Split me and take me out

|

Description

Book Introduction

“Is it a sin to want to know more about the world?”

A textual adventure that crosses boundaries and risks one's life for the truth.

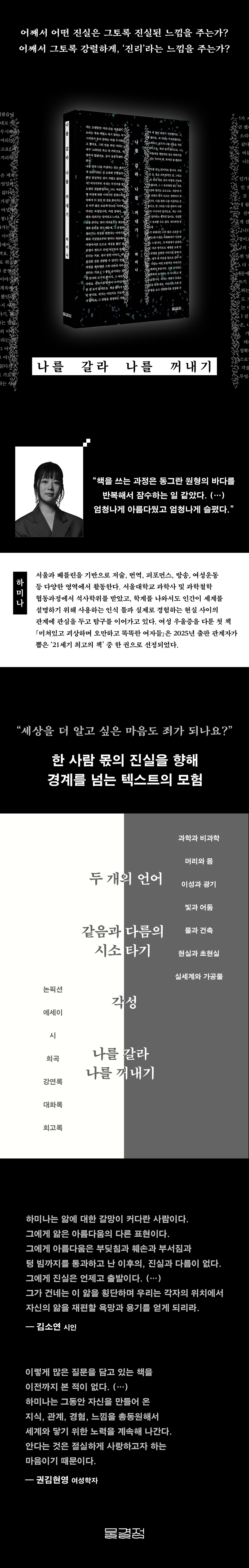

Hamina's new work, "Cut Me Apart and Take Me Out," has been published as the first book by the East Asian literature and art brand Mulgajeom.

"Cut Me Apart and Take Me Out" is a hybrid text that weaves together the author's writings from January 2021 to October 2025, bringing them together, colliding them, and intertwining them.

This book, which crosses genres including nonfiction, essays, poetry, plays, lectures, dialogues, and memoirs, and themes such as science and pseudoscience, the head and the body, reason and madness, light and darkness, the real world and the artificial, aims to reach a place where a spectacular spectacle unfolds.

The landscape of truth that the author encountered in the darkness, overcoming the trap of knowledge and holding onto the fear of ignorance, was “incredibly beautiful and terribly sad.”

In "Cut Me Apart", a Nobel Prize winner in physics and a medieval witch, a great writer of world literature and women without language, Carl Sagan and Baridegi, the light of enlightenment and the light of revelation all appear together.

Before long conversations with artificial intelligence (AI), there is the murmur of a small seaside puddle, before harm and harm, there is a part of ourselves that cannot be separated, before the myth of motherhood, there is the unique world of the child.

They do not serve a single narrative, they simply exist there, competing.

As our experiences are, as are we ourselves, with multiple voices and multiple narratives.

So, some truths can only be encountered by entering another world that shines through the cracks of the existing world, by splitting myself apart and taking me out.

The me who was divided like that dies and the me who was taken out lives and changes the question.

From ‘What is a human being?’ to ‘What does a human being want to become?’

This is also the vision of our possibilities that the author presents with pure fascination and passionate commitment.

A textual adventure that crosses boundaries and risks one's life for the truth.

Hamina's new work, "Cut Me Apart and Take Me Out," has been published as the first book by the East Asian literature and art brand Mulgajeom.

"Cut Me Apart and Take Me Out" is a hybrid text that weaves together the author's writings from January 2021 to October 2025, bringing them together, colliding them, and intertwining them.

This book, which crosses genres including nonfiction, essays, poetry, plays, lectures, dialogues, and memoirs, and themes such as science and pseudoscience, the head and the body, reason and madness, light and darkness, the real world and the artificial, aims to reach a place where a spectacular spectacle unfolds.

The landscape of truth that the author encountered in the darkness, overcoming the trap of knowledge and holding onto the fear of ignorance, was “incredibly beautiful and terribly sad.”

In "Cut Me Apart", a Nobel Prize winner in physics and a medieval witch, a great writer of world literature and women without language, Carl Sagan and Baridegi, the light of enlightenment and the light of revelation all appear together.

Before long conversations with artificial intelligence (AI), there is the murmur of a small seaside puddle, before harm and harm, there is a part of ourselves that cannot be separated, before the myth of motherhood, there is the unique world of the child.

