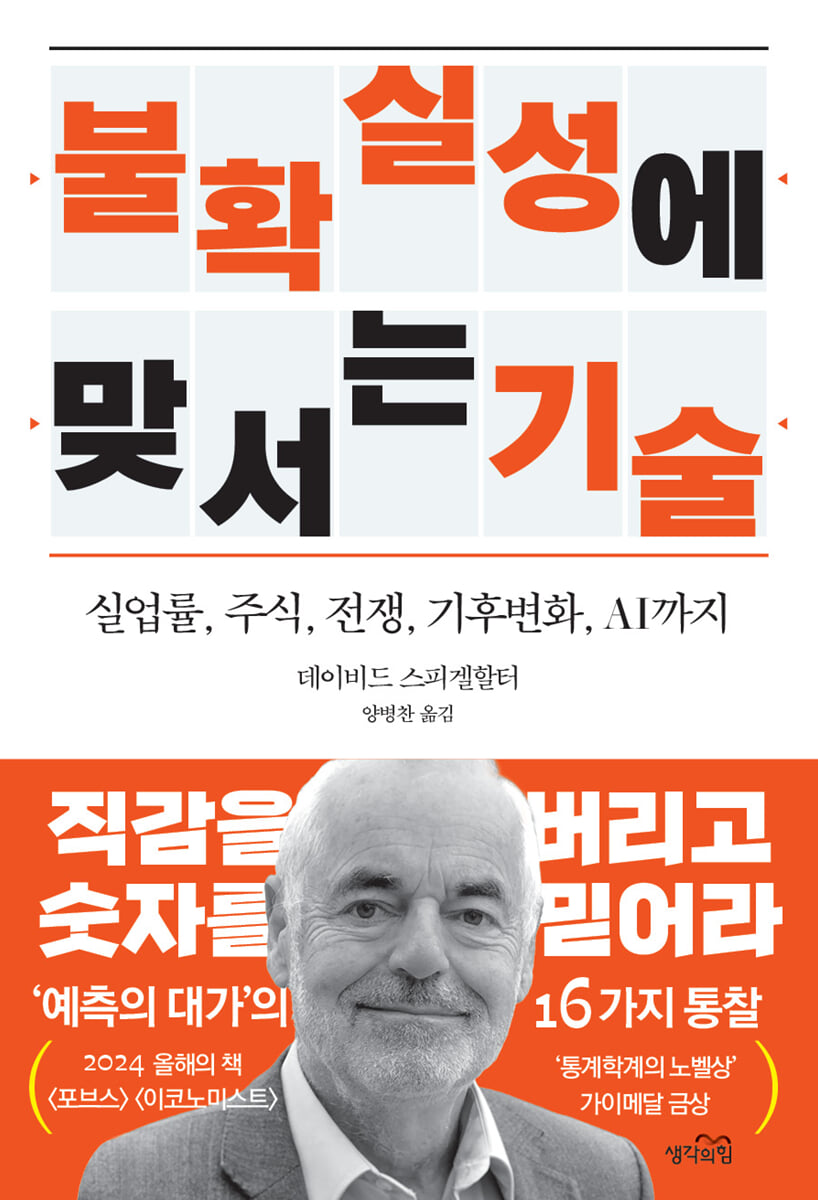

Technology to face uncertainty

|

Description

Book Introduction

“The value of good choices will become more expensive as time goes on.”

The easiest and most powerful technique to combat future uncertainty!

Future Survival Strategies from the "Master of Forecasting"

The world is full of uncertainty.

This includes things we don't know, things we can't control like chance or luck, events predicted by formulas and models but for which we have no idea how to prepare, and even unknowns like COVID-19 that we didn't even know existed.

The ignorance that arises in these situations leads to avoidance of reality and lazy choices, or to choices made out of fear and paralyzed reason.

But looking ahead doesn't always lead to great choices.

It was assumed that President Trump would raise tariffs if he were elected, but when that actually happened, the whole world panicked.

How can we survive in the fog without making bad moves? David Spiegelhalter, one of the world's leading statisticians, has been explaining how to analyze uncertainty and randomness with statistics, create patterns, and interpret them.

And in this book, "Technology for Dealing with Uncertainty," we go beyond understanding numbers and trends to delve into more fundamental content.

The author, who has dedicated over 50 years to statistics, offers wisdom for coping with uncertainties and uncontrollable variables that cannot be captured by formulas or models, managing risk, and making wiser choices at crossroads.

It contains knowledge accumulated through insight into the latest research in various fields such as history, philosophy, and medicine, as well as mathematical tools such as Bayesian theorem, chaos theory, and ensembles.

Readers will learn how to mathematically interpret the products of indolence, such as fate, chance, and luck, the skills to uncover the meanings cleverly hidden in probability, and the strength to survive without panic, no matter what the future holds.

Spiegelhalter's masterpiece, "The Art of Dealing with Uncertainty," which won the gold Guy Medal, the Nobel Prize of statistics, immediately rose to number one on Amazon upon its publication and was recommended as a book of the year by Malcolm Gladwell's NEXT BIG IDEA, creating a lot of buzz.

