Address Story

|

Description

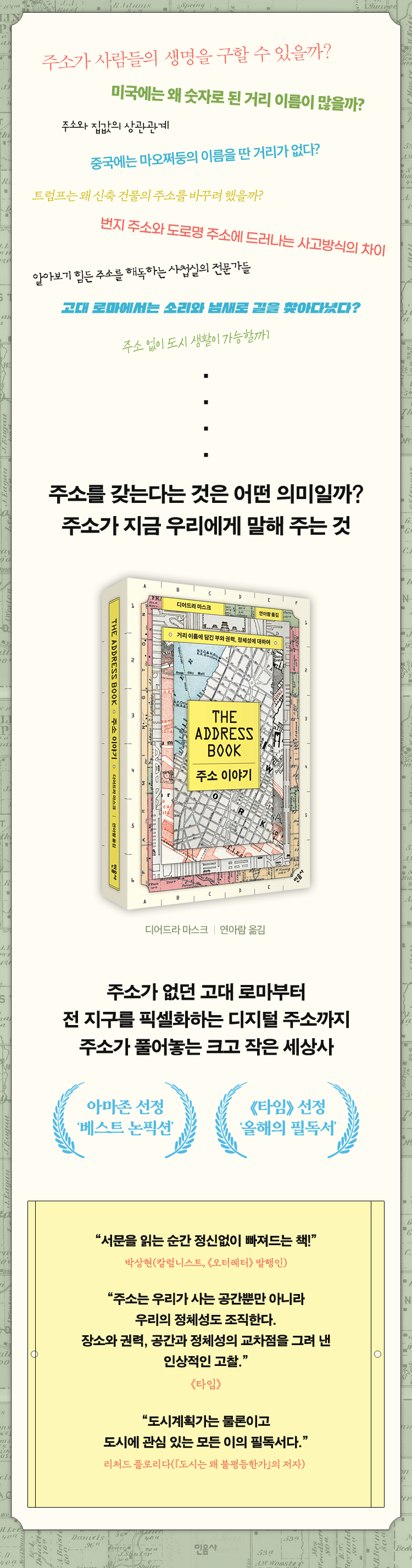

Book Introduction

[Time] Must-Read Books of the Year

“A book that will have you hooked the moment you read the introduction!”

Park Sang-hyun (columnist, publisher of [Otter Letter])

From urban planning to real estate, school districts, voting, opening bank accounts, and tracking infectious diseases.

Forming the framework of human life and community

A fascinating journey exploring the world of addresses

Minumsa has published "Address Stories," which explores the origins and history of addresses and explores the various socio-political issues contained in address systems and street names.

Author Deirdre Mask vividly portrays colorful stories about addresses by reporting and interviewing cases not only across the United States but also across Europe, including England, Germany, and Austria, as well as Korea, Japan, India, Haiti, and South Africa.

In addition, we look into the future of addresses, which will change with the emergence of digital addresses such as Wat3Rewards and Google Plus Code.

This book explores the intersection of place and power, space and identity, unraveling the surprising history and meaning contained in seemingly ordinary addresses.

“A book that will have you hooked the moment you read the introduction!”

Park Sang-hyun (columnist, publisher of [Otter Letter])

From urban planning to real estate, school districts, voting, opening bank accounts, and tracking infectious diseases.

Forming the framework of human life and community

A fascinating journey exploring the world of addresses

Minumsa has published "Address Stories," which explores the origins and history of addresses and explores the various socio-political issues contained in address systems and street names.

Author Deirdre Mask vividly portrays colorful stories about addresses by reporting and interviewing cases not only across the United States but also across Europe, including England, Germany, and Austria, as well as Korea, Japan, India, Haiti, and South Africa.

In addition, we look into the future of addresses, which will change with the emergence of digital addresses such as Wat3Rewards and Google Plus Code.

