Upstream

|

Description

Book Introduction

- A word from MD

-

A new book by Dan Heath, author of "Stick!" and "Switch."The title of this book, "Upstream," means "upstream," and refers to a way of thinking and system that proactively responds to problems.

Depending on whether you fundamentally solve problems upstream or just block them downstream, your organization and life will change.

Behind surprising results that surpass our common sense, there is always an 'upstream' factor.

If you have any problems, go upstream.

July 13, 2021. Economics and Management PD Kang Hyeon-jeong

A new work from the author of the global bestsellers "Stick!" and "Switch."

An immediate Wall Street Journal bestseller

Highly recommended by Charles Duhigg and Daniel Pink

“After reading this book, we adopted the company motto ‘Think Upstream, Go Global & Digital.’”

- Choi Young-moo, CEO of Samsung Fire & Marine Insurance

“The point is not to solve problems, but to prevent them!”

From Expedia, which saved 120 billion won with one question

Even a bike company that reduced its shipping rate by 80% by putting pictures in boxes.

The Secret of Upstream: A Behavioral Strategy That Roots Out Recurring Problems

We go through a cycle of painful problems every day.

Every morning when I leave the house, I panic because I can't find my car keys or wallet, and when I get to work, I'm plagued by endless chores.

In industrial settings, there is constant news of workers dying or being injured, and children and women falling victim to violence.

We dream of a world where efforts and achievements accumulate to improve, but the reality is closer to a third-rate drama where similar problems keep popping up again and again.

Why is this so? Is there a solution?

The title of this book, "Upstream," means "upstream," and refers to a way of thinking and system that proactively responds to problems.

This book argues that, despite the fact that we can fully anticipate and prepare for the root causes of problems, we are so focused on "responding" to problems that we miss countless opportunities.

This very difference, that is, whether a problem is solved at the source upstream or simply blocked downstream, painfully shows how different an organization and a life can be.

From a travel company that saved $100 million with a single question to a hurricane simulation team that saved 60,000 people for just $13 per person, there's always an "upstream" factor behind these incredible, unbelievable results.

Go upstream! This book will be an axe that opens a new path for you, overcoming your instinct to dwell on the small problems of the present and moving forward.

An immediate Wall Street Journal bestseller

Highly recommended by Charles Duhigg and Daniel Pink

“After reading this book, we adopted the company motto ‘Think Upstream, Go Global & Digital.’”

- Choi Young-moo, CEO of Samsung Fire & Marine Insurance

“The point is not to solve problems, but to prevent them!”

From Expedia, which saved 120 billion won with one question

Even a bike company that reduced its shipping rate by 80% by putting pictures in boxes.

The Secret of Upstream: A Behavioral Strategy That Roots Out Recurring Problems

We go through a cycle of painful problems every day.

Every morning when I leave the house, I panic because I can't find my car keys or wallet, and when I get to work, I'm plagued by endless chores.

In industrial settings, there is constant news of workers dying or being injured, and children and women falling victim to violence.

We dream of a world where efforts and achievements accumulate to improve, but the reality is closer to a third-rate drama where similar problems keep popping up again and again.

Why is this so? Is there a solution?

The title of this book, "Upstream," means "upstream," and refers to a way of thinking and system that proactively responds to problems.

This book argues that, despite the fact that we can fully anticipate and prepare for the root causes of problems, we are so focused on "responding" to problems that we miss countless opportunities.

This very difference, that is, whether a problem is solved at the source upstream or simply blocked downstream, painfully shows how different an organization and a life can be.

From a travel company that saved $100 million with a single question to a hurricane simulation team that saved 60,000 people for just $13 per person, there's always an "upstream" factor behind these incredible, unbelievable results.

Go upstream! This book will be an axe that opens a new path for you, overcoming your instinct to dwell on the small problems of the present and moving forward.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

To Korean readers

What is Upstream?

A website that saved $100 million by changing its mindset | What is Upstream? | Why we always lock the barn door after the horse has bolted | Is reporting a crime the best way to solve it? | The American healthcare system and upstream | Let's go upstream!

Part 1: Why We Struggle with the Same Problems Today as Yesterday

Chapter 1.

Because you don't know if the problem in front of you is a problem: problem apathy

Why NFL Players Are Chronically Injured | Chicago Public Schools Raise Kids' Graduation Rates by 25 Percent | Why Did Radiologists Never See the Gorilla? | Fix It or Make It Worse: The Two Faces of Habituation | The Invisible Battle Over Problem Agnosia | Allow Natural Births! | Change Begins When You Accept the Problem

Chapter 2.

