Mitochondria

|

Description

Book Introduction

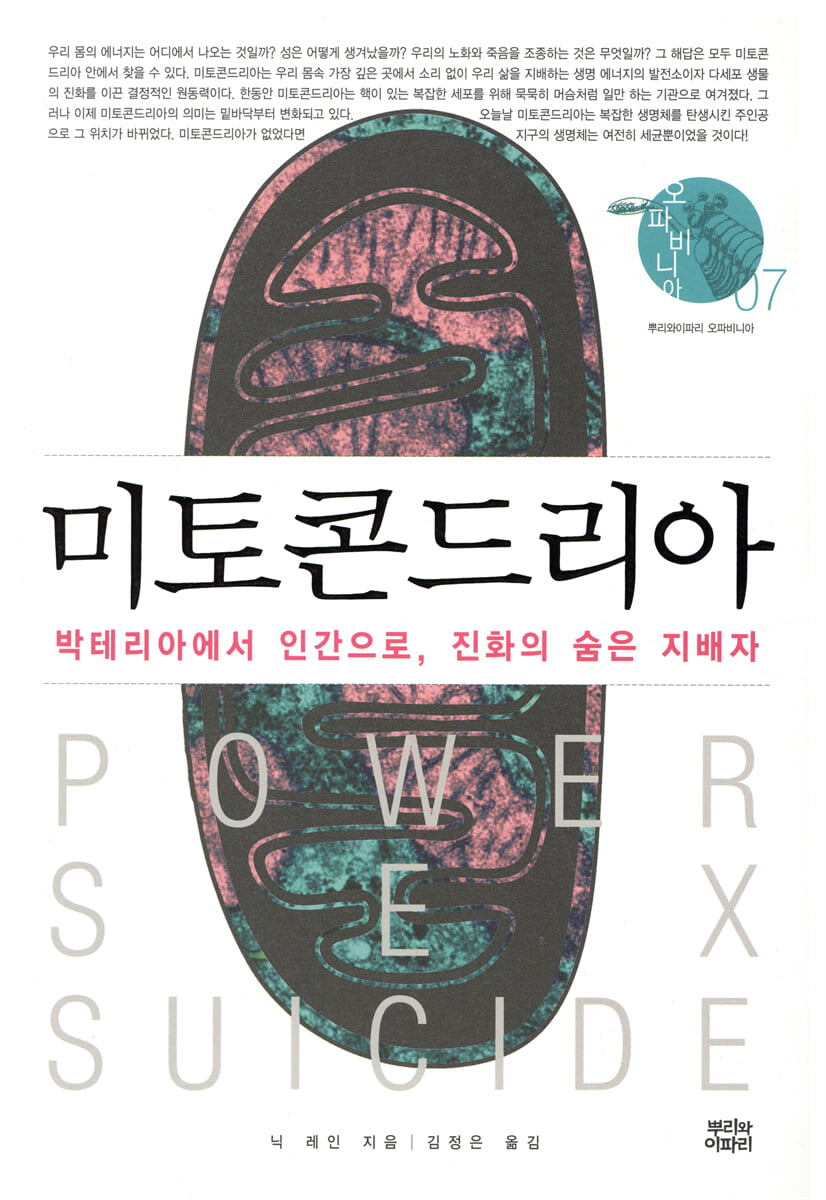

The seventh book in the "Roots and Leaves Opabinia" series, "Mitochondria: From Bacteria to Humans, Evolution's Hidden Masters," is filled with illustrations and content that anyone interested in biology will find thrilling as they piece together the puzzle from cutting-edge research.

Mitochondria are tiny organelles that produce almost all of the energy we use, and it's amazing how these tiny powerhouses control our lives.

Each cell contains an average of 300 to 400 mitochondria, and the total number in the entire body reaches 100 trillion.

Scientists argue that without the enslavement of mitochondria, we would all still be single-celled bacteria.

In fact, the importance of mitochondria is beyond imagination.

Today, mitochondria are at the center of diverse research fields covering prehistoric anthropology, genetic diseases, apoptosis, infertility, aging, bioenergetics, sex, and eukaryotic cells.

Author Nick Lane looks at our world through the lens of mitochondria, seeking answers to some of biology's most pressing questions: the formation of complexity, the origin of life, sex and fertility, death, and the prospect of eternal life.

Mitochondria are tiny organelles that produce almost all of the energy we use, and it's amazing how these tiny powerhouses control our lives.

Each cell contains an average of 300 to 400 mitochondria, and the total number in the entire body reaches 100 trillion.

Scientists argue that without the enslavement of mitochondria, we would all still be single-celled bacteria.

In fact, the importance of mitochondria is beyond imagination.

Today, mitochondria are at the center of diverse research fields covering prehistoric anthropology, genetic diseases, apoptosis, infertility, aging, bioenergetics, sex, and eukaryotic cells.

Author Nick Lane looks at our world through the lens of mitochondria, seeking answers to some of biology's most pressing questions: the formation of complexity, the origin of life, sex and fertility, death, and the prospect of eternal life.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

List of Figures | Acknowledgments

Introduction: Mitochondria: The Hidden Rulers of the World

Part 1: The Hopeful Monster: The Origin of Eukaryotic Cells

1.

The Deepest Rift of Evolution | 2.

In Search of Ancestors | 3.

hydrogen hypothesis

Part 2: The Power of Life: Proton Power and the Origin of Life

4.

The Meaning of Breathing | 5.

Proton Power | 6.

Origin of Life

Part 3: Insider Trading: The Foundations of Complexity

7.

Why are bacteria simple? | 8.

Mitochondria and Complexity

Part 4: Power Laws: Size and Complexity

9.

The Power Law in Biology | 10.

The Great Transformation of Homeotherms

Part 5: Murder or Suicide: The Uneasy Birth of the Individual

11.

Conflict within the body | 12.

Formation of an object

Part 6: The War Between the Sexes: Paleoanthropology and the Nature of Sex (341)

13.

Gender imbalance | 14.

A Side of Sexuality Revealed by Paleoanthropology | 15.

Why there must be positivity

Part 7: The Clock of Life: Mitochondria and Aging

16.

Mitochondrial Aging Theory | 17.

The disappearance of self-regulating devices | 18.

A cure for aging?

