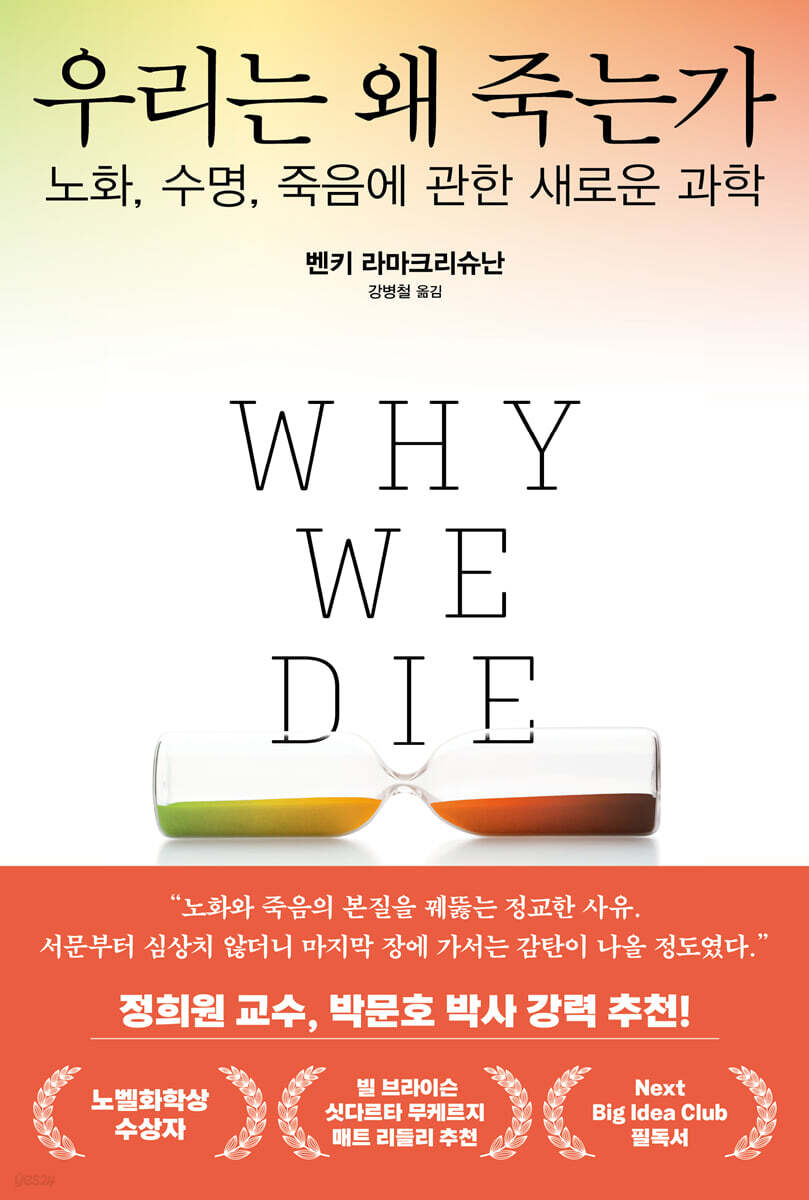

Why do we die

|

Description

Book Introduction

“A sophisticated thought that penetrates the essence of aging and death.

“It was unusual from the introduction, and by the last chapter, I was amazed.”

★ Highly recommended by Professor Jeong Hee-won and Dr. Park Moon-ho! ★

Nobel Prize-winning molecular biologist Venky Ramakrishnan tells us

The Science of Aging, Longevity, Death, and the Pursuit of Immortality

What is death? Why on earth are we destined to die? Will humanity ever be able to overcome disease and death? Even if we could live forever, would we really want to? In this era of a biological revolution, a paradigm shift in aging science, we've compiled the past 50 years of research by the world's leading aging scientists.

We examine the major aging mechanisms one by one, taking a balanced look at what efforts are being made to slow them down and what obstacles must be overcome.

He also critically examines star scientists and renowned biotechnology companies, and goes on to explore whether death has a biologically necessary purpose, the various social problems that life extension will bring, and the ethical costs of trying to live forever, all while presenting a story filled with extraordinary insight as an intellectual.

Beyond the fervent expectations and rosy hopes for an extended healthy lifespan, it allows us to look at aging and death with new eyes.

From meticulous research to captivating storytelling and deep philosophical reflection, this masterpiece shines with the mature insights of one of our generation's leading molecular biologists!

“It was unusual from the introduction, and by the last chapter, I was amazed.”

★ Highly recommended by Professor Jeong Hee-won and Dr. Park Moon-ho! ★

Nobel Prize-winning molecular biologist Venky Ramakrishnan tells us

The Science of Aging, Longevity, Death, and the Pursuit of Immortality

What is death? Why on earth are we destined to die? Will humanity ever be able to overcome disease and death? Even if we could live forever, would we really want to? In this era of a biological revolution, a paradigm shift in aging science, we've compiled the past 50 years of research by the world's leading aging scientists.

We examine the major aging mechanisms one by one, taking a balanced look at what efforts are being made to slow them down and what obstacles must be overcome.

He also critically examines star scientists and renowned biotechnology companies, and goes on to explore whether death has a biologically necessary purpose, the various social problems that life extension will bring, and the ethical costs of trying to live forever, all while presenting a story filled with extraordinary insight as an intellectual.

Beyond the fervent expectations and rosy hopes for an extended healthy lifespan, it allows us to look at aging and death with new eyes.

From meticulous research to captivating storytelling and deep philosophical reflection, this masterpiece shines with the mature insights of one of our generation's leading molecular biologists!

