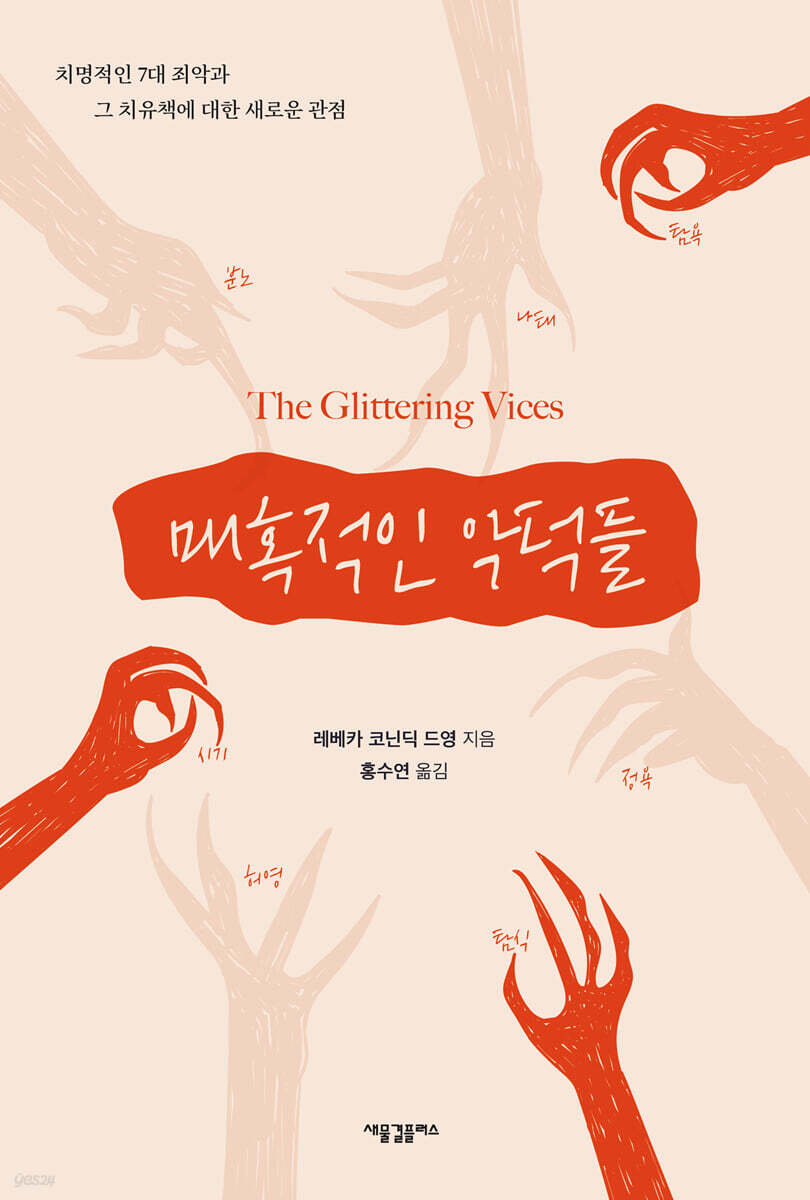

Fascinating villains

|

Description

Book Introduction

Today, the vices traditionally known as the Seven Deadly Sins or the “Seven Deadly Sins” are considered outdated teachings in the Church and are therefore ignored.

In this context, the author, who has specialized in philosophy and ethics for many years, explores the seven deadly vices in depth through "The Fascinating Vices," a book rooted in history, grounded in the Bible, and highly pastorally practical, drawing on the heavenly wisdom passed down through centuries of Christian moral tradition.

This book answers the central question: how can we bridge the gap between “a life consumed by vice and a life illuminated by beautiful virtue” (p. 15).

The book's central argument is that recovering a traditional Christian perspective on vice can help Christians and non-Christians better understand themselves, their culture, and the world, while also reconstructing Christian practices and cultivating virtue through habitual spiritual discipline.

Here, vice is defined as a corrupt and destructive habit, and virtue is defined as a habit that helps one to live well as a good human being.

