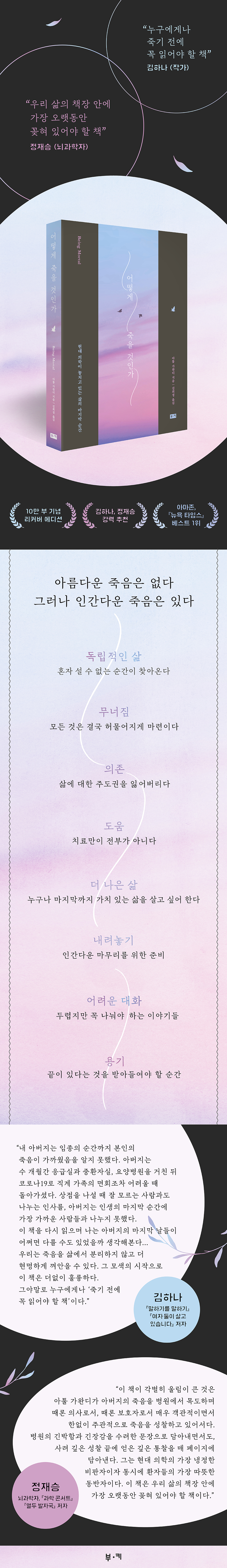

How to Die (Recovery Edition)

|

Description

Book Introduction

Atul Gawande, a world-renowned thinker,

Confessing human dignity and the limitations of medicine in the face of death

In developed countries today, the rectangularization of the population structure is progressing rapidly.

In the United States, the number of people aged 50 and over is currently similar to the number of people aged 5 and under, and in 30 years, the number of people aged 80 and over will be equal to the number of people aged 5 and under.

Rapid aging is also taking place in Korea.

The population aged 65 and over is expected to increase to 24.3% in 2030 and 40.1% in 2060.

The problem raised by Atul Gawande is in line with this social reality.

Modern medicine has focused on prolonging life and aggressively treating disease.

However, the truth is that little attention is being paid to the longer lifespans of old age and the process of death from old age and disease.

Everyone wants to live with dignity and humanity until the very end and then face death.

How can we achieve this? The author suggests that we must begin by accepting the reality that we will ultimately die.

Only when we acknowledge those limitations can we prepare for a humane ending.

Confessing human dignity and the limitations of medicine in the face of death

In developed countries today, the rectangularization of the population structure is progressing rapidly.

In the United States, the number of people aged 50 and over is currently similar to the number of people aged 5 and under, and in 30 years, the number of people aged 80 and over will be equal to the number of people aged 5 and under.

Rapid aging is also taking place in Korea.

The population aged 65 and over is expected to increase to 24.3% in 2030 and 40.1% in 2060.

The problem raised by Atul Gawande is in line with this social reality.

Modern medicine has focused on prolonging life and aggressively treating disease.

However, the truth is that little attention is being paid to the longer lifespans of old age and the process of death from old age and disease.

Everyone wants to live with dignity and humanity until the very end and then face death.

How can we achieve this? The author suggests that we must begin by accepting the reality that we will ultimately die.

Only when we acknowledge those limitations can we prepare for a humane ending.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommendation

introduction

Chapter 1: Independent Living

There comes a time when you can't stand alone.

Chapter 2 Collapse

Everything is destined to crumble

Chapter 3 Dependence

Lose control over your life

Chapter 4 Help

Treatment isn't everything

Chapter 5 A Better Life

Everyone wants to live a worthwhile life until the end.

Chapter 6 Putting it down

Preparing for a humane ending

Chapter 7 Difficult Conversations

Stories that are scary but must be shared

Chapter 8 Courage

The moment when you have to accept that there is an end

Epilogue

Part 1: The Birth of the SNS Kingdom

introduction

Chapter 1: Independent Living

There comes a time when you can't stand alone.

Chapter 2 Collapse

Everything is destined to crumble

Chapter 3 Dependence

Lose control over your life

Chapter 4 Help

Treatment isn't everything

Chapter 5 A Better Life

Everyone wants to live a worthwhile life until the end.

Chapter 6 Putting it down

Preparing for a humane ending

Chapter 7 Difficult Conversations

Stories that are scary but must be shared

Chapter 8 Courage

The moment when you have to accept that there is an end

Epilogue

Part 1: The Birth of the SNS Kingdom

Detailed image

Into the book

Lazarov said with a disapproving tone.

“So you’re giving up on me? I’ll try everything I can.” After getting Lazarov’s signature, I left the hospital room, and his son followed me and grabbed me.

When his mother died on a ventilator in the intensive care unit, his father said he would not die like that.

But now, he was being so stubborn, saying, 'I'll do everything I can.'

At the time, I believed that Lazarov's choice was wrong, and I still believe that.

Not because of the risks of the surgery, but because even if he did, there was no chance of him getting back the life he wanted.

It was not a surgery that could restore the life I had enjoyed before my illness worsened, such as my ability to have bowel movements or my vitality.

What he pursued, risking a long and terrible death, was nothing more than an illusion.

And in the end, he met such a death.

---From the "Preface"

Soon after, Grandma started falling more frequently.

Although no bones were broken, the family couldn't help but worry.

So Jim took the natural step that all families do today.

I took my grandmother to the hospital.

After running some tests, the doctor diagnosed that my grandmother had weak bones and recommended taking calcium supplements.

He also adjusted the dosage of her usual medications and prescribed several new ones.

But in reality, he probably didn't know what to do.

