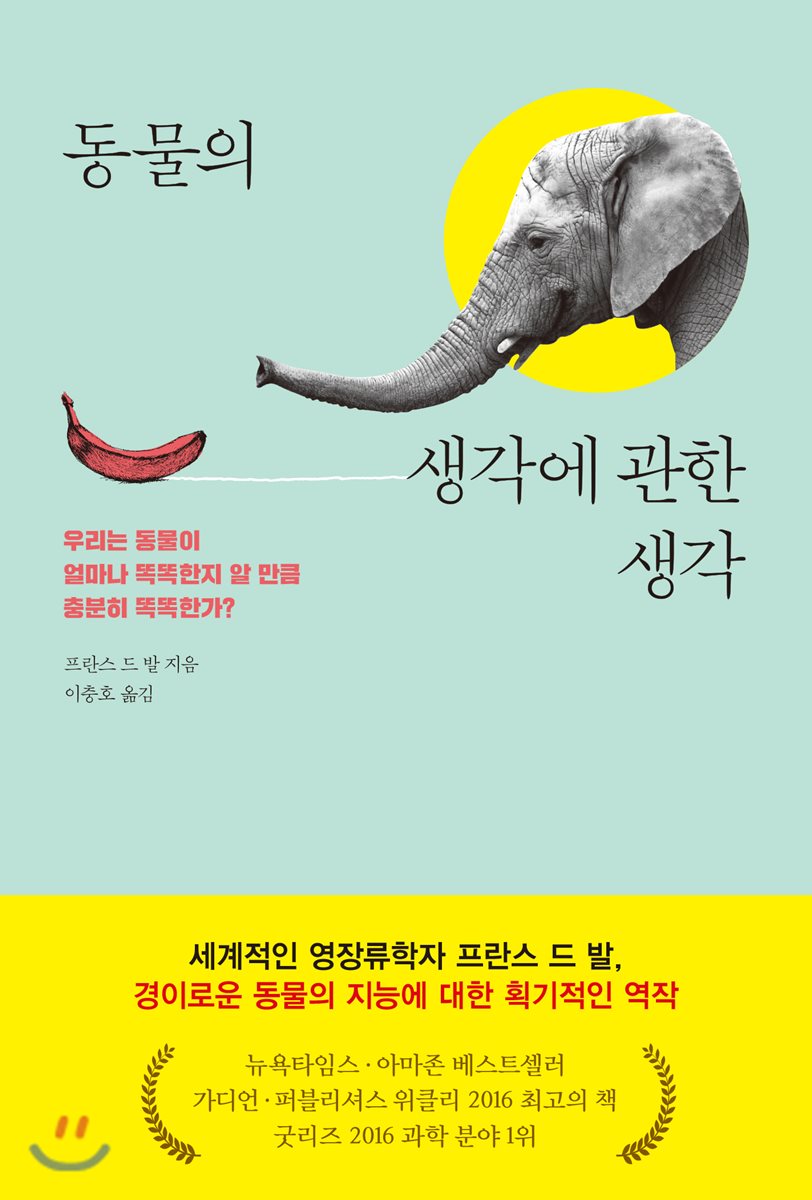

Thoughts on Animal Thoughts

|

Description

Book Introduction

Frans de Waal, a world-renowned primatologist,

A groundbreaking work on the intelligence of amazing animals

Are we smart enough to know how smart animals are? "Thoughts, Fast Facts, and Thoughts" is a groundbreaking work by world-renowned primatologist Frans de Waal, exploring the remarkable intelligence of animals.

It is a New York Times and Amazon bestseller and was named one of Publisher's Weekly's Best Books of 2016.

The Guardian's Best Book of 2016, Library Journal's Best Book of 2016.

It won first place in the Goodreads 2016 science category.

A fascinating journey of discovery into the intelligent world of animals

Despite the avalanche of discoveries in recent decades about the sophisticated cognition of animals, human attitudes toward animals have not changed much since the days of Aristotle, who believed that animals exist for the sake of humans.

After Darwin announced the theory of evolution, humans tried to protect their pride by listing all the things they could do that animals could not, but as animal research progressed, this began to take its toll.

The terms "instrumental man (Homo faber)" and "political man (Homo politicus)" became meaningless when chimpanzees, whose genes are 98.8% identical to humans, were discovered to have the ability to use tools and engage in political behavior, and high intelligence was no longer a sanctuary when scientists announced that dolphins possessed intelligence on a level equal to that of humans.