They do not serve a single narrative, they simply exist there, competing.

As our experiences are, as are we ourselves, with multiple voices and multiple narratives.

So, some truths can only be encountered by entering another world that shines through the cracks of the existing world, by splitting myself apart and taking me out.

The me who was divided like that dies and the me who was taken out lives and changes the question.

From ‘What is a human being?’ to ‘What does a human being want to become?’

This is also the vision of our possibilities that the author presents with pure fascination and passionate commitment.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Prologue

Part 1 Two Languages

Part 2: Seesaw Between Sameness and Differentness

Part 3 Awakening

Part 4 Split Me and Take Me Out

Epilogue

Recommendation

main

Search

Part 1 Two Languages

Part 2: Seesaw Between Sameness and Differentness

Part 3 Awakening

Part 4 Split Me and Take Me Out

Epilogue

Recommendation

main

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

What is truth? That's not my question.

This question causes endless debate.

Why do some truths feel so true? That's my question.

Why do some truths feel so strongly 'truth'?

Does it go beyond the cognitive level and make it actually visible and audible?

How does it transcend individual experience and become a collective experience?

How does that perception make us see the person before us as an enemy, a perpetrator, or a demon? How does it drive us to kill him for the sake of "justice" or "peace"?

--- p.56

Learning doesn't happen as expected.

Every step is a new challenge.

There is nothing we can do in the face of fear.

You just have to be afraid and move forward.

But fear makes us see things differently than we should.

I wonder what would have happened if the man who felt fear in the presence of hysterical women had listened to their stories instead of 'treating' them.

Feeling fear during the learning process means, in other words, feeling fear because you are learning something.

(…) I imagine.

What would the story be like if Ming from "The Rising Sun" made her own film about herself? How different would the film have been if the girl from "The Exorcist" had been able to hold the camera herself?

It's important to talk about how marginalized women have been, but it's also important to talk about how illusory male-centeredness is and how many men are struggling and slipping within it.

I hope men can experience the comfort and coziness that comes from losing control and power.

For that, the testimony of the parties is required.

Tell me how male homosociality is ruining you.

Has your brother's world allowed you to live your own life? Or has it prevented you from doing so? It's not shameful to say so.

--- p.236

That's why, when I write like water, I start from my body.

It starts with trusting the feelings your body gives you.

In this moment, examine whether you feel happy, angry, anxious, or insulted.

Check to see if your body feels stiff, tired, sweaty, or if your heart is beating fast.

The body and emotions become compasses for finding truth.

This is about trusting and following the direction of the truer self that lies dormant within the educated self, the socialized self, and thus restoring the connection with myself.

--- p.327

For some time now, I have begun to feel that writing that consists of a single narrative, a grand narrative, a linear narrative, is somewhat violent.

The smoother and more convincing the narrative, the more it silences other possible versions of reality.

One narrative, once considered successful and even ethical, can change its form with surprising speed, becoming a tyrant who oppresses other narratives.

This question causes endless debate.

Why do some truths feel so true? That's my question.

Why do some truths feel so strongly 'truth'?

Does it go beyond the cognitive level and make it actually visible and audible?

How does it transcend individual experience and become a collective experience?

How does that perception make us see the person before us as an enemy, a perpetrator, or a demon? How does it drive us to kill him for the sake of "justice" or "peace"?

--- p.56

Learning doesn't happen as expected.

Every step is a new challenge.

There is nothing we can do in the face of fear.

You just have to be afraid and move forward.

But fear makes us see things differently than we should.

I wonder what would have happened if the man who felt fear in the presence of hysterical women had listened to their stories instead of 'treating' them.

Feeling fear during the learning process means, in other words, feeling fear because you are learning something.

(…) I imagine.

What would the story be like if Ming from "The Rising Sun" made her own film about herself? How different would the film have been if the girl from "The Exorcist" had been able to hold the camera herself?

It's important to talk about how marginalized women have been, but it's also important to talk about how illusory male-centeredness is and how many men are struggling and slipping within it.

I hope men can experience the comfort and coziness that comes from losing control and power.

For that, the testimony of the parties is required.

Tell me how male homosociality is ruining you.

Has your brother's world allowed you to live your own life? Or has it prevented you from doing so? It's not shameful to say so.

