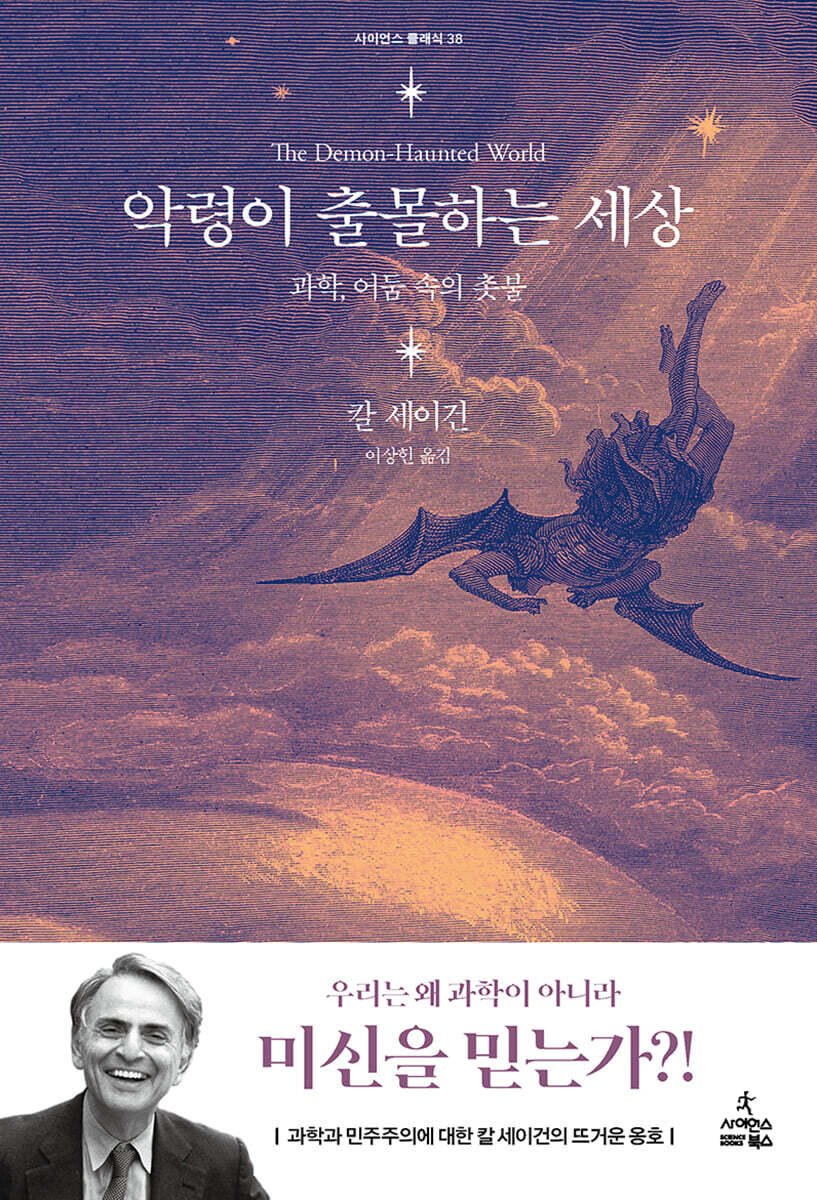

A world haunted by evil spirits

|

Description

Book Introduction

Why do we believe in superstition rather than science?

Carl Sagan's passionate defense of science and democracy

Witches and aliens, Taoists and wizards appear

An era of rampant anti-science, superstition, irrationalism, and anti-intellectualism

The Flickering Candle: Carl Sagan's Final Reflections on Science

Carl Sagan's final work, a completely revised edition

New York Times bestseller

Winner of the Los Angeles Times Science and Technology Book Award

Published to commemorate the 2022 International Year of Basic Science!

In May 2022, the U.S. Congress held a hearing on unidentified flying objects (UFOs), the first in over 50 years.

The hearing, which was attended by the Under Secretary of Defense and the Deputy Director of Naval Intelligence, discussed unidentified aerial phenomena (UAP) discovered by the U.S. military.

The US military has reported 400 sightings of what it calls "UFOs" (a term used by US military authorities instead of UFOs) since 2004.

However, it was also reported that no material evidence was obtained to suggest that these phenomena originated from somewhere other than Earth, that is, from extraterrestrial sources.

Experts point out that the surge in UAP or UFO sightings is linked to the commercialization of drones.

However, according to a Gallup poll conducted in June 2021, 41 percent of American adults believe UFOs are spaceships flown by aliens.

(This figure is an 8 percentage point increase from a survey conducted in August 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic.) See https://news.gallup.com/poll/353420/larger-minority-says-ufos-alien-spacecraft.aspx.

Among Americans who actually believe that alien abductions are occurring, there are quite a few who believe that more than 100 million people on Earth have been abducted by aliens and that alien abductions are still occurring around the world.

Even amid the recent COVID-19 pandemic, a significant number of Americans refused to get vaccinated, believing that the virus outbreak was a conspiracy by certain capitalists or powerful figures like Bill Gates, and that vaccines contained special substances designed to manipulate the minds of those vaccinated.

In Korea, there was an incident where some explanations of evolution were deleted from biology textbooks due to complaints from creationist groups, and pseudoscience promoting natural healing, such as the "raising children without drugs" movement, became popular.

Why do we believe in pseudoscience, superstition, and anti-intellectualism instead of science? Why do baseless and ineffective claims and myths persist and resurface? During the Western Middle Ages, also known as the Dark Ages, ancient demons were resurrected as witches. In modern times, these demons have transformed into aliens, haunting the shadows beyond the reach of scientific light.

Carl Edward Sagan, a representative 20th-century American planetary scientist and science evangelist, meticulously and deeply reflects on this pseudo-scientific fad born from ignorance of science and the absence of a spirit of skepticism, from its origins and history to its current state and alternatives, in his last book published before his death, The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark (1995).

This book, the product of ten years of research, reflection, study, and practice, passionately demonstrates that we cannot stop this trend of credulity without understanding the long-standing human desires behind the fads of anti-science, superstition, irrationalism, and anti-intellectualism, and without properly understanding the essence of science, which is born from the union of a skeptical mind and a sense of wonder.

Carl Sagan, who understood better than anyone that science had become more powerful than ever before, as symbolized by the atomic bomb, and that scientists were simultaneously given a correspondingly heavy responsibility, emphasized that it was scientists, not anyone else, who should step forward to protect people, society, and civilization from the flood of pseudoscience.

If scientists do not step forward, education levels decline, intellectual capacity weakens, people seek meaningful debate less, and the world ceases to recognize the value of skepticism, I fear that not only scientific progress but also societal and individual freedoms will gradually be eroded and, one day, deeply eroded.

If the candle of science flickers and then goes out weakly, the pyre of the witch hunt that burned lonely old women and innocent young women at the stake may be rekindled.

In his final moments, even as he suffered from myeloid leukemia, Sagan may have felt that his final mission was to properly inform people about the meaning, value, essence, and methods of science, which he had loved all his life.

Readers will find in this book his passionate advocacy and love for science and democracy.

