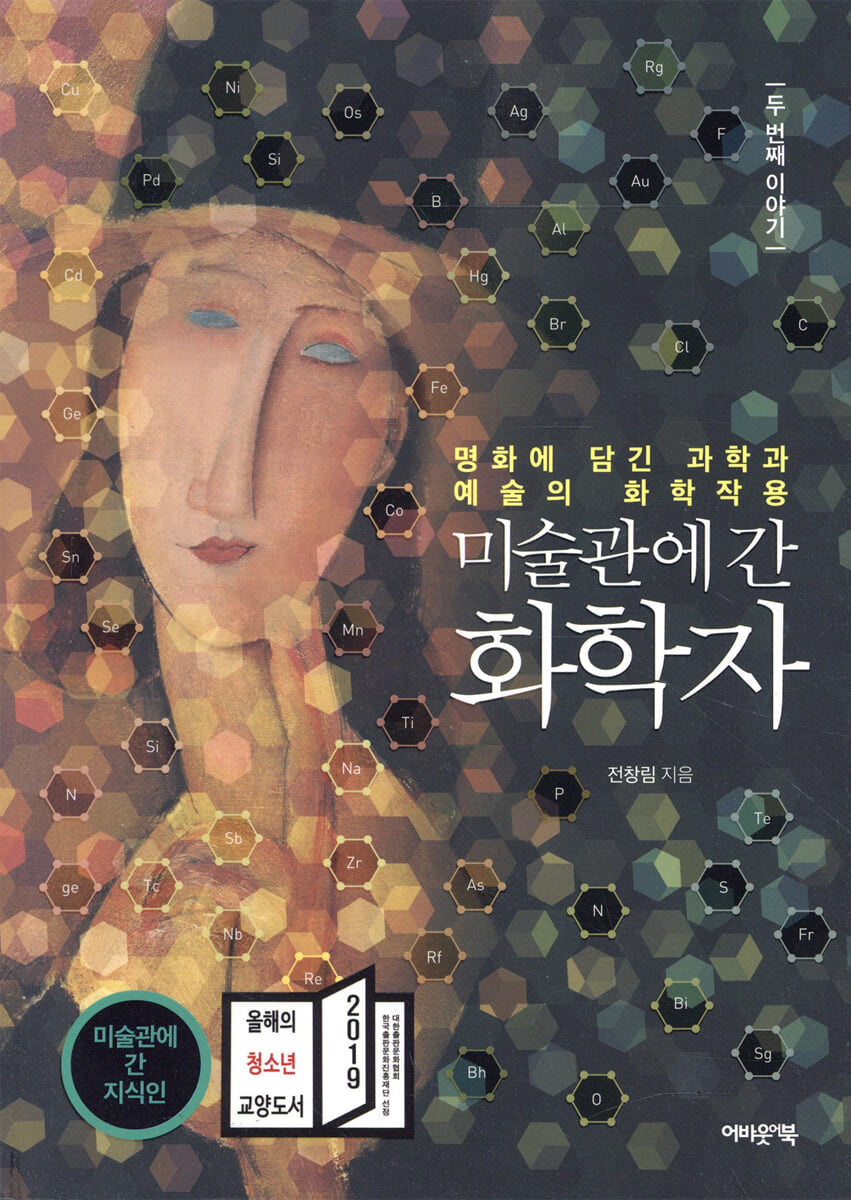

The Second Story of the Chemist Who Went to the Art Museum

|

Description

Book Introduction

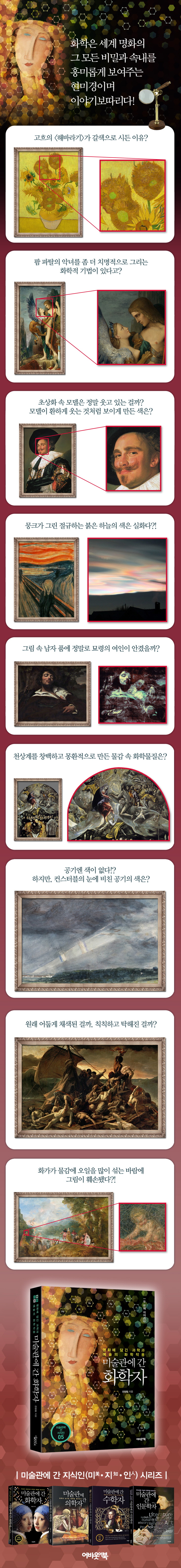

What on earth happened to Van Gogh's brown, withered 'Sunflowers'?

