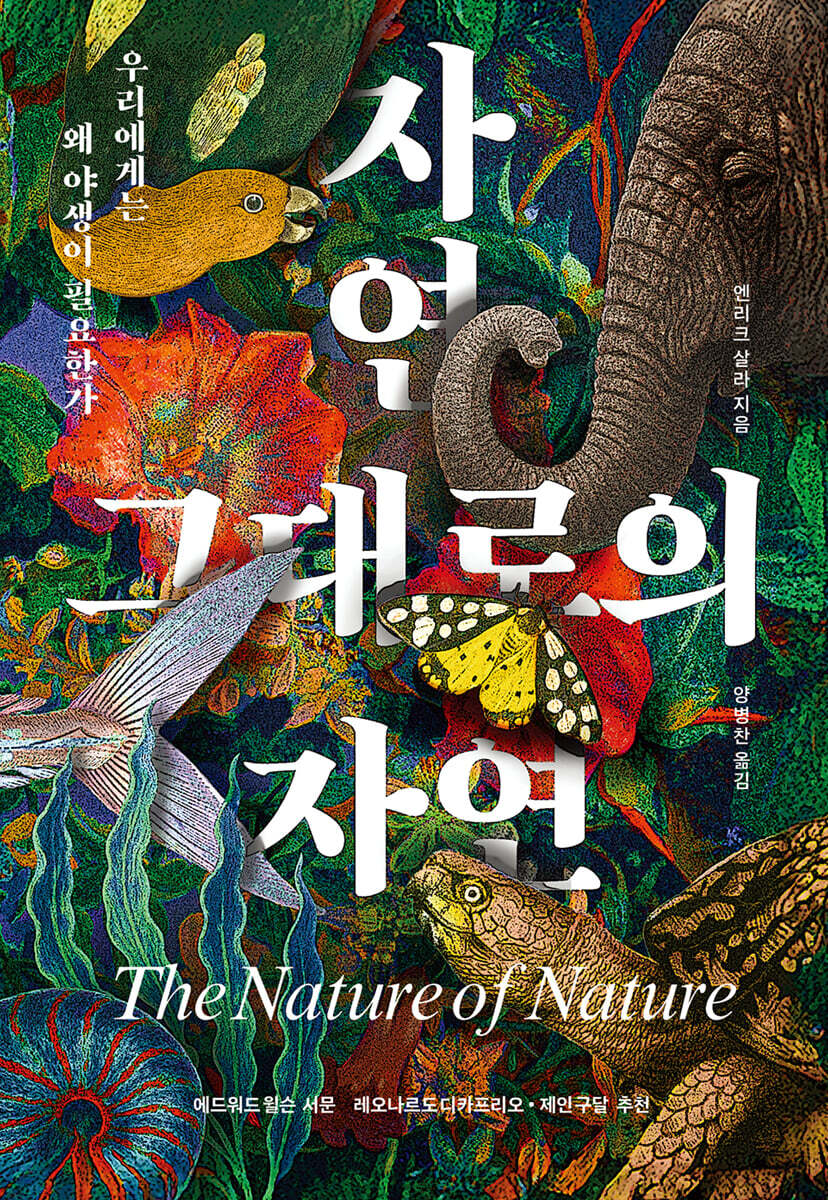

Nature as it is

|

Description

Book Introduction

How does nature work?

How Humans Are Changing Nature

What are the socio-economic benefits of biodiversity?

Enrique Sala, a world-renowned marine ecologist and environmental activist, highlights the many reasons why preserving Earth's biodiversity makes logical, emotional, and economic sense.

All living things play important roles in the intertwined biosphere.

According to Sala, the natural world is a perfect circular economy, where every living thing supports every other living thing, both when alive and when dead.

He also makes a compelling case for the practical value of wilderness conservation.

Explaining the economic benefits of establishing wildlife sanctuaries on land and no-take zones at sea.

This book, which explores the moral imperative of protecting nature and its economic benefits, will completely change the way we think about the world and our future.

How Humans Are Changing Nature

What are the socio-economic benefits of biodiversity?

Enrique Sala, a world-renowned marine ecologist and environmental activist, highlights the many reasons why preserving Earth's biodiversity makes logical, emotional, and economic sense.