Carl Sagan's passionate defense of science and democracy

Witches and aliens, Taoists and wizards appear

An era of rampant anti-science, superstition, irrationalism, and anti-intellectualism

The Flickering Candle: Carl Sagan's Final Reflections on Science

Carl Sagan's final work, a completely revised edition

New York Times bestseller

Winner of the Los Angeles Times Science and Technology Book Award

Published to commemorate the 2022 International Year of Basic Science!

In May 2022, the U.S. Congress held a hearing on unidentified flying objects (UFOs), the first in over 50 years.

The hearing, which was attended by the Under Secretary of Defense and the Deputy Director of Naval Intelligence, discussed unidentified aerial phenomena (UAP) discovered by the U.S. military.

The US military has reported 400 sightings of what it calls "UFOs" (a term used by US military authorities instead of UFOs) since 2004.

However, it was also reported that no material evidence was obtained to suggest that these phenomena originated from somewhere other than Earth, that is, from extraterrestrial sources.

Experts point out that the surge in UAP or UFO sightings is linked to the commercialization of drones.

However, according to a Gallup poll conducted in June 2021, 41 percent of American adults believe UFOs are spaceships flown by aliens.

(This figure is an 8 percentage point increase from a survey conducted in August 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic.) See https://news.gallup.com/poll/353420/larger-minority-says-ufos-alien-spacecraft.aspx.

Among Americans who actually believe that alien abductions are occurring, there are quite a few who believe that more than 100 million people on Earth have been abducted by aliens and that alien abductions are still occurring around the world.

Even amid the recent COVID-19 pandemic, a significant number of Americans refused to get vaccinated, believing that the virus outbreak was a conspiracy by certain capitalists or powerful figures like Bill Gates, and that vaccines contained special substances designed to manipulate the minds of those vaccinated.

In Korea, there was an incident where some explanations of evolution were deleted from biology textbooks due to complaints from creationist groups, and pseudoscience promoting natural healing, such as the "raising children without drugs" movement, became popular.

Why do we believe in pseudoscience, superstition, and anti-intellectualism instead of science? Why do baseless and ineffective claims and myths persist and resurface? During the Western Middle Ages, also known as the Dark Ages, ancient demons were resurrected as witches. In modern times, these demons have transformed into aliens, haunting the shadows beyond the reach of scientific light.

Carl Edward Sagan, a representative 20th-century American planetary scientist and science evangelist, meticulously and deeply reflects on this pseudo-scientific fad born from ignorance of science and the absence of a spirit of skepticism, from its origins and history to its current state and alternatives, in his last book published before his death, The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark (1995).

This book, the product of ten years of research, reflection, study, and practice, passionately demonstrates that we cannot stop this trend of credulity without understanding the long-standing human desires behind the fads of anti-science, superstition, irrationalism, and anti-intellectualism, and without properly understanding the essence of science, which is born from the union of a skeptical mind and a sense of wonder.

Carl Sagan, who understood better than anyone that science had become more powerful than ever before, as symbolized by the atomic bomb, and that scientists were simultaneously given a correspondingly heavy responsibility, emphasized that it was scientists, not anyone else, who should step forward to protect people, society, and civilization from the flood of pseudoscience.

If scientists do not step forward, education levels decline, intellectual capacity weakens, people seek meaningful debate less, and the world ceases to recognize the value of skepticism, I fear that not only scientific progress but also societal and individual freedoms will gradually be eroded and, one day, deeply eroded.

If the candle of science flickers and then goes out weakly, the pyre of the witch hunt that burned lonely old women and innocent young women at the stake may be rekindled.

In his final moments, even as he suffered from myeloid leukemia, Sagan may have felt that his final mission was to properly inform people about the meaning, value, essence, and methods of science, which he had loved all his life.

Readers will find in this book his passionate advocacy and love for science and democracy.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Beginning the Book: My Teachers … 9

Chapter 1: The Most Precious Thing… 19

Chapter 2: Science and Hope… 51

Chapter 3: Man on the Moon, Face on Mars… 77

Chapter 4: Aliens… 105

Chapter 5: Deception or Secrecy? … 131

Chapter 6: Hallucinations… 155

Chapter 7: A World Haunted by Demons… 177

Chapter 8: Is What You See Real or Fake? ... 209

Chapter 9 Treatment … 229

Chapter 10: The Dragon in the Garage… 255

Chapter 11: The City of Sorrow… 283

Chapter 12: Bullshit Detector … 299

Chapter 13: The Mask of Truth… 327

Chapter 14: Anti-Science … 365

Chapter 15: Newton's Sleep… 395

Chapter 16: When Scientists Know Sin… 417

Chapter 17: The Spirit of Doubt and the Sense of Wonder… 433

Chapter 18: What causes dust to rise… 453

Chapter 19: No Useless Questions… 469

Chapter 20: In a Burning House… 497

Chapter 21: The Road to Freedom… 519

Chapter 22: Slaves of Meaning… 539

Chapter 23: Maxwell and the Nerds… 557

Chapter 24: Science and the Witch Hunt… 589

Chapter 25: A True Patriot Raises Questions… 617

Acknowledgments … 636

References … 640

Search … 650

Chapter 1: The Most Precious Thing… 19

Chapter 2: Science and Hope… 51

Chapter 3: Man on the Moon, Face on Mars… 77

Chapter 4: Aliens… 105

Chapter 5: Deception or Secrecy? … 131

Chapter 6: Hallucinations… 155

Chapter 7: A World Haunted by Demons… 177

Chapter 8: Is What You See Real or Fake? ... 209

Chapter 9 Treatment … 229

Chapter 10: The Dragon in the Garage… 255

Chapter 11: The City of Sorrow… 283

Chapter 12: Bullshit Detector … 299

Chapter 13: The Mask of Truth… 327

Chapter 14: Anti-Science … 365

Chapter 15: Newton's Sleep… 395

Chapter 16: When Scientists Know Sin… 417

Chapter 17: The Spirit of Doubt and the Sense of Wonder… 433

Chapter 18: What causes dust to rise… 453

Chapter 19: No Useless Questions… 469

Chapter 20: In a Burning House… 497

Chapter 21: The Road to Freedom… 519

Chapter 22: Slaves of Meaning… 539

Chapter 23: Maxwell and the Nerds… 557

Chapter 24: Science and the Witch Hunt… 589

Chapter 25: A True Patriot Raises Questions… 617

Acknowledgments … 636

References … 640

Search … 650

Detailed image

.jpg)

Into the book

I am particularly concerned that, as we near the end of the last millennium, pseudoscience and superstition seem to be becoming more and more attractive with each passing year, and the maddening song of the fairy siren is becoming louder and more alluring.

Where have we heard that sound before? When prejudice against a people or nation gains ground, when famines run rampant, when national prestige and the very foundations of a nation are challenged, when we agonize over our place and purpose in the universe, or when fanaticism bubbles up around us, then those old, familiar habits of thought reach out to dominate us.

The candlelight gradually fades.

A small pool of sparks trembles.

Darkness gathers.

The evil spirits begin to stir.

Science cannot be said to be a perfect tool for pursuing knowledge.

Science is simply the best tool we have.

From this perspective, science is similar to democracy.

Science itself does not teach or advocate what human behavior should be.

But we can be sure that certain actions will lead to certain consequences.

However satisfying and reassuring it may be, I believe it is far better to understand the universe as it really is than to insist on delusion.

Pseudoscience is the exact opposite.