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

preface

Chapter 1: Immortal Genes and Disposable Bodies

Chapter 2: Live boldly and briefly

Chapter 3 Destruction of the Main Controller

Problem at the end of Chapter 4

Chapter 5: Resetting Your Biological Clock

Chapter 6: Waste Recycling

Chapter 7: Less is More

Chapter 8: The Lesson of a Small Bug

Chapter 9: The Stowaways in Our Bodies

Chapter 10 Pain and Vampire Blood

Chapter 11: Madman or Prophet?

Chapter 12: Should we live forever?

Acknowledgements

main

Translator's Note

Search

Chapter 1: Immortal Genes and Disposable Bodies

Chapter 2: Live boldly and briefly

Chapter 3 Destruction of the Main Controller

Problem at the end of Chapter 4

Chapter 5: Resetting Your Biological Clock

Chapter 6: Waste Recycling

Chapter 7: Less is More

Chapter 8: The Lesson of a Small Bug

Chapter 9: The Stowaways in Our Bodies

Chapter 10 Pain and Vampire Blood

Chapter 11: Madman or Prophet?

Chapter 12: Should we live forever?

Acknowledgements

main

Translator's Note

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

What will society look like if such technologies become widespread? Could it be that we are sleepwalking into the future, ignoring the social, economic, and political consequences of living much longer than we do now? Given recent advances and the enormous investment in aging research, we must consider where this research will lead us and what choices it will offer regarding human limitations.

--- p.16~17

Why on earth does death exist? Why can't we just live forever?

The 20th-century Russian geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky wrote:

“If you don’t look at biology through the lens of evolution, none of it makes sense.” In biology, whenever the question “why does something happen?” is asked, the ultimate answer is always “because it evolved that way.”

When I first thought about the question, 'Why do we die?', I naively thought this:

Perhaps death is nature's way of ensuring the survival of genes, preventing old individuals from needlessly surviving and competing for resources so that new generations can thrive and procreate. Furthermore, each individual in the new generation possesses a different genetic combination than its parents.

Could it be that by constantly shuffling the cards of life, we help the survival of the entire species?

This idea has been around at least since the time of the Roman poet Lucretius, who lived in the first century BC.

It has that much appeal.

But I was wrong.

--- p.32~33

In 1825, Benjamin Gompertz, a self-taught British mathematician, studied the relationship between mortality and age.

Since the study was commissioned by an insurance company, it naturally focused on when people who were considering purchasing insurance would die.

After extensively examining death records, he found that the risk of death increases exponentially each year starting in the late 20s.

The risk of death doubled approximately every seven years.

A 25-year-old has only a 0.1 percent chance of dying within the next year.

However, this figure jumps to 1 percent at age 60, 6 percent at age 80, and 16 percent at age 100.

A 108-year-old person has only a 50 percent chance of living another year.

--- p.54~55

The debate surrounding whether there is a limit to human lifespan has even given rise to a famous bet.

At a 2001 conference, a reporter asked Steven Ostad when he thought someone would live past 150.

Although the atmosphere was such that no one wanted to take a risk, Ostad spat out bluntly.

“I think it will come from people who are alive now.” Olshansky, who was still skeptical that lifespan could be extended beyond a certain point, read the article, called Ostad, and proposed a friendly wager.

Some might think it's a safe bet since both men are likely to die before the outcome is determined, but they took that into account.

They each agreed to put $150 into the fund for 150 years.

As Ostad points out, it's a bet with a nice symmetry.

Olshansky estimates that if $150 is deposited over 150 years, the winner or his or her descendants will receive $500 million.

--- p.69

Paradoxically, many of the new cancer treatments inhibit DNA repair pathways.

Cancer cells have defects in some of their repair mechanisms, so inhibiting other repair pathways can lead to their downfall.

Cancer cells that are unable to repair their own DNA die.

However, this is only a short-term solution for aggressive cancer. Long-term inhibition of DNA repair mechanisms not only increases the risk of cancer but also accelerates aging.

Because aging and cancer interact so subtly, strategies that leverage knowledge of DNA damage and repair to address aging are unlikely to succeed.

--- p.101

Cancer cells activate telomerase.

If we could inhibit or inactivate telomerase, wouldn't we be able to kill cancer cells? On the other hand, inactivating telomerase not only accelerates telomere shortening, leading to premature aging and disease, but it could also cause telomeres to break down, leading to chromosomal rearrangements, potentially leading to cancer.

It's a delicate balance between two opposing possibilities: telomere shortening and aging on one side, and increased cancer risk on the other.

Perhaps telomerase is inactive in most cells at an early age, preventing cancer.

--- p.116

Identical twins show that the notion that DNA equals destiny is wrong.

Identical twins have all the same genes, and even though they grow up apart at birth, they are surprisingly similar when they meet later in life.

That's natural.

What's truly remarkable is that even identical twins raised in the same environment can sometimes differ significantly, even for conditions with a strong genetic basis, such as schizophrenia.

--- p.125

Everyone knows a family that lives long.

How much, exactly, do genes influence longevity? A study of 2,700 twins in Denmark found that only 25 percent of longevity can be explained by genetics (quantifying genetic differences and comparing them to age at death).

Additionally, because genetic factors are thought to be the combined effect of many genes each having a very small influence, it is difficult to say exactly how much influence each gene has.

But in 1996, when the Danish study was conducted, a small bug had already turned that notion on its head.

--- p.208

One reason for the interest in metformin is that its long-term safety has been established in patients with diabetes.

If you suffer from diabetes, you may be happy to take it.

Because the risk of getting sick or dying from diabetes complications is much lower than if you don't get treatment.

However, considering the potential problems noted above, recommending long-term metformin use in healthy adults is a completely different matter.

