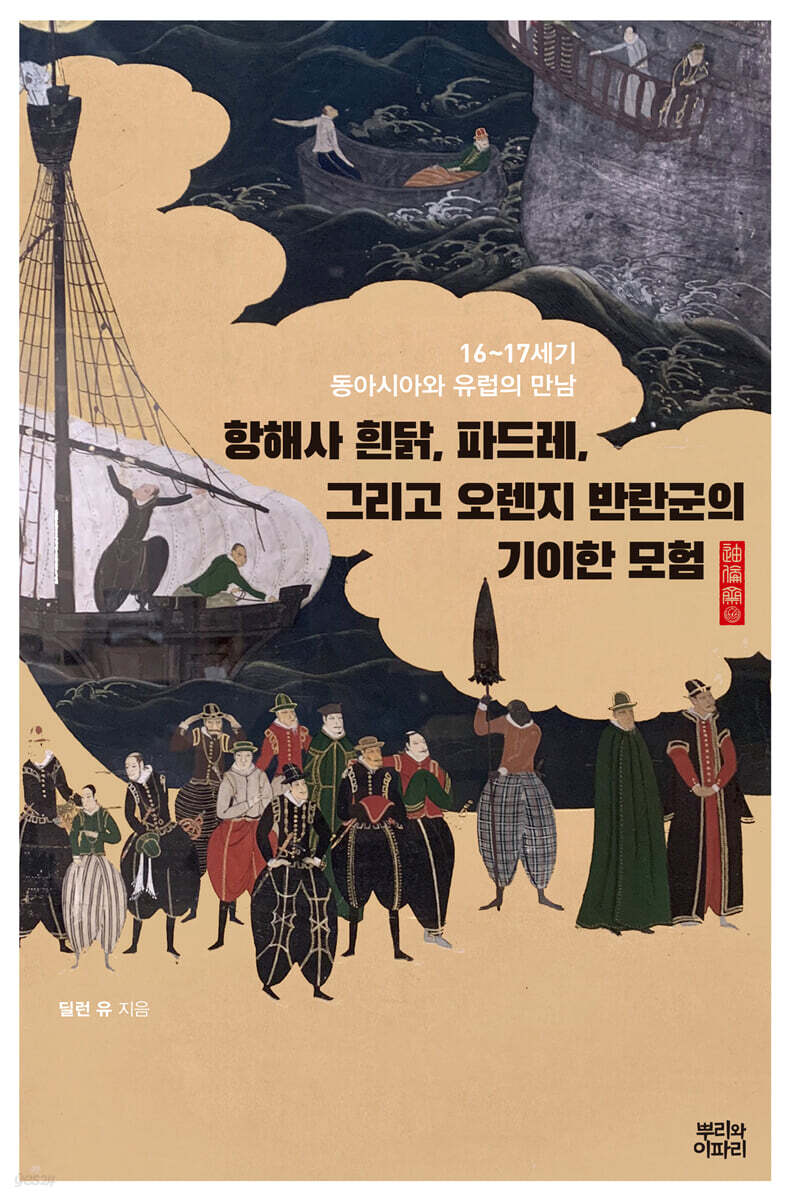

The Bizarre Adventures of the Navigator, White Chicken, Padre, and the Orange Rebels

|

Description

Book Introduction

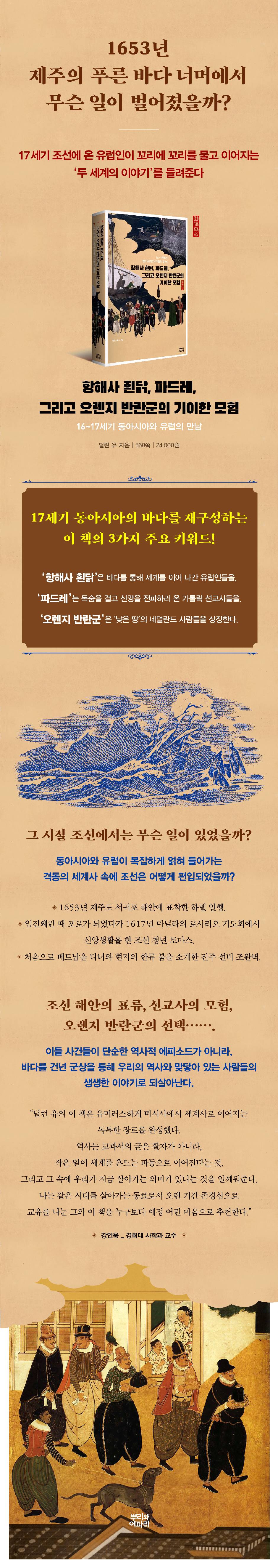

What happened beyond the blue sea of Jeju in 1653?

A European who came to Joseon in the 17th century tells a story of two worlds that continues on and on.

This book is about people who, like those who crash-landed on the shores of Joseon 370 years ago and told stories and begged for food to survive the harsh winter of the global Little Ice Age in the 17th century, crossed the vast oceans and traveled to various parts of the world, meeting people different from themselves, sometimes fighting, and sometimes forming relationships.

In the bitterly cold winter of 1657, Hamel and his crew, who were trying to pass the time by telling stories in Gangjin, South Jeolla Province, were among those swept up in the waves of this tectonic shift.

The reason I begin with the story of Hamel and his crew is because the stories of so many people were intertwined before their arrival, and even after their escape from Joseon, so many people continued to tell their stories on this stage.

A sea of storms and turbulence unfolded before the era that brought us one step closer to the modern era we know unfolded.

A European who came to Joseon in the 17th century tells a story of two worlds that continues on and on.

This book is about people who, like those who crash-landed on the shores of Joseon 370 years ago and told stories and begged for food to survive the harsh winter of the global Little Ice Age in the 17th century, crossed the vast oceans and traveled to various parts of the world, meeting people different from themselves, sometimes fighting, and sometimes forming relationships.

