Breath of the Earth

|

Description

Book Introduction

The skin of the Earth, the treasure trove of life, the foundation of labor, and the final destination of life.

Ecological and sociological exploration of soil

A soil ecology expedition completed by digging and running around the ground.

A grand story that changed the fate of humanity lies in a handful of dirt!

A story about the soil around the world and the people who depend on it, told by an ecologist who feels and records the breath of the soil.

Examining the relationship between land and people in various cultures around the world, it addresses contemporary human agricultural culture, soil biology and chemistry, terrestrial landscape changes, climate change, and sustainability issues.

From the landscape of Jindo, Korea, where graves and fields coexist, to the wisdom of Himalayan slash-and-burn farmers, to the fierce activity of earthworms that have 'invaded' the polar regions, from the dramatic moment when soil was born on a Hawaiian volcanic island to soil erosion sites around the world, amazing stories from the soils of the Earth, diligently collected through footwork, unfold.

Ecological and sociological exploration of soil

A soil ecology expedition completed by digging and running around the ground.

A grand story that changed the fate of humanity lies in a handful of dirt!

A story about the soil around the world and the people who depend on it, told by an ecologist who feels and records the breath of the soil.

Examining the relationship between land and people in various cultures around the world, it addresses contemporary human agricultural culture, soil biology and chemistry, terrestrial landscape changes, climate change, and sustainability issues.

From the landscape of Jindo, Korea, where graves and fields coexist, to the wisdom of Himalayan slash-and-burn farmers, to the fierce activity of earthworms that have 'invaded' the polar regions, from the dramatic moment when soil was born on a Hawaiian volcanic island to soil erosion sites around the world, amazing stories from the soils of the Earth, diligently collected through footwork, unfold.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommendation

preface

1.

Shit - The first step toward a world where we don't destroy the Earth to survive.

Family Attitude | Human Excrement and Urine | Two Paths | Livestock Excrement and Urine | Real Excrement, Fake Excrement | Nitrogen and Carbon | Nitrogen Acrobatics | Nitrogen Poisoning | Livestock That Don't Graze | Soil Lost in Organic Matter | The Earth and Humans and People

2.

Hwajeon - The ancient wisdom of circulation and regeneration

Headhunting | The Name Slash-and-burn Farm | Nagaland | The Zoom Calendar | What Trees and Roots Do | Carbon, Nitrogen, and Phosphorus | A Defense Against Backwardness | The Precarious Balance Between Population and Slash-and-burn Farming | A Look to Zoom | Slash-and-burn Farming Is Also Innovating | The Healthy Slash-and-burn Farming

3.

The Plow - Towards Labor That Does Not Betray Life

The Punishment of Plowing | Universal Labor | The Farmer's Weapon | Innovation in Plow Technology | Social Innovation Driven by Plows and Livestock | The Free Ox, Mithun | The Rise of the Tractor | Until the Last Blade of Grass | Holy Grail | Labor That Saves

4.

The magic unfolds in the fields - fields without fields

Rice | The Magic of Non-Paddy Fields | The Synergistic Effect of Rice and Non-Paddy Fields | Rice Fields, Fields, and Korea | Rice Fields after the Green Revolution

5.

Water - The Key to Understanding the Evolution of Land

Ice | Snow | Water | Rain | The Journey of Carbon | Carbon Trapped in Rocks | Forests, the Front Line of Glaciers | The Magic of Earthworm Cocoons | Soil Temperature and Reindeer Footprints | Mammoth Steppe | The Transformation of Water

6.

River - Where We Will Be Reborn

Dumulmeori | Budot | Twin Cities | Watermill | Buried River | The Gray Traces of Evaporation and Capillary Flow | Salt Fields | Rivers and Irrigation Canals | Flowing Yet Untiring

7.

Earthworm - Who ate all those fallen leaves?

Worm Hunting | The Front Line Against Invasive Worm Infestations | Fishing and Gardening | Riding Worms | The Polar Worms | The First Settlers | The Pandemic and the Alaskan Worm | Invaders from Asia | They Wriggle When You Step on Them

8.

The body of earth - peeled, ground and broken

A Body of Earth | A Moving Hawaii | The Age of Earth | An Island Without Streams | The River's Rein | Creative Destruction | Weather and Age | Barely Existing

9.

The Breath of the Earth - Human Breath, the Breath of the Earth, and Climate Change

Breathing | The Breath of the Earth | The Subject of Breath | A Forest with a Radius of 6 Meters | Carbon Neutrality, the Essence of Life | The Breath of the Earth, the Breath of the Earth

10.

Land - The future connects with the past in the soil

Inside the Dirt Hole | Grandfather's Grave | A Hundred Years of Solitude | Land of the Dead | A Storyteller I Met in Jindo | Dividing the Land | Abandoned Land | A Jangmok, a Tree for Burial of Children | Attitudes toward Soil | I Sang as a Jindo Person

Conclusion

main

Source of the illustration

Search

preface

1.

Shit - The first step toward a world where we don't destroy the Earth to survive.

Family Attitude | Human Excrement and Urine | Two Paths | Livestock Excrement and Urine | Real Excrement, Fake Excrement | Nitrogen and Carbon | Nitrogen Acrobatics | Nitrogen Poisoning | Livestock That Don't Graze | Soil Lost in Organic Matter | The Earth and Humans and People

2.

Hwajeon - The ancient wisdom of circulation and regeneration

Headhunting | The Name Slash-and-burn Farm | Nagaland | The Zoom Calendar | What Trees and Roots Do | Carbon, Nitrogen, and Phosphorus | A Defense Against Backwardness | The Precarious Balance Between Population and Slash-and-burn Farming | A Look to Zoom | Slash-and-burn Farming Is Also Innovating | The Healthy Slash-and-burn Farming

3.

