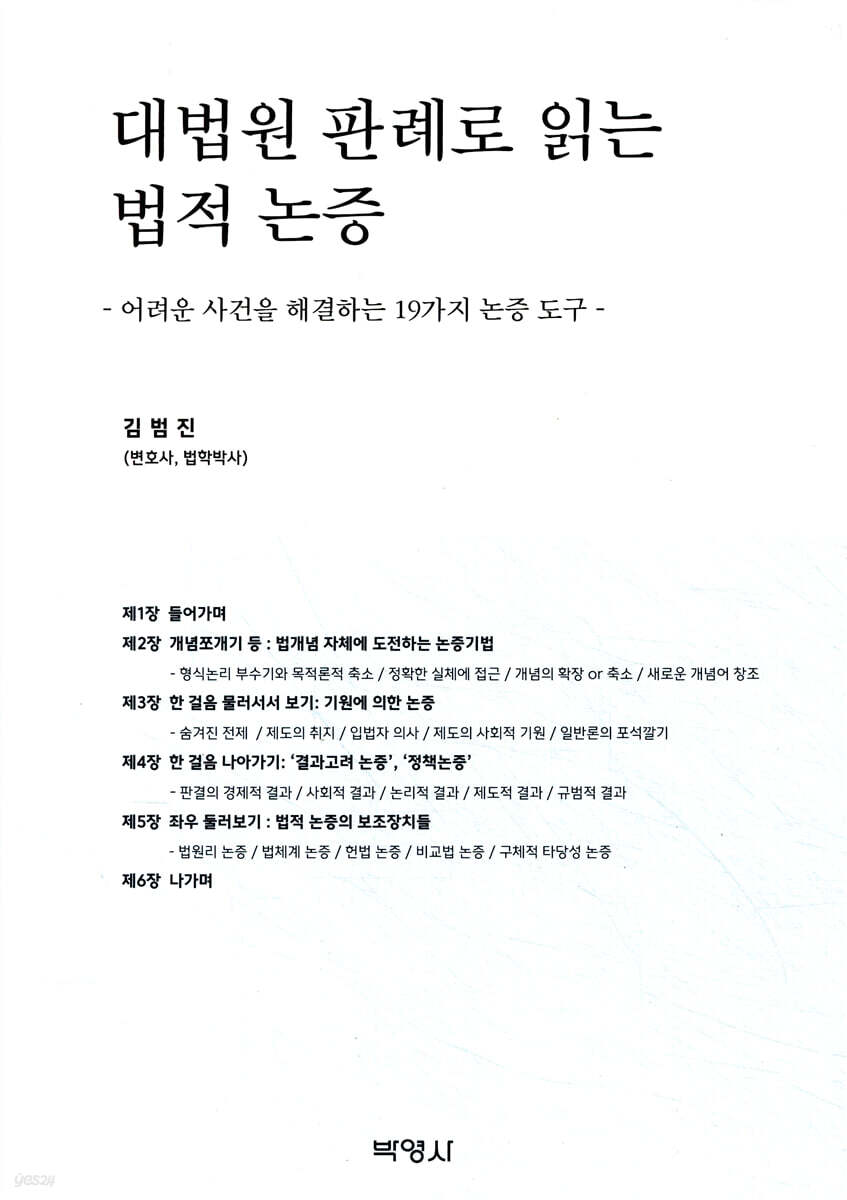

Legal Arguments Based on Supreme Court Case Law

|

Description

index

Chapter 1 Introduction

1.

Argument, Legal Argument, Difficult Case 3

(1) Meaning of argument 3

(2) Difficult Cases and Arguments 4

2.

Limitations and Cautions of This Book 6

Chapter 2: Splitting Concepts, etc.: Argumentative Techniques that Challenge the Concept of Law Itself

Section 1 Introduction 11

1.

Introduction 11

2.

What is concept splitting? 11

3.

13 Reasons Why Splitting Concepts Is a Problem in Legal Argument

Section 2: Review by Type 15

Ⅰ.

Type 1: Conceptual Splitting, Formal Logic Breakdown, and Teleological Reduction 15

1.

Entering 15

(1) Overcoming fallacies in arguments using formal logic 15

(2) Legal theory aspect: teleological reduction 16

2.

Specific examples 17

3.