--- p.226

Although there have been sporadic reports that antioxidants may be helpful, a recent analysis of 68 randomized clinical trials of antioxidant supplements, involving a total of 230,000 participants, found that not only did these substances not reduce mortality, but some antioxidants, such as beta-carotene, vitamin A, and vitamin E, actually increased mortality.

This opinion itself does not mean that the free radical theory is of no help.

The real point is that simply popping a few antioxidant supplement pills won't significantly prevent free radical damage.

Still, there's no need to give up kale.

--- p.254

He demonstrated that blood from older animals can impair the memory of younger animals, and conversely, blood from younger animals can improve the memory of older animals.

Older mice had a threefold increase in the number of new neurons they generated, while younger mice that received blood transfusions from older animals through parabiosis produced significantly fewer neurons in their brains than controls.

--- p.276~277

Ettinger believed that future scientists would be able to revive frozen bodies, curing any illness and restoring youth.

In 1976, he founded the Cryonics Institute near Detroit and recruited over 100 applicants.

The applicants each agreed to pay $28,000 to have their bodies cryopreserved in large containers of liquid nitrogen.

Among the first people to enter the freezer was Ettinger's mother, Leah, who died in 1977.

Two women who were his wives are also currently cryopreserved there.

It is unclear how happy they were to be preserved side by side, and by their mother-in-law, for years or even decades.

Ettinger, who died in 2011 at the age of 92, also joined the family, following the tradition of staying close to them even after death.

--- p.286~287

When it comes to optimism, David Sinclair is a must-have.

Unlike other frauds in this field, he is a Harvard professor who has published several notable papers on aging in prestigious journals.

Two recent papers on cellular reprogramming have generated considerable buzz.

At the same time, Sinclair is also known for his excessive self-promotion and enthusiastic claims.

For example, he has argued that one day, a time will come when you can go to a doctor and get a prescription for a drug that will make you 10 years younger, and that there is no reason why humans cannot live to be 200 years old.

Naturally, critics frowned, and even fellow scientists who admired his abilities could not help but be taken aback.

--- p.297

This is especially true for California's high-tech tycoons.

They usually made their money in the software industry.

Because we have the ability to create programs that can perform financial transactions or exchange various information in an instant, we believe that aging is just another engineering problem that can be solved by hacking the code of life.

Because I have experienced a sudden fortune, I am impatient.

We underestimate the complexity of the problem of aging because we are accustomed to making huge innovations in a year, or even a month or two.

What they want is to “move quickly and destroy the existing order.”

...

These are the very people who are throwing AI into the world for which it is not even properly prepared, while at the same time warning of its dangers.

And to see that attitude applied to the profound field of aging and life extension is simply frightening.

--- p.302~303

Mr. Moore's words cut to the heart of intergenerational fairness.

The oldest professor usually receives a very high salary, which allows him to hire two young scientists who consistently do good research.

Even if they don't receive a salary, they continue to take up valuable resources, such as lab space, that young professors need.

Who knows, if a young professor is appointed to that position, he or she might one day bring about a groundbreaking innovation, opening up a completely new field? Furthermore, older researchers influence the agenda of their institutions and the scientific community as a whole, but they tend to be conservative and incremental rather than innovative and bold.

The situation is similar in other fields, such as corporations.

The issue of intergenerational fairness clashes with the pressure to continue working into later ages as the population ages.

What should I do?

--- p.16~17

Why on earth does death exist? Why can't we just live forever?

The 20th-century Russian geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky wrote:

“If you don’t look at biology through the lens of evolution, none of it makes sense.” In biology, whenever the question “why does something happen?” is asked, the ultimate answer is always “because it evolved that way.”

When I first thought about the question, 'Why do we die?', I naively thought this:

Perhaps death is nature's way of ensuring the survival of genes, preventing old individuals from needlessly surviving and competing for resources so that new generations can thrive and procreate. Furthermore, each individual in the new generation possesses a different genetic combination than its parents.

Could it be that by constantly shuffling the cards of life, we help the survival of the entire species?

This idea has been around at least since the time of the Roman poet Lucretius, who lived in the first century BC.

It has that much appeal.

But I was wrong.

--- p.32~33

In 1825, Benjamin Gompertz, a self-taught British mathematician, studied the relationship between mortality and age.

Since the study was commissioned by an insurance company, it naturally focused on when people who were considering purchasing insurance would die.

After extensively examining death records, he found that the risk of death increases exponentially each year starting in the late 20s.

The risk of death doubled approximately every seven years.

A 25-year-old has only a 0.1 percent chance of dying within the next year.

However, this figure jumps to 1 percent at age 60, 6 percent at age 80, and 16 percent at age 100.

A 108-year-old person has only a 50 percent chance of living another year.

--- p.54~55

The debate surrounding whether there is a limit to human lifespan has even given rise to a famous bet.

At a 2001 conference, a reporter asked Steven Ostad when he thought someone would live past 150.

Although the atmosphere was such that no one wanted to take a risk, Ostad spat out bluntly.

“I think it will come from people who are alive now.” Olshansky, who was still skeptical that lifespan could be extended beyond a certain point, read the article, called Ostad, and proposed a friendly wager.

Some might think it's a safe bet since both men are likely to die before the outcome is determined, but they took that into account.

They each agreed to put $150 into the fund for 150 years.

As Ostad points out, it's a bet with a nice symmetry.

Olshansky estimates that if $150 is deposited over 150 years, the winner or his or her descendants will receive $500 million.

--- p.69

Paradoxically, many of the new cancer treatments inhibit DNA repair pathways.

Cancer cells have defects in some of their repair mechanisms, so inhibiting other repair pathways can lead to their downfall.

Cancer cells that are unable to repair their own DNA die.

