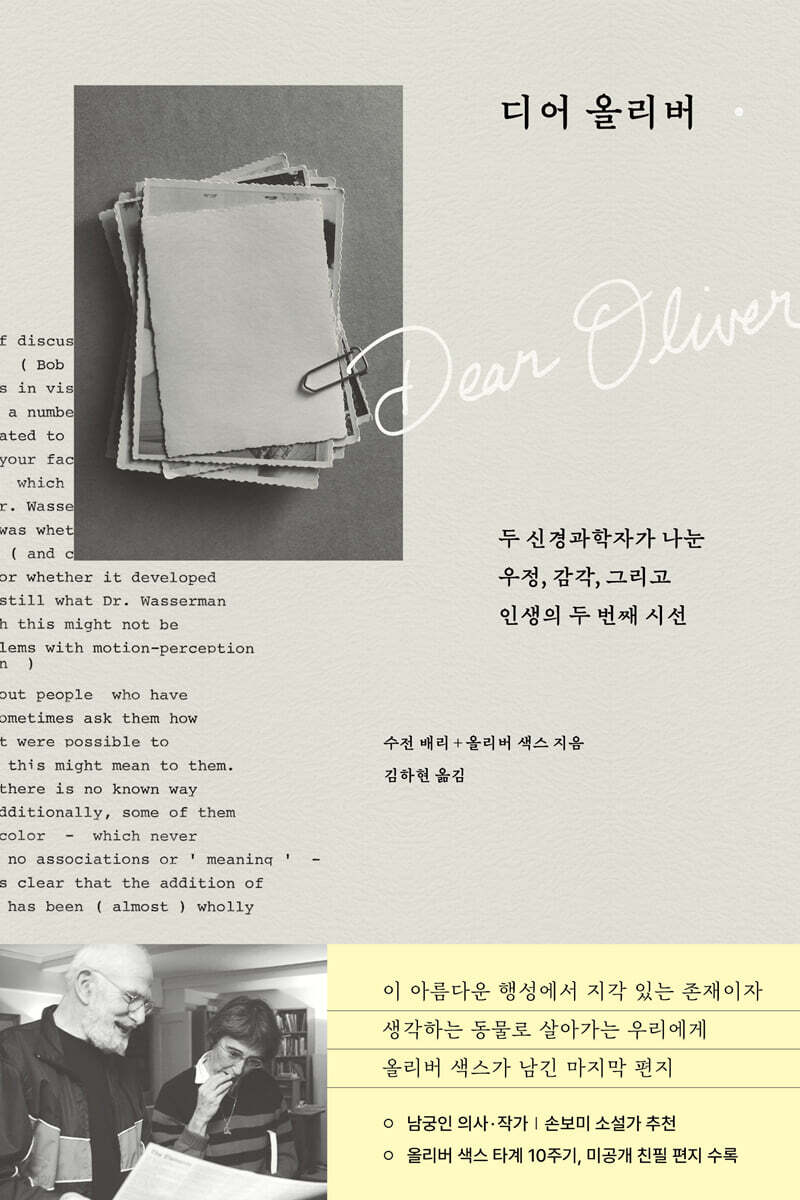

Dear Oliver

|

Description

Book Introduction

Oliver Sacks, a physician and neurologist who generously poured his genius into helping the vulnerable beings the world considered insignificant, and the world-beloved "poet of medicine,"

The last letter he left behind has arrived before us now, ten years after his death.

The recipient of the letter is neurobiologist Susan Barry, who lived with stereopsis and astigmatism for half her life before finally seeing the world in stereo at the age of forty-eight.

Their conversation, which began when Susan wrote down her wondrous visual experience and continued until Oliver's eyes closed.

However, in the winter of that year, when Oliver responded to Susan's first letter and their friendship blossomed, Oliver was diagnosed with ocular melanoma and began to lose his vision.

While one person opens his eyes to a new world he has never experienced before, the other person loses his familiar world.

Nevertheless, Oliver watched Susan's joy and delight and did not spare encouragement and support so that she could write a book.

