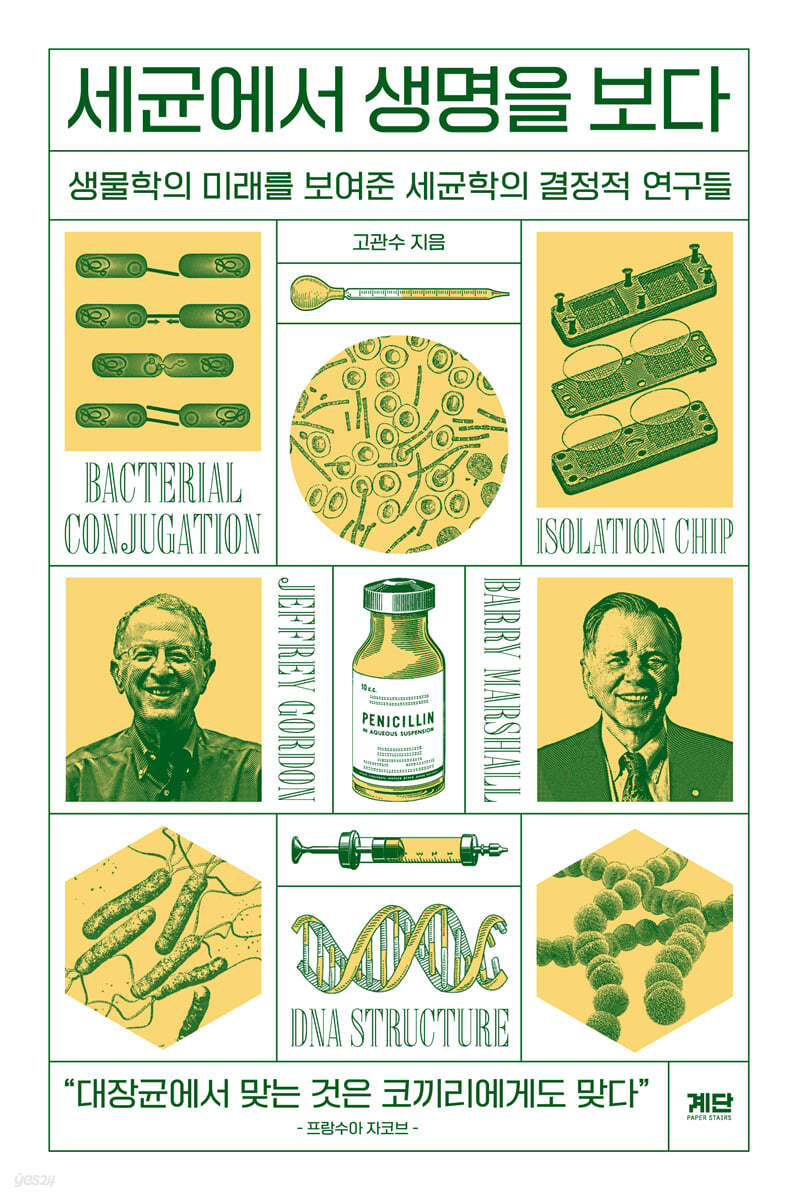

Seeing life in bacteria

|

Description

Book Introduction

"What works for E. coli works for elephants" - François Jacob

There is a moment when the before and after are completely different.

A decisive moment from which there is no return.

After looking at the bacteria under the microscope,

A world without germs, a biology without germs, could no longer exist.

The discovery of invisible creatures changed many things.

Nature opened up a new world for me as I began to see creatures that were too small to see.

It tells us what causes disease and shows us how to prevent and treat it.

It also gave hints as to where life originated and why parents and children resemble each other.

This vast body of biological knowledge and applications has been the result of the diverse efforts of many scientists who studied bacteria.

In this book, this is divided into several keywords.

A collection of the crucial research that has shaped everything in microbiology, particularly bacteriology.

Jacques Monod's statement, "What works for E. coli also works for elephants," clearly shows that microbiological research is not limited to studying small bacteria, but is at the forefront of uncovering the secrets of all life on earth.

It has been less than 200 years since Pasteur discovered that life must come from life, but now humans are repeatedly trying to create artificial life using the power of computers.

The mysteries of evolution, previously impossible to experiment with due to time constraints, are now being revealed, albeit in a limited way, through the short life cycle of E. coli. Molecular biology, which discovered vast uncharted continents by discovering genetic material, including DNA, is now relentlessly opening up new realms of knowledge and industry, developing exciting tools like PCR, restriction enzymes, and gene scissors.

The principles of life discovered in bacteria are now preparing to advance into new areas.

For us, who stand on that very border, this book shows us the past, where we stand now, and where the unknown world ahead stretches.

There is a moment when the before and after are completely different.

A decisive moment from which there is no return.

After looking at the bacteria under the microscope,

A world without germs, a biology without germs, could no longer exist.

The discovery of invisible creatures changed many things.

Nature opened up a new world for me as I began to see creatures that were too small to see.

It tells us what causes disease and shows us how to prevent and treat it.

It also gave hints as to where life originated and why parents and children resemble each other.

This vast body of biological knowledge and applications has been the result of the diverse efforts of many scientists who studied bacteria.

In this book, this is divided into several keywords.

A collection of the crucial research that has shaped everything in microbiology, particularly bacteriology.

Jacques Monod's statement, "What works for E. coli also works for elephants," clearly shows that microbiological research is not limited to studying small bacteria, but is at the forefront of uncovering the secrets of all life on earth.

It has been less than 200 years since Pasteur discovered that life must come from life, but now humans are repeatedly trying to create artificial life using the power of computers.

The mysteries of evolution, previously impossible to experiment with due to time constraints, are now being revealed, albeit in a limited way, through the short life cycle of E. coli. Molecular biology, which discovered vast uncharted continents by discovering genetic material, including DNA, is now relentlessly opening up new realms of knowledge and industry, developing exciting tools like PCR, restriction enzymes, and gene scissors.