What is the chemical technique that makes the femme fatale look even more deadly?

In a world filled with fine dust, what is the one painting that stands out?

Enjoy the chemical play that has evolved into an immortal masterpiece.

It has been over ten years since the publication of “The Chemist Who Went to the Art Museum: The First Story.”

Over the not-so-short period of time in which even mountains and rivers change, it has received undeserved praise from the scientific, artistic, and educational communities.

Thanks to this, it has been loved by many readers and has been reprinted many times, and I have had the precious opportunity to publish 『The Chemist Who Went to the Art Museum: The Second Story』.

In 『The Chemist Who Went to the Art Museum: The Second Story』, the story of chemistry in art is just as exciting as the first part.

In 'What Happened to the Brown, Withered Sunflower?', the reason why Van Gogh's 'Sunflowers' became darker over time was analyzed.

A chemist's perspective on why Van Gogh was so obsessed with chrome yellow under the intense sun of Arles.

In 'The Color of the Screaming Sky', meteorologists' very unique research on the red sky that appears in Munch's 'The Scream' is introduced.

While discussing the 'Black Paintings' of Spanish national artist Goya, he also explained in an easy-to-understand way why a completely dark color that absorbs all light cannot exist.

The never-ending debate in art history, the 'battle between line and color,' is also very interesting.

Going a step further from the classic debates in art history, he unravels how artistic thinking can be scientifically extended by deriving mathematics from lines and chemistry from colors.

In addition, the story of 'gold leaf' that the 'golden painter' Klimt used in his works, the color of the air painted by the British landscape painter Constable, and the chemical technique used to paint a fatal femme fatale, etc., added to the fun of art appreciation with chemical episodes hidden in immortal masterpieces.

What is the chemical technique that makes the femme fatale look even more deadly?

In a world filled with fine dust, what is the one painting that stands out?

Enjoy the chemical play that has evolved into an immortal masterpiece.

It has been over ten years since the publication of “The Chemist Who Went to the Art Museum: The First Story.”

Over the not-so-short period of time in which even mountains and rivers change, it has received undeserved praise from the scientific, artistic, and educational communities.

Thanks to this, it has been loved by many readers and has been reprinted many times, and I have had the precious opportunity to publish 『The Chemist Who Went to the Art Museum: The Second Story』.

In 『The Chemist Who Went to the Art Museum: The Second Story』, the story of chemistry in art is just as exciting as the first part.

In 'What Happened to the Brown, Withered Sunflower?', the reason why Van Gogh's 'Sunflowers' became darker over time was analyzed.

A chemist's perspective on why Van Gogh was so obsessed with chrome yellow under the intense sun of Arles.

In 'The Color of the Screaming Sky', meteorologists' very unique research on the red sky that appears in Munch's 'The Scream' is introduced.

While discussing the 'Black Paintings' of Spanish national artist Goya, he also explained in an easy-to-understand way why a completely dark color that absorbs all light cannot exist.

The never-ending debate in art history, the 'battle between line and color,' is also very interesting.

Going a step further from the classic debates in art history, he unravels how artistic thinking can be scientifically extended by deriving mathematics from lines and chemistry from colors.

In addition, the story of 'gold leaf' that the 'golden painter' Klimt used in his works, the color of the air painted by the British landscape painter Constable, and the chemical technique used to paint a fatal femme fatale, etc., added to the fun of art appreciation with chemical episodes hidden in immortal masterpieces.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Preface : Chemistry, Art, and Life Stories in Masterpieces

Chapter 1: On God and Man

· The Secret of the Paints that Painted the Heavenly Realm _ El Greco

A Great Painter Who Fell into Mannerism? _Art History Talk at the Art Museum Cafe

Light and Darkness Projected in Art and Science _Masaccio

· Dialectics of Venus _ Botticelli

· Nude dressed in art _ Titian

A Chemical Warning Against Perverse Sexual Desires _ Science Talk at the Art Museum Cafe

· Light Scanning the Mass of the Body _Tintoretto

· The painter of light lost in the darkness _ Caravaggio

· Painter of flesh _ Rubens

Personal Color and Color Science _ Science Talk at the Art Museum Cafe

Chapter 2: On Lines and Colors

· Report on the color of a bright smile _ Hals

· Drawing the harmonious principles of all things in the world _Poussin

· The metaphor of light and color in the greatest masterpieces _Velázquez

In [Las Meninas], is the king's position viewed by Velazquez to the left or the right?