The Plow - Towards Labor That Does Not Betray Life

The Punishment of Plowing | Universal Labor | The Farmer's Weapon | Innovation in Plow Technology | Social Innovation Driven by Plows and Livestock | The Free Ox, Mithun | The Rise of the Tractor | Until the Last Blade of Grass | Holy Grail | Labor That Saves

4.

The magic unfolds in the fields - fields without fields

Rice | The Magic of Non-Paddy Fields | The Synergistic Effect of Rice and Non-Paddy Fields | Rice Fields, Fields, and Korea | Rice Fields after the Green Revolution

5.

Water - The Key to Understanding the Evolution of Land

Ice | Snow | Water | Rain | The Journey of Carbon | Carbon Trapped in Rocks | Forests, the Front Line of Glaciers | The Magic of Earthworm Cocoons | Soil Temperature and Reindeer Footprints | Mammoth Steppe | The Transformation of Water

6.

River - Where We Will Be Reborn

Dumulmeori | Budot | Twin Cities | Watermill | Buried River | The Gray Traces of Evaporation and Capillary Flow | Salt Fields | Rivers and Irrigation Canals | Flowing Yet Untiring

7.

Earthworm - Who ate all those fallen leaves?

Worm Hunting | The Front Line Against Invasive Worm Infestations | Fishing and Gardening | Riding Worms | The Polar Worms | The First Settlers | The Pandemic and the Alaskan Worm | Invaders from Asia | They Wriggle When You Step on Them

8.

The body of earth - peeled, ground and broken

A Body of Earth | A Moving Hawaii | The Age of Earth | An Island Without Streams | The River's Rein | Creative Destruction | Weather and Age | Barely Existing

9.

The Breath of the Earth - Human Breath, the Breath of the Earth, and Climate Change

Breathing | The Breath of the Earth | The Subject of Breath | A Forest with a Radius of 6 Meters | Carbon Neutrality, the Essence of Life | The Breath of the Earth, the Breath of the Earth

10.

Land - The future connects with the past in the soil

Inside the Dirt Hole | Grandfather's Grave | A Hundred Years of Solitude | Land of the Dead | A Storyteller I Met in Jindo | Dividing the Land | Abandoned Land | A Jangmok, a Tree for Burial of Children | Attitudes toward Soil | I Sang as a Jindo Person

Conclusion

main

Source of the illustration

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

In 16th-century China, associations or guilds were organized to collect urban dung.

(...) In Edo and Osaka during the Tokugawa period, if the landlord owned the excrement from the building, the tenant had the right to sell urine.

The building owner set the rent based on the income he would make from selling the tenants' excrement, and sold the collected excrement to excrement collectors who came by at the right time.

A dung collector was a trader who bought dung in the city and sold it in the countryside.

As a resource, feces fit well with the capitalist circulation of money.

The excrement of people moving from city to country was not only a food solution in Asia, but also a way to maintain public sanitation in rapidly growing cities.

--- p.37~38

Nitrogen is a precious element in terrestrial ecosystems.

Ninety percent of temperate ecosystems and nearly half of tropical ecosystems are nitrogen-limited.

This means that plant production increases simply by adding nitrogen to the soil.

A characteristic of a nitrogen-limited ecosystem is that even if other nutrients such as phosphorus or potassium are added, there is no significant increase in production, but when nitrogen is added without any other nutrients, there is an abrupt response.

--- p.46

Composting is simply the process of adjusting the ratio of carbon to nitrogen.

The desirable carbon to nitrogen ratio for composting raw materials is often considered to be around 30 to 1.

If the carbon content is lower than 30 units, it will be in a nitrogen-excess state and will produce foul-smelling ammonia, and if it is higher than 30, it will rot very slowly like the straw mentioned above.

The carbon to nitrogen ratio of the finished compost, which makes it an optimal fertilizer when applied to the soil, is 10 to 15 to 1.

This is where shit's strongest point lies.

--- p.49

Nitrogen makes up 78 percent of atmospheric molecules.

In terms of quantity, there are 4,000 trillion (3.9×10^15) tons of nitrogen floating in the Earth's atmosphere, so our bodies, which walk with only the soles of our feet on the ground, are like wading through a sea of nitrogen.

--- p.51

It is not possible for lettuce and peppers to grow thick and green in a wasteland of yellow soil devoid of any organic matter.

Korea is one of the countries that provides the largest amount of nitrogen fertilizer.

In 2021, 137 kilograms of nitrogen fertilizer per hectare were applied.

--- p.59

Even in the mountainous regions of Nagaland, where weathering and erosion occur relentlessly, soil remains because roots create the soil.

Just as there are roots because there is soil, there are also soil because there are roots.

Without the tenacity of their roots, tropical trees would not be able to reach their full growth potential despite the warm, water-rich environment.

--- p.83

In 2014, I met Professor Kim Pil-ju of Pyongyang University of Science and Technology in Seoul.

I asked him, an agronomist who has dedicated his life to solving North Korea's food problem, what machine would be needed to increase North Korea's agricultural production?

“It’s a rock crusher.” It was an unexpected answer.

“North Korea’s soil acidification is so severe that lime must be spread, so a limestone crusher is needed.” --- p.87

Earth is the beginning and the end of humanity.

As University of Wisconsin soil scientist Francis Hall (1913–2002) said, “For a moment we are not soil.”

Genesis says that even for a 'moment' the earth is the foundation of labor.

Destroying the soil is killing one's homeland and destroying a place to return to, yet it is the fate of humans to have to till the soil in order to make a living.

The plow is at the center of the irony that the labor we do to earn a living betrays humanity.

--- p.107

The Green Revolution saved countless people from starvation, but it also created problems of population growth and environmental destruction.

In this vein, conservation agriculture is a paradigm shift in farming practices that protects soil cover and promotes biodiversity.

However, the plow problem was only replaced by a herbicide problem.