All living things play important roles in the intertwined biosphere.

According to Sala, the natural world is a perfect circular economy, where every living thing supports every other living thing, both when alive and when dead.

He also makes a compelling case for the practical value of wilderness conservation.

Explaining the economic benefits of establishing wildlife sanctuaries on land and no-take zones at sea.

This book, which explores the moral imperative of protecting nature and its economic benefits, will completely change the way we think about the world and our future.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Foreword by Edward Wilson

1.

Reproduction of nature

2.

What is an ecosystem?

3.

the smallest ecosystem

4.

ecological transition

5.

ecosystem boundaries

6.

Are all species equal?

7.

biosphere

8.

How are we different?

9.

The Benefits of Diversity

10.

protected area

11.

Rewilding

12.

moral obligation

13.

The Economics of Nature

14.

Why We Need Wilderness

Conclusion: The Nature of the Coronavirus

Acknowledgements | References | Copyright and Sources of Illustrations in the Pictorial | Search | Pictorial

1.

Reproduction of nature

2.

What is an ecosystem?

3.

the smallest ecosystem

4.

ecological transition

5.

ecosystem boundaries

6.

Are all species equal?

7.

biosphere

8.

How are we different?

9.

The Benefits of Diversity

10.

protected area

11.

Rewilding

12.

moral obligation

13.

The Economics of Nature

14.

Why We Need Wilderness

Conclusion: The Nature of the Coronavirus

Acknowledgements | References | Copyright and Sources of Illustrations in the Pictorial | Search | Pictorial

Detailed image

Into the book

There is not much light under the dense forest canopy, so most plants cannot thrive.

However, their seeds can survive underground for decades.

For example, in some areas of Chile's Atacama Desert, it never rains—at least not once in a human lifetime.

Therefore, a desert is a dry area with no noticeable life.

But in 2018, rain fell in areas that hadn't rained in 100 years.

Then, a few days later, the barren yellow surface of the desert transformed into a carpet of colorful wildflowers.

These flowers multiplied and produced seeds that fell onto the desert floor, where they withered and shriveled after the miraculous rains had worn off.

The new seeds, covered in dust and sand, will wait impatiently to regain their 15-day glory, which may take another century.

Nature is slow, but it always gets the job done.

--- p.47

Humans create asymmetrical boundaries across the planet.

Consider, for example, the rich tropical forests of Borneo, a mature ecosystem that supports the world's most diverse species.

Humans have cleared the forests and converted them into oil palm plantations, monocultures with virtually no diversity.

The only place less ecologically mature than a monoculture farm is a scorched forest.

Oil palm will be consumed as food in cities around the world, but humans will give nothing back to the ecosystem in return.

As long as humans maintain farms, the habitat will never regain its former ecological glory, and the asymmetrical boundary between forest and farm will persist.

--- p.64

The "tiny ecological heroes" like bacteria and fungi in the soil help trees grow, and the trees form forests that attract rain, which influences weather patterns around the world and erodes the highest peaks of continents, and the silica is absorbed by microscopic ocean algae that, millions of years later, creates sand in what will become deserts, which in turn helps feed the tiny life forms in the forest soil.

At this point, Gaia might actually exist.

--- p.97

Our analysis found that restoring biodiversity within marine protected areas also helped improve surrounding fisheries.

Fishermen around the study area caught on average four times as many fish with the same amount of effort as before.

Tourism revenues in protected areas have also increased significantly, as divers (who want to see fish-filled waters rather than empty oceans) flock to marine reserves.

We concluded that:

Recovering lost biodiversity is possible, and such recovery is likely to lead to increased productivity and stability.

Additionally, increased fish catches around protected areas and non-extractive revenues (e.g. tourism revenue) from protected areas can also be expected.

--- p.125~126

According to a recently published report, 73 percent of the land has been altered or degraded by humans.

Forests are so fragmented that if we were to parachute into any random spot in any forest in the world, there would be a 70 percent chance that we would be within a kilometer of the forest edge.