The easiest and most powerful technique to combat future uncertainty!

Future Survival Strategies from the "Master of Forecasting"

The world is full of uncertainty.

This includes things we don't know, things we can't control like chance or luck, events predicted by formulas and models but for which we have no idea how to prepare, and even unknowns like COVID-19 that we didn't even know existed.

The ignorance that arises in these situations leads to avoidance of reality and lazy choices, or to choices made out of fear and paralyzed reason.

But looking ahead doesn't always lead to great choices.

It was assumed that President Trump would raise tariffs if he were elected, but when that actually happened, the whole world panicked.

How can we survive in the fog without making bad moves? David Spiegelhalter, one of the world's leading statisticians, has been explaining how to analyze uncertainty and randomness with statistics, create patterns, and interpret them.

And in this book, "Technology for Dealing with Uncertainty," we go beyond understanding numbers and trends to delve into more fundamental content.

The author, who has dedicated over 50 years to statistics, offers wisdom for coping with uncertainties and uncontrollable variables that cannot be captured by formulas or models, managing risk, and making wiser choices at crossroads.

It contains knowledge accumulated through insight into the latest research in various fields such as history, philosophy, and medicine, as well as mathematical tools such as Bayesian theorem, chaos theory, and ensembles.

Readers will learn how to mathematically interpret the products of indolence, such as fate, chance, and luck, the skills to uncover the meanings cleverly hidden in probability, and the strength to survive without panic, no matter what the future holds.

Spiegelhalter's masterpiece, "The Art of Dealing with Uncertainty," which won the gold Guy Medal, the Nobel Prize of statistics, immediately rose to number one on Amazon upon its publication and was recommended as a book of the year by Malcolm Gladwell's NEXT BIG IDEA, creating a lot of buzz.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Praise poured in for this book

introduction.

Uncertainty is both a crisis and an opportunity.

Chapter 1.

Uncertainty is personal

Chapter 2.

Don't tell me, show me with numbers

Chapter 3.

Does probability even exist?

Chapter 4.

Can we control chance?

Chapter 5.

How much of life is determined by luck?

Chapter 6.

Don't be fooled into thinking you can predict

Chapter 7.

The power of Bayes' theorem to change future possibilities

Chapter 8.

How Science Deals with Uncertainty

Chapter 9.

How much can we trust the probabilities?

Chapter 10.

Climate Change: Who is responsible for the crime?

Chapter 11.

Still, the math you need to know the future

Chapter 12.

How to avoid being swept up in future disasters

Chapter 13.

We must acknowledge deep uncertainty.

Chapter 14.

Technology to prevent chaos in politics, society, and economy

Chapter 15.

How to manage risk and overcome uncertainty

Chapter 16.

Be humble, embrace, and enjoy uncertainty.

Acknowledgements

Glossary

main

List of pictures

Table of Contents

Search

introduction.

Uncertainty is both a crisis and an opportunity.

Chapter 1.

Uncertainty is personal

Chapter 2.

Don't tell me, show me with numbers

Chapter 3.

Does probability even exist?

Chapter 4.

Can we control chance?

Chapter 5.

How much of life is determined by luck?

Chapter 6.

Don't be fooled into thinking you can predict

Chapter 7.

The power of Bayes' theorem to change future possibilities

Chapter 8.

How Science Deals with Uncertainty

Chapter 9.

How much can we trust the probabilities?

Chapter 10.

Climate Change: Who is responsible for the crime?

Chapter 11.

Still, the math you need to know the future

Chapter 12.

How to avoid being swept up in future disasters

Chapter 13.

We must acknowledge deep uncertainty.

Chapter 14.

Technology to prevent chaos in politics, society, and economy

Chapter 15.

How to manage risk and overcome uncertainty

Chapter 16.

Be humble, embrace, and enjoy uncertainty.

Acknowledgements

Glossary

main

List of pictures

Table of Contents

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

1.

Simply put, uncertainty is a relationship between someone (including 'you') and the external world, and therefore depends on the subjective perspective and knowledge of the observer.

So whenever we face uncertainty—whether we're thinking about life, weighing people's opinions, or conducting scientific research—personal judgment plays a crucial role.

Again, attitudes toward uncertainty can vary greatly from person to person.

Some people find unpredictability fascinating, while others may experience chronic anxiety.

--- 「Introduction.

Uncertainty is both a crisis and an opportunity.

2.

Uncertainty: Conscious awareness of ignorance.

An important problem reflected in this definition (and as we will see in Chapter 3, there may be subatomic exceptions) is that we should think of uncertainty not as a property of the world, but as a relation to the world.

That is, as we saw in the coin toss, two individuals or groups may have different knowledge or perspectives, so even for the same thing, there may be different degrees of uncertainty—which is quite reasonable.

This important idea runs through the entire book.

--- 「Chapter 1.

Uncertainty is personal.

3.

