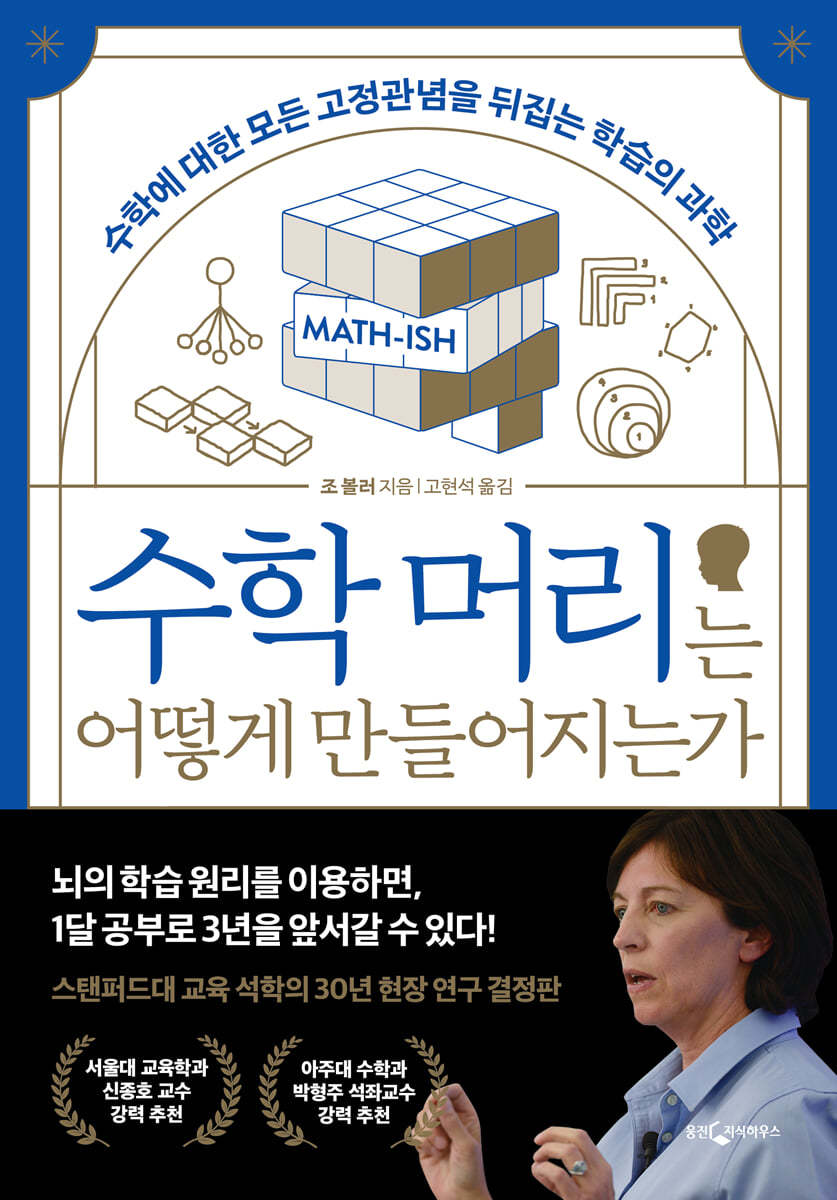

How Math Brains Are Made

|

Description

Book Introduction

A math study that makes you understand three years of learning in one month.

Anyone can do it by using the brain's learning principles!

★The definitive edition of 30 years of field research by a world-renowned education scholar.

★Recommended by Professor Shin Jong-ho of the Department of Education at Seoul National University and Professor Park Hyeong-ju of the Department of Mathematics at Ajou University

Why do children hate math? Is there a way to help them excel at it? "How Math Aptitude Is Developed" offers a useful guide to many parents' concerns.

The author, Stanford University professor Joe Boller, is a world-renowned scholar who has studied mathematics education for over 30 years and is considered one of “the most innovative and creative educators today” who crosses the boundaries of brain science, psychology, and education.

