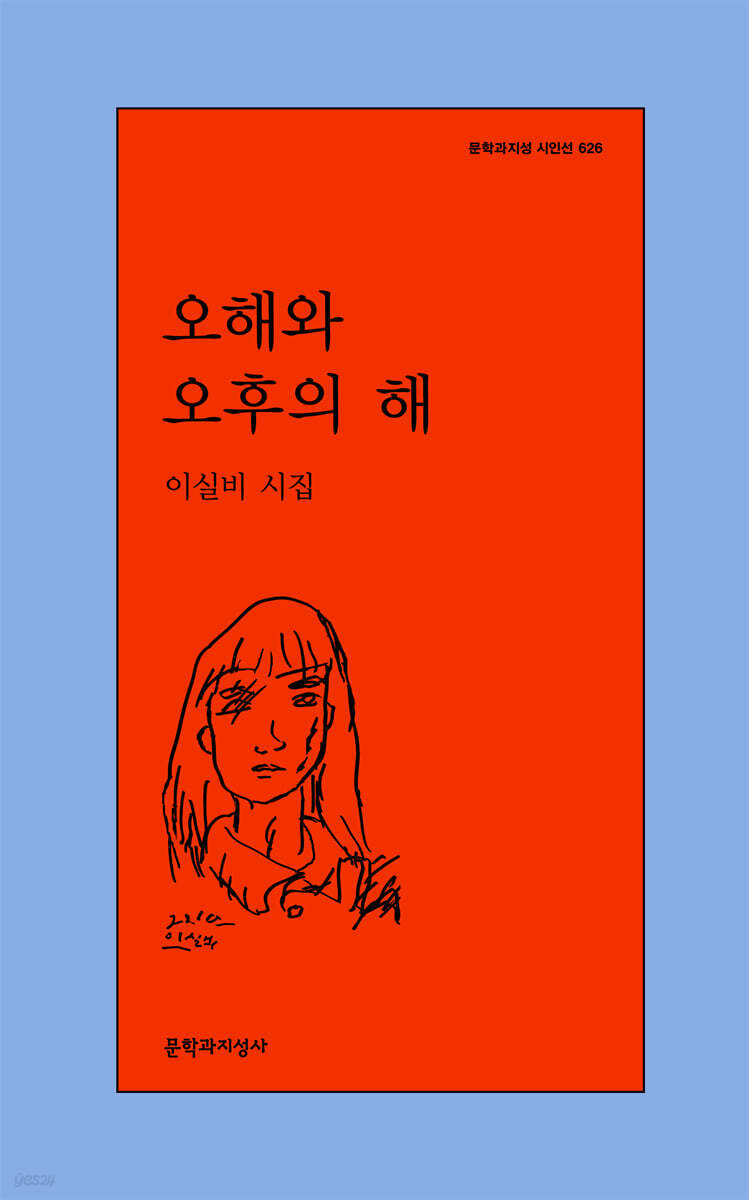

Misunderstanding and the Afternoon Sun

|

Description

Book Introduction

“I sat in a dark room for a long time.”

A screen of love illuminating the pouring darkness

Rewriting the future by staring at the blank space

Isilbi's first poetry collection explores the age of enduring suffering.

Poet Lee Sil-bi, who began her career through the 2024 Seoul Shinmun New Year's Literary Contest, has published her first poetry collection, Misunderstanding and the Afternoon Sun, as the 626th issue of the Munhak-kwa-Jisung Poet Selection.

At the time of his debut, the poet, who received high expectations from critics, received reviews such as “an overwhelming work with skillful and exquisite image arrangement and development” and “a portrait of our times that gathers death, love, anxiety, and loneliness into shadowy images behind the theater and implicitly conveys them” (Hwang In-chan, Kim So-yeon, Park Yeon-jun, 2024 Seoul Shinmun New Year’s Literary Contest Judges’ Comments), and is currently actively working, demonstrating “a remarkable talent for organizing the various conflicting imaginary time differences into a single space” (Lee Su-myeong, Recommendation for Poetry 2025).