Susan, heartbroken by the fact that she could do nothing to help Oliver, refused to be consumed by her grief and instead came up with an idea to comfort him.

Both men firmly believed in human neuroplasticity and the power of recovery, and they maintained their courage and humor until the very end.

"Dear Oliver" is a collection of letters between two neuroscientists who exchanged over 150 letters over a period of ten years, teaching each other to see the world differently. It is also a memoir written by one who is now left alone, remembering and missing the one who has passed away.

The last letter he left behind has arrived before us now, ten years after his death.

The recipient of the letter is neurobiologist Susan Barry, who lived with stereopsis and astigmatism for half her life before finally seeing the world in stereo at the age of forty-eight.

Their conversation, which began when Susan wrote down her wondrous visual experience and continued until Oliver's eyes closed.

However, in the winter of that year, when Oliver responded to Susan's first letter and their friendship blossomed, Oliver was diagnosed with ocular melanoma and began to lose his vision.

While one person opens his eyes to a new world he has never experienced before, the other person loses his familiar world.

Nevertheless, Oliver watched Susan's joy and delight and did not spare encouragement and support so that she could write a book.

Susan, heartbroken by the fact that she could do nothing to help Oliver, refused to be consumed by her grief and instead came up with an idea to comfort him.

Both men firmly believed in human neuroplasticity and the power of recovery, and they maintained their courage and humor until the very end.

"Dear Oliver" is a collection of letters between two neuroscientists who exchanged over 150 letters over a period of ten years, teaching each other to see the world differently. It is also a memoir written by one who is now left alone, remembering and missing the one who has passed away.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommendation

Part 1: The World We Met for the First Time

· A Question That Stings · Oliver Comes · Persistent, But Not Unusual · In the Bioluminescent Night Sea · Small Personal Victories · An Ominous Year-End · 2 Horatio Street, #3G · Stereo Number · A New Beginning · Morning Edition · Becoming an Author

Part 2: Sense and Friendship

· The Color of Words · Intermezzo I · Action, Perception, Cognition · Tungsten's Birthday · Side by Side, Illuminating Each Other · Outing · Intermezzo II · Compass Hat · Life is a Continuum of Tiresome Hardships · Creatures on the Sofa · Steel Nerves · The Return of 'Stereo Numbers' · Cesium and Barium's Birthdays · The Calculus of Friendship · Learning to Listen · Iridium's Birthday · Thoughts While Reading 'The Mind's Eye' · A Single Moment in Life · Companion Rocks

Part 3 Two Farewells

· Self-Experimentation · Interlude III · Bioelectricity · War and Peace · Therapeutic Brain Injury · Like a Father · Work and Love · Lead Birthday · A Final Farewell

Acknowledgements

Text and Image Copyright Information

Part 1: The World We Met for the First Time

· A Question That Stings · Oliver Comes · Persistent, But Not Unusual · In the Bioluminescent Night Sea · Small Personal Victories · An Ominous Year-End · 2 Horatio Street, #3G · Stereo Number · A New Beginning · Morning Edition · Becoming an Author

Part 2: Sense and Friendship

· The Color of Words · Intermezzo I · Action, Perception, Cognition · Tungsten's Birthday · Side by Side, Illuminating Each Other · Outing · Intermezzo II · Compass Hat · Life is a Continuum of Tiresome Hardships · Creatures on the Sofa · Steel Nerves · The Return of 'Stereo Numbers' · Cesium and Barium's Birthdays · The Calculus of Friendship · Learning to Listen · Iridium's Birthday · Thoughts While Reading 'The Mind's Eye' · A Single Moment in Life · Companion Rocks

Part 3 Two Farewells

· Self-Experimentation · Interlude III · Bioelectricity · War and Peace · Therapeutic Brain Injury · Like a Father · Work and Love · Lead Birthday · A Final Farewell

Acknowledgements

Text and Image Copyright Information

Detailed image

Into the book

We met on January 10, 1996.

It was the night before my husband, Dan Barry, was to leave on his first mission aboard the space shuttle.

(…) The doctor asked if I could imagine what the world would look like if I looked at it with both eyes.

I answered that I could imagine.

