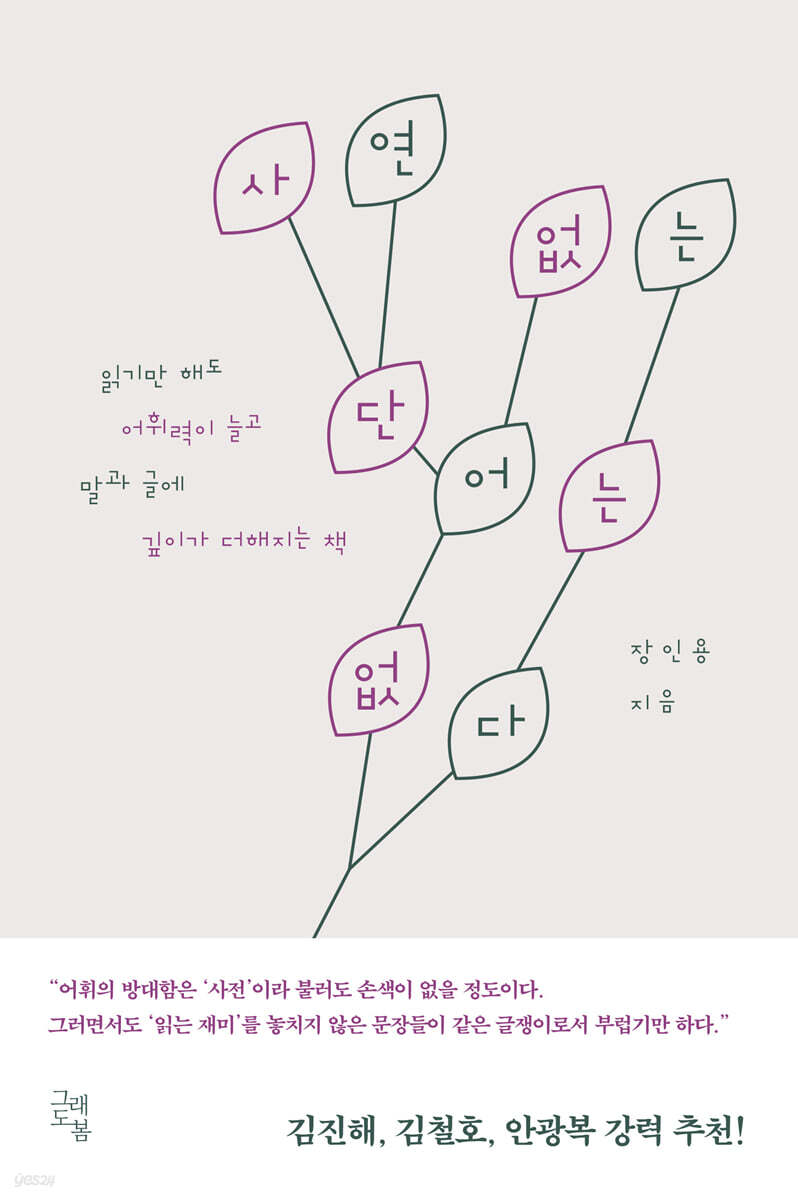

There is no word without a story.

|

Description

Book Introduction

★Highly recommended by Kim Jin-hae, Kim Cheol-ho, and Ahn Gwang-bok!★

Understand the meaning and usage of words properly

A dictionary of words that enriches our lives

The power of etymology to further enhance literacy, vocabulary, and expressiveness!

The book 『There Are No Words Without a Story』, which highlights the humanistic exploration of author Jang In-yong, who has been a publisher in the humanities and science fields for over 30 years and has now stepped back from the front lines to devote himself to writing, has been published.

The author explores the etymology, history, and cultural context of words, and provides an engaging account of the real meanings and uses of the words we use, as well as the stories behind them.

In this book, which consists of seven parts, the most noteworthy part is the part that explores the process of language change and convergence through the stories contained in Chinese characters translated by Japan, such as 'danji (團地)' or 'gosubuji (高水敷地)', 'economy', and 'society'.

You can also discover the origins of words derived from Chinese characters, the secrets behind the names of trees, fish, vegetables, and fruits that are difficult to find in other etymology books, the origins of place names and religious terms, and interesting linguistic clues found in homonyms and conjugated words.

Just as everything in the world has a beginning, the words we use also have a beginning if we trace them back.

The journey of exploring the essence of words is as fun as a tale from the past, as it involves finding traces of the past engraved in words.

It also helps you use vocabulary accurately as you gain knowledge about the language.

It is useful for improving literacy, vocabulary, and even expressive skills.

We learn, communicate, and live through knowledge, civilization, history, and literature through texts written in Korean.

Only when we know the etymology of a word can we understand its meaning more deeply and broaden our perspective on the world.

I hope that through this book, you will be able to properly understand the meaning and usage of words and experience the joy of adding culture to your life.

Understand the meaning and usage of words properly

A dictionary of words that enriches our lives

The power of etymology to further enhance literacy, vocabulary, and expressiveness!

The book 『There Are No Words Without a Story』, which highlights the humanistic exploration of author Jang In-yong, who has been a publisher in the humanities and science fields for over 30 years and has now stepped back from the front lines to devote himself to writing, has been published.