The question, "Can I really step forward?": Lack of ownership

If not me, no one can solve it | Make people feel connected to the problem | Why pediatricians advocated for mandatory car seats | The surprising results of ownership | From being a victim of the problem to being the owner of the problem

Chapter 3.

A little later, after I take care of the urgent matters: tunneling syndrome

Why is upstream activity so rare? | Tunneling Syndrome that blinds us | Why smart people form dumb organizations | Laziness is necessary to escape the tunnel | The brain, instinct, and risk aversion | How humans almost became frogs in a pot | How to use our instincts to upstream.

7 Action Strategies to Move Upstream Part 2

Chapter 4.

Recruit the people you need to drive home the seriousness of the problem: Talent

Teens Take Over the Streets | A New Vision for Combating Drugs and Alcohol | Reduce Risks and Increase Protective Factors | Surround the Problem for Upstream Intervention | Women Falling Through the Cracks of the System | The Secrets Gibbs Revealed in Crime Scene Photos | Building a Dream Team to Tackle Domestic Violence | Organizational Success and Data Success | How Rockford Solved Homelessness in One Year | A Mindset-Shifting Victory

Chapter 5.

Redesign the structure that causes the problem: the system

Sweden and Afghanistan in the same city | “But what is water?” | Whether you know it or not, it’s all about the system | A sad tragedy in the social welfare field | Should Donerschoos be abolished? | Don’t solve problems at an individual level | Create power! Start the change! | Even if I’m not the one who reaches the finish line

Chapter 6.

Find the levers you need to solve the problem: Explore the intervention points.

Find the levers you need for success! | A new equation for violence | Becoming a man | Different ways to focus on problems | Is this lever really the right one? | Medical students who left the classroom | Finding the real way to approach problems

Chapter 7.

Create a system to predict risks: Building an alert system

LinkedIn nearly halved its churn rate in two years | The power of early warning: minutes or seconds, saving lives and money | The warning systems that permeate our daily lives | Why thyroid cancer is on the rise in Korea | Sometimes, being wrong is better | Evan and the "Safe to Say Something" program

Chapter 8.

Question the Data: Avoiding Phony Wins

Beware of Illegible Victories | First Illegible Victory: When External Factors Drive Goals | Second Illegible Victory: When Short-Term Measures Succeed but Miss the Original Goal | Third Illegible Victory: When Short-Term Goals Actually Get in the Way of the Ultimate Goal | Use Dual Measurement | Four Questions to Ask Before Upstreaming

Chapter 9.

Beware the Cobra Effect: Avoiding Side Effects

The environmentalists' war on Macquarie Island | The system is more complex than we think | The unexpected side effect: the cobra effect | What kind of scars will the doctor leave behind? | So fast and accurate that it can't possibly improve | How to create a feedback system | A wise leader asks questions before acting | From humility to great success

Chapter 10.

Ultimately, the issue is money: cost.

Who pays for things that never happen? | When money goes into and comes out of the same pocket | When money goes into and comes out of different pockets | Solving the wrong pocket problem | What if someone told you before your appliances broke? | Waving the carrot! Get people moving!

Part 3: Beyond Upstream

Chapter 11.

How to Deal with Unprecedented or Unexpected Problems

Unavoidable, Uncommon, or Unbelievable | Was the Y2K Problem Just a Frantic Frenzy? | If Damage Occurs Despite Predicting the Problem | How New Orleans Averted the Worst | Habits Will Save Us | The Black Ball That Could Destroy Civilization | The Prophet's Dilemma Must Continue

Chapter 12.

Final advice for those moving upstream

Daddy Doll, a doll with a father inside | Leave your problems aside and start from the everyday | If you want to break free from yourself and leap toward a bigger goal | Take on the challenge! Get started! Change your organization!

Next steps

supplement.

Why programs that work for the few don't work for the many

Acknowledgements

annotation

What is Upstream?

A website that saved $100 million by changing its mindset | What is Upstream? | Why we always lock the barn door after the horse has bolted | Is reporting a crime the best way to solve it? | The American healthcare system and upstream | Let's go upstream!

Part 1: Why We Struggle with the Same Problems Today as Yesterday

Chapter 1.

