How to read numbers without being fooled by them

|

Description

Book Introduction

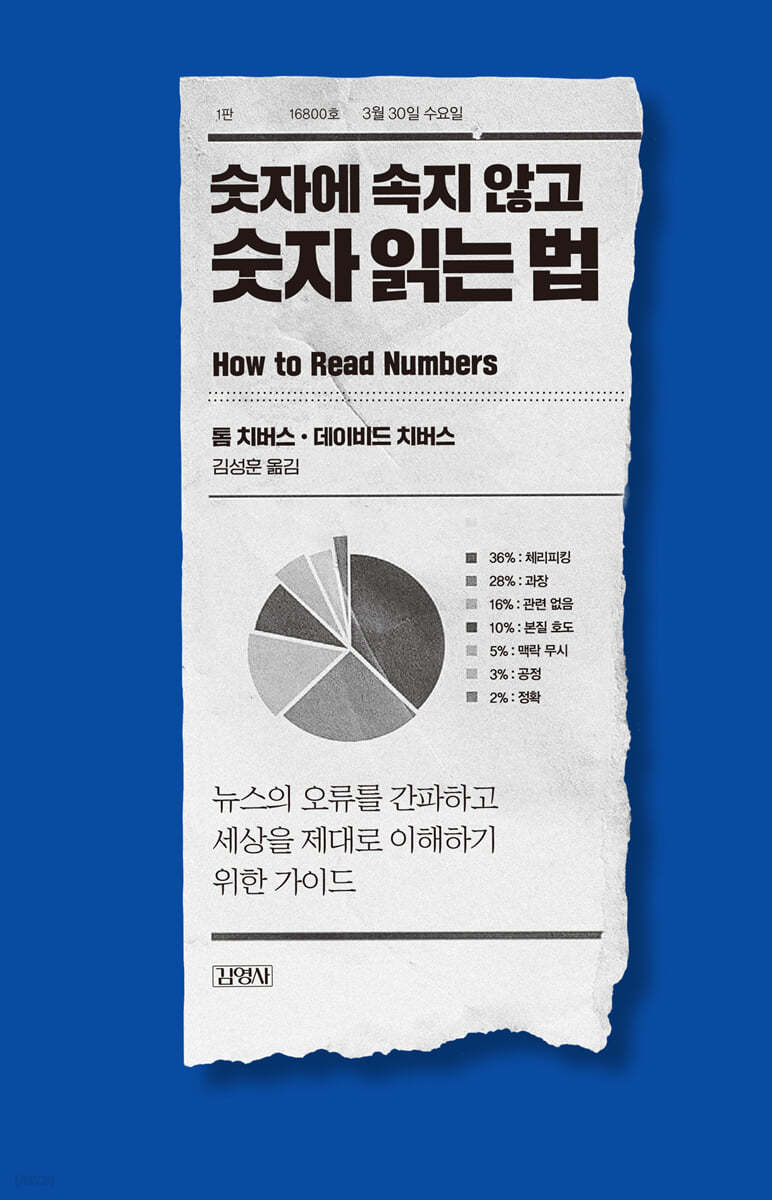

“How are numbers created, how are they used, and how do they go wrong?” How to distinguish between trustworthy and unreliable numbers in the news From opinion polls to crime rates, economic growth rates, and COVID-19 cases, in a world filled with numbers, how can we truly understand the situation and make better decisions? "How to Read the Numbers Without Being Fooled" offers tips for discerning inaccurate or contradictory results wrapped in plausible figures and accurately grasping the information you need. It explains how seemingly simple numbers can be deceptive and lead to errors, and discusses what to be careful of when dealing with numbers in the news and how to detect the hidden intentions behind them. Using recent real news headlines from the UK, such as [The Guardian], [The Daily Telegraph], and [The Times], as examples, it explains essential statistical principles. Readers will be so entertained that they won't even realize how much they've learned, from basic statistical terms like median and standard deviation to concepts like p-value, cherry-picking, sampling bias, and Bayes' theorem. We've included a 'Statistics Style Guide' as an appendix, which will be a useful guide for those who work with numbers. |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

introduction

Chapter 1: How Numbers Understand the Essence

Chapter 2 Anecdotal Evidence

Chapter 3 Sample Size

Chapter 4 Biased Samples

Chapter 5 Statistical Significance

Chapter 6 Effect Size

Chapter 7 Confounding Variables

Chapter 8 Causality

Chapter 9: Is This a Big Number?