Epilogue | Translator's Note | Glossary | Further Reading | Index

Introduction: Mitochondria: The Hidden Rulers of the World

Part 1: The Hopeful Monster: The Origin of Eukaryotic Cells

1.

The Deepest Rift of Evolution | 2.

In Search of Ancestors | 3.

hydrogen hypothesis

Part 2: The Power of Life: Proton Power and the Origin of Life

4.

The Meaning of Breathing | 5.

Proton Power | 6.

Origin of Life

Part 3: Insider Trading: The Foundations of Complexity

7.

Why are bacteria simple? | 8.

Mitochondria and Complexity

Part 4: Power Laws: Size and Complexity

9.

The Power Law in Biology | 10.

The Great Transformation of Homeotherms

Part 5: Murder or Suicide: The Uneasy Birth of the Individual

11.

Conflict within the body | 12.

Formation of an object

Part 6: The War Between the Sexes: Paleoanthropology and the Nature of Sex (341)

13.

Gender imbalance | 14.

A Side of Sexuality Revealed by Paleoanthropology | 15.

Why there must be positivity

Part 7: The Clock of Life: Mitochondria and Aging

16.

Mitochondrial Aging Theory | 17.

The disappearance of self-regulating devices | 18.

A cure for aging?

Epilogue | Translator's Note | Glossary | Further Reading | Index

Into the book

In the past 20 years or so, new aspects of mitochondria have been discovered in the scientific community, but they may be somewhat unfamiliar to the general public.

The most important of these is programmed cell suicide, apoptosis.

Every cell commits suicide for the greater good, that is, for the whole body.

Since the mid-1990s, scientists have discovered that it is mitochondria, not nuclear genes, that determine apoptosis.

The result was unexpected.

Apoptosis has important implications in medical research.

This is because the fundamental cause of cancer is that apoptosis does not occur in situations where it should.

Instead of focusing on nuclear genes, many scientists are now exploring different ways to manipulate mitochondria.

--- P.18

How complex eukaryotic cells came to be is also a matter of heated debate.

The prevailing theory is that a primitive eukaryotic cell, which had been evolving little by little, one day swallowed a bacterium, and this bacterium became dependent on the cell over several generations, eventually becoming part of a complete cell and evolving into mitochondria.

According to this hypothesis, it is predicted that the common ancestor of all of us was a primitive eukaryotic single-celled organism without mitochondria.

This primitive eukaryotic single-celled organism provides evidence of cell structure before mitochondria were 'captured' and utilized.

However, more than a decade of meticulous genetic analysis has revealed that every eukaryotic cell known to date either has mitochondria or once did, even if they no longer do.

This shows that the origin of eukaryotic cells is closely related to the origin of mitochondria.

The two events occurred simultaneously or in unison.

If this is true, mitochondria would not only have been necessary for the evolution of multicellular organisms, but would have been necessary from the very beginning when the eukaryotic cells that make up multicellular organisms were first created.

If this is also true, it follows that all life on Earth could not have evolved beyond the bacterial level without mitochondria.

--- PP.19~20

A more subtle aspect of mitochondria has to do with differences between the sexes.

In fact, without mitochondria, there would be no sex.

The surname is a difficult problem that everyone knows about but no one has been able to solve.

For a child to be born through sexual reproduction, two people are needed: a father and a mother.

On the other hand, in the case of asexual or parthenogenetic reproduction, only the mother is sufficient.

The father role is not only unnecessary, it is a waste of resources and space.

Moreover, when sex is seen as a means of reproduction, having two sexes means that one must find a mate among half of the entire population.

It would be better if everyone had the same last name, regardless of whether they gave birth, or if everyone had different last names.

Two sexes is the worst of all possibilities.

The answer to this riddle also has to do with mitochondria.

This answer is not widely known to the general public, but it was discovered in the late 1970s and is now accepted as established theory among scholars.

The reason we need two sexes is because females are differentiated to pass on their mitochondria through their eggs, while males are differentiated to not pass on their mitochondria through their sperm.

--- P.20

All truly multicellular organisms on Earth are made up of eukaryotic cells, which are cells with a nucleus.

The evolution of this complex cell is shrouded in mystery and may be one of the most improbable events in the history of life.

The most crucial moment in this event is not the moment the nucleus is formed, but the moment when the two cells become one.

One cell engulfed another, creating an unidentified cell containing mitochondria.

However, it is not uncommon for one cell to engulf another.

What makes this one-time eukaryotic fusion so special? --- P.39

Recent research suggests that the acquisition of mitochondria was far more significant than simply providing sufficient power for complex eukaryotic cells that already had gene-packed nuclei.

This event made the evolution of complex eukaryotic cells possible in a flash.

If the union with mitochondria had not occurred, not only would we not be here today, but neither would other intelligent life forms, nor truly multicellular organisms, have appeared on this planet.

--- PP.48~49

Bacteria have colonized the Earth for two billion years, forming colonies in every environment imaginable—and some unexpected ones.

Even today, the biomass of bacteria exceeds the biomass of all multicellular organisms combined.

However, there are several reasons why bacteria could never evolve into the large multicellular organisms we encounter along the way.

On the other hand, eukaryotic cells, which appeared much later than bacteria in the mainstream view, created a huge source of life that gave rise to all life around us in a period of only a few hundred million years, a fraction of the time that bacteria lived.

--- P.51

The two theories I believe are most likely for the origin of eukaryotic cells are the 'mainstream view' and the 'hydrogen hypothesis'.

The mainstream view is a development of a hypothesis first conceived by Lynn Margulis, with Oxford University biologist Tom Cavalier-Smith playing a major role in establishing the framework.

Few scholars have understood the molecular structure and evolutionary relationships of cells as well as Cavalier Smith.

He put forward numerous important and controversial theories regarding cellular evolution.

The hydrogen hypothesis, a theory completely different from the mainstream view, was strongly advocated by Bill Martin, an American biochemist at Heinrich-Heine University in Düsseldorf, Germany.

Martin, a geneticist, was more interested in the biochemical than the morphological aspects of studying the origins of eukaryotes.

--- P.64

One sunny morning, two billion years ago, a simple creature, a cousin of today's Archaea, swallowed a bacterium but for some reason was unable to digest it.

The bacteria survived and multiplied inside the Archaea that had engulfed them.