The principles of life discovered in bacteria are now preparing to advance into new areas.

For us, who stand on that very border, this book shows us the past, where we stand now, and where the unknown world ahead stretches.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Entering

From a Dutch lumberyard | Crucial studies on bacteria

Part 1 LIFE

Chapter 1: All Living Things Have Parents - Louis Pasteur's Theory of Biogenesis

Where do living things come from? | Spontaneous generation and biogenesis | Swan-neck flask experiment | Although it is an experiment tailored to the desired result

Chapter 2: Humanity, Overlooking the Position of God - Craig Venter's Synthesis of Artificial Life

"Do it quickly.

"Discovery doesn't wait" | Creating artificial life | I want to create creatures with abilities that don't exist in nature.

Part 2 Disease DISEASE

Chapter 3.

Germs are the cause of disease - Robert Koch's first discovery of pathogens

Anthrax: Blackened Skin | Proving That Bacteria Cause Anthrax

Chapter 4.

This disease is also caused by bacteria - Barry Marshall's discovery of Helicobacter pylori

The Bacteria Seen but Undiscovered | The Beginning of Discovery | A Rejected Paper | Proving Yourself as a Guinea Pig | After the Discovery of Helicobacter pylori

Part 3 Treatment THERAPY

Chapter 5.

Humanity Armed with a Weapon Against Infectious Diseases - Alexander Fleming's Discovery of Penicillin

See dead bacteria surrounding mold | The penicillin paper doesn't mention what kind of mold it is | What was Fleming trying to do with penicillin? | The myth of blue mold and the birth of penicillin | No matter what anyone says, a great discovery that saved countless lives

Chapter 6.

Finding New Antibiotics and Viruses that Kill Bacteria - Kim Lewis's Teixobactin and Frederick Twort's Phage Therapy

How was the new antibiotic, teixobactin, discovered?

Bacteriophage, a virus that kills bacteria

_ Discovering Bacteriophages | _ Controversy Surrounding the First Discoverer of Phages | _ Phage Therapy: Non-Toxic and Side Effect-Free

Part 4 Classification

Chapter 7.

Identifying Bacteria - Hans Christian Gram's Bacterial Staining

Gram staining is the basis for bacterial observation and the standard for classification. Staining varies depending on the thickness of the cell wall. Beyond a simple observation tool, it also encompasses evolutionary classification of organisms. The principles and limitations of the Gram staining method are essential information for observing and classifying bacteria, as well as for prescribing antibiotics.

Chapter 8.

Bacteria Are Not Just One Kind - Carl Woods' Discovery of Archaea

"Research with little practical value" | Let's classify organisms by comparing base sequences | Ribosomal RNA is a molecular clock that measures evolutionary time | Awarding an 'Honorary Nobel Prize'

Part 5: Molecular Biology

Chapter 9. DNA is the Genetic Material - Oswald Avery's Transformation Experiments

Griffith's pneumococcus experiment | A substance that causes "predictable and genetic" changes | A research that wasn't fully accepted | Hershey and Chase's phage experiment puts an end to it

Chapter 10.

How Genes Work - The Discovery of Operons by François Jacob and Jacques Monod

François Jacob, a Nazi resistance fighter | "Chance and Necessity" by Jacques Monod | Unraveling the mechanisms of gene regulation | "Science by Day" and "Science by Night"

Part 6 Evolution

Chapter 11.

Bacteria Have Sexes: Joshua Lederberg's Discovery of Conjugation in E. coli

How Bacteria Share Genetic Information | "Sexual Activity Occurs in E. coli" | Nobel Prize Awarded at 22 | Esther Lederberg's Scientific Achievements Faded Next to Her Husband | The Medical and Evolutionary Significance of Horizontal Gene Transfer

Chapter 12.

Evolution in the Lab: Richard Lenski's Long-Term Evolution Experiment with E. coli

The Beginning of a Long-Term Evolution Experiment | What Happened to E. coli? | People Change, But Research Continues

Part 7.

BIOENGINEERING

Chapter 13.

PCR, a now-familiar technology - Kerry Mullis's development of PCR and Thomas Brock's discovery of thermophilic bacteria

PCR amplifies DNA molecules | An idea that came to me while driving with my girlfriend | The discovery of thermophilic bacteria made PCR an essential laboratory tool | The misuse of the Nobel Prize's authority

Chapter 14.

Bacterial immune tools transformed into cutting-edge biotechnology - Hamilton Smith's restriction enzymes and Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna's CRISPR

What do restriction enzymes "restrict"? | Restriction enzymes discovered in bacteria that don't infect viruses | CRISPR is the bacterial adaptive immune system | Discovery of the repetitive sequence called "CRISPR" | The genetic scissors "invented" by Doudna and Charpentier

Part 8.

COMMUNICATION

Chapter 15.

Bacteria Communicate - Woodland Hastings' Quorum Sensing

Why Bacteria Can Glow Simultaneously | How Bacteria Glow | Quorum Sensing Reveals Bacterial Sociality

Chapter 16.

Microbes Living Together - Jeffrey Gordon's Microbiome Research

The Interaction Between Microbes and Our Body's Metabolism | Is Gut Bacteria the Cause of My Fat? | Microbiome Research Expands Beyond the Gut to the Brain

Going out

Books and articles referenced

Acknowledgements

From a Dutch lumberyard | Crucial studies on bacteria

Part 1 LIFE

Chapter 1: All Living Things Have Parents - Louis Pasteur's Theory of Biogenesis

Where do living things come from? | Spontaneous generation and biogenesis | Swan-neck flask experiment | Although it is an experiment tailored to the desired result

Chapter 2: Humanity, Overlooking the Position of God - Craig Venter's Synthesis of Artificial Life

"Do it quickly.