In response, humans ranked abilities.

They began to emphasize that there is a fundamental qualitative difference between animal and human intelligence, and from this perspective, except for animals that we generally think of as intelligent, such as chimpanzees, elephants, and crows, the rest of the animals are still lower creatures without emotions or thoughts.

World-renowned primatologist Frans de Waal has launched a full-scale revolt against this human-centered paradigm.

Decades of studying animals have given him a firm belief in animal intelligence and emotions, while also leading him to question the uniqueness of humans.

He discovered that animals are not only much smarter than we imagine, but that humans may not even be superior to animals.

He also argues that there is no reason to consider any one ability more special than another, since the minds and thoughts of all animals have developed in a way that is helpful to their survival.

In Thinking, Fast and Slow, de Waal shows how evolutionary cognition, the field that studies cognition from an evolutionary perspective, has grown dramatically over the past two decades.

This book is a journey that explores the intellectual world of animals and dismantles human strongholds one by one. Through fascinating research and moving stories, the author reveals that values once considered human, such as cooperation, humor, justice, altruism, rationality, intention, and emotion, can also be found in animals.

From rats regretting their decisions to octopuses that recognize human faces to chimpanzees whose extraordinary memories flattened our noses, there are no longer any off-limits zones for animals.

Covering a wide range of species, including primates, octopuses, wasps, dolphins, crows, and porpoises, he creates engaging and witty accounts of animals using their intelligence on a daily basis.

After reading this book, you will not only see animals differently, but you will also think a lot about human arrogance and humility.

A groundbreaking work on the intelligence of amazing animals

Are we smart enough to know how smart animals are? "Thoughts, Fast Facts, and Thoughts" is a groundbreaking work by world-renowned primatologist Frans de Waal, exploring the remarkable intelligence of animals.

It is a New York Times and Amazon bestseller and was named one of Publisher's Weekly's Best Books of 2016.

The Guardian's Best Book of 2016, Library Journal's Best Book of 2016.

It won first place in the Goodreads 2016 science category.

A fascinating journey of discovery into the intelligent world of animals

Despite the avalanche of discoveries in recent decades about the sophisticated cognition of animals, human attitudes toward animals have not changed much since the days of Aristotle, who believed that animals exist for the sake of humans.

After Darwin announced the theory of evolution, humans tried to protect their pride by listing all the things they could do that animals could not, but as animal research progressed, this began to take its toll.

The terms "instrumental man (Homo faber)" and "political man (Homo politicus)" became meaningless when chimpanzees, whose genes are 98.8% identical to humans, were discovered to have the ability to use tools and engage in political behavior, and high intelligence was no longer a sanctuary when scientists announced that dolphins possessed intelligence on a level equal to that of humans.

In response, humans ranked abilities.

They began to emphasize that there is a fundamental qualitative difference between animal and human intelligence, and from this perspective, except for animals that we generally think of as intelligent, such as chimpanzees, elephants, and crows, the rest of the animals are still lower creatures without emotions or thoughts.

World-renowned primatologist Frans de Waal has launched a full-scale revolt against this human-centered paradigm.

Decades of studying animals have given him a firm belief in animal intelligence and emotions, while also leading him to question the uniqueness of humans.

He discovered that animals are not only much smarter than we imagine, but that humans may not even be superior to animals.

He also argues that there is no reason to consider any one ability more special than another, since the minds and thoughts of all animals have developed in a way that is helpful to their survival.

In Thinking, Fast and Slow, de Waal shows how evolutionary cognition, the field that studies cognition from an evolutionary perspective, has grown dramatically over the past two decades.

This book is a journey that explores the intellectual world of animals and dismantles human strongholds one by one. Through fascinating research and moving stories, the author reveals that values once considered human, such as cooperation, humor, justice, altruism, rationality, intention, and emotion, can also be found in animals.

From rats regretting their decisions to octopuses that recognize human faces to chimpanzees whose extraordinary memories flattened our noses, there are no longer any off-limits zones for animals.

Covering a wide range of species, including primates, octopuses, wasps, dolphins, crows, and porpoises, he creates engaging and witty accounts of animals using their intelligence on a daily basis.

After reading this book, you will not only see animals differently, but you will also think a lot about human arrogance and humility.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

prolog

Chapter 1 The Magic Well

If I were a bug | Like a blind man touching an elephant | I oppose anthropomorphism.