According to Tetlock's interpretation, hedgehogs, like Marxists, Christians, and liberals, have one grand theory and make their predictions based on it, making confident arguments.

Foxes, on the other hand, are skeptical of grand theories, cautious in their predictions, and prepared to adjust their thinking when faced with new evidence.

Tetlock found that foxes were much better at predicting things than hedgehogs, and that hedgehogs were particularly vulnerable to predictions on topics they thought they knew a lot about because they were overconfident.

--- 「Chapter 2.

Don't tell me, show me with numbers."

4.

Assuming this exchangeability, it is mathematically equivalent to saying that “the events on each date behave as if they were independent, that there is a true underlying probability for each eruption, and that the uncertainty about that unknown probability is expressed by a subjective epistemic distribution.”

How beautifully De Finetti has demonstrated all this! It's not surprising, but rather beautiful.

Starting from purely subjective expressions of belief, we show that we should act as if events were driven by objective probabilities.

--- Chapter 3.

"Does probability even exist?"

5.

According to the law of truly large numbers, coincidences occur because there are countless opportunities, and so surprising things can happen surprisingly often.

One of the most common examples, also known as the 'paradox of probability', is that in a randomly selected group of 23 people, at least half of them will have at least one pair with the same birthday.

For example, in more than half of soccer matches, two of the 22 players and referees on the field share a birthday.

--- 「Chapter 4.

Can we control chance?

6.

After considering all the stories presented in this chapter, my personal feeling is that luck is not a mystical force.

True luck comes only once, at birth, and the problem after that is making the most of the hand you are given in the face of uncontrollable external events.

So, if we think of chance as an inevitable unpredictability, I agree with the idea that 'luck is chance taken personally.'

In other words, all 'luck' can be said to be a label that is later put on the past.

--- 「Chapter 5.

How much of life is determined by luck?

7.

I think the fundamental problem with humans is that they can't grasp the fact that "random doesn't mean regular."

A standard trick for testing this is to throw a handful of rice on a map in front of a group of people, suggesting that it represents a particular cluster.

When a researcher says, “This represents a cancer patient,” people will immediately start looking for reasons why there are so many cases in a particular area.

But whether it's a plane crash or a birthday, randomness is often clumpy.

It's a bit simplistic to say that accidents always happen in groups of three, but we can easily expect that to happen often just by chance alone.

--- Chapter 6.

Don't be fooled into thinking you can predict it.

8.

The stories presented so far have shown how Bayesian thinking can renew our beliefs based on multiple pieces of evidence.

So far I have confined my inquiry to the question of belief in propositions that are true or false.

But it's natural to extend this process to learning other important things that are currently unknown, such as the actual population of a country or the average effectiveness of a drug.

Although not the subject of this book, Bayesian thinking guides us to the concept of statistical inference, which is inseparable from discussions of uncertainty.

--- Chapter 7.

The Power of Bayes' Theorem to Transform Future Possibilities

9.

Of course, if we could directly and accurately observe things, whether quantities or facts, we could simply say that something happened without having to worry about uncertainty.

However, we rarely have the opportunity to do so, and must make observations directly or indirectly related to the subject of interest and then draw conclusions based on the evidence provided by those data.

And that data will show volatility, some of which is unexplained.

Statistical inference is the process of converting this variability into an uncertainty assessment of the object of interest.

--- Chapter 8.

How Science Deals with Uncertainty

10.

We must be wary of both those who make overly confident claims, on the one hand, and those who deliberately seek to mislead by exaggerating uncertainty, on the other.

We should expect trustworthy communication, and when we make claims, we should draw conclusions with humility and uncertainty, and express confidence and empathy.

But living with uncertainty doesn't mean we should be overly cautious. We need to be adaptable and resilient, taking risks without being reckless.

This is a personal lesson I've learned from nearly 50 years of studying probability, chance, risk, ignorance, and luck.

I hope this resonates deeply with readers.

Uncertainty is inevitable.

If so, we must embrace uncertainty, accept it humbly, and even try to enjoy it.

Simply put, uncertainty is a relationship between someone (including 'you') and the external world, and therefore depends on the subjective perspective and knowledge of the observer.

So whenever we face uncertainty—whether we're thinking about life, weighing people's opinions, or conducting scientific research—personal judgment plays a crucial role.

Again, attitudes toward uncertainty can vary greatly from person to person.

Some people find unpredictability fascinating, while others may experience chronic anxiety.

--- 「Introduction.

Uncertainty is both a crisis and an opportunity.

2.

Uncertainty: Conscious awareness of ignorance.

An important problem reflected in this definition (and as we will see in Chapter 3, there may be subatomic exceptions) is that we should think of uncertainty not as a property of the world, but as a relation to the world.

That is, as we saw in the coin toss, two individuals or groups may have different knowledge or perspectives, so even for the same thing, there may be different degrees of uncertainty—which is quite reasonable.

This important idea runs through the entire book.

--- 「Chapter 1.

Uncertainty is personal.

3.