Only 27 percent of our planet's remaining terrestrial ecosystems remain intact, which is not enough to prevent mass extinction. According to the UN, up to one million species are expected to become extinct in the coming decades, and terrestrial vertebrate species have declined by 60 percent since 1970.

If current trends continue, we will not be able to prevent the global collapse of bird and insect populations, we will not have enough plants to absorb excess carbon dioxide, and we will not be able to mitigate the effects of climate change.

We must not only preserve what we have – intact forests, grasslands, peatlands, wetlands, and other natural ecosystems – but also upgrade them.

--- p.143

Awe and wonder make people fall in love with nature and begin to care for it in ways they never thought possible before.

Only after providing key decision makers with a unique experience can we present scientific research and economic analyses that justify nature conservation.

Ultimately, what these leaders need are facts that demonstrate that conservation has more benefits than the status quo and convince the Treasury or the Secretary of Oceans and Fisheries that it makes sense to protect parts of the ocean.

But love and attraction always come first.

Leaders who are in love with nature intuitively feel a responsibility to protect it and understand that it is their moral duty.

--- p.171~172

Economists use the concept of net present value (NPV)—the present value of all future cash flows generated by a project.

That is, considering the investment risk, it is assumed that “if you invest $1 received today, you can receive interest,” so the NPV of “$1 received now” must be higher than the NPV of “$1 to be received in a few years.”

The NPV of a shrimp farm in southern Thailand's five-year operating income is about $8,000 per hectare, but when the resulting water pollution costs are taken into account, the total is only $200.

In contrast, the net present value (NPV) of one hectare of intact mangrove forest in Thailand is $194,000, thanks to a range of ecosystem services including carbon sequestration, erosion control, storm protection, food production, and recreational use.

Therefore, protecting mangroves while simultaneously restoring lost ones can create much greater economic value than converting them into shrimp farms.

--- p.178

Why doesn't the world feel the same tragic loss for a natural cathedral? We, myself included, were deeply shocked by the fire at Notre Dame Cathedral because no one could have predicted the loss of such a historic icon.

Notre Dame Cathedral, the Eiffel Tower, Big Ben, and the ruins of the Parthenon are representative examples, and these symbols are part of an unchanging cultural landscape.

We all expect them to be there.

But when these icons are put in danger, most people realize that they are more than just stones and trees.

These places are part of our identity as a civilization, world-class tourist destinations and sacred places of devotion for many.

But if the natural world, often called "Mother Nature," is part of our identity, a revered destination, a sacred place, shouldn't it be treated with the same respect when it's in danger?

However, their seeds can survive underground for decades.

For example, in some areas of Chile's Atacama Desert, it never rains—at least not once in a human lifetime.

Therefore, a desert is a dry area with no noticeable life.

But in 2018, rain fell in areas that hadn't rained in 100 years.

Then, a few days later, the barren yellow surface of the desert transformed into a carpet of colorful wildflowers.

These flowers multiplied and produced seeds that fell onto the desert floor, where they withered and shriveled after the miraculous rains had worn off.

The new seeds, covered in dust and sand, will wait impatiently to regain their 15-day glory, which may take another century.

Nature is slow, but it always gets the job done.

--- p.47

Humans create asymmetrical boundaries across the planet.

Consider, for example, the rich tropical forests of Borneo, a mature ecosystem that supports the world's most diverse species.

Humans have cleared the forests and converted them into oil palm plantations, monocultures with virtually no diversity.

The only place less ecologically mature than a monoculture farm is a scorched forest.

Oil palm will be consumed as food in cities around the world, but humans will give nothing back to the ecosystem in return.

As long as humans maintain farms, the habitat will never regain its former ecological glory, and the asymmetrical boundary between forest and farm will persist.

--- p.64

The "tiny ecological heroes" like bacteria and fungi in the soil help trees grow, and the trees form forests that attract rain, which influences weather patterns around the world and erodes the highest peaks of continents, and the silica is absorbed by microscopic ocean algae that, millions of years later, creates sand in what will become deserts, which in turn helps feed the tiny life forms in the forest soil.

At this point, Gaia might actually exist.

--- p.97

Our analysis found that restoring biodiversity within marine protected areas also helped improve surrounding fisheries.

Fishermen around the study area caught on average four times as many fish with the same amount of effort as before.