Chapter 2: A Tale of Two Schools

Do Dogs Want to Want? | The Hunger Games | Why Simple Explanations Matter | Clever Hans's Amazing Deception | Primatology at the Desk | Thawing | The Bee-Eater

Chapter 3 Cognitive Waves

Eureka! | The Face of the Wasp | Redefining Humanity | Crows Use Tools Too!

Chapter 4: Speak Up

Alex the Genius Parrot | The Language of Confusing Animals | For Dogs

Chapter 5: The Measure of All Things

Evolution Stops in the Human Mind | Guessing Other People's Minds | The Clever Hans Effect in Children | The Transmission of Habits | Pause

Chapter 6 Social Skills

Machiavellian Intelligence | Animals That Know Triangulation | Experiments You Can Only Know by Trying Them | Fish Cooperate | Elephant Politics

Chapter 7: Only Time Will Tell

In Search of Lost Time | Why Don't Cats Carry Umbrellas? | Animal Willpower | Know What You Know | Consciousness

Chapter 8: The Mirror and the Bottle

The Sound-Sensitive Elephant | The Magpie in the Mirror | The Mollusk Mind | When in Rome | What's in a Name?

Chapter 9 Evolutionary Cognition

Acknowledgements

Glossary of Terms

main

References

Search

Chapter 1 The Magic Well

If I were a bug | Like a blind man touching an elephant | I oppose anthropomorphism.

Chapter 2: A Tale of Two Schools

Do Dogs Want to Want? | The Hunger Games | Why Simple Explanations Matter | Clever Hans's Amazing Deception | Primatology at the Desk | Thawing | The Bee-Eater

Chapter 3 Cognitive Waves

Eureka! | The Face of the Wasp | Redefining Humanity | Crows Use Tools Too!

Chapter 4: Speak Up

Alex the Genius Parrot | The Language of Confusing Animals | For Dogs

Chapter 5: The Measure of All Things

Evolution Stops in the Human Mind | Guessing Other People's Minds | The Clever Hans Effect in Children | The Transmission of Habits | Pause

Chapter 6 Social Skills

Machiavellian Intelligence | Animals That Know Triangulation | Experiments You Can Only Know by Trying Them | Fish Cooperate | Elephant Politics

Chapter 7: Only Time Will Tell

In Search of Lost Time | Why Don't Cats Carry Umbrellas? | Animal Willpower | Know What You Know | Consciousness

Chapter 8: The Mirror and the Bottle

The Sound-Sensitive Elephant | The Magpie in the Mirror | The Mollusk Mind | When in Rome | What's in a Name?

Chapter 9 Evolutionary Cognition

Acknowledgements

Glossary of Terms

main

References

Search

Into the book

For a long time, scientists believed that elephants could not use tools.

This pachyderm failed the task in the same banana test as above, as it did not use the stick.

The elephant's failure was not due to its inability to pick up objects from a flat surface.

Because elephants live close to the ground and are always picking up things (sometimes very small things).

The researchers concluded that the elephants simply didn't understand the problem.

No one ever thought that researchers didn't understand elephants.

― From Chapter 1, ‘The Magic Well’

I find the term inhuman very offensive.

Because we lump together millions of species for the lack of certain attributes, we treat them all as if they are all lacking something.

Poor things, their name is inhuman! When students use this term in their writing, I can't help but quip in a sarcastic comment, and to be fair, I add in the margin that the animals in question are not only inhuman, but also inhuman penguins, hyenas, and so on.

― From Chapter 1, ‘The Magic Well’

The wasps live in small groups and have clearly defined castes, so it is advantageous to identify each individual in the group.

The black and yellow markings on their faces help a lot in distinguishing them from each other.

A species of wasp closely related to the wasp has a less specialized social life and lacks facial recognition abilities.

This shows how much cognition depends on ecological conditions.

― In Chapter 3, ‘Cognitive Waves’

As for arguments emphasizing the neural connections in the brain, I wonder how we can explain animals with brains larger than our 1.35kg brains.

Dolphins have brains weighing 1.5 kg, elephants 4 kg, and sperm whales 8 kg. How can we explain the consciousness of these animals? Do they perhaps possess even more consciousness than we do? Or does consciousness depend on the number of neurons? The picture is somewhat unclear on this point.