25 Things to Consider and Summarize

Ⅱ.

Type 2: Splitting concepts and capturing precise entities 26

1.

Entering 26

2.

Specific examples 27

3.

Conclusion: 38 Further Thoughts

Ⅲ.

Type 3: Changing the Scope of Concepts—Expansion vs. Reduction of Concepts 39

1.

Entering 39

(1) Meaning 39

(2) Legal Theory Review 39

2.

40 specific examples

(1) Expansion of the scope of inclusion 40

(2) Reduction of the scope of inclusion 46

3.

Finish 50

Ⅳ.

Type 4: Creating New Concepts and Reusing Existing Concepts 51

1.

Enter 51

(1) Meaning 51

(2) Legal Theory Review 51

2.

Specific examples 53

(1) Use of concept words to complement existing concepts 53

(2) Some examples of utilizing existing concepts 57

3.

Conclusion, Further Thoughts 59

Section 3: Going Out 60

Chapter 3: One Step Backwards: The Argument from Origins

Section 1 Introduction 63

Section 2: Review by Type 64

Ⅰ.

Type 1: Finding Hidden Assumptions 64

1.

Enter 64

(1) Meaning 64

(2) Legal Argument and Hidden Premises 64

2.

Specific examples 67

3.

Final 78

Ⅱ.

Type 2: Argument from the Purpose of Legislation 79

1.

Entering 79

(1) Meaning 79

(2) Legal Theory Review 79

2.

Specific examples, subtypes 81

3.

Conclusion: 90 Points of Argument Based on the Intention of the System

(1) The most practical argumentation method 90

(2) Reject formal thinking and explore practical meaning 91

Ⅲ.

Type 3: Confirming the Legislator's Intention 92

1.

Entering 92

(1) Meaning 92

(2) Legal Theory Review 92

2.

Specific examples 94

3.

Finish 99

(1) Value as an argument for confirming legislative history 99

(2) Site information for checking legislative data 99

Ⅳ.

Type 4: Arguments about the social institutions that serve as the background for legal concepts 101

1.

Entering 101

(1) Meaning 101

(2) Legal theory review, scope of consideration of this section 101

2.

Specific examples 103

3.

Conclusion: Point 113 of the Social Institutions Term Argument

V.

Type 5: General Premises and Preliminary Arguments 115

1.

Entering 115

(1) Meaning 115

(2) Legal Theory Review 116

2.

Specific examples 117

3.

Final 126

Section 3: Going Out 127

Chapter 4: One Step Forward: "Consequences-Based Argument" and "Policy Argument"

Section 1 Introduction 131

1.

Meaning 131

2.

Legal Theory Debate: Negative Views and Counterarguments to Policy Arguments and Consequence-Considering Arguments 132

Section 2 Review of Detailed Types 137

Ⅰ.

Type 1: Economic Consequences of Judgments—Transaction Costs, Utility Maximization, Law & Economics 137

1.

Entering 137

(1) Meaning 137

(2) Legal Theory Review 137

2.

Specific examples 138

(1) The problem of direct cost burden 138

(2) Transaction Cost Problem 144

3.

Conclusion, Further Thoughts 151

(1) Theoretical background and diverse spectrum of problems 151

(2) Problem of secondary results 152

Ⅱ.

Type 2: Social Consequences of Judgments—Collateral Spillover Effects, 'Slippery Slope', 'Camel's Nose' 153

1.

Entering 153

(1) Meaning 153

(2) Legal Theory Review 153

2.

Specific examples 154

3.

Final 162

Ⅲ.

Type 3: Logical Consequences of a Judgment—Arguments to Avoid Absurd Results, the “Absurd Result Rule” 163

1.

Entering 163

(1) Meaning 163

(2) Legal Theory Review 164

2.

Specific examples 164

3.

Conclusion, Further Thoughts 179

(1) Problems from the perspective of argument theory 179

(2) Characteristics of this type 179

(3) Thinking game about the number of cases 180

Ⅳ.

Type 4: Institutional Consequences of Judgments—Arguments from the Incompleteness of Nearby Institutions 181

1.

Entering 181

(1) Meaning 181

(2) Legal Theory Review 181

2.

Specific examples 182

3.

Final 191

V.

Type 5: Normative Consequences of Judgment—Normatively Desirable Outcomes, Rules of Conduct for the Offender 192

1.

