Next Thinking

|

Description

Book Introduction

Recommended by Lee Sedol, Jeong Jae-seung, and Jang Kang-myeong

Cass Sunstein, author of "Nudge," recommends David Dunning, author of "The Dunning-Kruger Effect."

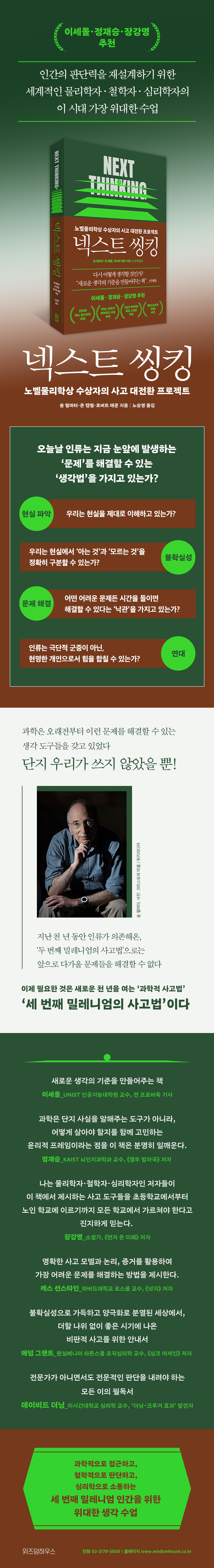

To redesign human judgment

World-renowned physicist, philosopher, and psychologist

The greatest lesson of our time

A book explores the decade-long project to transform human thinking, led by a Nobel Prize winner in physics and world-renowned philosophers and psychologists. Physicist Saul Perlmutter, philosopher John Campbell, and psychologist Robert McCune, who have presented UC Berkeley's renowned "Big Ideas" lecture series, argue that humanity's reliance on intuition alone will not be sufficient to effectively address future challenges. To address today's challenges, such as the proliferation of AI, climate catastrophe, pandemics, fake news, and political polarization, we need a "problem-solving, practical thinking method" that effectively understands the complex world and enables decision-making.

The three authors find the thinking tools for this practical thinking method in 'science'.

The authors call this way of thinking the "Thinking of the Third Millennium," meaning a new "scientific way of thinking" for humanity that will live for the next 1,000 years, from 2001 to 3000.

So what is "scientific thinking"? This book defines "scientific thinking" as a framework of thought that helps us make more effective decisions in a complex world.

In making decisions about real-world issues, 'scientific thinking' requires two procedures.

First, we need to determine what is true.

The ocean of information is vast, but quality and bias vary widely, so it's important to evaluate the reliability of sources and update existing judgments as new evidence emerges.

Second, we need to establish criteria for whose expertise we trust in any given matter.

We cannot make life-or-death decisions like “Should we administer medication to an emergency patient or perform surgery?” by majority vote.

Delegating to the most appropriate expert leads to better decisions.

The authors propose a curriculum that aims to improve the quality of decisions through these procedures and to extend this to decision-making in life and organizations.

And the engine that makes this possible is the various thinking tools that science has accumulated so far.

Cass Sunstein, author of "Nudge," recommends David Dunning, author of "The Dunning-Kruger Effect."

To redesign human judgment

World-renowned physicist, philosopher, and psychologist

The greatest lesson of our time

A book explores the decade-long project to transform human thinking, led by a Nobel Prize winner in physics and world-renowned philosophers and psychologists. Physicist Saul Perlmutter, philosopher John Campbell, and psychologist Robert McCune, who have presented UC Berkeley's renowned "Big Ideas" lecture series, argue that humanity's reliance on intuition alone will not be sufficient to effectively address future challenges. To address today's challenges, such as the proliferation of AI, climate catastrophe, pandemics, fake news, and political polarization, we need a "problem-solving, practical thinking method" that effectively understands the complex world and enables decision-making.

The three authors find the thinking tools for this practical thinking method in 'science'.

