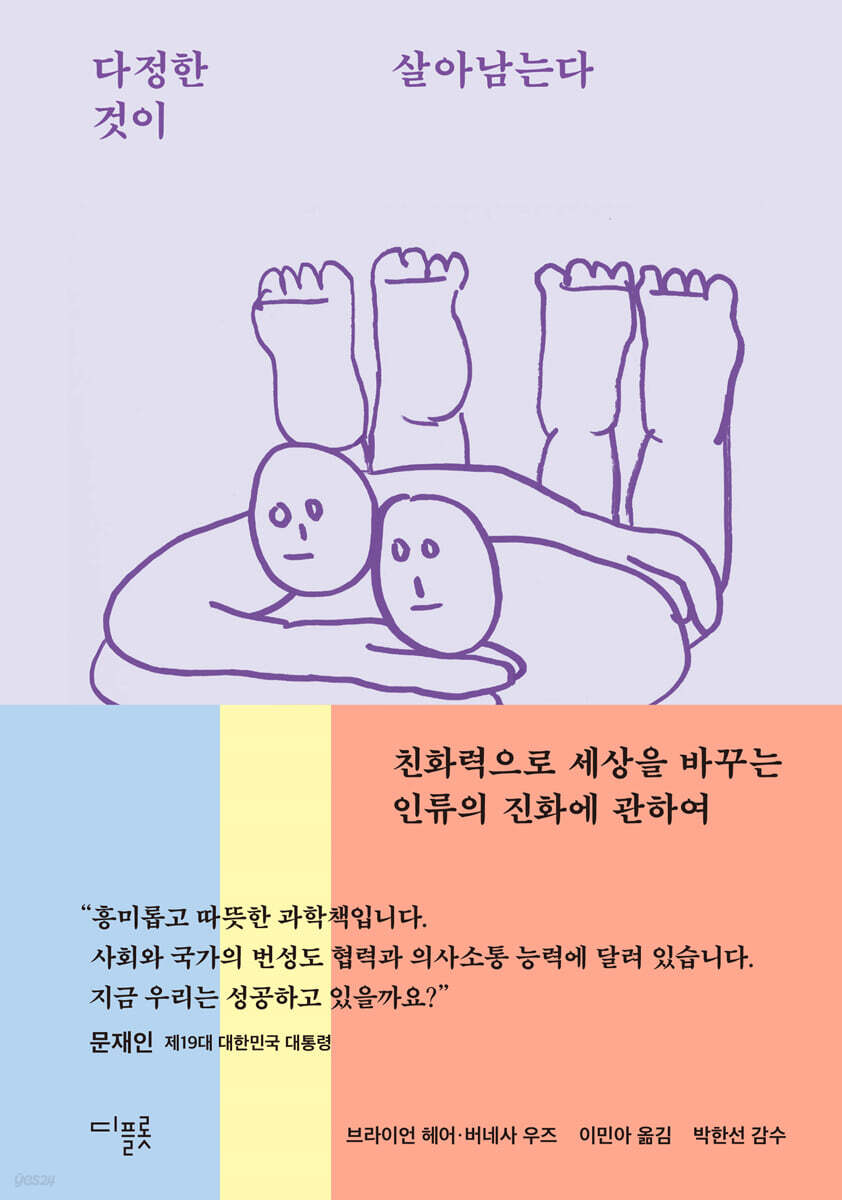

The kind survive

|

Description

Book Introduction

Book of the Year 2021 and 2022, selected by major domestic media outlets Book Seed's Best Books of 2022 The 2022 National Library Competition's Best Books for Librarians Finalist in the Translation Category of the 62nd Korea Publishing Culture Awards The first science book selected by the Kim Young-ha Book Club Books recommended by Moon Jae-in, the 19th President of the Republic of Korea Recommended by Choi Jae-cheon, Kang Yang-gu, Lee Won-young, Eun-yu, Jeong Se-rang, Ha Mi-na, Kim Gyul-ul, Seo Mi-ran, Uhm Ji-hye, Wi Da-hye, and Kim Gyeong-yeong A book that was especially loved by writers and inspired them. A 'perfect book' written by the '21st-century Darwin's successor' at the 'most urgent moment'! As author Jeong Se-rang writes in her recommendation, “Some books come to you at the moment when you most desperately need them.” The Korean edition of "Affection Survives" has been warmly received by Korean readers since its publication in July 2021, and has sold over 100,000 copies, becoming the best-selling book in Korea worldwide. Dr. Brian Hare, who visited Korea in the fall of 2022, called it a "remarkable event" and expressed special gratitude to his kind Korean readers. Although it has been two years since its publication, readers' love for this book remains undiminished, and its message of hope and positivity, "Affection Survives," has become established in Korean society. The '100,000 Copies Special Edition' includes the authors' autographs and handwritten messages. Designer Park Yeon-mi has brought the message of green plants, "affectionate creatures that have successfully evolved and thrived," to life through a new painting by artist Eom Yu-jeong. “While the original Korean version showed the affectionate side of people, this special edition broadens the scope to include the affectionate nature of creatures that have successfully evolved and thrived. The two intersecting stems of the green, round leaves drawn by artist Eom Yu-jeong appear to be greeting each other affectionately. I find comfort in that greeting. “I hope that we can move forward together affectionately, like the branches of a plant that stretch out together.” _Park Yeon-mi, Designer’s Note |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Praise for "The Kind Survive"

Recommended Reading: No life survives without holding hands.

Preface to the Korean edition

Introduction: To survive and evolve

1.

Thoughts about thoughts

2.

The power of affection

3.

Our long-forgotten cousin

4.

domesticated mind

5.

Forever young

6.

To be called a human

7.

uncanny valley

8.

supreme freedom

9.

Best friends

Acknowledgements

Reviewer's Note: Survival of the Righteous

References

Search

Recommended Reading: No life survives without holding hands.