Entering 192

(1) Meaning 192

(2) Legal Theory Review 192

2.

Specific examples 193

3.

Final 199

Section 3 Conclusion 200

(1) Theoretical issues related to the argument from the standpoint of consequences 200

(2) Point 201 related to the argument considering the results

Chapter 5: Looking Left and Right: Auxiliary Devices of Legal Argument

Section 1 Introduction 205

Section 2 Review of Detailed Types 207

Ⅰ.

Type 1: Argument from Principle—Legal Principles and Legal Arguments 207

1.

Entering 207

(1) Meaning 207

(2) Legal Theory Issues: The Function and Limitations of Legal Principles in Legal Arguments 208

(3) Types of legal principles explicitly cited in Supreme Court precedents 210

(4) The complex interaction between legal principles and positive law 211

2.

Review 212 by Type

(1) Detailed Type 1: Cases where the wording of the law, existing legal principles, and court principles are in direct conflict 212

(2) Subtype 2: Coexistence of Legal Principles and Legal Judgments Type 216

(3) Detailed Type 3: Mixed Doubles Game Method - Type 222 in which there is a conflict between legal principles on the surface and a conflict between legal principles behind the scenes.

3.

Conclusion: Principle Argument Point 229

(1) Priority should be given to concrete legal principles over abstract legal principles 229

(2) Elimination of abstractness through combination with other arguments, including the argument considering the consequences 230

Ⅱ.

Type 2: Systematic Argument—Unity of Legal Systems and Legal Argument 231

1.

Entering 231

(1) Meaning 231

(2) Legal Theory Review 231

2.

Detailed Type Review 232

(1) Type 1: Relationships with immediate neighbors 232

(2) Type 2: Consideration of the overall system of a single law 234

(3) Type 3: Review of other laws governing similar matters 236

(4) Type 4: Systematic consistency between case laws 239

(5) Others: Various types of mixing and supplementing defects in the law 242

3.

Final 243

Ⅲ.

Type 3: Constitutional Argument: Judicial Interpretation and Application and the Constitution 245

1.

Enter 245

(1) Meaning 245

(2) Recent legal theory discussions 245

(3) Trends in Constitutional Argument in Practice 246

2.

Specific examples 247

3.

Conclusion: Characteristics of Constitutional Argument, Point 254

(1) Relevance to other arguments 254

(2) Constitutional Court Decision, Legislative Purpose, and Legislative History 254

Ⅳ.

Type 4: Comparative Law Argumentation—International Trends and Legal Argumentation 255

1.

Enter 255

(1) Meaning 255

(2) Legal Theory Review 255

2.

Specific examples 256

3.

Final 263

V.

Type 5: Concrete Validity Argument: General Abstractness vs. Individuality 264

1.

Enter 264

(1) Meaning 264

(2) Legal Theory Review 264

2.

266 reviews by type

3.

Final 274

(1) General abstraction and comprehensive consideration theory 274

(2) Specific validity as an argumentation tool 275

Section 3 Conclusion 276

Chapter 6: Exit 279

Reference 283

1.

Argument, Legal Argument, Difficult Case 3

(1) Meaning of argument 3

(2) Difficult Cases and Arguments 4

2.

Limitations and Cautions of This Book 6

Chapter 2: Splitting Concepts, etc.: Argumentative Techniques that Challenge the Concept of Law Itself

Section 1 Introduction 11

1.

Introduction 11

2.

What is concept splitting? 11

3.

13 Reasons Why Splitting Concepts Is a Problem in Legal Argument

Section 2: Review by Type 15

Ⅰ.

Type 1: Conceptual Splitting, Formal Logic Breakdown, and Teleological Reduction 15

1.

Entering 15

(1) Overcoming fallacies in arguments using formal logic 15

(2) Legal theory aspect: teleological reduction 16

2.

Specific examples 17

3.

25 Things to Consider and Summarize

Ⅱ.

Type 2: Splitting concepts and capturing precise entities 26

1.

Entering 26

2.

Specific examples 27

3.

Conclusion: 38 Further Thoughts

Ⅲ.

Type 3: Changing the Scope of Concepts—Expansion vs. Reduction of Concepts 39

1.

Entering 39

(1) Meaning 39

(2) Legal Theory Review 39

2.