The reason why math is difficult and we don't want to do it is because our brains are not learning in a fun and effective way during math classes.

This book, based on cutting-edge science like mindset and metacognition, provides concrete, practical methods to transform your child's mathematical potential into a real-world math whiz.

It is wrong to say that only a few children are naturally good at math.

"How to Build a Math Brain" refutes various misconceptions and prejudices about studying math with data, guiding readers to the most effective path for anyone to enjoy learning high-level math.

“Joe Boller’s weapon is a massive amount of scientific data.

“If you ignore his groundbreaking research and amazing discoveries, you and your children will not be able to survive in the 21st century.” _Keith Devlin, Professor Emeritus of Mathematics, Stanford University

Anyone can do it by using the brain's learning principles!

★The definitive edition of 30 years of field research by a world-renowned education scholar.

★Recommended by Professor Shin Jong-ho of the Department of Education at Seoul National University and Professor Park Hyeong-ju of the Department of Mathematics at Ajou University

Why do children hate math? Is there a way to help them excel at it? "How Math Aptitude Is Developed" offers a useful guide to many parents' concerns.

The author, Stanford University professor Joe Boller, is a world-renowned scholar who has studied mathematics education for over 30 years and is considered one of “the most innovative and creative educators today” who crosses the boundaries of brain science, psychology, and education.

The reason why math is difficult and we don't want to do it is because our brains are not learning in a fun and effective way during math classes.

This book, based on cutting-edge science like mindset and metacognition, provides concrete, practical methods to transform your child's mathematical potential into a real-world math whiz.

It is wrong to say that only a few children are naturally good at math.

"How to Build a Math Brain" refutes various misconceptions and prejudices about studying math with data, guiding readers to the most effective path for anyone to enjoy learning high-level math.

“Joe Boller’s weapon is a massive amount of scientific data.

“If you ignore his groundbreaking research and amazing discoveries, you and your children will not be able to survive in the 21st century.” _Keith Devlin, Professor Emeritus of Mathematics, Stanford University

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Chapter 1: Building a New Relationship with Mathematicsㆍ9

A Different Approach / Mathematics in a Narrow Sense / The Pervasive Cultural Issue / The Link Between Mindset and Cognition / A New Learning Model for Success

Chapter 2: Learning How to Learnㆍ39

Metacognition, a new cognitive theory / Practical applications of metacognition / 8 math learning strategies that promote metacognition / Journal writing / Building a reflection and growth mindset / How to promote metacognition through group work: Teaching people to respect each other's thinking / What assessments encourage metacognition?

Chapter 3: Developing a Growth Mindsetㆍ85

Why We Should Love Effort / How to Get Children on the Effort Bus

Chapter 4: Real Mathematics in the Worldㆍ123

Learning and Teaching What Matters / Core Area 1: Number Sense / Core Area 2: Data Literacy / Core Area 3: Linear Equations / The Usefulness of Mathematics: Data Recognition

Chapter 5: Mathematics as a Visual Experienceㆍ175

Mental Representation / Neuroscience of Mental Representation / Grouping / Mathematically Diverse Operations

Chapter 6: Connecting Mathematical Conceptsㆍ225

The key is number sense / standard problems / mathematical connections / teaching concepts and connections / success linked to conceptual education

Chapter 7: Redesigning Practice and Feedbackㆍ267

What is varied and deliberate practice? / Examples of practice in various ways / See more / Procedural and conceptual problems / Applying variety to math examples / Assessment through feedback loops / Teaching using feedback loops

Chapter 8: The Future of New Mathematics Studiesㆍ303

A New Model for Equity and Professionalism / Diverse Participation Through Data Research / The Impact of One Teacher / Upending the Status Quo in Mathematics / Systemic Racism and Bias / Five Principles for Effective Change

Acknowledgements

main

A Different Approach / Mathematics in a Narrow Sense / The Pervasive Cultural Issue / The Link Between Mindset and Cognition / A New Learning Model for Success

Chapter 2: Learning How to Learnㆍ39

Metacognition, a new cognitive theory / Practical applications of metacognition / 8 math learning strategies that promote metacognition / Journal writing / Building a reflection and growth mindset / How to promote metacognition through group work: Teaching people to respect each other's thinking / What assessments encourage metacognition?