Organic farming, an alternative, rejects the chemical fertilizers and pesticides created by modern agricultural technology and continues the long tradition of increasing agricultural productivity through an understanding of the ecological system, but it still faces the problem of the plow.

Innovation is still desperately needed in the place of the plow.

--- p.133

Rice has a unique physiology that allows it to transform into a wetland plant depending on the situation.

In other words, depending on whether it is submerged in water or not, ventilation tissue may or may not be formed.

The only major crop that can grow and root in waterlogged soil is rice.

When competing plants—commonly called weeds—choke in the water-filled fields, rice plants put on snorkels.

Therefore, filling the field with water to submerge the soil is a strategy to irrigate the rice while also removing weeds.

--- p.147

Compared to field soil, paddy soil has a higher organic matter content even when the same amount of dead organisms are buried there.

While artificial wetlands built by farmers increase soil organic matter content by slowing the rate of organic matter decomposition, ploughing and tilling further increase the organic matter content by forcing the remains of weeds and other organisms living in the paddy water into the anaerobic soil.

--- p.156

In other words, filling the fields with water is also a device to prevent soil acidification, which is a consequence of crop cultivation.

So, what would be the rational choice for an East Asian or Korean farmer, given the choice between rice paddies and dry fields? Whether it's disaster resistance or the sustainability it leaves for future generations, if possible, they'd likely choose rice paddies.

Despite high population densities and concentrations, rice farming in Asia has been able to persist for thousands of years without depleting soil fertility because rice was grown in flooded paddies rather than dry fields, and because the physiological characteristics of the rice plant and the integration of rice paddies into an organic system.

--- p.159

In 2008, when I was tired of being an assistant professor and was walking along the river, a groundbreaking paper was published about my walks.

Bob Walter and Dorothy Meritz made the radical claim that the banks blocking the rivers on both sides of the falls were not natural but the product of a mill dam.

It was said that the rivers of Piedmont are shaped the way they are today because of European settlers.

--- p.225~226

If earthworms arrived with the white man, what would the Ojibwe call them? Ojibwe speakers, who lived around the glaciated Great Lakes, likely never encountered earthworms, so perhaps they didn't even have a word for them. Does the Ojibwe language reflect the arrival of earthworms with the white man? I reached out to Professor John Nichols, an Ojibwe language researcher at the University of Minnesota's Department of American Indian Studies.

“Oh! I see.

The earthworm was an invasive species.

Now it all makes sense.

“I’ve always wondered why there’s no word for earthworm in Ojibwe,” he said. “For example, an Ojibwe speaker I interviewed at the Canadian border used the long phrase “long, coiled worm” (Ojibwe transliterated into English as moose gaa-ginwaabiigizid) to refer to earthworms.

--- p.279~280

On the other side of those who sing the praises of earthworms, I have been studying earthworms.

When it is said that earthworms make holes in the field to loosen the soil and allow water and air to flow, I have seen the opposite phenomenon.

With the invasion of earthworms, the soils of forests in Minnesota, Alaska, and Sweden have changed from fluffy, water- and air-permeable structures to hard, compact structures of mineral matter.

When it comes to earthworms, they help plants grow by circulating organic matter and nutrients, and I have personally witnessed and documented how, in a forest in an old glacial zone, hundreds of years of accumulated nutrients were lost in a matter of years due to an invasion of earthworms.

When I say that earthworms create fertile soil, I see native plants and animals losing their habitats to invasive earthworms.

When I hear the argument that we should actively utilize earthworms to revitalize the soil and reduce waste, I hope that the earthworms will just do their job well where they are now.

--- p.283

5 million years old! You won't find dirt older than this in Hawaii.

If you try hard, you might find it? That's not what I mean.

The islands beyond Kauai cannot exist above ground, having succumbed to subsidence and erosion over more than five million years and soon submerged.

If we imagine the earth as an actor that shows the dynamics of life and death, then the island is the stage.

Just as actors appear and disappear, so too does the stage.

--- p.302

The sight of new soil and new land being created on the Big Island is dramatic.

A hole in the earth's crust must be torn, red lava must flow, burning volcanic ash must fly, forests must catch fire, animals and people must flee, and the sky must turn ashen before a new land surface can be created.

It seems that the soil that has endured the arduous process of birth cannot have a weak body.

But the earthy body, contrary to our expectations that it would be unchanging and stable, barely exists.

On a volcanic island, soil is the product of lava formed from magma falling into the thermodynamic hell of the landmass.

Organic matter in the soil is also in an unstable state, temporarily bound to solar energy by atmospheric carbon dioxide and underground water.

The earthen body is still constantly decomposing towards a state of thermodynamic equilibrium under various winds.

--- p.317

Soil respiration is a great breath.

The amount of carbon dioxide emitted from burning fossil fuels, the main culprit of climate change, is 36.8 billion tons as of 2023.

The amount of carbon dioxide that the soil releases each year is roughly ten times that amount.

Yet, until humans began burning fossil fuels, atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations did not exceed 300 ppm for the past 800,000 years.

Because on a global scale, soil has not yet reached the edge of carbon neutrality.

Saying that soil is carbon neutral means that the amount of carbon dioxide that the soil exhales has been converted into carbon dioxide from the organic matter produced through photosynthesis, which has entered the soil through the dead bodies of plants and animals.

The reason why the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has been stable throughout Earth's long history is because terrestrial ecosystems, including soil and plants, have never strayed from the edge of carbon neutrality, and the oceans that surround 70 percent of the Earth have never strayed from the edge of carbon neutrality.

--- p.338~340

Atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations vary with seasons.

The three reasons for this are the concentration of land in the Northern Hemisphere, plant photosynthesis, and soil respiration.

(...) The difference in carbon dioxide concentration between summer and winter is 5 to 7 ppm at the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii.