Preface to the Korean edition

Introduction: To survive and evolve

1.

Thoughts about thoughts

2.

The power of affection

3.

Our long-forgotten cousin

4.

domesticated mind

5.

Forever young

6.

To be called a human

7.

uncanny valley

8.

supreme freedom

9.

Best friends

Acknowledgements

Reviewer's Note: Survival of the Righteous

References

Search

Detailed image

.jpg)

Into the book

Biologists are greatly guilty.

For a long time, we have been busy describing nature as a barren place without blood or tears, saying, "An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth."

And they blamed all that sin on Charles Darwin's 'Survival of the fittest'.

'Survival of the fittest' is not an expression originally coined by Darwin.

It was the work of Herbert Spencer, who called himself Darwin's evangelist, but at the urging of Alfred Wallace, Darwin published the fifth edition of The Origin of Species and introduced it as a concept that could replace natural selection, the foundation of his theory.

But Darwin's sins end there.

In "On the Origin of Species," as well as in "The Descent of Man and Sexual Selection" and "The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals," he richly explained with various examples that the way to survive in the struggle for existence is not to dominate everyone around you and become the fittest.

His descendants, on the contrary, confined him within a narrow and simple framework.

This book is a welcome one that completely breaks that mold.

---From "Recommended Reading: No Life Survives Without Holding Hands, p. 5"

Affinity evolved through self-domestication.

Contrary to popular belief, generations of domestication improve sociability without diminishing intelligence.

When an animal is domesticated, many seemingly unrelated factors undergo changes.

The pattern of change in a phenomenon called domestication signs is shown in facial shape, tooth size, and skin color on different body parts.

Changes also occur in hormones, reproductive cycles, and the nervous system.

What we found in our research is that, given certain conditions, self-domestication also improves our ability to cooperate and communicate with others.

---From "Introduction: To Survive and Evolve, p. 31"

Human babies can communicate cooperatively before they say their first words or learn their own names.

Before we understand that when we are happy, others can be sad, and vice versa, before we learn to do bad things and cover them up with lies, or before we understand that we can love someone and they can't love us back, we acquire cooperative communication skills.

It is thanks to this ability that we can communicate emotionally with others.

This ability is a gateway to new social relationships, a cultural world that connects knowledge accumulated over generations.