Chapter 3: Developing a Growth Mindsetㆍ85

Why We Should Love Effort / How to Get Children on the Effort Bus

Chapter 4: Real Mathematics in the Worldㆍ123

Learning and Teaching What Matters / Core Area 1: Number Sense / Core Area 2: Data Literacy / Core Area 3: Linear Equations / The Usefulness of Mathematics: Data Recognition

Chapter 5: Mathematics as a Visual Experienceㆍ175

Mental Representation / Neuroscience of Mental Representation / Grouping / Mathematically Diverse Operations

Chapter 6: Connecting Mathematical Conceptsㆍ225

The key is number sense / standard problems / mathematical connections / teaching concepts and connections / success linked to conceptual education

Chapter 7: Redesigning Practice and Feedbackㆍ267

What is varied and deliberate practice? / Examples of practice in various ways / See more / Procedural and conceptual problems / Applying variety to math examples / Assessment through feedback loops / Teaching using feedback loops

Chapter 8: The Future of New Mathematics Studiesㆍ303

A New Model for Equity and Professionalism / Diverse Participation Through Data Research / The Impact of One Teacher / Upending the Status Quo in Mathematics / Systemic Racism and Bias / Five Principles for Effective Change

Acknowledgements

main

Detailed image

Into the book

For centuries, most people have assumed that some people are born with a mathematical brain and are good at math, while others are not.

But over the past decade, it has become increasingly clear that there is no such thing as a math brain, and that all types of brain function are continually developing, connecting, and changing.

In most countries around the world, between 10 and 40 percent of people live their lives avoiding math as much as possible.

Many of these math-disadvantaged individuals live in poverty, and inequalities in the education system and society prevent them from accessing learning opportunities and improving their lives.

On the other hand, students with high math achievement are more likely to escape poverty and have better lives.

The possibility of becoming rich also increases.

--- From "Chapter 1: Building a New Relationship with Mathematics"

Teachers I've worked with tell me that instead of assigning meaningless homework, they give students homework that involves reflecting on the material in class, which improves their mathematical understanding.

This method is very effective because it provides students with an invaluable opportunity to reflect on their knowledge and understanding.

--- From "Learning How to Learn Chapter 2"

When I teach students at camp, I tell them, “I give you difficult assignments because I want you to try.

“We give you challenging tasks to train your brain,” he says.

This gives students freedom.

This way, students will know that difficult times are productive times and will work more persistently to solve problems.

--- From "Chapter 3: Equipping a Growth Mindset"

It is problematic to introduce rules that students do not understand.

Elementary school teachers have a vital role to play in helping students develop number sense and, more generally, understand mathematical ideas using meaningful visual and physical representations.

But teaching rules seems to halt students' sensory development.

--- From "Chapter 5 Mathematics as a Visual Experience"

While traditional notebook writing, where ideas are written down, only involves superficial processing of information, sketching requires a range of valuable learning activities, including information processing, big-picture thinking, visualization, and restructuring.

Research shows that when students sketch their ideas in a sketchnote, their achievement, engagement, and motivation in solving word-based math problems increase, especially for students experiencing learning gaps.

But over the past decade, it has become increasingly clear that there is no such thing as a math brain, and that all types of brain function are continually developing, connecting, and changing.

In most countries around the world, between 10 and 40 percent of people live their lives avoiding math as much as possible.

Many of these math-disadvantaged individuals live in poverty, and inequalities in the education system and society prevent them from accessing learning opportunities and improving their lives.