It immediately captivates readers with its dense composition, summarized by the intersection of intense color images, narrative space, and fast-paced development of the poem.

The book is divided into four parts and contains 50 poems written with tenacious breathing, showcasing variations of original images.

When I'm at the end of a row of people whose names, ages, and faces I don't know, my pain no longer feels like my own, nor does theirs feel like theirs.

[… … ] This collection of poems proves the interconnectedness of images through a sophisticated arrangement of images without prioritizing emotions or justification, and is therefore unique and persuasive.

─Song Hyun-ji, commentary on “The Anthropology of Pain”

A screen of love illuminating the pouring darkness

Rewriting the future by staring at the blank space

Isilbi's first poetry collection explores the age of enduring suffering.

Poet Lee Sil-bi, who began her career through the 2024 Seoul Shinmun New Year's Literary Contest, has published her first poetry collection, Misunderstanding and the Afternoon Sun, as the 626th issue of the Munhak-kwa-Jisung Poet Selection.

At the time of his debut, the poet, who received high expectations from critics, received reviews such as “an overwhelming work with skillful and exquisite image arrangement and development” and “a portrait of our times that gathers death, love, anxiety, and loneliness into shadowy images behind the theater and implicitly conveys them” (Hwang In-chan, Kim So-yeon, Park Yeon-jun, 2024 Seoul Shinmun New Year’s Literary Contest Judges’ Comments), and is currently actively working, demonstrating “a remarkable talent for organizing the various conflicting imaginary time differences into a single space” (Lee Su-myeong, Recommendation for Poetry 2025).

It immediately captivates readers with its dense composition, summarized by the intersection of intense color images, narrative space, and fast-paced development of the poem.

The book is divided into four parts and contains 50 poems written with tenacious breathing, showcasing variations of original images.

When I'm at the end of a row of people whose names, ages, and faces I don't know, my pain no longer feels like my own, nor does theirs feel like theirs.

[… … ] This collection of poems proves the interconnectedness of images through a sophisticated arrangement of images without prioritizing emotions or justification, and is therefore unique and persuasive.

─Song Hyun-ji, commentary on “The Anthropology of Pain”

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Poet's words

Part 1: Soft and Strange

Stone in the water

locals

Seoul Wolf

Anchovies and naps

White and soft sleep

consolation

Lighting room

date

Your friend the traitor

My friend the executioner

The fall of the empire

Part 2: The things I love pass by at the speed of love.

break

Accommodation

bullet

riverbank

replication

outing

deep waters

buoy

Wolgok

Peony

knee

jean

Last summer's sweet

Part 3 I want to starve my face in the dark

Free

free

The violence I know

Misunderstanding and the Afternoon Sun

home

pickling

They said I was crazy

seven

From the cliff to the chicken coop

Tulip Festival

Ears and bells

Three excerpts from the villa in Part 4

taxi

villa

magazine

librarian

rooftop

name

Marsh

tunnel

windmill

taxi

letter

letter

succession

plum

journal

commentary

The Anthropology of Pain: Song Hyeon-ji

Part 1: Soft and Strange

Stone in the water

locals

Seoul Wolf

Anchovies and naps

White and soft sleep

consolation

Lighting room

date

Your friend the traitor

My friend the executioner

The fall of the empire

Part 2: The things I love pass by at the speed of love.

break

Accommodation

bullet

riverbank

replication

outing

deep waters

buoy

Wolgok

Peony

knee

jean

Last summer's sweet

Part 3 I want to starve my face in the dark

Free

free

The violence I know

Misunderstanding and the Afternoon Sun

home

pickling

They said I was crazy

seven

From the cliff to the chicken coop

Tulip Festival

Ears and bells

Three excerpts from the villa in Part 4

taxi

villa

magazine

librarian

rooftop

name

Marsh

tunnel

windmill

taxi

letter

letter

succession

plum

journal

commentary

The Anthropology of Pain: Song Hyeon-ji

Into the book

What hurts you is

Like eyes that try to remember every afternoon in the world

A stone in the water that tosses and turns and sinks

A person who knows how to speak without crying walks into the water.