The authors call this way of thinking the "Thinking of the Third Millennium," meaning a new "scientific way of thinking" for humanity that will live for the next 1,000 years, from 2001 to 3000.

So what is "scientific thinking"? This book defines "scientific thinking" as a framework of thought that helps us make more effective decisions in a complex world.

In making decisions about real-world issues, 'scientific thinking' requires two procedures.

First, we need to determine what is true.

The ocean of information is vast, but quality and bias vary widely, so it's important to evaluate the reliability of sources and update existing judgments as new evidence emerges.

Second, we need to establish criteria for whose expertise we trust in any given matter.

We cannot make life-or-death decisions like “Should we administer medication to an emergency patient or perform surgery?” by majority vote.

Delegating to the most appropriate expert leads to better decisions.

The authors propose a curriculum that aims to improve the quality of decisions through these procedures and to extend this to decision-making in life and organizations.

And the engine that makes this possible is the various thinking tools that science has accumulated so far.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommendation

Introduction

Part 1: How to Understand Reality

Chapter 1.

We decide something every day

Chapter 2.

Tools and Reality for Understanding the World

Chapter 3.

How can we know cause and effect?

Part 2: Understanding Uncertainty

Chapter 4.

A dramatic shift toward probabilistic thinking

Chapter 5.

Beware of overconfidence

Chapter 6.

Finding the signal in the noise

Chapter 7.

It's not there, but it's visible

Chapter 8.

What errors would you like to avoid more?

Chapter 9.

Two sources of uncertainty

Part 3: How to Overcome Challenges with Optimism

Chapter 10.

scientific optimism

Chapter 11.

Understanding order and the Fermi problem

Part 4: Bridging the Gap Between Experience and Reality

Chapter 12.

How does experience interfere with judgment?

Chapter 13.

Derailment of Science

Chapter 14.

Confirmation bias and blind analysis

Part 5: How to Join Forces Wisely

Chapter 15.

The wisdom and madness of crowds

Chapter 16.

Weaving facts and values

Chapter 17.

If we join forces and think together

Chapter 18.

Trust Reboot for the New Millennium

Acknowledgements

main

Search

Introduction

Part 1: How to Understand Reality

Chapter 1.

We decide something every day

Chapter 2.

Tools and Reality for Understanding the World

Chapter 3.

How can we know cause and effect?

Part 2: Understanding Uncertainty

Chapter 4.

A dramatic shift toward probabilistic thinking

Chapter 5.

Beware of overconfidence

Chapter 6.

Finding the signal in the noise

Chapter 7.

It's not there, but it's visible

Chapter 8.

What errors would you like to avoid more?

Chapter 9.

Two sources of uncertainty

Part 3: How to Overcome Challenges with Optimism

Chapter 10.

scientific optimism

Chapter 11.

Understanding order and the Fermi problem

Part 4: Bridging the Gap Between Experience and Reality

Chapter 12.

How does experience interfere with judgment?

Chapter 13.

Derailment of Science

Chapter 14.

Confirmation bias and blind analysis

Part 5: How to Join Forces Wisely

Chapter 15.

The wisdom and madness of crowds

Chapter 16.

Weaving facts and values

Chapter 17.

If we join forces and think together

Chapter 18.

Trust Reboot for the New Millennium

Acknowledgements

main

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

Scientists have long used these thinking tools as guides, but many of them are not widely used in other fields.

We believe that these tools can and should be used widely.

Whether as individuals, communities, or on a global scale, we believe it has far broader applications and can help us in many more areas and situations, wherever we evaluate information and expertise, make decisions in uncertain situations, and strive to solve problems that affect our lives.

--- From "Introductory Remarks"

Most societies today consider individuals to have the right to make their own decisions that affect them.

But have you ever considered why you should have the power to make the decisions that most affect you? Most societies today assume that individuals have the right to make their own decisions.