As Homo sapiens, everything we do begins with this ability.

Like many powerful phenomena, this ability begins in everyday life, when a baby begins to understand the intentions of a parent's gestures.

---From “1 Thoughts on Thoughts, pp. 44-45”

Unlike other experimental models that suggested that domestication occurred only in rare species useful to humans, Belyaev's study suggested that large-scale self-domestication would occur through natural selection among individuals as population densities increased.

This event can occur very rapidly, depending on the strength of selection pressure, population size, and genetic isolation between wild and domesticated populations.

If we could harness human survival by replacing fear with charm, any animal would not only survive but thrive.

---From “The Power of Affection, pp. 83-84”

Because among our ape relatives, only the bonobo is free from the lethal violence that has plagued us.

They don't kill each other.

What humans, who boast exceptional intelligence and intellect, have not been able to achieve, bonobos have achieved.

---From "3 Our Long-Forgotten Cousin, p. 106"

The human self-domestication hypothesis posits that natural selection favored individuals who behaved amicably, enhancing our ability to cooperate and communicate flexibly.

As affiliation increases, cooperative communication skills are strengthened, showing a developmental pattern, and individuals with higher levels of related hormones are believed to become more successful over generations.

---From "4 Domesticated Minds, p. 122"

Most of us feel heartbroken when we see a child suffering.

We want to offer comfort to colleagues who have lost their spouses or bereaved families, and offer a helping hand to relatives who are ill.

We've all become friends with people who were once strangers.

We have the capacity for compassion and empathy, and the ability to be kind to others within our group, traits that are unique to our species and acquired through evolution.

But this kindness is also linked to the cruelty we inflict on one another.

It's the same brain regions that tame our nature and enable cooperative communication, as well as plant the seeds of our worst traits.

---From "6 people, pp. 195-196"

What Goff is pointing out is dehumanization, or more specifically, ape-ification.

When an individual or group is called an ape or compared to an ape, moral exclusion occurs in people's minds, and the individual or group that becomes the target of this apeification becomes a being that does not need to protect basic human rights.

Apeification, rather than prejudice, better explains the racial divide that exists in American society today.

---From "7 Uncanny Valley, p. 218"

We also have the ability to remove someone different from us from the neural networks of our minds when we perceive them as a threat.

Where connection, empathy, and compassion could occur, nothing happens.

When our species-specific neural mechanisms that enable affection, cooperation, and communication shut down, we can commit acts of cruelty.

In this modern society where social media connects us, the tendency toward dehumanization is actually accelerating at a rapid pace.

Large groups that previously expressed prejudice are now engaging in retaliatory dehumanization, and we are quickly moving towards a world where people not only treat each other less than human, but also retaliatory dehumanization of one another.

At a terrifying speed.

---From "7 Uncanny Valley, p. 226"

The American political system is based on the democratic principle that all people, even our worst enemies, deserve to be treated as equals.

We must turn a blind eye to leaders who dehumanize others and empower those who, regardless of party affiliation, insist on practicing humanity toward others.

---From "8 Supreme Freedoms, p. 279"

The friendship and love I shared with Oreo taught me a lesson more valuable than anything else.

Our lives should not be judged by how many enemies we conquer, but by how many friends we make.

That is the hidden secret that allowed our species to survive.

For a long time, we have been busy describing nature as a barren place without blood or tears, saying, "An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth."

And they blamed all that sin on Charles Darwin's 'Survival of the fittest'.

'Survival of the fittest' is not an expression originally coined by Darwin.

It was the work of Herbert Spencer, who called himself Darwin's evangelist, but at the urging of Alfred Wallace, Darwin published the fifth edition of The Origin of Species and introduced it as a concept that could replace natural selection, the foundation of his theory.

But Darwin's sins end there.

In "On the Origin of Species," as well as in "The Descent of Man and Sexual Selection" and "The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals," he richly explained with various examples that the way to survive in the struggle for existence is not to dominate everyone around you and become the fittest.

His descendants, on the contrary, confined him within a narrow and simple framework.

This book is a welcome one that completely breaks that mold.