Whatever the mutual benefit, this secret alliance ultimately gave rise to all modern-day eukaryotes with mitochondria, including the plants, animals, and fungi we know so well.

--- P.76

While it's still possible that genuine Archaea still exist somewhere, waiting to be discovered, the prevailing opinion today is that the entire group of Archaea is a myth.

All eukaryotes studied have or once had mitochondria.

If we trust the evidence, there is no primitive Archaea anywhere.

And assuming this is true, the union of mitochondria and eukaryotes would have begun right at the very birth of eukaryotes, and the two would have been so closely linked that they could not be considered separately.

This union that allowed eukaryotes to flourish was a one-time event.

--- P.81

Long ago, in the deep ocean, where there was little oxygen, a methanogenic archaea and an alphaproteobacteria lived side by side.

Alphaproteobacteria, which were able to move, moved busily around in search of food, and occasionally fermented their food (the waste products of other bacteria) to produce energy, releasing hydrogen and carbon dioxide as waste.

The methanogenic archaea could make anything they needed from this waste, so the two lived happily ever after in a very comfortable and comfortable relationship.

Methanogens and Alphaproteobacteria grew closer every day, and Methanogens gradually changed their appearance to embrace their benefactor.

This change in shape can be seen in Figure 3.

As time went on, the poor, suffocatingly surrounded Alphaproteobacteria had little surface left to absorb food.

If I didn't find a way, I would have starved to death, but I was held tightly by the methanogenic archaea and couldn't escape.

Now the Alphaproteobacteria had no choice but to enter the body of the methanogenic archaea.

Then, the two could continue their comfortable relationship as the methanogenic archaea could absorb the necessary food through its surface.

So, the alphaproteobacteria entered the body of the methanogenic archaea.

--- P.96

The story doesn't end here.

A surprising ending awaits you now.

Having acquired two sets of genes through horizontal gene transfer, methanogenic archaea can now do anything.

It is now possible to absorb nutrients from the surroundings and ferment those nutrients to create energy.

Just as the ugly duckling turned into a swan, methanogenic archaea no longer need to remain methanogenic archaea.

Once trapped by their sole source of energy, producing only methane, they are now free to roam.

There was no need to avoid oxygen-rich environments either.

Moreover, loitering around in an oxygen-rich environment gave the alphaproteobacteria in their bodies a greater advantage, as they could use the oxygen to produce more energy more effectively.

Now all the host cell (no longer called a methanogenic archaea) needed was a faucet, an ATP pump.

Simply plug this faucet into the membrane of an alphaproteobacteria and the world will become your stage. The ATP pump is a truly groundbreaking creation of eukaryotes, and if we trust the genetic sequences of different eukaryotic groups, it was created early in the eukaryotic union.

The answer to the origin of life, the universe, and all things, namely eukaryotic cells, ultimately comes down to simple gene transfer.

--- P.100

The eukaryotic lifestyle is very energy-intensive.

The activity of changing shape and enveloping prey to catch and consume it consumes a lot of energy.

The only eukaryotes that can survive without mitochondria are parasites that live in the bodies of other organisms.

Besides, they require almost nothing to do.

However, the form must be changed.

In the next few chapters, we will take a closer look at how eukaryotes live.

All these changes, including morphological changes using a dynamic cytoskeleton, growth, accumulation of massive amounts of DNA, sex, and multicellularity, were possible because of mitochondria.

Therefore, in the case of bacteria, this is something that cannot happen, and even if it could happen, the probability is very small.

The reason has to do with the sophisticated energy production process that takes place across the membrane.

The methods of energy production in bacteria and mitochondria are essentially the same.

However, there is a difference in that in mitochondria, the process takes place inside the cell, whereas in bacteria, it uses the cell membrane.

The internalization of energy production not only made eukaryotic evolution possible, but also shed light on the origin of life itself.

--- PP.104~105

The energy production process that takes place inside mitochondria is one of the most bizarre mechanisms in biology, and its discovery rivals that of Darwin and Einstein.

Mitochondria generate power by creating an electrical potential difference by transporting protons across a biological membrane that is only a few nanometers thick.

This proton's momentum generates energy in the form of ATP as it passes through mushroom-shaped proteins in the membrane, which are called the fundamental particles of life.

This groundbreaking mechanism, like DNA, is fundamental to life and allows us to see into the origins of all life on Earth.

--- P.107

At first, not many people accepted the importance of ATP.

However, the importance of ATP was established through the work of Fritz Lipmann and Herman Kalckar in Copenhagen in the 1930s, and in 1941 (this time in the United States) they declared ATP to be the 'universal energy currency' of life.

Given that it was the 1940s, it would have been a bold claim that could easily backfire and even be detrimental to one's career.

But surprisingly, this claim was basically correct: ATP was found in all types of cells, including plants, animals, fungi, and bacteria.

In the 1940s, it was known that ATP was produced only through fermentation and respiration, but in the 1950s, photosynthesis was added to this.

Solar energy is used to produce ATP through photosynthesis.

Therefore, the fact that ATP is produced in all three major energy pathways of life—respiration, fermentation, and photosynthesis—is another meaningful example of the fundamental unity of life.

--- PP.128~129

Bacteria fundamentally utilize proton motive power. Although ATP is considered the universal energy currency, it is not used everywhere in the cell.

Proton motive power, rather than ATP, is primarily used for bacterial homeostasis (active transport of substances in and out of the cell) and locomotion (propulsion using flagella).

This fact that proton motive force is used where it is absolutely necessary to sustain life explains why the respiratory chain releases more protons than are needed to synthesize ATP, and also explains why it is impossible to determine how many ATP molecules are created when a single electron passes through the respiratory chain.

Proton motive force underlies life in many ways, including ATP synthesis.

And what has been revealed so far is only a small part.

--- P.147

You may be wondering:

Why haven't bacteria evolved beyond bacteria? Why haven't bacteria, after 4 billion years of evolution, created truly multicellular organisms—intelligent bacteria? Why did the evolution of eukaryotes require the union of archaea and bacteria? Couldn't eukaryotes have simply evolved from bacteria or archaea, gradually increasing in complexity? In Part 3, we will explore the answers to these long-standing mysteries and the implications they hold for the eukaryotic lineage that gave rise to plants and animals.