After all, I'm a professor of neurobiology at Mount Holyoke College.

I've read countless papers on visual processing, binocular vision, and stereopsis.

I thought that with the knowledge I had gained, I had a good understanding of what I was missing.

But that was a mistake.

--- p.16~17

I was surprised and impressed when I received the professor's letter on the 29th.

It's amazing how you welcomed the 'world' of this new (visual) space with such openness and wonder—even though you had a fear of heights in Kauai—and how you described that experience with such sensitivity, poetry, and precision.

(…) I think the professor’s experiences and stories should be presented in some form.

Because it may require a revision of the established doctrines of physiology and psychophysiology, and on a personal level, it may offer hope to those who have long ago more or less "accepted" their fate of living in a "flat" world forever.

I also hope that the profound fulfillment you felt as you experienced a kind of visual rebirth will serve to remind everyone that stereopsis (like all of our perceptual faculties) is a miracle and a privilege that we should not take for granted.

--- p.33~34

We essentially have two visual systems.

One is for perception, and one is for action.

These two visual systems appear to travel through different neural pathways in the brain.

In their book, The Vision of the Invisible, Goodale and Milner describe the case of a patient named Dee, who suffered damage to the perceptual pathway of one of the two neural pathways.

Dee cannot see the coffee cup with her eyes, nor can she recognize or name it as a coffee cup.

But there's nothing wrong with reaching out and picking up a coffee cup.

You can use your fingers to properly hold the handle of the glass.

So somewhere in your brain, you are recognizing the coffee cup.

--- p.172~173

Clive doesn't know that he knows Bach, but if you give him the sheet music and tell him the starting notes, he starts playing a Bach fugue.

He doesn't know what he knows.

His knowledge is not 'descriptive knowledge' or 'content knowledge'.

So you can't use that knowledge (for any purpose)... I think (digressing a bit) it was the same for John Hull, who couldn't see.

John Hull lost his sight for several years, and his visual imagery faded so much that he could neither think of the number 3 nor tell what it looked like—but he could instantly write '3' in the air.

How on earth could that be? --- p.175

I'm so glad to hear that you were so generous with your deaf student after meeting that dumb psychiatrist—there are definitely deaf psychiatrists and their patients who communicate perfectly well—and that the blind psychiatrist I mentioned in The Mind's Eye (Dennis Schulman, who is now a rabbi) said that his blindness made him even more sensitive to the subtle expressions of his patients.

--- p.182~183

My experience is mostly the opposite of what professors have these days.

I was trying to erase a stain from my suit when I discovered that it was on a mirror surface.

My reflection in the mirror is on the mirror surface—there is no sense that my image is in the mirror, 'beyond the mirror.'

(…) I used to have a severe fear of heights, so whenever I imagined myself falling from a high place, my body would automatically react, but now I am insensitive to heights to the point where it is dangerous.

(…) It seems like the professor has gained a new sense of space, and I have lost it.

--- p.201~202

When I first started seeing the 3rd dimension, I was so overwhelmed and ecstatic by this new sight that I worried I was going crazy.

It was a sad irony that the very person who immediately recognized how miraculous stereopsis was for me was the one who lost his own.

Two years later, while Oliver was writing his book, The Mind's Eye, which included five case studies, including his own and mine, he wrote to me:

“Now, the professor’s story and mine will be placed right next to each other.” --- p.203

Uncle Tungsten was Oliver's favorite nickname for his uncle.

Uncle Tungsten introduced Oliver to the world of chemistry, and Oliver titled his memoir of his childhood, Uncle Tungsten.

At the end, when I said Oliver was my Uncle Tungsten, I heard someone gasp, and after I finished my speech, I looked around to find Oliver.

Oliver was looking straight at me with his eyes wide open.

There are moments like that in life.

There are rare times when all the stars and planets in my universe seem to align.

That day was another such moment.

--- p.294

Oliver once wrote (borrowing Freud's words) that work and love were the two most important things in his life.

Writing was a big part of Oliver's work.

In the ten years I've known him, he has written four substantial books, despite a series of traumas.