--- p.236

That's why, when I write like water, I start from my body.

It starts with trusting the feelings your body gives you.

In this moment, examine whether you feel happy, angry, anxious, or insulted.

Check to see if your body feels stiff, tired, sweaty, or if your heart is beating fast.

The body and emotions become compasses for finding truth.

This is about trusting and following the direction of the truer self that lies dormant within the educated self, the socialized self, and thus restoring the connection with myself.

--- p.327

For some time now, I have begun to feel that writing that consists of a single narrative, a grand narrative, a linear narrative, is somewhat violent.

The smoother and more convincing the narrative, the more it silences other possible versions of reality.

One narrative, once considered successful and even ethical, can change its form with surprising speed, becoming a tyrant who oppresses other narratives.

--- p.354

Publisher's Review

Collapse of the city in the sky

―The Passage of Science and 'Two Languages'

The book begins with two scenes.

A seventeen-year-old girl who has just learned about space and is in awe of the “wonder of discovering the world.”

And 'I', who repeatedly witnesses "the city I loved collapsing" at the beach.

The collapse of this 'city in the sky', which is said to consist of a single system of knowledge, symbolically shows the moment when knowledge that was once admired and followed disintegrates as it deviates from real life.

The joy of a time when sense and learning were one turns to confusion, but the author uses the cracks as a hint to tear down the city, build another city, and fall in love once again.

That city may collapse someday, but there's nothing we can do about it.

This collapse and rebirth is a concise metaphor for what happens within us when we decide to continue to learn about the world as we live, and when we resolve to approach the truth as best we can.

『Cut Me Apart and Take Me Out』 was originally planned as a book that looked at the history of science from a feminist perspective.

The author's science columns, which she began writing in January 2021, serve as the foundation for her work. They highlight female scientists who have dedicated themselves to science in discriminatory and hostile environments, while also criticizing science that promotes misunderstanding, discrimination, and hatred against women. These writings, which envision a better science for all on a global scale, capture Hamina's overflowing curiosity and extensive knowledge as a researcher of the history of science, and have garnered the interest and support of many readers.

While continuing the series, he wrote his master's thesis on the formation of knowledge about measuring depression, and based on the material left out of it, he published his first book, "Crazy, Weird, Arrogant, and Smart Women."

The book was widely read not only in Korea but also around the world, giving suffering women their voice back, and it was well-received by the public and both within and outside the publishing world, and is still widely read today.

Meanwhile, important changes were taking place within the author before and after writing his first book.

“Originally, I was a science philosophy aspirant,” and “I loved this discipline and wanted to make it my life’s work, and I did everything I could to prepare for it.” However, as I continued my research, I began to realize that I could not continue learning in my own way in academia.

Graduate school was not a place for me to study, but rather a place where I had to prove myself repeatedly amidst constant gaslighting and shame.

(…) Perhaps the problem was that I worked as a feminist activist while attending graduate school, that I had to go through a long sexual assault trial against a former professor at the same school, and that I constantly told my story in a space where I had to erase myself.

(…) The philosophy of science is a rather conservative discipline, and it seems to explore the nature of science from a rather internal and linguistic perspective.

(…) I found it fun to solve these problems.

It was like Sudoku.

Solving a Sudoku puzzle gives you the joy of thinking and finding the answer.

The more I do it, the smarter I feel.

But Sudoku is just Sudoku, and has no influence on the world outside of Sudoku.

Only in Sudoku do I feel omnipotent.

After the Gangnam Station murder in 2016, I decided not to study anything like Sudoku anymore.

Knowledge and life could no longer be separated. (133-134)

The moment when another city is demolished.

Starting from there, 『Cutting Me Apart and Taking Me Out』 can be seen as a book that talks about 'knowledge' in a different way from the author's previous works, while at the same time supporting and embracing those works from the ground up.

After another collapse, when science, which had been the destination, becomes a passageway, the existing world that had seemed solid begins to crack, and the author begins to see it with different eyes.

Mainstream science, which is filled with male-centric narratives in the Western world, did not align with the knowledge he had gained through his own life experiences.

Science that emphasizes differences, science that takes women's place, science that erases women from history, science that ignores those who are left behind and does not care for nature that has been pushed out of its subjectivity, all seemed to him to be "barbaric."