Chapter 10 Bayes' Theorem

Chapter 11 Absolute and Relative Risk

Chapter 12: Has the Measurement Object Changed?

Chapter 13 Ranking

Chapter 14: Does This Represent the Literature?

Chapter 15: The Demand for Newness

Chapter 16 Cherry Picking

Chapter 17 Prediction

Chapter 18: Assumptions in the Model

Chapter 19: The Texas Sharpshooter Fallacy

Chapter 20: Survivorship Bias

Chapter 21 Collision Deflection

Chapter 22: Goodhart's Law

Conclusion and Statistics Style Guide

Acknowledgements

Translator's Note

main

Search

Chapter 1: How Numbers Understand the Essence

Chapter 2 Anecdotal Evidence

Chapter 3 Sample Size

Chapter 4 Biased Samples

Chapter 5 Statistical Significance

Chapter 6 Effect Size

Chapter 7 Confounding Variables

Chapter 8 Causality

Chapter 9: Is This a Big Number?

Chapter 10 Bayes' Theorem

Chapter 11 Absolute and Relative Risk

Chapter 12: Has the Measurement Object Changed?

Chapter 13 Ranking

Chapter 14: Does This Represent the Literature?

Chapter 15: The Demand for Newness

Chapter 16 Cherry Picking

Chapter 17 Prediction

Chapter 18: Assumptions in the Model

Chapter 19: The Texas Sharpshooter Fallacy

Chapter 20: Survivorship Bias

Chapter 21 Collision Deflection

Chapter 22: Goodhart's Law

Conclusion and Statistics Style Guide

Acknowledgements

Translator's Note

main

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

In the run-up to the 2019 UK general election, Jeremy Corbyn, then leader of the Labour Party, and Boris Johnson, then Prime Minister and leader of the Tory Party, held a televised debate.

A YouGov poll conducted after the debate found that 48 percent thought Johnson did better, 46 percent thought Corbyn did better, and 7 percent were unsure (for a total of 101 percent).

(This is due to rounding), and opinions were reported to be almost evenly split on who would win the debate.

There has been a debate online about this.

In one tweet that went viral (it has over 16,000 retweets as of this writing), he pointed out that other polls had produced very different results (see figure on the next page).

Four out of five polls showed Corbyn winning the debate handily.

There was only one poll that produced the opposite result, and the sample size was far smaller than the others.

Yet, public news channels only cited this poll.

Does this mean the news channel is biased against Corbyn?

--- p.47

It took months for conscientious researchers and experienced science journalists with statistical minds to uncover Wansink's actions.

Most journalists who write about science receive news stories from press releases sent to the media as they are received.

So even if they get the data set, they can't detect p-hacking.

And usually, we don't even have access to a dataset.

Studies that p-hack have an unfair advantage.

Because the research results don't have to be true, it's easier to fill them with exciting content, which is why they're often covered in the news.

It is not easy for readers to detect such p-hacking by watching the news.

However, it is important to keep in mind that just because something is statistically significant does not mean that it is meaningful, important, or true.

--- p.65

How large does a number have to be to be considered large? In fact, there is no such standard.

In fact, the size and other properties of a number vary depending on the context.

100 is a very large number for the number of people that can fit in a house, but it is a very small number for the number of stars in the galaxy.

2 is a small number in terms of the number of hairs on your head, but it is a large number in terms of the number of Nobel Prizes you have received in your lifetime or the number of bullet wounds to the abdomen.

However, the numbers that appear in the news are often presented without context, so you have to figure out for yourself whether they are large numbers or not.

The most important part in context is the denominator.

The denominator is the number below the middle line of a fraction.