But have you ever thought about why you should have a say in the decisions that affect you the most?

Ultimately, all these decisions, from personal to societal, are bets we make.

It's rare that we can be sure we've made the right choice.

This aspect of decision-making can benefit from scientific thinking approaches, particularly the 'probabilistic thinking' technique, which will be discussed in later chapters.

--- From "Chapter 1 We Decide Something Every Day"

Science offers a radically different approach to our approach to contemplating connections with reality, which we know a little about but not everything about.

It allows us to shift from the attitude that we can only handle things we are absolutely certain of to the attitude that we can be more successful if we can handle things with varying degrees of certainty.

Moreover, simply understanding the concept that there are different levels of certainty can be far more effective than trying to get definitive answers from the world.

Because the evidence we have available often does not guarantee the absolute certainty we desire.

The goal, in fact, is not to stake your identity on being right every time (which is impossible), but to develop the ability to roughly judge how certain you are about something.

--- From "Chapter 4: A Dramatic Shift to Probabilistic Thinking"

The history of science is full of stories of overcoming obstacles to arrive at a different approach that satisfies all stakeholders.

In a world saturated with media that makes a living by scaring us with the idea that things are or might be wrong, it's even more important to pay attention to this story.

When we're scared, our natural reaction is to curl up in a ball and try to protect everything we have.

In such a situation, it is extremely difficult or impossible to find a win-win solution to grow the pie.

Scientific optimism offers a different starting point as a cultural antidote to media fear marketing.

--- From "Chapter 10 Scientific Optimism"

When results are produced that challenge current theories, the science that produced those results is subject to much more rigorous scrutiny.

A higher standard of proof is needed to accept that theory.

To use the raft metaphor, a provocative result is like a new log that doesn't fit on the raft in any way.

You don't want to ignore the log just because you can't fit it into the overall story, so you keep it in a bit of isolation for the time being.

Only when enough logs have been collected to build a new and improved raft can work begin.

This is what happened when Einstein proposed the theory of relativity.

This allowed us to consider the concept that space itself could bend.

When you have a strange idea that doesn't make any sense from a general perspective, don't dismiss it just because you have a hard time visualizing how it would work.

--- From "Chapter 13: The Derailment of Science"

There are productive ways to argue about facts.

But can we engage in constructive debate over value conflicts? Can we reach agreement on what to do even when there are heated disagreements over values?

--- From "Chapter 16: Weaving Facts and Values"

Perhaps the defining difference of the third millennium is the fact that everyone is connected and 'in the game', whether they like it or not.

With vast universes of data now readily accessible to everyone, we are forced to figure out what facts to base our decisions on, when to do our own research and when to consult experts, which experts are trustworthy (and on which topics), and when we need a wise guide to integrate our values.

What is TFT? Simply put, (1) it always cooperates when first encountering another player, and (2) thereafter, it unconditionally retaliates against the opponent's last action. Why does TFT succeed? Axelrod defines the characteristics of TFT as "gentlemanly" (always cooperates on the first encounter), "retaliatory" (acts less gentlemanly toward the player who ultimately backed out), and "forgiving" (if the opponent begins to cooperate, it cooperates again).

Like the noble 'unconditional cooperation' participant, TFT performs poorly when first encountering the selfish participant, but never becomes a pushover after that.

However, when they meet 'gentlemanly' participants, they quickly establish beneficial cooperative patterns.

The ability to maintain the belief that a problem can be solved until the problem is solved.

Perhaps we should add a companion concept to our list: 'social optimism.'

This refers to the ability to maintain the belief that most people want to cooperate until a cooperative partner is found and the problem is solved.

With vast universes of data now readily accessible to everyone, we are forced to figure out what facts to base our decisions on, when to do our own research and when to consult experts, which experts are trustworthy (and on which topics), and when we need a wise guide to integrate our values.

But to elaborate on this topic, the challenge isn't just that there's an overwhelming amount of information to sort through.

