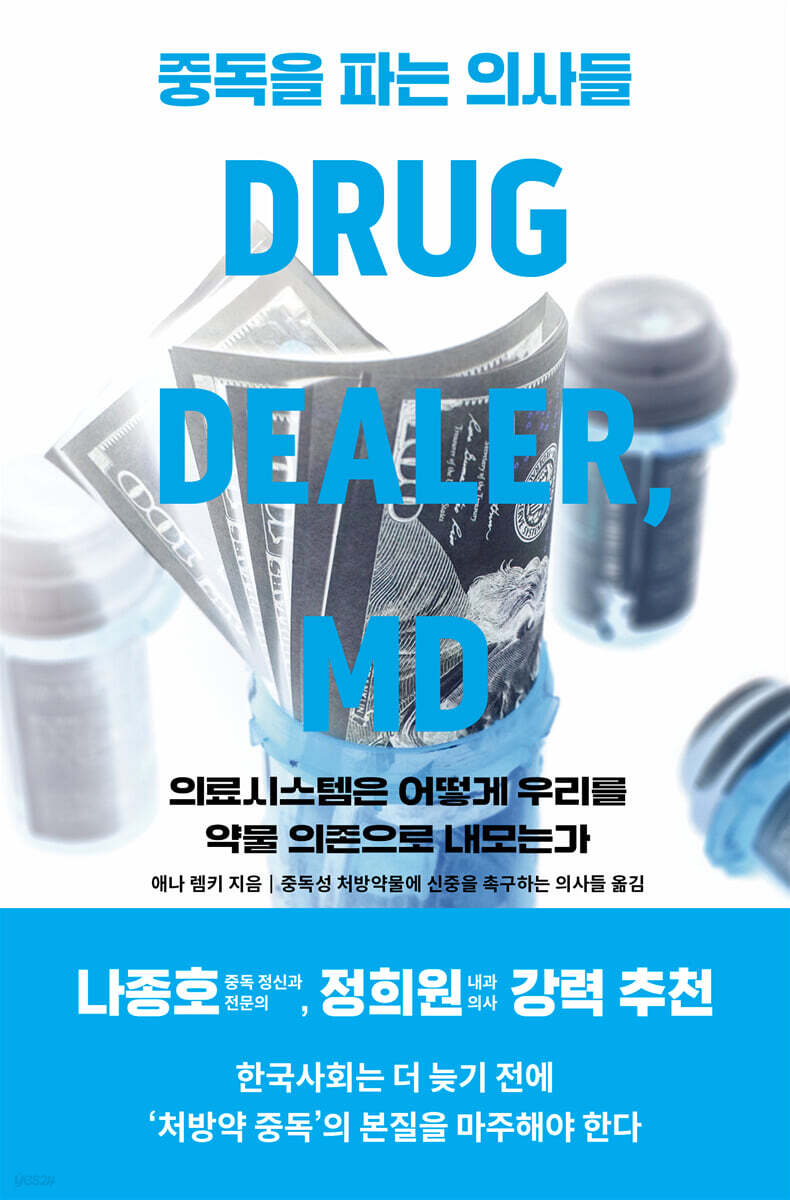

Doctors who sell addiction

|

Description

Book Introduction

In an era where drugs are consumed like espresso,

The war against addiction is ongoing.

Deceiving doctors and poisoning patients

The true face of the medical system that engulfs us in a vast web

※ Highly recommended by Na Jong-ho (addiction psychiatrist) and Jeong Hee-won (internist) ※

Pain relievers, mood stabilizers, sleeping pills, antidepressants, concentration enhancers… Modern people’s lives are surrounded by various drugs.

From pain relievers prescribed for colds, various inflammations, and muscle pain to various psychiatric medications that alleviate difficult-to-manage mental pain or problems, various medications that act quickly on pain and symptoms greatly improve our quality of life.

The remarkable advancements in medicine and the pharmaceutical industry have ushered in an era where drugs can be consumed as easily and lightly as ordering an espresso.

But what if these "legally and safely" prescribed drugs by doctors actually trap us in the trap of serious addiction? What if "prescription drugs," rather than narcotics or alcohol, lead us to drug dependence and addiction? What if, instead of achieving "treatment," we inflict yet another "disease" and "damage"? In the United States, approximately 16,000 people die from opioid overdoses each year, and South Korea, with its increasing use of "medical narcotics," is also not immune to the risk of death.

The reality of Korean society is that approximately 20.01 million people (4 out of 10 people) have been prescribed medical narcotics at least once (2024 Ministry of Food and Drug Safety statistics).

Anna Lemke, the author of "Dopamine Nation," who received much love from Korean readers, diagnoses the problem of "prescription drug addiction" in "The Addiction Doctors" and continues her sharp insight into its root cause.

How does the distorted medical system work, leading doctors to overprescribe and thus addict patients? Why do we so overestimate the effectiveness of medications and ignore their harmful effects? In this book, the author interviews practicing doctors and his own patients to delve deeply into the background and mechanisms behind this reality.

As those who recommended this book say, "Doctors Who Sell Addiction" is a "desperate warning and earnest request to Korean society and Korean doctors" (Na Jong-ho) beyond the American medical field, and is a masterpiece that "goes beyond pointing out the reality of 'drug addiction' and raises important topics of self-care and self-directed living" (Jeong Hee-won).

The war against addiction is ongoing.

Deceiving doctors and poisoning patients

The true face of the medical system that engulfs us in a vast web

※ Highly recommended by Na Jong-ho (addiction psychiatrist) and Jeong Hee-won (internist) ※

Pain relievers, mood stabilizers, sleeping pills, antidepressants, concentration enhancers… Modern people’s lives are surrounded by various drugs.

From pain relievers prescribed for colds, various inflammations, and muscle pain to various psychiatric medications that alleviate difficult-to-manage mental pain or problems, various medications that act quickly on pain and symptoms greatly improve our quality of life.

The remarkable advancements in medicine and the pharmaceutical industry have ushered in an era where drugs can be consumed as easily and lightly as ordering an espresso.

But what if these "legally and safely" prescribed drugs by doctors actually trap us in the trap of serious addiction? What if "prescription drugs," rather than narcotics or alcohol, lead us to drug dependence and addiction? What if, instead of achieving "treatment," we inflict yet another "disease" and "damage"? In the United States, approximately 16,000 people die from opioid overdoses each year, and South Korea, with its increasing use of "medical narcotics," is also not immune to the risk of death.

