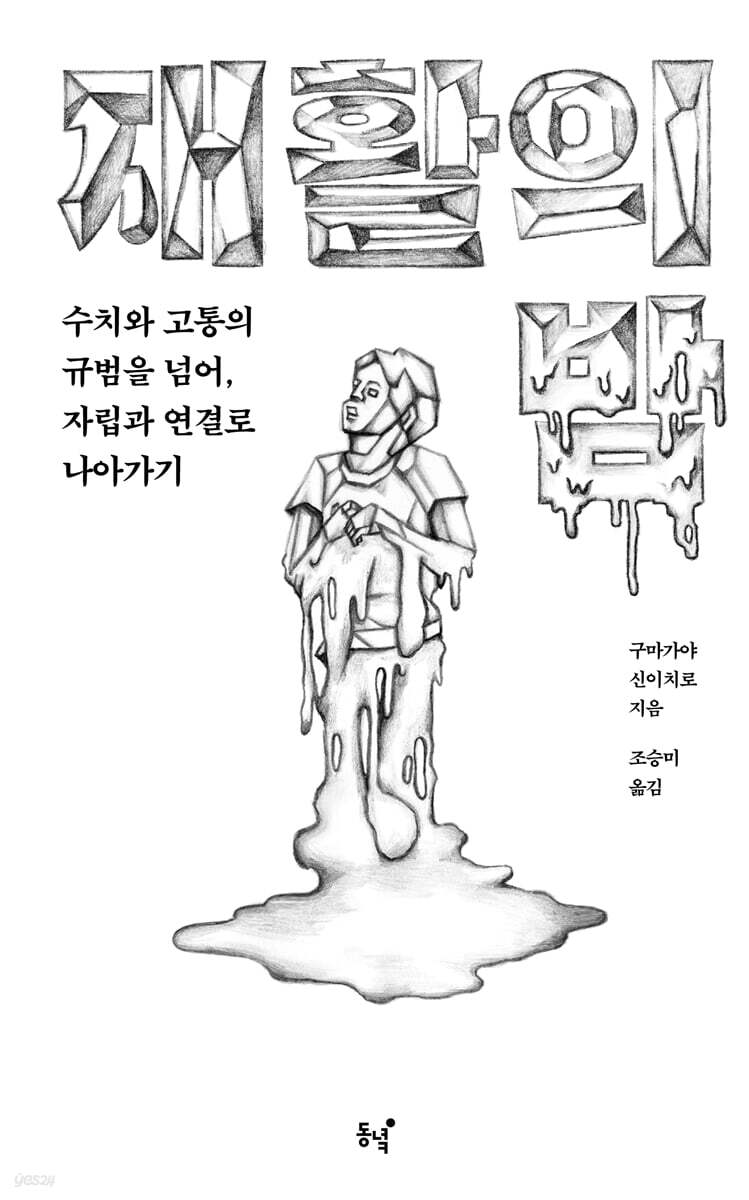

Rehabilitation Night

|

Description

Book Introduction

★★★ Recommended by Kim Do-hyun, Ha Eun-bin, and Moon Young-min ★★★

“A multidisciplinary and reflective self-report on rehabilitation by a person with a disability.”

“I hope you will open this book not to know or understand, but to touch and be touched.”

“A book that opens up new possibilities for thinking about the relationship between disability and the world.”

A person with cerebral palsy and a person in the field of research

Representative researcher Shinichiro Kumagaya

A fierce study of non-normative movements, relationships, sexuality, independence, and life.

After 'rehabilitation nights' where 'normal' body movements were forced,

I was struggling to figure out how to interact with the world with my damaged body.

A sensual and captivating autobiographical story

A record of Shinichiro Kumagaya, a pediatrician, life scientist, and person with congenital spastic cerebral palsy, reflecting on his experiences with rehabilitation treatment through adolescence and his subsequent independent living, exploring the body and disability, norms and sexuality, independence and life in an interdisciplinary and reflective manner.

A book that poses fundamental questions about disability and independence from a multidisciplinary perspective, including disability studies, sociology, medicine, and engineering.

This is the first autobiographical essay by Shinichiro Kumagaya, who wrote the famous sentence, “Independence is not the absence of dependence, but the state of being able to choose to depend.” It won the 9th Shincho Documentary Award and has had a significant influence on the Japanese party movement and research in which people with disabilities and illnesses take the lead.

“A multidisciplinary and reflective self-report on rehabilitation by a person with a disability.”

“I hope you will open this book not to know or understand, but to touch and be touched.”

“A book that opens up new possibilities for thinking about the relationship between disability and the world.”

A person with cerebral palsy and a person in the field of research

Representative researcher Shinichiro Kumagaya

A fierce study of non-normative movements, relationships, sexuality, independence, and life.

After 'rehabilitation nights' where 'normal' body movements were forced,

I was struggling to figure out how to interact with the world with my damaged body.