Another problem is that so many information sources brazenly boast of their completeness and accuracy.

Therefore, we need a 3MT tool that will build a network of credible sources (individuals, experts, institutions, websites) and ultimately establish effective trust relationships that can assess the credibility of conflicting claims.

This is more of a construction process than a filtering exercise.

When we encounter credible information, we believe it not because our preferred political or cultural group believes it and the other side does not, but because those who disagree with us but who question us also believe it.

That is the foundation on which we build our understanding.

We believe that these tools can and should be used widely.

Whether as individuals, communities, or on a global scale, we believe it has far broader applications and can help us in many more areas and situations, wherever we evaluate information and expertise, make decisions in uncertain situations, and strive to solve problems that affect our lives.

--- From "Introductory Remarks"

Most societies today consider individuals to have the right to make their own decisions that affect them.

But have you ever considered why you should have the power to make the decisions that most affect you? Most societies today assume that individuals have the right to make their own decisions.

But have you ever thought about why you should have a say in the decisions that affect you the most?

Ultimately, all these decisions, from personal to societal, are bets we make.

It's rare that we can be sure we've made the right choice.

This aspect of decision-making can benefit from scientific thinking approaches, particularly the 'probabilistic thinking' technique, which will be discussed in later chapters.

--- From "Chapter 1 We Decide Something Every Day"

Science offers a radically different approach to our approach to contemplating connections with reality, which we know a little about but not everything about.

It allows us to shift from the attitude that we can only handle things we are absolutely certain of to the attitude that we can be more successful if we can handle things with varying degrees of certainty.

Moreover, simply understanding the concept that there are different levels of certainty can be far more effective than trying to get definitive answers from the world.

Because the evidence we have available often does not guarantee the absolute certainty we desire.

The goal, in fact, is not to stake your identity on being right every time (which is impossible), but to develop the ability to roughly judge how certain you are about something.

--- From "Chapter 4: A Dramatic Shift to Probabilistic Thinking"

The history of science is full of stories of overcoming obstacles to arrive at a different approach that satisfies all stakeholders.

In a world saturated with media that makes a living by scaring us with the idea that things are or might be wrong, it's even more important to pay attention to this story.

When we're scared, our natural reaction is to curl up in a ball and try to protect everything we have.

In such a situation, it is extremely difficult or impossible to find a win-win solution to grow the pie.

Scientific optimism offers a different starting point as a cultural antidote to media fear marketing.

--- From "Chapter 10 Scientific Optimism"

When results are produced that challenge current theories, the science that produced those results is subject to much more rigorous scrutiny.

A higher standard of proof is needed to accept that theory.

To use the raft metaphor, a provocative result is like a new log that doesn't fit on the raft in any way.

You don't want to ignore the log just because you can't fit it into the overall story, so you keep it in a bit of isolation for the time being.

Only when enough logs have been collected to build a new and improved raft can work begin.

This is what happened when Einstein proposed the theory of relativity.

This allowed us to consider the concept that space itself could bend.

When you have a strange idea that doesn't make any sense from a general perspective, don't dismiss it just because you have a hard time visualizing how it would work.

--- From "Chapter 13: The Derailment of Science"

There are productive ways to argue about facts.

But can we engage in constructive debate over value conflicts? Can we reach agreement on what to do even when there are heated disagreements over values?

--- From "Chapter 16: Weaving Facts and Values"

Perhaps the defining difference of the third millennium is the fact that everyone is connected and 'in the game', whether they like it or not.

With vast universes of data now readily accessible to everyone, we are forced to figure out what facts to base our decisions on, when to do our own research and when to consult experts, which experts are trustworthy (and on which topics), and when we need a wise guide to integrate our values.

What is TFT? Simply put, (1) it always cooperates when first encountering another player, and (2) thereafter, it unconditionally retaliates against the opponent's last action. Why does TFT succeed? Axelrod defines the characteristics of TFT as "gentlemanly" (always cooperates on the first encounter), "retaliatory" (acts less gentlemanly toward the player who ultimately backed out), and "forgiving" (if the opponent begins to cooperate, it cooperates again).