This book explores the intersection of place and power, space and identity, unraveling the surprising history and meaning contained in seemingly ordinary addresses.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Introduction: Why is the address important? 11

development

1 Kolkata: How Addresses Transform Slums? 35

2 Haiti: Can Addresses Stop the Pandemic? 65

genesis

3 Rome: How Did the Ancient Romans Find Their Way? 99

4 London: How Are Street Names Created? 119

5 Bin: Address is Power 149

6 Philadelphia: Why Are There So Many Numbered Street Names in the US? 178

7 Korea and Japan: Differences Between Street Addresses and Street Number Addresses 207

politics

8 Iran: Why Do Street Names Change After the Revolution? 227

9 Berlin: Overcoming Germany's Past as Revealed by Nazi-Era Street Names 252

human race

10 Hollywood, Florida: Those Who Want to Protect Street Names, Those Who Want to Change Them 277

11 St. Louis: Martin Luther King Street: America's Race Problem 301

12 South Africa: Who Owns the Street Names? 320

class and status

13 New York Manhattan: How Much Is an Address Worth? 355

14 Homelessness: Can You Live Without an Address? 382

Going Out: The Future of Address 403

Acknowledgments 427

Week 431

development

1 Kolkata: How Addresses Transform Slums? 35

2 Haiti: Can Addresses Stop the Pandemic? 65

genesis

3 Rome: How Did the Ancient Romans Find Their Way? 99

4 London: How Are Street Names Created? 119

5 Bin: Address is Power 149

6 Philadelphia: Why Are There So Many Numbered Street Names in the US? 178

7 Korea and Japan: Differences Between Street Addresses and Street Number Addresses 207

politics

8 Iran: Why Do Street Names Change After the Revolution? 227

9 Berlin: Overcoming Germany's Past as Revealed by Nazi-Era Street Names 252

human race

10 Hollywood, Florida: Those Who Want to Protect Street Names, Those Who Want to Change Them 277

11 St. Louis: Martin Luther King Street: America's Race Problem 301

12 South Africa: Who Owns the Street Names? 320

class and status

13 New York Manhattan: How Much Is an Address Worth? 355

14 Homelessness: Can You Live Without an Address? 382

Going Out: The Future of Address 403

Acknowledgments 427

Week 431

Detailed image

Into the book

Addresses aren't just for emergency rescue.

Addresses exist to locate and monitor people, to impose taxes, and to sell people things they don't really need through the mail.

West Virginians who look askance at the address business bear a striking resemblance to 18th-century Europeans who resisted the government putting numbers on their doors.

But many residents knew what a benefit it would be to be able to find their homes on Google Maps.

Like the 18th-century Europeans who eventually fell in love with the delightful thud of mail falling through a hole in their door.

---From "Introduction: Why is the address important?"

The slums of Kolkata seemed to have more pressing issues than addresses.

There was no sanitation, clean water, or medical services, and there was no roof to protect against the monsoon rains.

But they had no address and had no chance to leave the slums.

Without an address, you usually can't open a bank account.

Without a bank account, you can't save, get a loan, or receive a pension.

Most importantly, your address is essential to proving your identity.

All Indian residents are required to have an Aadhaar card, a government-issued biometric identity document, but slum dwellers often have difficulty obtaining one because they do not have an address.

Without this card, which has a twelve-digit personal identification number, you will be unable to access most public services such as childbirth support, pensions, and higher education.

You can't even get food assistance.

Activists say people across India are starving to death because they don't have Aadhaar cards.

---From "Chapter 1 Kolkata: How Addresses Transform Slums"

When a cholera outbreak broke out in London's Soho in 1854, the disease spread very quickly.

Fortunately, Britain was going through a period of new transformation at the time.

In 1837, the General Register Office was established to record the births and deaths of the people.

William Parr, who was in charge of organizing new data at the Registrar's Office, was a medical school graduate.

He was obsessed with how British people lived and died, collecting data on causes of death and occupations.

For the first time, it became clear how people die in London.