Because you don't know if the problem in front of you is a problem: problem apathy

Why NFL Players Are Chronically Injured | Chicago Public Schools Raise Kids' Graduation Rates by 25 Percent | Why Did Radiologists Never See the Gorilla? | Fix It or Make It Worse: The Two Faces of Habituation | The Invisible Battle Over Problem Agnosia | Allow Natural Births! | Change Begins When You Accept the Problem

Chapter 2.

The question, "Can I really step forward?": Lack of ownership

If not me, no one can solve it | Make people feel connected to the problem | Why pediatricians advocated for mandatory car seats | The surprising results of ownership | From being a victim of the problem to being the owner of the problem

Chapter 3.

A little later, after I take care of the urgent matters: tunneling syndrome

Why is upstream activity so rare? | Tunneling Syndrome that blinds us | Why smart people form dumb organizations | Laziness is necessary to escape the tunnel | The brain, instinct, and risk aversion | How humans almost became frogs in a pot | How to use our instincts to upstream.

7 Action Strategies to Move Upstream Part 2

Chapter 4.

Recruit the people you need to drive home the seriousness of the problem: Talent

Teens Take Over the Streets | A New Vision for Combating Drugs and Alcohol | Reduce Risks and Increase Protective Factors | Surround the Problem for Upstream Intervention | Women Falling Through the Cracks of the System | The Secrets Gibbs Revealed in Crime Scene Photos | Building a Dream Team to Tackle Domestic Violence | Organizational Success and Data Success | How Rockford Solved Homelessness in One Year | A Mindset-Shifting Victory

Chapter 5.

Redesign the structure that causes the problem: the system

Sweden and Afghanistan in the same city | “But what is water?” | Whether you know it or not, it’s all about the system | A sad tragedy in the social welfare field | Should Donerschoos be abolished? | Don’t solve problems at an individual level | Create power! Start the change! | Even if I’m not the one who reaches the finish line

Chapter 6.

Find the levers you need to solve the problem: Explore the intervention points.

Find the levers you need for success! | A new equation for violence | Becoming a man | Different ways to focus on problems | Is this lever really the right one? | Medical students who left the classroom | Finding the real way to approach problems

Chapter 7.

Create a system to predict risks: Building an alert system

LinkedIn nearly halved its churn rate in two years | The power of early warning: minutes or seconds, saving lives and money | The warning systems that permeate our daily lives | Why thyroid cancer is on the rise in Korea | Sometimes, being wrong is better | Evan and the "Safe to Say Something" program

Chapter 8.

Question the Data: Avoiding Phony Wins

Beware of Illegible Victories | First Illegible Victory: When External Factors Drive Goals | Second Illegible Victory: When Short-Term Measures Succeed but Miss the Original Goal | Third Illegible Victory: When Short-Term Goals Actually Get in the Way of the Ultimate Goal | Use Dual Measurement | Four Questions to Ask Before Upstreaming

Chapter 9.

Beware the Cobra Effect: Avoiding Side Effects

The environmentalists' war on Macquarie Island | The system is more complex than we think | The unexpected side effect: the cobra effect | What kind of scars will the doctor leave behind? | So fast and accurate that it can't possibly improve | How to create a feedback system | A wise leader asks questions before acting | From humility to great success

Chapter 10.

Ultimately, the issue is money: cost.

Who pays for things that never happen? | When money goes into and comes out of the same pocket | When money goes into and comes out of different pockets | Solving the wrong pocket problem | What if someone told you before your appliances broke? | Waving the carrot! Get people moving!

Part 3: Beyond Upstream

Chapter 11.

How to Deal with Unprecedented or Unexpected Problems

Unavoidable, Uncommon, or Unbelievable | Was the Y2K Problem Just a Frantic Frenzy? | If Damage Occurs Despite Predicting the Problem | How New Orleans Averted the Worst | Habits Will Save Us | The Black Ball That Could Destroy Civilization | The Prophet's Dilemma Must Continue

Chapter 12.

Final advice for those moving upstream

Daddy Doll, a doll with a father inside | Leave your problems aside and start from the everyday | If you want to break free from yourself and leap toward a bigger goal | Take on the challenge! Get started! Change your organization!

Next steps

supplement.

Why programs that work for the few don't work for the many

Acknowledgements

annotation

Detailed image

Into the book

Most people think it's better to lock the barn door before the horse is stolen.

But our actions are not like that.

Most of what happens in society is optimized for fixing the barn quickly and efficiently.

We celebrate the 'response-recovery-rescue' structure.

But we can do something even greater than that.

The goal is to reduce efforts to turn things around and focus on achieving better results.