Tourism revenues in protected areas have also increased significantly, as divers (who want to see fish-filled waters rather than empty oceans) flock to marine reserves.

We concluded that:

Recovering lost biodiversity is possible, and such recovery is likely to lead to increased productivity and stability.

Additionally, increased fish catches around protected areas and non-extractive revenues (e.g. tourism revenue) from protected areas can also be expected.

--- p.125~126

According to a recently published report, 73 percent of the land has been altered or degraded by humans.

Forests are so fragmented that if we were to parachute into any random spot in any forest in the world, there would be a 70 percent chance that we would be within a kilometer of the forest edge.

Only 27 percent of our planet's remaining terrestrial ecosystems remain intact, which is not enough to prevent mass extinction. According to the UN, up to one million species are expected to become extinct in the coming decades, and terrestrial vertebrate species have declined by 60 percent since 1970.

If current trends continue, we will not be able to prevent the global collapse of bird and insect populations, we will not have enough plants to absorb excess carbon dioxide, and we will not be able to mitigate the effects of climate change.

We must not only preserve what we have – intact forests, grasslands, peatlands, wetlands, and other natural ecosystems – but also upgrade them.

--- p.143

Awe and wonder make people fall in love with nature and begin to care for it in ways they never thought possible before.

Only after providing key decision makers with a unique experience can we present scientific research and economic analyses that justify nature conservation.

Ultimately, what these leaders need are facts that demonstrate that conservation has more benefits than the status quo and convince the Treasury or the Secretary of Oceans and Fisheries that it makes sense to protect parts of the ocean.

But love and attraction always come first.

Leaders who are in love with nature intuitively feel a responsibility to protect it and understand that it is their moral duty.

--- p.171~172

Economists use the concept of net present value (NPV)—the present value of all future cash flows generated by a project.

That is, considering the investment risk, it is assumed that “if you invest $1 received today, you can receive interest,” so the NPV of “$1 received now” must be higher than the NPV of “$1 to be received in a few years.”

The NPV of a shrimp farm in southern Thailand's five-year operating income is about $8,000 per hectare, but when the resulting water pollution costs are taken into account, the total is only $200.

In contrast, the net present value (NPV) of one hectare of intact mangrove forest in Thailand is $194,000, thanks to a range of ecosystem services including carbon sequestration, erosion control, storm protection, food production, and recreational use.

Therefore, protecting mangroves while simultaneously restoring lost ones can create much greater economic value than converting them into shrimp farms.

--- p.178

Why doesn't the world feel the same tragic loss for a natural cathedral? We, myself included, were deeply shocked by the fire at Notre Dame Cathedral because no one could have predicted the loss of such a historic icon.

Notre Dame Cathedral, the Eiffel Tower, Big Ben, and the ruins of the Parthenon are representative examples, and these symbols are part of an unchanging cultural landscape.

We all expect them to be there.

But when these icons are put in danger, most people realize that they are more than just stones and trees.

These places are part of our identity as a civilization, world-class tourist destinations and sacred places of devotion for many.

But if the natural world, often called "Mother Nature," is part of our identity, a revered destination, a sacred place, shouldn't it be treated with the same respect when it's in danger?

--- p.190~191

Publisher's Review

A love letter to all life on Earth!

Appealing to global participation in ecosystem conservation

A masterpiece by National Geographic's resident explorer, Enrique Sala.

Edward Wilson, Jane Goodall, King Charles III of England,

Recommended by Leonardo DiCaprio, James Cameron, and others

The Korean edition of Enrique Sala's "Nature as It Is," a book that fundamentally re-examines the relationship between humans and nature, has been published.

Blending scientific insights from a marine ecologist with field experience as an explorer, this book offers a multifaceted look at how we should view nature and why the wild is essential to humanity's future.

This book has garnered worldwide attention, receiving praise from legendary biologists such as Jane Goodall and Edward Wilson, as well as prominent cultural figures with environmental activism such as Leonardo DiCaprio and James Cameron, and global leaders such as King Charles III of England and Klaus Schwab, founder of the World Economic Forum.

"Nature as It Is" begins by introducing the 1991 Biosphere 2 experiment.