However, this is only a short-term solution for aggressive cancer. Long-term inhibition of DNA repair mechanisms not only increases the risk of cancer but also accelerates aging.

Because aging and cancer interact so subtly, strategies that leverage knowledge of DNA damage and repair to address aging are unlikely to succeed.

--- p.101

Cancer cells activate telomerase.

If we could inhibit or inactivate telomerase, wouldn't we be able to kill cancer cells? On the other hand, inactivating telomerase not only accelerates telomere shortening, leading to premature aging and disease, but it could also cause telomeres to break down, leading to chromosomal rearrangements, potentially leading to cancer.

It's a delicate balance between two opposing possibilities: telomere shortening and aging on one side, and increased cancer risk on the other.

Perhaps telomerase is inactive in most cells at an early age, preventing cancer.

--- p.116

Identical twins show that the notion that DNA equals destiny is wrong.

Identical twins have all the same genes, and even though they grow up apart at birth, they are surprisingly similar when they meet later in life.

That's natural.

What's truly remarkable is that even identical twins raised in the same environment can sometimes differ significantly, even for conditions with a strong genetic basis, such as schizophrenia.

--- p.125

Everyone knows a family that lives long.

How much, exactly, do genes influence longevity? A study of 2,700 twins in Denmark found that only 25 percent of longevity can be explained by genetics (quantifying genetic differences and comparing them to age at death).

Additionally, because genetic factors are thought to be the combined effect of many genes each having a very small influence, it is difficult to say exactly how much influence each gene has.

But in 1996, when the Danish study was conducted, a small bug had already turned that notion on its head.

--- p.208

One reason for the interest in metformin is that its long-term safety has been established in patients with diabetes.

If you suffer from diabetes, you may be happy to take it.

Because the risk of getting sick or dying from diabetes complications is much lower than if you don't get treatment.

However, considering the potential problems noted above, recommending long-term metformin use in healthy adults is a completely different matter.

--- p.226

Although there have been sporadic reports that antioxidants may be helpful, a recent analysis of 68 randomized clinical trials of antioxidant supplements, involving a total of 230,000 participants, found that not only did these substances not reduce mortality, but some antioxidants, such as beta-carotene, vitamin A, and vitamin E, actually increased mortality.

This opinion itself does not mean that the free radical theory is of no help.

The real point is that simply popping a few antioxidant supplement pills won't significantly prevent free radical damage.

Still, there's no need to give up kale.

--- p.254

He demonstrated that blood from older animals can impair the memory of younger animals, and conversely, blood from younger animals can improve the memory of older animals.

Older mice had a threefold increase in the number of new neurons they generated, while younger mice that received blood transfusions from older animals through parabiosis produced significantly fewer neurons in their brains than controls.

--- p.276~277

Ettinger believed that future scientists would be able to revive frozen bodies, curing any illness and restoring youth.

In 1976, he founded the Cryonics Institute near Detroit and recruited over 100 applicants.

The applicants each agreed to pay $28,000 to have their bodies cryopreserved in large containers of liquid nitrogen.

Among the first people to enter the freezer was Ettinger's mother, Leah, who died in 1977.

Two women who were his wives are also currently cryopreserved there.

It is unclear how happy they were to be preserved side by side, and by their mother-in-law, for years or even decades.

Ettinger, who died in 2011 at the age of 92, also joined the family, following the tradition of staying close to them even after death.

--- p.286~287

When it comes to optimism, David Sinclair is a must-have.

Unlike other frauds in this field, he is a Harvard professor who has published several notable papers on aging in prestigious journals.

Two recent papers on cellular reprogramming have generated considerable buzz.

At the same time, Sinclair is also known for his excessive self-promotion and enthusiastic claims.

For example, he has argued that one day, a time will come when you can go to a doctor and get a prescription for a drug that will make you 10 years younger, and that there is no reason why humans cannot live to be 200 years old.

Naturally, critics frowned, and even fellow scientists who admired his abilities could not help but be taken aback.

--- p.297

This is especially true for California's high-tech tycoons.

They usually made their money in the software industry.

Because we have the ability to create programs that can perform financial transactions or exchange various information in an instant, we believe that aging is just another engineering problem that can be solved by hacking the code of life.

Because I have experienced a sudden fortune, I am impatient.

We underestimate the complexity of the problem of aging because we are accustomed to making huge innovations in a year, or even a month or two.

What they want is to “move quickly and destroy the existing order.”

...

These are the very people who are throwing AI into the world for which it is not even properly prepared, while at the same time warning of its dangers.

And to see that attitude applied to the profound field of aging and life extension is simply frightening.

--- p.302~303

Mr. Moore's words cut to the heart of intergenerational fairness.

The oldest professor usually receives a very high salary, which allows him to hire two young scientists who consistently do good research.

Even if they don't receive a salary, they continue to take up valuable resources, such as lab space, that young professors need.

Who knows, if a young professor is appointed to that position, he or she might one day bring about a groundbreaking innovation, opening up a completely new field? Furthermore, older researchers influence the agenda of their institutions and the scientific community as a whole, but they tend to be conservative and incremental rather than innovative and bold.

The situation is similar in other fields, such as corporations.

The issue of intergenerational fairness clashes with the pressure to continue working into later ages as the population ages.

What should I do?

--- p.335

Publisher's Review

Nobel Prize-winning molecular biologist Venky Ramakrishnan tells us

The Science of Aging, Longevity, Death, and the Pursuit of Immortality

What is death? Why on earth are we destined to grow old and die?

The era of a biological revolution that is shifting the paradigm of aging science.

Beyond the fervent anticipation and rosy hopes, death and life are portrayed with a deep and balanced perspective.