According to Tetlock's interpretation, hedgehogs, like Marxists, Christians, and liberals, have one grand theory and make their predictions based on it, making confident arguments.

Foxes, on the other hand, are skeptical of grand theories, cautious in their predictions, and prepared to adjust their thinking when faced with new evidence.

Tetlock found that foxes were much better at predicting things than hedgehogs, and that hedgehogs were particularly vulnerable to predictions on topics they thought they knew a lot about because they were overconfident.

--- 「Chapter 2.

Don't tell me, show me with numbers."

4.

Assuming this exchangeability, it is mathematically equivalent to saying that “the events on each date behave as if they were independent, that there is a true underlying probability for each eruption, and that the uncertainty about that unknown probability is expressed by a subjective epistemic distribution.”

How beautifully De Finetti has demonstrated all this! It's not surprising, but rather beautiful.

Starting from purely subjective expressions of belief, we show that we should act as if events were driven by objective probabilities.

--- Chapter 3.

"Does probability even exist?"

5.

According to the law of truly large numbers, coincidences occur because there are countless opportunities, and so surprising things can happen surprisingly often.

One of the most common examples, also known as the 'paradox of probability', is that in a randomly selected group of 23 people, at least half of them will have at least one pair with the same birthday.

For example, in more than half of soccer matches, two of the 22 players and referees on the field share a birthday.

--- 「Chapter 4.

Can we control chance?

6.

After considering all the stories presented in this chapter, my personal feeling is that luck is not a mystical force.

True luck comes only once, at birth, and the problem after that is making the most of the hand you are given in the face of uncontrollable external events.

So, if we think of chance as an inevitable unpredictability, I agree with the idea that 'luck is chance taken personally.'

In other words, all 'luck' can be said to be a label that is later put on the past.

--- 「Chapter 5.

How much of life is determined by luck?

7.

I think the fundamental problem with humans is that they can't grasp the fact that "random doesn't mean regular."

A standard trick for testing this is to throw a handful of rice on a map in front of a group of people, suggesting that it represents a particular cluster.

When a researcher says, “This represents a cancer patient,” people will immediately start looking for reasons why there are so many cases in a particular area.

But whether it's a plane crash or a birthday, randomness is often clumpy.

It's a bit simplistic to say that accidents always happen in groups of three, but we can easily expect that to happen often just by chance alone.

--- Chapter 6.

Don't be fooled into thinking you can predict it.

8.

The stories presented so far have shown how Bayesian thinking can renew our beliefs based on multiple pieces of evidence.

So far I have confined my inquiry to the question of belief in propositions that are true or false.

But it's natural to extend this process to learning other important things that are currently unknown, such as the actual population of a country or the average effectiveness of a drug.

Although not the subject of this book, Bayesian thinking guides us to the concept of statistical inference, which is inseparable from discussions of uncertainty.

--- Chapter 7.

The Power of Bayes' Theorem to Transform Future Possibilities

9.

Of course, if we could directly and accurately observe things, whether quantities or facts, we could simply say that something happened without having to worry about uncertainty.

However, we rarely have the opportunity to do so, and must make observations directly or indirectly related to the subject of interest and then draw conclusions based on the evidence provided by those data.

And that data will show volatility, some of which is unexplained.

Statistical inference is the process of converting this variability into an uncertainty assessment of the object of interest.

--- Chapter 8.

How Science Deals with Uncertainty

10.

We must be wary of both those who make overly confident claims, on the one hand, and those who deliberately seek to mislead by exaggerating uncertainty, on the other.

We should expect trustworthy communication, and when we make claims, we should draw conclusions with humility and uncertainty, and express confidence and empathy.

But living with uncertainty doesn't mean we should be overly cautious. We need to be adaptable and resilient, taking risks without being reckless.

This is a personal lesson I've learned from nearly 50 years of studying probability, chance, risk, ignorance, and luck.

I hope this resonates deeply with readers.

Uncertainty is inevitable.

If so, we must embrace uncertainty, accept it humbly, and even try to enjoy it.

--- 「Chapter 16.

Be humble, embrace, and enjoy uncertainty.

Be humble, embrace, and enjoy uncertainty.

Publisher's Review

★#1 Bestseller on Amazon upon publication★

★NEXT BIG IDEA CLUB Must-Reads of the Year★

★Winner of the Gold Guy Medal, the Nobel Prize of Statistics★

"How to Read Changes Accurately and Win the Battle of Probabilities"

Make the best decisions without being swayed by superstition, speculation, or emotions.

- Why didn't the Fukushima nuclear power plant predict that a tsunami would come?

- Why did Obama say the odds of killing bin Laden were “50:50”?

- How do insurance companies secretly use probability to reduce claims?

- Why do researchers deliberately teach AI ignorance?

- Why don't politicians admit they're wrong?

“Probability is the greatest invention of mankind!”

Great human attempts to survive in the face of chance and variables

Until you are trained as a weapon without being swayed by uncertainty!

In this book, the author argues that probability is essential to our survival, and that being able to accurately predict it is an illusion.