The reality of Korean society is that approximately 20.01 million people (4 out of 10 people) have been prescribed medical narcotics at least once (2024 Ministry of Food and Drug Safety statistics).

Anna Lemke, the author of "Dopamine Nation," who received much love from Korean readers, diagnoses the problem of "prescription drug addiction" in "The Addiction Doctors" and continues her sharp insight into its root cause.

How does the distorted medical system work, leading doctors to overprescribe and thus addict patients? Why do we so overestimate the effectiveness of medications and ignore their harmful effects? In this book, the author interviews practicing doctors and his own patients to delve deeply into the background and mechanisms behind this reality.

As those who recommended this book say, "Doctors Who Sell Addiction" is a "desperate warning and earnest request to Korean society and Korean doctors" (Na Jong-ho) beyond the American medical field, and is a masterpiece that "goes beyond pointing out the reality of 'drug addiction' and raises important topics of self-care and self-directed living" (Jeong Hee-won).

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommended Article | Jong-ho Na, Hee-won Jeong, 7

To our Korean readersㆍ14

Preface to the Korean Edition | Anna Lemke, Chang-Hyun Jang, 16

Drug and Pharmaceutical Terminology: 24

Prologue: In the Great Net 39

The Addictive Prescription Drug Pandemic | Controlled Substances and Addiction | A Tangled Web

Chapter 1: What Is Addiction?: Risk Factors and Keys to Recovery 53

What is Addiction? | Risk Factors That Trigger Addiction | Finding the Path to Recovery

Chapter 2: The Prescription Drug Trap: A New Gateway to Addiction 73

Vicodin, the Gateway Drug | The Overprescription Epidemic Sweeping America | Online Illegal Pharmacies | From Vicodin to Heroin | Addiction Treatment | Finding the True 'Dragon' | The Gateway to Addiction Becomes a Runway

Chapter 3: How Pain and Psychological Diversity Become Disease: A Culture That Rejects Alternative Narratives 103

Is Pain a Curse? | When Pain Comes to Become a Mental Scar | The Unbearable Weight of Pain | How Psychological Diversity Becomes Mental Illness | The Drug That Fuels Addiction | Relearning How to Live

Chapter 4: The Big Drug Cartels: Collusion Between Pharmaceutical Companies and the Medical Community 131

The Opioid Painkiller Pandemic | Academic Physicians' Responsibilities | Professional Medical Societies' Responsibilities | The Joint Commission on Medical Institutions' Responsibilities | The FDA's Responsibilities | The Birth of a Runaway Train

Chapter 5: Patients Seeking Drugs: Beyond Blame or Neglect: What to Do 161

Getting the Drug | Beyond the Concept of 'Making Illness' | The Biochemical Mechanisms of Addiction | A Revolution in Addiction Treatment | Denial: A Defense Mechanism That Blocks Reality | Tips for Addiction Treatment

Chapter 6: The Paradox of Being a Professional Patient: Being Pushed to Remain a Patient 187

Is staying sick a necessity for survival? | The growing number of disability beneficiaries | The medicalization of poverty | The inequalities surrounding addiction | Illness identity | Is disability policy a safety net or a social detriment?

Chapter 7: Addiction-Creating Treatments?: Discussing Doctors' Responsibilities 209

What is a Doctor? | When a Compassionate Doctor Meets a Drug Patient | Narcissistic Rage, Retaliation, and the Consequences | Opioid Refugees | Doctors Who Turn Away Patients

Chapter 8: When Patients Become Commodities: The Health Care System That Fuels Drug Abuse 229

Corrupt doctors and drug abuse clinics | Medical industrialization | The trap of 'patient satisfaction' | Mismatched treatment that falls short of Toyota | Drugs like espresso

Chapter 9: Addiction, the Neglected Disease: Systems and Stigma That Block Treatment 255

A History of Perceptions Surrounding Addiction | The Multiple Pathways to Addiction | Substitute Rewards That Curb Drug Use | Heroin Addiction | The Revolving Door Phenomenon | Benzodiazepines: The Hidden Addictive Drug | Beyond the "Drug-Critical Patient"

Chapter 10: Stopping the Vicious Cycle: Toward a Relationship- and Community-Centered Healthcare Infrastructure 285

The Invisible Force | How to End the Vicious Cycle | New Treatment Models | A Call for Change

Acknowledgmentsㆍ301

Referencesㆍ302

Translator's Note | Avoiding the Maze of Drugsㆍ315

Searchㆍ321

Translator's Introductionㆍ329

To our Korean readersㆍ14

Preface to the Korean Edition | Anna Lemke, Chang-Hyun Jang, 16

Drug and Pharmaceutical Terminology: 24

Prologue: In the Great Net 39

The Addictive Prescription Drug Pandemic | Controlled Substances and Addiction | A Tangled Web

Chapter 1: What Is Addiction?: Risk Factors and Keys to Recovery 53

What is Addiction? | Risk Factors That Trigger Addiction | Finding the Path to Recovery

Chapter 2: The Prescription Drug Trap: A New Gateway to Addiction 73

Vicodin, the Gateway Drug | The Overprescription Epidemic Sweeping America | Online Illegal Pharmacies | From Vicodin to Heroin | Addiction Treatment | Finding the True 'Dragon' | The Gateway to Addiction Becomes a Runway

Chapter 3: How Pain and Psychological Diversity Become Disease: A Culture That Rejects Alternative Narratives 103

Is Pain a Curse? | When Pain Comes to Become a Mental Scar | The Unbearable Weight of Pain | How Psychological Diversity Becomes Mental Illness | The Drug That Fuels Addiction | Relearning How to Live

Chapter 4: The Big Drug Cartels: Collusion Between Pharmaceutical Companies and the Medical Community 131

The Opioid Painkiller Pandemic | Academic Physicians' Responsibilities | Professional Medical Societies' Responsibilities | The Joint Commission on Medical Institutions' Responsibilities | The FDA's Responsibilities | The Birth of a Runaway Train

Chapter 5: Patients Seeking Drugs: Beyond Blame or Neglect: What to Do 161

Getting the Drug | Beyond the Concept of 'Making Illness' | The Biochemical Mechanisms of Addiction | A Revolution in Addiction Treatment | Denial: A Defense Mechanism That Blocks Reality | Tips for Addiction Treatment

Chapter 6: The Paradox of Being a Professional Patient: Being Pushed to Remain a Patient 187

Is staying sick a necessity for survival? | The growing number of disability beneficiaries | The medicalization of poverty | The inequalities surrounding addiction | Illness identity | Is disability policy a safety net or a social detriment?