The hypotheses of pseudoscience are designed so that they cannot be falsified by any experiment.

It is even impossible to disprove in principle.

Adherents of pseudoscience are defensive and vigilant.

When you try to review it skeptically, it suddenly appears and interferes.

And when pseudoscientific hypotheses fail to gain scientific support, they conspire to somehow get around it.

For example, they claim that scientists are conspiring to suppress it.

Humans have been patiently and collectively investigating nature for centuries, distilling the results.

Of course, it might be easier to introduce already accomplished wisdom in a flashy way than to explain in detail this distillation process, which is riddled with all sorts of things.

Moreover, the scientific method seems like a cumbersome thing to deal with.

But this method is far more valuable than the discovery itself.

Another reason science has been successful is that error correction mechanisms are built into its core.

Some might criticize this as over-categorization, since correcting errors isn't unique to science, but I think every time we self-criticize, every time we apply our ideas to the outside world and test them, we are doing science.

When we are generous and uncritical of ourselves, when we confuse hope with fact, we slide into pseudoscience and superstition.

One of the great commandments of science is: 'Never believe arguments that appeal to authority.'

(Of course, scientists are also primates and are weak in group hierarchy, so they cannot always follow this commandment.)

Science is not only compatible with spirituality, but is also its profound source.

The feeling that arises when we recognize our place in the vast expanse of space and time, measured in light-years, or when we grasp the complexity, beauty, and subtlety of life—a feeling of elation combined with humility—is certainly mental or spiritual.

These efforts will continue as long as scientists exist.

General relativity is inadequate to describe nature at the quantum level.

But even if that were not the case, that is, even if general relativity were a valid theory at all times and everywhere, what better way to make it certain than by a concerted effort to discover its weaknesses and limitations?

This is one of the reasons why I am not very firm about organized religion.

What religious leader in the world would admit that their faith is imperfect or possibly wrong, and thus establish a research institute to uncover hidden weaknesses in their doctrines? Who would systematically research, beyond the testing of everyday life, to identify situations in which traditional religious teachings might no longer apply?

When skepticism is applied to world affairs, there is a tendency to trivialize problems, treat them as if they were superior, or ignore them.

But whether they're being deceived or not, proponents of superstition and pseudoscience are just as human as skeptics, with feelings and a desire to understand how the world works and what our role is in it.

Skeptics may be reluctant to admit it, but they often start from much the same motivations as scientists.

However, it may be that they simply did not receive the tools necessary for that exploration from their culture.

If that's true, wouldn't it be better to criticize more gently? After all, no one is born fully armed.

Unverifiable claims, unfalsifiable assertions, no matter how inspiring or awe-inspiring they may be, are worthless when it comes to truth.

What I'm saying is like asking you to believe it without any evidence.

If alien abduction stories are the result of brain physiology, hallucinations, distorted childhood memories, or fabrications, we face a very important problem.

This issue concerns the limitations of humanity, its gullibility, the process by which our beliefs are formed, and the origins of the religions we believe in and pray to. From a scientific perspective, the topic of UFOs and alien abductions holds a true treasure trove.

However, the treasure clearly has the quality of being 'Made in Earth', originating from the homeland of mankind.

Skeptical thinking is ultimately a means of constructing and understanding rational arguments.

The most important thing is to see through the scams that deceive people.

The question is not whether we like the conclusion we arrive at through a series of inferences, but whether the conclusion is properly derived from the premises or starting point, and whether the premises are true.

Humans sometimes find it easier to stubbornly reject evidence than to admit their own mistakes.

If so, we must know that we are such beings.

It is not only in magic shows and fortune-tellers' consulting rooms that nonsense, fraud, deception, frivolous thoughts and wishes appear, disguised as facts.

Unfortunately, this happens in every field, including politics, society, religion, and economics.

And this isn't limited to just one country.

Scientists make mistakes too.

Therefore, it is the scientist's job to recognize his or her weaknesses as a human being, listen to as many different opinions as possible, and be merciless in his or her self-criticism.

Science is a collective enterprise with self-correcting capabilities.

This feature works quite well.

This is where science has an overwhelming advantage over history.

Because science can do experiments.

If you can censor Darwin, you can censor any knowledge.

But who will do that censorship? Who knows that some information and insights can be discarded, while others will become necessary in 10, 100, or even 1,000 years? Can anyone possibly exist in this world with such wisdom? Clearly, there are times when judgment can and must be made regarding the safety of machines and products.

Because we don't have the resources to investigate all the possible outcomes of any given technology.

But censoring knowledge, determining what thoughts are permissible and what are not, what evidence can and cannot be explored, is the work of the thought police, a foolish and incompetent decision, and a foolish move that will lead our civilization down a long-term path to decline.

Galaxies also revolve around each other according to Newton's laws of gravity, which we are all familiar with.

The existence of gravitational lenses and the slowing rotation of binary pulsars demonstrate that general relativity holds true even in the depths of space.

We could live in a universe where the laws of nature vary depending on where we are.

But the reality is not like that.

I cannot help but feel awe before this stark fact.

But in light of the discoveries made over the past few centuries, it would be foolish to complain about reductionism.

It is not a flaw of science, but one of its greatest triumphs.

And I think the achievements of science are perfectly compatible with many religions.

There are probably many other doctrines and vested interests that worry about what science will discover in the future.

Some say it would be better not to know and ask:

If it turns out that men and women have different genetic makeup, wouldn't that be used as an excuse for men to oppress women? If genes predisposing to violence are discovered, wouldn't that be used to justify one ethnic group's oppression of another? Or even preventative measures like preemptive elimination? If mental illness is simply a problem of brain chemistry, wouldn't our efforts to maintain a sense of reality and take responsibility for our actions be meaningless? If humans aren't the special work of the Creator of the universe, if the moral codes that underpin human society are not devised by a deity but by fallible lawmakers, wouldn't our struggles to maintain social order be in vain?

These concerns are both religious and secular.

But I think that knowing what's closest to the truth, whatever it may be, and properly understanding the mistakes our communities and belief systems have made in the past, will contribute to making the world a better place.

Some people argue that the more widely the truth or the truth becomes known to the public, the more tragic things happen.

But any such claim is nothing more than an exaggeration of the situation.

Again, we are not wise enough to know which lies or which concealments of facts will help us create a better society or achieve a nobler social purpose.

Not to mention the long-term aspect.

The relationship between humans and technology is not a problem of yesterday or today. We who develop technology today and our ancestors who developed technology in the past are also human beings.

We are still developing new technologies, as we always have.

The problem is that while human weaknesses remain unchanged, technology has reached a level of destructive power never before seen, even on a planetary scale.

In these times, we cannot help but demand something unprecedented not only from science and technology but also from humanity.

So, we must now establish new morals and ethics on an unprecedented scale, that is, on a global scale.

However, scientists often take an ambivalent stance on this issue.

In other words, while we want to be recognized for the science and technology that enriches our lives, we also want to distance ourselves from the fact that science and technology are being used as tools of death, whether intentional or not.

I believe it is the duty of scientists to inform the public of potential risks, particularly those posed by science or that may arise from its use.

You might call it a prophetic mission.

Of course, caution must be exercised when issuing warnings and the risks must not be exaggerated beyond what is necessary.

However, considering that humans are creatures who cannot avoid making mistakes and that if a risk actually materializes, the consequences can be fatal, safety must be given the utmost priority.

