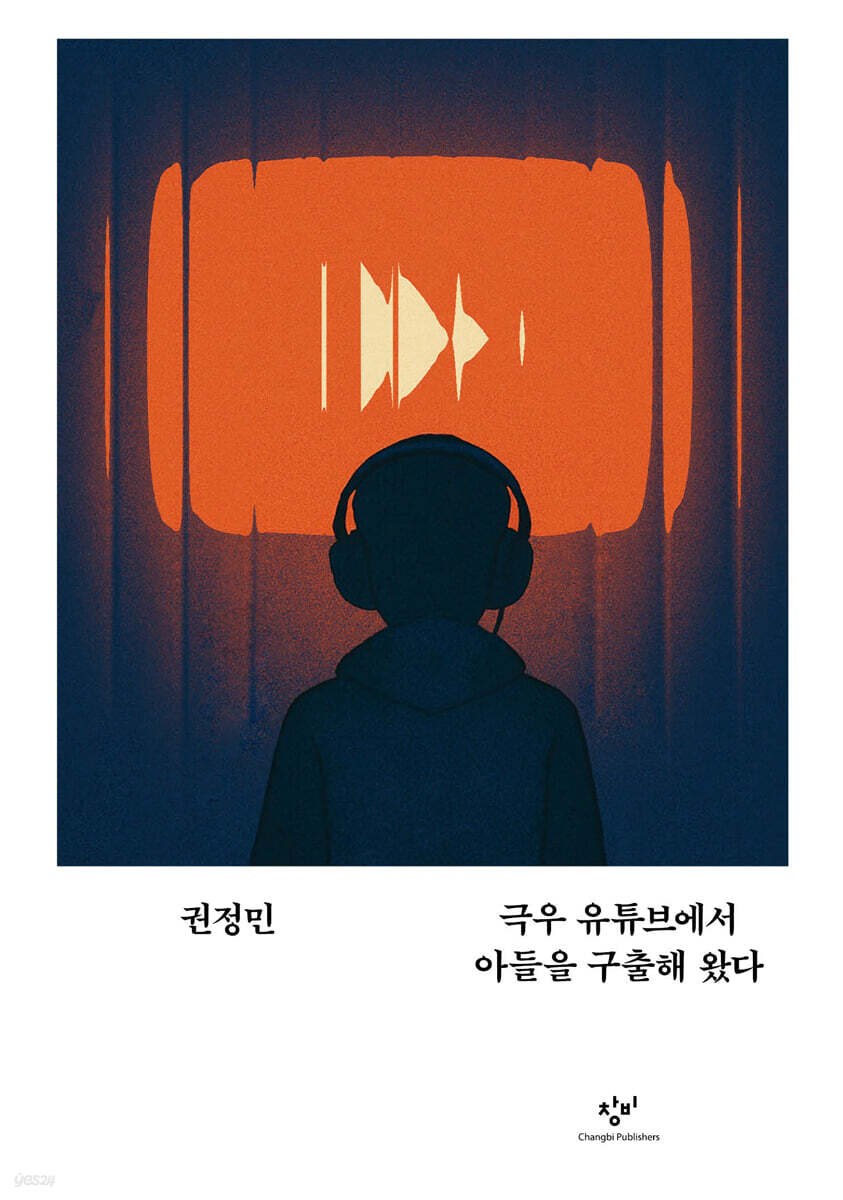

I rescued my son from a far-right YouTube channel.

|

Description

Book Introduction

Children who learn to hate,

The only chance to make things right is now.

Professor Kwon Jeong-min of Seoul National University reports

How to Talk to Your Child to Drive Extremism and Hate

What if our beloved child suddenly finds himself immersed in "far-right YouTube"? What if he casually spouts hateful remarks like, "Our country seems to discriminate against men too much," "Women should serve in the military too," "The Ministry of Gender Equality and Family should be abolished," and "Homosexuality is a disease"? Far-right worldviews have already become mainstream culture among young people.

Why do teenagers fall for content filled with anger and hostility?

How can we protect our children from violent and extremist thoughts?

Professor Kwon Jeong-min of Seoul National University, who sparked a heated debate in Korean society with his social media post titled "I rescued my son" the day after the riot at the Seoul Western District Court in January 2025, shares detailed tips on how to raise children who will not fall into extremism.

From how to answer your child's difficult questions to how to discuss controversial topics with your child, to tips for fostering healthy conversations and debates in everyday life, this book contains detailed advice from firsthand experience and an education expert for parents who are more concerned than ever.