Chapter 7: Addiction-Creating Treatments?: Discussing Doctors' Responsibilities 209

What is a Doctor? | When a Compassionate Doctor Meets a Drug Patient | Narcissistic Rage, Retaliation, and the Consequences | Opioid Refugees | Doctors Who Turn Away Patients

Chapter 8: When Patients Become Commodities: The Health Care System That Fuels Drug Abuse 229

Corrupt doctors and drug abuse clinics | Medical industrialization | The trap of 'patient satisfaction' | Mismatched treatment that falls short of Toyota | Drugs like espresso

Chapter 9: Addiction, the Neglected Disease: Systems and Stigma That Block Treatment 255

A History of Perceptions Surrounding Addiction | The Multiple Pathways to Addiction | Substitute Rewards That Curb Drug Use | Heroin Addiction | The Revolving Door Phenomenon | Benzodiazepines: The Hidden Addictive Drug | Beyond the "Drug-Critical Patient"

Chapter 10: Stopping the Vicious Cycle: Toward a Relationship- and Community-Centered Healthcare Infrastructure 285

The Invisible Force | How to End the Vicious Cycle | New Treatment Models | A Call for Change

Acknowledgmentsㆍ301

Referencesㆍ302

Translator's Note | Avoiding the Maze of Drugsㆍ315

Searchㆍ321

Translator's Introductionㆍ329

Into the book

We have now reached a turning point of no return.

Too many patients are being prescribed medications for completely unfounded reasons, and sometimes for reasons that have nothing to do with helping the patient.

We prescribe drugs because we overestimate their effectiveness and underestimate their harm.

We prescribe because the medical system, driven by the pursuit of profit, encourages us to do so.

And I prescribe it because I don't have enough time or knowledge to explore other methods.

I hope that "Doctors Who Sell Addiction" will clearly show why even well-intentioned doctors prescribe medications in ways that harm their patients, and also suggest a direction for us to take going forward.

--- p.15

A multidisciplinary approach encompassing psychiatry, psychology, addiction medicine, social work, and community services is not yet fully developed in either the United States or Korea.

This treatment model is particularly rare in Korea.

Treatment is disjointed, communication between therapists is limited, and referrals to addiction treatment or behavioral treatment programs are inconsistent.

Community-based aftercare is also inadequate.

--- p.18

I realized that my fellow doctors and I were trapped in a 'crazy' system.

The reality is that we cannot help but prescribe more opioid painkillers to patients with obvious addiction, even though we know full well that opioid painkillers are harmful to patients.

I advised my fellow physicians to gradually taper off opioid painkillers and refer patients to addiction treatment centers.

But none of my recommendations were accepted.

--- p.43

This book attempts to understand how well-meaning American doctors, who practiced medicine to save lives and alleviate suffering, ended up prescribing drugs that were ultimately fatal, and how patients seeking treatment for illness and injury became addicted to the drugs they believed would save them.

--- p.49~50

Big Medicine was the driving force behind the opioid paradigm shift, and Big Pharma was the covert and powerful force behind it.

Big Medicine provided the legitimacy, and Big Pharma provided the funding needed to get the message across.

No one could have predicted that this collaboration would succeed and create the runaway locomotive that is the opioid epidemic.

Too many patients are being prescribed medications for completely unfounded reasons, and sometimes for reasons that have nothing to do with helping the patient.

We prescribe drugs because we overestimate their effectiveness and underestimate their harm.

We prescribe because the medical system, driven by the pursuit of profit, encourages us to do so.

And I prescribe it because I don't have enough time or knowledge to explore other methods.

I hope that "Doctors Who Sell Addiction" will clearly show why even well-intentioned doctors prescribe medications in ways that harm their patients, and also suggest a direction for us to take going forward.

--- p.15

A multidisciplinary approach encompassing psychiatry, psychology, addiction medicine, social work, and community services is not yet fully developed in either the United States or Korea.

This treatment model is particularly rare in Korea.

Treatment is disjointed, communication between therapists is limited, and referrals to addiction treatment or behavioral treatment programs are inconsistent.

Community-based aftercare is also inadequate.

--- p.18

I realized that my fellow doctors and I were trapped in a 'crazy' system.

The reality is that we cannot help but prescribe more opioid painkillers to patients with obvious addiction, even though we know full well that opioid painkillers are harmful to patients.

I advised my fellow physicians to gradually taper off opioid painkillers and refer patients to addiction treatment centers.

But none of my recommendations were accepted.

--- p.43

This book attempts to understand how well-meaning American doctors, who practiced medicine to save lives and alleviate suffering, ended up prescribing drugs that were ultimately fatal, and how patients seeking treatment for illness and injury became addicted to the drugs they believed would save them.

--- p.49~50

Big Medicine was the driving force behind the opioid paradigm shift, and Big Pharma was the covert and powerful force behind it.

Big Medicine provided the legitimacy, and Big Pharma provided the funding needed to get the message across.

No one could have predicted that this collaboration would succeed and create the runaway locomotive that is the opioid epidemic.

--- p.159~160

Publisher's Review

In an era where drugs are consumed like espresso,

The war against addiction is ongoing.

Deceiving doctors and poisoning patients

The true face of the medical system that engulfs us in a vast web

※ Highly recommended by Na Jong-ho (addiction psychiatrist) and Jeong Hee-won (internist) ※

Pain relievers, mood stabilizers, sleeping pills, antidepressants, concentration enhancers… Modern people’s lives are surrounded by various drugs.

From pain relievers prescribed for colds, various inflammations, and muscle pain to various psychiatric medications that alleviate difficult-to-manage mental pain or problems, various medications that act quickly on pain and symptoms greatly improve our quality of life.

The remarkable advancements in medicine and the pharmaceutical industry have ushered in an era where drugs can be consumed as easily and lightly as ordering an espresso.