---From "Recommended Reading: No Life Survives Without Holding Hands, p. 5"

Affinity evolved through self-domestication.

Contrary to popular belief, generations of domestication improve sociability without diminishing intelligence.

When an animal is domesticated, many seemingly unrelated factors undergo changes.

The pattern of change in a phenomenon called domestication signs is shown in facial shape, tooth size, and skin color on different body parts.

Changes also occur in hormones, reproductive cycles, and the nervous system.

What we found in our research is that, given certain conditions, self-domestication also improves our ability to cooperate and communicate with others.

---From "Introduction: To Survive and Evolve, p. 31"

Human babies can communicate cooperatively before they say their first words or learn their own names.

Before we understand that when we are happy, others can be sad, and vice versa, before we learn to do bad things and cover them up with lies, or before we understand that we can love someone and they can't love us back, we acquire cooperative communication skills.

It is thanks to this ability that we can communicate emotionally with others.

This ability is a gateway to new social relationships, a cultural world that connects knowledge accumulated over generations.

As Homo sapiens, everything we do begins with this ability.

Like many powerful phenomena, this ability begins in everyday life, when a baby begins to understand the intentions of a parent's gestures.

---From “1 Thoughts on Thoughts, pp. 44-45”

Unlike other experimental models that suggested that domestication occurred only in rare species useful to humans, Belyaev's study suggested that large-scale self-domestication would occur through natural selection among individuals as population densities increased.

This event can occur very rapidly, depending on the strength of selection pressure, population size, and genetic isolation between wild and domesticated populations.

If we could harness human survival by replacing fear with charm, any animal would not only survive but thrive.

---From “The Power of Affection, pp. 83-84”

Because among our ape relatives, only the bonobo is free from the lethal violence that has plagued us.

They don't kill each other.

What humans, who boast exceptional intelligence and intellect, have not been able to achieve, bonobos have achieved.

---From "3 Our Long-Forgotten Cousin, p. 106"

The human self-domestication hypothesis posits that natural selection favored individuals who behaved amicably, enhancing our ability to cooperate and communicate flexibly.

As affiliation increases, cooperative communication skills are strengthened, showing a developmental pattern, and individuals with higher levels of related hormones are believed to become more successful over generations.

---From "4 Domesticated Minds, p. 122"

Most of us feel heartbroken when we see a child suffering.

We want to offer comfort to colleagues who have lost their spouses or bereaved families, and offer a helping hand to relatives who are ill.

We've all become friends with people who were once strangers.

We have the capacity for compassion and empathy, and the ability to be kind to others within our group, traits that are unique to our species and acquired through evolution.

But this kindness is also linked to the cruelty we inflict on one another.

It's the same brain regions that tame our nature and enable cooperative communication, as well as plant the seeds of our worst traits.

---From "6 people, pp. 195-196"

What Goff is pointing out is dehumanization, or more specifically, ape-ification.

When an individual or group is called an ape or compared to an ape, moral exclusion occurs in people's minds, and the individual or group that becomes the target of this apeification becomes a being that does not need to protect basic human rights.

Apeification, rather than prejudice, better explains the racial divide that exists in American society today.

---From "7 Uncanny Valley, p. 218"

We also have the ability to remove someone different from us from the neural networks of our minds when we perceive them as a threat.

Where connection, empathy, and compassion could occur, nothing happens.

When our species-specific neural mechanisms that enable affection, cooperation, and communication shut down, we can commit acts of cruelty.

In this modern society where social media connects us, the tendency toward dehumanization is actually accelerating at a rapid pace.

Large groups that previously expressed prejudice are now engaging in retaliatory dehumanization, and we are quickly moving towards a world where people not only treat each other less than human, but also retaliatory dehumanization of one another.

At a terrifying speed.

---From "7 Uncanny Valley, p. 226"

The American political system is based on the democratic principle that all people, even our worst enemies, deserve to be treated as equals.

We must turn a blind eye to leaders who dehumanize others and empower those who, regardless of party affiliation, insist on practicing humanity toward others.