--- From "Stone in the Water"

Why is that happening? If I keep doing that, won't my pillow fall out and I'll be cold in the morning?

I was going to ask

just

I decided to go buy some red bean buns with him in the morning.

When I tear it in half, I decide to share the darkness that pours down wetly.

--- From "White and Soft Sleep"

After the movie ended

You said you knew what was on his mind.

I feel like I will never know the heart of the blue tree.

We had a fight.

Why do we so easily project ourselves onto such things?

Why suffer when you project it?

There has never been a day when I was so desperate to know your heart.

--- From "Last Summer's Dan"

I want to be happy.

I want to be happy with you for a long time.

I don't wave anything at you and you don't call me any derogatory names.

I want to laugh in the farthest place from violence.

The greatest violence committed every day by that desire to laugh.

--- From "The Violence I Know"

But you're not interested in your own story anymore, you think your despair can't be special.

What makes you special is that you can smile, that you are willing to give up your heart for a bird, that you try to understand the person who abandoned you, and that you tell me all of that without me having to ask.

I want to keep talking

Like eyes that try to remember every afternoon in the world

A stone in the water that tosses and turns and sinks

A person who knows how to speak without crying walks into the water.

--- From "Stone in the Water"

Why is that happening? If I keep doing that, won't my pillow fall out and I'll be cold in the morning?

I was going to ask

just

I decided to go buy some red bean buns with him in the morning.

When I tear it in half, I decide to share the darkness that pours down wetly.

--- From "White and Soft Sleep"

After the movie ended

You said you knew what was on his mind.

I feel like I will never know the heart of the blue tree.

We had a fight.

Why do we so easily project ourselves onto such things?

Why suffer when you project it?

There has never been a day when I was so desperate to know your heart.

--- From "Last Summer's Dan"

I want to be happy.

I want to be happy with you for a long time.

I don't wave anything at you and you don't call me any derogatory names.

I want to laugh in the farthest place from violence.

The greatest violence committed every day by that desire to laugh.

--- From "The Violence I Know"

But you're not interested in your own story anymore, you think your despair can't be special.

What makes you special is that you can smile, that you are willing to give up your heart for a bird, that you try to understand the person who abandoned you, and that you tell me all of that without me having to ask.

I want to keep talking

--- From "Plum"

Publisher's Review

After a day of heart-burning misunderstandings

Love Rewritten Behind the Darkness

If this is hell

The backs of the audience's heads in a row

They won't see me

Still I'm watching

I count without forgetting

―「Lighting Room」 section

The speaker of Isilbi's poem, who says, "When I look into the eyes of a dog that believes in love/What I feel is fear," stares at the bleak landscape of love for a long time, but instead of staying in one place, he runs.

This unique speaker, whose body moves through time while aiming at the 'pain of love', sometimes mercilessly hits the nail on the head with the secrets that shake life.

“Let’s not laugh, we’re not dogs/Instead, let’s run really fast,” he whispers, sharing his life in Seoul with the ‘wolf’, who seems out of place in the middle of Seoul.

The times they shared were like a tragedy unfolding on a makeshift stage, irreversible, yet they cast a deep afterimage on their minds.

The speaker, left alone after sending the wolf away, “opens his mouth and laughs like a dog” (“Seoul Wolf”).

The tragedy of love that comes as an unintended consequence.

The 'I' who is swept up in the fear of keeping a distance and exists as fear itself is, in other words, someone who has experienced love and has come to believe in love.

The speaker, who encounters the face of someone who delivers news of someone else's death while eating tteokbokki without stopping, feels a strange beauty and a sense of love, and looks with pity at the sadness of people who continue as they wait for the end.

Sitting in the lighting room, he is aware of the emergency exit lights that “clearly illuminate the interior of the theater,” and by “counting without forgetting the back of others’ heads” (from “Lighting Room”) at the back of hell, he feels that he is “alive.”

At the same time, others also find a way out of hell in their lives and pray for a way to reach the future.

These two impressive poems, included in the poet's debut work and the first part of her poetry collection, clearly demonstrate the thematic awareness that permeates Isilbi's poetic world.