Because it was not a problem that could be fixed by a doctor.

Grandma Alice had trouble keeping her balance and sometimes had memory lapses.

It was clear that the problem would become more and more serious.

It seemed that Grandma didn't have much time left to continue living independently.

But as a doctor, I couldn't give you any direction or advice.

---From "Independent Life"

Grandma Alice lost both her privacy and control over her life.

Most of the time I was wearing hospital gowns.

When the staff woke me up, I got up, when they bathed me, I got dressed, and when they told me to eat, I ate.

Also, I had to share a room with whomever the staff assigned me.

Several roommates were chosen regardless of Grandma's wishes.

All of them had cognitive impairment.

Some people were too quiet, others couldn't sleep at night.

Grandma felt like she was locked up.

It felt like I was locked in prison for the crime of being old.

---From "Dependence"

Grandpa Lou looked at Shelly with pleading eyes.

She seemed to know what her father was thinking.

'Can't you just quit your job and stay by my side?' The thought stabbed Shelly in the heart like a knife.

Shelly, with tears in her eyes, said it had become difficult, both emotionally and financially, to care for her father adequately.

Grandpa Lou reluctantly agreed to accompany Shelly on a tour of several facilities.

It seemed impossible for anyone to live happily as they grew older and weaker.

---From "Help"

Medicine focuses on a very small area.

Medical professionals focus on restoring physical health, not maintaining the mind and soul.

And yet, we? And this is precisely where the painful paradox arises? We have entrusted the power to decide how we will live in the final stages of life to medical professionals.

For over half a century, the trials of disease, aging, and death have been of medical interest.

It was a kind of social engineering experiment, entrusting our fate to those who value technical expertise more than a deep understanding of human needs.

The experiment ended in failure.

---From "A Better Life"

I asked Dr. Mark what he hopes to accomplish for patients with terminal lung cancer when he first meets them.

“I think I can somehow get by for a year or two,” he said.

“That’s the expectation I have.

For patients like Sarah, if you're really lucky, you'll only get three or four years." But that's not what patients want to hear.

“Patients come thinking 10 to 20 years ahead.

No matter what patient I meet, I hear the same story.

In fact, if I were in their shoes, I would have done the same thing.”

---From "Putting It Down"

As soon as the palliative care team arrived and administered a small dose of morphine, Sarah's breathing immediately became easier.

As Sarah's suffering lessened, her family suddenly realized they no longer wanted to torment her.

By the next morning, the family was now trying to dissuade the medical staff.

“The medical team was trying to catheterize Sarah and do this and that,” her mother, Dawn, told me.

“That’s what I said.

'No, don't do anything to her.' I thought it was okay to wet the bed.

The medical staff also tried to do various tests, such as measuring blood pressure and blood sugar.

But now I'm no longer interested in things like test results.

“I went to the head nurse and told her to stop everything now.”

---From "Putting It Down"

As his quadriplegia progressed, it would soon take away the things my father held most dear.

If quadriplegia occurs, 24-hour nursing care, oxygen inhalation, and feeding tubes will be required.

I told him that my father didn't seem to want that.

“Absolutely not.

“It’s better to just die,” was my father’s answer.

That day, I asked my father the most difficult questions of my life.

I remember asking each question with great fear.

I don't know what I was afraid of.

It may have been my father or mother's anger, or depression, or perhaps the fear that by asking such a question I might be letting them down.

But after talking, we felt relieved and something became clear.

---From "Difficult Conversations"

My father just kept watching us as we dried him with a wet towel and put on a new shirt.

“Are you sick?” “No.” My father gestured for me to get up.

We put my father in a wheelchair and pushed him to the window overlooking the backyard.

It was a beautiful summer day, full of flowers and trees.

After a while we pushed Father to the dinner table.

My father ate mango, papaya, yogurt, and medicine.

Although his breathing returned to normal, his father remained silent, lost in thought.

“What are you thinking?” I asked.

“I’m thinking about how to avoid prolonging the process until death.

“This, this food is making it longer.” My mother didn’t want to hear that.

“We love taking care of you, Ram.

“Because I love you.” My father shook his head.

“It’s hard, isn’t it?” said my sister.

“Yeah, it’s hard.” “If you could sleep all night, would you want to?” I asked.

“Yes.” “Don’t you want to stay awake? Don’t you want to feel us by your side, to be with us like this?” asked the mother.

Father was silent for a while.

We waited.

“I don’t want to go through something like this.”

“So you’re giving up on me? I’ll try everything I can.” After getting Lazarov’s signature, I left the hospital room, and his son followed me and grabbed me.

When his mother died on a ventilator in the intensive care unit, his father said he would not die like that.

But now, he was being so stubborn, saying, 'I'll do everything I can.'

At the time, I believed that Lazarov's choice was wrong, and I still believe that.

Not because of the risks of the surgery, but because even if he did, there was no chance of him getting back the life he wanted.

It was not a surgery that could restore the life I had enjoyed before my illness worsened, such as my ability to have bowel movements or my vitality.

What he pursued, risking a long and terrible death, was nothing more than an illusion.

And in the end, he met such a death.

---From the "Preface"

Soon after, Grandma started falling more frequently.

Although no bones were broken, the family couldn't help but worry.

So Jim took the natural step that all families do today.

I took my grandmother to the hospital.

After running some tests, the doctor diagnosed that my grandmother had weak bones and recommended taking calcium supplements.

He also adjusted the dosage of her usual medications and prescribed several new ones.