But what if these "legally and safely" prescribed drugs by doctors actually trap us in the trap of serious addiction? What if "prescription drugs," rather than narcotics or alcohol, lead us to drug dependence and addiction? What if, instead of achieving "treatment," we inflict yet another "disease" and "damage"? In the United States, approximately 16,000 people die from opioid overdoses each year, and South Korea, with its increasing use of "medical narcotics," is also not immune to the risk of death.

The reality of Korean society is that approximately 20.01 million people (4 out of 10 people) have been prescribed medical narcotics at least once (2024 Ministry of Food and Drug Safety statistics).

Anna Lemke, the author of "Dopamine Nation," who received much love from Korean readers, diagnoses the problem of "prescription drug addiction" in "The Addiction Doctors" and continues her sharp insight into its root cause.

How does the distorted medical system work, leading doctors to overprescribe and thus addict patients? Why do we so overestimate the effectiveness of medications and ignore their harmful effects? In this book, the author interviews practicing doctors and his own patients to delve deeply into the background and mechanisms behind this reality.

As those who recommended this book say, "Doctors Who Sell Addiction" is a "desperate warning and earnest request to Korean society and Korean doctors" (Na Jong-ho) beyond the American medical field, and is a masterpiece that "goes beyond pointing out the reality of 'drug addiction' and raises important topics of self-care and self-directed living" (Jeong Hee-won).

The War on Drugs: The Drugs That Fuel Addiction

“We now live in an age where going to the emergency room and getting a shot of Dilaudid (a powerful opioid painkiller containing hydromorphone) or a prescription or two of Klonopin (a benzodiazepine containing clonazepam) is as easy as ordering an espresso.

“It is not the individuals who seek drugs for non-medical purposes who are responsible for these situations, but the system that allows them to happen.” (p. 254)

The author, an addiction psychiatrist with tens of thousands of clinical experiences, analyzes that the background to today's accelerating 'addictive prescription drug epidemic' is that the standard for 'unbearable pain' was lowered to an unprecedented level as the perspective on pain changed in the latter half of the 20th century, and as a result, the prescription and consumption of addictive prescription drugs by patients complaining of physical and mental pain increased.

As the term "prescription drugs" suggests, most patients do not obtain their medications illegally through drug dealers.

They were legally prescribed medication by their doctors, and that's exactly what led them into the trap of addiction.

The lives of such people follow a typical downward curve, being ruined by drugs.

Not only do they lose their jobs, friends, and family, but many end up on the verge of death from opioid overdoses.

The authors also present the case of a patient who was prescribed 1,200 opioid pills by 16 different doctors over several months before being admitted to the hospital.

The author strongly emphasizes that this case is by no means exceptional.

In fact, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) declared a “prescription drug epidemic” on November 1, 2011, and clearly stated that the cause of this epidemic was “opioid painkillers and some psychiatric medications that are being prescribed more widely by doctors.”

“In 2010, for the first time in history, unintentional drug poisonings became the leading cause of death in the United States, surpassing deaths from traffic accidents.

The disaster was widespread and racially insensitive, with the largest increases occurring among white, middle-class people living in rural areas.”

In particular, the younger generation, represented by the millennial generation (born between 1980 and 2000), actively accepted the 'promise of hope' that a better life could be achieved through chemical substances called drugs.

Many young people and teenagers today take addiction to prescription drugs lightly.

In the morning, you take Adderall, a stimulant, to get a feel for yourself; at lunch, you take Vicodin, an opioid painkiller, to treat a workout injury; in the evening, you use "medical" marijuana to relax your mind; and at night, you take Xanax, a benzodiazepine, to help you sleep.

Central nervous system stimulants (psycho-stimulants) taken to improve concentration are often considered nothing more than 'good study aids'.

This reality is not limited to the American reality that the author primarily deals with.

South Korea, which has long been called a "drug-free country," is not much different from the United States.

As author Anna Lemke and translator Chang-Hyeon Jang (Doctors Urge Caution with Addictive Prescription Drugs) unanimously state, “The reality of addictive prescription drug abuse in American society is a warning for Korea’s future.”

This is because many of the factors that promote overprescription in the United States are also at work in Korea.

Although there may be differences depending on the treatment environment, the time for psychiatric outpatient treatment in Korea is relatively short (less than 10 minutes).

Also, as in the US, the more patients seen in a short period of time, the greater the financial compensation (of the doctor).

Korea also tends to be lenient in prescribing drugs that can cause addiction.

In particular, the barriers to prescribing drugs with clear risks of dependence and abuse, such as benzodiazepine anti-anxiety drugs, the sleep aid zolpidem, and the psychostimulant methylphenidate, are low.

Third, Korea still has a weak level of 'shared decision-making.'

Patients and their families are rarely provided with adequate information about the risks, benefits, and alternatives of medications.

How Pain and Psychological Diversity Become Disease: A Culture That Rejects Alternative Narratives

The tendency for both doctors and patients to rely excessively on medication is fundamentally linked to a contemporary culture that rejects alternative disease narratives.

Our contemporary culture stifles diverse lifestyles by labeling pain a “curse to be completely avoided” and various emotional, cognitive, and temperamental differences as “diseases.”

Pain was originally a desirable element of the healing process, but with the advancement of pain treatment in the mid-1850s, it began to be viewed as something to be eliminated, and the result is today's reality where the standard for "unbearable pain" has been lowered to an unprecedented level.

The modern disease narrative, which defines human differences and diversity as illness, also emphasizes only treatments that eliminate such differences.

“If we define human diversity as a disease, we naturally come to the conclusion that we need treatment to eliminate these differences.

This idea is supported by the contemporary view of mental illness, which sees thoughts, feelings, and behaviors as nothing more than the activation of neurons in a chemical soup.

“Modifying brain chemistry has become a new way to normalize differences.”

The author points out the "reverse logic" of his patient Karen, who, after following her friends into taking Adderall to improve her academic focus and experiencing its effects, came to believe (through its effects) that she had ADHD.

This way of thinking, prevalent in the psychiatric community, is that if you take a certain medication and your condition improves, you must be suffering from the disease that the medication is treating.

However, in reality, almost anyone can improve their concentration and performance by taking psychostimulants, even if they do not have ADHD.

We are all born different, mentally and physically.

However, today's society and culture too easily label those differences as diseases and try to treat them with medication.