The significance is related to the fundamental nature of energy production using chemiosmosis, which can only occur when surrounded by a membrane.

--- P.164

Bacteria have ruled the Earth for 2 billion years.

Bacteria have evolved to a point where their biochemical capabilities are virtually limitless, but they haven't figured out how to grow in size or complexity.

Life on other planets may also be trapped in the same trap as bacteria.

Life on Earth began to grow in size and complexity when mitochondria took over energy production.

So why didn't bacteria incorporate their own energy production system into their bodies? The answer lies in a two-billion-year-old paradox: mitochondrial DNA, a persistent, enduring gene that persists through the ages.

---- P.165

I don't think bacteria can evolve into eukaryotes through natural selection alone.

Symbiosis was necessary to bridge the impassable gap between bacteria and eukaryotes, and the union of mitochondria was essential to sowing the seeds of complexity.

Without mitochondria, complex life would not have emerged; without symbiosis, there would be no mitochondria; without the mitochondrial union, we would not have been more than just bacteria.

Whether or not symbiosis is Darwinian, understanding why symbiotic mitochondria are necessary is paramount to understanding our past and where we stand today.

--- P.175

Just as bacteria discard genes that make them resistant to antibiotics, they also mercilessly discard other genes that are no longer needed at the moment.

Although genes that can be moved around, such as plasmids, can be more easily deleted, bacteria can also delete genes located on the main chromosome.

Any gene that is not constantly used can disappear through random mutations and selection to speed up replication.

The fact that bacteria have relatively few 'junk' DNA despite having fewer genes than eukaryotes suggests the effect this process has on the bacterial primary chromosome.

The reason germs are small and clutter-free is because we immediately throw away the luggage we don't need.

--- P.185

Breathing can be said to be the very essence of mitochondria's existence.

Breathing rate changes very sensitively depending on the situation.

It depends on whether we are awake, sleeping, doing aerobic exercise, sitting still, writing, or kicking a ball.

When such a sudden change in circumstances occurs, mitochondria must adapt to the change at the molecular level.

The demands of changing circumstances are so significant and so volatile that they are difficult to regulate by distant bureaucratic nuclear genes.

Similar sudden changes in needs occur not only in animals but also in plants, fungi, and microorganisms, which are much more sensitive to environmental changes (such as changes in oxygen concentration or temperature) at the molecular level.

So, Allen's argument is that mitochondria need to maintain genetic outposts to effectively cope with these changes.

This is because only then can the redox reactions occurring in the mitochondrial membrane be strictly controlled by the genes based there.

--- P.214

Is life inherently predisposed to complexity? The force that propels organisms up the slope of increasing complexity lies somewhere other than genes.

Size and complexity are generally related.

As size increases, complexity is required both genetically and morphologically.

However, increasing size does not provide immediate benefits to living organisms.

As size increases, mitochondria increase, and more mitochondria means greater strength and increased metabolic efficiency.

Mitochondria are thought to have been a driving force in both evolutionary processes.

One is the accumulation of DNA and genes, which are essential for the advancement of complexity, and the other is the evolution of homeotherms, which are widespread on Earth.

--- P.229

When cells in the body run out of energy or are damaged, they are forced to commit suicide. This is called apoptosis.

When apoptosis occurs, cells sprout protrusions, undergo condensation, and undergo resorption.

If the apoptosis regulation process does not function properly, cancer can occur.

A conflict of interest arises between cells and the entire organism.

Apoptosis appears to be essential for the preservation and cohesion of the entire multicellular organism.

But how did cells, once independent entities, come to embrace death for a greater good? Today, apoptosis is governed by mitochondria, and their origins in bacterial ancestors suggest a history of death.

So, does this mean that the bond between individuals sprouted in the midst of fierce fighting? --- P.285

The idea that bacteria only cause disease is a misconception.

According to Margulis, evolution is largely an event that occurred between bacteria and can be explained through cooperation between bacteria.

This includes endosymbiosis, which became the basis of eukaryotic cells.

This type of cooperative relationship occurs primarily in bacteria, as it is not well suited to predatory behavior.

(Omitted) Bacteria have no choice but to compete for survival by competing for reproduction speed rather than mouth size.

In the reality of a food-scarce bacterial ecosystem, it is far more beneficial for organisms to survive off each other's byproducts than to fight over the same resources.

(Omitted) It should be kept in mind that a cooperative relationship can only continue when cooperation is mutually beneficial.

Whether we measure 'success' by the survival of cells or by the survival of genes, we can only see the survivors: the genes or cells that most successfully replicated themselves.

If a cell is extremely altruistic, it will disappear without a trace for the sake of other cells.

It's similar to the countless young war heroes who died fighting for their country without leaving behind a single child.

The point I'm making is that cooperation doesn't have to be altruistic.

Yet, a world of cooperation is far removed from the stereotype of nature as “a ferocious, bloody, tooth and claw,” as Tennyson put it.

Cooperation may not be altruistic, but it is not so "aggressive" as to conjure up images of blood dripping from the corners of the mouth.

/ The conflict between neo-Darwinists like Dawkins and Margulis is partly responsible for this contradiction.

As we have seen, Dawkins' concept of the selfish gene does not apply well to bacteria (and Dawkins did not even try to apply it).

But for Margulis, evolution is a carefully orchestrated picture of cooperation among bacteria. PP.

295~296

Both sperm and eggs pass on the genes contained in their nuclei, but under normal circumstances, only eggs pass on mitochondria to the next generation, along with the small but important genome they contain.

Using the characteristics of mitochondrial DNA, which is inherited through the maternal line, they also traced back to "Mitochondrial Eve," the ancestor of all humans who lived 170,000 years ago.

Recent data have challenged the principle of matrilineal inheritance of mitochondria, but have instead provided a new perspective on why mitochondria are primarily inherited through the maternal line.

This new perspective will help us understand why two sexes had to evolve.

--- P.341

Animals with higher metabolic rates tend to age more quickly and succumb to degenerative diseases such as cancer.

However, birds have high metabolic rates, long lifespans, and are not prone to these diseases.

The reason this exceptional phenomenon occurs is because the mitochondria of birds leak fewer free radicals.

So how is it that degenerative diseases, which at first glance seem unrelated to mitochondria, are affected by free radical leakage? A dynamic and novel phenomenon is slowly emerging.