Only when we remove the biases and drop the authority can we imagine a better science without abandoning science.

It was a science that no longer excluded women, a science that “slapped convention and intuition in the face,” a science that cared for the Earth and all living beings.

And above all, this demolition also became an opportunity to open up a new world.

The author, by coming into contact with nature and regaining the eyes of a child, foresees that the world can be understood not only through scientific knowledge but also through “knowledge that is considered unscientific.”

Not because we 'believe' it is true, but because it is a system of knowledge that is outside of the Western, white, male-centric worldview.

When natural disasters and other events beyond human understanding occur, the systems of knowledge that have replaced science to explain the world; the systems of knowledge created by indigenous peoples in those regions before the knowledge we learn in schools was Westernized and colonized; the systems of knowledge that have allowed them to care for the minds and bodies of their communities in their own, unique ways… I'm interested in these things. (55)

So this book came to have 'two languages'.

This is also the reason why 『Cut Me Apart and Take Me Out』, despite devoting more than half of its volume to the history of science and science criticism, could not stop at being just a science book.

Of course, for the author, who has long written the 'Introduction' based on the grammar of rigorous scientific research with clear reason, crossing the boundary between science and non-science was a frightening, almost deathly thing.

But to the head that says, “I don’t want to die,” the body says,

“No, you have to die.

But you have to die well.” The woman is reborn and learns from the woman who died first.

“Now you just have to speak two languages.” This is the mantra of those who have awakened first, to those of us who are too often afraid to listen to our bodies and open our eyes to the wonders of nature.

'Cut you apart and take you out', like I did.

The author whispers.

“Perhaps we get closer to the truth when we admire what we feel rather than when we talk about what we know.”

So, you could say that 『Cut Me Apart and Take Me Out』 is an adventure story that continues without an ending.

As long as we keep breaking down and rebuilding, learning never ends, and there are no fixed truths in this journey.

The only question is how and where to start and how to proceed towards it.

This adventure is both a step forward and a step back.

It is progress and recovery at the same time.

From the moment we are born, we learn and feel this world, flowing somewhere. There is a natural order that governs all things in the world before we were born, and a primal sense that has been preserved across generations.

How can we find our true selves and establish a genuine connection with the world on this winding journey? Or perhaps we could rephrase the question this way:

“Who were we, before they defined us?” The author, emerging from madness and death, answers the questions posed in the book with several changes in expression.

“It is not an escape from the normal to the abnormal, but a recovery of the senses that humanity has had for a long time” (345-346).

Writing that embraces the truth

Beginning with the story of the "Voyager Golden Record," an Earth-introducing record sent by humanity into outer space, the book takes us past volcanoes and the edge of the ocean, through a laboratory 1,100 meters underground and a theater stage, and encounters a possessed girl, a shaman, and a medieval saint.

“I’m not a feminist, but…” (female scientist), “I can’t help but swear” (producer Min Hee-jin), “Ah, that’s the native species” (teacher Park Kyung-ni), amidst such words, a baby Yakushima Japanese macaque climbs a tree and plays, and a colony of small jellyfish floats across the sea.

The book's plot, which at first glance appears to be a series of chapters, lacks a coherent narrative.

This also seems similar to the path the author has taken.

Aspiring scientist, history researcher, science journalist, and science writer.

From one day on, I became a writer who wrote a variety of articles regardless of genre.

Activist, performer, diver.

A Berlin resident who suddenly left Korea, a feminist who suddenly returned and appeared on TV… … .

But from a different perspective, nothing seems as consistent as this book or this author's actions.

He fell in love with the sad and beautiful truth contained in dark, twisted, and strange things, and he moved towards carrying out that love every time.

Even though he was confused and scared, he threw himself into the world, learned about it with all his heart, and survived as himself.

If this book seems to draw a complex network of relationships instead of a clear plot, and to writhe through multiple worlds instead of converging into a single narrative, it is likely because of the author's way of relating to the world and the world he sees.

Could this arrangement be seen as evidence of his acceptance of the world as alive, as something changeable? As long as violence and suffering exist somewhere in this world, the world must remain alive, changeable.

“Because it is an extreme love for those who will come after.”