--- p.35

'If players play hard, they may get injured.

'You can't change that fact.' I call this mindset 'problem apathy.'

This is the belief that negative outcomes are natural or inevitable.

I think it's something you can't control.

When we are ignorant of a problem, we treat it like the weather.

When the weather is bad, everyone just shrugs.

'What can I do? The weather is like this.'

--- p.41

To succeed with an upstream strategy, you need to identify problems early and identify levers to leverage to change complex systems.

We need to find ways to ensure that we are successfully performing upstream activities, and we also need to consider how we will collaborate with others.

We also need to consider ways to sustain the newly established system.

But remember.

To bring about change, we must first awaken from our insensitivity to the problem.

After not facing the problem or accepting it as inevitable ('Football is a rough game')

So, it is impossible to solve the problem of 'the players will naturally get hurt.'

--- p.49

Not only is the tunneling state self-perpetuating, but it is also emotionally rewarding when we are in it.

There's a certain glory that comes from avoiding a major blunder at the last minute.

It feels great to escape trouble, and heroism is addictive.

You probably have a colleague who seems to enjoy the adventure of staying up all night to meet a really important deadline.

I'm not saying that avoiding trouble is a bad thing.

What this means is that we must be wary of such behavior being repeated.

The need for a hero is usually evidence of a failed system.

--- p.90

How do you escape a tunnel? In times like these, you need to be lazy.

It is deliberately postponing the time or resources to solve a problem rather than investing them immediately.

For example, some hospitals allow staff to meet each morning to review safety-related near misses from the previous day (near-misses where patients were injured or mistakes were made) and to briefly summarize the complexities of the day.

If we had this kind of time, it would be very easy to say that the security tag kept falling off.

These times are not just created to give you some free time.

Rather, it is about getting employees out of the tunnel and thinking about problems at a systemic level.

--- p.91

The system is a machine that determines probabilities.

In the best designed systems (such as those with the highest life expectancy), the odds of success are overwhelmingly high and advantageous.

It's like playing roulette where you win if the ball lands on a red square and you win if it lands on a black square.

But even under a flawed system, the game of roulette still plays out, and even then, elements of choice and chance come into play.

The only way to win in that system is for the ball to land in one of the two green squares marked '0' and '00'.

--- p.139

A well-designed system is the best upstream intervention.

Let's take an example of a car.

In 1967, in the United States, drivers died at an average rate of five deaths for every 160,000 kilometers driven.

Fifty years later, thanks to advances in seatbelts, airbags, braking technology, fewer drunk drivers and improved road conditions, fatalities have fallen to about one per 160,000 kilometers.

This is a result of system improvement, but it was not planned centrally by anyone.

There was no system designer.

It's people like auto safety experts, transportation engineers, and drunk driving prevention volunteers who have transformed the system to keep millions safe.

--- p.141

The first type of phantom victory reflects the old adage, "A rising tide lifts all boats."

If your business is going well, it's tempting to declare it a success, ignoring any hint that it's just the tide.

This happened even during the 1990s when crime was sharply reduced across the United States.

In every city, it seemed as if the police chief had performed a miracle.

Because crime rates have decreased everywhere.

All the various policing philosophies they pursued seemed right.

“Everyone who was a police chief in the 1990s now runs a lucrative consulting firm,” said Jens Ludwig of the Chicago Crime Lab, who appeared in Chapter 6.

“But among the police chiefs who worked in the late 1980s when cocaine was popular, very few ran successful consulting firms.”

--- p.203

In his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, psychologist Daniel Kahneman writes that when faced with a complex problem, our brains often make invisible substitutions, replacing difficult questions with easier ones.

“I once visited the chief investment officer of a large financial firm who had invested tens of millions of dollars in Ford Motor Company stock.

When I asked him how he came to that decision, he said he had recently been to a car show and was deeply impressed.

'Those people know how to make tea!'

--- p.209

If people are rewarded for achieving a certain number and punished for failing, they will cheat.

They will distort statistics, gloss over things, and downgrade events.

They will pursue their goals recklessly, employing every legal means without any qualms (even if it severely violates the spirit of their goals), and will find ways to view even illegal activities with a more favorable eye.

--- p.217

It takes practice to prepare for serious problems.

In theory, it's not a very complicated problem.

But the reason it gets complicated in reality is because this kind of practice goes against the tunneling instinct we talked about earlier.

Agencies continue to address urgent, short-term problems.

It is certainly not urgent to make future plans based on speculation.