---From "8 Supreme Freedoms, p. 279"

The friendship and love I shared with Oreo taught me a lesson more valuable than anything else.

Our lives should not be judged by how many enemies we conquer, but by how many friends we make.

That is the hidden secret that allowed our species to survive.

---From "9 Best Friends, Page 300"

Publisher's Review

The survival of the fittest so far has been wrong.

The winners of evolution were not the fittest, but the kindest.

The evolution and future of Homo sapiens, which thrived by using affection as a weapon.

Exploring the possibility of hope beyond an era of anger and hatred!

While wolves are endangered, how did dogs, descended from the same ancestor, manage to thrive? Why were the affectionate bonobos more successful than the ferocious chimpanzees? Why did Homo sapiens, rather than the physically superior Neanderthals, survive to the end? Brian Hare and Vanessa Woods, the "21st-century Darwinians," offer the following answer: "The affectionate survive."

They challenge the conventional wisdom of 'survival of the fittest', which states that 'the physically fittest survive', and argue that the final survivors were friendly and affectionate individuals. However, they also capture the tendency toward hatred and dehumanization toward outgroups that lies behind friendly relations.

The solution they propose is also affinity based on exchange and cooperation.

Our species survived not by conquering more enemies, but by making more friends.

The one who reads minds survives

“The ideal way to win the game of evolution is to maximize affinity, which allows cooperation to flourish.” (p. 20)

The 'survival of the fittest' that we are all familiar with was not actually an expression invented by Darwin.

Darwin argued that in the struggle for existence, one does not have to be the fittest to survive.

Rather, biologists since Darwin have described nature as a “dreary, heartless place.”

Hair and Woods use the original title of the book, "Survival of the Friendliest," a variation of "Survival of the Fittest," and say that it is not "the fittest" but "the friendliest" that survive.

The essential element for survival they speak of is 'affinity', which is the ability to cooperate and communicate with others who are different from oneself.

This ability is most evident in our own species, Homo sapiens, but Hare also finds it in dogs, whose numbers are increasing every year.

He first conducts a simple hand gesture experiment with his dog, Oreo.

The idea is to place two cups with food hidden on one side and see if Oreo really understands the meaning of the gesture and finds the food when Hair points to the cup with the food.

Surprisingly, Oreo runs quickly and finds food.

After several modified experiments with other dogs, as well as Oreo, Hare concluded that dogs understand the meaning of hand gestures.

When the same experiment was attempted on bonobos and chimpanzees, the friendly bonobos were able to make eye contact with humans, understand the intent of their gaze, and find food, but the unfriendly chimpanzees continued to fail the experiment.

The species that best understands the meaning of these gestures and body language is humans.

Even before they can walk, human babies make eye contact with their parents and understand the intentions of hand and body language.

This is because humans have the ability to read other people's minds, called 'theory of mind'.

This allows our species to “cooperate and communicate with others in the most sophisticated way on Earth.”

By communicating emotionally with others, our species has evolved to regulate emotional responses, develop self-control, and gain an advantage in survival.

Be kind to people you meet for the first time

“For our species to survive and evolve, we must expand our definitions.” (p. 36)

Affection is a trait common to all domesticated species.

Dogs have been domesticated, but wolves have not.

Most people believe that humans intentionally bred wolves to become domesticated dogs, but dogs are a domesticated species themselves.

Dogs that were friendly and not afraid of people survived near hunter-gatherer settlements by eating human excrement, and breeding that occurred only among these friendly dogs resulted in them becoming more friendly animals towards people.

This is evidenced by several signs of domestication (bleaching, floppy or smaller ears, small teeth, docility, smaller brain, more frequent breeding cycles, etc.).

These signs of domestication were also seen in Homo sapiens, the only surviving human species, which means that humans were also domesticated.

Homo sapiens, with their increased affinity, expanded their social networks, achieved technological innovations, and were able to obtain more food through improved technology.

This densely populated population further advanced technology.

But technological innovation alone did not enable Homo sapiens to survive.

Our species has also created a new social category: 'others within the group.'

Even if we have never met before, we recognize people who wear the same uniform or are in the same club as our group.