On the other hand, students with high math achievement are more likely to escape poverty and have better lives.

The possibility of becoming rich also increases.

--- From "Chapter 1: Building a New Relationship with Mathematics"

Teachers I've worked with tell me that instead of assigning meaningless homework, they give students homework that involves reflecting on the material in class, which improves their mathematical understanding.

This method is very effective because it provides students with an invaluable opportunity to reflect on their knowledge and understanding.

--- From "Learning How to Learn Chapter 2"

When I teach students at camp, I tell them, “I give you difficult assignments because I want you to try.

“We give you challenging tasks to train your brain,” he says.

This gives students freedom.

This way, students will know that difficult times are productive times and will work more persistently to solve problems.

--- From "Chapter 3: Equipping a Growth Mindset"

It is problematic to introduce rules that students do not understand.

Elementary school teachers have a vital role to play in helping students develop number sense and, more generally, understand mathematical ideas using meaningful visual and physical representations.

But teaching rules seems to halt students' sensory development.

--- From "Chapter 5 Mathematics as a Visual Experience"

While traditional notebook writing, where ideas are written down, only involves superficial processing of information, sketching requires a range of valuable learning activities, including information processing, big-picture thinking, visualization, and restructuring.

Research shows that when students sketch their ideas in a sketchnote, their achievement, engagement, and motivation in solving word-based math problems increase, especially for students experiencing learning gaps.

--- From "Chapter 6 Connecting Mathematical Concepts"

Publisher's Review

"Daksu (Stop Math)" is ruining children's math skills.

The Secrets of Learning and Growth: A Cross-Cultural Approach to Neuroscience, Psychology, and Education

As the number of parents hoping their children will pursue medical studies increases, the craze for 'early math education' is heating up.

In Daechi-dong, it is common for children to start learning 'Daksu' (short for 'Dakchigo Math') from the age of 4.

Given this situation, the word 'supoja' (short for 'math giver'), which was used among middle and high school students in the past, has come down to elementary school.

According to a survey, one in eight elementary school students consider themselves to be a "student dropout."

But honestly, adults know better why kids hate math.

Because I experienced it firsthand.

The blackboard is filled with numbers and symbols whose meanings are unknown.

After the one-sided problem-solving lecture, you now have to quickly solve the problem within the time limit and get the correct answer.

The score doesn't reflect any of my effort or interest.

How many people can possibly enjoy math like this? Ultimately, for most, math class remains a "terrible" experience.

Does math have to be taught this way? Are there better methods? Parents who harbor these doubts will be amazed by the new math study method introduced in "How Math Brains Are Developed."

The author, Stanford University professor Joe Boller, has been researching learning conditions that can unleash mathematical potential for the past 30 years, working across neuroscience, psychology, and education.

And we share with teachers and parents around the world learning methods and examples that have been successful in improving the math achievement of students of all ages, levels, and races.

Neither the child nor the math is at fault.

The problem is the wrong study method.

Many people think that math is something you are born with.

Representative examples include statements like, ‘I’m not good at math’ or ‘I’m not suited for math.’

But neuroscience research shows that our brains are not fixed, but are constantly changing and growing.

In other words, we find math difficult and difficult to understand because we are not studying in a way that allows our brains to learn effectively.

Let's think back to the division of fractions we learned in elementary school.

Teachers constantly drill students into the "flip and multiply" method, but rarely explain why they should do it.

Children who learn and memorize only the rules that produce answers quickly and accurately are bound to get lost in the ever-growing list of formulas as they progress.

When young children first learn addition, it takes up a lot of space in their brains.

This knowledge becomes compressed over the years, taking up less and less physical space in the brain.

So when you're asked to do 3+4 as an adult, you can quickly and easily retrieve that knowledge in a compressed, small space.

This compression creates more and more learning space in our brains.

But Gray and Toll, in their landmark paper, argue that we can only compress concepts.