_Science Talk at the Art Museum Cafe

· In the unfamiliar landscape of a lonely painter _Lauisdal

· A Rococo portrait as vain as faded paint _ Bateau

· A subtle and dense harmony of green and pink _Fragonard

· The Battle of Line and Color _ Ingres

Is it the line of mathematics or the color of chemistry? _Science talk at the art museum cafe.

Chapter 3: On Reason and Emotion

· Painter of Darkness _ Goya

Black and Gray Stories _ Science Talk at the Art Museum Cafe

· On the Paints That Faded Great Masterpieces _Gericault

· The Color of Air _ Constable

· Drawing Power _Turner

The Power of Steam _ Science Talk at the Art Museum Cafe

Bury the Angel! _Courbet

A young woman in the arms of a wounded man? _Science Talk at the Art Museum Cafe

· Misunderstandings and Truths Concerning a Pastoral Painting _ Millet

· The Guardian of Academism _ Bouguereau

History of the Academy _ Science Talks at the Art Museum Cafe

Chapter 4: On Light and Darkness

Plagiarism or Re-creation? _Manet

The Plagiarism Controversy Among Giants: Science Talk at the Art Museum Cafe

· Chemical techniques for drawing villainesses _Moro

· What Happened to the Brown, Withered Sunflower? _Van Gogh

Van Gogh's [Sunflowers] collection

A great work? A huge painting! _Gauguin

· The Color of the Screaming Sky _ Munch

· To divide or to separate! _Klimt

Separatist Stories _ Art History Talks at the Art Museum Cafe

· The saddest chemical reaction in art history _ Modigliani

Is Love Chemistry Too? _Science Talk at the Art Museum Cafe

Chapter 1: On God and Man

· The Secret of the Paints that Painted the Heavenly Realm _ El Greco

A Great Painter Who Fell into Mannerism? _Art History Talk at the Art Museum Cafe

Light and Darkness Projected in Art and Science _Masaccio

· Dialectics of Venus _ Botticelli

· Nude dressed in art _ Titian

A Chemical Warning Against Perverse Sexual Desires _ Science Talk at the Art Museum Cafe

· Light Scanning the Mass of the Body _Tintoretto

· The painter of light lost in the darkness _ Caravaggio

· Painter of flesh _ Rubens

Personal Color and Color Science _ Science Talk at the Art Museum Cafe

Chapter 2: On Lines and Colors

· Report on the color of a bright smile _ Hals

· Drawing the harmonious principles of all things in the world _Poussin

· The metaphor of light and color in the greatest masterpieces _Velázquez

In [Las Meninas], is the king's position viewed by Velazquez to the left or the right?

_Science Talk at the Art Museum Cafe

· In the unfamiliar landscape of a lonely painter _Lauisdal

· A Rococo portrait as vain as faded paint _ Bateau

· A subtle and dense harmony of green and pink _Fragonard

· The Battle of Line and Color _ Ingres

Is it the line of mathematics or the color of chemistry? _Science talk at the art museum cafe.

Chapter 3: On Reason and Emotion

· Painter of Darkness _ Goya

Black and Gray Stories _ Science Talk at the Art Museum Cafe

· On the Paints That Faded Great Masterpieces _Gericault

· The Color of Air _ Constable

· Drawing Power _Turner

The Power of Steam _ Science Talk at the Art Museum Cafe

Bury the Angel! _Courbet

A young woman in the arms of a wounded man? _Science Talk at the Art Museum Cafe

· Misunderstandings and Truths Concerning a Pastoral Painting _ Millet

· The Guardian of Academism _ Bouguereau

History of the Academy _ Science Talks at the Art Museum Cafe

Chapter 4: On Light and Darkness

Plagiarism or Re-creation? _Manet

The Plagiarism Controversy Among Giants: Science Talk at the Art Museum Cafe

· Chemical techniques for drawing villainesses _Moro

· What Happened to the Brown, Withered Sunflower? _Van Gogh

Van Gogh's [Sunflowers] collection

A great work? A huge painting! _Gauguin

· The Color of the Screaming Sky _ Munch

· To divide or to separate! _Klimt

Separatist Stories _ Art History Talks at the Art Museum Cafe

· The saddest chemical reaction in art history _ Modigliani

Is Love Chemistry Too? _Science Talk at the Art Museum Cafe

Detailed image

Publisher's Review

“Now that we are moving from the era of experts to the era of cultured people,

“A classy book written by a cultured expert!”