In 3?4, 4 is the denominator, and in 5?8, 8 is the numerator (the number above the line is called the numerator).

You probably haven't used the term denominator much since your math days in school, but it's incredibly important when understanding numbers you see in the news.

Figuring out which numbers are big and which are small ultimately comes down to figuring out what the most appropriate denominator is.

--- p.92

For example, the University of Manchester, where David Chivers, one of the authors of this book, studied, was ranked 27th in the world university rankings, but 40th in the Guardian's list of UK universities.

This is clearly an absurd result.

If there are 39 universities in the UK better than the University of Manchester, then there can only be 26 better universities in the world.

Because Britain is included in the whole world.

Another odd case is King's College London, where author Tom Chivers attended.

It ranked 63rd in the UK but 31st worldwide.

The reason for these counterintuitive results is that there are different judgments about which items to include and which items to weight.

If we prioritize 'student satisfaction' over 'academic reputation', the results will be different.

Depending on your own judgment about what to consider, the situation can vary greatly.

This is not to say that all rankings are wrong, but rankings should not be viewed as sacrosanct truths.

--- p.129

More importantly, thousands of other lawmakers, journalists, scholars, and others have made all sorts of announcements about what will and will not happen in the future.

Among them, there is bound to always be a sound that is right.

The odds of you winning the lottery are very slim, but someone probably will.

Someone wins the lottery without any special insight.

As we saw in Chapter 17, predicting the future is difficult.

The economy is harder to predict.

If you can effectively predict the economy, it's not difficult to become a millionaire.

To have predicted nine out of five recessions, or to have been wrong only four times, is actually a remarkably good achievement.

But if you try to figure out who predicted something after it happened, you're likely to fall into the Texas Sharpshooter fallacy.

It's like drawing a target on data that coincidentally matches the result among randomly scattered data.

--- p.188

It is not easy to detect collision bias.

For example, some scientists argue that conflict bias is also behind the 'obesity paradox'.

The obesity paradox refers to the phenomenon where obese people appear to be less likely to die from diabetes than people of normal weight.

Some people claim that this is not true.

There is ongoing debate about this.

It seems unfair to ask journalists and readers to define what collision bias is and what isn't when even scientists can't quite determine for sure.

However, it is important to recognize that correlations can be misleading in several ways, even when studies do their best to control for other factors.

Sometimes, trying to control factors to make things better can actually make things worse.

--- p.210

Evaluation criteria are multifaceted and complex, making them difficult to define, but they are merely proxies used to identify some characteristic that actually exists.

What really matters is the characteristics.

Even people in the media easily forget that.

So the media only talks about how many pieces of personal protective equipment are produced, not whether each piece is an N95 mask or a pair of rubber gloves.

There are ways to circumvent Goodhart's Law to some extent.

This can be alleviated by frequently changing the evaluation criteria or using multiple evaluation criteria.

But no measurement method can fully capture the underlying reality.

Because reality is always more complicated.

Author Will Kurt once said on Twitter:

“Finding the perfect summary statistic is like finding a cover copy of a book that lets you know what it’s about without having to read it.”

A YouGov poll conducted after the debate found that 48 percent thought Johnson did better, 46 percent thought Corbyn did better, and 7 percent were unsure (for a total of 101 percent).

(This is due to rounding), and opinions were reported to be almost evenly split on who would win the debate.

There has been a debate online about this.

In one tweet that went viral (it has over 16,000 retweets as of this writing), he pointed out that other polls had produced very different results (see figure on the next page).

Four out of five polls showed Corbyn winning the debate handily.

There was only one poll that produced the opposite result, and the sample size was far smaller than the others.

Yet, public news channels only cited this poll.

Does this mean the news channel is biased against Corbyn?

--- p.47

It took months for conscientious researchers and experienced science journalists with statistical minds to uncover Wansink's actions.

Most journalists who write about science receive news stories from press releases sent to the media as they are received.

So even if they get the data set, they can't detect p-hacking.

And usually, we don't even have access to a dataset.

Studies that p-hack have an unfair advantage.