If children only learn the rules and methods, compression will not occur at all.

(Page 230)

The practice of constantly testing children to see if they have learned properly can also have a negative impact on learning.

This makes children believe that the essence of math is getting the right answer.

As a result, children who have experienced repeated failures in assessments and tests naturally conclude that they do not have mathematical talent or aptitude and give up.

Scientists have found that when people with math anxiety are presented with math problems, their fear centers in the brain activate, much like when they see snakes or spiders.

Fear and anxiety disable parts of the brain, including the hippocampus, which impairs learning ability.

On the other hand, there is a considerable amount of research showing that positive thoughts and beliefs about math activate these important parts of the brain, which improves learning ability and achievement.

(Page 33)

Our brain is not a computer that outputs what it inputs.

Knowledge that is not actively reconstructed in the mind is prone to evaporation, and learning attitudes and emotional experiences toward the subject have a great impact on the effectiveness of learning.

But conversely, if you make good use of this brain learning principle, anyone can learn and understand mathematics to a high level.

Using mindset and metacognitive theory

Make your child fearless of any problem.

Parents would like to believe that even if their children don't like it and can't do it now, if they keep asking them to do it, they will eventually do well.

However, the author says that it will not be very effective unless you change the child's attitude and feelings toward math, that is, their mindset.

According to mindset theory, when you believe you can learn something and take on a challenge with effort, you will learn more in the same amount of time than if you don't believe in yourself or the importance of the challenge.

This book presents amazing strategies that will fundamentally change the way students approach mathematics.

Every time I start a lecture, I tell people that our brains are always growing, connecting, and strengthening their pathways.

There is no such thing as a 'math brain', and our brains are constantly changing.

I want my students to try hard and make mistakes.

Because the time we spend working is the really important time when our brains form, connect, and strengthen pathways.

(Page 104)

It is also important to utilize metacognition.

The author demonstrates through several teaching examples that having children reflect on their learning by keeping a math journal rather than having them solve math worksheets, sharing stories related to numbers in their daily lives with their children, and providing comments expressing future expectations rather than current scores are more effective ways to help children learn math.

In fact, students don't know which method is best.

Moreover, most students learn unproductive approaches because they are exposed to a harsh grading culture and a narrow definition of mathematics.

The important thing is that learning a metacognitive learning approach that teaches students to be open-minded and curious about a variety of mathematical ideas changes all of this.

(Page 83)

When the process of trying, failing, and trying again is accepted comfortably and without feeling bad, children will not shrink from difficult problems but will gladly jump into them.

This book shatters long-held stereotypes about math studies and provides powerful tools to help children develop into math experts and, more importantly, fearless explorers of the world of mathematics.

The Secrets of Learning and Growth: A Cross-Cultural Approach to Neuroscience, Psychology, and Education

As the number of parents hoping their children will pursue medical studies increases, the craze for 'early math education' is heating up.

In Daechi-dong, it is common for children to start learning 'Daksu' (short for 'Dakchigo Math') from the age of 4.

Given this situation, the word 'supoja' (short for 'math giver'), which was used among middle and high school students in the past, has come down to elementary school.

According to a survey, one in eight elementary school students consider themselves to be a "student dropout."

But honestly, adults know better why kids hate math.

Because I experienced it firsthand.

The blackboard is filled with numbers and symbols whose meanings are unknown.

After the one-sided problem-solving lecture, you now have to quickly solve the problem within the time limit and get the correct answer.

The score doesn't reflect any of my effort or interest.

How many people can possibly enjoy math like this? Ultimately, for most, math class remains a "terrible" experience.

Does math have to be taught this way? Are there better methods? Parents who harbor these doubts will be amazed by the new math study method introduced in "How Math Brains Are Developed."

The author, Stanford University professor Joe Boller, has been researching learning conditions that can unleash mathematical potential for the past 30 years, working across neuroscience, psychology, and education.