Signals between damaged mitochondria and the nucleus determine the fate of the cell, and thus our own.

The most important of these is programmed cell suicide, apoptosis.

Every cell commits suicide for the greater good, that is, for the whole body.

Since the mid-1990s, scientists have discovered that it is mitochondria, not nuclear genes, that determine apoptosis.

The result was unexpected.

Apoptosis has important implications in medical research.

This is because the fundamental cause of cancer is that apoptosis does not occur in situations where it should.

Instead of focusing on nuclear genes, many scientists are now exploring different ways to manipulate mitochondria.

--- P.18

How complex eukaryotic cells came to be is also a matter of heated debate.

The prevailing theory is that a primitive eukaryotic cell, which had been evolving little by little, one day swallowed a bacterium, and this bacterium became dependent on the cell over several generations, eventually becoming part of a complete cell and evolving into mitochondria.

According to this hypothesis, it is predicted that the common ancestor of all of us was a primitive eukaryotic single-celled organism without mitochondria.

This primitive eukaryotic single-celled organism provides evidence of cell structure before mitochondria were 'captured' and utilized.

However, more than a decade of meticulous genetic analysis has revealed that every eukaryotic cell known to date either has mitochondria or once did, even if they no longer do.

This shows that the origin of eukaryotic cells is closely related to the origin of mitochondria.

The two events occurred simultaneously or in unison.

If this is true, mitochondria would not only have been necessary for the evolution of multicellular organisms, but would have been necessary from the very beginning when the eukaryotic cells that make up multicellular organisms were first created.

If this is also true, it follows that all life on Earth could not have evolved beyond the bacterial level without mitochondria.

--- PP.19~20

A more subtle aspect of mitochondria has to do with differences between the sexes.

In fact, without mitochondria, there would be no sex.

The surname is a difficult problem that everyone knows about but no one has been able to solve.

For a child to be born through sexual reproduction, two people are needed: a father and a mother.

On the other hand, in the case of asexual or parthenogenetic reproduction, only the mother is sufficient.

The father role is not only unnecessary, it is a waste of resources and space.

Moreover, when sex is seen as a means of reproduction, having two sexes means that one must find a mate among half of the entire population.

It would be better if everyone had the same last name, regardless of whether they gave birth, or if everyone had different last names.

Two sexes is the worst of all possibilities.

The answer to this riddle also has to do with mitochondria.

This answer is not widely known to the general public, but it was discovered in the late 1970s and is now accepted as established theory among scholars.

The reason we need two sexes is because females are differentiated to pass on their mitochondria through their eggs, while males are differentiated to not pass on their mitochondria through their sperm.

--- P.20

All truly multicellular organisms on Earth are made up of eukaryotic cells, which are cells with a nucleus.

The evolution of this complex cell is shrouded in mystery and may be one of the most improbable events in the history of life.

The most crucial moment in this event is not the moment the nucleus is formed, but the moment when the two cells become one.

One cell engulfed another, creating an unidentified cell containing mitochondria.

However, it is not uncommon for one cell to engulf another.

What makes this one-time eukaryotic fusion so special? --- P.39

Recent research suggests that the acquisition of mitochondria was far more significant than simply providing sufficient power for complex eukaryotic cells that already had gene-packed nuclei.

This event made the evolution of complex eukaryotic cells possible in a flash.

If the union with mitochondria had not occurred, not only would we not be here today, but neither would other intelligent life forms, nor truly multicellular organisms, have appeared on this planet.

--- PP.48~49

Bacteria have colonized the Earth for two billion years, forming colonies in every environment imaginable—and some unexpected ones.

Even today, the biomass of bacteria exceeds the biomass of all multicellular organisms combined.

However, there are several reasons why bacteria could never evolve into the large multicellular organisms we encounter along the way.

On the other hand, eukaryotic cells, which appeared much later than bacteria in the mainstream view, created a huge source of life that gave rise to all life around us in a period of only a few hundred million years, a fraction of the time that bacteria lived.

--- P.51

The two theories I believe are most likely for the origin of eukaryotic cells are the 'mainstream view' and the 'hydrogen hypothesis'.

The mainstream view is a development of a hypothesis first conceived by Lynn Margulis, with Oxford University biologist Tom Cavalier-Smith playing a major role in establishing the framework.

Few scholars have understood the molecular structure and evolutionary relationships of cells as well as Cavalier Smith.

He put forward numerous important and controversial theories regarding cellular evolution.

The hydrogen hypothesis, a theory completely different from the mainstream view, was strongly advocated by Bill Martin, an American biochemist at Heinrich-Heine University in Düsseldorf, Germany.

Martin, a geneticist, was more interested in the biochemical than the morphological aspects of studying the origins of eukaryotes.

--- P.64

One sunny morning, two billion years ago, a simple creature, a cousin of today's Archaea, swallowed a bacterium but for some reason was unable to digest it.

The bacteria survived and multiplied inside the Archaea that had engulfed them.

Whatever the mutual benefit, this secret alliance ultimately gave rise to all modern-day eukaryotes with mitochondria, including the plants, animals, and fungi we know so well.

--- P.76

While it's still possible that genuine Archaea still exist somewhere, waiting to be discovered, the prevailing opinion today is that the entire group of Archaea is a myth.

All eukaryotes studied have or once had mitochondria.

If we trust the evidence, there is no primitive Archaea anywhere.

And assuming this is true, the union of mitochondria and eukaryotes would have begun right at the very birth of eukaryotes, and the two would have been so closely linked that they could not be considered separately.

This union that allowed eukaryotes to flourish was a one-time event.

--- P.81

Long ago, in the deep ocean, where there was little oxygen, a methanogenic archaea and an alphaproteobacteria lived side by side.

Alphaproteobacteria, which were able to move, moved busily around in search of food, and occasionally fermented their food (the waste products of other bacteria) to produce energy, releasing hydrogen and carbon dioxide as waste.

The methanogenic archaea could make anything they needed from this waste, so the two lived happily ever after in a very comfortable and comfortable relationship.

Methanogens and Alphaproteobacteria grew closer every day, and Methanogens gradually changed their appearance to embrace their benefactor.

This change in shape can be seen in Figure 3.