His groundbreaking claims, which seem to completely betray our long-held belief in mathematics as a product of rationality and reason, are a wake-up call to rescue us from the dangers of blind faith in mathematics and to teach us a more important lesson.

The Bay of Pigs invasion, which almost changed America's fate and remained a failure, was a miscalculation that occurred because the success rate of "30%" was described as "adequate."

Many people consider a '98% survival rate' to be better than a '2% mortality rate', and sometimes they use probability as a tool to manipulate evidence to induce a guilty verdict.

The book is full of examples of how mathematics has been misused or led to wrong decisions due to human ignorance or inclination.

The author points out that the reasons for such unfortunate events are the arrogance of humans who do not admit that they do not know something, the misconception that mathematics can interpret everything, and the closed-minded attitude that does not acknowledge uncertainty.

To mitigate risk and survive, humanity has relied on oracles, wagered on gambling, and achieved mathematical inventions such as statistical models and formulas, as well as modern artificial intelligence, all of which have taken on incredible intellectual challenges.

To survive the dangers of ignorance, humanity has achieved progress in probability and statistics, but has also shown regression by refusing to acknowledge randomness and explore uncertainty.

The author focuses on this very point, teaching us how to deal with uncontrollable variables and coincidences that inevitably arise, no matter how much we try to manipulate the calculator (p. 463).

To this end, the author brings in the logic of philosophy from which mathematics was born.

Humans are the subject, uncertainty is the object, and how we react to probability depends on the choices of the human being as the subject. (p. 14) When we say that there is a 60% chance of rain, the difference between someone who prepares by carrying an umbrella and someone who suffers may be trivial.

But shouldn't this choice be even more serious when it comes to stock market fluctuations, drug side effects, international politics, and the changes brought about by AI?

Although the topic can be difficult, the author, a long-time public-favored statistical communicator, wittily explains it with his signature wit and uses everyday, relatable examples to make it easy to understand.

If you want to avoid being caught in the so-called "perfect storm," the unknown cause of a major disaster, this book will teach you how to read patterns and trends and respond safely.

“What do people who make good choices think?”

From how to make luck yours to mind control techniques,

How a statistician thinks about using probability as a cheat key to life

In 1914, Gavrilo Princip, who was ordered to assassinate a politician, failed to complete the mission and was returning when he accidentally encountered the politician's car on the wrong road and succeeded in killing him immediately.

Should we consider the shooting incident that sparked World War II a stroke of luck or a stroke of bad luck? Is Murphy's Law, which states that bad luck repeats itself, valid? Why do people ask AI for their daily fortunes? The author argues that a fundamental human problem stems from the inability to grasp the truth that "randomness means irregularity." He points out that the human psychology, which fears ignorance and seeks immediate relief, leads to a belief in luck.

The author also suffered when he was diagnosed with cancer, thinking it was a misfortune, but as a statistician, he accepted the fact that cancer occurs by chance and devoted himself to cancer treatment.

The author says, 'Luck is a coincidence that is accepted personally.'

Luck is a variable and ex post facto named entity.

Einstein said, “God doesn’t play dice,” but the author reserves judgment on whether luck is deterministic and talks about how to accept it.

Ironically, acknowledging this allows us to proactively increase the likelihood that events will turn in our favor, rather than hoping for a stroke of luck.

Mind control when misfortune strikes can also be approached mathematically.

The reason probability becomes a disaster is often because it fails to acknowledge the possibility of error and mistakes, or because its expressions are vague.

Before the US invasion of Cuba, staff reported that there was a “high probability” of success, but this actually meant a 30% chance of success, and the operation was a disaster.

The author says that because verbal expressions have different meanings for different people and reflect a psychology of avoidance, it is necessary to show them in numbers to reduce the possibility of misjudgment.

Statistician George Box warned against being so confident in models that he said, “All models are wrong, and only some are useful.” While models provide outputs such as estimates and confidence intervals, the underlying assumptions are often incorrect.

To be flexible and resilient when unexpected events arise, we must be humble before our models.

The more uncertainty we acknowledge, the more trust we build.

Media, institutions, and governments mistakenly believe that they must make confident statements to gain the trust of their audiences.

This is because they believe that repeating statements will lead to criticism and that ambiguous expressions will cause distrust.

However, when research findings reveal uncertainty and present a balanced presentation, trust increases.

“The human brain subconsciously knows the safe path!”

From humanity's survival instinct to how self-driving cars operate,

About the amazing ability to avoid risk with an innate probability model

There are three balls in each of Bag 1 and Bag 2, but only Bag 2 has two spotted balls.

If you randomly select a bag and draw a ball, and it's a spotted ball, which bag would you be more likely to choose, bag 1 or bag 2? Also, if you draw a ball from the same bag again, what's the probability of it being a spotted ball? Intuitively, we'd assume the probability of drawing a spotted ball from bag 2 is higher than the probability of drawing a spotted ball from bag 2.