Karen's case, where she attributed her learning difficulties to a pathological brain problem and began taking psychostimulants for long-term treatment for attention deficit disorder, vividly illustrates this tendency prevalent in our culture.

“Today, mental illness encompasses not only deviant behavior but also subtle differences between individuals.

It is explained as a mental illness not only to be unable to adapt to something, but also to not be able to show outstanding abilities.

“Therefore, now even students with below-average learning abilities or unique recluse individuals are at risk of being diagnosed with a mental illness.” (p. 118)

Of course, for some people, being diagnosed with a mental illness can help clear their doubts.

This can provide access to resources that might otherwise be unavailable and a framework for understanding one's differences, potentially freeing one from stigma and shame.

What is really problematic is the hasty approach of going beyond simply diagnosing the differences and trying to 'cure' them with a 'magic pill'.

You must be especially careful when the drug carries a risk of addiction.

“Doctors, especially psychiatrists, are largely responsible for the prevalence of this approach.

“Over the past 30 years, psychiatrists have increasingly relied on psychoactive drugs to treat patients’ emotional distress, psychiatric symptoms, or life crises, leaving psychotherapy to others.” (p. 119)

Big Drug Cartels and Medical Mills: The Healthcare System That Fuels Drug Abuse

So why do psychiatrists so readily abandon psychoanalysis and other talk therapies in favor of "magic pills"? Why do even doctors allow patients to become dependent on prescription medications, or why do they often overlook the risks of medications? We might rephrase this question this way.

What makes well-intentioned efforts and sincerity to improve the lives of those suffering from pain ineffective? Behind this reality lies a corrupt medical system, and "Doctors Who Sell Addiction" closely examines this system.

"This book painfully demonstrates how devastating the consequences can be when doctors' desire to alleviate patients' pain combines with their ignorance about addiction in a corrupt system." (Na Jong-ho)

In the case of the United States, which has already suffered from the pain of the 'addictive prescription drug epidemic', efforts are being made to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past, such as introducing Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs) and allowing doctors to check online which controlled substances (benzodiazepines, ADHD medications, opioid drugs, etc.) patients have been prescribed.

However, it can be said that American society, as well as Korean society, is still fighting a 'war on drugs', because it is not easy to bring about change within a structurally sick system.

Moreover, the existence of patients who suffer from various complications due to drug addiction, suffer irreversible damage, and even die further highlights the seriousness of this problem.

What distorts and corrupts the healthcare system is the collusion between Big Pharma, such as Purdue Pharma, Johnson & Johnson, and Endo Pharmaceuticals, academic doctors, professional medical societies, and the FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration).

This strong connection exerts tremendous influence on doctors' prescriptions.

Purdue Pharma, known in particular for its maker of opioid painkillers like OxyContin (an FDA Schedule II controlled substance prescribed for cancer pain), has played a key role in the opioid epidemic in the United States.

These pharmaceutical companies then select doctors whose research findings are favorable to their drugs and provide them with substantial financial support to travel the country presenting their research. These doctors, in turn, often advocate for the widespread and free prescription of opioids.

A prime example is Dr. Russell Potenoy, who had financial ties to at least a dozen pharmaceutical companies (most of which produced prescription opioids) and who spread misinformation about opioids to doctors.

This context explains why doctors have become more proactive in advocating for the liberal use of opioids since the 1980s, unlike before when the prevailing trend was to exercise extreme caution when using opioid painkillers and to avoid long-term prescriptions.

The FDA's responsibility for promoting the commercialization of addictive prescription drugs such as opioids cannot be overlooked either.

As is well known, the FDA is an agency under the Department of Health and Human Services responsible for approving drugs before they are released to the market and continuously monitoring their safety after they are made available to the public.

But the FDA not only failed to stop drug companies from promoting opioids for chronic pain despite a lack of evidence, but also contributed to the prescription opioid painkiller epidemic by making it easier for them to get approval for new opioids they bring to market.

In particular, it provided pharmaceutical companies with preferential treatment by introducing a "screened enrollment" approval system that only included chronic pain patients who already preferred opioids in their studies.

In fact, in 2007, three top executives at Purdue Pharma pleaded guilty to "falsely labeling" OxyContin as less addictive, and Purdue Pharma paid a $634 million fine.

Kentucky, one of the states hardest hit by the prescription opioid epidemic, was the only one to refuse a $500,000 refund and filed its own class action lawsuit against Purdue Pharma, which resulted in a $24 million settlement in 2015 and a further $73.1 million settlement in June 2025, bringing the total to more than $1 billion.

Additionally, the attorneys general of all 50 states and five territories signed a $7.4 billion settlement-in-principle with Purdue Pharma and its owners, the Sackler family, in June 2025 (a multistate settlement), under which states like Illinois and California will receive compensation from Purdue Pharma over a long period of time.

The industrialized medical system is also a problem.

The ongoing epidemic of addictive prescription drugs is not the result of a few deviant doctors intentionally harming patients.

Of course, such doctors exist, but the more fundamental problem is that countless well-meaning doctors work in "medical factories" that prioritize the throughput of specific body parts over the holistic health of their patients.

That is why overprescribing by doctors is so rampant.

Because simply prescribing medication is faster and more financially rewarding than educating or empathizing with patients.

In a system where doctors evaluate their status as professionals based on their ability to generate revenue and patient satisfaction surveys, especially in the case of the "3-minute consultation" that is repeated in Korea, there is a greater risk that doctors will objectify patients as commodities rather than treat them as individuals.

Patients, too, are prone to using doctors as mere drug suppliers.

Is True Addiction Treatment Possible? Beyond the "Drug Addict" Stigma and the Drug Maze

The road to recovery is very slow and arduous compared to the relatively short period of time that addiction develops.

If you're already addicted to a particular drug, what's the best way to stop using it? Since prescription drug addiction itself isn't solely the patient's responsibility or problem, recovery from it requires close communication between the patient and their doctor, along with active social support for treatment.

Above all, it is important to break down the social stigma and perception surrounding drug addiction.

In particular, the attitude of judging and criticizing patients who seek drugs due to addiction as 'malingering' or unconditionally considering addiction itself as moral depravity or sin is the biggest obstacle to addiction treatment.

Although public awareness of the causes of addiction has improved compared to the past, innovation in the medical approach to addiction has not yet been achieved.