As time went on, the poor, suffocatingly surrounded Alphaproteobacteria had little surface left to absorb food.

If I didn't find a way, I would have starved to death, but I was held tightly by the methanogenic archaea and couldn't escape.

Now the Alphaproteobacteria had no choice but to enter the body of the methanogenic archaea.

Then, the two could continue their comfortable relationship as the methanogenic archaea could absorb the necessary food through its surface.

So, the alphaproteobacteria entered the body of the methanogenic archaea.

--- P.96

The story doesn't end here.

A surprising ending awaits you now.

Having acquired two sets of genes through horizontal gene transfer, methanogenic archaea can now do anything.

It is now possible to absorb nutrients from the surroundings and ferment those nutrients to create energy.

Just as the ugly duckling turned into a swan, methanogenic archaea no longer need to remain methanogenic archaea.

Once trapped by their sole source of energy, producing only methane, they are now free to roam.

There was no need to avoid oxygen-rich environments either.

Moreover, loitering around in an oxygen-rich environment gave the alphaproteobacteria in their bodies a greater advantage, as they could use the oxygen to produce more energy more effectively.

Now all the host cell (no longer called a methanogenic archaea) needed was a faucet, an ATP pump.

Simply plug this faucet into the membrane of an alphaproteobacteria and the world will become your stage. The ATP pump is a truly groundbreaking creation of eukaryotes, and if we trust the genetic sequences of different eukaryotic groups, it was created early in the eukaryotic union.

The answer to the origin of life, the universe, and all things, namely eukaryotic cells, ultimately comes down to simple gene transfer.

--- P.100

The eukaryotic lifestyle is very energy-intensive.

The activity of changing shape and enveloping prey to catch and consume it consumes a lot of energy.

The only eukaryotes that can survive without mitochondria are parasites that live in the bodies of other organisms.

Besides, they require almost nothing to do.

However, the form must be changed.

In the next few chapters, we will take a closer look at how eukaryotes live.

All these changes, including morphological changes using a dynamic cytoskeleton, growth, accumulation of massive amounts of DNA, sex, and multicellularity, were possible because of mitochondria.

Therefore, in the case of bacteria, this is something that cannot happen, and even if it could happen, the probability is very small.

The reason has to do with the sophisticated energy production process that takes place across the membrane.

The methods of energy production in bacteria and mitochondria are essentially the same.

However, there is a difference in that in mitochondria, the process takes place inside the cell, whereas in bacteria, it uses the cell membrane.

The internalization of energy production not only made eukaryotic evolution possible, but also shed light on the origin of life itself.

--- PP.104~105

The energy production process that takes place inside mitochondria is one of the most bizarre mechanisms in biology, and its discovery rivals that of Darwin and Einstein.

Mitochondria generate power by creating an electrical potential difference by transporting protons across a biological membrane that is only a few nanometers thick.

This proton's momentum generates energy in the form of ATP as it passes through mushroom-shaped proteins in the membrane, which are called the fundamental particles of life.

This groundbreaking mechanism, like DNA, is fundamental to life and allows us to see into the origins of all life on Earth.

--- P.107

At first, not many people accepted the importance of ATP.

However, the importance of ATP was established through the work of Fritz Lipmann and Herman Kalckar in Copenhagen in the 1930s, and in 1941 (this time in the United States) they declared ATP to be the 'universal energy currency' of life.

Given that it was the 1940s, it would have been a bold claim that could easily backfire and even be detrimental to one's career.

But surprisingly, this claim was basically correct: ATP was found in all types of cells, including plants, animals, fungi, and bacteria.

In the 1940s, it was known that ATP was produced only through fermentation and respiration, but in the 1950s, photosynthesis was added to this.

Solar energy is used to produce ATP through photosynthesis.

Therefore, the fact that ATP is produced in all three major energy pathways of life—respiration, fermentation, and photosynthesis—is another meaningful example of the fundamental unity of life.

--- PP.128~129

Bacteria fundamentally utilize proton motive power. Although ATP is considered the universal energy currency, it is not used everywhere in the cell.

Proton motive power, rather than ATP, is primarily used for bacterial homeostasis (active transport of substances in and out of the cell) and locomotion (propulsion using flagella).

This fact that proton motive force is used where it is absolutely necessary to sustain life explains why the respiratory chain releases more protons than are needed to synthesize ATP, and also explains why it is impossible to determine how many ATP molecules are created when a single electron passes through the respiratory chain.

Proton motive force underlies life in many ways, including ATP synthesis.

And what has been revealed so far is only a small part.

--- P.147

You may be wondering:

Why haven't bacteria evolved beyond bacteria? Why haven't bacteria, after 4 billion years of evolution, created truly multicellular organisms—intelligent bacteria? Why did the evolution of eukaryotes require the union of archaea and bacteria? Couldn't eukaryotes have simply evolved from bacteria or archaea, gradually increasing in complexity? In Part 3, we will explore the answers to these long-standing mysteries and the implications they hold for the eukaryotic lineage that gave rise to plants and animals.

The significance is related to the fundamental nature of energy production using chemiosmosis, which can only occur when surrounded by a membrane.

--- P.164

Bacteria have ruled the Earth for 2 billion years.

Bacteria have evolved to a point where their biochemical capabilities are virtually limitless, but they haven't figured out how to grow in size or complexity.

Life on other planets may also be trapped in the same trap as bacteria.

Life on Earth began to grow in size and complexity when mitochondria took over energy production.

So why didn't bacteria incorporate their own energy production system into their bodies? The answer lies in a two-billion-year-old paradox: mitochondrial DNA, a persistent, enduring gene that persists through the ages.

---- P.165

I don't think bacteria can evolve into eukaryotes through natural selection alone.

Symbiosis was necessary to bridge the impassable gap between bacteria and eukaryotes, and the union of mitochondria was essential to sowing the seeds of complexity.

Without mitochondria, complex life would not have emerged; without symbiosis, there would be no mitochondria; without the mitochondrial union, we would not have been more than just bacteria.

Whether or not symbiosis is Darwinian, understanding why symbiotic mitochondria are necessary is paramount to understanding our past and where we stand today.

--- P.175

Just as bacteria discard genes that make them resistant to antibiotics, they also mercilessly discard other genes that are no longer needed at the moment.