Although this is an intuition, it is quite accurate, so if we plug in the formula and calculate it, we can see that the uncertainty about bag 2 gradually decreases and the accuracy increases.

It's a simple example, but it's the fundamental concept of Bayes' theorem: we can modify probabilities based on our intuition and experience.

The probability we predict before experiencing something is called the 'prior probability', and the probability we know after experiencing something is called the 'posterior probability'.

It remains to be seen how closely our brain's neural components are linked to Bayes' theorem, but the important thing is that we already have an internal model that allows us to perceive changes in the world, anticipate future possibilities, and take action.

Self-driving cars also use this Bayesian update algorithm to anticipate road congestion and obstacles and find the best route.

Bayesian theorem guides us to instinctively avoid risks and make wise decisions.

However, some people may find using the Bayesian theorem difficult because they are stuck in the stereotype that probability is objective and infallible.

As the author emphasizes in the introduction, we must approach probability with an open mind, recognizing that it can change at any time and being able to handle it flexibly.

If we can question the validity of our assumptions and accept that change is inevitable, the Bayesian theorem we are born with can become a powerful weapon.

“Seek adventure, but make sure you have insurance.”

The true power of probability comes not from prediction, but from preparation!

9 Skills to Survive Future Disasters

Since the global COVID-19 pandemic, interest in humanity's chances of surviving various threats, from war to climate change to AI counterattacks, has grown.

However, accurately assessing the future is becoming increasingly difficult, with the prediction of a 60% chance that a natural pandemic would kill more than one million people by 2100, as predicted at a conference in 2008, being brought forward without warning to 2019.

However, the author cautions against taking excessive measures by giving up on prediction and focusing on prevention.

Not only is it socially costly and confusing, but it can also have unexpected side effects, such as Germany's nuclear phase-out campaign, which reduced the threat of nuclear power plants but turned them into the main culprit of environmental pollution.

So how can we use statistics and probability to survive future disasters? The author suggests nine techniques:

1.

Complexity: Face the global interconnectedness of risk and prepare for the butterfly effect.

2.

Redundancy: Don't obsess over optimization.

There may always be waste involved.

3.

Humility: Don't boast that your predictions and preparations are perfect.

There are always exceptions.

4.

Robustness: Create a suitable model that is not shaken by variables.

5.

Resilience: Strive to recover quickly from any outcome.

6.

Reversibility: If you anticipate a catastrophic loss, try to prevent the worst.

7.

Adaptability: Be flexible and agile in responding to new challenges.

8.

Openness: Focus on communication and collaboration, and avoid being fixated on a single point of view.

9.

Balance: Consider all potential risks and benefits, including side effects from preventive measures.

This list is intended for use in organizations and governments, but many of it is relevant to the decisions we make every day.

It is important for everyone to be able to predict accurately, but also to be humble and acknowledge the possibility of model errors, and always prepare for exceptions.

We must protect ourselves from the worst that can happen, while also being able to take advantage of the opportunities we encounter everywhere.

As the author urges, we must "not be afraid of adventure, but must plan thoroughly in advance and secure safe supports and insurance" (p. 471).

《The Art of Facing Uncertainty》 is a valuable and special book that will be of interest to both mathematics enthusiasts and those unfamiliar with mathematics.

The questions of how to deal with chance, ignorance, and risk discussed in this book are ones we inevitably face in our lives.

It will instantly shatter the prejudice of those who only see mathematics in black and white logic.

- The Economist

This book explores the nebulous science of uncertainty and our struggle to understand it.

One of the author's most important lessons is that even in an uncertain world, we must not lose our own subjectivity or fall into nihilism.

- The Wall Street Journal

This is a wonderfully engaging book that explores the fascinating challenges humans have faced in measuring uncertainty.

I can recommend it with confidence.

- Publisher's Weekly

This book, a mathematical approach to uncertainty, harmoniously blends philosophy, statistics, and history, and is told with a thoughtful and humble attitude to the end.

- The Times

A must-read for anyone dealing with unpredictable risks, researchers seeking to accurately address uncertainty in experiments, and citizens skeptical of expert opinions and data.

- The Guardian

David Spiegelhalter, Britain's most renowned statistician, extends his perspective from trivial matters like the probability of pulling a pair of matching socks from a drawer to serious questions about cancer incidence.

It forces us to understand and ultimately embrace uncertainty.

- Financial Times

The great masters of statistics provide excellent guides for embracing uncertainty.

Scientists are often pressured to predict the future with certainty, but this book frees us all from that shackle by telling us to acknowledge the limits of our knowledge.

- 〈Nature〉

★NEXT BIG IDEA CLUB Must-Reads of the Year★

★Winner of the Gold Guy Medal, the Nobel Prize of Statistics★

"How to Read Changes Accurately and Win the Battle of Probabilities"

Make the best decisions without being swayed by superstition, speculation, or emotions.

- Why didn't the Fukushima nuclear power plant predict that a tsunami would come?

- Why did Obama say the odds of killing bin Laden were “50:50”?

- How do insurance companies secretly use probability to reduce claims?