In the bitterly cold winter of 1657, Hamel and his crew, who were trying to pass the time by telling stories in Gangjin, South Jeolla Province, were among those swept up in the waves of this tectonic shift.

The reason I begin with the story of Hamel and his crew is because the stories of so many people were intertwined before their arrival, and even after their escape from Joseon, so many people continued to tell their stories on this stage.

A sea of storms and turbulence unfolded before the era that brought us one step closer to the modern era we know unfolded.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Chapter 1: Starting the Story

If you're curious about the title of the book...

The experiment of 'words' that this book will attempt

Chapter 2: The Tempest of the East China Sea: The Strange Encounter between Baijie and Hotan Bay

The end of Baek-gye and H-h-n-y-m-s-h-n

Beltevrey or Parkyeon

The Auverkerk in the typhoon

Chapter 3: The Emergence of the Nanman

Jiwanmyeonjesu from Bodonggaryu

Everything in the World, 『Hwahansamjaedohoe』

Introducing the Southern Manchurian people of Yeosong

Introducing the Amahang Nammanin

Bulrangi coming on a black ship

The Adventures of a Braggart

Society of Jesus, Societas Iesu

Why did Eun appear?

Xavier's soft landing

The birth of Nagasaki

The Prodigal Son, the Transformer, and the Wise Man

Bulanggipo and Joseon envoys

Rodrigues, the enlightened one

Hidden Christian

What is the great way of faith?

Found it! The legendary Christang

Discovery of the Itzlerye people

Macau Gentleman, Capitan Mor

Spain across the Pacific

Silver Lining - Japan and Spain

The sparkling air of Potosi

International Currency Piece of Eight

Spain's anxious mind

Los Españoles, the Guardians of the Golden Mountain

A brief honeymoon between Japan and Spain

Thomas's Sea

Chapter 4: The Two Princes and the Pauper

Princes and Princesses of Burgundy

The story of the division of Spain and Portugal

Until the birth of Spain and the Habsburg princes

Prince of Flanders

The Beggar and the Orange Prince

Flames of Rebellion

Chapter 5: The Land of the Red Mo-in

Blue Ocean

Valley of the Winds - Baihart

The Road to the East Indies

Saeongjima Expedition

Yayos and the Toad Magic

Tokubei Tenjiku, who visited India

The Adventures of Early Perfection

A street corner warehouse in Kyoto

Holding a certificate with a red seal

Annam's celebrity Lee Soo-kwang

『Choi Cheok Jeon』-Show Me the Truth!

The appearance of Aranta

The king of that country was Gomophaea

I need a letter from the prince!

The World of Tokugawa Ieyasu

I am a legitimate pirate!

Captain China

Nicholas Yi-kwan, Zheng Zhilong

Problematic Person, Nawitz

General Zheng Zhilong, Liberation Army

Today is also peaceful Tai Oan

The End of the Empire, Isla Hermosa

The people who lived on the island

San Salvador and San Domingo

Empire and Rebels at the End of the World

Chapter 6: The Never-ending Story

Abolition of the Haegeum and Tojinyashiki

Beltevrey's Choice

Going out

To read more details

Source of the illustration

If you're curious about the title of the book...

The experiment of 'words' that this book will attempt

Chapter 2: The Tempest of the East China Sea: The Strange Encounter between Baijie and Hotan Bay

The end of Baek-gye and H-h-n-y-m-s-h-n

Beltevrey or Parkyeon

The Auverkerk in the typhoon

Chapter 3: The Emergence of the Nanman

Jiwanmyeonjesu from Bodonggaryu

Everything in the World, 『Hwahansamjaedohoe』

Introducing the Southern Manchurian people of Yeosong

Introducing the Amahang Nammanin

Bulrangi coming on a black ship

The Adventures of a Braggart

Society of Jesus, Societas Iesu

Why did Eun appear?

Xavier's soft landing

The birth of Nagasaki

The Prodigal Son, the Transformer, and the Wise Man

Bulanggipo and Joseon envoys

Rodrigues, the enlightened one

Hidden Christian

What is the great way of faith?

Found it! The legendary Christang

Discovery of the Itzlerye people

Macau Gentleman, Capitan Mor

Spain across the Pacific

Silver Lining - Japan and Spain

The sparkling air of Potosi

International Currency Piece of Eight

Spain's anxious mind

Los Españoles, the Guardians of the Golden Mountain

A brief honeymoon between Japan and Spain

Thomas's Sea

Chapter 4: The Two Princes and the Pauper

Princes and Princesses of Burgundy

The story of the division of Spain and Portugal

Until the birth of Spain and the Habsburg princes

Prince of Flanders

The Beggar and the Orange Prince

Flames of Rebellion

Chapter 5: The Land of the Red Mo-in

Blue Ocean

Valley of the Winds - Baihart

The Road to the East Indies

Saeongjima Expedition

Yayos and the Toad Magic

Tokubei Tenjiku, who visited India

The Adventures of Early Perfection

A street corner warehouse in Kyoto

Holding a certificate with a red seal

Annam's celebrity Lee Soo-kwang

『Choi Cheok Jeon』-Show Me the Truth!

The appearance of Aranta

The king of that country was Gomophaea

I need a letter from the prince!

The World of Tokugawa Ieyasu

I am a legitimate pirate!

Captain China

Nicholas Yi-kwan, Zheng Zhilong

Problematic Person, Nawitz

General Zheng Zhilong, Liberation Army

Today is also peaceful Tai Oan

The End of the Empire, Isla Hermosa

The people who lived on the island

San Salvador and San Domingo

Empire and Rebels at the End of the World

Chapter 6: The Never-ending Story

Abolition of the Haegeum and Tojinyashiki

Beltevrey's Choice

Going out

To read more details

Source of the illustration

Detailed image

Into the book

How, and what stories, did the people of Gangjin summon these Dutchmen? By the time they arrived in Gangjin, some of them already spoke Korean quite well.