It is truly a shame that the breath of this beautiful and wonderful Earth is overshadowed by the disastrous news of the annual average carbon dioxide concentration increasing year after year.

--- p.344

The Ajangmok tree seen from Sangmanri Village revealed its existence on its own without any effort to find it.

This elegant pine tree was at least a foot taller than the surrounding, evenly growing trees.

Within a 20-30 meter radius around the ajang tree, the surrounding smaller trees, which were all the same height, seemed to be oppressed by the ajang tree's might.

(...) In Edo and Osaka during the Tokugawa period, if the landlord owned the excrement from the building, the tenant had the right to sell urine.

The building owner set the rent based on the income he would make from selling the tenants' excrement, and sold the collected excrement to excrement collectors who came by at the right time.

A dung collector was a trader who bought dung in the city and sold it in the countryside.

As a resource, feces fit well with the capitalist circulation of money.

The excrement of people moving from city to country was not only a food solution in Asia, but also a way to maintain public sanitation in rapidly growing cities.

--- p.37~38

Nitrogen is a precious element in terrestrial ecosystems.

Ninety percent of temperate ecosystems and nearly half of tropical ecosystems are nitrogen-limited.

This means that plant production increases simply by adding nitrogen to the soil.

A characteristic of a nitrogen-limited ecosystem is that even if other nutrients such as phosphorus or potassium are added, there is no significant increase in production, but when nitrogen is added without any other nutrients, there is an abrupt response.

--- p.46

Composting is simply the process of adjusting the ratio of carbon to nitrogen.

The desirable carbon to nitrogen ratio for composting raw materials is often considered to be around 30 to 1.

If the carbon content is lower than 30 units, it will be in a nitrogen-excess state and will produce foul-smelling ammonia, and if it is higher than 30, it will rot very slowly like the straw mentioned above.

The carbon to nitrogen ratio of the finished compost, which makes it an optimal fertilizer when applied to the soil, is 10 to 15 to 1.

This is where shit's strongest point lies.

--- p.49

Nitrogen makes up 78 percent of atmospheric molecules.

In terms of quantity, there are 4,000 trillion (3.9×10^15) tons of nitrogen floating in the Earth's atmosphere, so our bodies, which walk with only the soles of our feet on the ground, are like wading through a sea of nitrogen.

--- p.51

It is not possible for lettuce and peppers to grow thick and green in a wasteland of yellow soil devoid of any organic matter.

Korea is one of the countries that provides the largest amount of nitrogen fertilizer.

In 2021, 137 kilograms of nitrogen fertilizer per hectare were applied.

--- p.59

Even in the mountainous regions of Nagaland, where weathering and erosion occur relentlessly, soil remains because roots create the soil.

Just as there are roots because there is soil, there are also soil because there are roots.

Without the tenacity of their roots, tropical trees would not be able to reach their full growth potential despite the warm, water-rich environment.

--- p.83

In 2014, I met Professor Kim Pil-ju of Pyongyang University of Science and Technology in Seoul.

I asked him, an agronomist who has dedicated his life to solving North Korea's food problem, what machine would be needed to increase North Korea's agricultural production?

“It’s a rock crusher.” It was an unexpected answer.

“North Korea’s soil acidification is so severe that lime must be spread, so a limestone crusher is needed.” --- p.87

Earth is the beginning and the end of humanity.

As University of Wisconsin soil scientist Francis Hall (1913–2002) said, “For a moment we are not soil.”

Genesis says that even for a 'moment' the earth is the foundation of labor.

Destroying the soil is killing one's homeland and destroying a place to return to, yet it is the fate of humans to have to till the soil in order to make a living.

The plow is at the center of the irony that the labor we do to earn a living betrays humanity.

--- p.107

The Green Revolution saved countless people from starvation, but it also created problems of population growth and environmental destruction.

In this vein, conservation agriculture is a paradigm shift in farming practices that protects soil cover and promotes biodiversity.

However, the plow problem was only replaced by a herbicide problem.

Organic farming, an alternative, rejects the chemical fertilizers and pesticides created by modern agricultural technology and continues the long tradition of increasing agricultural productivity through an understanding of the ecological system, but it still faces the problem of the plow.

Innovation is still desperately needed in the place of the plow.

--- p.133

Rice has a unique physiology that allows it to transform into a wetland plant depending on the situation.

In other words, depending on whether it is submerged in water or not, ventilation tissue may or may not be formed.

The only major crop that can grow and root in waterlogged soil is rice.

When competing plants—commonly called weeds—choke in the water-filled fields, rice plants put on snorkels.

Therefore, filling the field with water to submerge the soil is a strategy to irrigate the rice while also removing weeds.

--- p.147

Compared to field soil, paddy soil has a higher organic matter content even when the same amount of dead organisms are buried there.

While artificial wetlands built by farmers increase soil organic matter content by slowing the rate of organic matter decomposition, ploughing and tilling further increase the organic matter content by forcing the remains of weeds and other organisms living in the paddy water into the anaerobic soil.

--- p.156

In other words, filling the fields with water is also a device to prevent soil acidification, which is a consequence of crop cultivation.

So, what would be the rational choice for an East Asian or Korean farmer, given the choice between rice paddies and dry fields? Whether it's disaster resistance or the sustainability it leaves for future generations, if possible, they'd likely choose rice paddies.

Despite high population densities and concentrations, rice farming in Asia has been able to persist for thousands of years without depleting soil fertility because rice was grown in flooded paddies rather than dry fields, and because the physiological characteristics of the rice plant and the integration of rice paddies into an organic system.

--- p.159

In 2008, when I was tired of being an assistant professor and was walking along the river, a groundbreaking paper was published about my walks.

Bob Walter and Dorothy Meritz made the radical claim that the banks blocking the rivers on both sides of the falls were not natural but the product of a mill dam.