- Why do researchers deliberately teach AI ignorance?

- Why don't politicians admit they're wrong?

“Probability is the greatest invention of mankind!”

Great human attempts to survive in the face of chance and variables

Until you are trained as a weapon without being swayed by uncertainty!

In this book, the author argues that probability is essential to our survival, and that being able to accurately predict it is an illusion.

His groundbreaking claims, which seem to completely betray our long-held belief in mathematics as a product of rationality and reason, are a wake-up call to rescue us from the dangers of blind faith in mathematics and to teach us a more important lesson.

The Bay of Pigs invasion, which almost changed America's fate and remained a failure, was a miscalculation that occurred because the success rate of "30%" was described as "adequate."

Many people consider a '98% survival rate' to be better than a '2% mortality rate', and sometimes they use probability as a tool to manipulate evidence to induce a guilty verdict.

The book is full of examples of how mathematics has been misused or led to wrong decisions due to human ignorance or inclination.

The author points out that the reasons for such unfortunate events are the arrogance of humans who do not admit that they do not know something, the misconception that mathematics can interpret everything, and the closed-minded attitude that does not acknowledge uncertainty.

To mitigate risk and survive, humanity has relied on oracles, wagered on gambling, and achieved mathematical inventions such as statistical models and formulas, as well as modern artificial intelligence, all of which have taken on incredible intellectual challenges.

To survive the dangers of ignorance, humanity has achieved progress in probability and statistics, but has also shown regression by refusing to acknowledge randomness and explore uncertainty.

The author focuses on this very point, teaching us how to deal with uncontrollable variables and coincidences that inevitably arise, no matter how much we try to manipulate the calculator (p. 463).

To this end, the author brings in the logic of philosophy from which mathematics was born.

Humans are the subject, uncertainty is the object, and how we react to probability depends on the choices of the human being as the subject. (p. 14) When we say that there is a 60% chance of rain, the difference between someone who prepares by carrying an umbrella and someone who suffers may be trivial.

But shouldn't this choice be even more serious when it comes to stock market fluctuations, drug side effects, international politics, and the changes brought about by AI?

Although the topic can be difficult, the author, a long-time public-favored statistical communicator, wittily explains it with his signature wit and uses everyday, relatable examples to make it easy to understand.

If you want to avoid being caught in the so-called "perfect storm," the unknown cause of a major disaster, this book will teach you how to read patterns and trends and respond safely.

“What do people who make good choices think?”

From how to make luck yours to mind control techniques,

How a statistician thinks about using probability as a cheat key to life

In 1914, Gavrilo Princip, who was ordered to assassinate a politician, failed to complete the mission and was returning when he accidentally encountered the politician's car on the wrong road and succeeded in killing him immediately.

Should we consider the shooting incident that sparked World War II a stroke of luck or a stroke of bad luck? Is Murphy's Law, which states that bad luck repeats itself, valid? Why do people ask AI for their daily fortunes? The author argues that a fundamental human problem stems from the inability to grasp the truth that "randomness means irregularity." He points out that the human psychology, which fears ignorance and seeks immediate relief, leads to a belief in luck.

The author also suffered when he was diagnosed with cancer, thinking it was a misfortune, but as a statistician, he accepted the fact that cancer occurs by chance and devoted himself to cancer treatment.

The author says, 'Luck is a coincidence that is accepted personally.'

Luck is a variable and ex post facto named entity.

Einstein said, “God doesn’t play dice,” but the author reserves judgment on whether luck is deterministic and talks about how to accept it.

Ironically, acknowledging this allows us to proactively increase the likelihood that events will turn in our favor, rather than hoping for a stroke of luck.

Mind control when misfortune strikes can also be approached mathematically.

The reason probability becomes a disaster is often because it fails to acknowledge the possibility of error and mistakes, or because its expressions are vague.

Before the US invasion of Cuba, staff reported that there was a “high probability” of success, but this actually meant a 30% chance of success, and the operation was a disaster.

The author says that because verbal expressions have different meanings for different people and reflect a psychology of avoidance, it is necessary to show them in numbers to reduce the possibility of misjudgment.

Statistician George Box warned against being so confident in models that he said, “All models are wrong, and only some are useful.” While models provide outputs such as estimates and confidence intervals, the underlying assumptions are often incorrect.

To be flexible and resilient when unexpected events arise, we must be humble before our models.

The more uncertainty we acknowledge, the more trust we build.

Media, institutions, and governments mistakenly believe that they must make confident statements to gain the trust of their audiences.

This is because they believe that repeating statements will lead to criticism and that ambiguous expressions will cause distrust.

However, when research findings reveal uncertainty and present a balanced presentation, trust increases.

“The human brain subconsciously knows the safe path!”

From humanity's survival instinct to how self-driving cars operate,

About the amazing ability to avoid risk with an innate probability model

There are three balls in each of Bag 1 and Bag 2, but only Bag 2 has two spotted balls.