When we first started exchanging letters, Oliver typed with two fingers on an IBM Selec- tric typewriter.

And when this became difficult, I wrote the letter by hand.

For several weeks in his later years, he dictated letters to others.

He never stopped working and writing.

--- p.369~370

Although he would pass away seven weeks later, Oliver was still contemplating what to write next, and he was intrigued by the different ways animals see the world.

He excitedly remarked that sea urchins have numerous light-sensitive cells in their tube feet.

And I wondered what it would be like to see the world as a sea urchin.

One time, he was observing an octopus, and he said that it felt like the octopus, a highly intelligent creature, was examining him with the same level of concentration as he was observing it.

--- p.372~373

When I received your first letter, excerpts from your journal in 2004, neither you nor I could have imagined that our first meeting would blossom into such a close friendship.

(…) Unfortunately, my condition has deteriorated rapidly over the past month.

My body has become extremely weak and I have more than a liter of ascites every day, so I have to drain it every morning and evening.

However, there are no major inconveniences, and thanks to Kate and Billy's unspeakable and dedicated support, I am able to stay active and continue writing as much as I can.

However, I'm not sure if I'll ever be able to finish my several ongoing projects, including my essay on space life.

(…) This letter is not the last farewell, but it seems that day is getting closer.

I don't know if I can make it through this month.

The deep and inspiring friendship I have shared with you over the past decade has been an unexpected and wonderful gift to my life.

Thank you very much.

It was the night before my husband, Dan Barry, was to leave on his first mission aboard the space shuttle.

(…) The doctor asked if I could imagine what the world would look like if I looked at it with both eyes.

I answered that I could imagine.

After all, I'm a professor of neurobiology at Mount Holyoke College.

I've read countless papers on visual processing, binocular vision, and stereopsis.

I thought that with the knowledge I had gained, I had a good understanding of what I was missing.

But that was a mistake.

--- p.16~17

I was surprised and impressed when I received the professor's letter on the 29th.

It's amazing how you welcomed the 'world' of this new (visual) space with such openness and wonder—even though you had a fear of heights in Kauai—and how you described that experience with such sensitivity, poetry, and precision.

(…) I think the professor’s experiences and stories should be presented in some form.

Because it may require a revision of the established doctrines of physiology and psychophysiology, and on a personal level, it may offer hope to those who have long ago more or less "accepted" their fate of living in a "flat" world forever.

I also hope that the profound fulfillment you felt as you experienced a kind of visual rebirth will serve to remind everyone that stereopsis (like all of our perceptual faculties) is a miracle and a privilege that we should not take for granted.

--- p.33~34

We essentially have two visual systems.

One is for perception, and one is for action.

These two visual systems appear to travel through different neural pathways in the brain.

In their book, The Vision of the Invisible, Goodale and Milner describe the case of a patient named Dee, who suffered damage to the perceptual pathway of one of the two neural pathways.

Dee cannot see the coffee cup with her eyes, nor can she recognize or name it as a coffee cup.

But there's nothing wrong with reaching out and picking up a coffee cup.

You can use your fingers to properly hold the handle of the glass.

So somewhere in your brain, you are recognizing the coffee cup.

--- p.172~173

Clive doesn't know that he knows Bach, but if you give him the sheet music and tell him the starting notes, he starts playing a Bach fugue.

He doesn't know what he knows.

His knowledge is not 'descriptive knowledge' or 'content knowledge'.

So you can't use that knowledge (for any purpose)... I think (digressing a bit) it was the same for John Hull, who couldn't see.

John Hull lost his sight for several years, and his visual imagery faded so much that he could neither think of the number 3 nor tell what it looked like—but he could instantly write '3' in the air.

How on earth could that be? --- p.175

I'm so glad to hear that you were so generous with your deaf student after meeting that dumb psychiatrist—there are definitely deaf psychiatrists and their patients who communicate perfectly well—and that the blind psychiatrist I mentioned in The Mind's Eye (Dennis Schulman, who is now a rabbi) said that his blindness made him even more sensitive to the subtle expressions of his patients.

--- p.182~183

My experience is mostly the opposite of what professors have these days.