“This field is developing at a tremendous pace, with huge amounts of public and private investment, resulting in a huge bubble.

“Now is the time for someone like me, someone in the field of molecular biology with no direct stake in it, to come forward and explain honestly and objectively what we currently know about aging and death.” (p. 18)

There is a growing global interest in the science of life extension and the anti-aging industry.

“Over the past decade, more than 300,000 scientific papers have been published on aging.

There are over 700 startups addressing aging issues, with combined investment reaching hundreds of billions of dollars.

“This number does not include the programs currently being implemented by existing large pharmaceutical companies.” (Page 16) The situation in Korea, which is on the verge of entering a super-aged society with an increase in average life expectancy and a sharp decline in birth rate, is no different.

Books, videos, anti-aging supplements, and dietary supplements that teach people how to stay young and live a long, healthy life are gaining popularity.

When I hear news of advancements in biology and medicine, it seems like we are right in the middle of an era where everyone will enjoy a healthy old age and live to be 100.

"Why We Die" is a book that presents at a glance the significant facts that biology has revealed about aging and death.

The author, Venky Ramakrishnan, is a British molecular biologist who has been elucidating the workings of life through his research on ribosomes, which can be called the protein production factories of our bodies, and was awarded the 2009 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

He also served as President of the Royal Society from 2015 to 2020.

As someone who is more knowledgeable about molecular biology than anyone else, he explains in an entertaining way what happens at the genetic, protein, and cellular levels to cause aging.

It calmly examines what efforts are being made to slow and even reverse aging, and what challenges remain, with critical comments on several star scientists and prominent biotech companies.

Furthermore, it elegantly unfolds a story filled with extraordinary insight, examining whether death has a biologically necessary purpose, the various social problems that life extension will bring, and the ethical price of trying to live forever.

Beyond the fervent expectations and rosy hopes of extending healthy lifespan, it allows us to look at aging and death with new eyes.

Why on earth are we destined to die?

Except for deaths caused by accidents, war, epidemics, environmental disasters, etc., death is generally a result of aging.

Simply put, aging is the accumulation of chemical damage to the body's molecules and cells. This damage causes small defects in the body to accumulate, leading to the diseases of old age, and eventually, when the entire system ceases to function, the organism faces death (p. 25).

Of course, even if an individual dies, its genes do not die and are passed on to future generations.

So why didn't evolution prevent aging in the first place? If we lived longer and left behind more offspring, we'd have more opportunities to leave behind more offspring.

Chapter 1 explores these questions and introduces various theories about death, including Peter Medawar's "mutation accumulation theory of aging," the "antagonistic pleiotropy" theory that suggests that genes that are beneficial to an organism early in life can have detrimental effects in old age, and Thomas Kirkwood's "disposable body hypothesis."

What makes these incredibly long-lived creatures different?

Chapter 2 explains the surprising facts we learn about lifespan when we broaden our perspective to creatures other than humans.

One of the apple trees in the Cambridge University Botanic Gardens was regrown from a cutting taken from the tree that once stood at the house where Isaac Newton lived.

Thanks to this amazing regenerative ability, some species of trees can live for thousands of years.

The small aquatic animal Hydra can also regenerate tissues continuously, making it appear as if it never ages, and the red jellyfish, also known as the "immortal jellyfish," undergoes metamorphosis and reverts to an earlier stage of development when exposed to a stressful environment.

Among vertebrates, the bowhead whale is known to live for 200 years, and the Greenland shark for 400 years.

Also on the list are the naked mole rat, a mascot of the aging research community with its strong resistance to cancer, and the greater bearded bat, which has the highest lifespan quotient (LQ) of all mammals.

According to the general law of animal size, metabolic rate, and lifespan presented by the Santa Fe Institute, it is known that the lifespan of animals is generally proportional to the size of their bodies, and it is also interesting that the average lifespan of humans is five times longer than the lifespan expected according to this standard (p. 52).

The book explores the question of whether there are biological limits to human lifespan by introducing record-breaking centenarians, including Jeanne Calment, the woman who died at age 122 and is now the oldest living person ever recorded, and what makes centenarians so special.

An exciting adventure to the frontiers of biology

Fluent sentences, excellent metaphors, and a model of rigorous yet popular science writing.

Chapters 3 through 10 detail the biological mechanisms of aging at various levels, from genes to proteins, and introduce important advances that have dramatically expanded our understanding of aging and death.

First, in Chapter 3, which introduces various cases of DNA damage and the mechanisms for repairing it, you will encounter biological processes such as 'excision repair' and 'apoptosis', as well as tumor suppressor genes and DNA repair genes.

Chapter 4 is a dynamic story about how the length of the telomeres at the ends of chromosomes shortens each time they divide, and when these shorten below a certain length, the cell eventually stops dividing and enters senescence (Hayflick limit), and the discovery of the telomere repair enzyme (telomerase).

Chapter 5 examines epigenetic changes that occur as a result of our life history and environmental influences, and explores the possibility of turning back the aging clock in our bodies. Chapter 6 explains why defective proteins are created in cells, what happens to correct them (autophagy, protein synthesis shutdown, etc.), and how this is related to age-related diseases such as Alzheimer's.

Chapter 7 explores the scientific research that shows why fasting is beneficial and tells the story of researchers' quest to find drugs that allow people to enjoy the benefits of calorie restriction while still being able to eat freely. Chapter 8 explores specific hormones that regulate aging, including a longevity gene discovered in the worm C. elegans.

We also examine substances such as metformin, resveratrol, NAD, and NMN, which were once highly anticipated sirtuins and are also receiving attention as anti-aging agents.

Chapter 9 takes a closer look at mitochondria, which are not only energy production factories but also the centers of cellular metabolism.