Although genes that can be moved around, such as plasmids, can be more easily deleted, bacteria can also delete genes located on the main chromosome.

Any gene that is not constantly used can disappear through random mutations and selection to speed up replication.

The fact that bacteria have relatively few 'junk' DNA despite having fewer genes than eukaryotes suggests the effect this process has on the bacterial primary chromosome.

The reason germs are small and clutter-free is because we immediately throw away the luggage we don't need.

--- P.185

Breathing can be said to be the very essence of mitochondria's existence.

Breathing rate changes very sensitively depending on the situation.

It depends on whether we are awake, sleeping, doing aerobic exercise, sitting still, writing, or kicking a ball.

When such a sudden change in circumstances occurs, mitochondria must adapt to the change at the molecular level.

The demands of changing circumstances are so significant and so volatile that they are difficult to regulate by distant bureaucratic nuclear genes.

Similar sudden changes in needs occur not only in animals but also in plants, fungi, and microorganisms, which are much more sensitive to environmental changes (such as changes in oxygen concentration or temperature) at the molecular level.

So, Allen's argument is that mitochondria need to maintain genetic outposts to effectively cope with these changes.

This is because only then can the redox reactions occurring in the mitochondrial membrane be strictly controlled by the genes based there.

--- P.214

Is life inherently predisposed to complexity? The force that propels organisms up the slope of increasing complexity lies somewhere other than genes.

Size and complexity are generally related.

As size increases, complexity is required both genetically and morphologically.

However, increasing size does not provide immediate benefits to living organisms.

As size increases, mitochondria increase, and more mitochondria means greater strength and increased metabolic efficiency.

Mitochondria are thought to have been a driving force in both evolutionary processes.

One is the accumulation of DNA and genes, which are essential for the advancement of complexity, and the other is the evolution of homeotherms, which are widespread on Earth.

--- P.229

When cells in the body run out of energy or are damaged, they are forced to commit suicide. This is called apoptosis.

When apoptosis occurs, cells sprout protrusions, undergo condensation, and undergo resorption.

If the apoptosis regulation process does not function properly, cancer can occur.

A conflict of interest arises between cells and the entire organism.

Apoptosis appears to be essential for the preservation and cohesion of the entire multicellular organism.

But how did cells, once independent entities, come to embrace death for a greater good? Today, apoptosis is governed by mitochondria, and their origins in bacterial ancestors suggest a history of death.

So, does this mean that the bond between individuals sprouted in the midst of fierce fighting? --- P.285

The idea that bacteria only cause disease is a misconception.

According to Margulis, evolution is largely an event that occurred between bacteria and can be explained through cooperation between bacteria.

This includes endosymbiosis, which became the basis of eukaryotic cells.

This type of cooperative relationship occurs primarily in bacteria, as it is not well suited to predatory behavior.

(Omitted) Bacteria have no choice but to compete for survival by competing for reproduction speed rather than mouth size.

In the reality of a food-scarce bacterial ecosystem, it is far more beneficial for organisms to survive off each other's byproducts than to fight over the same resources.

(Omitted) It should be kept in mind that a cooperative relationship can only continue when cooperation is mutually beneficial.

Whether we measure 'success' by the survival of cells or by the survival of genes, we can only see the survivors: the genes or cells that most successfully replicated themselves.

If a cell is extremely altruistic, it will disappear without a trace for the sake of other cells.

It's similar to the countless young war heroes who died fighting for their country without leaving behind a single child.

The point I'm making is that cooperation doesn't have to be altruistic.

Yet, a world of cooperation is far removed from the stereotype of nature as “a ferocious, bloody, tooth and claw,” as Tennyson put it.

Cooperation may not be altruistic, but it is not so "aggressive" as to conjure up images of blood dripping from the corners of the mouth.

/ The conflict between neo-Darwinists like Dawkins and Margulis is partly responsible for this contradiction.

As we have seen, Dawkins' concept of the selfish gene does not apply well to bacteria (and Dawkins did not even try to apply it).

But for Margulis, evolution is a carefully orchestrated picture of cooperation among bacteria. PP.

295~296

Both sperm and eggs pass on the genes contained in their nuclei, but under normal circumstances, only eggs pass on mitochondria to the next generation, along with the small but important genome they contain.

Using the characteristics of mitochondrial DNA, which is inherited through the maternal line, they also traced back to "Mitochondrial Eve," the ancestor of all humans who lived 170,000 years ago.

Recent data have challenged the principle of matrilineal inheritance of mitochondria, but have instead provided a new perspective on why mitochondria are primarily inherited through the maternal line.

This new perspective will help us understand why two sexes had to evolve.

--- P.341

Animals with higher metabolic rates tend to age more quickly and succumb to degenerative diseases such as cancer.

However, birds have high metabolic rates, long lifespans, and are not prone to these diseases.

The reason this exceptional phenomenon occurs is because the mitochondria of birds leak fewer free radicals.

So how is it that degenerative diseases, which at first glance seem unrelated to mitochondria, are affected by free radical leakage? A dynamic and novel phenomenon is slowly emerging.

Signals between damaged mitochondria and the nucleus determine the fate of the cell, and thus our own.

--- P.399

Publisher's Review

Where does our body's energy come from? How did sex arise? What controls our aging and death? The answers to these questions can all be found within the mitochondria.

Mitochondria are the powerhouses of life energy that silently govern our lives, located deep within our bodies, and are the decisive driving force behind the evolution of multicellular organisms.

For a long time, mitochondria were thought to be silent servants of complex cells with nuclei.

But now the meaning of mitochondria is changing from the ground up.

Today, mitochondria have taken their place as the main characters that gave birth to complex life forms.

Without mitochondria, life on Earth would still be just bacteria!

Everything about mitochondria, which hold the key to life and are more important and complex than we imagine!

Everyone has probably heard the name ‘mitochondria’ at least once.

Mitochondria are tiny organelles that produce almost all of the energy we use, and it's amazing how these tiny powerhouses control our lives.

Each cell contains an average of 300 to 400 mitochondria, and the total number in the entire body reaches 100 trillion.

Mitochondria are very small.

It takes 100 million mitochondria to gather together to form a single grain of sand! Mitochondrial evolution has essentially given life a turbocharged engine, always ready to be used and actively operated.