But in reality, he probably didn't know what to do.

Because it was not a problem that could be fixed by a doctor.

Grandma Alice had trouble keeping her balance and sometimes had memory lapses.

It was clear that the problem would become more and more serious.

It seemed that Grandma didn't have much time left to continue living independently.

But as a doctor, I couldn't give you any direction or advice.

---From "Independent Life"

Grandma Alice lost both her privacy and control over her life.

Most of the time I was wearing hospital gowns.

When the staff woke me up, I got up, when they bathed me, I got dressed, and when they told me to eat, I ate.

Also, I had to share a room with whomever the staff assigned me.

Several roommates were chosen regardless of Grandma's wishes.

All of them had cognitive impairment.

Some people were too quiet, others couldn't sleep at night.

Grandma felt like she was locked up.

It felt like I was locked in prison for the crime of being old.

---From "Dependence"

Grandpa Lou looked at Shelly with pleading eyes.

She seemed to know what her father was thinking.

'Can't you just quit your job and stay by my side?' The thought stabbed Shelly in the heart like a knife.

Shelly, with tears in her eyes, said it had become difficult, both emotionally and financially, to care for her father adequately.

Grandpa Lou reluctantly agreed to accompany Shelly on a tour of several facilities.

It seemed impossible for anyone to live happily as they grew older and weaker.

---From "Help"

Medicine focuses on a very small area.

Medical professionals focus on restoring physical health, not maintaining the mind and soul.

And yet, we? And this is precisely where the painful paradox arises? We have entrusted the power to decide how we will live in the final stages of life to medical professionals.

For over half a century, the trials of disease, aging, and death have been of medical interest.

It was a kind of social engineering experiment, entrusting our fate to those who value technical expertise more than a deep understanding of human needs.

The experiment ended in failure.

---From "A Better Life"

I asked Dr. Mark what he hopes to accomplish for patients with terminal lung cancer when he first meets them.

“I think I can somehow get by for a year or two,” he said.

“That’s the expectation I have.

For patients like Sarah, if you're really lucky, you'll only get three or four years." But that's not what patients want to hear.

“Patients come thinking 10 to 20 years ahead.

No matter what patient I meet, I hear the same story.

In fact, if I were in their shoes, I would have done the same thing.”

---From "Putting It Down"

As soon as the palliative care team arrived and administered a small dose of morphine, Sarah's breathing immediately became easier.

As Sarah's suffering lessened, her family suddenly realized they no longer wanted to torment her.

By the next morning, the family was now trying to dissuade the medical staff.

“The medical team was trying to catheterize Sarah and do this and that,” her mother, Dawn, told me.

“That’s what I said.

'No, don't do anything to her.' I thought it was okay to wet the bed.

The medical staff also tried to do various tests, such as measuring blood pressure and blood sugar.

But now I'm no longer interested in things like test results.

“I went to the head nurse and told her to stop everything now.”

---From "Putting It Down"

As his quadriplegia progressed, it would soon take away the things my father held most dear.

If quadriplegia occurs, 24-hour nursing care, oxygen inhalation, and feeding tubes will be required.

I told him that my father didn't seem to want that.

“Absolutely not.

“It’s better to just die,” was my father’s answer.

That day, I asked my father the most difficult questions of my life.

I remember asking each question with great fear.

I don't know what I was afraid of.

It may have been my father or mother's anger, or depression, or perhaps the fear that by asking such a question I might be letting them down.

But after talking, we felt relieved and something became clear.

---From "Difficult Conversations"

My father just kept watching us as we dried him with a wet towel and put on a new shirt.

“Are you sick?” “No.” My father gestured for me to get up.

We put my father in a wheelchair and pushed him to the window overlooking the backyard.

It was a beautiful summer day, full of flowers and trees.

After a while we pushed Father to the dinner table.

My father ate mango, papaya, yogurt, and medicine.

Although his breathing returned to normal, his father remained silent, lost in thought.

“What are you thinking?” I asked.

“I’m thinking about how to avoid prolonging the process until death.

“This, this food is making it longer.” My mother didn’t want to hear that.

“We love taking care of you, Ram.

“Because I love you.” My father shook his head.

“It’s hard, isn’t it?” said my sister.

“Yeah, it’s hard.” “If you could sleep all night, would you want to?” I asked.

“Yes.” “Don’t you want to stay awake? Don’t you want to feel us by your side, to be with us like this?” asked the mother.

Father was silent for a while.

We waited.

“I don’t want to go through something like this.”

---From "Courage"

Publisher's Review

* 100,000 copies sold commemorative recover edition

* [New York Times], Amazon #1 bestseller

* Strongly recommended by Kim Ha-na and Jeong Jae-seung

“So you’re giving up on me?

“We have to try everything we can.”

Lazarov said with a disapproving tone.

“So you’re giving up on me? I’ll try everything I can.” After getting Lazarov’s signature, I left the hospital room, and his son followed me and grabbed me.

When his mother died on a ventilator in the intensive care unit, his father said he would not die like that.

But now, he was being so stubborn, saying, 'I'll do everything I can.'

At the time, I believed that Lazarov's choice was wrong, and I still believe that.

Not because of the risks of the surgery, but because even if he did, there was no chance of him getting back the life he wanted.

It was not a surgery that could restore the life I had enjoyed before my illness worsened, such as my ability to have bowel movements or my vitality.

What he pursued, risking a long and terrible death, was nothing more than an illusion.

And in the end, he met such a death.