Many people still view addiction as simply a lack of willpower.

What makes the problem worse is the reluctance of insurance companies to cover addiction treatment.

While they provide treatment for costly chronic conditions like diabetes and kidney disease, as well as other complex mental health issues, they are unwilling to pay for hospitalization or addiction treatment for patients experiencing opioid withdrawal.

Ultimately, the process of exploring the possibilities of addiction treatment must go beyond treating individual patients and involve understanding the roots and reality of the “hidden forces driving the addiction prescription drug epidemic” and practicing intervention to address them.

Our society must restructure its health care system to publicly acknowledge that the new duty of medicine is to treat not only those with physical illness but also those with mental illness, including addiction.

Today's physicians are faced with the challenge of treating people with increasingly complex biopsychosocial problems (from genetics, upbringing, and environmental factors), yet they are often not given the tools, time, or resources to do so.

As long as the current industrialized, fee-for-service, factory-style healthcare system persists, solving complex mental and behavioral problems like addiction will remain elusive.

Addiction treatment should involve not only physical practices like "drinking" but also healing through relationships and community.

To achieve this, addiction treatment should not remain on the periphery of the medical system as it is now, but should be organically integrated into the overall medical system.

This is also the process by which our society willingly accepts addiction as a 'disease'.

To narrow down the scope of the doctor-patient relationship, sufficient communication and "joint decision-making" are necessary, where the patient is evaluated on the effectiveness and side effects of medications without excluding the patient.

Of course, this would require more consultation time than most medical institutions currently allow doctors.

It is especially important to gradually taper off medication and try 'non-pharmacological therapies', as this opens up opportunities to get away from medication and focus on life.

Activities such as cognitive behavioral therapy, exercise therapy, meditation, yoga, education, and participation in healing communities can help people live their lives in ways other than medication.

It is a process of 'retraining the nervous system' to find new ways to manage pain, and it is also a process of building a common language through sharing experiences between patients and therapists.

“The medicine is similar to a kickboard for beginner swimmers or training wheels for first-time bicycle riders.

The doctor's role is to help people learn to swim and balance on their own without the aid of such tools, rather than making them forever dependent on them.

Psychiatry must prepare for that 'moment of letting go' before it's too late.

“Instead of eliminating pain, we need a new paradigm of treatment that allows us to move through pain and rediscover the meaning of life.” (Translator)

“Problem solving can begin with the realization that it is impossible to escape all the suffering that comes from life.

In other words, we need to change our perspective on stress, discomfort, and pleasure.

The patients featured in this book tell similar stories.

“The stories of people who were only concerned with eliminating pain show that recovery begins only when we face our pain and create meaning for our lives.” (Jeong Hee-won)

The war against addiction is ongoing.

Deceiving doctors and poisoning patients

The true face of the medical system that engulfs us in a vast web

※ Highly recommended by Na Jong-ho (addiction psychiatrist) and Jeong Hee-won (internist) ※

Pain relievers, mood stabilizers, sleeping pills, antidepressants, concentration enhancers… Modern people’s lives are surrounded by various drugs.

From pain relievers prescribed for colds, various inflammations, and muscle pain to various psychiatric medications that alleviate difficult-to-manage mental pain or problems, various medications that act quickly on pain and symptoms greatly improve our quality of life.

The remarkable advancements in medicine and the pharmaceutical industry have ushered in an era where drugs can be consumed as easily and lightly as ordering an espresso.

But what if these "legally and safely" prescribed drugs by doctors actually trap us in the trap of serious addiction? What if "prescription drugs," rather than narcotics or alcohol, lead us to drug dependence and addiction? What if, instead of achieving "treatment," we inflict yet another "disease" and "damage"? In the United States, approximately 16,000 people die from opioid overdoses each year, and South Korea, with its increasing use of "medical narcotics," is also not immune to the risk of death.

The reality of Korean society is that approximately 20.01 million people (4 out of 10 people) have been prescribed medical narcotics at least once (2024 Ministry of Food and Drug Safety statistics).

Anna Lemke, the author of "Dopamine Nation," who received much love from Korean readers, diagnoses the problem of "prescription drug addiction" in "The Addiction Doctors" and continues her sharp insight into its root cause.

How does the distorted medical system work, leading doctors to overprescribe and thus addict patients? Why do we so overestimate the effectiveness of medications and ignore their harmful effects? In this book, the author interviews practicing doctors and his own patients to delve deeply into the background and mechanisms behind this reality.

As those who recommended this book say, "Doctors Who Sell Addiction" is a "desperate warning and earnest request to Korean society and Korean doctors" (Na Jong-ho) beyond the American medical field, and is a masterpiece that "goes beyond pointing out the reality of 'drug addiction' and raises important topics of self-care and self-directed living" (Jeong Hee-won).

The War on Drugs: The Drugs That Fuel Addiction

“We now live in an age where going to the emergency room and getting a shot of Dilaudid (a powerful opioid painkiller containing hydromorphone) or a prescription or two of Klonopin (a benzodiazepine containing clonazepam) is as easy as ordering an espresso.

“It is not the individuals who seek drugs for non-medical purposes who are responsible for these situations, but the system that allows them to happen.” (p. 254)

The author, an addiction psychiatrist with tens of thousands of clinical experiences, analyzes that the background to today's accelerating 'addictive prescription drug epidemic' is that the standard for 'unbearable pain' was lowered to an unprecedented level as the perspective on pain changed in the latter half of the 20th century, and as a result, the prescription and consumption of addictive prescription drugs by patients complaining of physical and mental pain increased.

As the term "prescription drugs" suggests, most patients do not obtain their medications illegally through drug dealers.

They were legally prescribed medication by their doctors, and that's exactly what led them into the trap of addiction.

The lives of such people follow a typical downward curve, being ruined by drugs.

Not only do they lose their jobs, friends, and family, but many end up on the verge of death from opioid overdoses.

The authors also present the case of a patient who was prescribed 1,200 opioid pills by 16 different doctors over several months before being admitted to the hospital.

The author strongly emphasizes that this case is by no means exceptional.

In fact, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) declared a “prescription drug epidemic” on November 1, 2011, and clearly stated that the cause of this epidemic was “opioid painkillers and some psychiatric medications that are being prescribed more widely by doctors.”