When skepticism is applied to world affairs, there is a tendency to trivialize problems, treat them as if they were superior, or ignore them.

But whether they're being deceived or not, proponents of superstition and pseudoscience are just as human as skeptics, with feelings and a desire to understand how the world works and what our role is in it.

Skeptics may be reluctant to admit it, but they often start from much the same motivations as scientists.

However, it may be that they simply did not receive the tools necessary for that quest from their culture.

If that's true, wouldn't it be better to criticize more gently? After all, no one is born fully armed.

The essence of science is to strike a balance between two seemingly contradictory attitudes.

One is to be open to new ideas, no matter how strange or counterintuitive, and the other is to be skeptical and very thorough in examining all ideas, old or new.

Only by striking a balance between these two can we discern profound truth from outrageous nonsense.

A combination of creative and skeptical thinking is needed.

Yet there is some tension between these two seemingly contradictory attitudes.

Is it because humanity isn't yet ready to embrace science, because science is a product of chance, or because most members of our society lack the intellectual capacity to digest it? I disagree with neither of these.

The first graders I met showed a keen interest in science, and the surviving hunter-gatherers also provided valuable lessons.

These cases eloquently demonstrate the following argument:

Scientific inclinations have always been deeply rooted in us, regardless of time, place, or culture.

It is our means of survival.

It is our natural talent.

If we turn children away from science because of fears of indifference, carelessness, incompetence, and skepticism, we are robbing them of their privilege as human beings and the tools they need to thrive in the future.

I think there is only one secret.

When speaking to a general audience, don't speak as you would to your fellow scientists.

Among experts, there are words that allow you to convey your meaning immediately and accurately.

That's what's called technical terminology, academic terminology.

Scientists may use such vocabulary as part of their profession, but to the general audience, it only mystifies science.

You should use the simplest vocabulary possible.

The most important thing is to remember what you were like before you understood what I am explaining to you now.

You need to remember the parts that were almost misunderstood and explain them while being careful about them.

We must keep in mind that there was a time when we did not understand any of it.

You must recall the first steps that led you from ignorance to knowledge.

And we must never forget that every human being is born with intelligence.

This is truly the whole secret.

I believe that science is essential for any society to survive into the next century while preserving its fundamental values.

And I believe that the science of that time should not be something only for those engaged in the profession of science, but should be understood and accepted by the entire human community.

A lot of work needs to be done to make science accessible to everyone.

If our scientists don't do it, who will?

Frederick Douglass taught that learning to read and write was the path from slavery to freedom.

There are many kinds of slavery, and many kinds of freedom.

But reading is always the path to freedom.

Of course, there are urgent issues facing the nation and humanity.

However, cutting basic science research funding will not solve such problems.

Clearly, scientists are not a very effective lobbyists, nor are they particularly effective lobbyists.

But what scientists do often benefits everyone.

To abandon basic research is a product of cowardice, lack of imagination, and fantasy.

If aliens saw Earthlings giving up on the future like this, they would be shocked.

Ethnocentrism, xenophobia, and fanatic patriotism are on the rise around the world today.

Even today, many countries suppress anti-government ideology and instill false, sometimes intentionally distorted, memories in their citizens.

To those who advocate such measures of state power, science will seem subversive.

The truth that science seeks to grasp is largely independent of ethnic and cultural biases.

Science, in essence, has no borders.

Put scientists working in the same field in a room together and they will find ways to communicate even if they don't have a common language.

Because science itself is a language that transcends nationality.

Scientists are inherently globalists and readily see through any scheme to divide the one family that is humanity.

In every country, children must be taught the methods of science and the meaning of the Bill of Rights.

Dignity, humility, and a sense of community will sprout there.

In a world haunted by evil spirits, it may be the only thing that can protect us from the encroaching darkness.

Where have we heard that sound before? When prejudice against a people or nation gains ground, when famines run rampant, when national prestige and the very foundations of a nation are challenged, when we agonize over our place and purpose in the universe, or when fanaticism bubbles up around us, then those old, familiar habits of thought reach out to dominate us.

The candlelight gradually fades.

A small pool of sparks trembles.

Darkness gathers.

The evil spirits begin to stir.

Science cannot be said to be a perfect tool for pursuing knowledge.

Science is simply the best tool we have.

From this perspective, science is similar to democracy.

Science itself does not teach or advocate what human behavior should be.

But we can be sure that certain actions will lead to certain consequences.

However satisfying and reassuring it may be, I believe it is far better to understand the universe as it really is than to insist on delusion.

Pseudoscience is the exact opposite.

The hypotheses of pseudoscience are designed so that they cannot be falsified by any experiment.

It is even impossible to disprove in principle.

Adherents of pseudoscience are defensive and vigilant.

When you try to review it skeptically, it suddenly appears and interferes.

And when pseudoscientific hypotheses fail to gain scientific support, they conspire to somehow get around it.

For example, they claim that scientists are conspiring to suppress it.

Humans have been patiently and collectively investigating nature for centuries, distilling the results.

Of course, it might be easier to introduce already accomplished wisdom in a flashy way than to explain in detail this distillation process, which is riddled with all sorts of things.

Moreover, the scientific method seems like a cumbersome thing to deal with.

But this method is far more valuable than the discovery itself.

Another reason science has been successful is that error correction mechanisms are built into its core.

Some might criticize this as over-categorization, since correcting errors isn't unique to science, but I think every time we self-criticize, every time we apply our ideas to the outside world and test them, we are doing science.

When we are generous and uncritical of ourselves, when we confuse hope with fact, we slide into pseudoscience and superstition.

One of the great commandments of science is: 'Never believe arguments that appeal to authority.'

(Of course, scientists are also primates and are weak in group hierarchy, so they cannot always follow this commandment.)

Science is not only compatible with spirituality, but is also its profound source.

The feeling that arises when we recognize our place in the vast expanse of space and time, measured in light-years, or when we grasp the complexity, beauty, and subtlety of life—a feeling of elation combined with humility—is certainly mental or spiritual.

These efforts will continue as long as scientists exist.

General relativity is inadequate to describe nature at the quantum level.

But even if that were not the case, that is, even if general relativity were a valid theory at all times and everywhere, what better way to make it certain than by a concerted effort to discover its weaknesses and limitations?

This is one of the reasons why I am not very firm about organized religion.

What religious leader in the world would admit that their faith is imperfect or possibly wrong, and thus establish a research institute to uncover hidden weaknesses in their doctrines? Who would systematically research, beyond the testing of everyday life, to identify situations in which traditional religious teachings might no longer apply?

When skepticism is applied to world affairs, there is a tendency to trivialize problems, treat them as if they were superior, or ignore them.

But whether they're being deceived or not, proponents of superstition and pseudoscience are just as human as skeptics, with feelings and a desire to understand how the world works and what our role is in it.

Skeptics may be reluctant to admit it, but they often start from much the same motivations as scientists.

However, it may be that they simply did not receive the tools necessary for that exploration from their culture.

If that's true, wouldn't it be better to criticize more gently? After all, no one is born fully armed.

Unverifiable claims, unfalsifiable assertions, no matter how inspiring or awe-inspiring they may be, are worthless when it comes to truth.

What I'm saying is like asking you to believe it without any evidence.