In addition, it broadly portrays the current state of youth and the future of Korean society, including the process by which children fall into extremism, its cultural foundations, and even the crisis-ridden reality of education in South Korea and fundamental solutions.

A guide to wise democratic citizenship communication and parenting for both children and parents.

The only chance to make things right is now.

Professor Kwon Jeong-min of Seoul National University reports

How to Talk to Your Child to Drive Extremism and Hate

What if our beloved child suddenly finds himself immersed in "far-right YouTube"? What if he casually spouts hateful remarks like, "Our country seems to discriminate against men too much," "Women should serve in the military too," "The Ministry of Gender Equality and Family should be abolished," and "Homosexuality is a disease"? Far-right worldviews have already become mainstream culture among young people.

Why do teenagers fall for content filled with anger and hostility?

How can we protect our children from violent and extremist thoughts?

Professor Kwon Jeong-min of Seoul National University, who sparked a heated debate in Korean society with his social media post titled "I rescued my son" the day after the riot at the Seoul Western District Court in January 2025, shares detailed tips on how to raise children who will not fall into extremism.

From how to answer your child's difficult questions to how to discuss controversial topics with your child, to tips for fostering healthy conversations and debates in everyday life, this book contains detailed advice from firsthand experience and an education expert for parents who are more concerned than ever.

In addition, it broadly portrays the current state of youth and the future of Korean society, including the process by which children fall into extremism, its cultural foundations, and even the crisis-ridden reality of education in South Korea and fundamental solutions.

A guide to wise democratic citizenship communication and parenting for both children and parents.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

At the beginning of the book

I rescued my son from a far-right YouTube channel.

Black and White, and the 'Gray Area'

The goal of education should be a happy life.

The process of falling into extremism

Questions I received from my son one day

How to Discuss Extremism with a Child

Don't be afraid that your parents don't have a clear answer.

Still, there is value that cannot be turned down.

Debate is a democratic lifestyle

Finding material for conversation and discussion in everyday life

To cultivate citizens of a new era

In conclusion

Q&A

Sentences I want to remember

I rescued my son from a far-right YouTube channel.

Black and White, and the 'Gray Area'

The goal of education should be a happy life.

The process of falling into extremism

Questions I received from my son one day

How to Discuss Extremism with a Child

Don't be afraid that your parents don't have a clear answer.

Still, there is value that cannot be turned down.

Debate is a democratic lifestyle

Finding material for conversation and discussion in everyday life

To cultivate citizens of a new era

In conclusion

Q&A

Sentences I want to remember

Detailed image

Into the book

On January 19, 2025, a riot broke out at the Seoul Western District Court.

The mob stormed the courthouse, occupied it, destroyed the building and its facilities, and engaged in violence against police, civilians, and journalists.

Things like this riot must never happen again.

I don't want to leave that kind of world to my children.

I already have a feeling it's too late.

But even now, we must do something.

We must protect our children from extremism and fascism.

Let's check in with our children right now and talk about what they watch on YouTube so they don't become people who commit such crimes.

We must guide children to become sound, sensible, and democratic citizens.

This is our responsibility now.

---From "Introduction"

Why should we worry about this? Our sole purpose is to ensure that, as parents, our children live happy lives.

Parents truly hope that their children will not live unhappy lives mired in violence and hatred toward others, that they will understand the misaligned discontent with the world and the resulting suffering without having to experience it firsthand, and that they will be able to make wise choices and decisions that lead to happy outcomes.

That's why our children need a good education.

Even if you memorize textbooks and workbooks and get good grades on tests, if you live with hatred and disregard for others, that life will ultimately lead to unhappiness.

We don't want to dictate political affiliations to our children.

I want to teach our children the wisdom to live happily.

Because I love you.

--- p.24~25

When you have extremist thoughts, you often express hatred towards a specific group.

However, parents are uncomfortable or avoid talking to their children about issues of hatred toward socially vulnerable groups such as women, sexual minorities, and the disabled.

Contrary to what parents might think, it's actually necessary to have open and honest conversations with children about hate.

We must instill a clear value that hate is wrong.

As I've said before, I think the gray area in our lives is very large.

I think sometimes good can become evil and evil can become good, depending on the circumstances.

There are many times when you have to make different judgments depending on the situation.

But there is a line that must not be crossed.

It is ‘hate’ and ‘exclusion’.