A sensual and captivating autobiographical story

A record of Shinichiro Kumagaya, a pediatrician, life scientist, and person with congenital spastic cerebral palsy, reflecting on his experiences with rehabilitation treatment through adolescence and his subsequent independent living, exploring the body and disability, norms and sexuality, independence and life in an interdisciplinary and reflective manner.

A book that poses fundamental questions about disability and independence from a multidisciplinary perspective, including disability studies, sociology, medicine, and engineering.

This is the first autobiographical essay by Shinichiro Kumagaya, who wrote the famous sentence, “Independence is not the absence of dependence, but the state of being able to choose to depend.” It won the 9th Shincho Documentary Award and has had a significant influence on the Japanese party movement and research in which people with disabilities and illnesses take the lead.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Preface to the Korean edition

Recommendation

Entering

Seojang Rehabilitation Camp

Chapter 1: Experience with Cerebral Palsy

1 Virtual reality in the brain

2. A body prone to tension

3 The pleasure of the folding knife phenomenon

4. Accepting movement and dealing with people

Chapter 2 Trainers and Trainees

1. Loose body

2 The body being stared at

3 Abandoned body

4. The body becomes stiff because the mind is involved.

5 When intervention in the body turns into violence

Dance with 6 college student trainers

Column: The Social History of Cerebral Palsy Rehabilitation

Chapter 3: Rehabilitation Night

1 Sunset

2. Room for a child who does not walk

3. The walking child's room

4 Women's Bathhouse

5 A boy obsessed with masturbation

Chapter 4: Indulgence

1. Fall into contrast

2 Unacceptable Sex

3 Norms, tension, sensuality

4 The girl who hit me

Column: Discipline Training and Masochism

Chapter 5: The Birth of Movement

1 Movement created with objects

(1) Connected to the toilet

(2) Idea of extracorporeal coordination structures

(3) How did electric wheelchairs change the world?

Movement created with two people

(1) Seeking a cooperative structure with objects - First year of residency

(2) Understanding the structure of cooperation with people - 2nd year of residency

3 Reasons Why 'Big Picture Goal Setting' Is Important

4 Focusing on and sharing the world

5 From helping each other to violence

Column - The Ground and the 'Relationship of Picking Up While Unpacking'

Chapter 6 Freedom in the Gap

1. Somewhere between amphibians and reptiles

2. A typist named 'Byeon-ui'

3 Be saved by the body

4. Tie, open, and connect

5 Towards Decline

Author's Note

Translator's Note

References

Recommendation

Entering

Seojang Rehabilitation Camp

Chapter 1: Experience with Cerebral Palsy

1 Virtual reality in the brain

2. A body prone to tension

3 The pleasure of the folding knife phenomenon

4. Accepting movement and dealing with people

Chapter 2 Trainers and Trainees

1. Loose body

2 The body being stared at

3 Abandoned body

4. The body becomes stiff because the mind is involved.

5 When intervention in the body turns into violence

Dance with 6 college student trainers

Column: The Social History of Cerebral Palsy Rehabilitation

Chapter 3: Rehabilitation Night

1 Sunset

2. Room for a child who does not walk

3. The walking child's room

4 Women's Bathhouse

5 A boy obsessed with masturbation

Chapter 4: Indulgence

1. Fall into contrast

2 Unacceptable Sex

3 Norms, tension, sensuality

4 The girl who hit me

Column: Discipline Training and Masochism

Chapter 5: The Birth of Movement

1 Movement created with objects

(1) Connected to the toilet

(2) Idea of extracorporeal coordination structures

(3) How did electric wheelchairs change the world?

Movement created with two people

(1) Seeking a cooperative structure with objects - First year of residency

(2) Understanding the structure of cooperation with people - 2nd year of residency

3 Reasons Why 'Big Picture Goal Setting' Is Important

4 Focusing on and sharing the world

5 From helping each other to violence

Column - The Ground and the 'Relationship of Picking Up While Unpacking'

Chapter 6 Freedom in the Gap

1. Somewhere between amphibians and reptiles

2. A typist named 'Byeon-ui'

3 Be saved by the body

4. Tie, open, and connect

5 Towards Decline

Author's Note

Translator's Note

References

Detailed image

Into the book

I went to rehab every day from when I was very young until I was eighteen.

Until the lower grades of elementary school, the routine was usually to divide the rehabilitation into three sessions per day for one hour each.

Once a month, I went to the welfare center and school for the disabled in the neighboring town to receive observation and guidance from experts.

And when summer vacation came, I headed across the sea to a facility in the mountains to participate in a rehabilitation camp.

--- p.18

When I arrive at the rehabilitation facility, my body is lifted from the wheelchair and placed on a cold floor covered with a short, woolen mat.