We consider others who share common social norms as part of the same group and actively help each other.

This affinity toward 'others within the group' creates a group identity and unites others as a 'family'.

In this way, “our species expands the definition of group membership,” a trait not only found in bonobos, which are generally highly inclusive, but also in no other animal.

The Aggression and Hatred Behind Affection

“We are simultaneously the most tolerant and the most ruthless species on Earth.” (p. 32)

Increased affinity toward the in-group reinforces prejudice against out-group members and even leads to exclusion of out-group members.

It's like a dog barking at someone other than its owner.

When an outgroup that poses a threat to one's own group or family appears, the activity in the area of our brain responsible for 'theory of mind' slows down.

When the ability to read others' minds weakens, empathy disappears and it becomes easy to dehumanize others.

In place of friendliness, only aggression and hatred remain.

Hair and Woods cite 'apeification' and 'mutual hostility' as examples of this phenomenon.

Apeification refers to comparing people from other groups to one's own group as 'subhuman apes'.

According to Kteili's research, white people see black people and Asians as being closer to apes than themselves, Hungarians see Roma (Gypsies), and immediately after the attacks, British people see Muslims as being closer to apes than themselves.

Another problem behind affinity is reciprocal hostility.

As dehumanization progresses among groups, 'retaliatory dehumanization' occurs against the out-group that dehumanized the in-group, further exacerbating the conflict between groups.

This is a universal phenomenon that is currently occurring not only across races and nations, but also within a country.

In particular, an alt-right group composed of people with high 'social dominance tendencies' and 'right-wing authoritarian tendencies' has emerged around the world recently. People with social dominance tendencies who believe their in-group is superior and people with right-wing authoritarian tendencies who respond to out-groups with hatred are engaging in even more severe dehumanization based on this mutual hostility.

The future of humanity at the opposite end of polarization

“Our lives should not be judged by how many enemies we conquer, but by how many friends we make.” (p. 300)

This book was written during the Trump era, when hatred fueled his rise to power.

When Trump said Mexico's "border wall is like a zoo fence to keep the beasts out," Democratic Rep. Ilhan Omar retaliated, saying, "The higher the monkey climbs, the more you see its butt."

Weeks after Trump's inauguration, protesters from the radical left-wing group Antifa rallied to protest the right-wing speaker.

The protest, which drew attention by lighting Molotov cocktails and breaking windows, appeared to be a success on the surface.

But according to American political scientist Erica Chenoweth, labeling the other group an outgroup and dehumanizing or engaging in violent protests against that group “doesn’t work.”

As mentioned earlier, according to the 'human self-domestication hypothesis', when members of a group dehumanize an out-group, they induce the worst acts of violence against the other group.

Comparing people to animals or describing them in terms that are repulsive is also the most dangerous form of 'hate speech'.

The 'human self-domestication hypothesis' also suggests a solution to this.

The answer is contact and interaction.

The more frequent the interaction, the more likely it is that the cycle of 'retaliatory dehumanization' that occurs when a member of the in-group is threatened will change to 'reciprocal humanization.'

When alt-right members come into contact with minorities like gays, black prisoners, immigrants, and the homeless, they become more tolerant, and when we see that most Europeans who helped Jews survive World War II had close ties to Jews before the war, contact and exchange can be seen as ways to reduce dehumanization, exclusion, and hatred.

Recently, Korean society seems to be looking at a 'hell map'.

Criticism and dehumanization of non-supporting political parties and groups are severe, and the level of gender conflict is worsening.

Progressive and conservative parties are driving polarization by spewing hateful language.

In the public sphere, only harsh and sharp words of hatred are heard.

It's almost like we're seeing a side of 'survival of the fittest' where everyone is trying to be the best.

The message of self-improvement and self-sufficiency—that I must subdue you to survive—haunts schools and businesses like a ghost.

But now we know.

“Violence breeds violence,” and being consistent in anger is ineffective.

If we are to survive, we must respond with affection.

Meeting, making eye contact, and listening to each other's stories.

Opening up opportunities for interaction and contact without excluding people who are 'different' from me.