"Discovery doesn't wait" | Creating artificial life | I want to create creatures with abilities that don't exist in nature.

Part 2 Disease DISEASE

Chapter 3.

Germs are the cause of disease - Robert Koch's first discovery of pathogens

Anthrax: Blackened Skin | Proving That Bacteria Cause Anthrax

Chapter 4.

This disease is also caused by bacteria - Barry Marshall's discovery of Helicobacter pylori

The Bacteria Seen but Undiscovered | The Beginning of Discovery | A Rejected Paper | Proving Yourself as a Guinea Pig | After the Discovery of Helicobacter pylori

Part 3 Treatment THERAPY

Chapter 5.

Humanity Armed with a Weapon Against Infectious Diseases - Alexander Fleming's Discovery of Penicillin

See dead bacteria surrounding mold | The penicillin paper doesn't mention what kind of mold it is | What was Fleming trying to do with penicillin? | The myth of blue mold and the birth of penicillin | No matter what anyone says, a great discovery that saved countless lives

Chapter 6.

Finding New Antibiotics and Viruses that Kill Bacteria - Kim Lewis's Teixobactin and Frederick Twort's Phage Therapy

How was the new antibiotic, teixobactin, discovered?

Bacteriophage, a virus that kills bacteria

_ Discovering Bacteriophages | _ Controversy Surrounding the First Discoverer of Phages | _ Phage Therapy: Non-Toxic and Side Effect-Free

Part 4 Classification

Chapter 7.

Identifying Bacteria - Hans Christian Gram's Bacterial Staining

Gram staining is the basis for bacterial observation and the standard for classification. Staining varies depending on the thickness of the cell wall. Beyond a simple observation tool, it also encompasses evolutionary classification of organisms. The principles and limitations of the Gram staining method are essential information for observing and classifying bacteria, as well as for prescribing antibiotics.

Chapter 8.

Bacteria Are Not Just One Kind - Carl Woods' Discovery of Archaea

"Research with little practical value" | Let's classify organisms by comparing base sequences | Ribosomal RNA is a molecular clock that measures evolutionary time | Awarding an 'Honorary Nobel Prize'

Part 5: Molecular Biology

Chapter 9. DNA is the Genetic Material - Oswald Avery's Transformation Experiments

Griffith's pneumococcus experiment | A substance that causes "predictable and genetic" changes | A research that wasn't fully accepted | Hershey and Chase's phage experiment puts an end to it

Chapter 10.

How Genes Work - The Discovery of Operons by François Jacob and Jacques Monod

François Jacob, a Nazi resistance fighter | "Chance and Necessity" by Jacques Monod | Unraveling the mechanisms of gene regulation | "Science by Day" and "Science by Night"

Part 6 Evolution

Chapter 11.

Bacteria Have Sexes: Joshua Lederberg's Discovery of Conjugation in E. coli

How Bacteria Share Genetic Information | "Sexual Activity Occurs in E. coli" | Nobel Prize Awarded at 22 | Esther Lederberg's Scientific Achievements Faded Next to Her Husband | The Medical and Evolutionary Significance of Horizontal Gene Transfer

Chapter 12.

Evolution in the Lab: Richard Lenski's Long-Term Evolution Experiment with E. coli

The Beginning of a Long-Term Evolution Experiment | What Happened to E. coli? | People Change, But Research Continues

Part 7.

BIOENGINEERING

Chapter 13.

PCR, a now-familiar technology - Kerry Mullis's development of PCR and Thomas Brock's discovery of thermophilic bacteria

PCR amplifies DNA molecules | An idea that came to me while driving with my girlfriend | The discovery of thermophilic bacteria made PCR an essential laboratory tool | The misuse of the Nobel Prize's authority

Chapter 14.

Bacterial immune tools transformed into cutting-edge biotechnology - Hamilton Smith's restriction enzymes and Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna's CRISPR

What do restriction enzymes "restrict"? | Restriction enzymes discovered in bacteria that don't infect viruses | CRISPR is the bacterial adaptive immune system | Discovery of the repetitive sequence called "CRISPR" | The genetic scissors "invented" by Doudna and Charpentier

Part 8.

COMMUNICATION

Chapter 15.

Bacteria Communicate - Woodland Hastings' Quorum Sensing

Why Bacteria Can Glow Simultaneously | How Bacteria Glow | Quorum Sensing Reveals Bacterial Sociality

Chapter 16.

Microbes Living Together - Jeffrey Gordon's Microbiome Research

The Interaction Between Microbes and Our Body's Metabolism | Is Gut Bacteria the Cause of My Fat? | Microbiome Research Expands Beyond the Gut to the Brain

Going out

Books and articles referenced

Acknowledgements

Detailed image

Into the book

The invention of the petri dish, the creation of solid media from agar, and the development of infection tools such as twigs were all done by Koch and his disciples.

So to speak, they pioneered a new field by designing and creating the basic tools of modern bacteriology.

Koch pondered for quite some time how to cultivate pure bacteria.

Then I figured out that nothing from outside could enter a liquid droplet that didn't come into contact with anything else.

Koch took inspiration from this and created a simple incubation device.

--- p.63

He had submitted an abstract to a conference (the Australian Society of Gastroenterology) to present on bacteria found in the stomach, but he kept the rejection letter from the conference organisers.

It was a polite but cold rejection letter stating that only 56 of the 67 submitted abstracts were accepted for publication.

Among the 11 abstracts rejected for publication, one was the one that would win the Nobel Prize 20 years later!

--- p.75~76

Marshall's discovery of Helicobacter pylori is considered to be more than just the discovery of a single pathogen causing a disease.

Why is that? In the 1980s, most of the pathogens causing major infectious diseases were already known.