As a result, it is difficult to gather people and difficult to obtain funding.

It's not easy to persuade people to cooperate when hardship isn't even imminent.

But our actions are not like that.

Most of what happens in society is optimized for fixing the barn quickly and efficiently.

We celebrate the 'response-recovery-rescue' structure.

But we can do something even greater than that.

The goal is to reduce efforts to turn things around and focus on achieving better results.

--- p.35

'If players play hard, they may get injured.

'You can't change that fact.' I call this mindset 'problem apathy.'

This is the belief that negative outcomes are natural or inevitable.

I think it's something you can't control.

When we are ignorant of a problem, we treat it like the weather.

When the weather is bad, everyone just shrugs.

'What can I do? The weather is like this.'

--- p.41

To succeed with an upstream strategy, you need to identify problems early and identify levers to leverage to change complex systems.

We need to find ways to ensure that we are successfully performing upstream activities, and we also need to consider how we will collaborate with others.

We also need to consider ways to sustain the newly established system.

But remember.

To bring about change, we must first awaken from our insensitivity to the problem.

After not facing the problem or accepting it as inevitable ('Football is a rough game')

So, it is impossible to solve the problem of 'the players will naturally get hurt.'

--- p.49

Not only is the tunneling state self-perpetuating, but it is also emotionally rewarding when we are in it.

There's a certain glory that comes from avoiding a major blunder at the last minute.

It feels great to escape trouble, and heroism is addictive.

You probably have a colleague who seems to enjoy the adventure of staying up all night to meet a really important deadline.

I'm not saying that avoiding trouble is a bad thing.

What this means is that we must be wary of such behavior being repeated.

The need for a hero is usually evidence of a failed system.

--- p.90

How do you escape a tunnel? In times like these, you need to be lazy.

It is deliberately postponing the time or resources to solve a problem rather than investing them immediately.

For example, some hospitals allow staff to meet each morning to review safety-related near misses from the previous day (near-misses where patients were injured or mistakes were made) and to briefly summarize the complexities of the day.

If we had this kind of time, it would be very easy to say that the security tag kept falling off.

These times are not just created to give you some free time.

Rather, it is about getting employees out of the tunnel and thinking about problems at a systemic level.

--- p.91

The system is a machine that determines probabilities.

In the best designed systems (such as those with the highest life expectancy), the odds of success are overwhelmingly high and advantageous.

It's like playing roulette where you win if the ball lands on a red square and you win if it lands on a black square.

But even under a flawed system, the game of roulette still plays out, and even then, elements of choice and chance come into play.

The only way to win in that system is for the ball to land in one of the two green squares marked '0' and '00'.

--- p.139

A well-designed system is the best upstream intervention.

Let's take an example of a car.

In 1967, in the United States, drivers died at an average rate of five deaths for every 160,000 kilometers driven.

Fifty years later, thanks to advances in seatbelts, airbags, braking technology, fewer drunk drivers and improved road conditions, fatalities have fallen to about one per 160,000 kilometers.

This is a result of system improvement, but it was not planned centrally by anyone.

There was no system designer.

It's people like auto safety experts, transportation engineers, and drunk driving prevention volunteers who have transformed the system to keep millions safe.

--- p.141

The first type of phantom victory reflects the old adage, "A rising tide lifts all boats."

If your business is going well, it's tempting to declare it a success, ignoring any hint that it's just the tide.

This happened even during the 1990s when crime was sharply reduced across the United States.

In every city, it seemed as if the police chief had performed a miracle.

Because crime rates have decreased everywhere.

All the various policing philosophies they pursued seemed right.

“Everyone who was a police chief in the 1990s now runs a lucrative consulting firm,” said Jens Ludwig of the Chicago Crime Lab, who appeared in Chapter 6.

“But among the police chiefs who worked in the late 1980s when cocaine was popular, very few ran successful consulting firms.”

--- p.203

In his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, psychologist Daniel Kahneman writes that when faced with a complex problem, our brains often make invisible substitutions, replacing difficult questions with easier ones.

“I once visited the chief investment officer of a large financial firm who had invested tens of millions of dollars in Ford Motor Company stock.

When I asked him how he came to that decision, he said he had recently been to a car show and was deeply impressed.

'Those people know how to make tea!'

--- p.209

If people are rewarded for achieving a certain number and punished for failing, they will cheat.

They will distort statistics, gloss over things, and downgrade events.