Without the wheelchair that came between me and the world, connecting and mediating various objects with me, my body is limited to relating to the limited scope of the floor and objects within a few centimeters of the floor.

The bookshelf or desk that was previously in contact with the wall is now much higher than your head.

It is similar to the ceiling in that you can only look at it because you can't reach it.

I feel like I'm back in the 'two-dimensional world' again.

In that state, the only thing that picks up my movements is the floor.

I'm going to be spending most of the next week with this floor.

It will move slowly in a crawling manner, like crawling on its stomach, feeling the temperature, friction, moisture, and smell of the floor.

The floor will accept this strange movement of mine and transform it into a form of 'movement'.

My movement is not a meaningless exercise that cuts through the air, but is given meaning by the floor.

This floor is the only thing that gives meaning to my movements.

--- p.20~21

I know well the world beyond the fall.

That is the world I used to be in.

I started using a wheelchair when I was around thirteen.

Until then, I had been moving around in two dimensions on the floor like an attached organism.

Fall back into the two-dimensional world.

Even now, having barely touched the three-dimensional world, there are still doors in my life that open wide like traps, leading to the two-dimensional world.

(…) But at the same time, the two-dimensional world is also a place I miss.

I have known this world for a long time.

I know how to live in this world.

Just leave me on the floor.

The floor is big and strong and holds me tightly.

It's okay to sleep soundly like a child, and it's okay to play and indulge in your favorite fantasies.

A sense of relief builds at returning to a familiar place from the past.

So falling to the floor is like a time slip for me, going back in time.

--- p.30~31

But why is my body so prone to falling? And why does just falling send me into a two-dimensional world? These questions might sound like strange, playful questions.

“Why? Since your body has a disability called cerebral palsy, wouldn’t it be natural for you to be incapacitated?” I think I might hear a retort like this, seemingly incredulous.

But I don't want such a superficial explanation.

Describing my experience using words like "cerebral palsy" or "disability" might make others feel like they know what I'm talking about, but it doesn't convey the essence of what I experienced.

I need words that can more vividly and clearly reproduce what I have experienced.

And in this book, I want to write an explanation that will allow the reader to vaguely relate to my experiences of falling and still falling.

So, I want to drag you, the readers, along and fall together.

--- p.31~32

When we feel the sensation of 'my body moving', it is not because we receive feedback information from the body that actually moved.

Regardless of whether or not the movement actually occurred, the result of the movement simulation performed by the 'internal model' in the posterior parietal lobe is mistaken for the actual movement (this illusion is called 'false proprioception').

In this way, there exists an 'image' in the brain that projects the body and the external world.

This is called the 'internal model'.

Whether or not we actually move, our consciousness experiences our own intentions, movements, and changes in the world within a virtual reality created by computations of our internal models.

--- p.42

In this way, from a young age, I internalized an image of 'normal movement' that I could not perform on my own.

There is naturally a gap between the image of 'normal movement' produced in this way and the actual movement of my body.

Because of the desire of those around me to fill this gap, I had to undergo rehabilitation for over a decade since I was young to be able to perform 'non-disabled movements'.

--- p.69

The trainer's movements are performed completely independently of my movements, and the trainer cannot pick up the signals of fear or pain emanating from my body.

The trainer is an uncompromising hitter, a powerful hitter who wields power over my body.

Soon, my body succumbs to the trainer's power, as if losing territory to the enemy.

My arms, legs, and waist all gave way to the trainer's strength one by one, and I lost all tension.

However, this process does not have the same pleasure as the folding knife phenomenon.

Rather, it feels like I'm taking my arms, legs, and waist off my body and handing them over to a trainer.

--- p.87

Unlike the 'relationship of letting go and giving in' where you let go and let go, in a situation like the 'relationship of looking/being looked at', you feel anxious and your body gradually becomes stiff.

However, this process does not last forever.

The vicious cycle of impatience and stiffness soon leads me to the sensation of defeat, much like in the crawling forward competition, as my movements become increasingly disorganized and directionless.

And the energy that has built up inside me from anxiety and stiffness, when it crosses a certain point, my whole body periodically trembles in convulsions and disappears into thin air, and the coordination structure within my body suddenly loosens and my body becomes limp.

--- p.91

Perhaps it was at this time that I first realized that the self-image of a "weak and small me" that lends itself to sensual contrasts is not something that is given to me for free, but something that I must constantly monitor and regulate to maintain.

I didn't really care when I was in elementary school, but when I entered middle school, I suddenly started to care about how other people saw me, so I started dieting.

--- p.158

When you feel like you're about to deviate from the norm, your body becomes stiff, and when you deviate from the norm, your body relaxes.

There is a sensuality to the repetitive movements of stiffness and relaxation surrounding these norms.

We were trapped in that ‘world of our own’ and endlessly indulged in it.

Where is the other who will bring me the sensuality that opens up into a 'relationship of letting go and picking up each other', the other who will accept my strange movements...?