If you randomly select a bag and draw a ball, and it's a spotted ball, which bag would you be more likely to choose, bag 1 or bag 2? Also, if you draw a ball from the same bag again, what's the probability of it being a spotted ball? Intuitively, we'd assume the probability of drawing a spotted ball from bag 2 is higher than the probability of drawing a spotted ball from bag 2.

Although this is an intuition, it is quite accurate, so if we plug in the formula and calculate it, we can see that the uncertainty about bag 2 gradually decreases and the accuracy increases.

It's a simple example, but it's the fundamental concept of Bayes' theorem: we can modify probabilities based on our intuition and experience.

The probability we predict before experiencing something is called the 'prior probability', and the probability we know after experiencing something is called the 'posterior probability'.

It remains to be seen how closely our brain's neural components are linked to Bayes' theorem, but the important thing is that we already have an internal model that allows us to perceive changes in the world, anticipate future possibilities, and take action.

Self-driving cars also use this Bayesian update algorithm to anticipate road congestion and obstacles and find the best route.

Bayesian theorem guides us to instinctively avoid risks and make wise decisions.

However, some people may find using the Bayesian theorem difficult because they are stuck in the stereotype that probability is objective and infallible.

As the author emphasizes in the introduction, we must approach probability with an open mind, recognizing that it can change at any time and being able to handle it flexibly.

If we can question the validity of our assumptions and accept that change is inevitable, the Bayesian theorem we are born with can become a powerful weapon.

“Seek adventure, but make sure you have insurance.”

The true power of probability comes not from prediction, but from preparation!

9 Skills to Survive Future Disasters

Since the global COVID-19 pandemic, interest in humanity's chances of surviving various threats, from war to climate change to AI counterattacks, has grown.

However, accurately assessing the future is becoming increasingly difficult, with the prediction of a 60% chance that a natural pandemic would kill more than one million people by 2100, as predicted at a conference in 2008, being brought forward without warning to 2019.

However, the author cautions against taking excessive measures by giving up on prediction and focusing on prevention.

Not only is it socially costly and confusing, but it can also have unexpected side effects, such as Germany's nuclear phase-out campaign, which reduced the threat of nuclear power plants but turned them into the main culprit of environmental pollution.

So how can we use statistics and probability to survive future disasters? The author suggests nine techniques:

1.

Complexity: Face the global interconnectedness of risk and prepare for the butterfly effect.

2.

Redundancy: Don't obsess over optimization.

There may always be waste involved.

3.

Humility: Don't boast that your predictions and preparations are perfect.

There are always exceptions.

4.

Robustness: Create a suitable model that is not shaken by variables.

5.

Resilience: Strive to recover quickly from any outcome.

6.

Reversibility: If you anticipate a catastrophic loss, try to prevent the worst.

7.

Adaptability: Be flexible and agile in responding to new challenges.

8.

Openness: Focus on communication and collaboration, and avoid being fixated on a single point of view.

9.

Balance: Consider all potential risks and benefits, including side effects from preventive measures.

This list is intended for use in organizations and governments, but many of it is relevant to the decisions we make every day.

It is important for everyone to be able to predict accurately, but also to be humble and acknowledge the possibility of model errors, and always prepare for exceptions.

We must protect ourselves from the worst that can happen, while also being able to take advantage of the opportunities we encounter everywhere.

As the author urges, we must "not be afraid of adventure, but must plan thoroughly in advance and secure safe supports and insurance" (p. 471).

《The Art of Facing Uncertainty》 is a valuable and special book that will be of interest to both mathematics enthusiasts and those unfamiliar with mathematics.

The questions of how to deal with chance, ignorance, and risk discussed in this book are ones we inevitably face in our lives.

It will instantly shatter the prejudice of those who only see mathematics in black and white logic.

- The Economist

This book explores the nebulous science of uncertainty and our struggle to understand it.

One of the author's most important lessons is that even in an uncertain world, we must not lose our own subjectivity or fall into nihilism.

- The Wall Street Journal

This is a wonderfully engaging book that explores the fascinating challenges humans have faced in measuring uncertainty.

I can recommend it with confidence.

- Publisher's Weekly

This book, a mathematical approach to uncertainty, harmoniously blends philosophy, statistics, and history, and is told with a thoughtful and humble attitude to the end.

- The Times

A must-read for anyone dealing with unpredictable risks, researchers seeking to accurately address uncertainty in experiments, and citizens skeptical of expert opinions and data.

- The Guardian

David Spiegelhalter, Britain's most renowned statistician, extends his perspective from trivial matters like the probability of pulling a pair of matching socks from a drawer to serious questions about cancer incidence.

It forces us to understand and ultimately embrace uncertainty.

- Financial Times

The great masters of statistics provide excellent guides for embracing uncertainty.

Scientists are often pressured to predict the future with certainty, but this book frees us all from that shackle by telling us to acknowledge the limits of our knowledge.

- 〈Nature〉

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: May 30, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 520 pages | 784g | 152*223*35mm

- ISBN13: 9791193166994

- ISBN10: 1193166993

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)