I knew very well that if you don't know how people die, you can't study why they die.

These detailed statistics were possible thanks to road name addresses.

London has been meticulously mapped for a long time, but assigning house numbers to each house is a fairly recent development.

In 1765, the British Parliament ordered that all houses be numbered and the numbers be prominently displayed on the doors.

Thanks to this, the National Registry Office was able to determine not only who had died but also where the deaths occurred.

Knowing where deaths occurred is undoubtedly important information for public health.

In this way, it became possible to accurately locate the location of the outbreak area through the address.

---From "Chapter 2 Haiti: Can Addresses Stop the Epidemic?"

London has long lacked a central authority to name its streets, so the job has been left to private firms, often with limited imagination.

“In 1853, London had 25 Albert Streets, 25 Victoria Streets, 37 King Streets, 27 Queen Streets, 22 Princess Streets, 17 Duke Streets, 34 York Streets, and 23 Gloucester Streets.

Even this excludes similar names, that is, those with words other than street after the name (place, road, square, court, alley, mew).”

A few years later, in 1869, the famous British magazine The Spectator asked its readers this question:

“Are you saying that all the builders name their streets after their wives, sons, and daughters?” Other street names were taken from all sorts of fruits and flowers that we could think of in five minutes.

The most pathetic of these was 'New Street', of which there were a whopping 52 streets.

---From "Chapter 4 London: How Were Street Names Created?"

Even the official street names provide more information than you might think.

Daniel Ottoferalías, an economist who studied street names in Spain and the UK, found that in Spain, people who lived in areas with more religious street names were actually more religious.

In England, people living in areas with more street names containing the word "church" or "chapel" were more likely to identify as Christian, while in Scotland, people living on streets with names like "London Road" or "Royal Street" were found to have a weaker Scottish identity.

The causal relationship between these two is not clearly known.

Perhaps you live on Church Street because you want to live near a church because of your deep religious beliefs, or perhaps living on Church Street has deepened your religious beliefs.

Road names are created by humans, but humans can also change according to road names.

---From "Chapter 4 London: How Were Street Names Created?"

Even today, Western tourists visiting Tokyo find the lack of street names particularly perplexing (only a few major thoroughfares are). Instead of naming streets, Tokyo numbers blocks.

The road is just the space between the blocks.

Most buildings are also numbered, but they are numbered according to the order in which they were built, not their location.

Shelton, an urban planner, analyzed the differences in writing systems in relation to the way Westerners and Japanese view cities.

People who learned English were taught to see the good.

So Westerners have been fixated on roads (lines) and have insisted on the practice of naming roads.

In contrast, Japan focuses more on regions, or blocks.

The integrated urban planning seen in places like New York or Paris is not part of the Japanese way of thinking.

---From "Chapter 7 Korea and Japan: Differences between Road Name Addresses and Street Addresses"

Pierre Nora, who studied collective memory in France, argued that until the 19th century, humans did not use objects to remember the past.

Because the memories were deeply rooted in local culture, habits, and customs.

However, as society changed rapidly in the 20th century, the pace of history accelerated, and memories gradually disappeared from everyday experience, humans began to feel a strong desire to preserve memories not only in their heads but also in special objects or places, such as monuments or street names.

Humans want life to be predictable, and for that to happen, we need a “narrative link” between the present and the past, a reassurance that everything is going well.

So, humans try to force the future society to look like the past by collecting memories, erecting statues in parks, and engraving them as street names.

So, commemorating the past is just another wish for the present.

The problem is that we don't always share the same memories.

The opportunity to preserve collective memory by engraving it on geographic features is not given equally to everyone.

As novelist Milan Kundera said, “The only reason why man wants to become the master of the future is because he wants to change the past.”

---From "Chapter 10 Hollywood, Florida: Those Who Want to Protect Street Names, Those Who Want to Change Them"

The address of the enormous new building built by the Zeckendorf brothers was 520 Park Avenue, but the main entrance of the building was not even on Park Avenue.