After experiencing separation and loss and embracing loneliness, the speaker leaves the world “just like that/just as it is” and accepts the state of the world as “seeing (revelation)”, and also witnesses unexpected sights.

The narrator, observing the lovers “starting to argue” in a café, sees the hand of one raised above the other’s head, quietly “stroking” (from “Date”) instead of committing violence.

In this way, you realize that anxiety can sometimes escape through a bright exit.

However, since “some beliefs about love end up being useless” (“Your Friend’s Betrayer”), the desire to “show the still/beautiful interior” (“My Friend’s Executioner”) to a friend who does not ride the swing “in the house with the swing” for fear that someone might “stab” her from behind also continues.

In the hospital lobby, while adults comfort each other with vague words like “everything will be okay,” we also see the calves of children “quietly and surely” (“The Fall of an Empire”) bruised as they fight their own battles, “having fun moving between chairs without their mothers knowing.”

Lee Sil-bi's poetry clearly senses the scars each being carries, and does not end with simple affection and comfort.

As we read in the verse, “Some poems come in the morning, some music is more shocking when heard at noon, so the shock must be allowed to flow,” Lee Sil-bi’s poetry is written not as a sentimental way to bleach the darkness of the heart, but as a way to “wonder about it until morning” (“Damage”).

The blank space left for the answer becomes a passage through which many confessions can flow in and out, and a place where the reader can speak out.

In "Peony," the "alien" who "loses a palm every time he holds someone else's hand" learns the essence of love through the process of losing himself.

The alien calls itself “Peony” through the confession that “I wanted to hold hands with those who can willingly drop the remaining petals one by one” even after dropping most of the petals with hands full of passion, unable to let go of the peony, which is like a medicine that heals wounds or the name of a loved one.

Isilbi's poetry exquisitely captures the uncontrollable, unstoppable nature of love, while portraying the painful encounter between existences.

At the same time, the poet focuses on the possibility of change brought about by the active movement (or movement) of the subject.

The future of love cannot be experienced “with both feet together.”

In front of the black lake, the speaker is afraid that 'you' will be sucked into the water, and at the same time, he feels fear as he looks at the duck egg that has "popped into" the lake.

The speaker, whose ankles were bitten by ducks hatched from eggs, continues to move forward “blowing on his cracked knees” (“Knees”) toward “you,” who is standing on the ground “with frozen toes” and “only my own heart aches.”

However, even 'you' who welcomed the speaker ends up submerged in water and having your feet bitten by a flock of ducks.

The question from 'I' to 'you', who also lost her foot but ended up leaving the cold ground, "How are you? Does it not hurt at all?" sharply points out that communication of love is not achieved through mutual fulfillment, but through empathizing with the other person's pain on the same level as them.

Also, as seen in the last poem of Part 2, “Last Summer’s Dan,” there are conflicting feelings even after going through the same experience, and the speaker of Isilbi’s poem confirms that “I cannot choose what you want to look closely at,” and does not miss the selfish and cruel side of love, where “things I love” “pass by at the speed of loving me” rather than at the speed of “my” love.

A tunnel of violence and twisted love

An unfinished letter arrived in a hurry

The weeping man thought, If I could build a nest in the sea, If the waterways that gathered one by one from the high mountains became lines, If they tangled and crouched for each other, If the water nest that would float like a buoy If I could put the last piece of sun inside it

The sun will not be grateful

just

It will cool down slowly

―Excerpt from “Misunderstanding and the Afternoon Sun”

Isilbi's poetry explores the darkness brought about by love, unraveling the ever-changing and complex nature of love.

In Part 3, the poet depicts the repeated misunderstandings and controlled personal freedom through a variety of variations of images.

Trapped in the mindset of a “mad person” who interprets the expression of people who say “that’s crazy” when they see a cute baby, the image of “I” who mistakes even the antics of a mad person for people “admiring” them because they are “beautiful” (“They Said I’m Crazy”) makes the reader experience an eerie feeling.