I sometimes imagine the sight of the big-nosed, wide-eyed people sitting in the guest house on a long winter night, talking in their still-clumsy Korean about the cities of the Netherlands across the distant sea, the seas of India, the golden beaches of Africa, and the deep forests of New Amsterdam, and the topknot-haired Koreans listening to them, adding interjections.

--- p.12

As you can see from the original image, the name 'ㅎㆎㄴ듥쓥솎ㄴ' recorded here as the leader is written in Korean.

In the records of Yu Deuk-gong mentioned earlier, the name was written in Korean, that is, translated into Korean.

The text has something to say.

That's true.

In Jeju, there were still names written in Korean.

The leader was Hyeon-deung-yam-seon-n, and the craftsman who steers the ship was called Gi-ta-gong, or navigator. When Hyeon-deung-yam-seon-n was written in Chinese characters, it was transferred to Baek-gye-ya-eum-sa-eun.

Baekgye literally means ‘white chicken.’

Oh, then! Did you translate ㅎㆎㄴ듥 into white chicken?

--- pp.33-34

If you read it, you will notice that the worlds that Beltevrey and Hamel knew were subtly different from each other in this conversation.

Hamel had already said that the Dutch were trading with Japan on a regular basis, but Weltevree knew that Japan did not allow trade with foreign countries and that anyone who tried to go there would probably end up dead.

Hamel further reports that he felt that Beltevrey was actively trying to persuade him not to even think about returning.

With a twenty-year time difference between these two groups, aren't they perhaps Dutch people from entirely different parallel universes? What was happening beyond the blue seas of 17th-century Jeju Island?

--- p.55

Rukui began to spread new knowledge and beliefs enthusiastically through his network, and interested and responsive scholars began to seek out Matteo Ricci.

As I explained, Rukui was originally an insider in the Confucian scholar network in the Jiangnan region of China, and the more he learned from Matteo Ricci, the more he felt that it would be better to follow the Confucian approach rather than Buddhism, and that only then would he be able to enter the upper echelons of Chinese society.

And Matteo Ricci studied Chinese classics through his connections with Ming Dynasty scholars.

In the process, the existing approach of borrowing Buddhism from the Ruggieri style was gradually abandoned and a method of coexistence between Catholicism and Chinese Confucianism was considered.

--- p.123

Among the surviving Christians after Christianity was completely banned, there were those who hid their faith and lived in hiding.

These are the people who risked their lives to protect their faith and lived in hiding for 250 years, only to surprise the world by reappearing when Europeans returned to Japan in the late 19th century.

These people are called 'Kakure Kirishitan', meaning 'hidden Christians'.

Until the Edo shogunate stabilized and banned Catholicism in the early 17th century, the main Christian areas were Kyushu and Kyoto, and they were generally established in a significant part of western Japan.

In the early stages of oppression, it started with banishments and crackdowns, but gradually the level of prohibition became oppressive.

After the Shimabara Rebellion, arguably the worst of the crisis, was suppressed in the 1630s, Christianity in Japan appeared to have been virtually "eradicated."

--- p.134

Sometime between June 25 and 30, 1605, four years after the Catholic Church was established, a guest came to visit Matteo Ricci.

Matteo Ricci welcomed the old scholar guest, invited him inside, and then knelt before the statue and worshipped it.

Records show that there was a statue of John the Baptist, a statue of the Virgin Mary holding the baby Jesus, and statues of four saints surrounding it.

Then, this old Chinese scholar also followed Richie's example by kneeling and bowing down.

And a 60-year-old scholar who identified himself as Ngai, a native of Chafamfu (Kaifeng Prefecture, Hunan Province) and a Jinshi official, said that he had come up to Beijing from his hometown to take the exam for his doctorate, and upon reading an article about Westerners who had arrived and opened a temple, he came to see them, thinking that they might be of the same religion as him.

At first, Rich was surprised to hear that Ngai was a Christian, a group that had existed in China since the time of Kublai Khan, but what was even more surprising was that Ngai was an Israelite, that is, a Jew.

--- p.150

Of course, the Ming court did not initially encourage this flow of silver circulation and the practice of paying taxes or transactions with silver, but the existing paper money system was already severely devalued and the complex in-kind tax system could not support the Ming economic system, so around the end of the 1560s, a new tax system suggested by Zhang Juzheng was implemented, mainly in Jiangnan.

This new system is called the 'One Article Whip Law'.

In the West, it is called 'single whip tax reform' in English.

If I had to translate it, it would be something like "A tax revision that can be easily handled like a single whipping." At first, I wondered what that meant, but then I realized it was a direct translation of the "one-day tax bill."

To put it in a very simple version, he surveyed the land of China and applied all the complicated and difficult taxes in kind as land tax and poll tax, and had them paid in silver.

And regardless of whether you consider the traditional interpretation or the recent revisionist economic history interpretation, there is no great disagreement that this one-year policy was the catalyst for the flow of silver from all over the world into China for nearly four centuries.

So where did all that silver come from?

--- pp.197-198

With that in mind, let's look at the gold-silver ratio above.

Rather than bringing the silver produced in Potosi to Spain and distributing it in the European market, taking it to Manila and taking it to China, even after paying the various risks of the voyage, would yield roughly twice the profit mathematically.

In fact, Jan Huygen van Linschoten, who played a huge role in the Dutch expansion into the East Indies in the 17th century, wrote to his parents while working in Goa, India, in a letter, “From here in Goa, India to China or Japan is as far as from here to Lisbon. If I have 200 or 300 gold ducats now, it will be worth 600 or 700 ducats there.”

In fact, some studies suggest that this opportunity for profit drove the Spanish, Macau-Manila, Manila-Fujian, and Japan-Macau-Portugal lines into a madness of getting rich quick.

--- p.209

This is a true story about a young Joseon man who was captured by the Japanese army during the Imjin War, became a Christian, and finally became free. He went to the Philippines in 1617, where he was practicing his faith at a Rosary prayer meeting in Manila. He went to Joseon with the priests who had cared for him, crossed the rough South Seas to Nagasaki to spread the faith that had saved him, and braved hardships to finally return to Joseon.