The seven deadly sins are vanity, envy, sloth, greed, anger, gluttony, lust, and gluttony, and pride is their root.

The author describes the treatment for these vices as “systematizing self-reflection training and promoting lifelong spiritual formation.”

The author delves into the essential meaning of vices, arguing that these vices present a distorted path that subtly and deceptively mimics human goodness instead of God's goodness.

In this context, the author, who has specialized in philosophy and ethics for many years, explores the seven deadly vices in depth through "The Fascinating Vices," a book rooted in history, grounded in the Bible, and highly pastorally practical, drawing on the heavenly wisdom passed down through centuries of Christian moral tradition.

This book answers the central question: how can we bridge the gap between “a life consumed by vice and a life illuminated by beautiful virtue” (p. 15).

The book's central argument is that recovering a traditional Christian perspective on vice can help Christians and non-Christians better understand themselves, their culture, and the world, while also reconstructing Christian practices and cultivating virtue through habitual spiritual discipline.

Here, vice is defined as a corrupt and destructive habit, and virtue is defined as a habit that helps one to live well as a good human being.

The seven deadly sins are vanity, envy, sloth, greed, anger, gluttony, lust, and gluttony, and pride is their root.

The author describes the treatment for these vices as “systematizing self-reflection training and promoting lifelong spiritual formation.”

The author delves into the essential meaning of vices, arguing that these vices present a distorted path that subtly and deceptively mimics human goodness instead of God's goodness.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

introduction

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1 Why Study Vice?

Chapter 2: A Gift from the Desert: The Origins and History of the Tradition of Evil

Chapter 3 Vanity: Appearances Are Everything

Chapter 4: The bitter feeling of seeing others do better

Chapter 5: Sloth (Arcadia): Resistance to the Demands of Love

Chapter 6: Greed: Ownership and Control

Chapter 7 Anger: A Holy Emotion or a Hellish Emotion?

Chapter 8: Gluttony: Fattening the Face and Starving the Mind

Chapter 9: Lust: Sexuality Stripped Away

Chapter 10: The Journey Remains: Self-Examination, the Seven Deadly Sins, and Spiritual Formation

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1 Why Study Vice?

Chapter 2: A Gift from the Desert: The Origins and History of the Tradition of Evil

Chapter 3 Vanity: Appearances Are Everything

Chapter 4: The bitter feeling of seeing others do better

Chapter 5: Sloth (Arcadia): Resistance to the Demands of Love

Chapter 6: Greed: Ownership and Control

Chapter 7 Anger: A Holy Emotion or a Hellish Emotion?

Chapter 8: Gluttony: Fattening the Face and Starving the Mind

Chapter 9: Lust: Sexuality Stripped Away

Chapter 10: The Journey Remains: Self-Examination, the Seven Deadly Sins, and Spiritual Formation

Epilogue

Into the book

As I read Aquinas's account of the vice of timidity, I felt as if I were seeing myself in a mirror for the first time.

It gave a name to my inner conflict and helped me understand my anxiety and worthlessness.

At the same time, the biblical account of Moses provides moving evidence that God's power and grace can transform even our most vulnerable and fearful selves.

It was not Moses' timidity that determined his life, but God that determined his life.

--- From "Chapter 1: Why Study Vice?"

Vanity is easily confused with pride, the root of all evil.

These two vices, in particular, tend to be combined because they often compete for a spot on the list of the seven deadly sins.

Evagrius and Cassian considered pride and vanity as grave vices in their list of eight.

Later, Gregory I and Thomas Aquinas included vanity in their official list of the seven deadly vices, but they placed it among the seven, the ultimate source of all these vices: pride.

However, modern lists usually include pride among the seven and do not even mention vanity.

The television series “20/20,” which explores the seven deadly sins, included pride in its list, but defined it as “vanity,” confusing the desire to pursue excellence with the desire to show off that excellence to others.

--- From "Chapter 3 Vanity: Appearance is Everything"

In the film's first scene, Salieri attempts suicide, tormented by guilt over his involvement in Mozart's death.