In the intensive care unit, he developed respiratory failure, a systemic infection, blood clots from immobility, and bleeding from the blood thinners he was given to treat them.

We were falling behind every day.

Eventually we had no choice but to admit that he was dying.

On the 14th day after surgery, his son told the medical staff to stop all of this.

_ Main text, pages 13-14

All living things die someday.

Humans are no exception.

This is not at all surprising or new.

But sometimes we forget.

The truth that in the end, you have no choice but to die.

This is partly due to the fact that advances in medicine and public health have led to a dramatic increase in life expectancy.

Today, we dream of living as long as possible, and modern medicine is focusing almost all of its capabilities on realizing this 'dream of life extension.'

Medical treatments such as highly technical surgical operations, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy are also in line with efforts to postpone death and prolong life.

But despite all that effort, there is one truth that cannot be avoided.

In the end, death will win.

The problem awareness of Atul Gawande, the author of this book, begins at that very point.

As the original title, 'Being Mortal', suggests, it asks why we must fight this horrific and painful medical battle if we are beings who must die someday.

Besides, in that fight we have more to lose than to gain.

His body is destroyed, his mind becomes confused, and he dies in a cold hospital room without even being able to say a proper goodbye to his family.

In return for all that sacrifice, all we get is a few months or a year or two of extended life.

What's more important is that there's nothing we can do with the little time we gain for the 'rest of our lives'.

All I can do is struggle through harsh treatment and the pain that comes with it.

So, does this mean we have no other options today when we age or die from a fatal disease? The author argues otherwise.

Death itself is never beautiful, but there is a way to die humanely.

“Isn’t this a home?

“Please take me home.”

When Wilson was nineteen, his mother, Jessie, suffered a massive stroke.

At that time, Jessie was only fifty-five years old.

The stroke left her completely paralyzed on one side of her body, unable to walk, stand, or lift her arms.

Also, one side of his face drooped and his speech became slurred.

Although his intelligence and cognitive abilities were unaffected, he was unable to wash, cook, use the toilet, or do laundry on his own, let alone go out to earn money.

She needed help.

However, Wilson, who was attending college, had no income and was sharing a small apartment with a roommate, so he had no way to care for his mother.

Although I had siblings, my circumstances were similar.

The only place I could leave my mother was a nursing home.

Wilson chose a location near his university.

It was a safe and friendly place.

But the mother kept asking for it every time she saw her daughter.

“Take me home.” _ Page 142

There will inevitably come a moment when you can no longer stand alone.

As the body and mind gradually decline, a person reaches a state where he or she can no longer live independently.

Modern medicine and health systems have attempted to address this problem in two ways.

One is to focus on safely housing the elderly by creating protective facilities called 'nursing homes', and the other is to focus on aggressively treating various diseases that people face in old age.

On the surface, there doesn't seem to be any major problem with this method.

Especially from the children's perspective, it is quite reassuring to know that there is a place where their elderly parents can be safely protected, and that medicine will do its best to treat any illness.

But nursing homes and aggressive treatment have common problems.

The point is that it does not include consideration of ‘quality of life’.

In the case of a 'nursing home', it may seem like the best option for someone who is too weak to care for themselves.

However, this standardized facility has a fatal weakness: it takes away the self-determination and autonomy that we can have as 'a person.'

Because we focus solely on rules and safety, considerations for individual lives often take a backseat.

Because of this, many elderly people admitted to facilities fall into feelings of helplessness and depression. (Main text, pp. 113-124)

The author points out that while 'family and home' might be the most promising alternative to this, this is realistically impossible today.

That doesn't mean there are no alternatives.

The authors explain that ongoing experiments are being conducted to find ways to care for older people in a way that provides them with the assistance they need without sacrificing their quality of life.

For example, 'assisted living', first introduced by Karen Brown Wilson, is a concept of a facility that provides the same assistance as a traditional nursing home while guaranteeing 'independent living'.

You have a lockable door, your own furniture, the ability to control the temperature and lighting in your room, and the right to sleep when you want and not have to do anything you don't want to do.

It may seem simple, but these small changes can make a huge difference in the quality of life seniors experience.

There are also experiments to transform existing nursing homes.

We bring in plants and animals into the nursing home, and we also work with nearby schools to instill vitality in the children.

A prime example is Bill Thomas' experiment at Chase Memorial Nursing Home.

He conducted experiments in which he brought dogs, cats, birds, plants, and children into the nursing home, and the results were astonishing. (Pages 141-149)

Chase Nursing Home residents were found to be taking only half as many prescription medications as comparison group residents.

Prescriptions of psychotropic medications for anxiety symptoms, such as Haldol, have decreased in particular.

The cost of purchasing the drug was only 38% of that of the comparison group.

Mortality rates also decreased by 15%.

_ Page 193 of the text

There were concerns that Bill Thomas' experiment would compromise the health and safety of nursing home residents, but the results were quite the opposite.

But the author says that the fact that the results are surprising in numbers is not the point.

What's more important is that older people who have reached the final stage do not have to give up their quality of life.

There is a reason why the author deals with the topic of 'death' and focuses on the issue of quality of life in old age.

This is because we are arguing that we should not focus solely on postponing death, but rather on how to live the ‘remaining life.’

A humane ending begins at that very point.

In that sense, 'how to die' can be said to be directly connected to 'how to live the rest of one's life.'

If so, the aggressive treatment of modern medicine brings even bigger problems.

“No, don’t do anything to him.

“Please stop all this!”