This is not a novel.

Actually, I have not yet confirmed the Joseon side's records of this incident.

First of all, in 『Sillok』, 『Seungjeongwon Diary』, etc., I could not find any record of the repatriation of the son of a high-ranking official from Japan in 1618, the 10th year of King Gwanghae's reign.

However, in 1617, the second Joseon envoy, who was trying to normalize diplomatic relations with Japan and bring back the exhausted Joseon people, stayed in Japan for almost half a year, and brought back Joseon people who had survived the chaos and changed the country and had begun to settle in Japan.

The first exorcism took place in 1607, and the second exorcism occurred in 1617.

--- pp.243-244

And in Linthorton's book, 'Itinerary of Voyages', 'Korea' also appears.

After a long explanation of Japan, the description of Korea Island and Macau follows.

“Not far from the coast of Sina, at 34 and 356 degrees, slightly above the horizon, is a place called 'Insula de Core.'

There is a brief record that says, “Nothing is known about this island, neither its size nor its population nor its resources.”

This is currently known to be the first record describing Korea among the records of the Western European Age of Exploration.

The information about Korea mentioned in this 『Itinerary』 was not updated much even after 28 years, so Beltevrey, who had drifted ashore in Jeju, even knew that people were eaten in Korea.

--- p.315

After suppressing the Shimabara Rebellion, the Edo Bakufu began to exert full control over all of Japan.

As seen in Park Ji-won's article, the Edo shogunate even went so far as to request cooperation from Joseon to prevent any possible Christian uprising.

In 1712, nearly 70 years after the Shimabara Rebellion, the expulsion of Catholics and the Shimabara Rebellion were mentioned in the 『Overseas Reports』, a report on international affairs collected and submitted from Japan by Im Su-gan of the diplomatic mission in the year of Shinmyo.

(……) Here, the famous statue-stepping ‘Fumie’ is even mentioned.

In the end, it was a ritual to expose hidden Christians by making them step on the crucifix or the Virgin Mary statue. In Europe, it was famous as a symbol of Japan's anti-Christian culture, and an episode even appeared in Gulliver's Travels.

--- pp.326-327

But, you know.

What if there had been a Korean who had traveled to Southeast Asia as a clerk on the Nanban trading ship of the Suminokura merchant fleet that employed Tenjiku Tokubei when he first set sail? Isn't it exciting to think about! (...) In 2004, a man named Kang Tae-jung from Jinju donated to the Jinju National Museum some old documents that had been passed down through his family, including a copy of the Jinju region's Hyangan, produced in 1634.

However, in this fragrance, there was one scholar who was recorded at a fairly high level, who had not taken the civil service examination.

Regarding this person, the database of the Korean Local Culture Encyclopedia explains, “Among the people listed in this book, Jo Wan-byeok, who was from Jinju, was captured during the Imjin War, and amassed a large sum of money in Southeast Asia and other places, is recorded as a Confucian scholar, which is noteworthy.”

--- pp.341-342

First of all, although the Dutch East India Company is very famous, it was not the first Dutch company to enter East Asia.

There were also Dutchmen who had reached the East Indies on Portuguese ships before him, such as Dirk 'Sina' Pomp.

And after the Revolutionary War began and it became impossible to board Portuguese or Spanish ships, between 1594 and 1602, before the Dutch East India Company was founded, companies called voorcompagnie flourished in the Netherlands.

At that time, companies would pool funds, prepare ships and cargo, go out to sea, exchange them for something more valuable, receive a share of the profits, and then disband. This was a form of corporate organization similar to today's project financing.

--- p.388

But the Dutch ships have some problems.

This means that powerful Catholic countries such as Portugal and Spain had already advanced into Japan and China.

England may be like that, but the Netherlands has a completely different meaning to these Iberian countries.

If the Japanese or Chinese authorities had said, "These are a rebel group that believes in a heretical cult (Protestantism) without a king or a country," they could have easily used facts to slander others.

No, I actually did that.

So, to alleviate this problem to some extent in the beginning, both the Porte Compagnie and the VOC set sail with a diplomatic letter stating that Prince Maurice of Orange, who was not actually the king but was the Stadtholder, was the 'King of Holland'.

--- p.392

There is an interesting record from Joseon in the late 18th century, about 40 years after this 『Hwangcheongjikgongdo』.

In fact, there are surprisingly many records of people drifting abroad during the Joseon Dynasty.

Among them, there are quite a few stories of people floating from Jeju Island or the southern coast to Nagasaki.

There are cases of people like Lee Ji-hang who floated to Hokkaido, although they are quite exceptional, and conversely, there are also records of people who floated as far away as Taiwan.

In 1796, during the reign of King Jeongjo, there was a man named Lee Bang-ik who drifted to Taiwan and returned. His account of his drift was reported to King Jeongjo, and was compiled into a piece of drift literature by Park Ji-won of Yeonam and passed down.

Here is an excerpt from the article titled “Seo Yi Bang-ik-sa.”

--- p.452

And the port permitted on the Japanese side was Nagasaki, a traditional foreign trade port.

The Edo shogunate originally implemented several policies to bring Nagasaki's foreign trade under its direct control.

In 1635, the Chinese, who had previously enjoyed more freedom, began to be controlled by centralizing them into Chinese-controlled areas called Tojin Yashiki.

However, as trade was permitted in China, Qing merchants naturally began to come to Nagasaki in earnest.

For example, records from 1688 indicate that nearly 10,000 Qing people sailed that year.

When it comes to Nagasaki, Dejima Island, where the Dutch stayed, is most famous, but in fact, through this Tojinyashiki, trade with China took place on a scale incomparable to that of the VOC.

To make a simple comparison, Dejima was said to be 9,000 square meters in size, while Tojinyashiki was 31,000 square meters.

--- pp.472-473

However, this book says that 'ginseng' is considered a very important prescription.