So, rather than asking, 'What did you write? Who are you?', why not try rephrasing the question this time?

'Where are these writings going, what kind of person are you trying to become?'

Hamina, who writes, wants to be honest with herself first.

The process of his writing truthfully seems very similar to the process of acquiring knowledge.

There is an experience where “the more I try to write, the more I stray from the core” and “I feel like I need to convey some truth about that experience, but writing can’t handle it.”

Just as he leaned toward knowledge beyond science when scientific knowledge was incomplete and inadequate, this time too he relies on bodily reactions, feelings and emotions, images, dreams and hallucinations, and revelations.

A text written in that way cannot be proven to be a translation.

It just evokes a sense of utmost truth.

The author calls this feminine writing, watery writing, or body writing.

Body-writing is written from division and confusion rather than harmony and unity, from oblivion rather than memory, from selflessness rather than self.

If the header controls and writes, the body text does not.

There is no will to control.

If the header creates itself according to the blueprint and plan, the body writes while following the flow.

Body - Write it down quickly.

The body sometimes does not understand what is written.

Or you can write something you don't understand.

The selflessness of the body and mind comes from knowing something greater than oneself.

The body does not try to take control of the text.

I just look at it.

Body-writing lets experience pass through it.

Body-writing uses itself as a tool.

While the header requires authoritative evidence, the body text relies on its own feelings.

What body-writing utilizes in writing is not papers, articles, or columns, but rather bodily reactions, feelings and emotions, images, dreams and hallucinations, and revelations.

The body cannot prove its own righteousness.

This only evokes a sense of utter truth. (72-73)

“How else is it possible?”

―Awake, alive

In “Cut Me Apart and Take Me Out,” the word truth appears in countless variations and repetitions.

“The goal of science is to get as close to the truth as possible.” “To believe in and follow the direction that your truer self points to.” “To avoid uncomfortable truths.” “For example, two truths may compete with each other.” “Are all truths of equal value?”… … .

Why is truth so important? At some point, for the author, this question became a matter of power.

To write and to possess language means to be in a state where one can influence others, and sometimes even steal or destroy the lives of other beings.

As countless writers have taken parts of other people's lives and written them for themselves.

Just as Francis Bacon borrowed the perspective and grammar of the witch trials to argue that nature should be tortured and interrogated, this led later generations to view nature as “a mechanical being to be understood and conquered, not a living organism.”

The author is startled to see in his dream that he is unknowingly exerting such influence.

The sentences I poured out were beautiful and powerful.

Right, right.

People were very sympathetic.

Meanwhile, a friend who was staggering outside the bus collapsed.

I was so surprised while giving a speech that I got off the bus and came to his rescue.

Then people praised my actions even more.

They applauded him, saying that he was an ethical person who saved even trashy people.

Before I knew it, I started thinking of myself that way too.

While people were applauding, I suddenly woke up in horror, horrified by what I was doing as a character in a dream and as a narrator. (58)

The reason Hamina's intelligence in "Cut Me Off and Take Me Out" is so special is because her attitude toward and exercise of knowledge is so awakened.

He knows how to speak with reason in the midst of reality, like any intellectual, that truth should be measured by context and coordinates, not history and authority.

But what is surprising is that at the same time, he descends within himself and takes that knowledge and puts it into practice in his dreams.

Conscious of the complexity of truth and wary of the ripple effects of power and authority, he eventually ends up splitting himself apart and taking himself out, even in his dreams.

And then he tells us what happened in the language of dreams.

Waking from his dream, he knows how to be free by choosing to be vulnerable and humble.

It is possible to approach some truth in that way.

When the author was stuck on writing, he asked himself:

“If I could let go of the desire to prove my point right” and “let go of the desire to be remembered or known,” could I go further? Could we ask ourselves these questions as we seek to connect with others and the world?

As Leslie Jamison puts it, “Looking, looking, not looking away as soon as you get what you need.

(…) just watching them become more and more complex and subvert the narratives we have written for them.” (Leslie Jamieson, translated by Song Seom-byeol, Make Them Scream, Make Them Burn, Banbi, 2023, p. 206) According to poet Kim Hye-soon, whining, dying, inventing.