Because, as was the case with humans in the past, only the affectionate can survive.

The winners of evolution were not the fittest, but the kindest.

The evolution and future of Homo sapiens, which thrived by using affection as a weapon.

Exploring the possibility of hope beyond an era of anger and hatred!

While wolves are endangered, how did dogs, descended from the same ancestor, manage to thrive? Why were the affectionate bonobos more successful than the ferocious chimpanzees? Why did Homo sapiens, rather than the physically superior Neanderthals, survive to the end? Brian Hare and Vanessa Woods, the "21st-century Darwinians," offer the following answer: "The affectionate survive."

They challenge the conventional wisdom of 'survival of the fittest', which states that 'the physically fittest survive', and argue that the final survivors were friendly and affectionate individuals. However, they also capture the tendency toward hatred and dehumanization toward outgroups that lies behind friendly relations.

The solution they propose is also affinity based on exchange and cooperation.

Our species survived not by conquering more enemies, but by making more friends.

The one who reads minds survives

“The ideal way to win the game of evolution is to maximize affinity, which allows cooperation to flourish.” (p. 20)

The 'survival of the fittest' that we are all familiar with was not actually an expression invented by Darwin.

Darwin argued that in the struggle for existence, one does not have to be the fittest to survive.

Rather, biologists since Darwin have described nature as a “dreary, heartless place.”

Hair and Woods use the original title of the book, "Survival of the Friendliest," a variation of "Survival of the Fittest," and say that it is not "the fittest" but "the friendliest" that survive.

The essential element for survival they speak of is 'affinity', which is the ability to cooperate and communicate with others who are different from oneself.

This ability is most evident in our own species, Homo sapiens, but Hare also finds it in dogs, whose numbers are increasing every year.

He first conducts a simple hand gesture experiment with his dog, Oreo.

The idea is to place two cups with food hidden on one side and see if Oreo really understands the meaning of the gesture and finds the food when Hair points to the cup with the food.

Surprisingly, Oreo runs quickly and finds food.

After several modified experiments with other dogs, as well as Oreo, Hare concluded that dogs understand the meaning of hand gestures.

When the same experiment was attempted on bonobos and chimpanzees, the friendly bonobos were able to make eye contact with humans, understand the intent of their gaze, and find food, but the unfriendly chimpanzees continued to fail the experiment.

The species that best understands the meaning of these gestures and body language is humans.

Even before they can walk, human babies make eye contact with their parents and understand the intentions of hand and body language.

This is because humans have the ability to read other people's minds, called 'theory of mind'.

This allows our species to “cooperate and communicate with others in the most sophisticated way on Earth.”

By communicating emotionally with others, our species has evolved to regulate emotional responses, develop self-control, and gain an advantage in survival.

Be kind to people you meet for the first time

“For our species to survive and evolve, we must expand our definitions.” (p. 36)

Affection is a trait common to all domesticated species.

Dogs have been domesticated, but wolves have not.

Most people believe that humans intentionally bred wolves to become domesticated dogs, but dogs are a domesticated species themselves.

Dogs that were friendly and not afraid of people survived near hunter-gatherer settlements by eating human excrement, and breeding that occurred only among these friendly dogs resulted in them becoming more friendly animals towards people.

This is evidenced by several signs of domestication (bleaching, floppy or smaller ears, small teeth, docility, smaller brain, more frequent breeding cycles, etc.).

These signs of domestication were also seen in Homo sapiens, the only surviving human species, which means that humans were also domesticated.

Homo sapiens, with their increased affinity, expanded their social networks, achieved technological innovations, and were able to obtain more food through improved technology.

This densely populated population further advanced technology.

But technological innovation alone did not enable Homo sapiens to survive.

Our species has also created a new social category: 'others within the group.'

Even if we have never met before, we recognize people who wear the same uniform or are in the same club as our group.

We consider others who share common social norms as part of the same group and actively help each other.

This affinity toward 'others within the group' creates a group identity and unites others as a 'family'.

In this way, “our species expands the definition of group membership,” a trait not only found in bonobos, which are generally highly inclusive, but also in no other animal.