No, it is said that the actual prescription using ginseng first appeared in the 『Shang Han Lun』.

Although ginseng is so important, the problem is that ginseng does not grow natively in Japan.

Interestingly, the introduction of new information created a demand for ginseng, a commodity with no supply, which in turn drew Joseon into the flow of East Asian trade.

The now well-known triangular trade of Joseon in the 18th century is the triangular trade in which Joseon ginseng was sold through the Japanese embassy and the silver received in payment for the ginseng was sent to Beijing through the Joseon envoy and exchanged for silk.

The 18th century also marked the beginning of Joseon's social and economic stability and its re-entry into the international network.

I sometimes imagine the sight of the big-nosed, wide-eyed people sitting in the guest house on a long winter night, talking in their still-clumsy Korean about the cities of the Netherlands across the distant sea, the seas of India, the golden beaches of Africa, and the deep forests of New Amsterdam, and the topknot-haired Koreans listening to them, adding interjections.

--- p.12

As you can see from the original image, the name 'ㅎㆎㄴ듥쓥솎ㄴ' recorded here as the leader is written in Korean.

In the records of Yu Deuk-gong mentioned earlier, the name was written in Korean, that is, translated into Korean.

The text has something to say.

That's true.

In Jeju, there were still names written in Korean.

The leader was Hyeon-deung-yam-seon-n, and the craftsman who steers the ship was called Gi-ta-gong, or navigator. When Hyeon-deung-yam-seon-n was written in Chinese characters, it was transferred to Baek-gye-ya-eum-sa-eun.

Baekgye literally means ‘white chicken.’

Oh, then! Did you translate ㅎㆎㄴ듥 into white chicken?

--- pp.33-34

If you read it, you will notice that the worlds that Beltevrey and Hamel knew were subtly different from each other in this conversation.

Hamel had already said that the Dutch were trading with Japan on a regular basis, but Weltevree knew that Japan did not allow trade with foreign countries and that anyone who tried to go there would probably end up dead.

Hamel further reports that he felt that Beltevrey was actively trying to persuade him not to even think about returning.

With a twenty-year time difference between these two groups, aren't they perhaps Dutch people from entirely different parallel universes? What was happening beyond the blue seas of 17th-century Jeju Island?

--- p.55

Rukui began to spread new knowledge and beliefs enthusiastically through his network, and interested and responsive scholars began to seek out Matteo Ricci.

As I explained, Rukui was originally an insider in the Confucian scholar network in the Jiangnan region of China, and the more he learned from Matteo Ricci, the more he felt that it would be better to follow the Confucian approach rather than Buddhism, and that only then would he be able to enter the upper echelons of Chinese society.

And Matteo Ricci studied Chinese classics through his connections with Ming Dynasty scholars.

In the process, the existing approach of borrowing Buddhism from the Ruggieri style was gradually abandoned and a method of coexistence between Catholicism and Chinese Confucianism was considered.

--- p.123

Among the surviving Christians after Christianity was completely banned, there were those who hid their faith and lived in hiding.

These are the people who risked their lives to protect their faith and lived in hiding for 250 years, only to surprise the world by reappearing when Europeans returned to Japan in the late 19th century.

These people are called 'Kakure Kirishitan', meaning 'hidden Christians'.

Until the Edo shogunate stabilized and banned Catholicism in the early 17th century, the main Christian areas were Kyushu and Kyoto, and they were generally established in a significant part of western Japan.

In the early stages of oppression, it started with banishments and crackdowns, but gradually the level of prohibition became oppressive.

After the Shimabara Rebellion, arguably the worst of the crisis, was suppressed in the 1630s, Christianity in Japan appeared to have been virtually "eradicated."

--- p.134

Sometime between June 25 and 30, 1605, four years after the Catholic Church was established, a guest came to visit Matteo Ricci.

Matteo Ricci welcomed the old scholar guest, invited him inside, and then knelt before the statue and worshipped it.

Records show that there was a statue of John the Baptist, a statue of the Virgin Mary holding the baby Jesus, and statues of four saints surrounding it.

Then, this old Chinese scholar also followed Richie's example by kneeling and bowing down.

And a 60-year-old scholar who identified himself as Ngai, a native of Chafamfu (Kaifeng Prefecture, Hunan Province) and a Jinshi official, said that he had come up to Beijing from his hometown to take the exam for his doctorate, and upon reading an article about Westerners who had arrived and opened a temple, he came to see them, thinking that they might be of the same religion as him.

At first, Rich was surprised to hear that Ngai was a Christian, a group that had existed in China since the time of Kublai Khan, but what was even more surprising was that Ngai was an Israelite, that is, a Jew.

--- p.150

Of course, the Ming court did not initially encourage this flow of silver circulation and the practice of paying taxes or transactions with silver, but the existing paper money system was already severely devalued and the complex in-kind tax system could not support the Ming economic system, so around the end of the 1560s, a new tax system suggested by Zhang Juzheng was implemented, mainly in Jiangnan.

This new system is called the 'One Article Whip Law'.

In the West, it is called 'single whip tax reform' in English.

If I had to translate it, it would be something like "A tax revision that can be easily handled like a single whipping." At first, I wondered what that meant, but then I realized it was a direct translation of the "one-day tax bill."

To put it in a very simple version, he surveyed the land of China and applied all the complicated and difficult taxes in kind as land tax and poll tax, and had them paid in silver.

And regardless of whether you consider the traditional interpretation or the recent revisionist economic history interpretation, there is no great disagreement that this one-year policy was the catalyst for the flow of silver from all over the world into China for nearly four centuries.

So where did all that silver come from?

--- pp.197-198

With that in mind, let's look at the gold-silver ratio above.

Rather than bringing the silver produced in Potosi to Spain and distributing it in the European market, taking it to Manila and taking it to China, even after paying the various risks of the voyage, would yield roughly twice the profit mathematically.