If alien abduction stories are the result of brain physiology, hallucinations, distorted childhood memories, or fabrications, we face a very important problem.

This issue concerns the limitations of humanity, its gullibility, the process by which our beliefs are formed, and the origins of the religions we believe in and pray to. From a scientific perspective, the topic of UFOs and alien abductions holds a true treasure trove.

However, the treasure clearly has the quality of being 'Made in Earth', originating from the homeland of mankind.

Skeptical thinking is ultimately a means of constructing and understanding rational arguments.

The most important thing is to see through the scams that deceive people.

The question is not whether we like the conclusion we arrive at through a series of inferences, but whether the conclusion is properly derived from the premises or starting point, and whether the premises are true.

Humans sometimes find it easier to stubbornly reject evidence than to admit their own mistakes.

If so, we must know that we are such beings.

It is not only in magic shows and fortune-tellers' consulting rooms that nonsense, fraud, deception, frivolous thoughts and wishes appear, disguised as facts.

Unfortunately, this happens in every field, including politics, society, religion, and economics.

And this isn't limited to just one country.

Scientists make mistakes too.

Therefore, it is the scientist's job to recognize his or her weaknesses as a human being, listen to as many different opinions as possible, and be merciless in his or her self-criticism.

Science is a collective enterprise with self-correcting capabilities.

This feature works quite well.

This is where science has an overwhelming advantage over history.

Because science can do experiments.

If you can censor Darwin, you can censor any knowledge.

But who will do that censorship? Who knows that some information and insights can be discarded, while others will become necessary in 10, 100, or even 1,000 years? Can anyone possibly exist in this world with such wisdom? Clearly, there are times when judgment can and must be made regarding the safety of machines and products.

Because we don't have the resources to investigate all the possible outcomes of any given technology.

But censoring knowledge, determining what thoughts are permissible and what are not, what evidence can and cannot be explored, is the work of the thought police, a foolish and incompetent decision, and a foolish move that will lead our civilization down a long-term path to decline.

Galaxies also revolve around each other according to Newton's laws of gravity, which we are all familiar with.

The existence of gravitational lenses and the slowing rotation of binary pulsars demonstrate that general relativity holds true even in the depths of space.

We could live in a universe where the laws of nature vary depending on where we are.

But the reality is not like that.

I cannot help but feel awe before this stark fact.

But in light of the discoveries made over the past few centuries, it would be foolish to complain about reductionism.

It is not a flaw of science, but one of its greatest triumphs.

And I think the achievements of science are perfectly compatible with many religions.

There are probably many other doctrines and vested interests that worry about what science will discover in the future.

Some say it would be better not to know and ask:

If it turns out that men and women have different genetic makeup, wouldn't that be used as an excuse for men to oppress women? If genes predisposing to violence are discovered, wouldn't that be used to justify one ethnic group's oppression of another? Or even preventative measures like preemptive elimination? If mental illness is simply a problem of brain chemistry, wouldn't our efforts to maintain a sense of reality and take responsibility for our actions be meaningless? If humans aren't the special work of the Creator of the universe, if the moral codes that underpin human society are not devised by a deity but by fallible lawmakers, wouldn't our struggles to maintain social order be in vain?

These concerns are both religious and secular.

But I think that knowing what's closest to the truth, whatever it may be, and properly understanding the mistakes our communities and belief systems have made in the past, will contribute to making the world a better place.

Some people argue that the more widely the truth or the truth becomes known to the public, the more tragic things happen.

But any such claim is nothing more than an exaggeration of the situation.

Again, we are not wise enough to know which lies or which concealments of facts will help us create a better society or achieve a nobler social purpose.

Not to mention the long-term aspect.

The relationship between humans and technology is not a problem of yesterday or today. We who develop technology today and our ancestors who developed technology in the past are also human beings.

We are still developing new technologies, as we always have.

The problem is that while human weaknesses remain unchanged, technology has reached a level of destructive power never before seen, even on a planetary scale.

In these times, we cannot help but demand something unprecedented not only from science and technology but also from humanity.

So, we must now establish new morals and ethics on an unprecedented scale, that is, on a global scale.

However, scientists often take an ambivalent stance on this issue.

In other words, while we want to be recognized for the science and technology that enriches our lives, we also want to distance ourselves from the fact that science and technology are being used as tools of death, whether intentional or not.

I believe it is the duty of scientists to inform the public of potential risks, particularly those posed by science or that may arise from its use.

You might call it a prophetic mission.

Of course, caution must be exercised when issuing warnings and the risks must not be exaggerated beyond what is necessary.

However, considering that humans are creatures who cannot avoid making mistakes and that if a risk actually materializes, the consequences can be fatal, safety must be given the utmost priority.

When skepticism is applied to world affairs, there is a tendency to trivialize problems, treat them as if they were superior, or ignore them.

But whether they're being deceived or not, proponents of superstition and pseudoscience are just as human as skeptics, with feelings and a desire to understand how the world works and what our role is in it.

Skeptics may be reluctant to admit it, but they often start from much the same motivations as scientists.

However, it may be that they simply did not receive the tools necessary for that quest from their culture.

If that's true, wouldn't it be better to criticize more gently? After all, no one is born fully armed.

The essence of science is to strike a balance between two seemingly contradictory attitudes.

One is to be open to new ideas, no matter how strange or counterintuitive, and the other is to be skeptical and very thorough in examining all ideas, old or new.

Only by striking a balance between these two can we discern profound truth from outrageous nonsense.

A combination of creative and skeptical thinking is needed.

Yet there is some tension between these two seemingly contradictory attitudes.

Is it because humanity isn't yet ready to embrace science, because science is a product of chance, or because most members of our society lack the intellectual capacity to digest it? I disagree with neither of these.

The first graders I met showed a keen interest in science, and the surviving hunter-gatherers also provided valuable lessons.

These cases eloquently demonstrate the following argument:

Scientific inclinations have always been deeply rooted in us, regardless of time, place, or culture.

It is our means of survival.

It is our natural talent.

If we turn children away from science because of fears of indifference, carelessness, incompetence, and skepticism, we are robbing them of their privilege as human beings and the tools they need to thrive in the future.

I think there is only one secret.

When speaking to a general audience, don't speak as you would to your fellow scientists.

Among experts, there are words that allow you to convey your meaning immediately and accurately.

That's what's called technical terminology, academic terminology.

Scientists may use such vocabulary as part of their profession, but to the general audience, it only mystifies science.

You should use the simplest vocabulary possible.

The most important thing is to remember what you were like before you understood what I am explaining to you now.

You need to remember the parts that were almost misunderstood and explain them while being careful about them.

We must keep in mind that there was a time when we did not understand any of it.

You must recall the first steps that led you from ignorance to knowledge.

And we must never forget that every human being is born with intelligence.

This is truly the whole secret.

I believe that science is essential for any society to survive into the next century while preserving its fundamental values.

And I believe that the science of that time should not be something only for those engaged in the profession of science, but should be understood and accepted by the entire human community.

A lot of work needs to be done to make science accessible to everyone.

If our scientists don't do it, who will?

Frederick Douglass taught that learning to read and write was the path from slavery to freedom.

There are many kinds of slavery, and many kinds of freedom.

But reading is always the path to freedom.

Of course, there are urgent issues facing the nation and humanity.