“The medical team was trying to catheterize Sarah and do this and that,” her mother, Dawn, told me.

“That’s what I said.

'No, don't do anything to her.' I thought it was okay to wet the bed.

The medical staff also tried to do various tests, such as measuring blood pressure and blood sugar.

But now I'm no longer interested in things like test results.

“I went to the head nurse and told her to stop everything now.”

All the things we'd done to Sarah over the past three months—numerous scans, tests, radiation treatments, chemotherapy—had done nothing to help, and in fact, had only made her worse.

If she had done nothing, Sarah might have lived longer.

At least she found peace, if only for the very last moment.

_ Page 289 of the text

Ventilators, feeding tubes, CPR, intensive care units… .

This is a common experience for people facing the end of their lives today.

And that's not all.

Before entering the intensive care unit, you will have to endure an even more gruesome process.

Chemotherapy and radiation treatments are destroying the body and destroying the mind.

Severe pain, nausea, and delirium make it impossible to live a normal life.

The author says that it has only been about 10 years since experiments began to make the process of dying into a medical experience.

And he rebukes them, saying that this experiment appears to be ending in failure.

The reason we call it a failure is because we gain almost nothing from this 'fight'.

They just keep fighting brutally to gain a little more time.

Modern medicine has been fighting what is essentially an 'unsolvable problem'.

It is the fact that the human body is destined to eventually collapse.

The author, who is also a doctor himself, first calls for change in the medical community.

To stop this exhausting medical battle, a change in consciousness within the medical community, which should be playing a guiding role, is necessary first.

There are two most important prerequisites for this.

One is interest in 'geriatrics'.

Rather than focusing solely on addressing individual issues like arthritis, diabetes, and heart disease, we need to consider and manage life holistically in later life (pp. 62-65).

Second, there needs to be a change in the way we make decisions with patients.

Rather than unilaterally suggesting solutions or listing various pieces of information, doctors need to adopt an 'interpretive' attitude.

The role is to listen to what patients want, interpret it, and guide them on what steps can be taken to achieve what they want.

It allows patients to make their own decisions about the final stages of their lives. (Pages 306-309)

The reason an interpretive attitude is important is that what terminally ill patients want is not simply to prolong life.

Patients often cling to treatment because they don't know what they want or how to get it done.

In fact, when I talk to patients, I find that they are more concerned with reducing their suffering, maintaining their dignity in life, catching up on unfinished business, and strengthening their relationships with their families and others.

If you want to prolong your life, it is only because you want to realize the values of everyday life.

I want to complete my own life story in this world during the time I have left.

No patient wants to blindly prolong life if there is a risk that he or she will not be able to realize greater value.

“Atul, I am afraid.

But I would rather die than live like that.”

As his quadriplegia progressed, it would soon take away the things my father held most dear.

If quadriplegia occurs, 24-hour nursing care, oxygen inhalation, and feeding tubes will be required.

I told him that my father didn't seem to want that.

“Absolutely not.

“It’s better to just die,” was my father’s answer.

That day, I asked my father the most difficult questions of my life.

I remember asking each question with great fear.

I don't know what I was afraid of.

It may have been my father or mother's anger, or depression, or perhaps the fear that by asking such a question I might be letting them down.

But after talking, we felt relieved and something became clear.

_ Page 324 of the text

Beyond a shift in medical consciousness, what is required of us ourselves? A shift in mindset, from focusing on prolonging life to reflecting on what truly matters to us.

The most important thing to do for this is to have a 'conversation' about death and the final life.

Because it involves the lives of loved ones, it can be a difficult conversation to face, but the benefits of these "difficult conversations" are numerous.

The author confirms through a conversation with his father, who has a malignant tumor, that he would rather choose death if his father were to reach a point where he was "unable to communicate with people" (pp. 322-324), and palliative care specialist Susan Block's father says that it would be bearable if he could "watch football while eating chocolate ice cream" (pp. 280-281). As a result, this conversation plays a decisive role in everything from major surgery to death.

It has become a compass that can help patients make the best choices.

The importance of discussing your choices in advance during the final stages of life is demonstrated by a case in La Crosse, Wisconsin.

Since 1991, the region has run a campaign encouraging health care professionals and patients to talk about their wishes at the end of life.

As a result, residents of this region spent only half the time in hospital and spent only half the cost of terminal medical care during their last six weeks of life compared to the national average, and their life expectancy was one year longer than the national average. (Main text, pp. 273-275)

If direct communication between family members is difficult, a hospice counselor may be available to guide the conversation.

When many people think of 'hospice', they think of giving up on life and simply waiting for death, but that is not the case.

Through conversations with hospice nurses, the author explains that hospice is not simply about naturally entrusting everything to someone, but rather a process of choosing where to prioritize life in the present.

The goal is to enable patients to live life to the fullest in the present moment.

The goal is to maintain consciousness for as long as possible, minimize suffering, and allow the patient to spend their final days with dignity. (Page 248) This is the so-called "palliative care" field that has developed over the past several decades.

After all, death is, ironically, a process of life.

It is the work of finishing the story of life.

Death itself doesn't really have much meaning.

It is simply the natural order of things that we must die someday.

Yet, the reason why death is such a special and important event for humans is because it contains the story of each of our lives.

At about 6:10 p.m., the final moment finally arrived.

My father was no longer breathing.

When he finally regained consciousness, the father said he wanted to see his grandchildren.

But the kids weren't there, so I showed them the photos on my iPad instead.

My father opened his eyes wide and smiled brightly.