In fact, Jan Huygen van Linschoten, who played a huge role in the Dutch expansion into the East Indies in the 17th century, wrote to his parents while working in Goa, India, in a letter, “From here in Goa, India to China or Japan is as far as from here to Lisbon. If I have 200 or 300 gold ducats now, it will be worth 600 or 700 ducats there.”

In fact, some studies suggest that this opportunity for profit drove the Spanish, Macau-Manila, Manila-Fujian, and Japan-Macau-Portugal lines into a madness of getting rich quick.

--- p.209

This is a true story about a young Joseon man who was captured by the Japanese army during the Imjin War, became a Christian, and finally became free. He went to the Philippines in 1617, where he was practicing his faith at a Rosary prayer meeting in Manila. He went to Joseon with the priests who had cared for him, crossed the rough South Seas to Nagasaki to spread the faith that had saved him, and braved hardships to finally return to Joseon.

This is not a novel.

Actually, I have not yet confirmed the Joseon side's records of this incident.

First of all, in 『Sillok』, 『Seungjeongwon Diary』, etc., I could not find any record of the repatriation of the son of a high-ranking official from Japan in 1618, the 10th year of King Gwanghae's reign.

However, in 1617, the second Joseon envoy, who was trying to normalize diplomatic relations with Japan and bring back the exhausted Joseon people, stayed in Japan for almost half a year, and brought back Joseon people who had survived the chaos and changed the country and had begun to settle in Japan.

The first exorcism took place in 1607, and the second exorcism occurred in 1617.

--- pp.243-244

And in Linthorton's book, 'Itinerary of Voyages', 'Korea' also appears.

After a long explanation of Japan, the description of Korea Island and Macau follows.

“Not far from the coast of Sina, at 34 and 356 degrees, slightly above the horizon, is a place called 'Insula de Core.'

There is a brief record that says, “Nothing is known about this island, neither its size nor its population nor its resources.”

This is currently known to be the first record describing Korea among the records of the Western European Age of Exploration.

The information about Korea mentioned in this 『Itinerary』 was not updated much even after 28 years, so Beltevrey, who had drifted ashore in Jeju, even knew that people were eaten in Korea.

--- p.315

After suppressing the Shimabara Rebellion, the Edo Bakufu began to exert full control over all of Japan.

As seen in Park Ji-won's article, the Edo shogunate even went so far as to request cooperation from Joseon to prevent any possible Christian uprising.

In 1712, nearly 70 years after the Shimabara Rebellion, the expulsion of Catholics and the Shimabara Rebellion were mentioned in the 『Overseas Reports』, a report on international affairs collected and submitted from Japan by Im Su-gan of the diplomatic mission in the year of Shinmyo.

(……) Here, the famous statue-stepping ‘Fumie’ is even mentioned.

In the end, it was a ritual to expose hidden Christians by making them step on the crucifix or the Virgin Mary statue. In Europe, it was famous as a symbol of Japan's anti-Christian culture, and an episode even appeared in Gulliver's Travels.

--- pp.326-327

But, you know.

What if there had been a Korean who had traveled to Southeast Asia as a clerk on the Nanban trading ship of the Suminokura merchant fleet that employed Tenjiku Tokubei when he first set sail? Isn't it exciting to think about! (...) In 2004, a man named Kang Tae-jung from Jinju donated to the Jinju National Museum some old documents that had been passed down through his family, including a copy of the Jinju region's Hyangan, produced in 1634.

However, in this fragrance, there was one scholar who was recorded at a fairly high level, who had not taken the civil service examination.

Regarding this person, the database of the Korean Local Culture Encyclopedia explains, “Among the people listed in this book, Jo Wan-byeok, who was from Jinju, was captured during the Imjin War, and amassed a large sum of money in Southeast Asia and other places, is recorded as a Confucian scholar, which is noteworthy.”

--- pp.341-342

First of all, although the Dutch East India Company is very famous, it was not the first Dutch company to enter East Asia.

There were also Dutchmen who had reached the East Indies on Portuguese ships before him, such as Dirk 'Sina' Pomp.

And after the Revolutionary War began and it became impossible to board Portuguese or Spanish ships, between 1594 and 1602, before the Dutch East India Company was founded, companies called voorcompagnie flourished in the Netherlands.

At that time, companies would pool funds, prepare ships and cargo, go out to sea, exchange them for something more valuable, receive a share of the profits, and then disband. This was a form of corporate organization similar to today's project financing.

--- p.388

But the Dutch ships have some problems.

This means that powerful Catholic countries such as Portugal and Spain had already advanced into Japan and China.

England may be like that, but the Netherlands has a completely different meaning to these Iberian countries.

If the Japanese or Chinese authorities had said, "These are a rebel group that believes in a heretical cult (Protestantism) without a king or a country," they could have easily used facts to slander others.

No, I actually did that.

So, to alleviate this problem to some extent in the beginning, both the Porte Compagnie and the VOC set sail with a diplomatic letter stating that Prince Maurice of Orange, who was not actually the king but was the Stadtholder, was the 'King of Holland'.

--- p.392

There is an interesting record from Joseon in the late 18th century, about 40 years after this 『Hwangcheongjikgongdo』.

In fact, there are surprisingly many records of people drifting abroad during the Joseon Dynasty.

Among them, there are quite a few stories of people floating from Jeju Island or the southern coast to Nagasaki.

There are cases of people like Lee Ji-hang who floated to Hokkaido, although they are quite exceptional, and conversely, there are also records of people who floated as far away as Taiwan.

In 1796, during the reign of King Jeongjo, there was a man named Lee Bang-ik who drifted to Taiwan and returned. His account of his drift was reported to King Jeongjo, and was compiled into a piece of drift literature by Park Ji-won of Yeonam and passed down.

Here is an excerpt from the article titled “Seo Yi Bang-ik-sa.”

--- p.452

And the port permitted on the Japanese side was Nagasaki, a traditional foreign trade port.

The Edo shogunate originally implemented several policies to bring Nagasaki's foreign trade under its direct control.