However, cutting basic science research funding will not solve such problems.

Clearly, scientists are not a very effective lobbyists, nor are they particularly effective lobbyists.

But what scientists do often benefits everyone.

To abandon basic research is a product of cowardice, lack of imagination, and fantasy.

If aliens saw Earthlings giving up on the future like this, they would be shocked.

Ethnocentrism, xenophobia, and fanatic patriotism are on the rise around the world today.

Even today, many countries suppress anti-government ideology and instill false, sometimes intentionally distorted, memories in their citizens.

To those who advocate such measures of state power, science will seem subversive.

The truth that science seeks to grasp is largely independent of ethnic and cultural biases.

Science, in essence, has no borders.

Put scientists working in the same field in a room together and they will find ways to communicate even if they don't have a common language.

Because science itself is a language that transcends nationality.

Scientists are inherently globalists and readily see through any scheme to divide the one family that is humanity.

In every country, children must be taught the methods of science and the meaning of the Bill of Rights.

Dignity, humility, and a sense of community will sprout there.

In a world haunted by evil spirits, it may be the only thing that can protect us from the encroaching darkness.

--- From the text

Publisher's Review

A classic of the modern skeptic movement

A scientific romance about a scientist who has been fascinated by the cosmos all his life.

The first half of this book debunks a litany of bizarre nonsense, including UFOs ridden by aliens, abductions by aliens, continents that sank due to disaster, the advanced science and technology of an ancient civilization, the Face of Mars, mysterious crop circles secretly drawn in wheat fields, devil worship, reincarnated New Age gurus, transcendental meditation, pseudoscience such as psychic surgery, and pseudo-religions.

In fact, there are many skeptical books that debunk these pseudosciences, denounce their absurd logic, and expose how gullible humans are, even to the point of deceiving themselves.

This book by Carl Sagan is also one of these books.

However, the unique feature of this book is that it explains why such pseudo-nonsense repeatedly captures people's hearts, and what tragedies this trend of easy deception and easy belief has caused in human history, society, and culture, within the larger context of human evolution and civilization.

This is one of the reasons why this book is considered a key classic of the modern skepticism movement that began in the late 20th century.

The latter part of this book explains what Sagan himself believes to be the essence and spirit of science, based on his diagnosis that these pseudo-nonsense lies at the root of misuse of science, misunderstanding of science, and even antipathy toward science.

For Sagan, the core spirit of science is not much different from training a critical spirit based on the premise that humans inevitably make mistakes, that the human mind and thinking are prone to traps, and that they can even deceive themselves.

In this respect, Sagan breaks away from the pseudo-scientific narrative that swept American society and culture in the late 20th century and explains how slavery, which countless religious and intellectuals defended with all kinds of logic for thousands of years all over the world, collapsed; how the witch hunts unique to European civilization, which burned countless innocent old women and girls to death, began, spread, and disappeared; and why American education, which was full of “Yankee genius” that admired science and technology and admired inventors, turned anti-science. By selecting and introducing various cases from human history and culture, he vividly shows what errors humans have made when they fell into the trap of faulty thinking, and depicts the role that skeptical thinking and the scientific method, which is a representative example of it, played in escaping from that trap.

For Carl Sagan, science minimizes the inevitable human error potential and fosters a critical spirit through the concept of falsifiability and the practice of verification through experimentation.

But why does Carl Sagan devote so much energy to criticizing pseudoscience? In reality, scientists simply ignore pseudoscience and similar claims.

Richard Dawkins speaks of a concept called the "two-chair effect" and refuses to debate creation scientists (who play in biology what UFO believers do in astronomy).

The idea is that the two chairs placed side by side on the podium, with both sides speaking for equal time and with equal weight, can create the illusion that both opinions are equal and valid.

Astronomers and physicists refuse to debate publicly with UFO advocates and avoid meeting with self-proclaimed alien abduction victims.

However, Sagan had been hosting public discussions on UFOs since the 1970s, and did not hesitate to meet with alien abductees to write this book.

Some scientists have publicly criticized him and even threatened to strip him of his academic position.

(It is described in detail in the book.

(See Chapter 5) Because I believe that the same wind as science is at the root of pseudoscience.

It is the public's taste for the wonders of the universe and their desire to know about the new knowledge discovered by science.

Pseudoscience, based on this public desire, seeks to exploit the methods, results, or reputation of science without believing or accepting the skeptical nature of science.

Carl Sagan said this about pseudoscience:

Pseudoscience has a powerful emotional appeal.

Science often fails to satisfy this need.

Pseudoscience fosters fantasies about personal powers we don't possess but crave—powers that are today granted to comic book superheroes and that were once attributed to gods.

In some cases, pseudoscience promises to satisfy people's spiritual hunger, cure diseases, and make death not the end.

Pseudoscience gives us back our belief that we are the center of the universe and that we are important beings.

Pseudoscience assures us that we are inextricably linked and connected to the universe.

- In the text

Sagan diagnoses the cause of the proliferation and popularity of this pseudoscience as the lack of popularization of science, including science education.

And throughout the book, he criticizes scientists in academia for neglecting the popularization of science.

So what is the difference between science and pseudoscience, and how can we solve the problems caused by pseudoscience?

Perhaps the biggest difference between science and pseudoscience is that science acknowledges human imperfection and fallibility much more sharply than pseudoscience (or the revelation of 'infallibility').

If we do not fully accept the possibility of human error, errors (or irreversible, fatal mistakes) will follow us forever.

But if we can muster up a little courage and look at ourselves as we are, and reflectively overcome the disappointment and regret that arise in the process, our possibilities will increase enormously.

… …

The first thing we must do to popularize science is to tell the truth about the twists and turns that have accompanied even the greatest scientific discoveries.

We need to tell the true story of what misunderstandings there were, what path changes there were, and what conflicts occurred in the research field between those who stubbornly resisted change and those who pursued it.

But science textbooks, or rather most textbooks, do not attempt to cover this history well.

Humans have been patiently and collectively investigating nature and distilling the results over centuries.

Of course, it might be easier to introduce already accomplished wisdom in a flashy way than to explain in detail this distillation process, which is riddled with all sorts of things.

Moreover, the scientific method seems like a cumbersome thing to deal with.

But this method is far more valuable than the discovery itself.

- In the text

In fact, the 30 or so books Carl Sagan published throughout his life, including Cosmos, were based on his diagnosis and awareness of the problem.

The stories and discoveries of scientists that science textbooks don't teach us, and the teachings that exploring the cosmos is actually exploring humanity, which he has written in his extensive writings, make him remembered as the greatest science evangelist and science writer of the 20th century, and as the greatest scientist even in the 2020s, a quarter of a century after his death.

In an age where the evil spirit of anti-intellectualism is rampant and the candle of science is wavering

Dreaming of a delightful combination of the spirit of doubt and the sensibility of wonder

Thus, the important feature of this book is that it systematically provides an understanding of Carl Sagan's views on science, including his thoughts on the nature of science, scientific methods, the meaning of science, the ethics of science, and the popularization of science.

This book contains the core concepts of Carl Sagan's scientific thought that any Carl Sagan researcher would study someday: skepticism based on the inevitable possibility of human error, verification through falsification and experimentation, and a bullshit detector to train the critical spirit.

Another feature is that it gives a glimpse into Carl Sagan's political and democratic views.