--- p.182

The moment I saw the renovated bathroom, my body slowly moved as if it was opening up.

It felt like I was tuning my body to a new toilet.

The toilet that had driven me to defeat last time was now reaching out to pick up my movements.

As if drawn by the hand of the toilet, my body slightly relaxed its internal coordination structure, and the resulting play enabled the restructuring, or tuning, of the internal coordination structure.

My body has changed as a result of the bathroom renovation.

--- p.203

The way you perceive the world when you're in a power wheelchair is completely different than when you're not.

Just being able to move quickly to various places reduces the gap with the outside world, and our sense of distance in space changes, as if objects or places that were previously unrelated to us suddenly become close.

As the amount of change in movement, and even the way the world is seen, increases, the passage of time also seems to accelerate.

As my options for action expand dramatically, my body image can feel more empowered.

In this way, the electric wheelchair completely changed my image of the world, including my body.

--- p.222~223

My own unique movements, completed in this way, often include the assistant's body as an essential element.

And between me and my assistant, a strong physical and extra-physical coordination structure, or teamwork, is established.

For example, a colleague who is accustomed to assisting me when drawing blood knows my body's movement patterns very well, so even without me expressing it verbally, he or she can sense the 'meaning' of the subtle movements of my fingertips and adjust the position of his or her hand supporting the patient's elbow.

It was a magical experience, as if my assistant and I had expanded into one large body.

When my assistant and I, two bodies, work together to perform the exercise of drawing blood from the same object, the patient's arm, it feels like the boundary between my body and my assistant's body becomes blurred.

--- p.237~238

I think that in a tense situation, the opportunity to breathe is a kind of sensual motivation to put aside the big picture goals for a moment and get to know each other's bodies through communication.

Rather than a 'relationship of looking/being looked at' that is obsessed with achieving a goal, a mindset that prioritizes a 'relationship of letting go and giving to each other' where the body opens up and one feels a kind of joy in the process of communicating with each other even if one fails to achieve the goal and is defeated allows one to accept each other's body image and creates a cooperative structure.

Then the stiff team will start to move slowly and eventually reach the goal, even if it takes a long way around.

Until the lower grades of elementary school, the routine was usually to divide the rehabilitation into three sessions per day for one hour each.

Once a month, I went to the welfare center and school for the disabled in the neighboring town to receive observation and guidance from experts.

And when summer vacation came, I headed across the sea to a facility in the mountains to participate in a rehabilitation camp.

--- p.18

When I arrive at the rehabilitation facility, my body is lifted from the wheelchair and placed on a cold floor covered with a short, woolen mat.

Without the wheelchair that came between me and the world, connecting and mediating various objects with me, my body is limited to relating to the limited scope of the floor and objects within a few centimeters of the floor.

The bookshelf or desk that was previously in contact with the wall is now much higher than your head.

It is similar to the ceiling in that you can only look at it because you can't reach it.

I feel like I'm back in the 'two-dimensional world' again.

In that state, the only thing that picks up my movements is the floor.

I'm going to be spending most of the next week with this floor.

It will move slowly in a crawling manner, like crawling on its stomach, feeling the temperature, friction, moisture, and smell of the floor.

The floor will accept this strange movement of mine and transform it into a form of 'movement'.

My movement is not a meaningless exercise that cuts through the air, but is given meaning by the floor.

This floor is the only thing that gives meaning to my movements.

--- p.20~21

I know well the world beyond the fall.

That is the world I used to be in.

I started using a wheelchair when I was around thirteen.

Until then, I had been moving around in two dimensions on the floor like an attached organism.

Fall back into the two-dimensional world.

Even now, having barely touched the three-dimensional world, there are still doors in my life that open wide like traps, leading to the two-dimensional world.

(…) But at the same time, the two-dimensional world is also a place I miss.

I have known this world for a long time.

I know how to live in this world.

Just leave me on the floor.

The floor is big and strong and holds me tightly.

It's okay to sleep soundly like a child, and it's okay to play and indulge in your favorite fantasies.

A sense of relief builds at returning to a familiar place from the past.

So falling to the floor is like a time slip for me, going back in time.

--- p.30~31

But why is my body so prone to falling? And why does just falling send me into a two-dimensional world? These questions might sound like strange, playful questions.

“Why? Since your body has a disability called cerebral palsy, wouldn’t it be natural for you to be incapacitated?” I think I might hear a retort like this, seemingly incredulous.

But I don't want such a superficial explanation.

Describing my experience using words like "cerebral palsy" or "disability" might make others feel like they know what I'm talking about, but it doesn't convey the essence of what I experienced.

I need words that can more vividly and clearly reproduce what I have experienced.

And in this book, I want to write an explanation that will allow the reader to vaguely relate to my experiences of falling and still falling.