--- p.58

Democracy isn't built overnight.

Internalizing democracy into our lives requires continuous practice.

The best way to practice is through conversation and discussion.

The act of debate itself is a process of training democratic attitudes.

Listening to and respecting the opinions of others, acknowledging differences without rejecting them, and finding common understanding.

Furthermore, it is a process of achieving coexistence and agreement through continuous dialogue with people with different opinions on issues for which there is no right answer.

This is the democratic lifestyle.

--- p.66

Change doesn't come from huge events, but from the very small conversations and questions we have every day.

We must teach children how to criticize, question, and reflect on social problems.

The small conversations we have with our children at home can go a long way toward helping them grow and ultimately making our society a healthier place.

Keep asking open-ended questions like, “What are you thinking?” or “What would you like to see happen in the world?”

Rather than unilaterally evaluating your child's answers as "right/wrong" or "good/bad," continue the conversation by asking and answering questions.

When our small discussions come together, this society will change.

The mob stormed the courthouse, occupied it, destroyed the building and its facilities, and engaged in violence against police, civilians, and journalists.

Things like this riot must never happen again.

I don't want to leave that kind of world to my children.

I already have a feeling it's too late.

But even now, we must do something.

We must protect our children from extremism and fascism.

Let's check in with our children right now and talk about what they watch on YouTube so they don't become people who commit such crimes.

We must guide children to become sound, sensible, and democratic citizens.

This is our responsibility now.

---From "Introduction"

Why should we worry about this? Our sole purpose is to ensure that, as parents, our children live happy lives.

Parents truly hope that their children will not live unhappy lives mired in violence and hatred toward others, that they will understand the misaligned discontent with the world and the resulting suffering without having to experience it firsthand, and that they will be able to make wise choices and decisions that lead to happy outcomes.

That's why our children need a good education.

Even if you memorize textbooks and workbooks and get good grades on tests, if you live with hatred and disregard for others, that life will ultimately lead to unhappiness.

We don't want to dictate political affiliations to our children.

I want to teach our children the wisdom to live happily.

Because I love you.

--- p.24~25

When you have extremist thoughts, you often express hatred towards a specific group.

However, parents are uncomfortable or avoid talking to their children about issues of hatred toward socially vulnerable groups such as women, sexual minorities, and the disabled.

Contrary to what parents might think, it's actually necessary to have open and honest conversations with children about hate.

We must instill a clear value that hate is wrong.

As I've said before, I think the gray area in our lives is very large.

I think sometimes good can become evil and evil can become good, depending on the circumstances.

There are many times when you have to make different judgments depending on the situation.

But there is a line that must not be crossed.

It is ‘hate’ and ‘exclusion’.

--- p.58

Democracy isn't built overnight.

Internalizing democracy into our lives requires continuous practice.

The best way to practice is through conversation and discussion.

The act of debate itself is a process of training democratic attitudes.

Listening to and respecting the opinions of others, acknowledging differences without rejecting them, and finding common understanding.

Furthermore, it is a process of achieving coexistence and agreement through continuous dialogue with people with different opinions on issues for which there is no right answer.

This is the democratic lifestyle.

--- p.66

Change doesn't come from huge events, but from the very small conversations and questions we have every day.

We must teach children how to criticize, question, and reflect on social problems.

The small conversations we have with our children at home can go a long way toward helping them grow and ultimately making our society a healthier place.

Keep asking open-ended questions like, “What are you thinking?” or “What would you like to see happen in the world?”

Rather than unilaterally evaluating your child's answers as "right/wrong" or "good/bad," continue the conversation by asking and answering questions.

When our small discussions come together, this society will change.

--- p.68~69

Publisher's Review

“Children who learn to hate

“Now is the only chance to make things right.”

Professor Kwon Jeong-min of Seoul National University reports

How to Talk to Your Child to Drive Extremism and Hate

What if our beloved child suddenly finds himself immersed in "far-right YouTube"? What if he casually spouts hate speech and extremist rhetoric like, "The Ministry of Gender Equality and Family should be abolished," "Homosexuality is a disease," and "Martial law is romantic." The far-right worldview has already become a mainstream cultural phenomenon among young people.

Why do teenagers fall for content filled with anger and hostility?

How can we protect our children from violent and extremist ideas?

Professor Kwon Jeong-min of Seoul National University, who created a heated debate in Korean society with his post on social media the day after the riot at the Seoul Western District Court in January 2025 titled "I rescued my son," shares detailed tips on how to raise children who will not fall into extremism in his new book, "I rescued my son from far-right YouTube."