This project, which attempted to recreate a self-sufficient ecosystem to determine whether human colonies on other planets were possible, ultimately failed due to oxygen shortages, species extinction, and a collapsed food web.

The author notes that this failure paradoxically illustrates how complex and intricately the Earth's biosphere functions.

He emphasizes that no matter how advanced science and technology humans utilize, it is difficult to reproduce the complexity and sophistication of the Earth's ecosystem, and that we must recognize that the Earth exists in a miraculous balance and that we humans live within it, as part of it.

What is an ecosystem and how does it work?

This book begins by introducing the definition of an ecosystem and how it works, and then dives into the real story.

Ecosystems are not limited to forests or rivers.

It is a system in which living organisms and their physical environment interact and operate autonomously.

Cities can also be viewed as ecosystems intertwined with diverse organisms and infrastructure, demonstrating that the concept of defining an ecosystem is not fixed but can be applied flexibly.

The operating principles of ecosystems, such as food webs, energy flow, and self-regulation, are common to all biospheres.

The author introduces a microbial experiment to explain the basic principles of the ecosystem.

In the first half of the 20th century, biologist Franzese Gauze demonstrated resource competition, predation and prey, and the conditions for coexistence through experiments with yeast and paramecium worms in small test tubes.

The principle of competitive exclusion, which states that species competing for the same resources will eventually exclude one another, and the fact that predators and prey can coexist only through spatial shelter or migration from outside, provide important implications for understanding the basic mechanisms of natural ecosystems.

Ecological transitions, keystone species, humans, and biodiversity

The author then explains the concepts of “ecological transition” and “keystone species.”

Ecological succession refers to the process by which species composition and communities gradually change after a disturbance and move toward a new equilibrium.

This shift, where early species disappear and later species take hold, symbolizes the resilience and adaptability of ecosystems, and is observed in diverse environments such as forests, grasslands, and oceans.

In this process, there are entities whose numbers, at least, influence the structure and function of the entire ecosystem.

It is the “key species.”

These top predators and habitat builders influence the entire food web.

Humans, in particular, are a “superkeystone species” capable of designing, reorganizing, and massively transforming the very structure of the ecosystem.

Human activities such as agriculture, industry, and urbanization affect the entire natural world.

Therefore, the author emphasizes that the powerful influence of humans must be accompanied by moral responsibility, and that an ethical shift is needed to recognize that we are not consumers of nature, but merely a part of it.

In addition, the importance of “biodiversity” is confirmed.

Biodiversity increases the stability and resilience of ecosystems.

The more species there are, the more resilient the ecosystem can be to external shocks.

While single-crop agriculture is vulnerable to pests and diseases and climate change, environments with diverse species are highly resilient.

Biodiversity directly and indirectly contributes to human food, medicine, and emotional well-being.

Practical Solutions and the Economics of Nature

The book now moves towards practical solutions for ecosystem conservation and biodiversity preservation.

These are “designation of protected areas” and “rewilding.”

Simply designating a protected area is not enough; complete protection and systematic management are necessary to achieve real results.

Marine protected areas, in particular, show dramatic biomass recovery only in areas where fishing is completely prohibited.

This requires not only scientific research and monitoring, but also collaboration with local communities and policy will.

Meanwhile, rewilding is a strategy to restore damaged nature.

It is not simply a matter of restoring species, but a process of helping ecosystems regain their autonomy and function.

The experiment of reintroducing wolves to Yellowstone National Park in the United States in the 1990s went beyond controlling deer populations, and helped restore the ecosystem and move it to a more mature stage.

In this way, ecosystems operate through complex interactions, and humans can play a vital role in their recovery process.

The author also emphasizes that these efforts, thankfully, return to us as benefits.

In marine protected areas, fish populations increase rapidly within a few years after a fishing ban is implemented, and catches in adjacent waters also increase, increasing the income of local fishermen.

Additionally, wetlands and mangrove forests prevent floods and tsunamis and perform purification functions, reducing damage at a much lower cost than artificial disaster prevention infrastructure.

Tropical rainforests and coastal ecosystems absorb carbon, reducing the costs of climate change response.