They will pursue their goals recklessly, employing every legal means without any qualms (even if it severely violates the spirit of their goals), and will find ways to view even illegal activities with a more favorable eye.

--- p.217

It takes practice to prepare for serious problems.

In theory, it's not a very complicated problem.

But the reason it gets complicated in reality is because this kind of practice goes against the tunneling instinct we talked about earlier.

Agencies continue to address urgent, short-term problems.

It is certainly not urgent to make future plans based on speculation.

As a result, it is difficult to gather people and difficult to obtain funding.

It's not easy to persuade people to cooperate when hardship isn't even imminent.

--- p.286

Publisher's Review

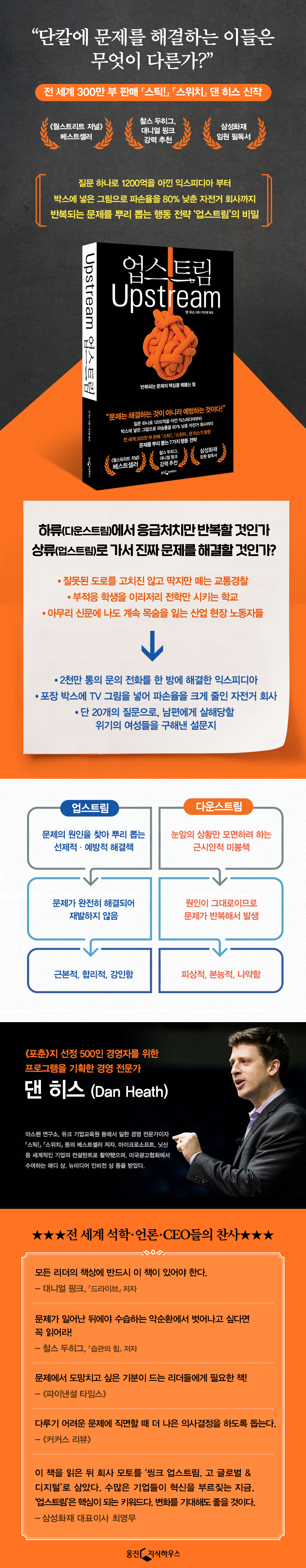

Are you going upstream to really solve the problem?

Are we content to repeat the same thing downstream?

You must overcome the instinct to avoid the situation right in front of you!

How to overcome comfortable weakness and face real problems, Upstream

You went on a picnic to the river with your friends.

A child floats down the river, crying out for help.

When you rescue one, another one comes down, and when you rescue one, another one floats down.

Something must have happened upstream.

Will you head upstream to solve the problem, or will you simply scoop up the endless stream of children floating downstream? "Upstream" is the new book from Dan Heath, the author of "Stick!" and "Switch," beloved by three million readers worldwide.

Dan Heath begins Upstream with the above anecdote.

When most people hear this story, they will say they should go upstream and find out what happened.

But we don't actually do that.

Instead of going upstream, we focus on small solutions that save children.

Because the cause remains, the problem repeats itself, and we tire of only dealing with fake problems.

This is the "downstream" problem that the author says hinders the progress of all organizations and lives.

The author asks us, who are only looking at what is right in front of our noses, painful questions.

Are you wasting time addressing recurring small issues? Are you postponing urgent matters with the excuse that you have more pressing concerns? Are you trapped in a tunnel of vision and thinking due to money, time, or circumstances? Are you mistakenly believing your problems aren't your own? This book argues that if we move beyond these short-sighted, stopgap measures prevalent in society and individuals and adopt a more fundamental, "upstream" approach, drastically different outcomes are possible.

There are many examples of companies that fell into organizational traps but overcame them, such as a bicycle company that reduced its product delivery rate by 80% by printing expensive TV pictures on its boxes (page 142), LinkedIn that reduced its churn rate by 50% by predicting which customers would cancel their service (page 180), and a high school that increased its graduation rate by over 20% by focusing its resources on first-year (9th grade) students (page 42).

In doing so, it presents three reasons why we continue to struggle with the same problems (problem apathy, lack of ownership, tunneling syndrome) and seven upstream strategies (exploring talent, systems, and intervention points, etc.) for truly solving the problem.

It makes you realize your own weakness in avoiding the real problem while solving only small problems, and provides realistic upstream solutions.

As in his previous works, "Stick!" and "Switch," the author accurately points out the most fundamental points for personal and social change.

Why do employees only act passively?

Why do smart people become stupid when they get together?

Finding the real problem with data

Focus your organization's resources on the target!