A priest visits Salieri and hears his confession, which is reenacted throughout the rest of the film.

When the bride arrives, the aged Salieri is playing the piano in a wheelchair.

Salieri reveals that he is a composer and asks the confessor if he has ever received any musical training.

The priest replies that he had studied music a little in Vienna as a child, and Salieri seizes the opportunity to test his reputation.

He plays his own compositions one by one, hoping that the listener will find a familiar piece among them.

“This piece was very popular at the time,” says Salieri.

The priest shakes his head, embarrassed that he does not know any of them, and becomes enraged when Salieri continues to reveal his ignorance.

Then Salieri pauses for a moment.

“Just a moment!” he said, his eyes sparkling.

“How about this?” he says, playing the first verse of a brisk, short piece.

The bride almost immediately says, “Yes, yes, I know this song!” and continues humming it even after Salieri takes his hands off the keys.

He smiles at Salieri and looks very relieved.

“Oh, I like this song! I really like it.

sorry.

“I didn’t know you wrote this piece.” Salieri’s face darkens with a malicious expression and his eyes narrow.

“I didn’t write it,” he answers.

“It was Mozart.”

--- From "Chapter 4: The Bitter Feeling When Others Are Doing Better"

Why is it so difficult to share things? What drives us to acquire and cling to material possessions? Aquinas identifies two obstacles that hinder generosity by preventing us from giving up our possessions.

The first is that we sweat to get it.

If we have earned something through our own efforts, it will be more difficult to give.

Children may enjoy putting money in the offering box at church with their parents or using their parents' credit cards to buy new school clothes.

But once you become a teenager and start splitting what little you have earned, you suddenly become much less enthusiastic about giving.

We justify our actions by thinking that donating a little with our small income won't make much of a difference, or that we should save or spend enough first and then donate what's left.

Of course, this rationalization overlooks the purpose of giving as a way to cure the inner obsession with greed.

The purpose of these donations and sharing goes beyond helping the less fortunate, to correcting our desires and short-sighted views of where money comes from and where it is used.

God does not ask for our indiscriminate giving, but rather asks for our trust.

Our regular giving cultivates freedom and cultivates a reliance on God in our hearts.

--- From "Chapter 6 Greed: Possession and Domination"

Willard says, “Emotions are good servants, with a few exceptions.”

“But emotions are also terrible masters.” We judge the appropriateness of an expression of anger by whether it effectively achieves the goals of justice or destroys everything in its path.

The Greek virtue sophrosun?, which is difficult to translate but has a meaning close to “self-mastery” or “self-possession,” describes a person whose emotions fit into and support an overall picture of the good.

On the other hand, people who are angry or lack self-control are overwhelmed by anger, their vision of good narrows, and they paint the world red.

Anger seizes control as the self-proclaimed supreme commander.

--- From Chapter 7, Anger: A Holy Emotion or a Hellish Passion?

When we habitually misuse something, we tend to lose the ability to recognize its true value.

As with gluttony, the more we pursue something wholeheartedly and persistently to obtain pleasure, the less likely it is that our desire for pleasure will be satisfied.

Sexual masturbation gradually loses its taste.

What once felt ecstatic eventually becomes dull and boring.

Pornography viewing is a prime example of this dynamic, and the anti-drug organization Fight the New Drug provides ample documentation.

This data shows that pornography viewing (note how we talk about this activity in a consumerist way) is increasing at an alarming rate.

People who habitually watch pornography rapidly increase their frequency of viewing to the point where it interferes with and dominates their lives.

Meanwhile, the level of kinky, novel content required to pique their interest is rapidly escalating to the point where even jaded adults are shocked. Like drug dealers, the industry carefully designs experiences and exposure to maximize these progressive dynamics.

--- From "Chapter 9 Lust: Undressed Sexuality"

John Stott once said, “Holiness is not a state we attain by accident.”

One of my favorite cartoons is “Coffee with Jesus.”

In one episode, the main character, Carl, eloquently tells Jesus:

“Jesus, I love being a believer in you.