In this context, Marshall's discovery was a symbolic event that showed that diseases that had not been considered infectious were caused by bacteria.

If bacteria cause peptic ulcers, what about multiple sclerosis or rheumatoid arthritis? Or even Alzheimer's? Couldn't that also be a type of infectious disease? Now, the perspective and scope of how we view bacteria and microorganisms have shifted.

--- p.85

It is certain that after the publication of his paper, Fleming also spent some time considering whether penicillin could be used as a treatment.

(……) Perhaps the biggest reason for the waning interest was that penicillin was a substance that was very difficult to isolate.

As Fleming wrote in his paper, penicillin was not easily separated because it did not dissolve in ether or chloroform, and it was not easy to concentrate. In addition, it was very unstable and easily disappeared even if left alone.

So, I thought it would be difficult to have any clinical expectations.

What may be strange, or even regrettable, is that Fleming attempted to solve the problem of separation and concentration solely by himself or his team of biologists.

This is even more evident when we consider that Howard Florey of Oxford University later solved this problem and developed a cure through experts from various fields including microbiology and chemistry, including Ernst Chain and Norman Heatley.

--- p.99

There is one scientific question about Fleming's discovery.

The point is that no one has been able to replicate the exact situation in which Fleming discovered penicillin.

It is said that even Fleming could not reproduce it.

That is, when the mold in the paper was grown in the same location as in the photo while staphylococci were growing in a culture dish, the same phenomenon as in the photo presented in Fleming's paper did not appear.

Of course, Fleming's photo was not manipulated.

So how did this happen?

--- p.102

(Bacterial) phages have great specificity for bacteria.

Phages do not attack all bacteria.

Because it targets only specific bacteria, it can treat infections without destroying the microbial community within the human body.

Additionally, since the phage ceases to function when the host bacteria dies, there are no side effects beyond the desired effect.

Its advantages include that it is non-toxic to animals, plants, and the environment, and that it rapidly multiplies even with a small amount of treatment. Furthermore, because the place where phages multiply is the place where infection occurred, the effect appears quickly.

Another advantage is that it is effective for patients who are allergic to antibiotics and works against bacteria that form biofilms, which are difficult to treat.

It is also worth noting that it is simple and inexpensive to produce.

--- p.124

Bacteriologists call bacteria that are purple "gram-positive bacteria" and bacteria that stain red "gram-negative bacteria."

As the arbitrary classification of bacteria into Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria based on staining results was found to have a structural basis, the two taxa were considered to be naturally classified, that is, evolutionarily differentiated taxa.

--- p.131~132

The Gram staining method was rediscovered in the mid-20th century.

In particular, in 1974, Pierce Gardner, then a professor at Harvard Medical School, argued that Gram staining should be included in the medical examination of patients with acute bacterial infections and that the results should be provided to primary care physicians.

It was emphasized that Gram staining is basic medical information for determining whether a patient has a bacterial infection and the type of bacteria.

In particular, whether the infecting bacteria are gram-positive or gram-negative is crucial in selecting first-line antibiotics to treat infectious diseases.

--- p.140

Science cites the assessment of University of Washington biochemistry professor Alan Weiner: “Almost every biologist and physician should give Woods an honorary Nobel Prize.”

--- p.156

Until the early 1940s, scientists believed that because bacteria reproduced through binary fission, all bacteria from a single bacterium were genetically identical.

So I thought it would be difficult to do genetic research with bacteria.

Shouldn't there be some detectable change to study genetics? However, in the 1940s and 1950s, it was discovered that not only does bacteria transmit genetic information through division (called vertical gene transfer), but also horizontal gene transfer, a method by which genetic information is transmitted between organisms, exists.

The discovery of horizontal gene transfer simultaneously expanded the concepts and methodology of genetics and brought about a dramatic paradigm shift in evolutionary biology.

--- p.199~200

There are three mechanisms that cause horizontal gene transfer in bacteria.

(……) However, the two mechanisms other than transformation, namely conjugation and transduction, were both discovered primarily by one scientist.

This changed our fundamental understanding of bacteria, gave genetics and molecular biology powerful tools, and broadened our perspective on evolution.

That scientist is Joshua Lederberg.

He was a typical genius scientist who discovered these things in his 20s.

--- p.200~201

His discovery was the first to reveal how genes can be exchanged between bacteria, meaning that genes can be passed on and received between different organisms, resulting in offspring with new combinations of genes.

That is, it is known that bacteria, like animals and plants, have sex.

--- p.202

The acquisition and spread of antibiotic resistance through horizontal gene transfer is a clear example of evolution.

Since antibiotics themselves act as evolutionary pressure, bacteria with antibiotic resistance are selected, and the bacteria's effective response to that pressure is horizontal gene transfer.

The impact of horizontal gene transfer on evolution can be seen not only in antibiotic resistance but also in phylogenetics.

--- p.214

We learn about Lenski's long-term evolution experiment, which leading evolutionary biologists Richard Dawkins and Jerry Coyne praised for providing experimental evidence for evolution.

In this study, the moment the research began is important, but the perseverance to continue the research is also impressive.

--- p.219

Samples were taken from Yellowstone's hot springs starting in 1965.

Then I noticed that there was a place where pink bubbles were forming, and I confirmed that the pink substance coming out of the hot spring water that was over 82 degrees Celsius was mixed with protein.

What are you talking about? It means that there is life.

It is a living organism that can produce healthy proteins and maintain life even at very high temperatures.

Brock immediately got to work.

A study on bacteria living in Yellowstone's hot springs!

--- p.212

In fact, in the invention and development of PCR itself, bacteria may not have been the main characters, although the DNA polymerase first used by Mullis was purified from E. coli.

However, the discovery of a thermophilic bacterium called Thermus aquaticus and the purification of a heat-resistant DNA polymerase from it are brilliant moments in bacteriology, and are significant achievements in that they led to the great technology called PCR.