Like the noble 'unconditional cooperation' participant, TFT performs poorly when first encountering the selfish participant, but never becomes a pushover after that.

However, when they meet 'gentlemanly' participants, they quickly establish beneficial cooperative patterns.

The ability to maintain the belief that a problem can be solved until the problem is solved.

Perhaps we should add a companion concept to our list: 'social optimism.'

This refers to the ability to maintain the belief that most people want to cooperate until a cooperative partner is found and the problem is solved.

With vast universes of data now readily accessible to everyone, we are forced to figure out what facts to base our decisions on, when to do our own research and when to consult experts, which experts are trustworthy (and on which topics), and when we need a wise guide to integrate our values.

But to elaborate on this topic, the challenge isn't just that there's an overwhelming amount of information to sort through.

Another problem is that so many information sources brazenly boast of their completeness and accuracy.

Therefore, we need a 3MT tool that will build a network of credible sources (individuals, experts, institutions, websites) and ultimately establish effective trust relationships that can assess the credibility of conflicting claims.

This is more of a construction process than a filtering exercise.

When we encounter credible information, we believe it not because our preferred political or cultural group believes it and the other side does not, but because those who disagree with us but who question us also believe it.

That is the foundation on which we build our understanding.

--- From "Chapter 18: Rebooting Trust for the New Millennium"

Publisher's Review

Science already had the tools of thought to solve problems.

We just didn't write it

For thousands of years, science has been solving the world's mysteries, solving problems, and bringing a better life to humanity.

Scientists have long used these thinking tools to guide their daily lives, but they have not been widely used outside the scientific community.

But wherever we make decisions under uncertain circumstances and solve problems that affect our lives, scientific thinking has broad application and can help us in a vast array of areas and situations.

For example, there is a parental concern such as, “Should I leave my teenage child’s friendships alone so that he or she can develop trust in me and develop autonomy, or should I discipline him or her to prevent him or her from going down the wrong path?”

In times like these, it is more important to observe the child's behavior and determine the threshold at which parents should take action, rather than providing the 'correct answer'.

For example, you can set 'signals' such as 'when you become more late' or 'when your allowance usage suddenly changes', and start conversations or adjust the intensity of your intervention based on those signals.

The important thing is not to jump to conclusions based on a single action, but to observe the signals, make judgments, and adjust the standards little by little through conversation.

In science, this is called "threshold design based on a balance of sensitivity (the power not to miss what is there) and specificity (the power not to falsely filter out what is not there)" (Chapter 8).

In addition, we can change the way we approach problems through practical tools such as 'probabilistic thinking' (Chapter 4) to reduce the risk of decisions, 'distinguishing between signal and noise' (Chapter 6) to increase accuracy by separating meaning from noise in data, and 'Fermi estimation' (Chapter 11) to quickly obtain approximations by breaking down complex reality.

The goal of this book is to connect this scientific approach to the problems of life and work, equipping you with a "real-world problem-solving mindset."

scientific optimism

The 'can-do' spirit that says if you don't give up, you'll eventually solve the problem.

However, to solve problems of social reality beyond the individual level, simply approaching the problem scientifically is not enough.

We need to be optimistic that this problem can be solved someday.

Because most of the problems we face—climate catastrophe, pandemics, fake news, political polarization—don't end in the short term.

The attitude needed in times like these is ‘scientific optimism.’

'Scientific optimism' is an attitude that temporarily accepts the possibility that 'a solution may be found someday' and continues to explore even when a solution is not yet in sight.

This is why the challenge of 'Fermat's Last Theorem', a difficult problem from 1637, continued until it was proven by Andrew Wiles 358 years later.

The reason mathematicians have continued to pursue challenges that have lasted for centuries is because they share the premise that “it is solvable.”