“You are a really good friend.”

“I’m glad you’re a believer, Carl!” Jesus replies.

“But I would like you to become my disciple.”

“What’s the difference?” Carl asks.

Jesus answers.

“It’s training.”

It gave a name to my inner conflict and helped me understand my anxiety and worthlessness.

At the same time, the biblical account of Moses provides moving evidence that God's power and grace can transform even our most vulnerable and fearful selves.

It was not Moses' timidity that determined his life, but God that determined his life.

--- From "Chapter 1: Why Study Vice?"

Vanity is easily confused with pride, the root of all evil.

These two vices, in particular, tend to be combined because they often compete for a spot on the list of the seven deadly sins.

Evagrius and Cassian considered pride and vanity as grave vices in their list of eight.

Later, Gregory I and Thomas Aquinas included vanity in their official list of the seven deadly vices, but they placed it among the seven, the ultimate source of all these vices: pride.

However, modern lists usually include pride among the seven and do not even mention vanity.

The television series “20/20,” which explores the seven deadly sins, included pride in its list, but defined it as “vanity,” confusing the desire to pursue excellence with the desire to show off that excellence to others.

--- From "Chapter 3 Vanity: Appearance is Everything"

In the film's first scene, Salieri attempts suicide, tormented by guilt over his involvement in Mozart's death.

A priest visits Salieri and hears his confession, which is reenacted throughout the rest of the film.

When the bride arrives, the aged Salieri is playing the piano in a wheelchair.

Salieri reveals that he is a composer and asks the confessor if he has ever received any musical training.

The priest replies that he had studied music a little in Vienna as a child, and Salieri seizes the opportunity to test his reputation.

He plays his own compositions one by one, hoping that the listener will find a familiar piece among them.

“This piece was very popular at the time,” says Salieri.

The priest shakes his head, embarrassed that he does not know any of them, and becomes enraged when Salieri continues to reveal his ignorance.

Then Salieri pauses for a moment.

“Just a moment!” he said, his eyes sparkling.

“How about this?” he says, playing the first verse of a brisk, short piece.

The bride almost immediately says, “Yes, yes, I know this song!” and continues humming it even after Salieri takes his hands off the keys.

He smiles at Salieri and looks very relieved.

“Oh, I like this song! I really like it.

sorry.

“I didn’t know you wrote this piece.” Salieri’s face darkens with a malicious expression and his eyes narrow.

“I didn’t write it,” he answers.

“It was Mozart.”

--- From "Chapter 4: The Bitter Feeling When Others Are Doing Better"

Why is it so difficult to share things? What drives us to acquire and cling to material possessions? Aquinas identifies two obstacles that hinder generosity by preventing us from giving up our possessions.

The first is that we sweat to get it.

If we have earned something through our own efforts, it will be more difficult to give.

Children may enjoy putting money in the offering box at church with their parents or using their parents' credit cards to buy new school clothes.

But once you become a teenager and start splitting what little you have earned, you suddenly become much less enthusiastic about giving.

We justify our actions by thinking that donating a little with our small income won't make much of a difference, or that we should save or spend enough first and then donate what's left.

Of course, this rationalization overlooks the purpose of giving as a way to cure the inner obsession with greed.

The purpose of these donations and sharing goes beyond helping the less fortunate, to correcting our desires and short-sighted views of where money comes from and where it is used.

God does not ask for our indiscriminate giving, but rather asks for our trust.

Our regular giving cultivates freedom and cultivates a reliance on God in our hearts.

--- From "Chapter 6 Greed: Possession and Domination"

Willard says, “Emotions are good servants, with a few exceptions.”

“But emotions are also terrible masters.” We judge the appropriateness of an expression of anger by whether it effectively achieves the goals of justice or destroys everything in its path.

The Greek virtue sophrosun?, which is difficult to translate but has a meaning close to “self-mastery” or “self-possession,” describes a person whose emotions fit into and support an overall picture of the good.

On the other hand, people who are angry or lack self-control are overwhelmed by anger, their vision of good narrows, and they paint the world red.