“In 2010, for the first time in history, unintentional drug poisonings became the leading cause of death in the United States, surpassing deaths from traffic accidents.

The disaster was widespread and racially insensitive, with the largest increases occurring among white, middle-class people living in rural areas.”

In particular, the younger generation, represented by the millennial generation (born between 1980 and 2000), actively accepted the 'promise of hope' that a better life could be achieved through chemical substances called drugs.

Many young people and teenagers today take addiction to prescription drugs lightly.

In the morning, you take Adderall, a stimulant, to get a feel for yourself; at lunch, you take Vicodin, an opioid painkiller, to treat a workout injury; in the evening, you use "medical" marijuana to relax your mind; and at night, you take Xanax, a benzodiazepine, to help you sleep.

Central nervous system stimulants (psycho-stimulants) taken to improve concentration are often considered nothing more than 'good study aids'.

This reality is not limited to the American reality that the author primarily deals with.

South Korea, which has long been called a "drug-free country," is not much different from the United States.

As author Anna Lemke and translator Chang-Hyeon Jang (Doctors Urge Caution with Addictive Prescription Drugs) unanimously state, “The reality of addictive prescription drug abuse in American society is a warning for Korea’s future.”

This is because many of the factors that promote overprescription in the United States are also at work in Korea.

Although there may be differences depending on the treatment environment, the time for psychiatric outpatient treatment in Korea is relatively short (less than 10 minutes).

Also, as in the US, the more patients seen in a short period of time, the greater the financial compensation (of the doctor).

Korea also tends to be lenient in prescribing drugs that can cause addiction.

In particular, the barriers to prescribing drugs with clear risks of dependence and abuse, such as benzodiazepine anti-anxiety drugs, the sleep aid zolpidem, and the psychostimulant methylphenidate, are low.

Third, Korea still has a weak level of 'shared decision-making.'

Patients and their families are rarely provided with adequate information about the risks, benefits, and alternatives of medications.

How Pain and Psychological Diversity Become Disease: A Culture That Rejects Alternative Narratives

The tendency for both doctors and patients to rely excessively on medication is fundamentally linked to a contemporary culture that rejects alternative disease narratives.

Our contemporary culture stifles diverse lifestyles by labeling pain a “curse to be completely avoided” and various emotional, cognitive, and temperamental differences as “diseases.”

Pain was originally a desirable element of the healing process, but with the advancement of pain treatment in the mid-1850s, it began to be viewed as something to be eliminated, and the result is today's reality where the standard for "unbearable pain" has been lowered to an unprecedented level.

The modern disease narrative, which defines human differences and diversity as illness, also emphasizes only treatments that eliminate such differences.

“If we define human diversity as a disease, we naturally come to the conclusion that we need treatment to eliminate these differences.

This idea is supported by the contemporary view of mental illness, which sees thoughts, feelings, and behaviors as nothing more than the activation of neurons in a chemical soup.

“Modifying brain chemistry has become a new way to normalize differences.”

The author points out the "reverse logic" of his patient Karen, who, after following her friends into taking Adderall to improve her academic focus and experiencing its effects, came to believe (through its effects) that she had ADHD.

This way of thinking, prevalent in the psychiatric community, is that if you take a certain medication and your condition improves, you must be suffering from the disease that the medication is treating.

However, in reality, almost anyone can improve their concentration and performance by taking psychostimulants, even if they do not have ADHD.

We are all born different, mentally and physically.

However, today's society and culture too easily label those differences as diseases and try to treat them with medication.

Karen's case, where she attributed her learning difficulties to a pathological brain problem and began taking psychostimulants for long-term treatment for attention deficit disorder, vividly illustrates this tendency prevalent in our culture.

“Today, mental illness encompasses not only deviant behavior but also subtle differences between individuals.

It is explained as a mental illness not only to be unable to adapt to something, but also to not be able to show outstanding abilities.

“Therefore, now even students with below-average learning abilities or unique recluse individuals are at risk of being diagnosed with a mental illness.” (p. 118)

Of course, for some people, being diagnosed with a mental illness can help clear their doubts.

This can provide access to resources that might otherwise be unavailable and a framework for understanding one's differences, potentially freeing one from stigma and shame.

What is really problematic is the hasty approach of going beyond simply diagnosing the differences and trying to 'cure' them with a 'magic pill'.

You must be especially careful when the drug carries a risk of addiction.

“Doctors, especially psychiatrists, are largely responsible for the prevalence of this approach.

“Over the past 30 years, psychiatrists have increasingly relied on psychoactive drugs to treat patients’ emotional distress, psychiatric symptoms, or life crises, leaving psychotherapy to others.” (p. 119)

Big Drug Cartels and Medical Mills: The Healthcare System That Fuels Drug Abuse

So why do psychiatrists so readily abandon psychoanalysis and other talk therapies in favor of "magic pills"? Why do even doctors allow patients to become dependent on prescription medications, or why do they often overlook the risks of medications? We might rephrase this question this way.

What makes well-intentioned efforts and sincerity to improve the lives of those suffering from pain ineffective? Behind this reality lies a corrupt medical system, and "Doctors Who Sell Addiction" closely examines this system.

"This book painfully demonstrates how devastating the consequences can be when doctors' desire to alleviate patients' pain combines with their ignorance about addiction in a corrupt system." (Na Jong-ho)

In the case of the United States, which has already suffered from the pain of the 'addictive prescription drug epidemic', efforts are being made to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past, such as introducing Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs) and allowing doctors to check online which controlled substances (benzodiazepines, ADHD medications, opioid drugs, etc.) patients have been prescribed.

However, it can be said that American society, as well as Korean society, is still fighting a 'war on drugs', because it is not easy to bring about change within a structurally sick system.

Moreover, the existence of patients who suffer from various complications due to drug addiction, suffer irreversible damage, and even die further highlights the seriousness of this problem.

What distorts and corrupts the healthcare system is the collusion between Big Pharma, such as Purdue Pharma, Johnson & Johnson, and Endo Pharmaceuticals, academic doctors, professional medical societies, and the FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration).

This strong connection exerts tremendous influence on doctors' prescriptions.

Purdue Pharma, known in particular for its maker of opioid painkillers like OxyContin (an FDA Schedule II controlled substance prescribed for cancer pain), has played a key role in the opioid epidemic in the United States.