The actual location of the building was East 60th Street, 45 meters west of Park Avenue.

How is this possible?

In New York, you can even buy and sell addresses.

New York City is selling developers a special $11,000 per application to change their building's address to an attractive one.

New York City's self-described "meaningless address" program is an unusually candid admission that addresses can be sold to the highest bidder.

While some foreign buyers are fooled by "meaningless addresses," there are still many people in New York willing to pay high prices just for the address, even when they know the actual building isn't on Park Avenue.

---From "Chapter 13: Manhattan, New York: How Much Is an Address Worth?"

Trump's real estate development company asked the city to change the building's address from "15 Columbus Circle" to "1 Central Park West." (Columbus Circle was notorious for its traffic at the time.) The Trump company advertised the apartment as having "the most prestigious address in the world."

Trump knew that addresses were his most effective marketing tool.

The new building at 1 Central Park West has helped Trump solidify his position in New York's ultra-luxury apartment market, which has been at an all-time high for the past decade.

Addresses exist to locate and monitor people, to impose taxes, and to sell people things they don't really need through the mail.

West Virginians who look askance at the address business bear a striking resemblance to 18th-century Europeans who resisted the government putting numbers on their doors.

But many residents knew what a benefit it would be to be able to find their homes on Google Maps.

Like the 18th-century Europeans who eventually fell in love with the delightful thud of mail falling through a hole in their door.

---From "Introduction: Why is the address important?"

The slums of Kolkata seemed to have more pressing issues than addresses.

There was no sanitation, clean water, or medical services, and there was no roof to protect against the monsoon rains.

But they had no address and had no chance to leave the slums.

Without an address, you usually can't open a bank account.

Without a bank account, you can't save, get a loan, or receive a pension.

Most importantly, your address is essential to proving your identity.

All Indian residents are required to have an Aadhaar card, a government-issued biometric identity document, but slum dwellers often have difficulty obtaining one because they do not have an address.

Without this card, which has a twelve-digit personal identification number, you will be unable to access most public services such as childbirth support, pensions, and higher education.

You can't even get food assistance.

Activists say people across India are starving to death because they don't have Aadhaar cards.

---From "Chapter 1 Kolkata: How Addresses Transform Slums"

When a cholera outbreak broke out in London's Soho in 1854, the disease spread very quickly.

Fortunately, Britain was going through a period of new transformation at the time.

In 1837, the General Register Office was established to record the births and deaths of the people.

William Parr, who was in charge of organizing new data at the Registrar's Office, was a medical school graduate.

He was obsessed with how British people lived and died, collecting data on causes of death and occupations.

For the first time, it became clear how people die in London.

I knew very well that if you don't know how people die, you can't study why they die.

These detailed statistics were possible thanks to road name addresses.

London has been meticulously mapped for a long time, but assigning house numbers to each house is a fairly recent development.

In 1765, the British Parliament ordered that all houses be numbered and the numbers be prominently displayed on the doors.

Thanks to this, the National Registry Office was able to determine not only who had died but also where the deaths occurred.

Knowing where deaths occurred is undoubtedly important information for public health.

In this way, it became possible to accurately locate the location of the outbreak area through the address.

---From "Chapter 2 Haiti: Can Addresses Stop the Epidemic?"

London has long lacked a central authority to name its streets, so the job has been left to private firms, often with limited imagination.

“In 1853, London had 25 Albert Streets, 25 Victoria Streets, 37 King Streets, 27 Queen Streets, 22 Princess Streets, 17 Duke Streets, 34 York Streets, and 23 Gloucester Streets.

Even this excludes similar names, that is, those with words other than street after the name (place, road, square, court, alley, mew).”

A few years later, in 1869, the famous British magazine The Spectator asked its readers this question:

“Are you saying that all the builders name their streets after their wives, sons, and daughters?” Other street names were taken from all sorts of fruits and flowers that we could think of in five minutes.