A mind blinded by love causes confusion and separates the speaker from the world.

A new face discovered after experiencing constraints and violence, and realizing that “every branch that stretches out haphazardly points to something different” (“Assumption”), and that “the things I wanted to understand were standing behind me/with tens of thousands of fingers spread out, ready to push me over” (“Chil”).

The speaker, who is riding in a taxi, sees a 'mannequin' in the distance.

When my face overlaps with the face of the mannequin trapped in the dressing room, the feeling that “all the pain in the world is connected” (“Ear and Bell”) comes back to life, and the “clock pin” that had held the self in place falls off.

In this way, Isilbi's poem enters the tunnel, dreaming of change.

In Part 4, the narrator goes back to his childhood.

“Sometimes I saw it as if I was glancing out the window,” “being able to stand in one place with my arms outstretched and nothing on.”

The young narrator dreams of becoming a windmill, but is abandoned in a taxi that is not even home, and is full of violence, and ends up in an unfamiliar villa with his younger brother.

There is a 'librarian' there.

While being raised by a librarian who “likes to tell the truth” (from “Rooftop”), he grows up through countless questions.

Following the librarian's wishes that "my brother and I must go out of the villa someday" ("Name"), the narrator drives an abandoned taxi and leaves the city.

The mother, who has parted ways with the resolution that “from now on, I will live a life without learning anything/,” her determination that “I can just go find it” (“Tunnel”) foreshadows the birth of a strong poetic subject.

The belief that if you fill a taxi with stolen letters and cut out the “most important sentences” with a knife and deliver them, the recipient will be grateful because “they can wait for the next words.”

The speaker hopes that the “one of the kindest sentences” (from “Diary”) he cut out will be rewritten by the recipient of the letter, and hopes that he too will receive a letter someday.

The movement of this collection of poems, in which the author, after experiencing excruciating growing pains and realizing the true nature of love, hands over a letter that leaves a portion in the hands of others, resonates deeply enough to be heartbreaking.

As Song Hyeon-ji, who commented on the anthology, puts it, Lee Sil-bi “reveals our inevitable fate of not being able to fully see the pain of others, while also establishing an ethical space where we do not infringe upon each other’s pain.”

The 'diary' of the librarian that raised the soul of the speaker crushed by pain is none other than poetry (literature).

A safe zone that protects tears and provides an exit called 'emptiness' for those who cling to life by leaning on the graves of the dead until they escape hell.

“Who first started believing that books would protect us?” (Plum).

The poet's prose

As a child, I used to open my ears and create a large parking lot.

Your face, held in place by a pin, tears never flowed

The first parking lot you lent me

I waited with my whole body spread out like a crossroads

awe

fear

But finally, pins are falling from your face

The day you got out of the taxi

The drops of blood that were on your round cheeks

I saw threads sticking out between them.

I am you

I realized that things aren't like they were in your childhood anymore.

Poet's words

Because I want to look into your words and heart clearly

I stood all day in broad daylight.

But the skin of the words and the heart will only turn black

I knew what I wanted wasn't close to the light

The time that passed wasted on misunderstandings that were properly avoided

Painful and intimate

And I never want to repeat it again

October 2025

Isilbi

Love Rewritten Behind the Darkness

If this is hell

The backs of the audience's heads in a row

They won't see me

Still I'm watching

I count without forgetting

―「Lighting Room」 section

The speaker of Isilbi's poem, who says, "When I look into the eyes of a dog that believes in love/What I feel is fear," stares at the bleak landscape of love for a long time, but instead of staying in one place, he runs.

This unique speaker, whose body moves through time while aiming at the 'pain of love', sometimes mercilessly hits the nail on the head with the secrets that shake life.

“Let’s not laugh, we’re not dogs/Instead, let’s run really fast,” he whispers, sharing his life in Seoul with the ‘wolf’, who seems out of place in the middle of Seoul.

The times they shared were like a tragedy unfolding on a makeshift stage, irreversible, yet they cast a deep afterimage on their minds.

The speaker, left alone after sending the wolf away, “opens his mouth and laughs like a dog” (“Seoul Wolf”).