This is worth trillions of dollars economically, and ultimately, ecosystem conservation is a very effective investment in the long run.

Protecting nature is not just a moral responsibility or environmental ideal; it is also an economically sound choice.

Why We Need Wilderness

Of course, the reason for preserving nature is not only because of practicality.

Life is inherently dignified, and humans have a moral responsibility to respect other living beings.

We must recognize all life in nature as beings with inherent value.

Ultimately, the core of this book lies in the answer to the question, “Why do we need wilderness?”

The wild is the foundation of human survival and a psychological and emotional refuge, and only when we live in harmony with nature can we truly thrive.

The author states that the COVID-19 pandemic that recently struck humanity is a disaster brought about by the destruction of nature, warning that there is no future without restoring a harmonious relationship between humans and nature.

Meanwhile, the efforts of translator Yang Byeong-chan, who was in charge of translating 『Nature as It Is』, further increased the value of the book.

Having won the 2019 Korean Publishing Culture Award for Translation, he contributes to enriching readers' reading experience with his appropriate and active translation in this book.

Accurate translations, easy-to-understand sentences, and rich, helpful translator's notes enhance the readability of this book.

He is quietly contributing to the Korean natural science community by translating medical and life science articles from overseas scientific journals such as Nature and Science and introducing them on social media every day.

Finally, the 16-page illustrated book at the end of the book helps readers recall and understand the contents of the text.

In particular, the painting “The Invisible Network of the Forest,” which illustrates the process by which trees exchange nutritional and stress signals through the fungal network beneath the forest floor, is a standout among the 20 or so vivid and elegant images.

Appealing to global participation in ecosystem conservation

A masterpiece by National Geographic's resident explorer, Enrique Sala.

Edward Wilson, Jane Goodall, King Charles III of England,

Recommended by Leonardo DiCaprio, James Cameron, and others

The Korean edition of Enrique Sala's "Nature as It Is," a book that fundamentally re-examines the relationship between humans and nature, has been published.

Blending scientific insights from a marine ecologist with field experience as an explorer, this book offers a multifaceted look at how we should view nature and why the wild is essential to humanity's future.

This book has garnered worldwide attention, receiving praise from legendary biologists such as Jane Goodall and Edward Wilson, as well as prominent cultural figures with environmental activism such as Leonardo DiCaprio and James Cameron, and global leaders such as King Charles III of England and Klaus Schwab, founder of the World Economic Forum.

"Nature as It Is" begins by introducing the 1991 Biosphere 2 experiment.

This project, which attempted to recreate a self-sufficient ecosystem to determine whether human colonies on other planets were possible, ultimately failed due to oxygen shortages, species extinction, and a collapsed food web.

The author notes that this failure paradoxically illustrates how complex and intricately the Earth's biosphere functions.

He emphasizes that no matter how advanced science and technology humans utilize, it is difficult to reproduce the complexity and sophistication of the Earth's ecosystem, and that we must recognize that the Earth exists in a miraculous balance and that we humans live within it, as part of it.

What is an ecosystem and how does it work?

This book begins by introducing the definition of an ecosystem and how it works, and then dives into the real story.

Ecosystems are not limited to forests or rivers.

It is a system in which living organisms and their physical environment interact and operate autonomously.

Cities can also be viewed as ecosystems intertwined with diverse organisms and infrastructure, demonstrating that the concept of defining an ecosystem is not fixed but can be applied flexibly.

The operating principles of ecosystems, such as food webs, energy flow, and self-regulation, are common to all biospheres.

The author introduces a microbial experiment to explain the basic principles of the ecosystem.

In the first half of the 20th century, biologist Franzese Gauze demonstrated resource competition, predation and prey, and the conditions for coexistence through experiments with yeast and paramecium worms in small test tubes.

The principle of competitive exclusion, which states that species competing for the same resources will eventually exclude one another, and the fact that predators and prey can coexist only through spatial shelter or migration from outside, provide important implications for understanding the basic mechanisms of natural ecosystems.

Ecological transitions, keystone species, humans, and biodiversity

The author then explains the concepts of “ecological transition” and “keystone species.”

Ecological succession refers to the process by which species composition and communities gradually change after a disturbance and move toward a new equilibrium.