The Aggression and Hatred Behind Affection

“We are simultaneously the most tolerant and the most ruthless species on Earth.” (p. 32)

Increased affinity toward the in-group reinforces prejudice against out-group members and even leads to exclusion of out-group members.

It's like a dog barking at someone other than its owner.

When an outgroup that poses a threat to one's own group or family appears, the activity in the area of our brain responsible for 'theory of mind' slows down.

When the ability to read others' minds weakens, empathy disappears and it becomes easy to dehumanize others.

In place of friendliness, only aggression and hatred remain.

Hair and Woods cite 'apeification' and 'mutual hostility' as examples of this phenomenon.

Apeification refers to comparing people from other groups to one's own group as 'subhuman apes'.

According to Kteili's research, white people see black people and Asians as being closer to apes than themselves, Hungarians see Roma (Gypsies), and immediately after the attacks, British people see Muslims as being closer to apes than themselves.

Another problem behind affinity is reciprocal hostility.

As dehumanization progresses among groups, 'retaliatory dehumanization' occurs against the out-group that dehumanized the in-group, further exacerbating the conflict between groups.

This is a universal phenomenon that is currently occurring not only across races and nations, but also within a country.

In particular, an alt-right group composed of people with high 'social dominance tendencies' and 'right-wing authoritarian tendencies' has emerged around the world recently. People with social dominance tendencies who believe their in-group is superior and people with right-wing authoritarian tendencies who respond to out-groups with hatred are engaging in even more severe dehumanization based on this mutual hostility.

The future of humanity at the opposite end of polarization

“Our lives should not be judged by how many enemies we conquer, but by how many friends we make.” (p. 300)

This book was written during the Trump era, when hatred fueled his rise to power.

When Trump said Mexico's "border wall is like a zoo fence to keep the beasts out," Democratic Rep. Ilhan Omar retaliated, saying, "The higher the monkey climbs, the more you see its butt."

Weeks after Trump's inauguration, protesters from the radical left-wing group Antifa rallied to protest the right-wing speaker.

The protest, which drew attention by lighting Molotov cocktails and breaking windows, appeared to be a success on the surface.

But according to American political scientist Erica Chenoweth, labeling the other group an outgroup and dehumanizing or engaging in violent protests against that group “doesn’t work.”

As mentioned earlier, according to the 'human self-domestication hypothesis', when members of a group dehumanize an out-group, they induce the worst acts of violence against the other group.

Comparing people to animals or describing them in terms that are repulsive is also the most dangerous form of 'hate speech'.

The 'human self-domestication hypothesis' also suggests a solution to this.

The answer is contact and interaction.

The more frequent the interaction, the more likely it is that the cycle of 'retaliatory dehumanization' that occurs when a member of the in-group is threatened will change to 'reciprocal humanization.'

When alt-right members come into contact with minorities like gays, black prisoners, immigrants, and the homeless, they become more tolerant, and when we see that most Europeans who helped Jews survive World War II had close ties to Jews before the war, contact and exchange can be seen as ways to reduce dehumanization, exclusion, and hatred.

Recently, Korean society seems to be looking at a 'hell map'.

Criticism and dehumanization of non-supporting political parties and groups are severe, and the level of gender conflict is worsening.

Progressive and conservative parties are driving polarization by spewing hateful language.

In the public sphere, only harsh and sharp words of hatred are heard.

It's almost like we're seeing a side of 'survival of the fittest' where everyone is trying to be the best.

The message of self-improvement and self-sufficiency—that I must subdue you to survive—haunts schools and businesses like a ghost.

But now we know.

“Violence breeds violence,” and being consistent in anger is ineffective.

If we are to survive, we must respond with affection.

Meeting, making eye contact, and listening to each other's stories.

Opening up opportunities for interaction and contact without excluding people who are 'different' from me.

Because, as was the case with humans in the past, only the affectionate can survive.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: July 26, 2021

- Page count, weight, size: 396 pages | 548g | 135*195*30mm

- ISBN13: 9791197413025

- ISBN10: 1197413022

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)