Without exaggerating our confidence, using failure as a clue to refine our approach, and harboring the collaborative imagination that we can solve problems not "alone" but "with our current and future colleagues"? This is how scientific optimism works.

Now let's extend this 'scientific optimism' to society.

Then, we can overcome the zero-sum problem where one person's gain becomes another person's loss.

In fact, while the world's population has grown significantly over the past century, the rate of extreme poverty has fallen from nearly 60% to less than 10%.

This is not the result of dividing resources by taking them, but rather the result of increasing total production through innovation in science, technology, and systems.

The same goes for energy transition.

As the performance of low-carbon technologies like wind, solar, geothermal, and hydropower improve and their costs fall, the wasteful disputes over who uses what will diminish, converging towards safer and cheaper options.

When the can-do spirit of science meets trust and collaborative design, hope becomes a result, not a slogan.

Based on the trust of wise individuals, not the extreme crowd

Third Millennium Human Solidarity

Even if an individual is equipped with scientific thinking and approaches problems with an optimistic attitude without giving up, something is still needed.

It's solidarity.

Why is solidarity necessary? Because the various challenges we face today cannot be solved by the efforts of one individual, but only through collective action.

Any solution will work if everyone shares the same facts, agrees on rules for avoiding more errors (false positives/false negatives), and has procedures for fairly sharing costs and benefits.

Moreover, in the world of the third millennium, where everyone is connected to the same ocean of data, if we don't design together who to trust and what procedures to use for making judgments, misinformation (the spread of incorrect information as fact) and echo chambers (an information environment where only the same opinions are repeated and confirmed) will destroy cooperation.

So solidarity lasts only on the basis of designed trust, not on feelings.

As a way to design trust, political scientist Robert Axelrod, famous for his research on the 'prisoner's dilemma' game, suggests the 'Tit for Tat' strategy (Chapter 18).

(1) Cooperate initially, (2) Respond accurately to betrayals in the next round, (3) Forgive immediately if the opponent returns to cooperation, and (4) Avoid unnecessary preemptive strikes. When these four rules become the norm for a community, the authors say, it can build resilient trust while discouraging free-riding.

Social optimism, the power to transform the goodwill of many people seeking cooperation into actual results, is the starting point of a new millennium of citizenship and a "second enlightenment."

The authors say:

We already have the tools and the rational optimism to move forward together.

Solidarity based on trust can be not just a slogan, but a new way of running society.

The new era of the third millennium can be rebooted based on these sophisticated trust designs.

In the future, humanity will face countless enormous challenges.

But if we join forces again based on this trust, we can overcome the current crisis by accepting it as an opportunity.

We just didn't write it

For thousands of years, science has been solving the world's mysteries, solving problems, and bringing a better life to humanity.

Scientists have long used these thinking tools to guide their daily lives, but they have not been widely used outside the scientific community.

But wherever we make decisions under uncertain circumstances and solve problems that affect our lives, scientific thinking has broad application and can help us in a vast array of areas and situations.

For example, there is a parental concern such as, “Should I leave my teenage child’s friendships alone so that he or she can develop trust in me and develop autonomy, or should I discipline him or her to prevent him or her from going down the wrong path?”

In times like these, it is more important to observe the child's behavior and determine the threshold at which parents should take action, rather than providing the 'correct answer'.

For example, you can set 'signals' such as 'when you become more late' or 'when your allowance usage suddenly changes', and start conversations or adjust the intensity of your intervention based on those signals.

The important thing is not to jump to conclusions based on a single action, but to observe the signals, make judgments, and adjust the standards little by little through conversation.

In science, this is called "threshold design based on a balance of sensitivity (the power not to miss what is there) and specificity (the power not to falsely filter out what is not there)" (Chapter 8).