For a long time, it was thought that our brains had more neurons than any other animal on Earth, regardless of brain size, but now it has been discovered that elephant brains have three times as many neurons as ours—257 billion to be exact.

― From Chapter 5, ‘The Measure of All Things’

It goes without saying that what science is really trying to understand is not the rat liver or the human liver, but the liver itself.

All organs and processes are much older than our own species, and have undergone some unique modifications over millions of years of evolution.

Evolution always works this way.

But why should cognition be any different? Our first task is to understand how cognition generally works, what elements are necessary for its proper functioning, and how these elements fit together with the sensory systems and ecology of a species.

― From Chapter 5, ‘The Measure of All Things’

The recent reputation of chimpanzees as violent and belligerent (even 'demonic') is based almost entirely on observations of how they treat members of neighboring groups in the wild.

In the wild, chimpanzees sometimes engage in brutal attacks over territory.

Fatal fights are so rare that it took decades for scientists to agree that they actually happen, but this fact has left chimpanzees with a deeply ingrained image.

The average rate of deaths from fighting in any outdoor setting is about once every seven years.

Moreover, this behavior does not appear to be a characteristic that distinguishes chimpanzees from us.

So why is it that while our species' intergroup warfare is properly viewed as a large-scale collective effort, this behavior is cited as evidence to deny the cooperative nature of chimpanzees? The same logic should apply to chimpanzees.

― In Chapter 6, ‘Social Skills’

Octopuses have about 2,000 suckers, each of which has a ganglion containing about 500,000 nerve cells.

So, in addition to the 65 million neurons in the brain, there are a lot of extra neurons.

In addition, ganglia are lined up in chains along the legs.

The brain connects all of these 'mini brains' and these mini brains are also connected to each other.

Instead of having a central command center like ours, the cephalopod nervous system is more like the Internet.

Local command posts are spread out over a wide area.

The severed leg wiggles around on its own and even picks up food.

Similarly, shrimp or small crabs can be moved towards the mouth, passing them from one sucker to the next, as if on a conveyor belt.

All of this may sound a bit far-fetched.

An animal with skin that sees ahead and eight arms that each think independently! ― Chapter 8, "The Mirror and the Bottle"

This pachyderm failed the task in the same banana test as above, as it did not use the stick.

The elephant's failure was not due to its inability to pick up objects from a flat surface.

Because elephants live close to the ground and are always picking up things (sometimes very small things).

The researchers concluded that the elephants simply didn't understand the problem.

No one ever thought that researchers didn't understand elephants.

― From Chapter 1, ‘The Magic Well’

I find the term inhuman very offensive.

Because we lump together millions of species for the lack of certain attributes, we treat them all as if they are all lacking something.

Poor things, their name is inhuman! When students use this term in their writing, I can't help but quip in a sarcastic comment, and to be fair, I add in the margin that the animals in question are not only inhuman, but also inhuman penguins, hyenas, and so on.

― From Chapter 1, ‘The Magic Well’

The wasps live in small groups and have clearly defined castes, so it is advantageous to identify each individual in the group.

The black and yellow markings on their faces help a lot in distinguishing them from each other.

A species of wasp closely related to the wasp has a less specialized social life and lacks facial recognition abilities.

This shows how much cognition depends on ecological conditions.

― In Chapter 3, ‘Cognitive Waves’

As for arguments emphasizing the neural connections in the brain, I wonder how we can explain animals with brains larger than our 1.35kg brains.

Dolphins have brains weighing 1.5 kg, elephants 4 kg, and sperm whales 8 kg. How can we explain the consciousness of these animals? Do they perhaps possess even more consciousness than we do? Or does consciousness depend on the number of neurons? The picture is somewhat unclear on this point.

For a long time, it was thought that our brains had more neurons than any other animal on Earth, regardless of brain size, but now it has been discovered that elephant brains have three times as many neurons as ours—257 billion to be exact.

― From Chapter 5, ‘The Measure of All Things’

It goes without saying that what science is really trying to understand is not the rat liver or the human liver, but the liver itself.

All organs and processes are much older than our own species, and have undergone some unique modifications over millions of years of evolution.

Evolution always works this way.

But why should cognition be any different? Our first task is to understand how cognition generally works, what elements are necessary for its proper functioning, and how these elements fit together with the sensory systems and ecology of a species.