To put it in Ellen Cixous’s terms, “the activity of a being that does not return to itself (…) becoming a woman and at the same time one who cares and advances within the world” (Ellen Cixous, translated by Eun-ju Hwang, 『The Time of Respector』, Eulyoo Publishing, 2025, p. 133).

Could this be the answer to the question, “What do humans want to become?”

Can we each take our truths into a world of greater possibility?

―The Passage of Science and 'Two Languages'

The book begins with two scenes.

A seventeen-year-old girl who has just learned about space and is in awe of the “wonder of discovering the world.”

And 'I', who repeatedly witnesses "the city I loved collapsing" at the beach.

The collapse of this 'city in the sky', which is said to consist of a single system of knowledge, symbolically shows the moment when knowledge that was once admired and followed disintegrates as it deviates from real life.

The joy of a time when sense and learning were one turns to confusion, but the author uses the cracks as a hint to tear down the city, build another city, and fall in love once again.

That city may collapse someday, but there's nothing we can do about it.

This collapse and rebirth is a concise metaphor for what happens within us when we decide to continue to learn about the world as we live, and when we resolve to approach the truth as best we can.

『Cut Me Apart and Take Me Out』 was originally planned as a book that looked at the history of science from a feminist perspective.

The author's science columns, which she began writing in January 2021, serve as the foundation for her work. They highlight female scientists who have dedicated themselves to science in discriminatory and hostile environments, while also criticizing science that promotes misunderstanding, discrimination, and hatred against women. These writings, which envision a better science for all on a global scale, capture Hamina's overflowing curiosity and extensive knowledge as a researcher of the history of science, and have garnered the interest and support of many readers.

While continuing the series, he wrote his master's thesis on the formation of knowledge about measuring depression, and based on the material left out of it, he published his first book, "Crazy, Weird, Arrogant, and Smart Women."

The book was widely read not only in Korea but also around the world, giving suffering women their voice back, and it was well-received by the public and both within and outside the publishing world, and is still widely read today.

Meanwhile, important changes were taking place within the author before and after writing his first book.

“Originally, I was a science philosophy aspirant,” and “I loved this discipline and wanted to make it my life’s work, and I did everything I could to prepare for it.” However, as I continued my research, I began to realize that I could not continue learning in my own way in academia.

Graduate school was not a place for me to study, but rather a place where I had to prove myself repeatedly amidst constant gaslighting and shame.

(…) Perhaps the problem was that I worked as a feminist activist while attending graduate school, that I had to go through a long sexual assault trial against a former professor at the same school, and that I constantly told my story in a space where I had to erase myself.

(…) The philosophy of science is a rather conservative discipline, and it seems to explore the nature of science from a rather internal and linguistic perspective.

(…) I found it fun to solve these problems.

It was like Sudoku.

Solving a Sudoku puzzle gives you the joy of thinking and finding the answer.

The more I do it, the smarter I feel.

But Sudoku is just Sudoku, and has no influence on the world outside of Sudoku.

Only in Sudoku do I feel omnipotent.

After the Gangnam Station murder in 2016, I decided not to study anything like Sudoku anymore.

Knowledge and life could no longer be separated. (133-134)

The moment when another city is demolished.

Starting from there, 『Cutting Me Apart and Taking Me Out』 can be seen as a book that talks about 'knowledge' in a different way from the author's previous works, while at the same time supporting and embracing those works from the ground up.

After another collapse, when science, which had been the destination, becomes a passageway, the existing world that had seemed solid begins to crack, and the author begins to see it with different eyes.

Mainstream science, which is filled with male-centric narratives in the Western world, did not align with the knowledge he had gained through his own life experiences.

Science that emphasizes differences, science that takes women's place, science that erases women from history, science that ignores those who are left behind and does not care for nature that has been pushed out of its subjectivity, all seemed to him to be "barbaric."

Only when we remove the biases and drop the authority can we imagine a better science without abandoning science.

It was a science that no longer excluded women, a science that “slapped convention and intuition in the face,” a science that cared for the Earth and all living beings.

And above all, this demolition also became an opportunity to open up a new world.

The author, by coming into contact with nature and regaining the eyes of a child, foresees that the world can be understood not only through scientific knowledge but also through “knowledge that is considered unscientific.”