I was trying to erase a stain from my suit when I discovered that it was on a mirror surface.

My reflection in the mirror is on the mirror surface—there is no sense that my image is in the mirror, 'beyond the mirror.'

(…) I used to have a severe fear of heights, so whenever I imagined myself falling from a high place, my body would automatically react, but now I am insensitive to heights to the point where it is dangerous.

(…) It seems like the professor has gained a new sense of space, and I have lost it.

--- p.201~202

When I first started seeing the 3rd dimension, I was so overwhelmed and ecstatic by this new sight that I worried I was going crazy.

It was a sad irony that the very person who immediately recognized how miraculous stereopsis was for me was the one who lost his own.

Two years later, while Oliver was writing his book, The Mind's Eye, which included five case studies, including his own and mine, he wrote to me:

“Now, the professor’s story and mine will be placed right next to each other.” --- p.203

Uncle Tungsten was Oliver's favorite nickname for his uncle.

Uncle Tungsten introduced Oliver to the world of chemistry, and Oliver titled his memoir of his childhood, Uncle Tungsten.

At the end, when I said Oliver was my Uncle Tungsten, I heard someone gasp, and after I finished my speech, I looked around to find Oliver.

Oliver was looking straight at me with his eyes wide open.

There are moments like that in life.

There are rare times when all the stars and planets in my universe seem to align.

That day was another such moment.

--- p.294

Oliver once wrote (borrowing Freud's words) that work and love were the two most important things in his life.

Writing was a big part of Oliver's work.

In the ten years I've known him, he has written four substantial books, despite a series of traumas.

When we first started exchanging letters, Oliver typed with two fingers on an IBM Selec- tric typewriter.

And when this became difficult, I wrote the letter by hand.

For several weeks in his later years, he dictated letters to others.

He never stopped working and writing.

--- p.369~370

Although he would pass away seven weeks later, Oliver was still contemplating what to write next, and he was intrigued by the different ways animals see the world.

He excitedly remarked that sea urchins have numerous light-sensitive cells in their tube feet.

And I wondered what it would be like to see the world as a sea urchin.

One time, he was observing an octopus, and he said that it felt like the octopus, a highly intelligent creature, was examining him with the same level of concentration as he was observing it.

--- p.372~373

When I received your first letter, excerpts from your journal in 2004, neither you nor I could have imagined that our first meeting would blossom into such a close friendship.

(…) Unfortunately, my condition has deteriorated rapidly over the past month.

My body has become extremely weak and I have more than a liter of ascites every day, so I have to drain it every morning and evening.

However, there are no major inconveniences, and thanks to Kate and Billy's unspeakable and dedicated support, I am able to stay active and continue writing as much as I can.

However, I'm not sure if I'll ever be able to finish my several ongoing projects, including my essay on space life.

(…) This letter is not the last farewell, but it seems that day is getting closer.

I don't know if I can make it through this month.

The deep and inspiring friendship I have shared with you over the past decade has been an unexpected and wonderful gift to my life.

Thank you very much.

--- p.381~382

Publisher's Review

It started with a letter that almost wasn't sent.

The friendship and intellectual adventures of two neuroscientists, Oliver Sacks and Susan Barry.

★ 10th Anniversary of Oliver Sacks's Passing, Includes Unpublished Handwritten Letters

★ Recommended by Dr. Namgung In, writer, and novelist Son Bo-mi

“A must-read for anyone who loves Sax’s books.

“I ended up shedding tears at the last chapter.”

- Temple Grandin (professor, zoologist, Colorado State University)

Oliver Sacks, a physician and neurologist who generously poured his genius into helping the vulnerable beings the world considered insignificant, and the world-beloved "poet of medicine,"

The last letter he left behind has arrived before us now, ten years after his death.

The recipient of the letter is neurobiologist Susan Barry, who lived with stereopsis and astigmatism for half her life before finally seeing the world in stereo at the age of forty-eight.

Susan was captivated every day by the beauty of the new three-dimensional world that unfolded before her eyes.

However, it was difficult for others to understand the experience, and it was a medical consensus that stereopsis could never develop after a certain period in infancy.