So, I want to drag you, the readers, along and fall together.

--- p.31~32

When we feel the sensation of 'my body moving', it is not because we receive feedback information from the body that actually moved.

Regardless of whether or not the movement actually occurred, the result of the movement simulation performed by the 'internal model' in the posterior parietal lobe is mistaken for the actual movement (this illusion is called 'false proprioception').

In this way, there exists an 'image' in the brain that projects the body and the external world.

This is called the 'internal model'.

Whether or not we actually move, our consciousness experiences our own intentions, movements, and changes in the world within a virtual reality created by computations of our internal models.

--- p.42

In this way, from a young age, I internalized an image of 'normal movement' that I could not perform on my own.

There is naturally a gap between the image of 'normal movement' produced in this way and the actual movement of my body.

Because of the desire of those around me to fill this gap, I had to undergo rehabilitation for over a decade since I was young to be able to perform 'non-disabled movements'.

--- p.69

The trainer's movements are performed completely independently of my movements, and the trainer cannot pick up the signals of fear or pain emanating from my body.

The trainer is an uncompromising hitter, a powerful hitter who wields power over my body.

Soon, my body succumbs to the trainer's power, as if losing territory to the enemy.

My arms, legs, and waist all gave way to the trainer's strength one by one, and I lost all tension.

However, this process does not have the same pleasure as the folding knife phenomenon.

Rather, it feels like I'm taking my arms, legs, and waist off my body and handing them over to a trainer.

--- p.87

Unlike the 'relationship of letting go and giving in' where you let go and let go, in a situation like the 'relationship of looking/being looked at', you feel anxious and your body gradually becomes stiff.

However, this process does not last forever.

The vicious cycle of impatience and stiffness soon leads me to the sensation of defeat, much like in the crawling forward competition, as my movements become increasingly disorganized and directionless.

And the energy that has built up inside me from anxiety and stiffness, when it crosses a certain point, my whole body periodically trembles in convulsions and disappears into thin air, and the coordination structure within my body suddenly loosens and my body becomes limp.

--- p.91

Perhaps it was at this time that I first realized that the self-image of a "weak and small me" that lends itself to sensual contrasts is not something that is given to me for free, but something that I must constantly monitor and regulate to maintain.

I didn't really care when I was in elementary school, but when I entered middle school, I suddenly started to care about how other people saw me, so I started dieting.

--- p.158

When you feel like you're about to deviate from the norm, your body becomes stiff, and when you deviate from the norm, your body relaxes.

There is a sensuality to the repetitive movements of stiffness and relaxation surrounding these norms.

We were trapped in that ‘world of our own’ and endlessly indulged in it.

Where is the other who will bring me the sensuality that opens up into a 'relationship of letting go and picking up each other', the other who will accept my strange movements...?

--- p.182

The moment I saw the renovated bathroom, my body slowly moved as if it was opening up.

It felt like I was tuning my body to a new toilet.

The toilet that had driven me to defeat last time was now reaching out to pick up my movements.

As if drawn by the hand of the toilet, my body slightly relaxed its internal coordination structure, and the resulting play enabled the restructuring, or tuning, of the internal coordination structure.

My body has changed as a result of the bathroom renovation.

--- p.203

The way you perceive the world when you're in a power wheelchair is completely different than when you're not.

Just being able to move quickly to various places reduces the gap with the outside world, and our sense of distance in space changes, as if objects or places that were previously unrelated to us suddenly become close.

As the amount of change in movement, and even the way the world is seen, increases, the passage of time also seems to accelerate.

As my options for action expand dramatically, my body image can feel more empowered.

In this way, the electric wheelchair completely changed my image of the world, including my body.

--- p.222~223

My own unique movements, completed in this way, often include the assistant's body as an essential element.

And between me and my assistant, a strong physical and extra-physical coordination structure, or teamwork, is established.

For example, a colleague who is accustomed to assisting me when drawing blood knows my body's movement patterns very well, so even without me expressing it verbally, he or she can sense the 'meaning' of the subtle movements of my fingertips and adjust the position of his or her hand supporting the patient's elbow.

It was a magical experience, as if my assistant and I had expanded into one large body.

When my assistant and I, two bodies, work together to perform the exercise of drawing blood from the same object, the patient's arm, it feels like the boundary between my body and my assistant's body becomes blurred.

--- p.237~238

I think that in a tense situation, the opportunity to breathe is a kind of sensual motivation to put aside the big picture goals for a moment and get to know each other's bodies through communication.

Rather than a 'relationship of looking/being looked at' that is obsessed with achieving a goal, a mindset that prioritizes a 'relationship of letting go and giving to each other' where the body opens up and one feels a kind of joy in the process of communicating with each other even if one fails to achieve the goal and is defeated allows one to accept each other's body image and creates a cooperative structure.

Then the stiff team will start to move slowly and eventually reach the goal, even if it takes a long way around.