The most pathetic of these was 'New Street', of which there were a whopping 52 streets.

---From "Chapter 4 London: How Were Street Names Created?"

Even the official street names provide more information than you might think.

Daniel Ottoferalías, an economist who studied street names in Spain and the UK, found that in Spain, people who lived in areas with more religious street names were actually more religious.

In England, people living in areas with more street names containing the word "church" or "chapel" were more likely to identify as Christian, while in Scotland, people living on streets with names like "London Road" or "Royal Street" were found to have a weaker Scottish identity.

The causal relationship between these two is not clearly known.

Perhaps you live on Church Street because you want to live near a church because of your deep religious beliefs, or perhaps living on Church Street has deepened your religious beliefs.

Road names are created by humans, but humans can also change according to road names.

---From "Chapter 4 London: How Were Street Names Created?"

Even today, Western tourists visiting Tokyo find the lack of street names particularly perplexing (only a few major thoroughfares are). Instead of naming streets, Tokyo numbers blocks.

The road is just the space between the blocks.

Most buildings are also numbered, but they are numbered according to the order in which they were built, not their location.

Shelton, an urban planner, analyzed the differences in writing systems in relation to the way Westerners and Japanese view cities.

People who learned English were taught to see the good.

So Westerners have been fixated on roads (lines) and have insisted on the practice of naming roads.

In contrast, Japan focuses more on regions, or blocks.

The integrated urban planning seen in places like New York or Paris is not part of the Japanese way of thinking.

---From "Chapter 7 Korea and Japan: Differences between Road Name Addresses and Street Addresses"

Pierre Nora, who studied collective memory in France, argued that until the 19th century, humans did not use objects to remember the past.

Because the memories were deeply rooted in local culture, habits, and customs.

However, as society changed rapidly in the 20th century, the pace of history accelerated, and memories gradually disappeared from everyday experience, humans began to feel a strong desire to preserve memories not only in their heads but also in special objects or places, such as monuments or street names.

Humans want life to be predictable, and for that to happen, we need a “narrative link” between the present and the past, a reassurance that everything is going well.

So, humans try to force the future society to look like the past by collecting memories, erecting statues in parks, and engraving them as street names.

So, commemorating the past is just another wish for the present.

The problem is that we don't always share the same memories.

The opportunity to preserve collective memory by engraving it on geographic features is not given equally to everyone.

As novelist Milan Kundera said, “The only reason why man wants to become the master of the future is because he wants to change the past.”

---From "Chapter 10 Hollywood, Florida: Those Who Want to Protect Street Names, Those Who Want to Change Them"

The address of the enormous new building built by the Zeckendorf brothers was 520 Park Avenue, but the main entrance of the building was not even on Park Avenue.

The actual location of the building was East 60th Street, 45 meters west of Park Avenue.

How is this possible?

In New York, you can even buy and sell addresses.

New York City is selling developers a special $11,000 per application to change their building's address to an attractive one.

New York City's self-described "meaningless address" program is an unusually candid admission that addresses can be sold to the highest bidder.

While some foreign buyers are fooled by "meaningless addresses," there are still many people in New York willing to pay high prices just for the address, even when they know the actual building isn't on Park Avenue.

---From "Chapter 13: Manhattan, New York: How Much Is an Address Worth?"

Trump's real estate development company asked the city to change the building's address from "15 Columbus Circle" to "1 Central Park West." (Columbus Circle was notorious for its traffic at the time.) The Trump company advertised the apartment as having "the most prestigious address in the world."

Trump knew that addresses were his most effective marketing tool.

The new building at 1 Central Park West has helped Trump solidify his position in New York's ultra-luxury apartment market, which has been at an all-time high for the past decade.

---From "Chapter 13: Manhattan, New York: How Much Is an Address Worth?"

Publisher's Review

What are cities made of?