And we share with teachers and parents around the world learning methods and examples that have been successful in improving the math achievement of students of all ages, levels, and races.

Neither the child nor the math is at fault.

The problem is the wrong study method.

Many people think that math is something you are born with.

Representative examples include statements like, ‘I’m not good at math’ or ‘I’m not suited for math.’

But neuroscience research shows that our brains are not fixed, but are constantly changing and growing.

In other words, we find math difficult and difficult to understand because we are not studying in a way that allows our brains to learn effectively.

Let's think back to the division of fractions we learned in elementary school.

Teachers constantly drill students into the "flip and multiply" method, but rarely explain why they should do it.

Children who learn and memorize only the rules that produce answers quickly and accurately are bound to get lost in the ever-growing list of formulas as they progress.

When young children first learn addition, it takes up a lot of space in their brains.

This knowledge becomes compressed over the years, taking up less and less physical space in the brain.

So when you're asked to do 3+4 as an adult, you can quickly and easily retrieve that knowledge in a compressed, small space.

This compression creates more and more learning space in our brains.

But Gray and Toll, in their landmark paper, argue that we can only compress concepts.

If children only learn the rules and methods, compression will not occur at all.

(Page 230)

The practice of constantly testing children to see if they have learned properly can also have a negative impact on learning.

This makes children believe that the essence of math is getting the right answer.

As a result, children who have experienced repeated failures in assessments and tests naturally conclude that they do not have mathematical talent or aptitude and give up.

Scientists have found that when people with math anxiety are presented with math problems, their fear centers in the brain activate, much like when they see snakes or spiders.

Fear and anxiety disable parts of the brain, including the hippocampus, which impairs learning ability.

On the other hand, there is a considerable amount of research showing that positive thoughts and beliefs about math activate these important parts of the brain, which improves learning ability and achievement.

(Page 33)

Our brain is not a computer that outputs what it inputs.

Knowledge that is not actively reconstructed in the mind is prone to evaporation, and learning attitudes and emotional experiences toward the subject have a great impact on the effectiveness of learning.

But conversely, if you make good use of this brain learning principle, anyone can learn and understand mathematics to a high level.

Using mindset and metacognitive theory

Make your child fearless of any problem.

Parents would like to believe that even if their children don't like it and can't do it now, if they keep asking them to do it, they will eventually do well.

However, the author says that it will not be very effective unless you change the child's attitude and feelings toward math, that is, their mindset.

According to mindset theory, when you believe you can learn something and take on a challenge with effort, you will learn more in the same amount of time than if you don't believe in yourself or the importance of the challenge.

This book presents amazing strategies that will fundamentally change the way students approach mathematics.

Every time I start a lecture, I tell people that our brains are always growing, connecting, and strengthening their pathways.

There is no such thing as a 'math brain', and our brains are constantly changing.

I want my students to try hard and make mistakes.

Because the time we spend working is the really important time when our brains form, connect, and strengthen pathways.

(Page 104)

It is also important to utilize metacognition.

The author demonstrates through several teaching examples that having children reflect on their learning by keeping a math journal rather than having them solve math worksheets, sharing stories related to numbers in their daily lives with their children, and providing comments expressing future expectations rather than current scores are more effective ways to help children learn math.

In fact, students don't know which method is best.

Moreover, most students learn unproductive approaches because they are exposed to a harsh grading culture and a narrow definition of mathematics.

The important thing is that learning a metacognitive learning approach that teaches students to be open-minded and curious about a variety of mathematical ideas changes all of this.

(Page 83)

When the process of trying, failing, and trying again is accepted comfortably and without feeling bad, children will not shrink from difficult problems but will gladly jump into them.

This book shatters long-held stereotypes about math studies and provides powerful tools to help children develop into math experts and, more importantly, fearless explorers of the world of mathematics.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: October 21, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 368 pages | 630g | 150*215*25mm

- ISBN13: 9788901289564

- ISBN10: 8901289563

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)