It was said that the rivers of Piedmont are shaped the way they are today because of European settlers.

--- p.225~226

If earthworms arrived with the white man, what would the Ojibwe call them? Ojibwe speakers, who lived around the glaciated Great Lakes, likely never encountered earthworms, so perhaps they didn't even have a word for them. Does the Ojibwe language reflect the arrival of earthworms with the white man? I reached out to Professor John Nichols, an Ojibwe language researcher at the University of Minnesota's Department of American Indian Studies.

“Oh! I see.

The earthworm was an invasive species.

Now it all makes sense.

“I’ve always wondered why there’s no word for earthworm in Ojibwe,” he said. “For example, an Ojibwe speaker I interviewed at the Canadian border used the long phrase “long, coiled worm” (Ojibwe transliterated into English as moose gaa-ginwaabiigizid) to refer to earthworms.

--- p.279~280

On the other side of those who sing the praises of earthworms, I have been studying earthworms.

When it is said that earthworms make holes in the field to loosen the soil and allow water and air to flow, I have seen the opposite phenomenon.

With the invasion of earthworms, the soils of forests in Minnesota, Alaska, and Sweden have changed from fluffy, water- and air-permeable structures to hard, compact structures of mineral matter.

When it comes to earthworms, they help plants grow by circulating organic matter and nutrients, and I have personally witnessed and documented how, in a forest in an old glacial zone, hundreds of years of accumulated nutrients were lost in a matter of years due to an invasion of earthworms.

When I say that earthworms create fertile soil, I see native plants and animals losing their habitats to invasive earthworms.

When I hear the argument that we should actively utilize earthworms to revitalize the soil and reduce waste, I hope that the earthworms will just do their job well where they are now.

--- p.283

5 million years old! You won't find dirt older than this in Hawaii.

If you try hard, you might find it? That's not what I mean.

The islands beyond Kauai cannot exist above ground, having succumbed to subsidence and erosion over more than five million years and soon submerged.

If we imagine the earth as an actor that shows the dynamics of life and death, then the island is the stage.

Just as actors appear and disappear, so too does the stage.

--- p.302

The sight of new soil and new land being created on the Big Island is dramatic.

A hole in the earth's crust must be torn, red lava must flow, burning volcanic ash must fly, forests must catch fire, animals and people must flee, and the sky must turn ashen before a new land surface can be created.

It seems that the soil that has endured the arduous process of birth cannot have a weak body.

But the earthy body, contrary to our expectations that it would be unchanging and stable, barely exists.

On a volcanic island, soil is the product of lava formed from magma falling into the thermodynamic hell of the landmass.

Organic matter in the soil is also in an unstable state, temporarily bound to solar energy by atmospheric carbon dioxide and underground water.

The earthen body is still constantly decomposing towards a state of thermodynamic equilibrium under various winds.

--- p.317

Soil respiration is a great breath.

The amount of carbon dioxide emitted from burning fossil fuels, the main culprit of climate change, is 36.8 billion tons as of 2023.

The amount of carbon dioxide that the soil releases each year is roughly ten times that amount.

Yet, until humans began burning fossil fuels, atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations did not exceed 300 ppm for the past 800,000 years.

Because on a global scale, soil has not yet reached the edge of carbon neutrality.

Saying that soil is carbon neutral means that the amount of carbon dioxide that the soil exhales has been converted into carbon dioxide from the organic matter produced through photosynthesis, which has entered the soil through the dead bodies of plants and animals.

The reason why the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has been stable throughout Earth's long history is because terrestrial ecosystems, including soil and plants, have never strayed from the edge of carbon neutrality, and the oceans that surround 70 percent of the Earth have never strayed from the edge of carbon neutrality.

--- p.338~340

Atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations vary with seasons.

The three reasons for this are the concentration of land in the Northern Hemisphere, plant photosynthesis, and soil respiration.

(...) The difference in carbon dioxide concentration between summer and winter is 5 to 7 ppm at the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii.

It is truly a shame that the breath of this beautiful and wonderful Earth is overshadowed by the disastrous news of the annual average carbon dioxide concentration increasing year after year.

--- p.344

The Ajangmok tree seen from Sangmanri Village revealed its existence on its own without any effort to find it.

This elegant pine tree was at least a foot taller than the surrounding, evenly growing trees.

Within a 20-30 meter radius around the ajang tree, the surrounding smaller trees, which were all the same height, seemed to be oppressed by the ajang tree's might.

--- p.375

Publisher's Review

The skin of the Earth, the treasure trove of life, the foundation of labor, and the final destination of life.

Ecological and sociological exploration of soil

A grand story that changed the fate of humanity lies in a handful of dirt!

★ 2024 University of Minnesota Outstanding Lectures

★ Recommended by ecologist Kim Dong-gil and anthropologist Jo Han-hye-jeong!

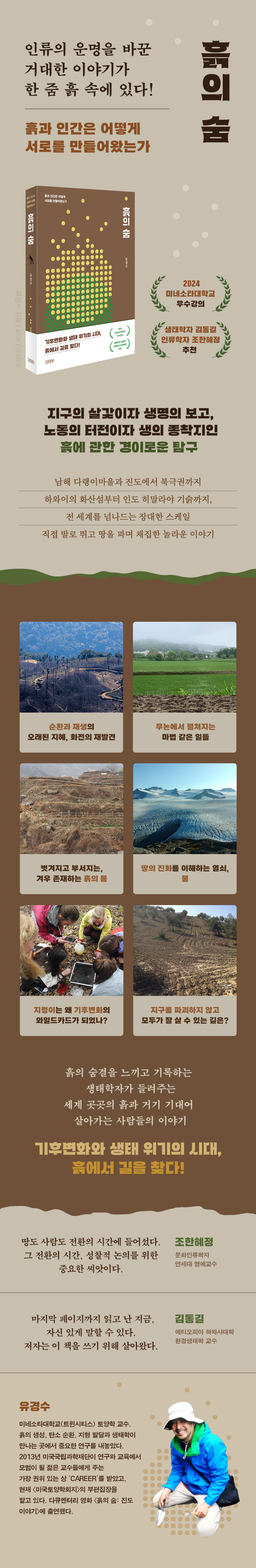

《The Breath of the Earth》 is a rare educational book in Korea that explores the earth, which is the natural world closest to us but has not received much attention.