When [The Chemist Who Went to the Art Museum: The First Story] first came out around 2008, many people tilted their heads at the title.

'A chemist at an art museum?' 'Why on earth would a chemist go to an art museum?'

However, “art is an art that is born from chemistry and lives off chemistry.

This is because paint, the main material of art, is a chemical substance.

Everyone clapped their hands in agreement with the author's short comment that "the fading or discoloration of paint on canvas over time is all due to chemical reactions."

This is because even most art experts missed the obvious fact that paint is a chemical and that the discoloration of a painting is a chemical reaction.

The moment you open the book, the story of chemistry hidden in the works of masters from da Vinci to Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Monet, and even Jang Seung-eop and Kim Hong-do is revealed to the world.

In this way, [The Chemist Who Went to the Art Museum] caused a sensation and received rave reviews from all walks of life, including the scientific and artistic communities.

It has also been a bestseller in the science field for the past 12 years, receiving much love from many readers.

According to the author, a university professor, after the book was published, he became known as the “chemist who went to the art museum,” and he has been asked to give lectures on art and chemistry in many places. He also contributes to various media outlets, becoming quite famous (!).

The specialized knowledge of a scientist who had been focusing solely on lectures, research, and writing papers within the ivory tower spread to the general public through its integration with art.

Among the numerous reviews attached to [The Chemist Who Went to the Art Museum], the impressions posted on online bookstores by readers make us nod in agreement as to how this book became a bestseller and has remained a steady seller for over a decade.

“If we define universal knowledge and experience as culture, then it seems that the times are gradually moving from the era of experts to the era of cultured people.

“A classy book written by a cultured expert!”

“If the subject I hated the most in school was chemistry, the subject I liked the most was art.

This book, which combines two subjects that are polar opposites, is a curiosity in itself!”

Amidst praise and support from all walks of life, from the scientific and artistic communities,

[The Chemist Who Went to the Art Museum: Part 2] published!

Thanks to the praise and support from all walks of life in the scientific and artistic communities, I have been given the precious opportunity to publish [The Chemist Who Went to the Art Museum: The Second Story].

We are back with readers with an exciting story of chemistry in art that surpasses the previous installment.

· Painters who could sense the chemical reactions of paints and those who could not

El Greco, a master of Mannerism who was active in the 16th century, used white lead, which is mainly composed of lead (Pb), to create a dreamy atmosphere of the heavenly world in [The Burial of the Count of Orgaz].

The reason why lead paint has a unique pale white color rather than a plain white color is because of the lead component.

However, there is no record in any literature as to whether El Greco accurately understood the chemical composition of lead before using it.

However, the artist's insight into color is often more delicate and sophisticated than any color-related chemical experiment.

This is also the reason why the author, a chemist, leaves the laboratory and heads to the art museum (pp. 20-21).

On the other hand, there are many cases where the work discolors because the artist did not properly understand the properties of the paint.

When French Romantic master Géricault painted his masterpiece [The Raft of the Medusa], he used a pigment called 'bitumen' that produced a brown color. Over time, this caused the painting to crack and turn gray-brown.

Bitumen, also known as bitumen in German, is a dark brown tar produced when natural asphalt or other hydrocarbon-based materials are heated.

Bitumen pigments were popular with British painters in the 18th century, but are now rarely used as paints because of the defects of cracking and discoloration that occur over time.

Although Géricault meticulously prepared for [The Raft of the Medusa] by making numerous sketches, conducting field surveys, and even meticulously observing the process of corpse decomposition, he was not able to do so when it came to paint (pp. 199-200).

· A painter who drew the human body almost perfectly before da Vinci and Michelangelo

The first works that perfectly embody the human body anatomically are Da Vinci's [Vitruvian Man] and Michelangelo's [Statue of David].

However, decades before these two masters, there was someone who drew the human body with near perfection: the Italian painter Masaccio.