--- p.257

It deals with restriction enzymes and the CRISPR-Cas system.

These are commonly referred to as 'genetic scissors', and they are substances or technologies that immediately became essential tools in modern biology after their discovery.

(……) It is not well known that these originate from the bacterial immune system.

(……) Shouldn't bacteria also be prepared for things that come to harm and kill them? Among the defenses bacteria have prepared against viral invasion are restriction enzymes and something called the CRISPR-Cas system.

We are doing all sorts of strange(!) things by taking advantage of this defense system that bacteria have.

--- p.261~262

They figured out how the CRISPR-Cas system works, but they went one step further.

In fact, that one step was a huge step forward.

After looking through all the components of the CRISPR-Cas system, I thought there might be something more I could do with it.

That is, the idea was that the desired DNA could be cut depending on the base sequence of crRNA inserted.

It was the discovery of gene editing tools.

And in order to make it easier to use, Doudna's lab designed and created a "single-guide RNA"—an RNA molecule that carries the guide information of crRNA on one side and acts as a handle to bind to DNA, which is the characteristic of tracrRNA on the other.

So to speak, Doudna and Charpentier 'invented' a genetic reprogramming tool based on a natural, bacterial tool called the CRISPR-Cas system.

--- p.277

Quorum sensing does not only occur between bacteria of the same species.

It occurs between bacteria of different species, and even between organisms belonging to different kingdoms or even different domains.

(……) Living things exchange signals like this to maintain a group and increase their chances of survival.

So scientists began to think of quorum sensing as indicating the 'sociality' of bacteria, and began to refer to the field that studies the collective behavior of microorganisms, or social behavior, as 'sociomicrobiology.'

--- p.230

This result strongly indicates that the composition of intestinal bacteria is the 'cause' of obesity in mice.

It also meant that obesity traits could be transmitted between individuals through fecal microbiota transplantation.

It was a very meaningful result.

Does this mean that transplanting the microbiome of a lean person into a human could help obese people lose weight without having to endure the arduous process of dieting? This finding goes beyond mere observation, offering hope that it could address one of modern man's greatest concerns.

Here we see why Gordon's research is a landmark not only in scientific terms but also in its public impact.

--- p.305

Even if they eat the same food or food, if there are more Firmicutes bacteria, they can transfer more calories to the host, such as mice or humans.

Firmicutes, which would have been a very useful bacterium in an era when food was scarce, such as the Neolithic Age, has become a useless and highly efficient bacterium in modern, developed countries where food is abundant.

(……) All things being equal, after one year, these extra calories will translate into a weight gain of approximately 5 kilograms.

Just because of the differences in the bacteria in my body.

So to speak, they pioneered a new field by designing and creating the basic tools of modern bacteriology.

Koch pondered for quite some time how to cultivate pure bacteria.

Then I figured out that nothing from outside could enter a liquid droplet that didn't come into contact with anything else.

Koch took inspiration from this and created a simple incubation device.

--- p.63

He had submitted an abstract to a conference (the Australian Society of Gastroenterology) to present on bacteria found in the stomach, but he kept the rejection letter from the conference organisers.

It was a polite but cold rejection letter stating that only 56 of the 67 submitted abstracts were accepted for publication.

Among the 11 abstracts rejected for publication, one was the one that would win the Nobel Prize 20 years later!

--- p.75~76

Marshall's discovery of Helicobacter pylori is considered to be more than just the discovery of a single pathogen causing a disease.

Why is that? In the 1980s, most of the pathogens causing major infectious diseases were already known.

In this context, Marshall's discovery was a symbolic event that showed that diseases that had not been considered infectious were caused by bacteria.

If bacteria cause peptic ulcers, what about multiple sclerosis or rheumatoid arthritis? Or even Alzheimer's? Couldn't that also be a type of infectious disease? Now, the perspective and scope of how we view bacteria and microorganisms have shifted.

--- p.85

It is certain that after the publication of his paper, Fleming also spent some time considering whether penicillin could be used as a treatment.

(……) Perhaps the biggest reason for the waning interest was that penicillin was a substance that was very difficult to isolate.

As Fleming wrote in his paper, penicillin was not easily separated because it did not dissolve in ether or chloroform, and it was not easy to concentrate. In addition, it was very unstable and easily disappeared even if left alone.

So, I thought it would be difficult to have any clinical expectations.

What may be strange, or even regrettable, is that Fleming attempted to solve the problem of separation and concentration solely by himself or his team of biologists.

This is even more evident when we consider that Howard Florey of Oxford University later solved this problem and developed a cure through experts from various fields including microbiology and chemistry, including Ernst Chain and Norman Heatley.

--- p.99

There is one scientific question about Fleming's discovery.

The point is that no one has been able to replicate the exact situation in which Fleming discovered penicillin.

It is said that even Fleming could not reproduce it.

That is, when the mold in the paper was grown in the same location as in the photo while staphylococci were growing in a culture dish, the same phenomenon as in the photo presented in Fleming's paper did not appear.

Of course, Fleming's photo was not manipulated.

So how did this happen?

--- p.102

(Bacterial) phages have great specificity for bacteria.

Phages do not attack all bacteria.

Because it targets only specific bacteria, it can treat infections without destroying the microbial community within the human body.

Additionally, since the phage ceases to function when the host bacteria dies, there are no side effects beyond the desired effect.

Its advantages include that it is non-toxic to animals, plants, and the environment, and that it rapidly multiplies even with a small amount of treatment. Furthermore, because the place where phages multiply is the place where infection occurred, the effect appears quickly.

Another advantage is that it is effective for patients who are allergic to antibiotics and works against bacteria that form biofilms, which are difficult to treat.

It is also worth noting that it is simple and inexpensive to produce.

