 years old ran on asphalt.

Birhanu also started running on the road only after running for four years in Gondar.

In Ethiopia, asphalt was considered a rather harsh surface for running.

Because it consumed energy.

(…) “I must have run halfway to Rome!” I said.

“That’s ridiculous,” Birhanu replied calmly.

Birhanu's preparation for the competition seemed to encapsulate the growth trajectory of a young athlete.

First, he trained in the forest for ten days to build up his stamina, then he ran the Coroconchi, and finally he improved his speed by running on asphalt roads.

This process, in other words, was a process of gradual adaptation.

First it was about adapting to the ground, then adapting to the speed.

--- p.202~203

Ethiopia had a better institutional foundation and various competitions supporting athletics than many European countries.

All the athletics clubs in Ethiopia's first division, whether in track, road or cross-country, paid their athletes salaries that were sufficient to support them without having to work another job.

Most of these clubs are directly linked to government agencies, the Armed Forces Athletics Club being the most representative example.

Other major clubs included the Federal Police, Ethiopian Electricity Corporation, Ethiopian Commercial Bank (Bank), and the Federal Prisons Club.

There is also a network of small clubs, primarily run by junior players, which provide support not only for training but also for meals, accommodation, and equipment.

--- p.224

It cannot be overemphasized how important it is to share the responsibility of being a pacemaker during training and who you choose to train with.

(…) Coach Meseret made sure that even the players recovering from injuries shared the ‘responsibility’ of being pacemakers, and made sure that the players felt that this ‘duty’, which they considered so important, was shared equally by all.

--- p.259~260

“It’s open on all sides here,” he said, pointing with his hand.

The track was a small, towering plateau with a steep slope extending outwards in either direction.

He pointed to a slope.

“Do you see the clouds down there?” he asked, then pointed out that the track was located at 3,100 meters above sea level.

“Sports scientists say it’s too high up here.

“It’s too high, so it’s not advisable to train here.” Desalin seemed lost in thought for a moment.

“What do you think, Coach?” I asked cautiously.

“That would be desirable.

“If you go somewhere else, you can win easily.” It was a short and bland answer.

--- p.310

The next morning we ran through the forests of Mount Guna, the second highest mountain in Ethiopia.

By the time we reached the edge of the forest, everyone was shivering violently.

The temperature had dropped again to near freezing and an icy rain was pouring down.

We ran in a long line, with Desalines in the lead.

Desalines said that since he starts 'high-intensity' interval training tomorrow, his goal today is to run as slowly as possible.

But in my experience, in these cases, coaches often deliberately choose difficult and tricky terrain to run on.

This was to prevent players in good physical condition from unknowingly increasing their speed.

As I looked up at the mountain before me, I had a gut feeling that I was about to experience the essence of this approach.

(…) I thought that this was not just running training, but almost military training.

“Coach, sometimes I think you’re crazy,” Birhanu whispered as he pushed me up onto the wall.

--- p.318~319

In fact, one of the most striking differences when comparing Ethiopian and British running styles was the variety of pace and movement incorporated into training sessions.

In Edinburgh, I always started running as soon as I left home, running every kilometre in about four minutes.

And when I felt like it, I did some light stretching in front of my house.

In Ethiopia, even when running the same race, the first kilometer was often run in 8 minutes, and the last kilometer was often run much faster than 4 minutes.

After the run, there was a series of acceleration drills ending in sprints and plyometric exercises of increasing intensity.

I don't know how many days I've had hamstring pain since I first came here and did this workout.

--- p.334

Running in a group definitely makes a big difference.

And the difference was far more fundamental than the aerodynamic gains Nike and Ineos were hoping to achieve in their quest to break the two-hour marathon barrier.

I am reminded of what Kipchoge said immediately after the race in Monza, Italy.

“I want to thank my pacemakers for encouraging me as we ran together.” That was my feeling as I advanced each kilometer in Frankfurt.

The group's energy was more than just the sum of the individual players' energies, and we moved forward together as one unit.

(…) The final stretch of the Frankfurt Marathon was truly spectacular.

The final 100 meters the athletes ran were on a red-carpeted track inside the Festhalle.

I entered the stadium the moment Meskerem crossed the finish line, and after running dozens of kilometers outside, I was suddenly confronted with a dazzling interior filled with confetti and lights, and my senses were overwhelmed.

Although my head was a little dizzy, I enjoyed the atmosphere and headed towards the finish line.

And finally, he finished the race with a time of 2:20:53.

--- p.374~376

Publisher's Review

“Like a novel, simple yet powerful

“Getting closer to the essence of running”

Michael Crowley, the running anthropologist, a masterpiece of nonfiction

★Winner of the Margaret Mead Award, the Pulitzer Prize for Anthropology!

★Finalist for the Royal Society of Literature's Ondaatje Award

★William Hill Sportsbook Finalist

Between science and intuition, reaching the essence of running—a vivid and captivating fifteen-month journey exploring the world's most extraordinary unknown.

East Africans have long dominated long-distance running.

Michael Crowley, a marathon runner and anthropologist, shares insightful stories from his fifteen months of running in Ethiopia.

He trains with Ethiopians and feels that “science doesn’t work.”

And he says that the most important thing was to “run intuitively and creatively” and “focus on slowness rather than speed.”

Why do Ethiopian runners wake up at 3 a.m. to race up and down hills? How does hunting hyenas improve running performance? How can adopting unique and sometimes "risky" running styles make running less tedious and more adventurous? If you're ready, let's head into the forest together.