All animals must have mitochondria.

Even the slowest animals are no exception.

Even plants and algae that live in one place use mitochondria to amplify the secret sound of solar energy through photosynthesis.

Cells as complex as this one necessarily contain mitochondria.

Mitochondria resemble bacteria on the outside, but that's not the only difference.

Mitochondria were once true bacteria that lived independently and adapted to living within larger cells about 2 billion years ago.

The bacteria that dominated Earth for the previous two billion years were unable to create true complexity (perhaps this is still holding back life on other planets).

Afterwards, the union of two bacteria caused the Big Bang of evolution, and from then on, algae, fungi, plants and animals began to appear.

As a badge of honor that they were once independent organisms, mitochondria still clearly retain the characteristics of bacteria, including their DNA.

Since that fateful union, the twisted and unpredictable relationship between mitochondria and their host cells has produced one revolutionary evolutionary product after another.

Without mitochondria, the world we know would not exist.

The story of mitochondria is the story of life itself.

Meanwhile, some people may be more familiar with the term 'Mitochondrial Eve'.

Mitochondrial Eve is believed to be the most recent common ancestor of all humans living today.

If we trace our genetic material back through the maternal line—that is, through our mother's mother, and her mother's mother, and so on, all the way back to the distant past—we find Mitochondrial Eve.

Mitochondrial Eve, the mother of all mothers, is believed to have lived on the African continent about 170,000 years ago and is therefore also known as 'African Eve'.

Genetic ancestry can be traced in the same way, because of the tiny amount of genes contained in every mitochondrion.

This gene is passed on to the next generation only through eggs, not sperm.

In other words, since mitochondrial genes serve as a maternal surname, it is possible to trace ancestors along the maternal line.

Scientists argue that without the enslavement of mitochondria, we would all still be single-celled bacteria.

In fact, the importance of mitochondria is beyond imagination.

Today, mitochondria are at the center of diverse research fields covering prehistoric anthropology, genetic diseases, apoptosis, infertility, aging, bioenergetics, sex, and eukaryotic cells.

The seventh book in the "Roots and Flies Opabinia" series, "Mitochondria: From Bacteria to Humans, Evolution's Hidden Masters," fills the canvas with a thrilling picture for anyone interested in biology, as it puts together puzzle pieces from cutting-edge research.

It also contributes greatly to the views and discussions related to evolution.

In short, this book looks at the world we live in from the perspective of mitochondria and seeks answers to some of biology's most pressing questions: the formation of complexity, the origin of life, sex and fertility, death, and the prospect of eternal life.

As a result, a new perspective on the meaning of life opens up!

Mitochondria are the powerhouses of life energy that silently govern our lives, located deep within our bodies, and are the decisive driving force behind the evolution of multicellular organisms.

For a long time, mitochondria were thought to be silent servants of complex cells with nuclei.

But now the meaning of mitochondria is changing from the ground up.

Today, mitochondria have taken their place as the main characters that gave birth to complex life forms.

Without mitochondria, life on Earth would still be just bacteria!

Everything about mitochondria, which hold the key to life and are more important and complex than we imagine!

Everyone has probably heard the name ‘mitochondria’ at least once.

Mitochondria are tiny organelles that produce almost all of the energy we use, and it's amazing how these tiny powerhouses control our lives.

Each cell contains an average of 300 to 400 mitochondria, and the total number in the entire body reaches 100 trillion.

Mitochondria are very small.

It takes 100 million mitochondria to gather together to form a single grain of sand! Mitochondrial evolution has essentially given life a turbocharged engine, always ready to be used and actively operated.

All animals must have mitochondria.

Even the slowest animals are no exception.

Even plants and algae that live in one place use mitochondria to amplify the secret sound of solar energy through photosynthesis.

Cells as complex as this one necessarily contain mitochondria.

Mitochondria resemble bacteria on the outside, but that's not the only difference.

Mitochondria were once true bacteria that lived independently and adapted to living within larger cells about 2 billion years ago.

The bacteria that dominated Earth for the previous two billion years were unable to create true complexity (perhaps this is still holding back life on other planets).

Afterwards, the union of two bacteria caused the Big Bang of evolution, and from then on, algae, fungi, plants and animals began to appear.

As a badge of honor that they were once independent organisms, mitochondria still clearly retain the characteristics of bacteria, including their DNA.

Since that fateful union, the twisted and unpredictable relationship between mitochondria and their host cells has produced one revolutionary evolutionary product after another.

Without mitochondria, the world we know would not exist.

The story of mitochondria is the story of life itself.

Meanwhile, some people may be more familiar with the term 'Mitochondrial Eve'.

Mitochondrial Eve is believed to be the most recent common ancestor of all humans living today.

If we trace our genetic material back through the maternal line—that is, through our mother's mother, and her mother's mother, and so on, all the way back to the distant past—we find Mitochondrial Eve.

Mitochondrial Eve, the mother of all mothers, is believed to have lived on the African continent about 170,000 years ago and is therefore also known as 'African Eve'.

Genetic ancestry can be traced in the same way, because of the tiny amount of genes contained in every mitochondrion.

This gene is passed on to the next generation only through eggs, not sperm.

In other words, since mitochondrial genes serve as a maternal surname, it is possible to trace ancestors along the maternal line.

Scientists argue that without the enslavement of mitochondria, we would all still be single-celled bacteria.

In fact, the importance of mitochondria is beyond imagination.

Today, mitochondria are at the center of diverse research fields covering prehistoric anthropology, genetic diseases, apoptosis, infertility, aging, bioenergetics, sex, and eukaryotic cells.

The seventh book in the "Roots and Flies Opabinia" series, "Mitochondria: From Bacteria to Humans, Evolution's Hidden Masters," fills the canvas with a thrilling picture for anyone interested in biology, as it puts together puzzle pieces from cutting-edge research.

It also contributes greatly to the views and discussions related to evolution.

In short, this book looks at the world we live in from the perspective of mitochondria and seeks answers to some of biology's most pressing questions: the formation of complexity, the origin of life, sex and fertility, death, and the prospect of eternal life.

As a result, a new perspective on the meaning of life opens up!

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: January 23, 2009

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 536 pages | 884g | 153*224*35mm

- ISBN13: 9788990024886

- ISBN10: 8990024889

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)