--- p.124

Bacteriologists call bacteria that are purple "gram-positive bacteria" and bacteria that stain red "gram-negative bacteria."

As the arbitrary classification of bacteria into Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria based on staining results was found to have a structural basis, the two taxa were considered to be naturally classified, that is, evolutionarily differentiated taxa.

--- p.131~132

The Gram staining method was rediscovered in the mid-20th century.

In particular, in 1974, Pierce Gardner, then a professor at Harvard Medical School, argued that Gram staining should be included in the medical examination of patients with acute bacterial infections and that the results should be provided to primary care physicians.

It was emphasized that Gram staining is basic medical information for determining whether a patient has a bacterial infection and the type of bacteria.

In particular, whether the infecting bacteria are gram-positive or gram-negative is crucial in selecting first-line antibiotics to treat infectious diseases.

--- p.140

Science cites the assessment of University of Washington biochemistry professor Alan Weiner: “Almost every biologist and physician should give Woods an honorary Nobel Prize.”

--- p.156

Until the early 1940s, scientists believed that because bacteria reproduced through binary fission, all bacteria from a single bacterium were genetically identical.

So I thought it would be difficult to do genetic research with bacteria.

Shouldn't there be some detectable change to study genetics? However, in the 1940s and 1950s, it was discovered that not only does bacteria transmit genetic information through division (called vertical gene transfer), but also horizontal gene transfer, a method by which genetic information is transmitted between organisms, exists.

The discovery of horizontal gene transfer simultaneously expanded the concepts and methodology of genetics and brought about a dramatic paradigm shift in evolutionary biology.

--- p.199~200

There are three mechanisms that cause horizontal gene transfer in bacteria.

(……) However, the two mechanisms other than transformation, namely conjugation and transduction, were both discovered primarily by one scientist.

This changed our fundamental understanding of bacteria, gave genetics and molecular biology powerful tools, and broadened our perspective on evolution.

That scientist is Joshua Lederberg.

He was a typical genius scientist who discovered these things in his 20s.

--- p.200~201

His discovery was the first to reveal how genes can be exchanged between bacteria, meaning that genes can be passed on and received between different organisms, resulting in offspring with new combinations of genes.

That is, it is known that bacteria, like animals and plants, have sex.

--- p.202

The acquisition and spread of antibiotic resistance through horizontal gene transfer is a clear example of evolution.

Since antibiotics themselves act as evolutionary pressure, bacteria with antibiotic resistance are selected, and the bacteria's effective response to that pressure is horizontal gene transfer.

The impact of horizontal gene transfer on evolution can be seen not only in antibiotic resistance but also in phylogenetics.

--- p.214

We learn about Lenski's long-term evolution experiment, which leading evolutionary biologists Richard Dawkins and Jerry Coyne praised for providing experimental evidence for evolution.

In this study, the moment the research began is important, but the perseverance to continue the research is also impressive.

--- p.219

Samples were taken from Yellowstone's hot springs starting in 1965.

Then I noticed that there was a place where pink bubbles were forming, and I confirmed that the pink substance coming out of the hot spring water that was over 82 degrees Celsius was mixed with protein.

What are you talking about? It means that there is life.

It is a living organism that can produce healthy proteins and maintain life even at very high temperatures.

Brock immediately got to work.

A study on bacteria living in Yellowstone's hot springs!

--- p.212

In fact, in the invention and development of PCR itself, bacteria may not have been the main characters, although the DNA polymerase first used by Mullis was purified from E. coli.

However, the discovery of a thermophilic bacterium called Thermus aquaticus and the purification of a heat-resistant DNA polymerase from it are brilliant moments in bacteriology, and are significant achievements in that they led to the great technology called PCR.

--- p.257

It deals with restriction enzymes and the CRISPR-Cas system.

These are commonly referred to as 'genetic scissors', and they are substances or technologies that immediately became essential tools in modern biology after their discovery.

(……) It is not well known that these originate from the bacterial immune system.

(……) Shouldn't bacteria also be prepared for things that come to harm and kill them? Among the defenses bacteria have prepared against viral invasion are restriction enzymes and something called the CRISPR-Cas system.

We are doing all sorts of strange(!) things by taking advantage of this defense system that bacteria have.

--- p.261~262

They figured out how the CRISPR-Cas system works, but they went one step further.

In fact, that one step was a huge step forward.

After looking through all the components of the CRISPR-Cas system, I thought there might be something more I could do with it.

That is, the idea was that the desired DNA could be cut depending on the base sequence of crRNA inserted.

It was the discovery of gene editing tools.

And in order to make it easier to use, Doudna's lab designed and created a "single-guide RNA"—an RNA molecule that carries the guide information of crRNA on one side and acts as a handle to bind to DNA, which is the characteristic of tracrRNA on the other.

So to speak, Doudna and Charpentier 'invented' a genetic reprogramming tool based on a natural, bacterial tool called the CRISPR-Cas system.

--- p.277

Quorum sensing does not only occur between bacteria of the same species.

It occurs between bacteria of different species, and even between organisms belonging to different kingdoms or even different domains.

(……) Living things exchange signals like this to maintain a group and increase their chances of survival.

So scientists began to think of quorum sensing as indicating the 'sociality' of bacteria, and began to refer to the field that studies the collective behavior of microorganisms, or social behavior, as 'sociomicrobiology.'

--- p.230

This result strongly indicates that the composition of intestinal bacteria is the 'cause' of obesity in mice.

It also meant that obesity traits could be transmitted between individuals through fecal microbiota transplantation.

It was a very meaningful result.

Does this mean that transplanting the microbiome of a lean person into a human could help obese people lose weight without having to endure the arduous process of dieting? This finding goes beyond mere observation, offering hope that it could address one of modern man's greatest concerns.

Here we see why Gordon's research is a landmark not only in scientific terms but also in its public impact.