Masaccio is famous as the first painter to introduce perspective in his work [Holy Trinity], but few people know that he was the first painter to depict the human body in three dimensions using chiaroscuro.

Some art historians consider chiaroscuro to be the greatest innovation of Renaissance art.

Before Masaccio painted The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, no one had ever achieved this three-dimensionality.

Masaccio was the first to attempt the technique of expressing the three-dimensionality and mass of a cylindrical object by giving light and shade to the bodies of Adam and Eve.

'Light', which distinguishes between brightness and darkness, is also an important field of study in photochemistry, and the effect of light and dark appears depending on the chemical reaction of a substance that absorbs light.

Masaccio was the first painter to realistically express the three-dimensionality and mass of the body by projecting the chemical reaction of light onto the painting (p. 36).

· Why did Van Gogh's [Sunflowers] turn brown and wither?

The part that chemically explains why Van Gogh's [Sunflowers] change color from yellow to brown is also interesting.

Dutch and Belgian scientists have been observing [Sunflowers], which is on display at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, for several years.

As a result, we confirmed that the yellow petals and stems in the picture were turning olive brown.

Scientists have speculated that the cause of the discoloration is that Van Gogh mixed chrome yellow with sulfate white to obtain a bright yellow color when he painted this painting.

It is said that Van Gogh used a large amount of yellow paint containing chromium.

Van Gogh enjoyed using yellow paints, and among them he used chrome yellow a lot.

Chrome yellow is produced by dissolving lead in nitric acid or acetic acid and adding a sodium dichromate (or sodium) solution to form a precipitate.

If an additive such as lead sulfate is added to this reaction or the pH is changed, a color ranging from light yellow to reddish brown is produced.

Chrome Yellow was cheap and was favored by poor artists like Van Gogh.

However, because it contains lead, when it comes into contact with sulfur contained in air pollution, it becomes lead sulfide (PbS), which is black.

Ultimately, as we entered the modern industrial society, the concern about discoloration inevitably grew (p. 298), and Van Gogh's [Sunflowers] were no exception.

· The lines of mathematics or the colors of chemistry? The battle between lines and colors.

Going a step further from the classic debate in art history called the 'battle of lines and colors,' the diagram that derives mathematics from lines and chemistry from colors is also quite refreshing (p. 177).

According to the theory of the superiority of the first and second colors from Poussin to Ingres, painting cannot create any form without drawing.

On the other hand, color is nothing more than an accident that changes with light.

The perfect balance and harmony that Renaissance artists sought to achieve was achieved through lines.

Without lines, we would not be able to devise perspective, symmetry, or ideal human proportions, all of which are based on mathematical thinking and principles.

The counterarguments from the color supremacists, centered around Rubens and Delacroix, are also not insignificant.

There is no such thing as a line; it is merely the boundary where the colored planes meet.

If lines are reason, color is emotion, but art cannot be established with reason alone, which lacks emotion.

Also, the nature and changes of color can be explained through chemistry, because the main material of painting, paint, is a chemical substance (p. 176).

· Chemical episodes about the colors and paints favored by artists

This book, in particular, focuses more heavily on the chemical episodes surrounding the unique colors and paints favored by each artist than the previous volume.

Spain's national painter Goya is famous for his black paintings.

Around 1820, Goya purchased a two-story mansion in the outskirts of Madrid, painted all the walls black, and created a series of 14 paintings, which people called 'Las Pinturas Negras' (Black Paintings) (p. 190).

Goya painted black paintings to convey a contemptuous message of protest against a world polluted by absurdity, but black was not a color that painters were particularly fond of.

As the Impressionist painters explored light, they realized that there was no light that corresponded to black, and so they removed black paint from their palettes.

In this way, black has the property of absorbing all light rather than reflecting it.

However, a completely dark color that absorbs all light does not exist as a substance.

Because completely absorbing light means an infinite space or black hole where no light is reflected (p. 192).

In addition, there are abundant stories of chemistry in painters and their works, such as Dutch portrait painter Frans Hals (page 100), who used orange to highlight the bright smile of the model in his portraits; Rococo painter Fragonard (page 154), who depicted scenes of adultery in a secret and erotic way using the complementary colors of green and pink; British landscape painter John Constable (page 208), who dedicated his life to painting more natural colors than the actual scenery; and Watteau (page 144), who damaged the preservation of his paintings by adding too much oil to his paints to achieve delicate and soft brushstrokes.