Address, an essential element of complex city life

How did people find their way around in a time without addresses or maps? The ancient Romans had no trouble getting where they wanted, even without street names or house numbers.

Most people could imagine the space within the scope of their experience and experience, and they used their hearing and sense of smell to navigate the alleyways filled with all sorts of sounds and smells.

The scope of the space in my head was so small that I could ask and answer directions in the form of, 'If you go up the hill that you see from the market entrance, there is a temple. If you follow the alley with the fig tree right next to the temple, you will see the temple of Diana. Then, turn right there' (Terrence's play "The Brothers").

However, as civilization developed and society became more complex, the emergence of addresses became inevitable.

It became necessary to more systematically organize the space we live in, so that all participants in a conversation could point to places they had never been before, or to send letters and items to the correct places.

Moreover, naturally occurring street names tend to be duplicated as the city expands, so a means of reducing confusion was desperately needed.

In major cities around the world, including Paris, Berlin, Vienna, London, and New York, they began to put house numbers on every house.

In 1770, Maria Theresa of Austria issued an order to number each house, identify its inhabitants, and conscript 'soldiers' who could fight in the war.

In 19th century London, a large-scale road name reorganization project was carried out along with the postal system reform, and street numbers became established as standardized addresses.

Because American cities were established relatively recently, addresses were introduced systematically (this explains why many streets in the United States have numbered names).

When we think of 'urban planning', we often think of visible facilities such as road maintenance, new buildings, and public land for citizens.

But cities “need to be organized before they can be beautified.” While urban renewal and beautification projects affect only some areas or residents, a simple, efficient address system benefits people from all walks of life across the city.

Modern, complex urban life is made possible by the people who dedicated themselves to organizing the invisible infrastructure of the address system.

Does where I live tell anything about me?

The political economy of addresses that assign value to space

An address is not simply a means of specifying a location.

Even adjacent land changes value the moment it is incorporated into different administrative districts.

Research has shown that in the UK, houses or buildings on a 'street' sell for half the price of those on a 'lane', and in the US, houses with an address that includes 'lake' are worth 16 percent more than the median overall house price.

In Victoria, Australia, a study found that property prices on streets with vulgar or humorous names were 20 percent lower than those on other streets.

In New York, where real estate prices in the heart of the city are out of this world, you can even buy and sell an official address.

This is because city authorities sell address change application tickets.

Developers, including Donald Trump, have long recognized that addresses are powerful marketing tools, and have often tried to boost property value by attaching "expensive" addresses, such as those near Central Park, to their buildings.

The situation seems similar in Korea, where economic interests such as real estate and school districts are closely linked to one's address.

Because of the symbolic value of addresses, debates surrounding address revisions occur frequently around the world.

The question of what to commemorate and what not to commemorate is deeply imbued with the political, religious, and historical values of society's members.

This is also the reason why address changes follow revolutions or major events.

In this way, address revision is a microcosm of conflict and a battlefield of memories, but it also serves as a trigger for overcoming mistakes and driving social change.

Like efforts to change addresses built during the Nazi era, or addresses bearing the names of people who supported or defended slavery or apartheid.

Street names are a question of identity and wealth, and they are also a question of race.

Ultimately, it's all about power.

The power to name names, to make history, to decide who is important and who is not, and why.

Some books tell the story of how small objects like pencils and toothpicks changed the world.

This book is not that kind of book.

Rather, it is a complex story about how the enlightenment project of naming and numbering roads became a revolution that transformed human life and society.

- In the text

Over the years, addresses have become a symbol of our identity, a means by which governments exert power, and a way to reflect and improve the structure of society.

Even now, when the significance of living space is highlighted more than ever due to the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic, and even in a future where online spaces will occupy an even greater portion of our lives, the fundamental question of "Where am I?" will remain.

"Address Story" is a book that will serve as an interesting compass for these concerns.

Address, an essential element of complex city life

How did people find their way around in a time without addresses or maps? The ancient Romans had no trouble getting where they wanted, even without street names or house numbers.