40 specific examples

(1) Expansion of the scope of inclusion 40

(2) Reduction of the scope of inclusion 46

3.

Finish 50

Ⅳ.

Type 4: Creating New Concepts and Reusing Existing Concepts 51

1.

Enter 51

(1) Meaning 51

(2) Legal Theory Review 51

2.

Specific examples 53

(1) Use of concept words to complement existing concepts 53

(2) Some examples of utilizing existing concepts 57

3.

Conclusion, Further Thoughts 59

Section 3: Going Out 60

Chapter 3: One Step Backwards: The Argument from Origins

Section 1 Introduction 63

Section 2: Review by Type 64

Ⅰ.

Type 1: Finding Hidden Assumptions 64

1.

Enter 64

(1) Meaning 64

(2) Legal Argument and Hidden Premises 64

2.

Specific examples 67

3.

Final 78

Ⅱ.

Type 2: Argument from the Purpose of Legislation 79

1.

Entering 79

(1) Meaning 79

(2) Legal Theory Review 79

2.

Specific examples, subtypes 81

3.

Conclusion: 90 Points of Argument Based on the Intention of the System

(1) The most practical argumentation method 90

(2) Reject formal thinking and explore practical meaning 91

Ⅲ.

Type 3: Confirming the Legislator's Intention 92

1.

Entering 92

(1) Meaning 92

(2) Legal Theory Review 92

2.

Specific examples 94

3.

Finish 99

(1) Value as an argument for confirming legislative history 99

(2) Site information for checking legislative data 99

Ⅳ.

Type 4: Arguments about the social institutions that serve as the background for legal concepts 101

1.

Entering 101

(1) Meaning 101

(2) Legal theory review, scope of consideration of this section 101

2.

Specific examples 103

3.

Conclusion: Point 113 of the Social Institutions Term Argument

V.

Type 5: General Premises and Preliminary Arguments 115

1.

Entering 115

(1) Meaning 115

(2) Legal Theory Review 116

2.

Specific examples 117

3.

Final 126

Section 3: Going Out 127

Chapter 4: One Step Forward: "Consequences-Based Argument" and "Policy Argument"

Section 1 Introduction 131

1.

Meaning 131

2.

Legal Theory Debate: Negative Views and Counterarguments to Policy Arguments and Consequence-Considering Arguments 132

Section 2 Review of Detailed Types 137

Ⅰ.

Type 1: Economic Consequences of Judgments—Transaction Costs, Utility Maximization, Law & Economics 137

1.

Entering 137

(1) Meaning 137

(2) Legal Theory Review 137

2.

Specific examples 138

(1) The problem of direct cost burden 138

(2) Transaction Cost Problem 144

3.

Conclusion, Further Thoughts 151

(1) Theoretical background and diverse spectrum of problems 151

(2) Problem of secondary results 152

Ⅱ.

Type 2: Social Consequences of Judgments—Collateral Spillover Effects, 'Slippery Slope', 'Camel's Nose' 153

1.

Entering 153

(1) Meaning 153

(2) Legal Theory Review 153

2.

Specific examples 154

3.

Final 162

Ⅲ.

Type 3: Logical Consequences of a Judgment—Arguments to Avoid Absurd Results, the “Absurd Result Rule” 163

1.

Entering 163

(1) Meaning 163

(2) Legal Theory Review 164

2.

Specific examples 164

3.

Conclusion, Further Thoughts 179

(1) Problems from the perspective of argument theory 179

(2) Characteristics of this type 179

(3) Thinking game about the number of cases 180

Ⅳ.

Type 4: Institutional Consequences of Judgments—Arguments from the Incompleteness of Nearby Institutions 181

1.

Entering 181

(1) Meaning 181

(2) Legal Theory Review 181

2.

Specific examples 182

3.

Final 191

V.

Type 5: Normative Consequences of Judgment—Normatively Desirable Outcomes, Rules of Conduct for the Offender 192

1.

Entering 192

(1) Meaning 192

(2) Legal Theory Review 192

2.

Specific examples 193

3.

Final 199

Section 3 Conclusion 200

(1) Theoretical issues related to the argument from the standpoint of consequences 200

(2) Point 201 related to the argument considering the results

Chapter 5: Looking Left and Right: Auxiliary Devices of Legal Argument

Section 1 Introduction 205

Section 2 Review of Detailed Types 207

Ⅰ.