--- p.244

Publisher's Review

Breaking free from the old myth of rehabilitation

Rejecting the norms of 'normal' body and movement

Until we become independent by forming a relationship of mutual support and being supported by others

Author Shinichiro Kumagaya was born with cerebral palsy due to brain damage caused by oxygen deprivation during childbirth.

Recalling the memories of pain and shame he experienced at the "rehabilitation camp" he attended every year as a child, a memory that dominated his childhood, he redefines his body, disability, and independence.

In rehabilitation camps, wheelchairs and assistive devices were prohibited and 'normal movements', i.e. 'movements of non-disabled people', were taught.

However, the disabled body has not acquired the stereotypical and normative movements of the 'normal body'.

After becoming an adult, the author broke away from the harsh and painful rehabilitation training that was tailored to the "normal" and "ideal" developmental process, using the "movements of non-disabled people" as a model, and began to live independently, creating his own movements and relationships with his surroundings. He has detailed this experience in his book.

The author explains his body, which easily becomes stiff and rigid, using the medical concept of 'coordination structure within the body' by exercise physiologist Nikolai Bernstein.

A body with cerebral palsy has excessive internal coordination, so its sensory and motor organs do not work in harmony, and it cannot perform 'normal movements'.

After starting to live independently, the author sought connections with objects and other people to supplement his movements, and named this 'extracorporeal coordination structure.'

It showed that even if a disabled body cannot perform the movements of a non-disabled person, independence is possible if coordination is achieved with surrounding objects/people.

The author uses a unique language to describe his own movements, which break away from the norm of 'normal movement' and become useless and meaningless, as 'not given' to others.

He also says that if we 'pick up' each other's movements and 'pick up' each other's movements, we will be able to be sufficiently independent even with bodies and movements that deviate from the norm.

As an example, the author details an anecdote about remodeling a bathroom in a house where he started living alone.

While in an unmodified bathroom, you feel 'rejected', when you use a bathroom that has been modified to fit your body and movements, you experience the bathroom 'picking up' your movements.

Through his experiences of walking in an electric wheelchair and working as a resident in a hospital, the author demonstrates that a body with a disability can actively compromise with objects and create its own movements that break away from the norm.

And, citing examples of cooperation with colleagues and caregivers during residency, he talks about how one can build a 'relationship of picking up and being picked up by others' as well as with objects.

The author vividly describes his experiences with the coercive and unequal process of repetitive rehabilitation treatment during his childhood, and sharply criticizes the history and context of rehabilitation treatment from a therapeutic/medical perspective that seeks to correct the disabled body and its movements from the perspective of the person involved.

It also contains the intense process of looking at one's own disabled body as it is and actively exploring ways to negotiate with the world and others, rather than trying to reach the 'movements of a non-disabled person' after starting independent living.

The body under observation, the sensuality of defeat, the freedom of incontinence, the experience of decline…

A strange and vivid sensuality and the politics of freedom

In rehabilitation camps, normative exercise goals were set to achieve 'non-disabled movement', and trainers continuously monitored the movements of the trainees undergoing training.

As a result, Trainee also internalized the trainer's perspective and began to try to realize movements that were not his own.

The author explains that the relationship between trainer and trainee has progressed from a 'relationship of picking up each other's movements' to a 'relationship of looking/being looked at', a 'relationship of perpetrator/victim'.

Trainee's body becomes more and more tense, her attempts to move fail, the trainer forcibly intervenes in Trainee's body, and eventually Trainee gradually loses strength and collapses, giving in.

The author says that he felt a strange sense of pleasure and sensuality as he went through this process repeatedly.

The most prominent concept in this book is ‘sensuality.’

The author names the pleasure felt when a disabled body is opened or released by a great force and loses tension as the 'sensuality of defeat.'

He confesses to having developed masochistic sexuality through his experiences with body manipulation in rehabilitation camps and in his daily life, and to having suffered from an eating disorder due to his desire to maintain a small and petite body.

These confessions also reveal the sexuality of the disabled person, while also demonstrating a desire for the safe sensuality that comes from a reciprocal, cooperative, and failure-accepting relationship, rather than the fearful sensuality that comes from a violent and one-sided relationship.

The author has long yearned for something that would accept his movements, something he could safely collapse into and surrender to.

The example of non-normative sensuality that the author focuses on most is the failure to 'defecate', 'incontinence', the first activity he attempted after leaving the world of rehabilitation and becoming independent.

The bizarre and raw narrative, which draws on Georges Bataille's concept of 'excretion' to describe the humiliation and ecstasy of a moment when one cannot overcome the urge to defecate without an assistant or a toilet that is tailored to one's body, has a strange power that draws readers in.

The author describes the moment of incontinence as a loss of connection with objects and people, and emphasizes that with a supportive partner or an environment tailored to one's body, one can be accepted and reconnected with the world.