Professor Kyung-Soo Yoo, a soil scientist who is actively researching at the University of Minnesota, examines the relationship between land and people in various cultures around the world, covering issues such as modern agriculture, soil biology and chemistry, changes in land landscapes, climate change, and sustainability.

It features major topics in soil science, including volcanic activity and soil formation through water and rivers, weathering and erosion, soil respiration, the carbon and nitrogen cycle, and the movement of nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus, all described together with human culture.

From the irrigation methods of ancient Mesopotamia to the desolate reality of today's olive groves, from the slash-and-burn fields of Nagaland in the Indian Himalayas to the landscapes of volcanic islands where the landscape is still rapidly changing, and even the ferocious activity of invasive earthworms that have advanced to the polar regions on the backs of humans, the author's diligent work uncovers astonishing stories from the earth's soil.

From Jindo, Jeollanam-do to the Arctic Circle

From the volcanic islands of Hawaii to the foothills of the Indian Himalayas

A grand exploration of soil ecology completed by digging and running around the ground!

The first thing that stands out is the extensive field research that spans the globe.

Even now, the author goes on field trips and exploration trips several times a year, and some of the places he visit include remote areas without internet access.

Dig the ground with a shovel until you're tired, check the layers, set up a chamber to regularly measure the amount of carbon dioxide coming out of the soil, and collect earthworms by pouring mustard water on the ground.

It is common to pitch a tent and spend days outdoors fighting flies and mosquitoes.

The author took ‘field first’ as his first principle, and “the things he saw while walking around for a long time and talking to local people as his first source of information” (p. 24). Thanks to this direct experience and the stories he heard, we can vividly experience how the land use situation in Jindo, which he visits almost every year, is changing, what earthworms are doing in Sweden and Alaska, and how serious the soil erosion is in the olive groves of Andalusia, Spain.

As Professor Kim Dong-gil, who wrote the recommendation, said, “Watching this arduous exploration, the thought of hardship naturally follows when leaving home, but thanks to the author’s efforts, we can touch the soil from all over the world with our own eyes, understand the ecology within it, and indirectly experience the various lives that depend on it.”

An ecologist who feels and records the breath of the soil tells us

Stories of the soil around the world and the people who depend on it for survival

Unlike typical science books, it is also noteworthy that it is rich in stories about people's lives and history.

These are stories that could not be included in a thesis, but that had been building up in my heart like layers of rock until they finally burst out.

Above all, the author's attitude of trying to understand the local culture without prejudice is noteworthy. For example, in the section on slash-and-burn farming in Nagaland, India (Chapter 2), he explains step by step that this is not evidence of backwardness, but rather an inevitable choice in a tropical environment lacking phosphorus.

It is not right to compare the large-scale slash-and-burn farming practices in places like the Amazon and Congo with the small-scale, traditional, sustainable farming practices.

The author marvels at the technological achievements of indigenous farmers who have maintained a close relationship with nature for centuries on the periphery of a globalized world, and shows that there are many possibilities for how humans and nature can relate.

Although it contains a considerable amount of academic content, the warm perspective and realistic narrative make it feel like reading an interesting travelogue.

The book is filled with accounts of the author's encounters with fellow researchers, family, and local people he met at the research site.

From Professor Paul Potter, an agroecologist who cycled across Africa and South America, to a family in a Sami village in Sweden who collected earthworms together, to the farmers in Jindo who are now almost like relatives, the countless connections recorded in the book seem to show a vast community connected by the glue of the soil.

The author's bold inclusion of conversations with seemingly unknown people, and even sometimes even self-confessional writings, stems from his belief that only through this method can we show that the soil is 'our' own problem (p. 15).

Shit and slash-and-burn, plows, and even the magic of the rice paddy

Finding a way to feed everyone without destroying the planet

The first half of the book presents an exploration of the roots of agriculture and civilization.

Chapters 1 ('Dung') and 2 ('Slash-and-burn Farming') cover the wisdom of maintaining soil fertility and circulation, Chapter 3 ('The Plow') covers the technological innovations of illiterate tenant farmers that completely transformed the medieval European world, and Chapter 4 ('Rice Fields') covers the essence of East Asian agriculture created by the combination of water and soil.

There are many parts that make you wonder how interesting the story of farming can be, including the competition between merchants to collect good manure before the advent of chemical fertilizers, the fact that the square Celtic fields and narrow, medieval manor farms are shaped that way because of the type of plow and the way it was plowed, and what happens in the soil when the field is irrigated and harrowed.

Readers interested in the future of agriculture, which bears the burden of feeding the planet's 8 billion people, will understand the urgency of moving away from the overuse of nitrogen fertilizers, the challenges of pesticide-free or no-till farming, and the weighty question of how a world without destroying the planet to feed humans is possible.

Who ate all those fallen leaves?

The Two Faces of the Earthworm, an Eco-Friendly Icon

The author is famous for his research on 'global worming' and its impact on global warming, which is introduced in Chapter 7.

Twenty or thirty years ago, Minnesota residents discovered a site where the thick layer of fallen leaves that had covered the forest for centuries had disappeared, exposing a hard, mineral-rich soil floor.

Researchers at the University of Minnesota discovered that the culprits who ate the fallen leaves were earthworms.

Northern North America was devoid of earthworms for thousands of years after the last Ice Age. But in recent decades, earthworms have been introduced along with fishing bait and gardening soil.