Because the research results don't have to be true, it's easier to fill them with exciting content, which is why they're often covered in the news.

It is not easy for readers to detect such p-hacking by watching the news.

However, it is important to keep in mind that just because something is statistically significant does not mean that it is meaningful, important, or true.

--- p.65

How large does a number have to be to be considered large? In fact, there is no such standard.

In fact, the size and other properties of a number vary depending on the context.

100 is a very large number for the number of people that can fit in a house, but it is a very small number for the number of stars in the galaxy.

2 is a small number in terms of the number of hairs on your head, but it is a large number in terms of the number of Nobel Prizes you have received in your lifetime or the number of bullet wounds to the abdomen.

However, the numbers that appear in the news are often presented without context, so you have to figure out for yourself whether they are large numbers or not.

The most important part in context is the denominator.

The denominator is the number below the middle line of a fraction.

In 3?4, 4 is the denominator, and in 5?8, 8 is the numerator (the number above the line is called the numerator).

You probably haven't used the term denominator much since your math days in school, but it's incredibly important when understanding numbers you see in the news.

Figuring out which numbers are big and which are small ultimately comes down to figuring out what the most appropriate denominator is.

--- p.92

For example, the University of Manchester, where David Chivers, one of the authors of this book, studied, was ranked 27th in the world university rankings, but 40th in the Guardian's list of UK universities.

This is clearly an absurd result.

If there are 39 universities in the UK better than the University of Manchester, then there can only be 26 better universities in the world.

Because Britain is included in the whole world.

Another odd case is King's College London, where author Tom Chivers attended.

It ranked 63rd in the UK but 31st worldwide.

The reason for these counterintuitive results is that there are different judgments about which items to include and which items to weight.

If we prioritize 'student satisfaction' over 'academic reputation', the results will be different.

Depending on your own judgment about what to consider, the situation can vary greatly.

This is not to say that all rankings are wrong, but rankings should not be viewed as sacrosanct truths.

--- p.129

More importantly, thousands of other lawmakers, journalists, scholars, and others have made all sorts of announcements about what will and will not happen in the future.

Among them, there is bound to always be a sound that is right.

The odds of you winning the lottery are very slim, but someone probably will.

Someone wins the lottery without any special insight.

As we saw in Chapter 17, predicting the future is difficult.

The economy is harder to predict.

If you can effectively predict the economy, it's not difficult to become a millionaire.

To have predicted nine out of five recessions, or to have been wrong only four times, is actually a remarkably good achievement.

But if you try to figure out who predicted something after it happened, you're likely to fall into the Texas Sharpshooter fallacy.

It's like drawing a target on data that coincidentally matches the result among randomly scattered data.

--- p.188

It is not easy to detect collision bias.

For example, some scientists argue that conflict bias is also behind the 'obesity paradox'.

The obesity paradox refers to the phenomenon where obese people appear to be less likely to die from diabetes than people of normal weight.

Some people claim that this is not true.

There is ongoing debate about this.

It seems unfair to ask journalists and readers to define what collision bias is and what isn't when even scientists can't quite determine for sure.

However, it is important to recognize that correlations can be misleading in several ways, even when studies do their best to control for other factors.

Sometimes, trying to control factors to make things better can actually make things worse.

--- p.210

Evaluation criteria are multifaceted and complex, making them difficult to define, but they are merely proxies used to identify some characteristic that actually exists.

What really matters is the characteristics.

Even people in the media easily forget that.

So the media only talks about how many pieces of personal protective equipment are produced, not whether each piece is an N95 mask or a pair of rubber gloves.

There are ways to circumvent Goodhart's Law to some extent.

This can be alleviated by frequently changing the evaluation criteria or using multiple evaluation criteria.

But no measurement method can fully capture the underlying reality.

Because reality is always more complicated.

Author Will Kurt once said on Twitter:

“Finding the perfect summary statistic is like finding a cover copy of a book that lets you know what it’s about without having to read it.”

--- p.218

Publisher's Review

“How are numbers created, how are they used, and how do they go wrong?”