Anger seizes control as the self-proclaimed supreme commander.

--- From Chapter 7, Anger: A Holy Emotion or a Hellish Passion?

When we habitually misuse something, we tend to lose the ability to recognize its true value.

As with gluttony, the more we pursue something wholeheartedly and persistently to obtain pleasure, the less likely it is that our desire for pleasure will be satisfied.

Sexual masturbation gradually loses its taste.

What once felt ecstatic eventually becomes dull and boring.

Pornography viewing is a prime example of this dynamic, and the anti-drug organization Fight the New Drug provides ample documentation.

This data shows that pornography viewing (note how we talk about this activity in a consumerist way) is increasing at an alarming rate.

People who habitually watch pornography rapidly increase their frequency of viewing to the point where it interferes with and dominates their lives.

Meanwhile, the level of kinky, novel content required to pique their interest is rapidly escalating to the point where even jaded adults are shocked. Like drug dealers, the industry carefully designs experiences and exposure to maximize these progressive dynamics.

--- From "Chapter 9 Lust: Undressed Sexuality"

John Stott once said, “Holiness is not a state we attain by accident.”

One of my favorite cartoons is “Coffee with Jesus.”

In one episode, the main character, Carl, eloquently tells Jesus:

“Jesus, I love being a believer in you.

“You are a really good friend.”

“I’m glad you’re a believer, Carl!” Jesus replies.

“But I would like you to become my disciple.”

“What’s the difference?” Carl asks.

Jesus answers.

“It’s training.”

--- From "Chapter 10: The Remaining Journey: Self-Reflection, the Seven Fundamental Sins, and Spiritual Formation"

Publisher's Review

This book consists of a total of 10 chapters.

The first chapter presents five reasons why we still need to study vice today.

Chapter 2 traces the origins of the tradition of virtue and vice from Evagrius of Pontus to Aquinas and examines its development.

The author argues that the seven deadly sins are substitutes for the true desires of human beings, which are designed to be fulfilled only by an infinite and good God.

A deeper understanding of the seven deadly sins leads us to pursue self-knowledge and introduce “graceful disciplines” that we can practice daily as we rely on God’s grace to become more like Jesus Christ.

Chapter 3 distinguishes between pride as a desire for status and vanity as a desire for recognition and a good reputation.

Both of these vices are a disordered replacement for the human desire for glory, that is, the human desire to be known and accepted by God.

Chapter 4 defines envy as a cousin of greed, that is, a love that desires what another possesses.

Jealousy is fundamentally opposed to love for others.

To combat envy, we need a firm conviction in God's unconditional love, which enables us to affirm the gifts of others without feeling threatened or inferior.

Chapter 5 deals with the vice of sloth (Arcadia), which is characterized by resistance to the transforming demands of God's love.

The author warns against false rest and emphasizes the moral subjectivity of living each day in pursuit of one's identity in Christ.

Chapter 6 deals with greed, our inner obsession with money and possessions.

Disorderly attachments indicate a desire to replace God and are the opposite of generosity.

Regular giving cultivates freedom from greed and instills in people an attitude of dependence on God.

Chapter 7 describes anger as an expression of disordered rage that is contrary to humility.

The object of anger must be justice, and its root is love.

Biblical anger should express passion and love for our neighbors.

Chapter 8 details how gluttony, the excessive pursuit of pleasure in eating, can lead to a dulling of appreciation for the Creator who designed food and the pleasure of eating.

The author argues that eating should serve a spiritual function as an expression of humanity, and suggests regular fasting as a cure for gluttony.

Chapter 9 introduces lust, which is related to disordered sexual desire and pleasure.

The author argues that human sexuality is a good gift from God to build loving relationships that benefit human existence.

Lust destroys love between people, severing the relationship with God, and driving people into shame and isolation.

In the final chapter, the author likens sin to a tree, with pride as the root of the branches and the seven deadly sins as branches bearing characteristic fruit.

Pride, the main source of the seven deadly sins, replaces God, our ultimate good, with ourselves.