The problem is that earthworms quickly break down fallen leaves and organic matter.

As a result, the ecological structure of the forest, which had the fallen leaves as an important element, collapses, and carbon stored underground is released into the atmosphere, accelerating climate change.

Witnessing the leaf litter disappearing at a rate of 5 to 10 meters per year, matching the speed at which earthworms spread, the author realizes just how much change a tiny creature underfoot can bring about.

Since then, earthworms have become one of the author's main research subjects, and the process of the author personally discovering when and how earthworms were introduced to the Swedish polar regions is as exciting as a detective story.

Earthworms, once considered symbols of fertility and eco-friendliness, are now attracting attention as invasive species and destroyers in some lands, and are now seen as a 'wild card' of climate change.

The surprisingly fragile body of earth, the rough and rapid breath of earth

In an age of climate change and ecological crisis, for the sake of caring for our common home.

The latter part of the book expands on the idea of soil.

Valleys carved by glaciers with relentless force, coastal features raised by melting glaciers, the mammoth steppe, grasslands formed by the melting snow of large herbivores like mammoths, Mesopotamian irrigation canals rising above the floodplains of the plains, dramatic scenes in the heart of volcanic islands where new soil is being created...

It takes readers into a vast world that spans tens of thousands of years in time and encompasses polar regions, deserts, and tropical regions in space.

What this journey reveals is that the earth's soil, as majestic as it is, is fragile, constantly crumbling under the influence of natural weathering and easily eroded and transformed by human land use.

Chapter 5 ('Water') shows the transformation of water into solid, liquid, and gas, and the resulting changes in the soil, while Chapter 6 ('River') shows how rivers, land, and human activities have shaped and co-evolved with each other.

As we follow the earth moving along the waterway and the process of life being built and destroyed on top of it, we come to realize that earth, water, and life form one giant cycle.

Chapter 8 ('The Body of Soil') explores the history of soil from birth to death, and Chapter 9 ('The Breath of Soil') explores the respiration and carbon cycle of living things in the soil.

Soil emits 10 times more carbon dioxide each year than humanity's fossil fuel emissions, yet it has remained carbon neutral for many years.

However, this balance is being disrupted as indiscriminate land use and rising atmospheric temperatures accelerate the decomposition of organic matter in the soil.

“The coarsening and eroding soil is a signal from the broken, hidden body of the soil, and is an important part of the climate change caused by the industrial civilization that burns fossil fuels.” (p. 21)

Man comes from the dust and returns to the dust.

As soil scientist Francis Hall said, we are temporarily not soil (p. 107), and during that time we have no choice but to live by working on the soil and relying on it.

The message of this book is that the answer to overcoming climate change and the ecological crisis lies within the soil that sustains our ecosystem, the source of our food production, and the vast, breathing soil.

And the clue to that answer will appear before the eyes of those who regard and nurture Earth, the only habitat for humans, as our 'common home.'

Ecological and sociological exploration of soil

A grand story that changed the fate of humanity lies in a handful of dirt!

★ 2024 University of Minnesota Outstanding Lectures

★ Recommended by ecologist Kim Dong-gil and anthropologist Jo Han-hye-jeong!

《The Breath of the Earth》 is a rare educational book in Korea that explores the earth, which is the natural world closest to us but has not received much attention.

Professor Kyung-Soo Yoo, a soil scientist who is actively researching at the University of Minnesota, examines the relationship between land and people in various cultures around the world, covering issues such as modern agriculture, soil biology and chemistry, changes in land landscapes, climate change, and sustainability.

It features major topics in soil science, including volcanic activity and soil formation through water and rivers, weathering and erosion, soil respiration, the carbon and nitrogen cycle, and the movement of nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus, all described together with human culture.

From the irrigation methods of ancient Mesopotamia to the desolate reality of today's olive groves, from the slash-and-burn fields of Nagaland in the Indian Himalayas to the landscapes of volcanic islands where the landscape is still rapidly changing, and even the ferocious activity of invasive earthworms that have advanced to the polar regions on the backs of humans, the author's diligent work uncovers astonishing stories from the earth's soil.

From Jindo, Jeollanam-do to the Arctic Circle

From the volcanic islands of Hawaii to the foothills of the Indian Himalayas

A grand exploration of soil ecology completed by digging and running around the ground!

The first thing that stands out is the extensive field research that spans the globe.

Even now, the author goes on field trips and exploration trips several times a year, and some of the places he visit include remote areas without internet access.

Dig the ground with a shovel until you're tired, check the layers, set up a chamber to regularly measure the amount of carbon dioxide coming out of the soil, and collect earthworms by pouring mustard water on the ground.

It is common to pitch a tent and spend days outdoors fighting flies and mosquitoes.

The author took ‘field first’ as his first principle, and “the things he saw while walking around for a long time and talking to local people as his first source of information” (p. 24). Thanks to this direct experience and the stories he heard, we can vividly experience how the land use situation in Jindo, which he visits almost every year, is changing, what earthworms are doing in Sweden and Alaska, and how serious the soil erosion is in the olive groves of Andalusia, Spain.

As Professor Kim Dong-gil, who wrote the recommendation, said, “Watching this arduous exploration, the thought of hardship naturally follows when leaving home, but thanks to the author’s efforts, we can touch the soil from all over the world with our own eyes, understand the ecology within it, and indirectly experience the various lives that depend on it.”

An ecologist who feels and records the breath of the soil tells us

Stories of the soil around the world and the people who depend on it for survival

Unlike typical science books, it is also noteworthy that it is rich in stories about people's lives and history.

These are stories that could not be included in a thesis, but that had been building up in my heart like layers of rock until they finally burst out.