Not because we 'believe' it is true, but because it is a system of knowledge that is outside of the Western, white, male-centric worldview.

When natural disasters and other events beyond human understanding occur, the systems of knowledge that have replaced science to explain the world; the systems of knowledge created by indigenous peoples in those regions before the knowledge we learn in schools was Westernized and colonized; the systems of knowledge that have allowed them to care for the minds and bodies of their communities in their own, unique ways… I'm interested in these things. (55)

So this book came to have 'two languages'.

This is also the reason why 『Cut Me Apart and Take Me Out』, despite devoting more than half of its volume to the history of science and science criticism, could not stop at being just a science book.

Of course, for the author, who has long written the 'Introduction' based on the grammar of rigorous scientific research with clear reason, crossing the boundary between science and non-science was a frightening, almost deathly thing.

But to the head that says, “I don’t want to die,” the body says,

“No, you have to die.

But you have to die well.” The woman is reborn and learns from the woman who died first.

“Now you just have to speak two languages.” This is the mantra of those who have awakened first, to those of us who are too often afraid to listen to our bodies and open our eyes to the wonders of nature.

'Cut you apart and take you out', like I did.

The author whispers.

“Perhaps we get closer to the truth when we admire what we feel rather than when we talk about what we know.”

So, you could say that 『Cut Me Apart and Take Me Out』 is an adventure story that continues without an ending.

As long as we keep breaking down and rebuilding, learning never ends, and there are no fixed truths in this journey.

The only question is how and where to start and how to proceed towards it.

This adventure is both a step forward and a step back.

It is progress and recovery at the same time.

From the moment we are born, we learn and feel this world, flowing somewhere. There is a natural order that governs all things in the world before we were born, and a primal sense that has been preserved across generations.

How can we find our true selves and establish a genuine connection with the world on this winding journey? Or perhaps we could rephrase the question this way:

“Who were we, before they defined us?” The author, emerging from madness and death, answers the questions posed in the book with several changes in expression.

“It is not an escape from the normal to the abnormal, but a recovery of the senses that humanity has had for a long time” (345-346).

Writing that embraces the truth

Beginning with the story of the "Voyager Golden Record," an Earth-introducing record sent by humanity into outer space, the book takes us past volcanoes and the edge of the ocean, through a laboratory 1,100 meters underground and a theater stage, and encounters a possessed girl, a shaman, and a medieval saint.

“I’m not a feminist, but…” (female scientist), “I can’t help but swear” (producer Min Hee-jin), “Ah, that’s the native species” (teacher Park Kyung-ni), amidst such words, a baby Yakushima Japanese macaque climbs a tree and plays, and a colony of small jellyfish floats across the sea.

The book's plot, which at first glance appears to be a series of chapters, lacks a coherent narrative.

This also seems similar to the path the author has taken.

Aspiring scientist, history researcher, science journalist, and science writer.

From one day on, I became a writer who wrote a variety of articles regardless of genre.

Activist, performer, diver.

A Berlin resident who suddenly left Korea, a feminist who suddenly returned and appeared on TV… … .

But from a different perspective, nothing seems as consistent as this book or this author's actions.

He fell in love with the sad and beautiful truth contained in dark, twisted, and strange things, and he moved towards carrying out that love every time.

Even though he was confused and scared, he threw himself into the world, learned about it with all his heart, and survived as himself.

If this book seems to draw a complex network of relationships instead of a clear plot, and to writhe through multiple worlds instead of converging into a single narrative, it is likely because of the author's way of relating to the world and the world he sees.

Could this arrangement be seen as evidence of his acceptance of the world as alive, as something changeable? As long as violence and suffering exist somewhere in this world, the world must remain alive, changeable.

“Because it is an extreme love for those who will come after.”

So, rather than asking, 'What did you write? Who are you?', why not try rephrasing the question this time?

'Where are these writings going, what kind of person are you trying to become?'

Hamina, who writes, wants to be honest with herself first.

The process of his writing truthfully seems very similar to the process of acquiring knowledge.

There is an experience where “the more I try to write, the more I stray from the core” and “I feel like I need to convey some truth about that experience, but writing can’t handle it.”