Carl Sagan mentions the similarities between science and democracy throughout this book.

And furthermore, practical relevance.

What both science and democracy have in common is that they assume human fallibility as a default and have built-in functions to correct those errors.

Of course, Sagan is well aware that science and democracy are not the same thing, and that democracy does not come from the scientific method, nor does science come from democracy, and he warns in his book not to confuse them.

Of course, science and democracy operate in fundamentally different ways.

In a democratic system, institutions and policies are decided by voting, but scientific truth is not decided by majority vote.

Scientists don't vote to determine what is true or false.

However, it is argued that science is an important pillar of democracy.

Science invites us into the realm of facts.

Even if the facts do not match our preconceptions.

Science encourages us to first generate alternative hypotheses in our heads and then see which one best fits the facts.

It teaches us to maintain a very delicate balance: to be open to new ideas, no matter how heretical, while at the same time maintaining the utmost rigor and skepticism, scrutinizing them thoroughly, regardless of whether they are new ideas or established wisdom.

This kind of thinking is also an essential tool for sustaining democracy in times of change.

- In the text

It appears that Sagan was feeling a considerable sense of crisis in the early to mid-1990s when he was writing this book.

The Cold War is over, but conflicts persist; globalization has begun, but nationalism and religious fundamentalism only intensify; the century ended with the great triumph of the Pax Americana, but the United States is in decline due to the hollowing out of industry and the devastation of education; we sent probes to the ends of the solar system and discovered amazing things about other worlds, but pseudoscience and pseudo-religions appear only under different packaging. Carl Sagan may have had a premonition of the chaos of the first two decades of the 21st century, which began with the 9/11 terrorist attacks and ended with a pandemic.

Perhaps his concerns and hopes are deeply embedded in the title and subtitle of this book: A World Haunted by Demons: Science, a Candle in the Darkness.

Perhaps for this reason, Sagan devotes a significant portion of this book to emphasizing the importance of science education and advocating for its reform.

While some of the specific improvements he proposed have long since expired, the underlying spirit remains a valuable insight worth pondering.

As Carl Sagan said.

The ability to doubt and the ability to feel wonder are both useless skills unless they are trained.

These two things should be the main goal of public education to make marriage amicable in the minds of young students.

I just hope that such a charming family drama will be properly presented in the mass media, especially television.

How wonderful it would be if people could properly manage these two things—if they could cherish the sense of wonder rather than unjustifiably reject or discard it, if they could be generous and open to diverse ideas, and if they could make it second nature to demand rigorous standards for evidence. And these standards for evidence should be equally rigorous, regardless of whether they hold it dear or, if possible, reject it.

- In the text

The final mission of Carl Sagan, the guardian of the scientific spirit

This book was published at the end of 1995, a year before Carl Sagan passed away.

(The copyright notice indicates that it was published in 1996.

Sales began in 1995.) If his wife, Ann Druyan, compiled his writings and published them in the year after his death, 『Epilogue (Billions & Billions)』 (1997, Korean edition published in 2001) and 『The Varieties of Scientific Experience』 (2006, Korean edition published in 2010), then this book is the last book he published during his lifetime, while suffering from myeloid blood cancer (leukemia).

A Korean version was published in 2001, but is now out of print.

This book was translated by the same translator, Professor Lee Sang-heon of Sogang University's Jeonin Education Center, who added translations that were missing from the previous Korean edition, corrected errors in the existing translation, and translated it anew when necessary.

For a long time, there were inquiries from Carl Sagan readers and fans, who can be called the Cosmos generation, for a republication, and Science Books Co., Ltd. published it through an official copyright contract.

Although nearly a generation has passed since the first publication of this book in 2022, the need for the harmonious combination of the spirit of doubt and the sensibility of wonder that Carl Sagan raised, perhaps now more than ever, is crucial.

The demons of ancient Greece became witches in the Middle Ages and aliens during the Cold War.

Even now, somewhere, they may be running rampant under different names and masks.

The spirit that Carl Sagan criticized as irrational and anti-science is now roaming the world under the guise of post-truth or anti-intellectualism.

In that sense, Carl Sagan's final mission as a guardian of the scientific spirit may not be over yet.

A scientific romance about a scientist who has been fascinated by the cosmos all his life.

The first half of this book debunks a litany of bizarre nonsense, including UFOs ridden by aliens, abductions by aliens, continents that sank due to disaster, the advanced science and technology of an ancient civilization, the Face of Mars, mysterious crop circles secretly drawn in wheat fields, devil worship, reincarnated New Age gurus, transcendental meditation, pseudoscience such as psychic surgery, and pseudo-religions.

In fact, there are many skeptical books that debunk these pseudosciences, denounce their absurd logic, and expose how gullible humans are, even to the point of deceiving themselves.

This book by Carl Sagan is also one of these books.

However, the unique feature of this book is that it explains why such pseudo-nonsense repeatedly captures people's hearts, and what tragedies this trend of easy deception and easy belief has caused in human history, society, and culture, within the larger context of human evolution and civilization.

This is one of the reasons why this book is considered a key classic of the modern skepticism movement that began in the late 20th century.

The latter part of this book explains what Sagan himself believes to be the essence and spirit of science, based on his diagnosis that these pseudo-nonsense lies at the root of misuse of science, misunderstanding of science, and even antipathy toward science.

For Sagan, the core spirit of science is not much different from training a critical spirit based on the premise that humans inevitably make mistakes, that the human mind and thinking are prone to traps, and that they can even deceive themselves.

In this respect, Sagan breaks away from the pseudo-scientific narrative that swept American society and culture in the late 20th century and explains how slavery, which countless religious and intellectuals defended with all kinds of logic for thousands of years all over the world, collapsed; how the witch hunts unique to European civilization, which burned countless innocent old women and girls to death, began, spread, and disappeared; and why American education, which was full of “Yankee genius” that admired science and technology and admired inventors, turned anti-science. By selecting and introducing various cases from human history and culture, he vividly shows what errors humans have made when they fell into the trap of faulty thinking, and depicts the role that skeptical thinking and the scientific method, which is a representative example of it, played in escaping from that trap.

For Carl Sagan, science minimizes the inevitable human error potential and fosters a critical spirit through the concept of falsifiability and the practice of verification through experimentation.

But why does Carl Sagan devote so much energy to criticizing pseudoscience? In reality, scientists simply ignore pseudoscience and similar claims.

Richard Dawkins speaks of a concept called the "two-chair effect" and refuses to debate creation scientists (who play in biology what UFO believers do in astronomy).

The idea is that the two chairs placed side by side on the podium, with both sides speaking for equal time and with equal weight, can create the illusion that both opinions are equal and valid.

Astronomers and physicists refuse to debate publicly with UFO advocates and avoid meeting with self-proclaimed alien abduction victims.

However, Sagan had been hosting public discussions on UFOs since the 1970s, and did not hesitate to meet with alien abductees to write this book.

Some scientists have publicly criticized him and even threatened to strip him of his academic position.

(It is described in detail in the book.

(See Chapter 5) Because I believe that the same wind as science is at the root of pseudoscience.

It is the public's taste for the wonders of the universe and their desire to know about the new knowledge discovered by science.

Pseudoscience, based on this public desire, seeks to exploit the methods, results, or reputation of science without believing or accepting the skeptical nature of science.