“A classy book written by a cultured expert!”

When [The Chemist Who Went to the Art Museum: The First Story] first came out around 2008, many people tilted their heads at the title.

'A chemist at an art museum?' 'Why on earth would a chemist go to an art museum?'

However, “art is an art that is born from chemistry and lives off chemistry.

This is because paint, the main material of art, is a chemical substance.

Everyone clapped their hands in agreement with the author's short comment that "the fading or discoloration of paint on canvas over time is all due to chemical reactions."

This is because even most art experts missed the obvious fact that paint is a chemical and that the discoloration of a painting is a chemical reaction.

The moment you open the book, the story of chemistry hidden in the works of masters from da Vinci to Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Monet, and even Jang Seung-eop and Kim Hong-do is revealed to the world.

In this way, [The Chemist Who Went to the Art Museum] caused a sensation and received rave reviews from all walks of life, including the scientific and artistic communities.

It has also been a bestseller in the science field for the past 12 years, receiving much love from many readers.

According to the author, a university professor, after the book was published, he became known as the “chemist who went to the art museum,” and he has been asked to give lectures on art and chemistry in many places. He also contributes to various media outlets, becoming quite famous (!).

The specialized knowledge of a scientist who had been focusing solely on lectures, research, and writing papers within the ivory tower spread to the general public through its integration with art.

Among the numerous reviews attached to [The Chemist Who Went to the Art Museum], the impressions posted on online bookstores by readers make us nod in agreement as to how this book became a bestseller and has remained a steady seller for over a decade.

“If we define universal knowledge and experience as culture, then it seems that the times are gradually moving from the era of experts to the era of cultured people.

“A classy book written by a cultured expert!”

“If the subject I hated the most in school was chemistry, the subject I liked the most was art.

This book, which combines two subjects that are polar opposites, is a curiosity in itself!”

Amidst praise and support from all walks of life, from the scientific and artistic communities,

[The Chemist Who Went to the Art Museum: Part 2] published!

Thanks to the praise and support from all walks of life in the scientific and artistic communities, I have been given the precious opportunity to publish [The Chemist Who Went to the Art Museum: The Second Story].

We are back with readers with an exciting story of chemistry in art that surpasses the previous installment.

· Painters who could sense the chemical reactions of paints and those who could not

El Greco, a master of Mannerism who was active in the 16th century, used white lead, which is mainly composed of lead (Pb), to create a dreamy atmosphere of the heavenly world in [The Burial of the Count of Orgaz].

The reason why lead paint has a unique pale white color rather than a plain white color is because of the lead component.

However, there is no record in any literature as to whether El Greco accurately understood the chemical composition of lead before using it.

However, the artist's insight into color is often more delicate and sophisticated than any color-related chemical experiment.

This is also the reason why the author, a chemist, leaves the laboratory and heads to the art museum (pp. 20-21).

On the other hand, there are many cases where the work discolors because the artist did not properly understand the properties of the paint.

When French Romantic master Géricault painted his masterpiece [The Raft of the Medusa], he used a pigment called 'bitumen' that produced a brown color. Over time, this caused the painting to crack and turn gray-brown.

Bitumen, also known as bitumen in German, is a dark brown tar produced when natural asphalt or other hydrocarbon-based materials are heated.

Bitumen pigments were popular with British painters in the 18th century, but are now rarely used as paints because of the defects of cracking and discoloration that occur over time.

Although Géricault meticulously prepared for [The Raft of the Medusa] by making numerous sketches, conducting field surveys, and even meticulously observing the process of corpse decomposition, he was not able to do so when it came to paint (pp. 199-200).

· A painter who drew the human body almost perfectly before da Vinci and Michelangelo

The first works that perfectly embody the human body anatomically are Da Vinci's [Vitruvian Man] and Michelangelo's [Statue of David].

However, decades before these two masters, there was someone who drew the human body with near perfection: the Italian painter Masaccio.

Masaccio is famous as the first painter to introduce perspective in his work [Holy Trinity], but few people know that he was the first painter to depict the human body in three dimensions using chiaroscuro.

Some art historians consider chiaroscuro to be the greatest innovation of Renaissance art.