★“Charming, warm and human.

“It gives me pleasure above all else” _The Times

★“An inspiring book! Fast-paced and daring, it moves between seriousness and humor.” _The Guardian

★“A captivating and heartwarming story” _Publisher's Weekly

★“The Best Book on Running!” Trail Running

★“The book that will change your running forever” _Runner's World

★“Amazing insight, a simple and restrained style that leaves a deep impression” _Adarenand Finn, journalist

★“An in-depth exploration of the rich, multi-layered culture that has nurtured the world’s greatest athletes.” _Alex Hutchinson, former track and field athlete, physicist, and author of Endurance

★“I hope every reader will feel an unwavering love for running.” _Haile Gebrselassie, Olympic track and field gold medalist

Between science and intuition, getting to the heart of running—

The book that will change your running forever!

Training grounds are very important to Ethiopians.

Forests, long hills, bumpy gravel roads and narrow, slippery mud roads, asphalt roads, oxygen-deprived altitudes… .

Michael Crowley speaks with athletes and leaders in the running community across Ethiopia and reports on the state-sponsored club system, which pays for athletes' training and competition expenses.

He also experiences firsthand the training patterns of Ethiopia's top athletes—first in the forest, then on dirt roads, then on asphalt—and participates with his team in international cross-country races, the Istanbul Half Marathon, and the Frankfurt Marathon.

We also witness the impact that 1960s Olympic marathon gold medalist Abebe Bikila still has on Ethiopia, and talk to 92-year-old Wami Viratu, a fellow runner who was even faster than Abebe and is still revered as a hero…

With a humble perspective and an open mind, Crowley uncovers the cultural secrets that have made Ethiopians so successful on the international stage.

And by highlighting the differences between the Western scientific approach to running and the Ethiopian intuitive and creative approach, it offers an alternative perspective to the soul-depleting training methodologies that rely too heavily on technology and science.

With astonishing insight, a clean, understated style, and a fast-paced narrative that alternates between seriousness and humor, Crowley has written a truly remarkable book about running and humanity, delving deeply into the rich, multi-layered culture that has nurtured the world's greatest athletes.

“Getting closer to the essence of running”

Michael Crowley, the running anthropologist, a masterpiece of nonfiction

★Winner of the Margaret Mead Award, the Pulitzer Prize for Anthropology!

★Finalist for the Royal Society of Literature's Ondaatje Award

★William Hill Sportsbook Finalist

Between science and intuition, reaching the essence of running—a vivid and captivating fifteen-month journey exploring the world's most extraordinary unknown.

East Africans have long dominated long-distance running.

Michael Crowley, a marathon runner and anthropologist, shares insightful stories from his fifteen months of running in Ethiopia.

He trains with Ethiopians and feels that “science doesn’t work.”

And he says that the most important thing was to “run intuitively and creatively” and “focus on slowness rather than speed.”

Why do Ethiopian runners wake up at 3 a.m. to race up and down hills? How does hunting hyenas improve running performance? How can adopting unique and sometimes "risky" running styles make running less tedious and more adventurous? If you're ready, let's head into the forest together.

★“Charming, warm and human.

“It gives me pleasure above all else” _The Times

★“An inspiring book! Fast-paced and daring, it moves between seriousness and humor.” _The Guardian

★“A captivating and heartwarming story” _Publisher's Weekly

★“The Best Book on Running!” Trail Running

★“The book that will change your running forever” _Runner's World

★“Amazing insight, a simple and restrained style that leaves a deep impression” _Adarenand Finn, journalist

★“An in-depth exploration of the rich, multi-layered culture that has nurtured the world’s greatest athletes.” _Alex Hutchinson, former track and field athlete, physicist, and author of Endurance

★“I hope every reader will feel an unwavering love for running.” _Haile Gebrselassie, Olympic track and field gold medalist

Between science and intuition, getting to the heart of running—

The book that will change your running forever!

Training grounds are very important to Ethiopians.

Forests, long hills, bumpy gravel roads and narrow, slippery mud roads, asphalt roads, oxygen-deprived altitudes… .

Michael Crowley speaks with athletes and leaders in the running community across Ethiopia and reports on the state-sponsored club system, which pays for athletes' training and competition expenses.

He also experiences firsthand the training patterns of Ethiopia's top athletes—first in the forest, then on dirt roads, then on asphalt—and participates with his team in international cross-country races, the Istanbul Half Marathon, and the Frankfurt Marathon.

We also witness the impact that 1960s Olympic marathon gold medalist Abebe Bikila still has on Ethiopia, and talk to 92-year-old Wami Viratu, a fellow runner who was even faster than Abebe and is still revered as a hero…

With a humble perspective and an open mind, Crowley uncovers the cultural secrets that have made Ethiopians so successful on the international stage.

And by highlighting the differences between the Western scientific approach to running and the Ethiopian intuitive and creative approach, it offers an alternative perspective to the soul-depleting training methodologies that rely too heavily on technology and science.

With astonishing insight, a clean, understated style, and a fast-paced narrative that alternates between seriousness and humor, Crowley has written a truly remarkable book about running and humanity, delving deeply into the rich, multi-layered culture that has nurtured the world's greatest athletes.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: September 15, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 384 pages | 484g | 135*210*24mm

- ISBN13: 9791194413578

- ISBN10: 1194413579

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)