These pharmaceutical companies then select doctors whose research findings are favorable to their drugs and provide them with substantial financial support to travel the country presenting their research. These doctors, in turn, often advocate for the widespread and free prescription of opioids.

A prime example is Dr. Russell Potenoy, who had financial ties to at least a dozen pharmaceutical companies (most of which produced prescription opioids) and who spread misinformation about opioids to doctors.

This context explains why doctors have become more proactive in advocating for the liberal use of opioids since the 1980s, unlike before when the prevailing trend was to exercise extreme caution when using opioid painkillers and to avoid long-term prescriptions.

The FDA's responsibility for promoting the commercialization of addictive prescription drugs such as opioids cannot be overlooked either.

As is well known, the FDA is an agency under the Department of Health and Human Services responsible for approving drugs before they are released to the market and continuously monitoring their safety after they are made available to the public.

But the FDA not only failed to stop drug companies from promoting opioids for chronic pain despite a lack of evidence, but also contributed to the prescription opioid painkiller epidemic by making it easier for them to get approval for new opioids they bring to market.

In particular, it provided pharmaceutical companies with preferential treatment by introducing a "screened enrollment" approval system that only included chronic pain patients who already preferred opioids in their studies.

In fact, in 2007, three top executives at Purdue Pharma pleaded guilty to "falsely labeling" OxyContin as less addictive, and Purdue Pharma paid a $634 million fine.

Kentucky, one of the states hardest hit by the prescription opioid epidemic, was the only one to refuse a $500,000 refund and filed its own class action lawsuit against Purdue Pharma, which resulted in a $24 million settlement in 2015 and a further $73.1 million settlement in June 2025, bringing the total to more than $1 billion.

Additionally, the attorneys general of all 50 states and five territories signed a $7.4 billion settlement-in-principle with Purdue Pharma and its owners, the Sackler family, in June 2025 (a multistate settlement), under which states like Illinois and California will receive compensation from Purdue Pharma over a long period of time.

The industrialized medical system is also a problem.

The ongoing epidemic of addictive prescription drugs is not the result of a few deviant doctors intentionally harming patients.

Of course, such doctors exist, but the more fundamental problem is that countless well-meaning doctors work in "medical factories" that prioritize the throughput of specific body parts over the holistic health of their patients.

That is why overprescribing by doctors is so rampant.

Because simply prescribing medication is faster and more financially rewarding than educating or empathizing with patients.

In a system where doctors evaluate their status as professionals based on their ability to generate revenue and patient satisfaction surveys, especially in the case of the "3-minute consultation" that is repeated in Korea, there is a greater risk that doctors will objectify patients as commodities rather than treat them as individuals.

Patients, too, are prone to using doctors as mere drug suppliers.

Is True Addiction Treatment Possible? Beyond the "Drug Addict" Stigma and the Drug Maze

The road to recovery is very slow and arduous compared to the relatively short period of time that addiction develops.

If you're already addicted to a particular drug, what's the best way to stop using it? Since prescription drug addiction itself isn't solely the patient's responsibility or problem, recovery from it requires close communication between the patient and their doctor, along with active social support for treatment.

Above all, it is important to break down the social stigma and perception surrounding drug addiction.

In particular, the attitude of judging and criticizing patients who seek drugs due to addiction as 'malingering' or unconditionally considering addiction itself as moral depravity or sin is the biggest obstacle to addiction treatment.

Although public awareness of the causes of addiction has improved compared to the past, innovation in the medical approach to addiction has not yet been achieved.

Many people still view addiction as simply a lack of willpower.

What makes the problem worse is the reluctance of insurance companies to cover addiction treatment.

While they provide treatment for costly chronic conditions like diabetes and kidney disease, as well as other complex mental health issues, they are unwilling to pay for hospitalization or addiction treatment for patients experiencing opioid withdrawal.

Ultimately, the process of exploring the possibilities of addiction treatment must go beyond treating individual patients and involve understanding the roots and reality of the “hidden forces driving the addiction prescription drug epidemic” and practicing intervention to address them.

Our society must restructure its health care system to publicly acknowledge that the new duty of medicine is to treat not only those with physical illness but also those with mental illness, including addiction.

Today's physicians are faced with the challenge of treating people with increasingly complex biopsychosocial problems (from genetics, upbringing, and environmental factors), yet they are often not given the tools, time, or resources to do so.

As long as the current industrialized, fee-for-service, factory-style healthcare system persists, solving complex mental and behavioral problems like addiction will remain elusive.

Addiction treatment should involve not only physical practices like "drinking" but also healing through relationships and community.

To achieve this, addiction treatment should not remain on the periphery of the medical system as it is now, but should be organically integrated into the overall medical system.

This is also the process by which our society willingly accepts addiction as a 'disease'.

To narrow down the scope of the doctor-patient relationship, sufficient communication and "joint decision-making" are necessary, where the patient is evaluated on the effectiveness and side effects of medications without excluding the patient.

Of course, this would require more consultation time than most medical institutions currently allow doctors.

It is especially important to gradually taper off medication and try 'non-pharmacological therapies', as this opens up opportunities to get away from medication and focus on life.

Activities such as cognitive behavioral therapy, exercise therapy, meditation, yoga, education, and participation in healing communities can help people live their lives in ways other than medication.

It is a process of 'retraining the nervous system' to find new ways to manage pain, and it is also a process of building a common language through sharing experiences between patients and therapists.

“The medicine is similar to a kickboard for beginner swimmers or training wheels for first-time bicycle riders.

The doctor's role is to help people learn to swim and balance on their own without the aid of such tools, rather than making them forever dependent on them.

Psychiatry must prepare for that 'moment of letting go' before it's too late.

“Instead of eliminating pain, we need a new paradigm of treatment that allows us to move through pain and rediscover the meaning of life.” (Translator)

“Problem solving can begin with the realization that it is impossible to escape all the suffering that comes from life.

In other words, we need to change our perspective on stress, discomfort, and pleasure.

The patients featured in this book tell similar stories.

“The stories of people who were only concerned with eliminating pain show that recovery begins only when we face our pain and create meaning for our lives.” (Jeong Hee-won)

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: November 17, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 332 pages | 422g | 136*206*20mm

- ISBN13: 9791168731660

- ISBN10: 1168731666

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)