From how to deal with your child's difficult questions to how to talk to your child about controversial topics and tips for fostering healthy discussions in everyday life, this book contains first-hand experience and advice from an education expert, designed for parents who are more concerned than ever.

In addition, it broadly discusses the process by which children fall into extremism, its cultural foundations, the crisis-ridden reality of education in South Korea, and fundamental solutions, diagnosing the current state of youth issues and envisioning the future of our society.

A smart guide to democratic citizenship communication and parenting for both children and parents.

“My child has become far-right.”

A mother's confession that swept social media

On January 19, 2025, a riot broke out at the Seoul Western District Court.

The mob stormed the courthouse, occupied it, destroyed the building and its facilities, and engaged in violence against police, civilians, and journalists.

The fact that this mob included teenagers has raised deep concerns.

Unfortunately, the extremist thoughts and actions of young people are not limited to the deviant behavior of just one or two individuals.

In online communities where male users in their teens and twenties are the main users, there are many posts praising a candidate who made misogynistic remarks without filtering them during the last presidential TV debate, saying, "He said the right thing."

In school classrooms, discriminatory and hateful remarks against minorities, such as “Eradicate feminism,” “As expected from a black person,” and “Are you gay too?” have long become common memes.

The term "MH Generation" is even used to describe a generation that has been exposed to ridicule and disparagement of former President Roh Moo-hyun since childhood.

The day after the riot at the Western District Court, Professor Kwon Jeong-min of the Department of Early Childhood and Special Education at Seoul National University of Education posted on his social media, “I rescued my son,” bringing the reality of youth extreme right-wing extremism to public attention. This post immediately became a hot topic online.

The author's confession that her son, whom she thought could not be educated better, "became addicted to far-right YouTube in an instant" (page 6) and that "almost all the boys around my high school son" (page 8) believe in far-right ideology, resonated with not only parents of adolescent children but also citizens concerned about the future of democracy, recording an astonishing 1,400 shares.

There was also a flood of requests from people struggling with the same problem and not knowing what to do, as well as from people asking for help in rescuing their families from extremism.

This is Professor Kwon Jeong-min's thoughtful and sincere response to readers' earnest inquiries about his new book, "I Rescued My Son from Far-Right YouTube."

A child who cannot think for himself

Falling into hatred and extremism

The author identifies YouTube, online communities, and a vulnerable environment within peer culture as the main factors that lead children to fall into hatred and extremism.

“Users in gaming communities use derogatory and abusive language toward former presidents” (page 27) as a common joke, or “muscular YouTubers show off their bodies while promoting sexual prejudices such as ‘men should be like this since ancient times, women should be like that’” (page 27) are all too common these days.

Hate speech that worships masculinity, glorifies dictatorship and martial law, is anti-feminist, and disparages minorities is packaged as a “cool and fun meme” in the content of far-right YouTubers and influencers.

Social media and YouTube algorithms expose children to more provocative content to generate revenue, and children naturally internalize this.

Even when hateful remarks are made among friends, “they are unable to actively stop them for fear of ruining their relationships with friends or making the atmosphere awkward” (p. 33).

In this atmosphere, children come to accept extremist speech and behavior as 'socially acceptable and normal culture.'

At the root of this entire process of youth becoming more extreme is the 'lack of education that allows them to think for themselves.'

The author points out that our country's education system, which is centered on entrance exams and is "nothing more than a game of guessing the right answer" (p. 22), is losing the ability to critically view and judge content in an educational environment that does not even give children time to think or the opportunity to ask questions.

We're so used to chasing the established correct answer that we simply accept and nod to the extremist claims we see on YouTube or from our friends without being able to question them by asking, "Is that really true?" or "Why do you think that?"

In this age of content overload and AI replacing human domains, the author emphasizes the importance of "critical thinking skills," and powerfully conveys his insight as an educator that "children who know how to ask questions and think for themselves will not lose their way" (p. 101).

Drawn from vivid experience and proven knowledge

How to Reclaim Healthy Communication with Your Child

Although YouTube has become a conduit for propagating far-right ideology, the author acknowledges the reality, saying, “That doesn’t mean YouTube itself can be banned today” (p. 84).

Instead, I recommend guiding children to develop critical thinking skills, such as “self-filtering” (p. 84), so that they can independently determine whether something is morally correct, factually accurate, or logically flawed.