In addition, we can change the way we approach problems through practical tools such as 'probabilistic thinking' (Chapter 4) to reduce the risk of decisions, 'distinguishing between signal and noise' (Chapter 6) to increase accuracy by separating meaning from noise in data, and 'Fermi estimation' (Chapter 11) to quickly obtain approximations by breaking down complex reality.

The goal of this book is to connect this scientific approach to the problems of life and work, equipping you with a "real-world problem-solving mindset."

scientific optimism

The 'can-do' spirit that says if you don't give up, you'll eventually solve the problem.

However, to solve problems of social reality beyond the individual level, simply approaching the problem scientifically is not enough.

We need to be optimistic that this problem can be solved someday.

Because most of the problems we face—climate catastrophe, pandemics, fake news, political polarization—don't end in the short term.

The attitude needed in times like these is ‘scientific optimism.’

'Scientific optimism' is an attitude that temporarily accepts the possibility that 'a solution may be found someday' and continues to explore even when a solution is not yet in sight.

This is why the challenge of 'Fermat's Last Theorem', a difficult problem from 1637, continued until it was proven by Andrew Wiles 358 years later.

The reason mathematicians have continued to pursue challenges that have lasted for centuries is because they share the premise that “it is solvable.”

Without exaggerating our confidence, using failure as a clue to refine our approach, and harboring the collaborative imagination that we can solve problems not "alone" but "with our current and future colleagues"? This is how scientific optimism works.

Now let's extend this 'scientific optimism' to society.

Then, we can overcome the zero-sum problem where one person's gain becomes another person's loss.

In fact, while the world's population has grown significantly over the past century, the rate of extreme poverty has fallen from nearly 60% to less than 10%.

This is not the result of dividing resources by taking them, but rather the result of increasing total production through innovation in science, technology, and systems.

The same goes for energy transition.

As the performance of low-carbon technologies like wind, solar, geothermal, and hydropower improve and their costs fall, the wasteful disputes over who uses what will diminish, converging towards safer and cheaper options.

When the can-do spirit of science meets trust and collaborative design, hope becomes a result, not a slogan.

Based on the trust of wise individuals, not the extreme crowd

Third Millennium Human Solidarity

Even if an individual is equipped with scientific thinking and approaches problems with an optimistic attitude without giving up, something is still needed.

It's solidarity.

Why is solidarity necessary? Because the various challenges we face today cannot be solved by the efforts of one individual, but only through collective action.

Any solution will work if everyone shares the same facts, agrees on rules for avoiding more errors (false positives/false negatives), and has procedures for fairly sharing costs and benefits.

Moreover, in the world of the third millennium, where everyone is connected to the same ocean of data, if we don't design together who to trust and what procedures to use for making judgments, misinformation (the spread of incorrect information as fact) and echo chambers (an information environment where only the same opinions are repeated and confirmed) will destroy cooperation.

So solidarity lasts only on the basis of designed trust, not on feelings.

As a way to design trust, political scientist Robert Axelrod, famous for his research on the 'prisoner's dilemma' game, suggests the 'Tit for Tat' strategy (Chapter 18).

(1) Cooperate initially, (2) Respond accurately to betrayals in the next round, (3) Forgive immediately if the opponent returns to cooperation, and (4) Avoid unnecessary preemptive strikes. When these four rules become the norm for a community, the authors say, it can build resilient trust while discouraging free-riding.

Social optimism, the power to transform the goodwill of many people seeking cooperation into actual results, is the starting point of a new millennium of citizenship and a "second enlightenment."

The authors say:

We already have the tools and the rational optimism to move forward together.

Solidarity based on trust can be not just a slogan, but a new way of running society.

The new era of the third millennium can be rebooted based on these sophisticated trust designs.

In the future, humanity will face countless enormous challenges.

But if we join forces again based on this trust, we can overcome the current crisis by accepting it as an opportunity.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: September 22, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 412 pages | 598g | 148*220*25mm

- ISBN13: 9791171715015

- ISBN10: 1171715013

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)