How to distinguish between trustworthy and unreliable numbers in the news

★★★ “You won’t even realize how much you’re learning because it’s so much fun to read.”

Tim Harford (author of The Economics Concert and senior columnist for the Financial Times)

From opinion polls to crime rates, economic growth rates, and confirmed COVID-19 cases, how can we truly understand the situation and make better decisions in a world filled with numbers? We encounter countless numbers every day.

Countless statistics appear in news headlines, and the press and media compete to expose shocking figures. On social media and YouTube, sensational figures are spread in a distorted form.

There has never been a time when the ability to discern truth from falsehood was more necessary than today.

Furthermore, as we navigate the turbulent times of COVID-19, the world has been forced to quickly learn about statistical concepts such as the reproduction number and the total number of deaths.

Statistician Frederick Mosteller said, “It is difficult to tell the truth without statistics,” and we have reached an age where we must find the truth in various statistical figures.

In times like these, the ability to read numbers is essential.

The ability to read numbers accurately is a powerful tool for understanding the world.

"How to Read Numbers Without Being Fooled by Them" is a guide that shows you how to identify inaccurate or contradictory results wrapped in fancy numbers and accurately grasp the information you need.

Explains how seemingly simple numbers can be deceptive and lead to errors.

It explains essential statistical principles using recent actual news headlines from the UK, such as [The Guardian], [The Daily Telegraph], and [The Times], so that anyone can easily understand and enjoy reading it, even without any mathematical knowledge.

“It deserves to be called the British version of [Freakonomics]!”

A must-read for anyone who works with numbers

This book stands out for its friendly and pleasant narrative by Tom Chivers, who was selected as 'Science Writer of the Year' in the UK and won the British Press Award, and his cousin David Chivers, professor of economics at Durham University.

From basic statistical terms like median and standard deviation to statistical concepts like p-value, cherry-picking, sampling bias, and Bayes' theorem that you might not normally understand, this book covers the entire range of knowledge in statistics in an easy-to-understand manner in 22 short chapters. Thanks to British humor and engaging examples, readers will be so entertained that they won't even realize how much they're learning.

The "Statistical Style Guide" included in the appendix presents 11 key points to keep in mind, such as "Provide context for numbers," "Present absolute risks as well as relative risks," and "Present confidence intervals rather than just numbers as forecasts," which will be useful guidelines for anyone who works with numbers.

Inside the real news headlines from the UK

Digging into the strange numbers

This book features exciting, up-to-date news stories from real-life Britain.

These are examples that we can commonly see in our country, from election polls to weather forecasts and economic indicators, so we can read them with greater empathy.

The author corrects errors in numbers in the news and explains how to detect hidden intentions behind numbers.

● The values can completely change depending on the measurement target and method.

In Britain, articles with headlines like “Autism is rapidly spreading, affecting 1 in 54” (Chapter 12) were published.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the rate of autism has increased dramatically, from 1 in 150 in 2000 to 1 in 54 in 2016. Many experts and the media have pointed to heavy metal pollution, pesticides, and even “cold parents” as causes.

But the cause was simple.

This was because the medical community had been expanding the definition of autism and conducting diagnostic tests on more children.

Because numbers can change depending on the measurement target or method, it's important to be mindful of cases where figures change dramatically, such as "hate crimes double in five years" or "COVID-19 deaths surge."

● The fallacy of survivor bias, fitting in filtered data

The article “2,800 Common Traits of Bestsellers Revealed” is also completely wrong (Chapter 20).

It's no different than having 1,000 people wearing different colored hats roll dice, and then seeing the person wearing the orange hat who rolled a six four times in a row and saying, "The secret to rolling sixes in a row is wearing an orange hat."

Let's say you investigate a vicious criminal and discover that he likes to play violent games.

This is similar to saying, “The more violent games you enjoy, the more likely you are to become a criminal.”

This is a classic example of 'survivor bias', which biases a sample towards a particular outcome.

We must be aware that this error of generalizing from a small number of successful cases is a frequent occurrence.

● There is an uncertainty interval behind the exact number.