This shift, where early species disappear and later species take hold, symbolizes the resilience and adaptability of ecosystems, and is observed in diverse environments such as forests, grasslands, and oceans.

In this process, there are entities whose numbers, at least, influence the structure and function of the entire ecosystem.

It is the “key species.”

These top predators and habitat builders influence the entire food web.

Humans, in particular, are a “superkeystone species” capable of designing, reorganizing, and massively transforming the very structure of the ecosystem.

Human activities such as agriculture, industry, and urbanization affect the entire natural world.

Therefore, the author emphasizes that the powerful influence of humans must be accompanied by moral responsibility, and that an ethical shift is needed to recognize that we are not consumers of nature, but merely a part of it.

In addition, the importance of “biodiversity” is confirmed.

Biodiversity increases the stability and resilience of ecosystems.

The more species there are, the more resilient the ecosystem can be to external shocks.

While single-crop agriculture is vulnerable to pests and diseases and climate change, environments with diverse species are highly resilient.

Biodiversity directly and indirectly contributes to human food, medicine, and emotional well-being.

Practical Solutions and the Economics of Nature

The book now moves towards practical solutions for ecosystem conservation and biodiversity preservation.

These are “designation of protected areas” and “rewilding.”

Simply designating a protected area is not enough; complete protection and systematic management are necessary to achieve real results.

Marine protected areas, in particular, show dramatic biomass recovery only in areas where fishing is completely prohibited.

This requires not only scientific research and monitoring, but also collaboration with local communities and policy will.

Meanwhile, rewilding is a strategy to restore damaged nature.

It is not simply a matter of restoring species, but a process of helping ecosystems regain their autonomy and function.

The experiment of reintroducing wolves to Yellowstone National Park in the United States in the 1990s went beyond controlling deer populations, and helped restore the ecosystem and move it to a more mature stage.

In this way, ecosystems operate through complex interactions, and humans can play a vital role in their recovery process.

The author also emphasizes that these efforts, thankfully, return to us as benefits.

In marine protected areas, fish populations increase rapidly within a few years after a fishing ban is implemented, and catches in adjacent waters also increase, increasing the income of local fishermen.

Additionally, wetlands and mangrove forests prevent floods and tsunamis and perform purification functions, reducing damage at a much lower cost than artificial disaster prevention infrastructure.

Tropical rainforests and coastal ecosystems absorb carbon, reducing the costs of climate change response.

This is worth trillions of dollars economically, and ultimately, ecosystem conservation is a very effective investment in the long run.

Protecting nature is not just a moral responsibility or environmental ideal; it is also an economically sound choice.

Why We Need Wilderness

Of course, the reason for preserving nature is not only because of practicality.

Life is inherently dignified, and humans have a moral responsibility to respect other living beings.

We must recognize all life in nature as beings with inherent value.

Ultimately, the core of this book lies in the answer to the question, “Why do we need wilderness?”

The wild is the foundation of human survival and a psychological and emotional refuge, and only when we live in harmony with nature can we truly thrive.

The author states that the COVID-19 pandemic that recently struck humanity is a disaster brought about by the destruction of nature, warning that there is no future without restoring a harmonious relationship between humans and nature.

Meanwhile, the efforts of translator Yang Byeong-chan, who was in charge of translating 『Nature as It Is』, further increased the value of the book.

Having won the 2019 Korean Publishing Culture Award for Translation, he contributes to enriching readers' reading experience with his appropriate and active translation in this book.

Accurate translations, easy-to-understand sentences, and rich, helpful translator's notes enhance the readability of this book.

He is quietly contributing to the Korean natural science community by translating medical and life science articles from overseas scientific journals such as Nature and Science and introducing them on social media every day.

Finally, the 16-page illustrated book at the end of the book helps readers recall and understand the contents of the text.

In particular, the painting “The Invisible Network of the Forest,” which illustrates the process by which trees exchange nutritional and stress signals through the fungal network beneath the forest floor, is a standout among the 20 or so vivid and elegant images.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: June 10, 2025

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 264 pages | 558g | 162*232*21mm

- ISBN13: 9788932925202

- ISBN10: 8932925208

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)