So Susan decided to keep this miraculous story a secret to herself.

Then one day, suddenly, with the hope that Oliver Sacks, a doctor who not only sympathized with but also empathized with his patients, might listen to his story as he did to his own patients, I wrote him a letter after much hesitation.

No one could have predicted that this one letter, which they had not expected much of a response to, would lead to a friendship that would last until Oliver's death, and that in the process, Susan would write a book about her story and become a writer who would help other poets and people with stereopsis.

Dear Oliver is a collection of letters between two neuroscientists who exchanged over 150 letters over a period of ten years, teaching each other to see the world differently. It is also a memoir written by one who is now alone, remembering and missing the one who has passed away.

Susan, who has gained stereoscopic vision for the first time in her life, and Oliver, who is losing his eyesight due to cancer.

The sad irony of the moment when two people's lives intersect

“If you want to know another person, you have to talk to him (…) If you don’t talk, the door to another world will never open.

Oliver Sacks was a master of this simple yet difficult act.”

―Son Bo-mi (novelist)

Oliver, a stereoscopic nerd who has always found stereopsis, which most people take for granted, a source of joy and wonder, was so excited to receive Susan's letter that he said he would come see her right away.

Based on that successful meeting and subsequent exchanges, “Stereo Sue” is Susan’s story written and published by Oliver.

Susan felt like a "monster" because she was different from others since childhood, and even after she gained stereopsis, she was afraid that people would not believe her and think she was crazy.

However, the enthusiastic response to this article gave him the confidence to finally write his own story in a book.

That book is “The Miracle of 3D,” which Nobel Prize winner in Physiology or Medicine Eric Kandel praised as “a book that is both poetry and science, and a magical book that gives us all hope.”

Meeting Oliver and writing this book transformed Susan from a patient to a subject and then to a writer.

Moreover, the relationship between two people who started out as a writer and his/her subject or a researcher and his/her research subject gradually develops into a special friendship.

But that winter, the year that Oliver responded to Susan's first letter and their relationship began, Oliver was diagnosed with ocular melanoma and began to lose his vision.

While one person opens his eyes to a new world he has never experienced before, the other person loses his familiar world.

As the vision in his right eye deteriorated, the stereoscopic vision that had delighted Oliver all his life also disappeared.

He stood in front of the mirror, trying to wipe a stain from his suit, when he realized that the stain was on the mirror surface.

Everything seemed flat and placed on the same two-dimensional plane, as if looking at a still life painting.

Now he lives in the 'hypocritical world' that Susan had once lived in, seen through her monocular vision.

Oliver, though feeling sorry for this situation, observed and recorded it meticulously with the curiosity of a doctor and writer.

As a result, the stories of two people who acquired a sense that neither of them had were included together in Oliver's book, The Mind's Eye.

Loss of sight was not the only misfortune that befell Oliver in his later years.

After undergoing back-to-back knee and spinal surgeries, he suffered from severe neuralgia that made it difficult for him to even move.

But even during that time, he never stopped reading and writing, and he never forgot to encourage and support Susan as she continued to write books.

Susan, heartbroken by the fact that she could do nothing to help Oliver, refused to be consumed by her grief and instead came up with an idea to comfort him.

Both men firmly believed in human neuroplasticity and the power of recovery, and they maintained their courage and humor until the very end.

“Last month, I discovered that my ocular melanoma had metastasized to my liver.

Metastatic cancer is not easily treatable, but some treatments can slow the progression.

“If those extra months are a good time, if I can write, meet friends, travel, and enjoy life during that time, then that’s enough for me.” (p. 360, Oliver Sacks)

“After your article was published in the New York Times, I received a sweet email from my brother.

“You may be losing someone who was like a father to you, but you still have a decent older brother you can rely on.’ Like a father, the doctor gave me my name, helped me forge a new identity, and sent me advice, encouragement, inspiration, and love.” (p. 363, Susan Barry)

True friends give each other the world

A person who teaches you how to see things differently

Oliver and Susan had so much in common that their 20-year age difference was insignificant.