"Upstream" is also helpful for leaders of companies and organizations.

When we look at each individual employee, they are talented individuals with strengths and abilities, but when they work together, they often lose their long-term perspective and vision and become short-sighted.

The biggest problem is when we focus solely on achieving the goals set for organizational innovation, thereby distorting the original intended innovation itself.

What can we do about police who focus on "playing cop"—catching traffic violations—rather than working hard to prevent traffic accidents? How can we stop police officers who downplay rape as "service theft" to achieve crime reduction goals?

What about school principals who are desperate to transfer underachieving students to boost graduation rates? How can we change an organizational culture where setting specific goals only achieves numbers, contrary to the original intent? This book provides vivid examples of how upstream behavior can be used to transform organizational culture and translate that into results.

To avoid falling into the trap of "company play"—setting lofty goals, only increasing the achievement rate, and praising yourself—you can gain several weapons to focus on.

Of the weapons the author has handed me, one that is particularly interesting is the 'double measurement method'.

"Upstream" tells us that simple data obscures the problem, so we need to use a dual measurement method that considers both quality and quantity.

For example, in Boston, a curious phenomenon was discovered where sidewalk repairs were concentrated in wealthy neighborhoods with good sidewalks, rather than poor neighborhoods with severe sidewalk damage.

The poor did not file complaints because they thought the government would not help them, and the politicians only listened to the rich.

This phenomenon cannot be detected by relying solely on faulty data such as the number of complaints handled.

But most leaders use data only as a whip for rewards and punishments, enslaving their employees and ultimately exacerbating the problem.

In addition, "Upstream" offers solutions to numerous challenges faced by leaders and organizations seeking to solve problems, including how to accurately assess organizational performance, how to prevent adverse effects from incorrect measures, and how to identify appropriate intervention points for problem resolution.

From the small, daily chores

Public areas for all of us, including healthcare, welfare, and education.

There is a different way to deal with the fundamental problem.

"Upstream" provides a "frame" for examining and identifying problems in numerous social phenomena, including not only individual lives but also corporate operations and public issues.

For example, the author frequently cites the American health care system as an example of a problem in the public sector.

The US has a distorted system (downstream) where it spends astronomical amounts of money to cure diseases after they occur, while it neglects effective methods (upstream) that cost a small amount of money to prevent major diseases.

On the other hand, Korea has suffered side effects such as a 15-fold increase in the incidence of thyroid cancer (which is not particularly fatal) due to excessive health checkups.

Perhaps the best example of an upstream solution is Kelly Dunn and Jacqueline Campbell's '20-Item Questionnaire'.

They noticed several patterns in the way women were abused by their husbands and ended up murdered, and created a questionnaire to prevent these disasters.

Another good example would be a smart elevator that checks if the elevator door closes slowly and sends a repairman before a breakdown occurs.

The "upstream" frame is a universal problem-solving framework that helps us honestly look at the true source of a problem and pinpoint the precise point of intervention.

We often ignore the bigger problems by looking for small solutions, but because we all make such weak choices, lives are ruined and buildings collapse.

Are your decisions now truly directed upstream? When you're tempted to close the door to shallow satisfaction, this is the mindset you need to recall once again. It's a mindset you must master for your own life and our society: "upstream."

Are we content to repeat the same thing downstream?

You must overcome the instinct to avoid the situation right in front of you!

How to overcome comfortable weakness and face real problems, Upstream

You went on a picnic to the river with your friends.

A child floats down the river, crying out for help.

When you rescue one, another one comes down, and when you rescue one, another one floats down.

Something must have happened upstream.

Will you head upstream to solve the problem, or will you simply scoop up the endless stream of children floating downstream? "Upstream" is the new book from Dan Heath, the author of "Stick!" and "Switch," beloved by three million readers worldwide.

Dan Heath begins Upstream with the above anecdote.

When most people hear this story, they will say they should go upstream and find out what happened.

But we don't actually do that.

Instead of going upstream, we focus on small solutions that save children.

Because the cause remains, the problem repeats itself, and we tire of only dealing with fake problems.

This is the "downstream" problem that the author says hinders the progress of all organizations and lives.

The author asks us, who are only looking at what is right in front of our noses, painful questions.

Are you wasting time addressing recurring small issues? Are you postponing urgent matters with the excuse that you have more pressing concerns? Are you trapped in a tunnel of vision and thinking due to money, time, or circumstances? Are you mistakenly believing your problems aren't your own? This book argues that if we move beyond these short-sighted, stopgap measures prevalent in society and individuals and adopt a more fundamental, "upstream" approach, drastically different outcomes are possible.