Just as he leaned toward knowledge beyond science when scientific knowledge was incomplete and inadequate, this time too he relies on bodily reactions, feelings and emotions, images, dreams and hallucinations, and revelations.

A text written in that way cannot be proven to be a translation.

It just evokes a sense of utmost truth.

The author calls this feminine writing, watery writing, or body writing.

Body-writing is written from division and confusion rather than harmony and unity, from oblivion rather than memory, from selflessness rather than self.

If the header controls and writes, the body text does not.

There is no will to control.

If the header creates itself according to the blueprint and plan, the body writes while following the flow.

Body - Write it down quickly.

The body sometimes does not understand what is written.

Or you can write something you don't understand.

The selflessness of the body and mind comes from knowing something greater than oneself.

The body does not try to take control of the text.

I just look at it.

Body-writing lets experience pass through it.

Body-writing uses itself as a tool.

While the header requires authoritative evidence, the body text relies on its own feelings.

What body-writing utilizes in writing is not papers, articles, or columns, but rather bodily reactions, feelings and emotions, images, dreams and hallucinations, and revelations.

The body cannot prove its own righteousness.

This only evokes a sense of utter truth. (72-73)

“How else is it possible?”

―Awake, alive

In “Cut Me Apart and Take Me Out,” the word truth appears in countless variations and repetitions.

“The goal of science is to get as close to the truth as possible.” “To believe in and follow the direction that your truer self points to.” “To avoid uncomfortable truths.” “For example, two truths may compete with each other.” “Are all truths of equal value?”… … .

Why is truth so important? At some point, for the author, this question became a matter of power.

To write and to possess language means to be in a state where one can influence others, and sometimes even steal or destroy the lives of other beings.

As countless writers have taken parts of other people's lives and written them for themselves.

Just as Francis Bacon borrowed the perspective and grammar of the witch trials to argue that nature should be tortured and interrogated, this led later generations to view nature as “a mechanical being to be understood and conquered, not a living organism.”

The author is startled to see in his dream that he is unknowingly exerting such influence.

The sentences I poured out were beautiful and powerful.

Right, right.

People were very sympathetic.

Meanwhile, a friend who was staggering outside the bus collapsed.

I was so surprised while giving a speech that I got off the bus and came to his rescue.

Then people praised my actions even more.

They applauded him, saying that he was an ethical person who saved even trashy people.

Before I knew it, I started thinking of myself that way too.

While people were applauding, I suddenly woke up in horror, horrified by what I was doing as a character in a dream and as a narrator. (58)

The reason Hamina's intelligence in "Cut Me Off and Take Me Out" is so special is because her attitude toward and exercise of knowledge is so awakened.

He knows how to speak with reason in the midst of reality, like any intellectual, that truth should be measured by context and coordinates, not history and authority.

But what is surprising is that at the same time, he descends within himself and takes that knowledge and puts it into practice in his dreams.

Conscious of the complexity of truth and wary of the ripple effects of power and authority, he eventually ends up splitting himself apart and taking himself out, even in his dreams.

And then he tells us what happened in the language of dreams.

Waking from his dream, he knows how to be free by choosing to be vulnerable and humble.

It is possible to approach some truth in that way.

When the author was stuck on writing, he asked himself:

“If I could let go of the desire to prove my point right” and “let go of the desire to be remembered or known,” could I go further? Could we ask ourselves these questions as we seek to connect with others and the world?

As Leslie Jamison puts it, “Looking, looking, not looking away as soon as you get what you need.

(…) just watching them become more and more complex and subvert the narratives we have written for them.” (Leslie Jamieson, translated by Song Seom-byeol, Make Them Scream, Make Them Burn, Banbi, 2023, p. 206) According to poet Kim Hye-soon, whining, dying, inventing.

To put it in Ellen Cixous’s terms, “the activity of a being that does not return to itself (…) becoming a woman and at the same time one who cares and advances within the world” (Ellen Cixous, translated by Eun-ju Hwang, 『The Time of Respector』, Eulyoo Publishing, 2025, p. 133).

Could this be the answer to the question, “What do humans want to become?”

Can we each take our truths into a world of greater possibility?

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: November 20, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 424 pages | 568g | 141*220*24mm

- ISBN13: 9791199533202

- ISBN10: 1199533203

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)