Then I looked at each and every photo.

Father fell into unconsciousness again.

My breathing would stop for 20 to 30 seconds at a time, repeatedly.

Just when I thought it was over, my breathing started again.

Several hours passed like that.

My mother and younger sister were talking while I was by my father's side, and I was reading a book.

At about 6:10 PM, the final moment finally arrived.

I realized that my father's breathing was holding longer than before.

“I think Dad has stopped,” I said.

We approached our father.

Mother took Father's hand.

We listened in silence.

My father was no longer breathing.

_ Page 393 of the text

The message of Atul Gawande's "How to Die" is simple and clear.

Rather than clinging to meaningless and painful life-prolonging treatment, we should reflect on how we will live our last moments.

But what makes this message even more powerful and heartfelt is that he is telling the story of life on the same level as us.

As a doctor and scholar, he does not seek to teach or instruct the general public.

The fact that he is a 'world-class thinker' selected by a world-renowned magazine is also not important.

Many of the people the author met are people we commonly see around us or are similar to our own families.

They are ordinary people who were factory workers in their youth, nurses, store owners, and those who have raised one or two children, lived their lives to the fullest, and found contentment in the small joys of everyday life.

What they want in the final stages of their lives are also very simple things.

She wants to talk more with her family and friends, be a bridesmaid at a friend's wedding that will be held this weekend (page 359), and give one more piano lesson to her beloved student (page 378). And among these ordinary people's stories, there is also an anecdote about the author's father.

Not only the author himself, but his father and mother were also doctors, but for them too, the last moments of life and death were unavoidable.

But they had the courage to acknowledge their limitations and not turn away from death.

The author says that at least two types of courage are needed in the process of growing old and becoming ill.

One is the courage to accept the reality that life has an end.

It is the courage to seek the truth about what we fear and what we can hope for.

The other is the courage to take action based on the truth we discover.

At this point, we must decide which is more important: our fears or our hopes.

It may be the fear of death that keeps one fighting a hopeless battle against illness and clinging to treatment until the end.

But when we acknowledge that death is not something to be feared, but rather an inevitable fate for all living beings, we begin to see what hope can be had.

That is the hope for life.

This is why death is ultimately the story of life.

* [New York Times], Amazon #1 bestseller

* Strongly recommended by Kim Ha-na and Jeong Jae-seung

“So you’re giving up on me?

“We have to try everything we can.”

Lazarov said with a disapproving tone.

“So you’re giving up on me? I’ll try everything I can.” After getting Lazarov’s signature, I left the hospital room, and his son followed me and grabbed me.

When his mother died on a ventilator in the intensive care unit, his father said he would not die like that.

But now, he was being so stubborn, saying, 'I'll do everything I can.'

At the time, I believed that Lazarov's choice was wrong, and I still believe that.

Not because of the risks of the surgery, but because even if he did, there was no chance of him getting back the life he wanted.

It was not a surgery that could restore the life I had enjoyed before my illness worsened, such as my ability to have bowel movements or my vitality.

What he pursued, risking a long and terrible death, was nothing more than an illusion.

And in the end, he met such a death.

In the intensive care unit, he developed respiratory failure, a systemic infection, blood clots from immobility, and bleeding from the blood thinners he was given to treat them.

We were falling behind every day.

Eventually we had no choice but to admit that he was dying.

On the 14th day after surgery, his son told the medical staff to stop all of this.

_ Main text, pages 13-14

All living things die someday.

Humans are no exception.

This is not at all surprising or new.

But sometimes we forget.

The truth that in the end, you have no choice but to die.

This is partly due to the fact that advances in medicine and public health have led to a dramatic increase in life expectancy.

Today, we dream of living as long as possible, and modern medicine is focusing almost all of its capabilities on realizing this 'dream of life extension.'

Medical treatments such as highly technical surgical operations, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy are also in line with efforts to postpone death and prolong life.

But despite all that effort, there is one truth that cannot be avoided.

In the end, death will win.

The problem awareness of Atul Gawande, the author of this book, begins at that very point.

As the original title, 'Being Mortal', suggests, it asks why we must fight this horrific and painful medical battle if we are beings who must die someday.

Besides, in that fight we have more to lose than to gain.

His body is destroyed, his mind becomes confused, and he dies in a cold hospital room without even being able to say a proper goodbye to his family.

In return for all that sacrifice, all we get is a few months or a year or two of extended life.

What's more important is that there's nothing we can do with the little time we gain for the 'rest of our lives'.

All I can do is struggle through harsh treatment and the pain that comes with it.

So, does this mean we have no other options today when we age or die from a fatal disease? The author argues otherwise.

Death itself is never beautiful, but there is a way to die humanely.

“Isn’t this a home?

“Please take me home.”

When Wilson was nineteen, his mother, Jessie, suffered a massive stroke.

At that time, Jessie was only fifty-five years old.

The stroke left her completely paralyzed on one side of her body, unable to walk, stand, or lift her arms.

Also, one side of his face drooped and his speech became slurred.

Although his intelligence and cognitive abilities were unaffected, he was unable to wash, cook, use the toilet, or do laundry on his own, let alone go out to earn money.

She needed help.

However, Wilson, who was attending college, had no income and was sharing a small apartment with a roommate, so he had no way to care for his mother.

Although I had siblings, my circumstances were similar.

The only place I could leave my mother was a nursing home.

Wilson chose a location near his university.

It was a safe and friendly place.

But the mother kept asking for it every time she saw her daughter.