He loves swimming and music, enjoys observing plants and animals, is usually shy, but delves into topics that interest him with a tenacious passion, and expresses his thoughts more clearly in writing than in speaking.

For them, letters were not only a means of communication, but also an essential element of writing that developed ideas and inspiration.

Above all, they looked at things we take for granted and pass by without a second thought with interest and affection.

Their conversation naturally spans a wide range of topics, from science and medicine to hobbies and personal lives, but at its core lies the diversity of senses, perception, and cognition.

Their vision extends to people who experience and understand the world in different ways, such as Dr. P, who could put a glove on his hand even though he could not see it with his eyes, a musician who could play a Bach fugue even though he had amnesia and forgot that he knew Bach, and an evolutionary scientist who could not see but understood the geometric structure of mollusks through his sense of touch, as well as to the various intelligent life forms that exist on Earth.

By using both the language of scientists and the vivid language of life, we explore what it means to 'see' and 'hear', and the differences between knowing with the head, feeling with the body, and knowing with action, and realize that the things we take for granted are not at all, but rather wonderful gifts and blessings.

Watching these two elderly scholars sparkle with childlike wonder and delight at even the smallest things, we can see how conversations with good friends enrich our senses, emotions, and thoughts.

As we follow the friendly letters of Dr. Sachs, who continues his intellectual voyage without losing his affection even during his illness, and Su, who sends comfort without sinking into sorrow (Dr. Namgung In, author), readers will find themselves absorbed in their curiosity, passion, and open attitude toward life.

The friendship and intellectual adventures of two neuroscientists, Oliver Sacks and Susan Barry.

★ 10th Anniversary of Oliver Sacks's Passing, Includes Unpublished Handwritten Letters

★ Recommended by Dr. Namgung In, writer, and novelist Son Bo-mi

“A must-read for anyone who loves Sax’s books.

“I ended up shedding tears at the last chapter.”

- Temple Grandin (professor, zoologist, Colorado State University)

Oliver Sacks, a physician and neurologist who generously poured his genius into helping the vulnerable beings the world considered insignificant, and the world-beloved "poet of medicine,"

The last letter he left behind has arrived before us now, ten years after his death.

The recipient of the letter is neurobiologist Susan Barry, who lived with stereopsis and astigmatism for half her life before finally seeing the world in stereo at the age of forty-eight.

Susan was captivated every day by the beauty of the new three-dimensional world that unfolded before her eyes.

However, it was difficult for others to understand the experience, and it was a medical consensus that stereopsis could never develop after a certain period in infancy.

So Susan decided to keep this miraculous story a secret to herself.

Then one day, suddenly, with the hope that Oliver Sacks, a doctor who not only sympathized with but also empathized with his patients, might listen to his story as he did to his own patients, I wrote him a letter after much hesitation.

No one could have predicted that this one letter, which they had not expected much of a response to, would lead to a friendship that would last until Oliver's death, and that in the process, Susan would write a book about her story and become a writer who would help other poets and people with stereopsis.

Dear Oliver is a collection of letters between two neuroscientists who exchanged over 150 letters over a period of ten years, teaching each other to see the world differently. It is also a memoir written by one who is now alone, remembering and missing the one who has passed away.

Susan, who has gained stereoscopic vision for the first time in her life, and Oliver, who is losing his eyesight due to cancer.

The sad irony of the moment when two people's lives intersect

“If you want to know another person, you have to talk to him (…) If you don’t talk, the door to another world will never open.

Oliver Sacks was a master of this simple yet difficult act.”

―Son Bo-mi (novelist)

Oliver, a stereoscopic nerd who has always found stereopsis, which most people take for granted, a source of joy and wonder, was so excited to receive Susan's letter that he said he would come see her right away.

Based on that successful meeting and subsequent exchanges, “Stereo Sue” is Susan’s story written and published by Oliver.

Susan felt like a "monster" because she was different from others since childhood, and even after she gained stereopsis, she was afraid that people would not believe her and think she was crazy.

However, the enthusiastic response to this article gave him the confidence to finally write his own story in a book.