The solution the author proposes is ‘dialogue and discussion.’

It may not seem like anything special, but the closer you are to family, the more unfamiliar and awkward honest conversations and discussions can be.

Professor Kwon Jeong-min shares detailed conversation techniques that anyone can emulate at home and in schools, drawing on his vivid experience of "rescuing his son from a far-right YouTube channel."

If your child suddenly starts making extremist claims, simply fact-checking the information online can help resolve the misunderstanding more easily than you might expect.

If the child is deeply immersed in hateful thoughts, you can gradually broaden the child's perspective on the world by having several conversations based on the four-step discussion method of ① listening first, ② empathizing with the child's point of view, ③ connecting the issue to stories around them, and ④ gradually introducing new information.

Tips for facilitating communication with your children in everyday life, such as not being afraid to say, "I don't know," cultivating empathy by capturing their interests, and teaching empathy and tolerance by watching the news together, are also very useful.

The author emphasizes that, “If I had to pick one thing that is most important, it would be to enjoy the very act of talking with your child” (p. 53).

There are no set answers or predetermined boundaries when it comes to conversations with children.

Within a relationship of love and trust, the ability to refine and express one's thoughts regardless of the topic, listen to the other person's story, and empathize with the situation of others is accumulated and only then can the 'power of thinking' be cultivated.

And this power of thought is the frontline measure to prevent extremism from spreading in children's minds and Korean society, and it becomes the "root of democracy" (p. 83).

Change “does not come from huge events, but from the very small conversations and questions we have every day” (p. 68).

Perhaps the greatest gift we can give our children today is to cultivate the courage to challenge a culture of hate and extremism, the wisdom to think, question, and engage in dialogue, and the citizenship to understand the complexity of the world and discern right from wrong.

“Now is the only chance to make things right.”

Professor Kwon Jeong-min of Seoul National University reports

How to Talk to Your Child to Drive Extremism and Hate

What if our beloved child suddenly finds himself immersed in "far-right YouTube"? What if he casually spouts hate speech and extremist rhetoric like, "The Ministry of Gender Equality and Family should be abolished," "Homosexuality is a disease," and "Martial law is romantic." The far-right worldview has already become a mainstream cultural phenomenon among young people.

Why do teenagers fall for content filled with anger and hostility?

How can we protect our children from violent and extremist ideas?

Professor Kwon Jeong-min of Seoul National University, who created a heated debate in Korean society with his post on social media the day after the riot at the Seoul Western District Court in January 2025 titled "I rescued my son," shares detailed tips on how to raise children who will not fall into extremism in his new book, "I rescued my son from far-right YouTube."

From how to deal with your child's difficult questions to how to talk to your child about controversial topics and tips for fostering healthy discussions in everyday life, this book contains first-hand experience and advice from an education expert, designed for parents who are more concerned than ever.

In addition, it broadly discusses the process by which children fall into extremism, its cultural foundations, the crisis-ridden reality of education in South Korea, and fundamental solutions, diagnosing the current state of youth issues and envisioning the future of our society.

A smart guide to democratic citizenship communication and parenting for both children and parents.

“My child has become far-right.”

A mother's confession that swept social media

On January 19, 2025, a riot broke out at the Seoul Western District Court.

The mob stormed the courthouse, occupied it, destroyed the building and its facilities, and engaged in violence against police, civilians, and journalists.

The fact that this mob included teenagers has raised deep concerns.

Unfortunately, the extremist thoughts and actions of young people are not limited to the deviant behavior of just one or two individuals.

In online communities where male users in their teens and twenties are the main users, there are many posts praising a candidate who made misogynistic remarks without filtering them during the last presidential TV debate, saying, "He said the right thing."

In school classrooms, discriminatory and hateful remarks against minorities, such as “Eradicate feminism,” “As expected from a black person,” and “Are you gay too?” have long become common memes.

The term "MH Generation" is even used to describe a generation that has been exposed to ridicule and disparagement of former President Roh Moo-hyun since childhood.

The day after the riot at the Western District Court, Professor Kwon Jeong-min of the Department of Early Childhood and Special Education at Seoul National University of Education posted on his social media, “I rescued my son,” bringing the reality of youth extreme right-wing extremism to public attention. This post immediately became a hot topic online.