“Take me home.” _ Page 142

There will inevitably come a moment when you can no longer stand alone.

As the body and mind gradually decline, a person reaches a state where he or she can no longer live independently.

Modern medicine and health systems have attempted to address this problem in two ways.

One is to focus on safely housing the elderly by creating protective facilities called 'nursing homes', and the other is to focus on aggressively treating various diseases that people face in old age.

On the surface, there doesn't seem to be any major problem with this method.

Especially from the children's perspective, it is quite reassuring to know that there is a place where their elderly parents can be safely protected, and that medicine will do its best to treat any illness.

But nursing homes and aggressive treatment have common problems.

The point is that it does not include consideration of ‘quality of life’.

In the case of a 'nursing home', it may seem like the best option for someone who is too weak to care for themselves.

However, this standardized facility has a fatal weakness: it takes away the self-determination and autonomy that we can have as 'a person.'

Because we focus solely on rules and safety, considerations for individual lives often take a backseat.

Because of this, many elderly people admitted to facilities fall into feelings of helplessness and depression. (Main text, pp. 113-124)

The author points out that while 'family and home' might be the most promising alternative to this, this is realistically impossible today.

That doesn't mean there are no alternatives.

The authors explain that ongoing experiments are being conducted to find ways to care for older people in a way that provides them with the assistance they need without sacrificing their quality of life.

For example, 'assisted living', first introduced by Karen Brown Wilson, is a concept of a facility that provides the same assistance as a traditional nursing home while guaranteeing 'independent living'.

You have a lockable door, your own furniture, the ability to control the temperature and lighting in your room, and the right to sleep when you want and not have to do anything you don't want to do.

It may seem simple, but these small changes can make a huge difference in the quality of life seniors experience.

There are also experiments to transform existing nursing homes.

We bring in plants and animals into the nursing home, and we also work with nearby schools to instill vitality in the children.

A prime example is Bill Thomas' experiment at Chase Memorial Nursing Home.

He conducted experiments in which he brought dogs, cats, birds, plants, and children into the nursing home, and the results were astonishing. (Pages 141-149)

Chase Nursing Home residents were found to be taking only half as many prescription medications as comparison group residents.

Prescriptions of psychotropic medications for anxiety symptoms, such as Haldol, have decreased in particular.

The cost of purchasing the drug was only 38% of that of the comparison group.

Mortality rates also decreased by 15%.

_ Page 193 of the text

There were concerns that Bill Thomas' experiment would compromise the health and safety of nursing home residents, but the results were quite the opposite.

But the author says that the fact that the results are surprising in numbers is not the point.

What's more important is that older people who have reached the final stage do not have to give up their quality of life.

There is a reason why the author deals with the topic of 'death' and focuses on the issue of quality of life in old age.

This is because we are arguing that we should not focus solely on postponing death, but rather on how to live the ‘remaining life.’

A humane ending begins at that very point.

In that sense, 'how to die' can be said to be directly connected to 'how to live the rest of one's life.'

If so, the aggressive treatment of modern medicine brings even bigger problems.

“No, don’t do anything to him.

“Please stop all this!”

“The medical team was trying to catheterize Sarah and do this and that,” her mother, Dawn, told me.

“That’s what I said.

'No, don't do anything to her.' I thought it was okay to wet the bed.

The medical staff also tried to do various tests, such as measuring blood pressure and blood sugar.

But now I'm no longer interested in things like test results.

“I went to the head nurse and told her to stop everything now.”

All the things we'd done to Sarah over the past three months—numerous scans, tests, radiation treatments, chemotherapy—had done nothing to help, and in fact, had only made her worse.

If she had done nothing, Sarah might have lived longer.

At least she found peace, if only for the very last moment.

_ Page 289 of the text

Ventilators, feeding tubes, CPR, intensive care units… .

This is a common experience for people facing the end of their lives today.

And that's not all.

Before entering the intensive care unit, you will have to endure an even more gruesome process.

Chemotherapy and radiation treatments are destroying the body and destroying the mind.

Severe pain, nausea, and delirium make it impossible to live a normal life.

The author says that it has only been about 10 years since experiments began to make the process of dying into a medical experience.

And he rebukes them, saying that this experiment appears to be ending in failure.

The reason we call it a failure is because we gain almost nothing from this 'fight'.

They just keep fighting brutally to gain a little more time.

Modern medicine has been fighting what is essentially an 'unsolvable problem'.

It is the fact that the human body is destined to eventually collapse.

The author, who is also a doctor himself, first calls for change in the medical community.

To stop this exhausting medical battle, a change in consciousness within the medical community, which should be playing a guiding role, is necessary first.

There are two most important prerequisites for this.

One is interest in 'geriatrics'.

Rather than focusing solely on addressing individual issues like arthritis, diabetes, and heart disease, we need to consider and manage life holistically in later life (pp. 62-65).

Second, there needs to be a change in the way we make decisions with patients.

Rather than unilaterally suggesting solutions or listing various pieces of information, doctors need to adopt an 'interpretive' attitude.

The role is to listen to what patients want, interpret it, and guide them on what steps can be taken to achieve what they want.

It allows patients to make their own decisions about the final stages of their lives. (Pages 306-309)

The reason an interpretive attitude is important is that what terminally ill patients want is not simply to prolong life.

Patients often cling to treatment because they don't know what they want or how to get it done.

In fact, when I talk to patients, I find that they are more concerned with reducing their suffering, maintaining their dignity in life, catching up on unfinished business, and strengthening their relationships with their families and others.