The UK Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts economic growth in 2020 at 1.2 percent, with an uncertainty range of -0.8 to 3.2 percent (Chapter 17).

In fact, this uncertainty interval figure has a very large margin of error, somewhere between a severe recession and a massive boom, but only the middle figure of 1.2 percent was reported in the headlines.

The numbers in headlines like “COVID-19 deaths to exceed 500,000” and “Unemployment rate to fall by 2%” are merely the middle values in the uncertainty range.

It is dangerous to report only definitive numerical forecasts.

The media has a duty to report on these areas of uncertainty as well.

How to be deceived by numbers, how not to be deceived by numbers

The author reveals in detail the tricks of numbers that we have been deceived by without even noticing.

It reminds us which parts of the numbers are distorted and how we should be wary.

One of them is 'cherry picking', which involves choosing only the starting and ending points that are advantageous to oneself (Chapter 16).

For example, if a current government official wanted to claim that child poverty had improved, they would likely start with the year in which the child poverty rate was highest, while an opposition party member would likely start with the year in which the child poverty rate was particularly low.

In other words, if you pick out data that pops out, you can tell a story that obscures the truth.

In addition, we cover using biased results from studies with small samples (Chapter 4), chopping data until something emerges and creating desired numbers (Chapter 5), disguising simple correlations as causation (Chapter 8), and promoting the idea that something is happening when in fact nothing is happening (Chapter 19).

This book is recommended to everyone who responsibly handles numbers: from journalists who write articles and deliver the news, to media companies that send out newsletters, to politicians who announce policies with numbers, to influencers who work on social media and YouTube, to content editors who are sensitive to trends and issues, to office workers who check the daily news on their commute.

“I am very pleased to see the publication of this book, which will be of great help in acquiring a basic understanding of statistics.

This book will help you develop the ability to question numbers in a healthy way.

“This is an excellent book for those who want to learn how to read statistics but don’t plan on becoming a statistics expert.” (From the translator’s note)

How to distinguish between trustworthy and unreliable numbers in the news

★★★ “You won’t even realize how much you’re learning because it’s so much fun to read.”

Tim Harford (author of The Economics Concert and senior columnist for the Financial Times)

From opinion polls to crime rates, economic growth rates, and confirmed COVID-19 cases, how can we truly understand the situation and make better decisions in a world filled with numbers? We encounter countless numbers every day.

Countless statistics appear in news headlines, and the press and media compete to expose shocking figures. On social media and YouTube, sensational figures are spread in a distorted form.

There has never been a time when the ability to discern truth from falsehood was more necessary than today.

Furthermore, as we navigate the turbulent times of COVID-19, the world has been forced to quickly learn about statistical concepts such as the reproduction number and the total number of deaths.

Statistician Frederick Mosteller said, “It is difficult to tell the truth without statistics,” and we have reached an age where we must find the truth in various statistical figures.

In times like these, the ability to read numbers is essential.

The ability to read numbers accurately is a powerful tool for understanding the world.

"How to Read Numbers Without Being Fooled by Them" is a guide that shows you how to identify inaccurate or contradictory results wrapped in fancy numbers and accurately grasp the information you need.

Explains how seemingly simple numbers can be deceptive and lead to errors.

It explains essential statistical principles using recent actual news headlines from the UK, such as [The Guardian], [The Daily Telegraph], and [The Times], so that anyone can easily understand and enjoy reading it, even without any mathematical knowledge.

“It deserves to be called the British version of [Freakonomics]!”

A must-read for anyone who works with numbers

This book stands out for its friendly and pleasant narrative by Tom Chivers, who was selected as 'Science Writer of the Year' in the UK and won the British Press Award, and his cousin David Chivers, professor of economics at Durham University.

From basic statistical terms like median and standard deviation to statistical concepts like p-value, cherry-picking, sampling bias, and Bayes' theorem that you might not normally understand, this book covers the entire range of knowledge in statistics in an easy-to-understand manner in 22 short chapters. Thanks to British humor and engaging examples, readers will be so entertained that they won't even realize how much they're learning.