Before Masaccio painted The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, no one had ever achieved this three-dimensionality.

Masaccio was the first to attempt the technique of expressing the three-dimensionality and mass of a cylindrical object by giving light and shade to the bodies of Adam and Eve.

'Light', which distinguishes between brightness and darkness, is also an important field of study in photochemistry, and the effect of light and dark appears depending on the chemical reaction of a substance that absorbs light.

Masaccio was the first painter to realistically express the three-dimensionality and mass of the body by projecting the chemical reaction of light onto the painting (p. 36).

· Why did Van Gogh's [Sunflowers] turn brown and wither?

The part that chemically explains why Van Gogh's [Sunflowers] change color from yellow to brown is also interesting.

Dutch and Belgian scientists have been observing [Sunflowers], which is on display at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, for several years.

As a result, we confirmed that the yellow petals and stems in the picture were turning olive brown.

Scientists have speculated that the cause of the discoloration is that Van Gogh mixed chrome yellow with sulfate white to obtain a bright yellow color when he painted this painting.

It is said that Van Gogh used a large amount of yellow paint containing chromium.

Van Gogh enjoyed using yellow paints, and among them he used chrome yellow a lot.

Chrome yellow is produced by dissolving lead in nitric acid or acetic acid and adding a sodium dichromate (or sodium) solution to form a precipitate.

If an additive such as lead sulfate is added to this reaction or the pH is changed, a color ranging from light yellow to reddish brown is produced.

Chrome Yellow was cheap and was favored by poor artists like Van Gogh.

However, because it contains lead, when it comes into contact with sulfur contained in air pollution, it becomes lead sulfide (PbS), which is black.

Ultimately, as we entered the modern industrial society, the concern about discoloration inevitably grew (p. 298), and Van Gogh's [Sunflowers] were no exception.

· The lines of mathematics or the colors of chemistry? The battle between lines and colors.

Going a step further from the classic debate in art history called the 'battle of lines and colors,' the diagram that derives mathematics from lines and chemistry from colors is also quite refreshing (p. 177).

According to the theory of the superiority of the first and second colors from Poussin to Ingres, painting cannot create any form without drawing.

On the other hand, color is nothing more than an accident that changes with light.

The perfect balance and harmony that Renaissance artists sought to achieve was achieved through lines.

Without lines, we would not be able to devise perspective, symmetry, or ideal human proportions, all of which are based on mathematical thinking and principles.

The counterarguments from the color supremacists, centered around Rubens and Delacroix, are also not insignificant.

There is no such thing as a line; it is merely the boundary where the colored planes meet.

If lines are reason, color is emotion, but art cannot be established with reason alone, which lacks emotion.

Also, the nature and changes of color can be explained through chemistry, because the main material of painting, paint, is a chemical substance (p. 176).

· Chemical episodes about the colors and paints favored by artists

This book, in particular, focuses more heavily on the chemical episodes surrounding the unique colors and paints favored by each artist than the previous volume.

Spain's national painter Goya is famous for his black paintings.

Around 1820, Goya purchased a two-story mansion in the outskirts of Madrid, painted all the walls black, and created a series of 14 paintings, which people called 'Las Pinturas Negras' (Black Paintings) (p. 190).

Goya painted black paintings to convey a contemptuous message of protest against a world polluted by absurdity, but black was not a color that painters were particularly fond of.

As the Impressionist painters explored light, they realized that there was no light that corresponded to black, and so they removed black paint from their palettes.

In this way, black has the property of absorbing all light rather than reflecting it.

However, a completely dark color that absorbs all light does not exist as a substance.

Because completely absorbing light means an infinite space or black hole where no light is reflected (p. 192).

In addition, there are abundant stories of chemistry in painters and their works, such as Dutch portrait painter Frans Hals (page 100), who used orange to highlight the bright smile of the model in his portraits; Rococo painter Fragonard (page 154), who depicted scenes of adultery in a secret and erotic way using the complementary colors of green and pink; British landscape painter John Constable (page 208), who dedicated his life to painting more natural colors than the actual scenery; and Watteau (page 144), who damaged the preservation of his paintings by adding too much oil to his paints to achieve delicate and soft brushstrokes.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: May 27, 2019

- Page count, weight, size: 370 pages | 650g | 153*210*30mm

- ISBN13: 9791187150565

- ISBN10: 1187150568

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)