If you want to prolong your life, it is only because you want to realize the values of everyday life.

I want to complete my own life story in this world during the time I have left.

No patient wants to blindly prolong life if there is a risk that he or she will not be able to realize greater value.

“Atul, I am afraid.

But I would rather die than live like that.”

As his quadriplegia progressed, it would soon take away the things my father held most dear.

If quadriplegia occurs, 24-hour nursing care, oxygen inhalation, and feeding tubes will be required.

I told him that my father didn't seem to want that.

“Absolutely not.

“It’s better to just die,” was my father’s answer.

That day, I asked my father the most difficult questions of my life.

I remember asking each question with great fear.

I don't know what I was afraid of.

It may have been my father or mother's anger, or depression, or perhaps the fear that by asking such a question I might be letting them down.

But after talking, we felt relieved and something became clear.

_ Page 324 of the text

Beyond a shift in medical consciousness, what is required of us ourselves? A shift in mindset, from focusing on prolonging life to reflecting on what truly matters to us.

The most important thing to do for this is to have a 'conversation' about death and the final life.

Because it involves the lives of loved ones, it can be a difficult conversation to face, but the benefits of these "difficult conversations" are numerous.

The author confirms through a conversation with his father, who has a malignant tumor, that he would rather choose death if his father were to reach a point where he was "unable to communicate with people" (pp. 322-324), and palliative care specialist Susan Block's father says that it would be bearable if he could "watch football while eating chocolate ice cream" (pp. 280-281). As a result, this conversation plays a decisive role in everything from major surgery to death.

It has become a compass that can help patients make the best choices.

The importance of discussing your choices in advance during the final stages of life is demonstrated by a case in La Crosse, Wisconsin.

Since 1991, the region has run a campaign encouraging health care professionals and patients to talk about their wishes at the end of life.

As a result, residents of this region spent only half the time in hospital and spent only half the cost of terminal medical care during their last six weeks of life compared to the national average, and their life expectancy was one year longer than the national average. (Main text, pp. 273-275)

If direct communication between family members is difficult, a hospice counselor may be available to guide the conversation.

When many people think of 'hospice', they think of giving up on life and simply waiting for death, but that is not the case.

Through conversations with hospice nurses, the author explains that hospice is not simply about naturally entrusting everything to someone, but rather a process of choosing where to prioritize life in the present.

The goal is to enable patients to live life to the fullest in the present moment.

The goal is to maintain consciousness for as long as possible, minimize suffering, and allow the patient to spend their final days with dignity. (Page 248) This is the so-called "palliative care" field that has developed over the past several decades.

After all, death is, ironically, a process of life.

It is the work of finishing the story of life.

Death itself doesn't really have much meaning.

It is simply the natural order of things that we must die someday.

Yet, the reason why death is such a special and important event for humans is because it contains the story of each of our lives.

At about 6:10 p.m., the final moment finally arrived.

My father was no longer breathing.

When he finally regained consciousness, the father said he wanted to see his grandchildren.

But the kids weren't there, so I showed them the photos on my iPad instead.

My father opened his eyes wide and smiled brightly.

Then I looked at each and every photo.

Father fell into unconsciousness again.

My breathing would stop for 20 to 30 seconds at a time, repeatedly.

Just when I thought it was over, my breathing started again.

Several hours passed like that.

My mother and younger sister were talking while I was by my father's side, and I was reading a book.

At about 6:10 PM, the final moment finally arrived.

I realized that my father's breathing was holding longer than before.

“I think Dad has stopped,” I said.

We approached our father.

Mother took Father's hand.

We listened in silence.

My father was no longer breathing.

_ Page 393 of the text

The message of Atul Gawande's "How to Die" is simple and clear.

Rather than clinging to meaningless and painful life-prolonging treatment, we should reflect on how we will live our last moments.

But what makes this message even more powerful and heartfelt is that he is telling the story of life on the same level as us.

As a doctor and scholar, he does not seek to teach or instruct the general public.

The fact that he is a 'world-class thinker' selected by a world-renowned magazine is also not important.

Many of the people the author met are people we commonly see around us or are similar to our own families.

They are ordinary people who were factory workers in their youth, nurses, store owners, and those who have raised one or two children, lived their lives to the fullest, and found contentment in the small joys of everyday life.

What they want in the final stages of their lives are also very simple things.

She wants to talk more with her family and friends, be a bridesmaid at a friend's wedding that will be held this weekend (page 359), and give one more piano lesson to her beloved student (page 378). And among these ordinary people's stories, there is also an anecdote about the author's father.

Not only the author himself, but his father and mother were also doctors, but for them too, the last moments of life and death were unavoidable.

But they had the courage to acknowledge their limitations and not turn away from death.

The author says that at least two types of courage are needed in the process of growing old and becoming ill.

One is the courage to accept the reality that life has an end.

It is the courage to seek the truth about what we fear and what we can hope for.

The other is the courage to take action based on the truth we discover.

At this point, we must decide which is more important: our fears or our hopes.

It may be the fear of death that keeps one fighting a hopeless battle against illness and clinging to treatment until the end.

But when we acknowledge that death is not something to be feared, but rather an inevitable fate for all living beings, we begin to see what hope can be had.

That is the hope for life.

This is why death is ultimately the story of life.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: February 17, 2022

- Page count, weight, size: 400 pages | 546g | 147*218*30mm

- ISBN13: 9788960519091

- ISBN10: 896051909X

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)