In 1635, the Chinese, who had previously enjoyed more freedom, began to be controlled by centralizing them into Chinese-controlled areas called Tojin Yashiki.

However, as trade was permitted in China, Qing merchants naturally began to come to Nagasaki in earnest.

For example, records from 1688 indicate that nearly 10,000 Qing people sailed that year.

When it comes to Nagasaki, Dejima Island, where the Dutch stayed, is most famous, but in fact, through this Tojinyashiki, trade with China took place on a scale incomparable to that of the VOC.

To make a simple comparison, Dejima was said to be 9,000 square meters in size, while Tojinyashiki was 31,000 square meters.

--- pp.472-473

However, this book says that 'ginseng' is considered a very important prescription.

No, it is said that the actual prescription using ginseng first appeared in the 『Shang Han Lun』.

Although ginseng is so important, the problem is that ginseng does not grow natively in Japan.

Interestingly, the introduction of new information created a demand for ginseng, a commodity with no supply, which in turn drew Joseon into the flow of East Asian trade.

The now well-known triangular trade of Joseon in the 18th century is the triangular trade in which Joseon ginseng was sold through the Japanese embassy and the silver received in payment for the ginseng was sent to Beijing through the Joseon envoy and exchanged for silk.

The 18th century also marked the beginning of Joseon's social and economic stability and its re-entry into the international network.

--- pp.475-476

Publisher's Review

Three key words of this book

This book reconstructs the 17th-century East Asian sea through three keywords.

First, the 'Navigator's White Chicken' symbolizes the Europeans who traveled the world through the sea.

It tells the story of how the name 'white chicken' came to be, starting with the arrival of Europeans in East Asia.

The word 'Padre' refers to a Catholic missionary who came to East Asia and risked his life to spread the faith, whom we call 'priest'.

We will tell you how these people came to the other side of the world with the Portuguese and Spanish, who were called the Nanman.

The final 'Orange Rebels' is a keyword that tells the story of the intertwined groups of Europeans who came to East Asia in the early modern period.

It describes how the Dutch, a people from the "low lands," challenged the order of the Portuguese and Spanish empires that divided the world's oceans in two at the time and took steps that changed the course of East Asian and world history.

The colorful historical events that vividly portray the encounter between early modern East Asia and Europe, along with background explanations that provide a comprehensive overview, will be useful information for readers interested in early modern East Asian history during the Age of Exploration.

If we read the story of East Asia not only in the context of East Asia but also from a broader perspective, we can see the story of Joseon, or even our own story, in a complex way.

What happened in Joseon during that time?

It is only natural that 17th century Joseon cannot be left out of the network of this story.

The appearance of Hamel and his crew, who had drifted ashore on the coast of Seogwipo, Jeju Island in 1653, was a significant moment in Joseon's incorporation into the turbulent world history in which East Asia and Europe were intricately intertwined.

This book presents the complex landscape of East Asia on the threshold of modernity through not only Hamel but also various people and events that were crossroads of world history at the time.

This book introduces some very interesting stories, especially for those of us who have only lamented the closed nature of Joseon at the time.

A representative example is Thomas, a young Joseon man who was captured by the Japanese army during the Imjin War, became a Christian, and finally became free, went to the Philippines, where he practiced his faith at the Rosary prayer meeting in Manila in 1617.

Although it ended up being a one-time episode unrelated to the later Joseon Catholic Church, the book 『History of the Rosary Missionary Diocese in the Philippines, Japan and China』 from 1640, which deals with the missionary history of the Rosary Order of the Dominican Friars in Manila, Philippines, states that after nearly ten years, the son, upon hearing that Joseon envoys in Japan, who had received a request from his father, were looking for him, returned to Joseon with the priests to spread the faith that had saved him.

There is also a scholar who is recorded in a copy of the Hyangan of the Jinju region produced in 1634.

Regarding this person, the database of the 『Encyclopedia of Korean Local Culture』 contains an explanation that “Among the people listed in this book, Jo Wan-byeok, who was from Jinju, was taken prisoner during the Imjin War, and amassed a large sum of money in Southeast Asia and other places, is recorded as a Confucian scholar, which is noteworthy.”

Although Seo Saeng Jo Wan-byeok is not well known today, to the point where you might wonder if such a person existed, he was a fairly well-known figure among Joseon scholars from the early 17th century to the 18th century.

Because he was the first person to visit Vietnam and introduce the local Korean Wave boom.

According to the “Biography of Jo Wan-byeok” in Jibong Lee Su-gwang’s “Jibongjip” and Maechang Jeong Sa-sin’s “Maechang Seonsaengjip,” Seo-saeng Jo Wan-byeok boarded the Suminokura merchant ship in Kyoto, traveled around Vietnam, the Philippines, and the southeastern sea of Okinawa, amassed a fortune, and returned to his hometown of Jinju.

The story that began in 1657, when they were trying to survive the harsh winter of Gangjin and get food, returns to the other side of the world and continues with the flags of Tartar, the port of Nangasaki, the forests of Taiaoan, and the taste of herring eaten in Gangjin.

All the people featured here operated at the boundaries of different languages, cultures, and thought systems.

They may not have known it at the time, but they each had their own circumstances, and although they may not have known it at the time, there is a history that was created because of them.

A unique genre that stretches from microhistory to world history

Author Dylan Yu was born in Korea and, like the characters in this book, crossed the ocean and settled in New York. Like his life story, he freely crosses borders and eras, and has written on the Igloos blog 'Dylan Yu's Thoughts' from 2007 to 2023, focusing especially on economic history, modern history of science, modern history of East-West exchange, and modern cultural history.

And this book, based on a meticulous analysis of vast knowledge and data, crosses the encounter between Europe and East Asia during the Age of Exploration, revealing the stories of those who ushered in the modern era through the grand global currents hidden within small incidents.

Just as Hamel's drift became a bridge connecting Joseon and Europe, a single scene from everyday life can have a butterfly effect that changes the course of world history.