In this way, the author shows the freedom that arises when we recognize something that is defined as “out of the norm” or “something that should not happen” as “something that is okay even if it deviates from the norm” or “something that can happen to anyone.”

Furthermore, by expanding our awareness of this liberating freedom, we broaden our thinking to include acceptance and recognition of the body as it gradually “deteriorates” as we age and develop secondary disabilities.

The author argues that not only people with disabilities, but all of us are declining beings, unable to perform 'normal' and normative movements forever, and therefore, we need to recognize the outside of the norm, actively cooperate with our surroundings and others, and attempt to create new movements.

Readers will immerse themselves in the author's vivid experiences of humiliation and bizarre sensuality, empathize with his constant attempts to interact with the world and others, and experience the freedom and liberation of breaking away from and reconnecting with "normal" norms.

‘Party research’ conducted from the perspective and body of the person involved,

The most radical exploration of independence and life for people with disabilities

Shinichiro Kumagaya is a leading researcher in the field of "personal research," in which people with disabilities or illnesses actively research their own disabilities and illnesses and consider becoming independent, rather than relying solely on doctors or social workers.

He currently serves as a professor at the University of Tokyo's Center for Advanced Science and Technology, where he conducts research on people with physical, mental, and developmental disabilities.

《Rehabilitation Night》 is the first work that enabled him to begin research on the subject.

In Korea, too, a critical movement toward non-disability-centeredness is becoming visible, and disability studies is having a huge impact on progressive movements and ideas.

Disability studies, in particular, is a major critical perspective on norms of normalcy and exclusion, and an important platform for discussing interdependence and relationships.

This book, which presents a new perspective on independence, dependence, normalcy, and treatment in Japan, a country with a long history of disability and rights movements, will likely become an important resource for Korean readers interested in disability studies.

It will also be able to provide radical new directions to professionals in areas such as rehabilitation therapy and activity support, which support and assist the movement and daily life of people with disabilities.

“What would happen if we accepted, claimed, and embraced our brokenness?” writes Eli Clare, a brain-impaired person and author, in Dazzlingly Imperfect.

Shinichiro Kumagaya demonstrates through his own experience how one can negotiate and interact with society with a body, movements, and desires that deviate from normal norms.

This book will confront readers with the non-ableist sentiments felt by people with disabilities and the fierce attempts to resist them, inviting us into a whole new world of liberation and sensuality.

Rejecting the norms of 'normal' body and movement

Until we become independent by forming a relationship of mutual support and being supported by others

Author Shinichiro Kumagaya was born with cerebral palsy due to brain damage caused by oxygen deprivation during childbirth.

Recalling the memories of pain and shame he experienced at the "rehabilitation camp" he attended every year as a child, a memory that dominated his childhood, he redefines his body, disability, and independence.

In rehabilitation camps, wheelchairs and assistive devices were prohibited and 'normal movements', i.e. 'movements of non-disabled people', were taught.

However, the disabled body has not acquired the stereotypical and normative movements of the 'normal body'.

After becoming an adult, the author broke away from the harsh and painful rehabilitation training that was tailored to the "normal" and "ideal" developmental process, using the "movements of non-disabled people" as a model, and began to live independently, creating his own movements and relationships with his surroundings. He has detailed this experience in his book.

The author explains his body, which easily becomes stiff and rigid, using the medical concept of 'coordination structure within the body' by exercise physiologist Nikolai Bernstein.

A body with cerebral palsy has excessive internal coordination, so its sensory and motor organs do not work in harmony, and it cannot perform 'normal movements'.

After starting to live independently, the author sought connections with objects and other people to supplement his movements, and named this 'extracorporeal coordination structure.'

It showed that even if a disabled body cannot perform the movements of a non-disabled person, independence is possible if coordination is achieved with surrounding objects/people.

The author uses a unique language to describe his own movements, which break away from the norm of 'normal movement' and become useless and meaningless, as 'not given' to others.

He also says that if we 'pick up' each other's movements and 'pick up' each other's movements, we will be able to be sufficiently independent even with bodies and movements that deviate from the norm.

As an example, the author details an anecdote about remodeling a bathroom in a house where he started living alone.

While in an unmodified bathroom, you feel 'rejected', when you use a bathroom that has been modified to fit your body and movements, you experience the bathroom 'picking up' your movements.

Through his experiences of walking in an electric wheelchair and working as a resident in a hospital, the author demonstrates that a body with a disability can actively compromise with objects and create its own movements that break away from the norm.

And, citing examples of cooperation with colleagues and caregivers during residency, he talks about how one can build a 'relationship of picking up and being picked up by others' as well as with objects.

The author vividly describes his experiences with the coercive and unequal process of repetitive rehabilitation treatment during his childhood, and sharply criticizes the history and context of rehabilitation treatment from a therapeutic/medical perspective that seeks to correct the disabled body and its movements from the perspective of the person involved.