The tragedy of love that comes as an unintended consequence.

The 'I' who is swept up in the fear of keeping a distance and exists as fear itself is, in other words, someone who has experienced love and has come to believe in love.

The speaker, who encounters the face of someone who delivers news of someone else's death while eating tteokbokki without stopping, feels a strange beauty and a sense of love, and looks with pity at the sadness of people who continue as they wait for the end.

Sitting in the lighting room, he is aware of the emergency exit lights that “clearly illuminate the interior of the theater,” and by “counting without forgetting the back of others’ heads” (from “Lighting Room”) at the back of hell, he feels that he is “alive.”

At the same time, others also find a way out of hell in their lives and pray for a way to reach the future.

These two impressive poems, included in the poet's debut work and the first part of her poetry collection, clearly demonstrate the thematic awareness that permeates Isilbi's poetic world.

After experiencing separation and loss and embracing loneliness, the speaker leaves the world “just like that/just as it is” and accepts the state of the world as “seeing (revelation)”, and also witnesses unexpected sights.

The narrator, observing the lovers “starting to argue” in a café, sees the hand of one raised above the other’s head, quietly “stroking” (from “Date”) instead of committing violence.

In this way, you realize that anxiety can sometimes escape through a bright exit.

However, since “some beliefs about love end up being useless” (“Your Friend’s Betrayer”), the desire to “show the still/beautiful interior” (“My Friend’s Executioner”) to a friend who does not ride the swing “in the house with the swing” for fear that someone might “stab” her from behind also continues.

In the hospital lobby, while adults comfort each other with vague words like “everything will be okay,” we also see the calves of children “quietly and surely” (“The Fall of an Empire”) bruised as they fight their own battles, “having fun moving between chairs without their mothers knowing.”

Lee Sil-bi's poetry clearly senses the scars each being carries, and does not end with simple affection and comfort.

As we read in the verse, “Some poems come in the morning, some music is more shocking when heard at noon, so the shock must be allowed to flow,” Lee Sil-bi’s poetry is written not as a sentimental way to bleach the darkness of the heart, but as a way to “wonder about it until morning” (“Damage”).

The blank space left for the answer becomes a passage through which many confessions can flow in and out, and a place where the reader can speak out.

In "Peony," the "alien" who "loses a palm every time he holds someone else's hand" learns the essence of love through the process of losing himself.

The alien calls itself “Peony” through the confession that “I wanted to hold hands with those who can willingly drop the remaining petals one by one” even after dropping most of the petals with hands full of passion, unable to let go of the peony, which is like a medicine that heals wounds or the name of a loved one.

Isilbi's poetry exquisitely captures the uncontrollable, unstoppable nature of love, while portraying the painful encounter between existences.

At the same time, the poet focuses on the possibility of change brought about by the active movement (or movement) of the subject.

The future of love cannot be experienced “with both feet together.”

In front of the black lake, the speaker is afraid that 'you' will be sucked into the water, and at the same time, he feels fear as he looks at the duck egg that has "popped into" the lake.

The speaker, whose ankles were bitten by ducks hatched from eggs, continues to move forward “blowing on his cracked knees” (“Knees”) toward “you,” who is standing on the ground “with frozen toes” and “only my own heart aches.”

However, even 'you' who welcomed the speaker ends up submerged in water and having your feet bitten by a flock of ducks.

The question from 'I' to 'you', who also lost her foot but ended up leaving the cold ground, "How are you? Does it not hurt at all?" sharply points out that communication of love is not achieved through mutual fulfillment, but through empathizing with the other person's pain on the same level as them.

Also, as seen in the last poem of Part 2, “Last Summer’s Dan,” there are conflicting feelings even after going through the same experience, and the speaker of Isilbi’s poem confirms that “I cannot choose what you want to look closely at,” and does not miss the selfish and cruel side of love, where “things I love” “pass by at the speed of loving me” rather than at the speed of “my” love.