― From Chapter 5, ‘The Measure of All Things’

The recent reputation of chimpanzees as violent and belligerent (even 'demonic') is based almost entirely on observations of how they treat members of neighboring groups in the wild.

In the wild, chimpanzees sometimes engage in brutal attacks over territory.

Fatal fights are so rare that it took decades for scientists to agree that they actually happen, but this fact has left chimpanzees with a deeply ingrained image.

The average rate of deaths from fighting in any outdoor setting is about once every seven years.

Moreover, this behavior does not appear to be a characteristic that distinguishes chimpanzees from us.

So why is it that while our species' intergroup warfare is properly viewed as a large-scale collective effort, this behavior is cited as evidence to deny the cooperative nature of chimpanzees? The same logic should apply to chimpanzees.

― In Chapter 6, ‘Social Skills’

Octopuses have about 2,000 suckers, each of which has a ganglion containing about 500,000 nerve cells.

So, in addition to the 65 million neurons in the brain, there are a lot of extra neurons.

In addition, ganglia are lined up in chains along the legs.

The brain connects all of these 'mini brains' and these mini brains are also connected to each other.

Instead of having a central command center like ours, the cephalopod nervous system is more like the Internet.

Local command posts are spread out over a wide area.

The severed leg wiggles around on its own and even picks up food.

Similarly, shrimp or small crabs can be moved towards the mouth, passing them from one sucker to the next, as if on a conveyor belt.

All of this may sound a bit far-fetched.

An animal with skin that sees ahead and eight arms that each think independently! ― Chapter 8, "The Mirror and the Bottle"

--- From the text

Publisher's Review

Are humans the only species that are rational, considerate of others, enjoy humor, and imagine the future?

Chimpanzees, crows, and octopuses do it too!

Can humans understand animals? This is a crucial question for researchers who observe animals, including those concerned with animal rights, well-being, and freedom.

Frans de Waal takes this question one step further.

“Are we smart enough to know how smart animals are?” He believes that one of the biggest obstacles to understanding animals is anthropocentric thinking, and through this book’s central question, he points out that it is not that animals lack abilities, but rather that we are not properly understanding animals.

Humans have never been lions or dolphins, and have never communicated with them, so it is difficult for us to demonstrate the mental level of animals or to imagine a world where animals live in completely different environments.

For example, some animals perceive the world in different ways, such as by perceiving ultraviolet light while others live in a world of smells.

Even if they live in the same oak tree, some animals perch on its branches, others live under the bark, and foxes dig burrows between the roots to make their nests. Each animal perceives the same tree differently.

In order to properly read the minds of animals living in such a different world, it is necessary to first understand the world in their own way.

It would be unfair to ask a squirrel, which doesn't need computational skills, to count to ten, just as humans don't need ultrasound to navigate in the dark.

The more we look at the world through animal eyes rather than human standards, the more we encounter the mysterious and wondrous abilities of animals, and de Waal vividly introduces us to the fascinating world of these animals.

It's well known that chimpanzees and humans share similar behaviors, but a closer look at aspects of social life, such as family love and power struggles, reveals a surprising degree of similarity.

Just as wearing a baseball cap backwards is fashionable, so too is sticking grass stalks in one's ears a popular activity among chimpanzee groups.

It is not at all unreasonable to substitute the political behavior of chimpanzees for human history.

An old male chimpanzee who was dethroned a year ago acts as the power behind the scenes for a while after a successful coup by supporting an ambitious young male who is trying to take over the dominant position, and a male who has a rival in a fight for the position will groom his friends to secure support in advance.

When the pups' play turns into a fight, the mothers, who have been watching each other closely, approach the matriarch chimpanzee and ask for mediation.

Some people counter that chimpanzees are an exception, as they are humans' closest living relatives.

To such people, De Waal supports the general intelligence of animals by citing the intelligent behavior of various animals as evidence.

Even animals that humans never thought of, such as octopuses, moray eels, and wasps, are setting foot in places that were once thought to be human territory.

They show signs of being self-aware, forming culture, imagining the future, recognizing faces, and so on.

The mirror test, often considered an important benchmark for self-awareness, was long passed only by humans and great apes, but recently dolphins, elephants, and magpies have also passed it, joining the ranks of animals with self-awareness.

The reason this test is noteworthy is that recognizing one's own reflection in the mirror means understanding oneself as an individual separate from others.