Adrift on the coast of Joseon, a missionary's adventure, the choice of the Orange Rebels… … .

These events are not mere historical episodes, but come to life as vivid stories of people who are connected to our history through the people who crossed the sea.

This is an interesting work, infused with the author's desire to share with readers the principles and processes of history, which interact and influence one another within a complex and multi-layered network of relationships, through intriguing subject matter and captivating writing style.

The author's idea that it is neither possible nor desirable to perceive history as separate from one's own history and that of others is further highlighted through the background explanation of this intense and inter-civilizational exchange, which is often intertwined, and the colorful historical events that are viewed within the context of world history.

This book reconstructs the 17th-century East Asian sea through three keywords.

First, the 'Navigator's White Chicken' symbolizes the Europeans who traveled the world through the sea.

It tells the story of how the name 'white chicken' came to be, starting with the arrival of Europeans in East Asia.

The word 'Padre' refers to a Catholic missionary who came to East Asia and risked his life to spread the faith, whom we call 'priest'.

We will tell you how these people came to the other side of the world with the Portuguese and Spanish, who were called the Nanman.

The final 'Orange Rebels' is a keyword that tells the story of the intertwined groups of Europeans who came to East Asia in the early modern period.

It describes how the Dutch, a people from the "low lands," challenged the order of the Portuguese and Spanish empires that divided the world's oceans in two at the time and took steps that changed the course of East Asian and world history.

The colorful historical events that vividly portray the encounter between early modern East Asia and Europe, along with background explanations that provide a comprehensive overview, will be useful information for readers interested in early modern East Asian history during the Age of Exploration.

If we read the story of East Asia not only in the context of East Asia but also from a broader perspective, we can see the story of Joseon, or even our own story, in a complex way.

What happened in Joseon during that time?

It is only natural that 17th century Joseon cannot be left out of the network of this story.

The appearance of Hamel and his crew, who had drifted ashore on the coast of Seogwipo, Jeju Island in 1653, was a significant moment in Joseon's incorporation into the turbulent world history in which East Asia and Europe were intricately intertwined.

This book presents the complex landscape of East Asia on the threshold of modernity through not only Hamel but also various people and events that were crossroads of world history at the time.

This book introduces some very interesting stories, especially for those of us who have only lamented the closed nature of Joseon at the time.

A representative example is Thomas, a young Joseon man who was captured by the Japanese army during the Imjin War, became a Christian, and finally became free, went to the Philippines, where he practiced his faith at the Rosary prayer meeting in Manila in 1617.

Although it ended up being a one-time episode unrelated to the later Joseon Catholic Church, the book 『History of the Rosary Missionary Diocese in the Philippines, Japan and China』 from 1640, which deals with the missionary history of the Rosary Order of the Dominican Friars in Manila, Philippines, states that after nearly ten years, the son, upon hearing that Joseon envoys in Japan, who had received a request from his father, were looking for him, returned to Joseon with the priests to spread the faith that had saved him.

There is also a scholar who is recorded in a copy of the Hyangan of the Jinju region produced in 1634.

Regarding this person, the database of the 『Encyclopedia of Korean Local Culture』 contains an explanation that “Among the people listed in this book, Jo Wan-byeok, who was from Jinju, was taken prisoner during the Imjin War, and amassed a large sum of money in Southeast Asia and other places, is recorded as a Confucian scholar, which is noteworthy.”

Although Seo Saeng Jo Wan-byeok is not well known today, to the point where you might wonder if such a person existed, he was a fairly well-known figure among Joseon scholars from the early 17th century to the 18th century.

Because he was the first person to visit Vietnam and introduce the local Korean Wave boom.

According to the “Biography of Jo Wan-byeok” in Jibong Lee Su-gwang’s “Jibongjip” and Maechang Jeong Sa-sin’s “Maechang Seonsaengjip,” Seo-saeng Jo Wan-byeok boarded the Suminokura merchant ship in Kyoto, traveled around Vietnam, the Philippines, and the southeastern sea of Okinawa, amassed a fortune, and returned to his hometown of Jinju.

The story that began in 1657, when they were trying to survive the harsh winter of Gangjin and get food, returns to the other side of the world and continues with the flags of Tartar, the port of Nangasaki, the forests of Taiaoan, and the taste of herring eaten in Gangjin.

All the people featured here operated at the boundaries of different languages, cultures, and thought systems.

They may not have known it at the time, but they each had their own circumstances, and although they may not have known it at the time, there is a history that was created because of them.

A unique genre that stretches from microhistory to world history

Author Dylan Yu was born in Korea and, like the characters in this book, crossed the ocean and settled in New York. Like his life story, he freely crosses borders and eras, and has written on the Igloos blog 'Dylan Yu's Thoughts' from 2007 to 2023, focusing especially on economic history, modern history of science, modern history of East-West exchange, and modern cultural history.

And this book, based on a meticulous analysis of vast knowledge and data, crosses the encounter between Europe and East Asia during the Age of Exploration, revealing the stories of those who ushered in the modern era through the grand global currents hidden within small incidents.

Just as Hamel's drift became a bridge connecting Joseon and Europe, a single scene from everyday life can have a butterfly effect that changes the course of world history.

Adrift on the coast of Joseon, a missionary's adventure, the choice of the Orange Rebels… … .

These events are not mere historical episodes, but come to life as vivid stories of people who are connected to our history through the people who crossed the sea.

This is an interesting work, infused with the author's desire to share with readers the principles and processes of history, which interact and influence one another within a complex and multi-layered network of relationships, through intriguing subject matter and captivating writing style.

The author's idea that it is neither possible nor desirable to perceive history as separate from one's own history and that of others is further highlighted through the background explanation of this intense and inter-civilizational exchange, which is often intertwined, and the colorful historical events that are viewed within the context of world history.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: November 10, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 568 pages | 768g | 145*220*27mm

- ISBN13: 9788964622148

- ISBN10: 8964622146

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)