The "Statistical Style Guide" included in the appendix presents 11 key points to keep in mind, such as "Provide context for numbers," "Present absolute risks as well as relative risks," and "Present confidence intervals rather than just numbers as forecasts," which will be useful guidelines for anyone who works with numbers.

Inside the real news headlines from the UK

Digging into the strange numbers

This book features exciting, up-to-date news stories from real-life Britain.

These are examples that we can commonly see in our country, from election polls to weather forecasts and economic indicators, so we can read them with greater empathy.

The author corrects errors in numbers in the news and explains how to detect hidden intentions behind numbers.

● The values can completely change depending on the measurement target and method.

In Britain, articles with headlines like “Autism is rapidly spreading, affecting 1 in 54” (Chapter 12) were published.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the rate of autism has increased dramatically, from 1 in 150 in 2000 to 1 in 54 in 2016. Many experts and the media have pointed to heavy metal pollution, pesticides, and even “cold parents” as causes.

But the cause was simple.

This was because the medical community had been expanding the definition of autism and conducting diagnostic tests on more children.

Because numbers can change depending on the measurement target or method, it's important to be mindful of cases where figures change dramatically, such as "hate crimes double in five years" or "COVID-19 deaths surge."

● The fallacy of survivor bias, fitting in filtered data

The article “2,800 Common Traits of Bestsellers Revealed” is also completely wrong (Chapter 20).

It's no different than having 1,000 people wearing different colored hats roll dice, and then seeing the person wearing the orange hat who rolled a six four times in a row and saying, "The secret to rolling sixes in a row is wearing an orange hat."

Let's say you investigate a vicious criminal and discover that he likes to play violent games.

This is similar to saying, “The more violent games you enjoy, the more likely you are to become a criminal.”

This is a classic example of 'survivor bias', which biases a sample towards a particular outcome.

We must be aware that this error of generalizing from a small number of successful cases is a frequent occurrence.

● There is an uncertainty interval behind the exact number.

The UK Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts economic growth in 2020 at 1.2 percent, with an uncertainty range of -0.8 to 3.2 percent (Chapter 17).

In fact, this uncertainty interval figure has a very large margin of error, somewhere between a severe recession and a massive boom, but only the middle figure of 1.2 percent was reported in the headlines.

The numbers in headlines like “COVID-19 deaths to exceed 500,000” and “Unemployment rate to fall by 2%” are merely the middle values in the uncertainty range.

It is dangerous to report only definitive numerical forecasts.

The media has a duty to report on these areas of uncertainty as well.

How to be deceived by numbers, how not to be deceived by numbers

The author reveals in detail the tricks of numbers that we have been deceived by without even noticing.

It reminds us which parts of the numbers are distorted and how we should be wary.

One of them is 'cherry picking', which involves choosing only the starting and ending points that are advantageous to oneself (Chapter 16).

For example, if a current government official wanted to claim that child poverty had improved, they would likely start with the year in which the child poverty rate was highest, while an opposition party member would likely start with the year in which the child poverty rate was particularly low.

In other words, if you pick out data that pops out, you can tell a story that obscures the truth.

In addition, we cover using biased results from studies with small samples (Chapter 4), chopping data until something emerges and creating desired numbers (Chapter 5), disguising simple correlations as causation (Chapter 8), and promoting the idea that something is happening when in fact nothing is happening (Chapter 19).

This book is recommended to everyone who responsibly handles numbers: from journalists who write articles and deliver the news, to media companies that send out newsletters, to politicians who announce policies with numbers, to influencers who work on social media and YouTube, to content editors who are sensitive to trends and issues, to office workers who check the daily news on their commute.

“I am very pleased to see the publication of this book, which will be of great help in acquiring a basic understanding of statistics.

This book will help you develop the ability to question numbers in a healthy way.

“This is an excellent book for those who want to learn how to read statistics but don’t plan on becoming a statistics expert.” (From the translator’s note)

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: March 30, 2022

- Page count, weight, size: 268 pages | 294g | 135*210*20mm

- ISBN13: 9788934961734

- ISBN10: 8934961732

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)