Type 1: Argument from Principle—Legal Principles and Legal Arguments 207

1.

Entering 207

(1) Meaning 207

(2) Legal Theory Issues: The Function and Limitations of Legal Principles in Legal Arguments 208

(3) Types of legal principles explicitly cited in Supreme Court precedents 210

(4) The complex interaction between legal principles and positive law 211

2.

Review 212 by Type

(1) Detailed Type 1: Cases where the wording of the law, existing legal principles, and court principles are in direct conflict 212

(2) Subtype 2: Coexistence of Legal Principles and Legal Judgments Type 216

(3) Detailed Type 3: Mixed Doubles Game Method - Type 222 in which there is a conflict between legal principles on the surface and a conflict between legal principles behind the scenes.

3.

Conclusion: Principle Argument Point 229

(1) Priority should be given to concrete legal principles over abstract legal principles 229

(2) Elimination of abstractness through combination with other arguments, including the argument considering the consequences 230

Ⅱ.

Type 2: Systematic Argument—Unity of Legal Systems and Legal Argument 231

1.

Entering 231

(1) Meaning 231

(2) Legal Theory Review 231

2.

Detailed Type Review 232

(1) Type 1: Relationships with immediate neighbors 232

(2) Type 2: Consideration of the overall system of a single law 234

(3) Type 3: Review of other laws governing similar matters 236

(4) Type 4: Systematic consistency between case laws 239

(5) Others: Various types of mixing and supplementing defects in the law 242

3.

Final 243

Ⅲ.

Type 3: Constitutional Argument: Judicial Interpretation and Application and the Constitution 245

1.

Enter 245

(1) Meaning 245

(2) Recent legal theory discussions 245

(3) Trends in Constitutional Argument in Practice 246

2.

Specific examples 247

3.

Conclusion: Characteristics of Constitutional Argument, Point 254

(1) Relevance to other arguments 254

(2) Constitutional Court Decision, Legislative Purpose, and Legislative History 254

Ⅳ.

Type 4: Comparative Law Argumentation—International Trends and Legal Argumentation 255

1.

Enter 255

(1) Meaning 255

(2) Legal Theory Review 255

2.

Specific examples 256

3.

Final 263

V.

Type 5: Concrete Validity Argument: General Abstractness vs. Individuality 264

1.

Enter 264

(1) Meaning 264

(2) Legal Theory Review 264

2.

266 reviews by type

3.

Final 274

(1) General abstraction and comprehensive consideration theory 274

(2) Specific validity as an argumentation tool 275

Section 3 Conclusion 276

Chapter 6: Exit 279

Reference 283

Publisher's Review

introduction

Several years ago, feeling overwhelmed by work and depleted of knowledge of law and precedents, I began reading Supreme Court en banc decisions on the subway to and from work.

As I read through the controversial decisions of the Supreme Court en banc one by one, I suddenly felt that, although the content varied from case to case, something similar was being repeated endlessly in the logical structure.

Although the topics covered by controversial Supreme Court decisions vary from case to case, there is a common thread underlying the points of conflict between majority and dissenting opinions and the basic structure through which the debate unfolds.

And I thought it might be possible to organize such a repetitive logical structure.

As a litigation attorney, I have been interested in basic legal studies such as legal argument theory and legal methodology for some time.

By chance, I had the opportunity to participate in the Methodology Research Group, a basic law research group.

I was able to learn a lot by repeatedly attending seminars with professors with deep knowledge.

However, I also learned that there is a certain gap between the discourse system of scholars and the language code of practice.

This book analyzes and organizes legal arguments in practice from the perspective of a practitioner, focusing on Supreme Court precedents.

These attempts are not merely of theoretical interest.

From a practitioner's perspective, deciding what logic to construct and what arguments to present in a difficult case is the task itself.

Reading controversial Supreme Court decisions can serve as a foundation for good arguments.

In particular, the decision of the Supreme Court en banc is a condensed body of the thoughts and wisdom of the Supreme Court justices, through the parties, representatives, lower court judges, and judicial research officers of the first to third trials.

Naturally, it has to be condensed with good arguments and logic.

Reading such writings can be a source of thought for practitioners.