The author's confession that her son, whom she thought could not be educated better, "became addicted to far-right YouTube in an instant" (page 6) and that "almost all the boys around my high school son" (page 8) believe in far-right ideology, resonated with not only parents of adolescent children but also citizens concerned about the future of democracy, recording an astonishing 1,400 shares.

There was also a flood of requests from people struggling with the same problem and not knowing what to do, as well as from people asking for help in rescuing their families from extremism.

This is Professor Kwon Jeong-min's thoughtful and sincere response to readers' earnest inquiries about his new book, "I Rescued My Son from Far-Right YouTube."

A child who cannot think for himself

Falling into hatred and extremism

The author identifies YouTube, online communities, and a vulnerable environment within peer culture as the main factors that lead children to fall into hatred and extremism.

“Users in gaming communities use derogatory and abusive language toward former presidents” (page 27) as a common joke, or “muscular YouTubers show off their bodies while promoting sexual prejudices such as ‘men should be like this since ancient times, women should be like that’” (page 27) are all too common these days.

Hate speech that worships masculinity, glorifies dictatorship and martial law, is anti-feminist, and disparages minorities is packaged as a “cool and fun meme” in the content of far-right YouTubers and influencers.

Social media and YouTube algorithms expose children to more provocative content to generate revenue, and children naturally internalize this.

Even when hateful remarks are made among friends, “they are unable to actively stop them for fear of ruining their relationships with friends or making the atmosphere awkward” (p. 33).

In this atmosphere, children come to accept extremist speech and behavior as 'socially acceptable and normal culture.'

At the root of this entire process of youth becoming more extreme is the 'lack of education that allows them to think for themselves.'

The author points out that our country's education system, which is centered on entrance exams and is "nothing more than a game of guessing the right answer" (p. 22), is losing the ability to critically view and judge content in an educational environment that does not even give children time to think or the opportunity to ask questions.

We're so used to chasing the established correct answer that we simply accept and nod to the extremist claims we see on YouTube or from our friends without being able to question them by asking, "Is that really true?" or "Why do you think that?"

In this age of content overload and AI replacing human domains, the author emphasizes the importance of "critical thinking skills," and powerfully conveys his insight as an educator that "children who know how to ask questions and think for themselves will not lose their way" (p. 101).

Drawn from vivid experience and proven knowledge

How to Reclaim Healthy Communication with Your Child

Although YouTube has become a conduit for propagating far-right ideology, the author acknowledges the reality, saying, “That doesn’t mean YouTube itself can be banned today” (p. 84).

Instead, I recommend guiding children to develop critical thinking skills, such as “self-filtering” (p. 84), so that they can independently determine whether something is morally correct, factually accurate, or logically flawed.

The solution the author proposes is ‘dialogue and discussion.’

It may not seem like anything special, but the closer you are to family, the more unfamiliar and awkward honest conversations and discussions can be.

Professor Kwon Jeong-min shares detailed conversation techniques that anyone can emulate at home and in schools, drawing on his vivid experience of "rescuing his son from a far-right YouTube channel."

If your child suddenly starts making extremist claims, simply fact-checking the information online can help resolve the misunderstanding more easily than you might expect.

If the child is deeply immersed in hateful thoughts, you can gradually broaden the child's perspective on the world by having several conversations based on the four-step discussion method of ① listening first, ② empathizing with the child's point of view, ③ connecting the issue to stories around them, and ④ gradually introducing new information.

Tips for facilitating communication with your children in everyday life, such as not being afraid to say, "I don't know," cultivating empathy by capturing their interests, and teaching empathy and tolerance by watching the news together, are also very useful.

The author emphasizes that, “If I had to pick one thing that is most important, it would be to enjoy the very act of talking with your child” (p. 53).

There are no set answers or predetermined boundaries when it comes to conversations with children.

Within a relationship of love and trust, the ability to refine and express one's thoughts regardless of the topic, listen to the other person's story, and empathize with the situation of others is accumulated and only then can the 'power of thinking' be cultivated.

And this power of thought is the frontline measure to prevent extremism from spreading in children's minds and Korean society, and it becomes the "root of democracy" (p. 83).

Change “does not come from huge events, but from the very small conversations and questions we have every day” (p. 68).

Perhaps the greatest gift we can give our children today is to cultivate the courage to challenge a culture of hate and extremism, the wisdom to think, question, and engage in dialogue, and the citizenship to understand the complexity of the world and discern right from wrong.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: July 11, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 124 pages | 176g | 128*182*11mm

- ISBN13: 9788936480844

- ISBN10: 8936480847

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)