Carl Sagan said this about pseudoscience:

Pseudoscience has a powerful emotional appeal.

Science often fails to satisfy this need.

Pseudoscience fosters fantasies about personal powers we don't possess but crave—powers that are today granted to comic book superheroes and that were once attributed to gods.

In some cases, pseudoscience promises to satisfy people's spiritual hunger, cure diseases, and make death not the end.

Pseudoscience gives us back our belief that we are the center of the universe and that we are important beings.

Pseudoscience assures us that we are inextricably linked and connected to the universe.

- In the text

Sagan diagnoses the cause of the proliferation and popularity of this pseudoscience as the lack of popularization of science, including science education.

And throughout the book, he criticizes scientists in academia for neglecting the popularization of science.

So what is the difference between science and pseudoscience, and how can we solve the problems caused by pseudoscience?

Perhaps the biggest difference between science and pseudoscience is that science acknowledges human imperfection and fallibility much more sharply than pseudoscience (or the revelation of 'infallibility').

If we do not fully accept the possibility of human error, errors (or irreversible, fatal mistakes) will follow us forever.

But if we can muster up a little courage and look at ourselves as we are, and reflectively overcome the disappointment and regret that arise in the process, our possibilities will increase enormously.

… …

The first thing we must do to popularize science is to tell the truth about the twists and turns that have accompanied even the greatest scientific discoveries.

We need to tell the true story of what misunderstandings there were, what path changes there were, and what conflicts occurred in the research field between those who stubbornly resisted change and those who pursued it.

But science textbooks, or rather most textbooks, do not attempt to cover this history well.

Humans have been patiently and collectively investigating nature and distilling the results over centuries.

Of course, it might be easier to introduce already accomplished wisdom in a flashy way than to explain in detail this distillation process, which is riddled with all sorts of things.

Moreover, the scientific method seems like a cumbersome thing to deal with.

But this method is far more valuable than the discovery itself.

- In the text

In fact, the 30 or so books Carl Sagan published throughout his life, including Cosmos, were based on his diagnosis and awareness of the problem.

The stories and discoveries of scientists that science textbooks don't teach us, and the teachings that exploring the cosmos is actually exploring humanity, which he has written in his extensive writings, make him remembered as the greatest science evangelist and science writer of the 20th century, and as the greatest scientist even in the 2020s, a quarter of a century after his death.

In an age where the evil spirit of anti-intellectualism is rampant and the candle of science is wavering

Dreaming of a delightful combination of the spirit of doubt and the sensibility of wonder

Thus, the important feature of this book is that it systematically provides an understanding of Carl Sagan's views on science, including his thoughts on the nature of science, scientific methods, the meaning of science, the ethics of science, and the popularization of science.

This book contains the core concepts of Carl Sagan's scientific thought that any Carl Sagan researcher would study someday: skepticism based on the inevitable possibility of human error, verification through falsification and experimentation, and a bullshit detector to train the critical spirit.

Another feature is that it gives a glimpse into Carl Sagan's political and democratic views.

Carl Sagan mentions the similarities between science and democracy throughout this book.

And furthermore, practical relevance.

What both science and democracy have in common is that they assume human fallibility as a default and have built-in functions to correct those errors.

Of course, Sagan is well aware that science and democracy are not the same thing, and that democracy does not come from the scientific method, nor does science come from democracy, and he warns in his book not to confuse them.

Of course, science and democracy operate in fundamentally different ways.

In a democratic system, institutions and policies are decided by voting, but scientific truth is not decided by majority vote.

Scientists don't vote to determine what is true or false.

However, it is argued that science is an important pillar of democracy.

Science invites us into the realm of facts.

Even if the facts do not match our preconceptions.

Science encourages us to first generate alternative hypotheses in our heads and then see which one best fits the facts.

It teaches us to maintain a very delicate balance: to be open to new ideas, no matter how heretical, while at the same time maintaining the utmost rigor and skepticism, scrutinizing them thoroughly, regardless of whether they are new ideas or established wisdom.

This kind of thinking is also an essential tool for sustaining democracy in times of change.

- In the text

It appears that Sagan was feeling a considerable sense of crisis in the early to mid-1990s when he was writing this book.

The Cold War is over, but conflicts persist; globalization has begun, but nationalism and religious fundamentalism only intensify; the century ended with the great triumph of the Pax Americana, but the United States is in decline due to the hollowing out of industry and the devastation of education; we sent probes to the ends of the solar system and discovered amazing things about other worlds, but pseudoscience and pseudo-religions appear only under different packaging. Carl Sagan may have had a premonition of the chaos of the first two decades of the 21st century, which began with the 9/11 terrorist attacks and ended with a pandemic.

Perhaps his concerns and hopes are deeply embedded in the title and subtitle of this book: A World Haunted by Demons: Science, a Candle in the Darkness.

Perhaps for this reason, Sagan devotes a significant portion of this book to emphasizing the importance of science education and advocating for its reform.

While some of the specific improvements he proposed have long since expired, the underlying spirit remains a valuable insight worth pondering.

As Carl Sagan said.

The ability to doubt and the ability to feel wonder are both useless skills unless they are trained.

These two things should be the main goal of public education to make marriage amicable in the minds of young students.

I just hope that such a charming family drama will be properly presented in the mass media, especially television.

How wonderful it would be if people could properly manage these two things—if they could cherish the sense of wonder rather than unjustifiably reject or discard it, if they could be generous and open to diverse ideas, and if they could make it second nature to demand rigorous standards for evidence. And these standards for evidence should be equally rigorous, regardless of whether they hold it dear or, if possible, reject it.

- In the text

The final mission of Carl Sagan, the guardian of the scientific spirit

This book was published at the end of 1995, a year before Carl Sagan passed away.

(The copyright notice indicates that it was published in 1996.

Sales began in 1995.) If his wife, Ann Druyan, compiled his writings and published them in the year after his death, 『Epilogue (Billions & Billions)』 (1997, Korean edition published in 2001) and 『The Varieties of Scientific Experience』 (2006, Korean edition published in 2010), then this book is the last book he published during his lifetime, while suffering from myeloid blood cancer (leukemia).

A Korean version was published in 2001, but is now out of print.

This book was translated by the same translator, Professor Lee Sang-heon of Sogang University's Jeonin Education Center, who added translations that were missing from the previous Korean edition, corrected errors in the existing translation, and translated it anew when necessary.

For a long time, there were inquiries from Carl Sagan readers and fans, who can be called the Cosmos generation, for a republication, and Science Books Co., Ltd. published it through an official copyright contract.

Although nearly a generation has passed since the first publication of this book in 2022, the need for the harmonious combination of the spirit of doubt and the sensibility of wonder that Carl Sagan raised, perhaps now more than ever, is crucial.

The demons of ancient Greece became witches in the Middle Ages and aliens during the Cold War.

Even now, somewhere, they may be running rampant under different names and masks.

The spirit that Carl Sagan criticized as irrational and anti-science is now roaming the world under the guise of post-truth or anti-intellectualism.

In that sense, Carl Sagan's final mission as a guardian of the scientific spirit may not be over yet.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: February 28, 2022

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 672 pages | 1,114g | 152*224*35mm

- ISBN13: 9791192107226

- ISBN10: 1192107225

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)