That book is “The Miracle of 3D,” which Nobel Prize winner in Physiology or Medicine Eric Kandel praised as “a book that is both poetry and science, and a magical book that gives us all hope.”

Meeting Oliver and writing this book transformed Susan from a patient to a subject and then to a writer.

Moreover, the relationship between two people who started out as a writer and his/her subject or a researcher and his/her research subject gradually develops into a special friendship.

But that winter, the year that Oliver responded to Susan's first letter and their relationship began, Oliver was diagnosed with ocular melanoma and began to lose his vision.

While one person opens his eyes to a new world he has never experienced before, the other person loses his familiar world.

As the vision in his right eye deteriorated, the stereoscopic vision that had delighted Oliver all his life also disappeared.

He stood in front of the mirror, trying to wipe a stain from his suit, when he realized that the stain was on the mirror surface.

Everything seemed flat and placed on the same two-dimensional plane, as if looking at a still life painting.

Now he lives in the 'hypocritical world' that Susan had once lived in, seen through her monocular vision.

Oliver, though feeling sorry for this situation, observed and recorded it meticulously with the curiosity of a doctor and writer.

As a result, the stories of two people who acquired a sense that neither of them had were included together in Oliver's book, The Mind's Eye.

Loss of sight was not the only misfortune that befell Oliver in his later years.

After undergoing back-to-back knee and spinal surgeries, he suffered from severe neuralgia that made it difficult for him to even move.

But even during that time, he never stopped reading and writing, and he never forgot to encourage and support Susan as she continued to write books.

Susan, heartbroken by the fact that she could do nothing to help Oliver, refused to be consumed by her grief and instead came up with an idea to comfort him.

Both men firmly believed in human neuroplasticity and the power of recovery, and they maintained their courage and humor until the very end.

“Last month, I discovered that my ocular melanoma had metastasized to my liver.

Metastatic cancer is not easily treatable, but some treatments can slow the progression.

“If those extra months are a good time, if I can write, meet friends, travel, and enjoy life during that time, then that’s enough for me.” (p. 360, Oliver Sacks)

“After your article was published in the New York Times, I received a sweet email from my brother.

“You may be losing someone who was like a father to you, but you still have a decent older brother you can rely on.’ Like a father, the doctor gave me my name, helped me forge a new identity, and sent me advice, encouragement, inspiration, and love.” (p. 363, Susan Barry)

True friends give each other the world

A person who teaches you how to see things differently

Oliver and Susan had so much in common that their 20-year age difference was insignificant.

He loves swimming and music, enjoys observing plants and animals, is usually shy, but delves into topics that interest him with a tenacious passion, and expresses his thoughts more clearly in writing than in speaking.

For them, letters were not only a means of communication, but also an essential element of writing that developed ideas and inspiration.

Above all, they looked at things we take for granted and pass by without a second thought with interest and affection.

Their conversation naturally spans a wide range of topics, from science and medicine to hobbies and personal lives, but at its core lies the diversity of senses, perception, and cognition.

Their vision extends to people who experience and understand the world in different ways, such as Dr. P, who could put a glove on his hand even though he could not see it with his eyes, a musician who could play a Bach fugue even though he had amnesia and forgot that he knew Bach, and an evolutionary scientist who could not see but understood the geometric structure of mollusks through his sense of touch, as well as to the various intelligent life forms that exist on Earth.

By using both the language of scientists and the vivid language of life, we explore what it means to 'see' and 'hear', and the differences between knowing with the head, feeling with the body, and knowing with action, and realize that the things we take for granted are not at all, but rather wonderful gifts and blessings.

Watching these two elderly scholars sparkle with childlike wonder and delight at even the smallest things, we can see how conversations with good friends enrich our senses, emotions, and thoughts.

As we follow the friendly letters of Dr. Sachs, who continues his intellectual voyage without losing his affection even during his illness, and Su, who sends comfort without sinking into sorrow (Dr. Namgung In, author), readers will find themselves absorbed in their curiosity, passion, and open attitude toward life.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: August 30, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 388 pages | 498g | 140*210*20mm

- ISBN13: 9791193528808

- ISBN10: 1193528801

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)