A tunnel of violence and twisted love

An unfinished letter arrived in a hurry

The weeping man thought, If I could build a nest in the sea, If the waterways that gathered one by one from the high mountains became lines, If they tangled and crouched for each other, If the water nest that would float like a buoy If I could put the last piece of sun inside it

The sun will not be grateful

just

It will cool down slowly

―Excerpt from “Misunderstanding and the Afternoon Sun”

Isilbi's poetry explores the darkness brought about by love, unraveling the ever-changing and complex nature of love.

In Part 3, the poet depicts the repeated misunderstandings and controlled personal freedom through a variety of variations of images.

Trapped in the mindset of a “mad person” who interprets the expression of people who say “that’s crazy” when they see a cute baby, the image of “I” who mistakes even the antics of a mad person for people “admiring” them because they are “beautiful” (“They Said I’m Crazy”) makes the reader experience an eerie feeling.

A mind blinded by love causes confusion and separates the speaker from the world.

A new face discovered after experiencing constraints and violence, and realizing that “every branch that stretches out haphazardly points to something different” (“Assumption”), and that “the things I wanted to understand were standing behind me/with tens of thousands of fingers spread out, ready to push me over” (“Chil”).

The speaker, who is riding in a taxi, sees a 'mannequin' in the distance.

When my face overlaps with the face of the mannequin trapped in the dressing room, the feeling that “all the pain in the world is connected” (“Ear and Bell”) comes back to life, and the “clock pin” that had held the self in place falls off.

In this way, Isilbi's poem enters the tunnel, dreaming of change.

In Part 4, the narrator goes back to his childhood.

“Sometimes I saw it as if I was glancing out the window,” “being able to stand in one place with my arms outstretched and nothing on.”

The young narrator dreams of becoming a windmill, but is abandoned in a taxi that is not even home, and is full of violence, and ends up in an unfamiliar villa with his younger brother.

There is a 'librarian' there.

While being raised by a librarian who “likes to tell the truth” (from “Rooftop”), he grows up through countless questions.

Following the librarian's wishes that "my brother and I must go out of the villa someday" ("Name"), the narrator drives an abandoned taxi and leaves the city.

The mother, who has parted ways with the resolution that “from now on, I will live a life without learning anything/,” her determination that “I can just go find it” (“Tunnel”) foreshadows the birth of a strong poetic subject.

The belief that if you fill a taxi with stolen letters and cut out the “most important sentences” with a knife and deliver them, the recipient will be grateful because “they can wait for the next words.”

The speaker hopes that the “one of the kindest sentences” (from “Diary”) he cut out will be rewritten by the recipient of the letter, and hopes that he too will receive a letter someday.

The movement of this collection of poems, in which the author, after experiencing excruciating growing pains and realizing the true nature of love, hands over a letter that leaves a portion in the hands of others, resonates deeply enough to be heartbreaking.

As Song Hyeon-ji, who commented on the anthology, puts it, Lee Sil-bi “reveals our inevitable fate of not being able to fully see the pain of others, while also establishing an ethical space where we do not infringe upon each other’s pain.”

The 'diary' of the librarian that raised the soul of the speaker crushed by pain is none other than poetry (literature).

A safe zone that protects tears and provides an exit called 'emptiness' for those who cling to life by leaning on the graves of the dead until they escape hell.

“Who first started believing that books would protect us?” (Plum).

The poet's prose

As a child, I used to open my ears and create a large parking lot.

Your face, held in place by a pin, tears never flowed

The first parking lot you lent me

I waited with my whole body spread out like a crossroads

awe

fear

But finally, pins are falling from your face

The day you got out of the taxi

The drops of blood that were on your round cheeks

I saw threads sticking out between them.

I am you

I realized that things aren't like they were in your childhood anymore.

Poet's words

Because I want to look into your words and heart clearly

I stood all day in broad daylight.

But the skin of the words and the heart will only turn black

I knew what I wanted wasn't close to the light

The time that passed wasted on misunderstandings that were properly avoided

Painful and intimate

And I never want to repeat it again

October 2025

Isilbi

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: October 24, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 164 pages | 230g | 128*205*13mm

- ISBN13: 9788932044651

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)