Parrots are often dismissed as mere imitators, but the unfair stigma of being "bird-brained" has been dispelled with the appearance of Alex, a genius parrot who can accurately distinguish objects and do addition.

The idea that only humans have names was changed by dolphins.

Each dolphin has its own unique whistle that can be called its own name, and sometimes they mimic the whistle of another dolphin to call out the name of their companion.

Clark's pine crows are experts at retrieving pine nuts hidden in hundreds of locations, numbering over 20,000, and chimpanzees can remember more than five numbers they have seen in the blink of an eye (0.2 seconds).

It is a level that humans cannot keep up with even with training.

Empathy is a crucial skill that binds society together, and it requires being able to accurately understand the other person's situation and what they want in order to help them.

There was a case where a dolphin fainted in the ocean, and two dolphins supported the fainted whale from both sides to help it breathe.

While you are helping like this, your breathing hole will be submerged in water and you will not be able to breathe.

Even a sea bream can guess other people's minds.

A magpie that hides food while another bird is watching moves the food to another place as soon as the other bird leaves.

An interesting fact is that only birds that have ever stolen another bird's food will hide their own food again.

It is suspecting others of their crimes based on one's own crimes.

De Waal says that many animals have cognitive abilities in common, and that apes stand out because of their high intelligence, but that if it's an ability necessary for survival, that cognitive ability can be found in any animal, including dogs, birds, reptiles, and fish.

If humans and animals perform the same actions, there is no reason to treat their intentions differently.

In a herd of elephants, the behavior of lower-ranking elephants showing obedience to the leader elephant is no different from the behavior of a subordinate kissing the leader's ring.

It is reasonable to assume that a bonobo walking a long distance to carry a heavy stone has a clear purpose.

It's like seeing a man carrying a ladder and assuming he wouldn't be carrying it for no reason.

If bipedalism is an important indicator for humans, then bipedalism in chickens, kangaroos, and bonobos should also be objectively evaluated.

De Waal is wary not only of our colored glasses, but also of the objectivity of scientific theories and experiments.

According to him, the mirror test, which verifies self-awareness, is just one of many methods for studying the self.

The reason the mirror test cannot be an absolute standard is that some animals are better suited to tactile tests than visual conditions, and some monkeys do not scratch their heads or look inside their mouths when looking in a mirror, but do not confuse their reflections with those of other animals.

The relationship between brain size and intelligence is also something to reconsider.

Social and technical intelligence are difficult to distinguish, and elephants and whales have much larger brains than humans.

The same goes for assessing intelligence using neurons.

It has been discovered that elephant brains have three times as many neurons as humans, making it difficult to argue for human uniqueness based solely on the brain.

Throughout the book, de Waal discusses individual cases, arguing that the important question is not finding similarities and differences between animals and humans.

Each species has its own way of life, which determines what it needs to know to survive.

His insight that all cognitive abilities are special, specialized for their environment, forces us to rethink all our thinking about humans and animals.

Chimpanzees, crows, and octopuses do it too!

Can humans understand animals? This is a crucial question for researchers who observe animals, including those concerned with animal rights, well-being, and freedom.

Frans de Waal takes this question one step further.

“Are we smart enough to know how smart animals are?” He believes that one of the biggest obstacles to understanding animals is anthropocentric thinking, and through this book’s central question, he points out that it is not that animals lack abilities, but rather that we are not properly understanding animals.

Humans have never been lions or dolphins, and have never communicated with them, so it is difficult for us to demonstrate the mental level of animals or to imagine a world where animals live in completely different environments.

For example, some animals perceive the world in different ways, such as by perceiving ultraviolet light while others live in a world of smells.

Even if they live in the same oak tree, some animals perch on its branches, others live under the bark, and foxes dig burrows between the roots to make their nests. Each animal perceives the same tree differently.

In order to properly read the minds of animals living in such a different world, it is necessary to first understand the world in their own way.

It would be unfair to ask a squirrel, which doesn't need computational skills, to count to ten, just as humans don't need ultrasound to navigate in the dark.

The more we look at the world through animal eyes rather than human standards, the more we encounter the mysterious and wondrous abilities of animals, and de Waal vividly introduces us to the fascinating world of these animals.

It's well known that chimpanzees and humans share similar behaviors, but a closer look at aspects of social life, such as family love and power struggles, reveals a surprising degree of similarity.