When we correctly recognize our wrong desires and their effects, we can move forward through confession and repentance, empowered by the Holy Spirit, into a new pattern of behavior that is comprehensive, specific, and communal.

This experiential and practical book offers countless vivid stories, concrete examples, culturally relevant narratives, personal testimonies, and actionable practices, empowering readers to escape the trap of sin and glimpse the glorious hope of complete salvation in Christ.

This book is a fascinating and timely contribution to the field of spiritual formation, particularly in a context of growing interest in life transformation to combat the secularization and ethical apathy of the Church.

Therefore, this book will be very helpful in inviting pastors and all Christians to more intentionally engage in lifelong change in the context of the Korean church, which has traditionally emphasized justification by faith and grace alone.

I strongly recommend this book to Christians who deeply reflect on the essence of Christian discipleship.

The first chapter presents five reasons why we still need to study vice today.

Chapter 2 traces the origins of the tradition of virtue and vice from Evagrius of Pontus to Aquinas and examines its development.

The author argues that the seven deadly sins are substitutes for the true desires of human beings, which are designed to be fulfilled only by an infinite and good God.

A deeper understanding of the seven deadly sins leads us to pursue self-knowledge and introduce “graceful disciplines” that we can practice daily as we rely on God’s grace to become more like Jesus Christ.

Chapter 3 distinguishes between pride as a desire for status and vanity as a desire for recognition and a good reputation.

Both of these vices are a disordered replacement for the human desire for glory, that is, the human desire to be known and accepted by God.

Chapter 4 defines envy as a cousin of greed, that is, a love that desires what another possesses.

Jealousy is fundamentally opposed to love for others.

To combat envy, we need a firm conviction in God's unconditional love, which enables us to affirm the gifts of others without feeling threatened or inferior.

Chapter 5 deals with the vice of sloth (Arcadia), which is characterized by resistance to the transforming demands of God's love.

The author warns against false rest and emphasizes the moral subjectivity of living each day in pursuit of one's identity in Christ.

Chapter 6 deals with greed, our inner obsession with money and possessions.

Disorderly attachments indicate a desire to replace God and are the opposite of generosity.

Regular giving cultivates freedom from greed and instills in people an attitude of dependence on God.

Chapter 7 describes anger as an expression of disordered rage that is contrary to humility.

The object of anger must be justice, and its root is love.

Biblical anger should express passion and love for our neighbors.

Chapter 8 details how gluttony, the excessive pursuit of pleasure in eating, can lead to a dulling of appreciation for the Creator who designed food and the pleasure of eating.

The author argues that eating should serve a spiritual function as an expression of humanity, and suggests regular fasting as a cure for gluttony.

Chapter 9 introduces lust, which is related to disordered sexual desire and pleasure.

The author argues that human sexuality is a good gift from God to build loving relationships that benefit human existence.

Lust destroys love between people, severing the relationship with God, and driving people into shame and isolation.

In the final chapter, the author likens sin to a tree, with pride as the root of the branches and the seven deadly sins as branches bearing characteristic fruit.

Pride, the main source of the seven deadly sins, replaces God, our ultimate good, with ourselves.

When we correctly recognize our wrong desires and their effects, we can move forward through confession and repentance, empowered by the Holy Spirit, into a new pattern of behavior that is comprehensive, specific, and communal.

This experiential and practical book offers countless vivid stories, concrete examples, culturally relevant narratives, personal testimonies, and actionable practices, empowering readers to escape the trap of sin and glimpse the glorious hope of complete salvation in Christ.

This book is a fascinating and timely contribution to the field of spiritual formation, particularly in a context of growing interest in life transformation to combat the secularization and ethical apathy of the Church.

Therefore, this book will be very helpful in inviting pastors and all Christians to more intentionally engage in lifelong change in the context of the Korean church, which has traditionally emphasized justification by faith and grace alone.

I strongly recommend this book to Christians who deeply reflect on the essence of Christian discipleship.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: September 6, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 508 pages | 152*225*35mm

- ISBN13: 9791161292892

- ISBN10: 1161292896

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)