Above all, the author's attitude of trying to understand the local culture without prejudice is noteworthy. For example, in the section on slash-and-burn farming in Nagaland, India (Chapter 2), he explains step by step that this is not evidence of backwardness, but rather an inevitable choice in a tropical environment lacking phosphorus.

It is not right to compare the large-scale slash-and-burn farming practices in places like the Amazon and Congo with the small-scale, traditional, sustainable farming practices.

The author marvels at the technological achievements of indigenous farmers who have maintained a close relationship with nature for centuries on the periphery of a globalized world, and shows that there are many possibilities for how humans and nature can relate.

Although it contains a considerable amount of academic content, the warm perspective and realistic narrative make it feel like reading an interesting travelogue.

The book is filled with accounts of the author's encounters with fellow researchers, family, and local people he met at the research site.

From Professor Paul Potter, an agroecologist who cycled across Africa and South America, to a family in a Sami village in Sweden who collected earthworms together, to the farmers in Jindo who are now almost like relatives, the countless connections recorded in the book seem to show a vast community connected by the glue of the soil.

The author's bold inclusion of conversations with seemingly unknown people, and even sometimes even self-confessional writings, stems from his belief that only through this method can we show that the soil is 'our' own problem (p. 15).

Shit and slash-and-burn, plows, and even the magic of the rice paddy

Finding a way to feed everyone without destroying the planet

The first half of the book presents an exploration of the roots of agriculture and civilization.

Chapters 1 ('Dung') and 2 ('Slash-and-burn Farming') cover the wisdom of maintaining soil fertility and circulation, Chapter 3 ('The Plow') covers the technological innovations of illiterate tenant farmers that completely transformed the medieval European world, and Chapter 4 ('Rice Fields') covers the essence of East Asian agriculture created by the combination of water and soil.

There are many parts that make you wonder how interesting the story of farming can be, including the competition between merchants to collect good manure before the advent of chemical fertilizers, the fact that the square Celtic fields and narrow, medieval manor farms are shaped that way because of the type of plow and the way it was plowed, and what happens in the soil when the field is irrigated and harrowed.

Readers interested in the future of agriculture, which bears the burden of feeding the planet's 8 billion people, will understand the urgency of moving away from the overuse of nitrogen fertilizers, the challenges of pesticide-free or no-till farming, and the weighty question of how a world without destroying the planet to feed humans is possible.

Who ate all those fallen leaves?

The Two Faces of the Earthworm, an Eco-Friendly Icon

The author is famous for his research on 'global worming' and its impact on global warming, which is introduced in Chapter 7.

Twenty or thirty years ago, Minnesota residents discovered a site where the thick layer of fallen leaves that had covered the forest for centuries had disappeared, exposing a hard, mineral-rich soil floor.

Researchers at the University of Minnesota discovered that the culprits who ate the fallen leaves were earthworms.

Northern North America was devoid of earthworms for thousands of years after the last Ice Age. But in recent decades, earthworms have been introduced along with fishing bait and gardening soil.

The problem is that earthworms quickly break down fallen leaves and organic matter.

As a result, the ecological structure of the forest, which had the fallen leaves as an important element, collapses, and carbon stored underground is released into the atmosphere, accelerating climate change.

Witnessing the leaf litter disappearing at a rate of 5 to 10 meters per year, matching the speed at which earthworms spread, the author realizes just how much change a tiny creature underfoot can bring about.

Since then, earthworms have become one of the author's main research subjects, and the process of the author personally discovering when and how earthworms were introduced to the Swedish polar regions is as exciting as a detective story.

Earthworms, once considered symbols of fertility and eco-friendliness, are now attracting attention as invasive species and destroyers in some lands, and are now seen as a 'wild card' of climate change.

The surprisingly fragile body of earth, the rough and rapid breath of earth

In an age of climate change and ecological crisis, for the sake of caring for our common home.

The latter part of the book expands on the idea of soil.

Valleys carved by glaciers with relentless force, coastal features raised by melting glaciers, the mammoth steppe, grasslands formed by the melting snow of large herbivores like mammoths, Mesopotamian irrigation canals rising above the floodplains of the plains, dramatic scenes in the heart of volcanic islands where new soil is being created...

It takes readers into a vast world that spans tens of thousands of years in time and encompasses polar regions, deserts, and tropical regions in space.

What this journey reveals is that the earth's soil, as majestic as it is, is fragile, constantly crumbling under the influence of natural weathering and easily eroded and transformed by human land use.

Chapter 5 ('Water') shows the transformation of water into solid, liquid, and gas, and the resulting changes in the soil, while Chapter 6 ('River') shows how rivers, land, and human activities have shaped and co-evolved with each other.

As we follow the earth moving along the waterway and the process of life being built and destroyed on top of it, we come to realize that earth, water, and life form one giant cycle.

Chapter 8 ('The Body of Soil') explores the history of soil from birth to death, and Chapter 9 ('The Breath of Soil') explores the respiration and carbon cycle of living things in the soil.

Soil emits 10 times more carbon dioxide each year than humanity's fossil fuel emissions, yet it has remained carbon neutral for many years.

However, this balance is being disrupted as indiscriminate land use and rising atmospheric temperatures accelerate the decomposition of organic matter in the soil.

“The coarsening and eroding soil is a signal from the broken, hidden body of the soil, and is an important part of the climate change caused by the industrial civilization that burns fossil fuels.” (p. 21)

Man comes from the dust and returns to the dust.

As soil scientist Francis Hall said, we are temporarily not soil (p. 107), and during that time we have no choice but to live by working on the soil and relying on it.

The message of this book is that the answer to overcoming climate change and the ecological crisis lies within the soil that sustains our ecosystem, the source of our food production, and the vast, breathing soil.

And the clue to that answer will appear before the eyes of those who regard and nurture Earth, the only habitat for humans, as our 'common home.'

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: August 12, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 420 pages | 145*210*30mm

- ISBN13: 9791173322815

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)