There are many examples of companies that fell into organizational traps but overcame them, such as a bicycle company that reduced its product delivery rate by 80% by printing expensive TV pictures on its boxes (page 142), LinkedIn that reduced its churn rate by 50% by predicting which customers would cancel their service (page 180), and a high school that increased its graduation rate by over 20% by focusing its resources on first-year (9th grade) students (page 42).

In doing so, it presents three reasons why we continue to struggle with the same problems (problem apathy, lack of ownership, tunneling syndrome) and seven upstream strategies (exploring talent, systems, and intervention points, etc.) for truly solving the problem.

It makes you realize your own weakness in avoiding the real problem while solving only small problems, and provides realistic upstream solutions.

As in his previous works, "Stick!" and "Switch," the author accurately points out the most fundamental points for personal and social change.

Why do employees only act passively?

Why do smart people become stupid when they get together?

Finding the real problem with data

Focus your organization's resources on the target!

"Upstream" is also helpful for leaders of companies and organizations.

When we look at each individual employee, they are talented individuals with strengths and abilities, but when they work together, they often lose their long-term perspective and vision and become short-sighted.

The biggest problem is when we focus solely on achieving the goals set for organizational innovation, thereby distorting the original intended innovation itself.

What can we do about police who focus on "playing cop"—catching traffic violations—rather than working hard to prevent traffic accidents? How can we stop police officers who downplay rape as "service theft" to achieve crime reduction goals?

What about school principals who are desperate to transfer underachieving students to boost graduation rates? How can we change an organizational culture where setting specific goals only achieves numbers, contrary to the original intent? This book provides vivid examples of how upstream behavior can be used to transform organizational culture and translate that into results.

To avoid falling into the trap of "company play"—setting lofty goals, only increasing the achievement rate, and praising yourself—you can gain several weapons to focus on.

Of the weapons the author has handed me, one that is particularly interesting is the 'double measurement method'.

"Upstream" tells us that simple data obscures the problem, so we need to use a dual measurement method that considers both quality and quantity.

For example, in Boston, a curious phenomenon was discovered where sidewalk repairs were concentrated in wealthy neighborhoods with good sidewalks, rather than poor neighborhoods with severe sidewalk damage.

The poor did not file complaints because they thought the government would not help them, and the politicians only listened to the rich.

This phenomenon cannot be detected by relying solely on faulty data such as the number of complaints handled.

But most leaders use data only as a whip for rewards and punishments, enslaving their employees and ultimately exacerbating the problem.

In addition, "Upstream" offers solutions to numerous challenges faced by leaders and organizations seeking to solve problems, including how to accurately assess organizational performance, how to prevent adverse effects from incorrect measures, and how to identify appropriate intervention points for problem resolution.

From the small, daily chores

Public areas for all of us, including healthcare, welfare, and education.

There is a different way to deal with the fundamental problem.

"Upstream" provides a "frame" for examining and identifying problems in numerous social phenomena, including not only individual lives but also corporate operations and public issues.

For example, the author frequently cites the American health care system as an example of a problem in the public sector.

The US has a distorted system (downstream) where it spends astronomical amounts of money to cure diseases after they occur, while it neglects effective methods (upstream) that cost a small amount of money to prevent major diseases.

On the other hand, Korea has suffered side effects such as a 15-fold increase in the incidence of thyroid cancer (which is not particularly fatal) due to excessive health checkups.

Perhaps the best example of an upstream solution is Kelly Dunn and Jacqueline Campbell's '20-Item Questionnaire'.

They noticed several patterns in the way women were abused by their husbands and ended up murdered, and created a questionnaire to prevent these disasters.

Another good example would be a smart elevator that checks if the elevator door closes slowly and sends a repairman before a breakdown occurs.

The "upstream" frame is a universal problem-solving framework that helps us honestly look at the true source of a problem and pinpoint the precise point of intervention.

We often ignore the bigger problems by looking for small solutions, but because we all make such weak choices, lives are ruined and buildings collapse.

Are your decisions now truly directed upstream? When you're tempted to close the door to shallow satisfaction, this is the mindset you need to recall once again. It's a mindset you must master for your own life and our society: "upstream."

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: June 25, 2021

- Page count, weight, size: 364 pages | 656g | 152*225*23mm

- ISBN13: 9788901251684

- ISBN10: 890125168X

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)