Since 2018, I have been teaching writing at law schools, cyber universities, etc.

In 2021, I published a book titled “Writing for Lawyers” based on the lecture notes I created.

The following year, I was asked by a law newspaper to contribute to a column called ‘Books I Wrote.’

In the article, the author explains his motivation for writing the book:

'Although law is a practical discipline, there is still a large gap between practice and theory.

As a result, there are many gaps in the theory that are needed in practice.

Writing is one of them, and the author wanted to bridge that gap, even if only a little.' This book is in the same vein.

What lawyers do every day is argument.

But there is no education in argumentation, whether theoretical or practical.

I just read textbooks and court decisions repeatedly and learn them intuitively.

I found the work of organizing these blank spaces so interesting and rewarding that I ended up publishing my second book.

Although I understand that this is a tentative and insufficient piece of writing, I hope that this work will provide practitioners with an opportunity to organize their thoughts and that it will provide scholars with an opportunity to convey the concerns of practitioners.

I would like to express my gratitude to Park Young-sa, who allowed me to publish this book; to the editorial director, Lee Seung-hyun, who neatly completed the meticulous editing; to the professors of the Methodology Research Association, who taught me much despite my shortcomings; to my senior and junior lawyers; and to my loving wife, son Su-han, and daughter Su-hyeon.

2025.

9. 10.

Several years ago, feeling overwhelmed by work and depleted of knowledge of law and precedents, I began reading Supreme Court en banc decisions on the subway to and from work.

As I read through the controversial decisions of the Supreme Court en banc one by one, I suddenly felt that, although the content varied from case to case, something similar was being repeated endlessly in the logical structure.

Although the topics covered by controversial Supreme Court decisions vary from case to case, there is a common thread underlying the points of conflict between majority and dissenting opinions and the basic structure through which the debate unfolds.

And I thought it might be possible to organize such a repetitive logical structure.

As a litigation attorney, I have been interested in basic legal studies such as legal argument theory and legal methodology for some time.

By chance, I had the opportunity to participate in the Methodology Research Group, a basic law research group.

I was able to learn a lot by repeatedly attending seminars with professors with deep knowledge.

However, I also learned that there is a certain gap between the discourse system of scholars and the language code of practice.

This book analyzes and organizes legal arguments in practice from the perspective of a practitioner, focusing on Supreme Court precedents.

These attempts are not merely of theoretical interest.

From a practitioner's perspective, deciding what logic to construct and what arguments to present in a difficult case is the task itself.

Reading controversial Supreme Court decisions can serve as a foundation for good arguments.

In particular, the decision of the Supreme Court en banc is a condensed body of the thoughts and wisdom of the Supreme Court justices, through the parties, representatives, lower court judges, and judicial research officers of the first to third trials.

Naturally, it has to be condensed with good arguments and logic.

Reading such writings can be a source of thought for practitioners.

Since 2018, I have been teaching writing at law schools, cyber universities, etc.

In 2021, I published a book titled “Writing for Lawyers” based on the lecture notes I created.

The following year, I was asked by a law newspaper to contribute to a column called ‘Books I Wrote.’

In the article, the author explains his motivation for writing the book:

'Although law is a practical discipline, there is still a large gap between practice and theory.

As a result, there are many gaps in the theory that are needed in practice.

Writing is one of them, and the author wanted to bridge that gap, even if only a little.' This book is in the same vein.

What lawyers do every day is argument.

But there is no education in argumentation, whether theoretical or practical.

I just read textbooks and court decisions repeatedly and learn them intuitively.

I found the work of organizing these blank spaces so interesting and rewarding that I ended up publishing my second book.

Although I understand that this is a tentative and insufficient piece of writing, I hope that this work will provide practitioners with an opportunity to organize their thoughts and that it will provide scholars with an opportunity to convey the concerns of practitioners.

I would like to express my gratitude to Park Young-sa, who allowed me to publish this book; to the editorial director, Lee Seung-hyun, who neatly completed the meticulous editing; to the professors of the Methodology Research Association, who taught me much despite my shortcomings; to my senior and junior lawyers; and to my loving wife, son Su-han, and daughter Su-hyeon.

2025.

9. 10.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: September 25, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 296 pages | 171*244*20mm

- ISBN13: 9791130324395

- ISBN10: 1130324397

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)