--- p.305

Even if they eat the same food or food, if there are more Firmicutes bacteria, they can transfer more calories to the host, such as mice or humans.

Firmicutes, which would have been a very useful bacterium in an era when food was scarce, such as the Neolithic Age, has become a useless and highly efficient bacterium in modern, developed countries where food is abundant.

(……) All things being equal, after one year, these extra calories will translate into a weight gain of approximately 5 kilograms.

Just because of the differences in the bacteria in my body.

--- p.306~307

Publisher's Review

From the basic principles of life

From cutting-edge research that opens the future,

Everything You Need to Know About Bacteria Research: The Secrets of Life

It brings together the seminal research that shaped everything we know about microbiology, particularly bacteriology, today.

It is thanks to these individuals that the author is able to study antibiotic resistance, and the world that the young readers of this book will open will also begin on this very foundation.

We take a look back at past bacterial research that uncovered the causes and cures of disease, and pair it with cutting-edge research that has made biology the driving force of new industries, along with current scientists.

Through this book, you can look back on the 150-year history of bacteriology at a glance and gauge the future direction of development in biology.

"We introduce the most important studies on bacteriology or bacteria that have been conducted since Leeuwenhoek's discovery.

Although I chose these studies based on somewhat subjective criteria, I believe few would consider them unimportant.

We grouped scientists and their research under eight keywords.

We first selected groundbreaking studies from the past and paired them with corresponding recent studies, or grouped studies that were comparable to each other.

Although the overall flow of the research field is discussed, the focus is on the first, most important, or most impressive papers in the field.

Reading the original paper and understanding the field based on it made me think more deeply about the originality and impact of scholarship and research.

I was also able to see the resolution's contents being different from what was summarized and explained in the textbook.

I believe that the papers and articles mentioned here will be sufficient to understand the flow of bacterial research.”

When the microscope came out, bacteria were visible,

A world without germs is no longer imaginable.

The discovery is a crack.

It's a crack so big that you can't go back to how it was before.

After Gram discovered a way to stain bacteria, no biologist since then has used the previous staining method.

After Koch discovered that the cause of infectious diseases was a specific bacterium, no one looked for the cause of infectious diseases anywhere other than bacteria.

I crossed a river from which there is no return.

When Thomas Brock discovered bacteria that could survive at temperatures so high that water would boil, there were no longer any restrictions on the environment in which bacteria could live.

The scope of thought and the realm of possibility have expanded enormously.

The people we see in this book are the ones who created these cracks and broke these limitations.

When Kerry Mullis invented PCR, everyone used the tool after that.

People used to drive nails with their hands, but when hammers came out, no one drove nails with their hands.

In this way, we broke away from the past of 'miasma' and sought the cause of disease in bacteria (pathogens), and after elucidating the principle of quorum sensing, we opened the field of 'sociomicrobiology', which studies how bacteria communicate with each other.

This book is about this 'decisive moment' in bacteriology and biology.

The discovery of Helicobacter pylori

The reason I received the Nobel Prize

If you know what you want to know, the Internet is probably a better source of information than books.

If you're curious about Helicobacter pylori, just type the word "helicobacter" into the internet and you'll see a screen full of information about what it looks like, what its characteristics are, who discovered it, and what diseases it causes.

That would probably be faster and more accurate than searching for a book.

So what should we look for in a book? Helicobacter pylori lives in the human stomach, and the discovery of it warrants a Nobel Prize? Was this bacterium so difficult to find? Or is there another reason? These days, health screenings include Helicobacter pylori testing, but was that such a daunting task in the 1980s? The Nobel Prize is often awarded for groundbreaking research that revolutionizes a field. But is the discovery of Helicobacter pylori even that significant? What are the implications of this discovery, its place in the study of pathogens, and its significance? Isn't what we want from a book not just to present well-organized facts in an accessible manner, but also to understand the context, impact, ramifications, and connections of those facts? This is probably not easily conveyed in a brief, three-line summary.

Isn't this exactly what we want from a book? This book is permeated with the effort to bring out these unique qualities that only a book can offer.

Why are Korean scientists mentioned in popular science books?

I wonder if the research results will come out

If you read general science books, you will rarely encounter Korean scientists.

Perhaps it is because we do not yet have the resources to cover textbook-level verified stories in a general-level science book.

However, I also think that even if they are not famous scientists or engineers who deserve a chapter or subheading, if they are a scientist with some level of verification, they would be worthy of being included in a general-level science book.

I often see foreign research results cited as the basis for explanations, but there are probably quite a few Korean scientists in each field who have produced results at a similar level.

I heard that our universities and research institutes have many talented researchers, and that they have a considerable amount of space and budget for research and experiments.

But why aren't there any Korean scientists named? Newspaper articles and broadcasts show Korean researchers publishing numerous papers and often producing noteworthy results. But why do popular science books only feature names from the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Japan, and China? There are also quite a few Brazilians and Indians, so why aren't there any Koreans? Surely, there must have been quite a few noteworthy results among the papers published while studying or working as doctoral students abroad.

But why aren't these studies mentioned in popular science books written by domestic authors?

Why do Korean authors of general science books avoid including the names of their colleagues, seniors, or juniors? The reasons may be numerous, but one thing is clear: while scholars from many other countries appear, Koreans don't appear nearly as often.

However, this book contains several research results from active domestic scientists.

Nice and friendly.

Wouldn't it be better to cite and mention Korean authors' work, if at all possible? It might be possible to avoid mentioning anything, but when similar research results are attributed to Korean researchers, interest is immediately drawn, and any Korean reader will likely be even more intrigued.

This book introduces Professor Richard Lenski, who is well known for his long-term evolution experiments on E. coli, and describes the research that Professor Jihyun Kim of Yonsei University conducted with Professor Lenski.