Just as wearing a baseball cap backwards is fashionable, so too is sticking grass stalks in one's ears a popular activity among chimpanzee groups.

It is not at all unreasonable to substitute the political behavior of chimpanzees for human history.

An old male chimpanzee who was dethroned a year ago acts as the power behind the scenes for a while after a successful coup by supporting an ambitious young male who is trying to take over the dominant position, and a male who has a rival in a fight for the position will groom his friends to secure support in advance.

When the pups' play turns into a fight, the mothers, who have been watching each other closely, approach the matriarch chimpanzee and ask for mediation.

Some people counter that chimpanzees are an exception, as they are humans' closest living relatives.

To such people, De Waal supports the general intelligence of animals by citing the intelligent behavior of various animals as evidence.

Even animals that humans never thought of, such as octopuses, moray eels, and wasps, are setting foot in places that were once thought to be human territory.

They show signs of being self-aware, forming culture, imagining the future, recognizing faces, and so on.

The mirror test, often considered an important benchmark for self-awareness, was long passed only by humans and great apes, but recently dolphins, elephants, and magpies have also passed it, joining the ranks of animals with self-awareness.

The reason this test is noteworthy is that recognizing one's own reflection in the mirror means understanding oneself as an individual separate from others.

Parrots are often dismissed as mere imitators, but the unfair stigma of being "bird-brained" has been dispelled with the appearance of Alex, a genius parrot who can accurately distinguish objects and do addition.

The idea that only humans have names was changed by dolphins.

Each dolphin has its own unique whistle that can be called its own name, and sometimes they mimic the whistle of another dolphin to call out the name of their companion.

Clark's pine crows are experts at retrieving pine nuts hidden in hundreds of locations, numbering over 20,000, and chimpanzees can remember more than five numbers they have seen in the blink of an eye (0.2 seconds).

It is a level that humans cannot keep up with even with training.

Empathy is a crucial skill that binds society together, and it requires being able to accurately understand the other person's situation and what they want in order to help them.

There was a case where a dolphin fainted in the ocean, and two dolphins supported the fainted whale from both sides to help it breathe.

While you are helping like this, your breathing hole will be submerged in water and you will not be able to breathe.

Even a sea bream can guess other people's minds.

A magpie that hides food while another bird is watching moves the food to another place as soon as the other bird leaves.

An interesting fact is that only birds that have ever stolen another bird's food will hide their own food again.

It is suspecting others of their crimes based on one's own crimes.

De Waal says that many animals have cognitive abilities in common, and that apes stand out because of their high intelligence, but that if it's an ability necessary for survival, that cognitive ability can be found in any animal, including dogs, birds, reptiles, and fish.

If humans and animals perform the same actions, there is no reason to treat their intentions differently.

In a herd of elephants, the behavior of lower-ranking elephants showing obedience to the leader elephant is no different from the behavior of a subordinate kissing the leader's ring.

It is reasonable to assume that a bonobo walking a long distance to carry a heavy stone has a clear purpose.

It's like seeing a man carrying a ladder and assuming he wouldn't be carrying it for no reason.

If bipedalism is an important indicator for humans, then bipedalism in chickens, kangaroos, and bonobos should also be objectively evaluated.

De Waal is wary not only of our colored glasses, but also of the objectivity of scientific theories and experiments.

According to him, the mirror test, which verifies self-awareness, is just one of many methods for studying the self.

The reason the mirror test cannot be an absolute standard is that some animals are better suited to tactile tests than visual conditions, and some monkeys do not scratch their heads or look inside their mouths when looking in a mirror, but do not confuse their reflections with those of other animals.

The relationship between brain size and intelligence is also something to reconsider.

Social and technical intelligence are difficult to distinguish, and elephants and whales have much larger brains than humans.

The same goes for assessing intelligence using neurons.

It has been discovered that elephant brains have three times as many neurons as humans, making it difficult to argue for human uniqueness based solely on the brain.

Throughout the book, de Waal discusses individual cases, arguing that the important question is not finding similarities and differences between animals and humans.

Each species has its own way of life, which determines what it needs to know to survive.

His insight that all cognitive abilities are special, specialized for their environment, forces us to rethink all our thinking about humans and animals.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: July 25, 2017

- Page count, weight, size: 488 pages | 670g | 145*215*30mm

- ISBN13: 9788984076334

- ISBN10: 8984076333

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)