It covers the actual effects of antioxidants that prevent the effects of free radicals and their dangers, inflammation and aging, and it also explains that exercise is a panacea for mitochondrial dysfunction.

Chapter 10 explores how cellular aging causes age-related diseases.

We also take a serious look at the causes of inflammation, the possibilities and limitations of stem cell-based aging reversal, cellular reprogramming using Yamanaka factors, and the effects of young blood transfusions.

The book comprehensively covers the major mechanisms of aging, from basic knowledge about cells to DNA damage and repair, telomeres, epigenetics, calorie restriction, autophagy, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidation by free radicals, and inflammation.

To achieve this, the author combs through extensive research papers, reviews, and articles, and even speaks directly with leading scholars or conducts email interviews. This reflects the meticulous approach of a scholar engaged in rigorous scientific research.

Without glossing over the facts, it clearly distinguishes between what is known and what is not.

This allows readers to objectively understand the state of aging science and develop the ability to critically examine unproven drugs and treatments.

While covering a vast amount of material, it manages to summarize only the key points in an easy-to-understand format, and even difficult content is explained in the easiest-to-understand way possible through excellent analogies.

It is a very entertaining read, as it breathlessly unfolds the history of discovery, while also adding amusing anecdotes from researchers and the author's own personal assessments.

The occasional humor you find adds to the enjoyment of reading the book.

A unique strength of this book, one that is hard to find in other books, is that it examines the mechanisms of aging from a highly integrative perspective.

What the author constantly emphasizes is that despite the amazing achievements of aging science, there is still much that remains to be discovered.

Because each mechanism is closely linked at the molecular, genetic, protein, and cellular levels, what may seem like a breakthrough in one area may have negative consequences in another.

It is also noteworthy that the biological mechanisms that promote regeneration and recovery and those that cause cancer are repeatedly pointed out to be in conflict at every level of the body.

“While explaining how advances in molecular biology have shed light on all aspects of aging, he often takes a skeptical view of the hype,” he said. “Given the money and desperation currently being poured into aging research...

While he says, “Something may change significantly in just a few years,” he also shows a cautious stance, saying, “Aging is such a complex phenomenon that it is difficult to predict easily” (p. 342).

Is he a madman, a fraud, or a prophet?

Chapter 11, which covers current efforts to combat aging and death, will be particularly interesting for readers interested in anti-aging science.

Cryonics, the practice of freezing the bodies of those who have died from illness until a cure is found and then reviving them (celebrities like Peter Thiel, Ray Kurzweil, Nick Bostrom, and Sam Altman are known to want to be cryopreserved after death), is a technique commonly used in science fiction works such as The Three-Body Problem, but the author states bluntly, “There is absolutely no evidence to suggest that thawing the bodies of those who have died from illness in a state in which they would be indistinguishable from life” (p. 291).

The same goes for using the developing field of connectomics to map all the neurons in the brain and then later resurrect the brain.

The author puts Aubrey de Grey, who has been causing controversy since he proposed the concept of “escape velocity,” which means that “if life expectancy increases faster than the rate at which we age—in other words, if life expectancy increases by more than a year every year—we would escape death forever” (p. 294), on the chopping block. He also criticizes star scientists in the mainstream anti-aging industry, including Harvard University aging scientist Professor David Sinclair, who do not hesitate to make “ethically questionable and potentially dangerous” remarks, as well as wealthy Silicon Valley tycoons and life extension companies like Altos Labs.

The concept of "disease state compression"—minimizing the time spent in poor health due to age-related diseases and increasing healthy life expectancy—is appealing, but it also points out that the actual trend is far from this.

Commentary like this can be read as a display of responsibility as a public intellectual, and it will help readers avoid being fooled by the rhetoric of life extension companies that exploit the fear of death and be able to interpret news related to the aging industry more critically.

The philosophical, social, and ethical questions that life extension raises

"What would society look like if such technologies became widespread? Could we be sleepwalking into the future, ignoring the social, economic, and political consequences of living much longer than we do now? Given recent advances and the enormous investment in aging research, we must consider where this research might lead us and what choices it might offer regarding human limitations." (pp. 16-17)

Ultimately, while cautioning against excessive optimism, the author predicts that “after a winter of disillusionment and discontent, important advances will eventually be made in the science of aging” (p. 344).

Therefore, the book goes beyond explaining the biology of aging to consider what we need to consider before we reach a world where life expectancy has dramatically increased thanks to some successes in aging science.

Growing inequality, overpopulation, the need for longer retirement ages, declining creativity, and intergenerational fairness are all issues that our society must grapple with together.

It's also interesting to hear his honest, almost self-deprecating, opinion on the claim that age brings wisdom and creativity.

A love letter to our fleeting existence

While the author does not deny the deep-seated human instinct to live long and healthy lives (he himself admits to taking high blood pressure medication, high cholesterol medication, and low-dose aspirin to prevent blood clots every day), he points out that “we cannot be sure that living much longer will lead much more satisfying lives,” and that “it is much wiser to accept the finiteness of life” rather than chasing a mirage of life extension.

“It is precisely this finitude that provides the desire and self-encouragement to make the most of the time given on earth” (p. 339).

This is a position that many readers will likely agree with.

“Understanding why we must die helps us know how we should live.

As the recommendation by Chris Van Tooluken states, “While reading the book, my perspective on the entire living world, and above all, my perspective on myself and the time I have left, changed,” I hope that this book will become a tool for reflection that will allow the reader to look at the time of their lives in a new way.

The Science of Aging, Longevity, Death, and the Pursuit of Immortality

What is death? Why on earth are we destined to grow old and die?

The era of a biological revolution that is shifting the paradigm of aging science.