Domestic scholars also appear in chapters on quorum sensing, antibiotic resistance, and microbiome research.

Now that the number of domestic researchers writing for the general public is increasing, I expect that the number of stories about their colleagues, seniors, and juniors will gradually increase.

From cutting-edge research that opens the future,

Everything You Need to Know About Bacteria Research: The Secrets of Life

It brings together the seminal research that shaped everything we know about microbiology, particularly bacteriology, today.

It is thanks to these individuals that the author is able to study antibiotic resistance, and the world that the young readers of this book will open will also begin on this very foundation.

We take a look back at past bacterial research that uncovered the causes and cures of disease, and pair it with cutting-edge research that has made biology the driving force of new industries, along with current scientists.

Through this book, you can look back on the 150-year history of bacteriology at a glance and gauge the future direction of development in biology.

"We introduce the most important studies on bacteriology or bacteria that have been conducted since Leeuwenhoek's discovery.

Although I chose these studies based on somewhat subjective criteria, I believe few would consider them unimportant.

We grouped scientists and their research under eight keywords.

We first selected groundbreaking studies from the past and paired them with corresponding recent studies, or grouped studies that were comparable to each other.

Although the overall flow of the research field is discussed, the focus is on the first, most important, or most impressive papers in the field.

Reading the original paper and understanding the field based on it made me think more deeply about the originality and impact of scholarship and research.

I was also able to see the resolution's contents being different from what was summarized and explained in the textbook.

I believe that the papers and articles mentioned here will be sufficient to understand the flow of bacterial research.”

When the microscope came out, bacteria were visible,

A world without germs is no longer imaginable.

The discovery is a crack.

It's a crack so big that you can't go back to how it was before.

After Gram discovered a way to stain bacteria, no biologist since then has used the previous staining method.

After Koch discovered that the cause of infectious diseases was a specific bacterium, no one looked for the cause of infectious diseases anywhere other than bacteria.

I crossed a river from which there is no return.

When Thomas Brock discovered bacteria that could survive at temperatures so high that water would boil, there were no longer any restrictions on the environment in which bacteria could live.

The scope of thought and the realm of possibility have expanded enormously.

The people we see in this book are the ones who created these cracks and broke these limitations.

When Kerry Mullis invented PCR, everyone used the tool after that.

People used to drive nails with their hands, but when hammers came out, no one drove nails with their hands.

In this way, we broke away from the past of 'miasma' and sought the cause of disease in bacteria (pathogens), and after elucidating the principle of quorum sensing, we opened the field of 'sociomicrobiology', which studies how bacteria communicate with each other.

This book is about this 'decisive moment' in bacteriology and biology.

The discovery of Helicobacter pylori

The reason I received the Nobel Prize

If you know what you want to know, the Internet is probably a better source of information than books.

If you're curious about Helicobacter pylori, just type the word "helicobacter" into the internet and you'll see a screen full of information about what it looks like, what its characteristics are, who discovered it, and what diseases it causes.

That would probably be faster and more accurate than searching for a book.

So what should we look for in a book? Helicobacter pylori lives in the human stomach, and the discovery of it warrants a Nobel Prize? Was this bacterium so difficult to find? Or is there another reason? These days, health screenings include Helicobacter pylori testing, but was that such a daunting task in the 1980s? The Nobel Prize is often awarded for groundbreaking research that revolutionizes a field. But is the discovery of Helicobacter pylori even that significant? What are the implications of this discovery, its place in the study of pathogens, and its significance? Isn't what we want from a book not just to present well-organized facts in an accessible manner, but also to understand the context, impact, ramifications, and connections of those facts? This is probably not easily conveyed in a brief, three-line summary.

Isn't this exactly what we want from a book? This book is permeated with the effort to bring out these unique qualities that only a book can offer.

Why are Korean scientists mentioned in popular science books?

I wonder if the research results will come out

If you read general science books, you will rarely encounter Korean scientists.

Perhaps it is because we do not yet have the resources to cover textbook-level verified stories in a general-level science book.

However, I also think that even if they are not famous scientists or engineers who deserve a chapter or subheading, if they are a scientist with some level of verification, they would be worthy of being included in a general-level science book.

I often see foreign research results cited as the basis for explanations, but there are probably quite a few Korean scientists in each field who have produced results at a similar level.

I heard that our universities and research institutes have many talented researchers, and that they have a considerable amount of space and budget for research and experiments.

But why aren't there any Korean scientists named? Newspaper articles and broadcasts show Korean researchers publishing numerous papers and often producing noteworthy results. But why do popular science books only feature names from the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Japan, and China? There are also quite a few Brazilians and Indians, so why aren't there any Koreans? Surely, there must have been quite a few noteworthy results among the papers published while studying or working as doctoral students abroad.

But why aren't these studies mentioned in popular science books written by domestic authors?

Why do Korean authors of general science books avoid including the names of their colleagues, seniors, or juniors? The reasons may be numerous, but one thing is clear: while scholars from many other countries appear, Koreans don't appear nearly as often.

However, this book contains several research results from active domestic scientists.

Nice and friendly.

Wouldn't it be better to cite and mention Korean authors' work, if at all possible? It might be possible to avoid mentioning anything, but when similar research results are attributed to Korean researchers, interest is immediately drawn, and any Korean reader will likely be even more intrigued.

This book introduces Professor Richard Lenski, who is well known for his long-term evolution experiments on E. coli, and describes the research that Professor Jihyun Kim of Yonsei University conducted with Professor Lenski.

Domestic scholars also appear in chapters on quorum sensing, antibiotic resistance, and microbiome research.

Now that the number of domestic researchers writing for the general public is increasing, I expect that the number of stories about their colleagues, seniors, and juniors will gradually increase.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: January 30, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 344 pages | 534g | 143*215*30mm

- ISBN13: 9788998243296

- ISBN10: 8998243296

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)