It also contains the intense process of looking at one's own disabled body as it is and actively exploring ways to negotiate with the world and others, rather than trying to reach the 'movements of a non-disabled person' after starting independent living.

The body under observation, the sensuality of defeat, the freedom of incontinence, the experience of decline…

A strange and vivid sensuality and the politics of freedom

In rehabilitation camps, normative exercise goals were set to achieve 'non-disabled movement', and trainers continuously monitored the movements of the trainees undergoing training.

As a result, Trainee also internalized the trainer's perspective and began to try to realize movements that were not his own.

The author explains that the relationship between trainer and trainee has progressed from a 'relationship of picking up each other's movements' to a 'relationship of looking/being looked at', a 'relationship of perpetrator/victim'.

Trainee's body becomes more and more tense, her attempts to move fail, the trainer forcibly intervenes in Trainee's body, and eventually Trainee gradually loses strength and collapses, giving in.

The author says that he felt a strange sense of pleasure and sensuality as he went through this process repeatedly.

The most prominent concept in this book is ‘sensuality.’

The author names the pleasure felt when a disabled body is opened or released by a great force and loses tension as the 'sensuality of defeat.'

He confesses to having developed masochistic sexuality through his experiences with body manipulation in rehabilitation camps and in his daily life, and to having suffered from an eating disorder due to his desire to maintain a small and petite body.

These confessions also reveal the sexuality of the disabled person, while also demonstrating a desire for the safe sensuality that comes from a reciprocal, cooperative, and failure-accepting relationship, rather than the fearful sensuality that comes from a violent and one-sided relationship.

The author has long yearned for something that would accept his movements, something he could safely collapse into and surrender to.

The example of non-normative sensuality that the author focuses on most is the failure to 'defecate', 'incontinence', the first activity he attempted after leaving the world of rehabilitation and becoming independent.

The bizarre and raw narrative, which draws on Georges Bataille's concept of 'excretion' to describe the humiliation and ecstasy of a moment when one cannot overcome the urge to defecate without an assistant or a toilet that is tailored to one's body, has a strange power that draws readers in.

The author describes the moment of incontinence as a loss of connection with objects and people, and emphasizes that with a supportive partner or an environment tailored to one's body, one can be accepted and reconnected with the world.

In this way, the author shows the freedom that arises when we recognize something that is defined as “out of the norm” or “something that should not happen” as “something that is okay even if it deviates from the norm” or “something that can happen to anyone.”

Furthermore, by expanding our awareness of this liberating freedom, we broaden our thinking to include acceptance and recognition of the body as it gradually “deteriorates” as we age and develop secondary disabilities.

The author argues that not only people with disabilities, but all of us are declining beings, unable to perform 'normal' and normative movements forever, and therefore, we need to recognize the outside of the norm, actively cooperate with our surroundings and others, and attempt to create new movements.

Readers will immerse themselves in the author's vivid experiences of humiliation and bizarre sensuality, empathize with his constant attempts to interact with the world and others, and experience the freedom and liberation of breaking away from and reconnecting with "normal" norms.

‘Party research’ conducted from the perspective and body of the person involved,

The most radical exploration of independence and life for people with disabilities

Shinichiro Kumagaya is a leading researcher in the field of "personal research," in which people with disabilities or illnesses actively research their own disabilities and illnesses and consider becoming independent, rather than relying solely on doctors or social workers.

He currently serves as a professor at the University of Tokyo's Center for Advanced Science and Technology, where he conducts research on people with physical, mental, and developmental disabilities.

《Rehabilitation Night》 is the first work that enabled him to begin research on the subject.

In Korea, too, a critical movement toward non-disability-centeredness is becoming visible, and disability studies is having a huge impact on progressive movements and ideas.

Disability studies, in particular, is a major critical perspective on norms of normalcy and exclusion, and an important platform for discussing interdependence and relationships.

This book, which presents a new perspective on independence, dependence, normalcy, and treatment in Japan, a country with a long history of disability and rights movements, will likely become an important resource for Korean readers interested in disability studies.

It will also be able to provide radical new directions to professionals in areas such as rehabilitation therapy and activity support, which support and assist the movement and daily life of people with disabilities.

“What would happen if we accepted, claimed, and embraced our brokenness?” writes Eli Clare, a brain-impaired person and author, in Dazzlingly Imperfect.

Shinichiro Kumagaya demonstrates through his own experience how one can negotiate and interact with society with a body, movements, and desires that deviate from normal norms.

This book will confront readers with the non-ableist sentiments felt by people with disabilities and the fierce attempts to resist them, inviting us into a whole new world of liberation and sensuality.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: November 3, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 328 pages | 384g | 128*205*16mm

- ISBN13: 9788972971849

- ISBN10: 8972971847

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)