Most people could imagine the space within the scope of their experience and experience, and they used their hearing and sense of smell to navigate the alleyways filled with all sorts of sounds and smells.

The scope of the space in my head was so small that I could ask and answer directions in the form of, 'If you go up the hill that you see from the market entrance, there is a temple. If you follow the alley with the fig tree right next to the temple, you will see the temple of Diana. Then, turn right there' (Terrence's play "The Brothers").

However, as civilization developed and society became more complex, the emergence of addresses became inevitable.

It became necessary to more systematically organize the space we live in, so that all participants in a conversation could point to places they had never been before, or to send letters and items to the correct places.

Moreover, naturally occurring street names tend to be duplicated as the city expands, so a means of reducing confusion was desperately needed.

In major cities around the world, including Paris, Berlin, Vienna, London, and New York, they began to put house numbers on every house.

In 1770, Maria Theresa of Austria issued an order to number each house, identify its inhabitants, and conscript 'soldiers' who could fight in the war.

In 19th century London, a large-scale road name reorganization project was carried out along with the postal system reform, and street numbers became established as standardized addresses.

Because American cities were established relatively recently, addresses were introduced systematically (this explains why many streets in the United States have numbered names).

When we think of 'urban planning', we often think of visible facilities such as road maintenance, new buildings, and public land for citizens.

But cities “need to be organized before they can be beautified.” While urban renewal and beautification projects affect only some areas or residents, a simple, efficient address system benefits people from all walks of life across the city.

Modern, complex urban life is made possible by the people who dedicated themselves to organizing the invisible infrastructure of the address system.

Does where I live tell anything about me?

The political economy of addresses that assign value to space

An address is not simply a means of specifying a location.

Even adjacent land changes value the moment it is incorporated into different administrative districts.

Research has shown that in the UK, houses or buildings on a 'street' sell for half the price of those on a 'lane', and in the US, houses with an address that includes 'lake' are worth 16 percent more than the median overall house price.

In Victoria, Australia, a study found that property prices on streets with vulgar or humorous names were 20 percent lower than those on other streets.

In New York, where real estate prices in the heart of the city are out of this world, you can even buy and sell an official address.

This is because city authorities sell address change application tickets.

Developers, including Donald Trump, have long recognized that addresses are powerful marketing tools, and have often tried to boost property value by attaching "expensive" addresses, such as those near Central Park, to their buildings.

The situation seems similar in Korea, where economic interests such as real estate and school districts are closely linked to one's address.

Because of the symbolic value of addresses, debates surrounding address revisions occur frequently around the world.

The question of what to commemorate and what not to commemorate is deeply imbued with the political, religious, and historical values of society's members.

This is also the reason why address changes follow revolutions or major events.

In this way, address revision is a microcosm of conflict and a battlefield of memories, but it also serves as a trigger for overcoming mistakes and driving social change.

Like efforts to change addresses built during the Nazi era, or addresses bearing the names of people who supported or defended slavery or apartheid.

Street names are a question of identity and wealth, and they are also a question of race.

Ultimately, it's all about power.

The power to name names, to make history, to decide who is important and who is not, and why.

Some books tell the story of how small objects like pencils and toothpicks changed the world.

This book is not that kind of book.

Rather, it is a complex story about how the enlightenment project of naming and numbering roads became a revolution that transformed human life and society.

- In the text

Over the years, addresses have become a symbol of our identity, a means by which governments exert power, and a way to reflect and improve the structure of society.

Even now, when the significance of living space is highlighted more than ever due to the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic, and even in a future where online spaces will occupy an even greater portion of our lives, the fundamental question of "Where am I?" will remain.

"Address Story" is a book that will serve as an interesting compass for these concerns.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: November 26, 2021

- Format: Paperback book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 496 pages | 428g | 128*188*30mm

- ISBN13: 9788937413919

- ISBN10: 8937413914

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)