Beyond the fervent anticipation and rosy hopes, death and life are portrayed with a deep and balanced perspective.

“This field is developing at a tremendous pace, with huge amounts of public and private investment, resulting in a huge bubble.

“Now is the time for someone like me, someone in the field of molecular biology with no direct stake in it, to come forward and explain honestly and objectively what we currently know about aging and death.” (p. 18)

There is a growing global interest in the science of life extension and the anti-aging industry.

“Over the past decade, more than 300,000 scientific papers have been published on aging.

There are over 700 startups addressing aging issues, with combined investment reaching hundreds of billions of dollars.

“This number does not include the programs currently being implemented by existing large pharmaceutical companies.” (Page 16) The situation in Korea, which is on the verge of entering a super-aged society with an increase in average life expectancy and a sharp decline in birth rate, is no different.

Books, videos, anti-aging supplements, and dietary supplements that teach people how to stay young and live a long, healthy life are gaining popularity.

When I hear news of advancements in biology and medicine, it seems like we are right in the middle of an era where everyone will enjoy a healthy old age and live to be 100.

"Why We Die" is a book that presents at a glance the significant facts that biology has revealed about aging and death.

The author, Venky Ramakrishnan, is a British molecular biologist who has been elucidating the workings of life through his research on ribosomes, which can be called the protein production factories of our bodies, and was awarded the 2009 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

He also served as President of the Royal Society from 2015 to 2020.

As someone who is more knowledgeable about molecular biology than anyone else, he explains in an entertaining way what happens at the genetic, protein, and cellular levels to cause aging.

It calmly examines what efforts are being made to slow and even reverse aging, and what challenges remain, with critical comments on several star scientists and prominent biotech companies.

Furthermore, it elegantly unfolds a story filled with extraordinary insight, examining whether death has a biologically necessary purpose, the various social problems that life extension will bring, and the ethical price of trying to live forever.

Beyond the fervent expectations and rosy hopes of extending healthy lifespan, it allows us to look at aging and death with new eyes.

Why on earth are we destined to die?

Except for deaths caused by accidents, war, epidemics, environmental disasters, etc., death is generally a result of aging.

Simply put, aging is the accumulation of chemical damage to the body's molecules and cells. This damage causes small defects in the body to accumulate, leading to the diseases of old age, and eventually, when the entire system ceases to function, the organism faces death (p. 25).

Of course, even if an individual dies, its genes do not die and are passed on to future generations.

So why didn't evolution prevent aging in the first place? If we lived longer and left behind more offspring, we'd have more opportunities to leave behind more offspring.

Chapter 1 explores these questions and introduces various theories about death, including Peter Medawar's "mutation accumulation theory of aging," the "antagonistic pleiotropy" theory that suggests that genes that are beneficial to an organism early in life can have detrimental effects in old age, and Thomas Kirkwood's "disposable body hypothesis."

What makes these incredibly long-lived creatures different?

Chapter 2 explains the surprising facts we learn about lifespan when we broaden our perspective to creatures other than humans.

One of the apple trees in the Cambridge University Botanic Gardens was regrown from a cutting taken from the tree that once stood at the house where Isaac Newton lived.

Thanks to this amazing regenerative ability, some species of trees can live for thousands of years.

The small aquatic animal Hydra can also regenerate tissues continuously, making it appear as if it never ages, and the red jellyfish, also known as the "immortal jellyfish," undergoes metamorphosis and reverts to an earlier stage of development when exposed to a stressful environment.

Among vertebrates, the bowhead whale is known to live for 200 years, and the Greenland shark for 400 years.

Also on the list are the naked mole rat, a mascot of the aging research community with its strong resistance to cancer, and the greater bearded bat, which has the highest lifespan quotient (LQ) of all mammals.

According to the general law of animal size, metabolic rate, and lifespan presented by the Santa Fe Institute, it is known that the lifespan of animals is generally proportional to the size of their bodies, and it is also interesting that the average lifespan of humans is five times longer than the lifespan expected according to this standard (p. 52).

The book explores the question of whether there are biological limits to human lifespan by introducing record-breaking centenarians, including Jeanne Calment, the woman who died at age 122 and is now the oldest living person ever recorded, and what makes centenarians so special.

An exciting adventure to the frontiers of biology

Fluent sentences, excellent metaphors, and a model of rigorous yet popular science writing.

Chapters 3 through 10 detail the biological mechanisms of aging at various levels, from genes to proteins, and introduce important advances that have dramatically expanded our understanding of aging and death.

First, in Chapter 3, which introduces various cases of DNA damage and the mechanisms for repairing it, you will encounter biological processes such as 'excision repair' and 'apoptosis', as well as tumor suppressor genes and DNA repair genes.

Chapter 4 is a dynamic story about how the length of the telomeres at the ends of chromosomes shortens each time they divide, and when these shorten below a certain length, the cell eventually stops dividing and enters senescence (Hayflick limit), and the discovery of the telomere repair enzyme (telomerase).

Chapter 5 examines epigenetic changes that occur as a result of our life history and environmental influences, and explores the possibility of turning back the aging clock in our bodies. Chapter 6 explains why defective proteins are created in cells, what happens to correct them (autophagy, protein synthesis shutdown, etc.), and how this is related to age-related diseases such as Alzheimer's.

Chapter 7 explores the scientific research that shows why fasting is beneficial and tells the story of researchers' quest to find drugs that allow people to enjoy the benefits of calorie restriction while still being able to eat freely. Chapter 8 explores specific hormones that regulate aging, including a longevity gene discovered in the worm C. elegans.

We also examine substances such as metformin, resveratrol, NAD, and NMN, which were once highly anticipated sirtuins and are also receiving attention as anti-aging agents.

Chapter 9 takes a closer look at mitochondria, which are not only energy production factories but also the centers of cellular metabolism.

It covers the actual effects of antioxidants that prevent the effects of free radicals and their dangers, inflammation and aging, and it also explains that exercise is a panacea for mitochondrial dysfunction.

Chapter 10 explores how cellular aging causes age-related diseases.

We also take a serious look at the causes of inflammation, the possibilities and limitations of stem cell-based aging reversal, cellular reprogramming using Yamanaka factors, and the effects of young blood transfusions.

The book comprehensively covers the major mechanisms of aging, from basic knowledge about cells to DNA damage and repair, telomeres, epigenetics, calorie restriction, autophagy, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidation by free radicals, and inflammation.

To achieve this, the author combs through extensive research papers, reviews, and articles, and even speaks directly with leading scholars or conducts email interviews. This reflects the meticulous approach of a scholar engaged in rigorous scientific research.

Without glossing over the facts, it clearly distinguishes between what is known and what is not.

This allows readers to objectively understand the state of aging science and develop the ability to critically examine unproven drugs and treatments.

While covering a vast amount of material, it manages to summarize only the key points in an easy-to-understand format, and even difficult content is explained in the easiest-to-understand way possible through excellent analogies.

It is a very entertaining read, as it breathlessly unfolds the history of discovery, while also adding amusing anecdotes from researchers and the author's own personal assessments.

The occasional humor you find adds to the enjoyment of reading the book.

A unique strength of this book, one that is hard to find in other books, is that it examines the mechanisms of aging from a highly integrative perspective.

What the author constantly emphasizes is that despite the amazing achievements of aging science, there is still much that remains to be discovered.

Because each mechanism is closely linked at the molecular, genetic, protein, and cellular levels, what may seem like a breakthrough in one area may have negative consequences in another.

It is also noteworthy that the biological mechanisms that promote regeneration and recovery and those that cause cancer are repeatedly pointed out to be in conflict at every level of the body.

“While explaining how advances in molecular biology have shed light on all aspects of aging, he often takes a skeptical view of the hype,” he said. “Given the money and desperation currently being poured into aging research...

While he says, “Something may change significantly in just a few years,” he also shows a cautious stance, saying, “Aging is such a complex phenomenon that it is difficult to predict easily” (p. 342).

Is he a madman, a fraud, or a prophet?

Chapter 11, which covers current efforts to combat aging and death, will be particularly interesting for readers interested in anti-aging science.

Cryonics, the practice of freezing the bodies of those who have died from illness until a cure is found and then reviving them (celebrities like Peter Thiel, Ray Kurzweil, Nick Bostrom, and Sam Altman are known to want to be cryopreserved after death), is a technique commonly used in science fiction works such as The Three-Body Problem, but the author states bluntly, “There is absolutely no evidence to suggest that thawing the bodies of those who have died from illness in a state in which they would be indistinguishable from life” (p. 291).

The same goes for using the developing field of connectomics to map all the neurons in the brain and then later resurrect the brain.

The author puts Aubrey de Grey, who has been causing controversy since he proposed the concept of “escape velocity,” which means that “if life expectancy increases faster than the rate at which we age—in other words, if life expectancy increases by more than a year every year—we would escape death forever” (p. 294), on the chopping block. He also criticizes star scientists in the mainstream anti-aging industry, including Harvard University aging scientist Professor David Sinclair, who do not hesitate to make “ethically questionable and potentially dangerous” remarks, as well as wealthy Silicon Valley tycoons and life extension companies like Altos Labs.

The concept of "disease state compression"—minimizing the time spent in poor health due to age-related diseases and increasing healthy life expectancy—is appealing, but it also points out that the actual trend is far from this.

Commentary like this can be read as a display of responsibility as a public intellectual, and it will help readers avoid being fooled by the rhetoric of life extension companies that exploit the fear of death and be able to interpret news related to the aging industry more critically.

The philosophical, social, and ethical questions that life extension raises

"What would society look like if such technologies became widespread? Could we be sleepwalking into the future, ignoring the social, economic, and political consequences of living much longer than we do now? Given recent advances and the enormous investment in aging research, we must consider where this research might lead us and what choices it might offer regarding human limitations." (pp. 16-17)

Ultimately, while cautioning against excessive optimism, the author predicts that “after a winter of disillusionment and discontent, important advances will eventually be made in the science of aging” (p. 344).

Therefore, the book goes beyond explaining the biology of aging to consider what we need to consider before we reach a world where life expectancy has dramatically increased thanks to some successes in aging science.

Growing inequality, overpopulation, the need for longer retirement ages, declining creativity, and intergenerational fairness are all issues that our society must grapple with together.

It's also interesting to hear his honest, almost self-deprecating, opinion on the claim that age brings wisdom and creativity.

A love letter to our fleeting existence

While the author does not deny the deep-seated human instinct to live long and healthy lives (he himself admits to taking high blood pressure medication, high cholesterol medication, and low-dose aspirin to prevent blood clots every day), he points out that “we cannot be sure that living much longer will lead much more satisfying lives,” and that “it is much wiser to accept the finiteness of life” rather than chasing a mirage of life extension.

“It is precisely this finitude that provides the desire and self-encouragement to make the most of the time given on earth” (p. 339).

This is a position that many readers will likely agree with.

“Understanding why we must die helps us know how we should live.

As the recommendation by Chris Van Tooluken states, “While reading the book, my perspective on the entire living world, and above all, my perspective on myself and the time I have left, changed,” I hope that this book will become a tool for reflection that will allow the reader to look at the time of their lives in a new way.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: May 30, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 432 pages | 594g | 145*215*25mm

- ISBN13: 9788934942740

- ISBN10: 8934942746

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)