The author explores the etymology, history, and cultural context of words, and provides an engaging account of the real meanings and uses of the words we use, as well as the stories behind them.

In this book, which consists of seven parts, the most noteworthy part is the part that explores the process of language change and convergence through the stories contained in Chinese characters translated by Japan, such as 'danji (團地)' or 'gosubuji (高水敷地)', 'economy', and 'society'.

You can also discover the origins of words derived from Chinese characters, the secrets behind the names of trees, fish, vegetables, and fruits that are difficult to find in other etymology books, the origins of place names and religious terms, and interesting linguistic clues found in homonyms and conjugated words.

Just as everything in the world has a beginning, the words we use also have a beginning if we trace them back.

The journey of exploring the essence of words is as fun as a tale from the past, as it involves finding traces of the past engraved in words.

It also helps you use vocabulary accurately as you gain knowledge about the language.

It is useful for improving literacy, vocabulary, and even expressive skills.

We learn, communicate, and live through knowledge, civilization, history, and literature through texts written in Korean.

Only when we know the etymology of a word can we understand its meaning more deeply and broaden our perspective on the world.

I hope that through this book, you will be able to properly understand the meaning and usage of words and experience the joy of adding culture to your life.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommendation

In publishing the book

Part 1: Words with new meanings

Old and New Economy

Between society and religion

wife, wife, housewife, lady

Father-uncle, Mother-aunt

Brother, sister, older sister, younger sibling, classmate

West, young master, old woman

Tin Cans and Thugs

Past, Present, Future

A word that is elevated by adding '하' (below)

Foreign country names and Chinese characters

Words like 'democracy, National Assembly, court, trade'

Part 2: Words with Reversed Meanings

slow-witted, quiet, reserved, and drunk

Misreading Idioms ①: Day and night, unison, three-legged mountain

Misreading Idioms ②: Scattered and scattered, distinguishing between good and evil, sharing joys and sorrows together

The formation of '~no' ①: Things that have become fixed as one word

The Formation of '~hasn't' ②: Why It Was Not Recognized as a Single Word

The formation of '~no' ③: When the original meaning changes

By chance and coincidence

Fun, taste and style

Part 3: Words that are more fun when you know their origins

Plants that resemble chickens and pheasants

Boat bridge, wooden bridge, wooden bridge

Fish Name ①: Squid, Mackerel

Fish Name ②: Carp, Carp, Shark

Fish Name ③: Mackerel, oyster, pollack, and dried pollack

Flowers, skewers, crabs, and icicles

Kimchi, jangji, kkakdugi

Lettuce, spinach, eggplant, melon, pumpkin

Fruit names

Tree name

Color name

Cider, wafers, and knitwear

Part 4: Words that cause misunderstandings by changing or distinguishing them into Chinese characters

Moraenae and Gajaegol, Sacheon Bridge and Gajwa-dong

That apple is not boring

Chinese character homonyms ①: Proofreading and revision

Chinese character homonyms ②: Place names and consecutive defeats

Words derived from punishment

Words that begin with 'water'

Chinese characters that are read differently

Katabuta, colorful, hesitant

Part 5: Our language and the words that are indispensable

Anyway, so, of course, of course

What the heck and on earth

If and for example

Bags and shoes

pot

Sundae and in-laws

You tell her

① I'm not sure if it's a Chinese character or not: It's trivial, it's lonely

② I'm not sure if it's a Chinese character or not: As usual, later, for a moment, quietly

A word that sounds like a Chinese character but is actually a Korean word

Vocabulary mixed with Chinese characters and Korean words

Part 6: Words that make studying easier

rhombus, sector

Lee Seon-ran's mathematical terminology

The birth of the universe, the Earth, and the sun

Korean language and science

The two-letter instinct of 'history, philosophy, music, and art'

Physics, chemistry, and medical terms

Dutch translation

Sports terms

Part 7: Words from Religion

Dabansa and Ipansapan

Entrance and exit

chaos, chaos, chaos, hell

Everyday Terms Originating from Buddhism ①: Nouns

Everyday Terms Originating from Buddhism ②: Buddhist Terms You Might Not Have Thought About

Everyday Terms Originating from Buddhism ③: Words That Permeate Us Knowingly or Unknowingly

priest, pastor, elder

Buddhist terms borrowed from Christianity

Search

In publishing the book

Part 1: Words with new meanings

Old and New Economy

Between society and religion

wife, wife, housewife, lady

Father-uncle, Mother-aunt

Brother, sister, older sister, younger sibling, classmate

West, young master, old woman

Tin Cans and Thugs

Past, Present, Future

A word that is elevated by adding '하' (below)

Foreign country names and Chinese characters

Words like 'democracy, National Assembly, court, trade'

Part 2: Words with Reversed Meanings

slow-witted, quiet, reserved, and drunk

Misreading Idioms ①: Day and night, unison, three-legged mountain

Misreading Idioms ②: Scattered and scattered, distinguishing between good and evil, sharing joys and sorrows together

The formation of '~no' ①: Things that have become fixed as one word

The Formation of '~hasn't' ②: Why It Was Not Recognized as a Single Word

The formation of '~no' ③: When the original meaning changes

By chance and coincidence

Fun, taste and style

Part 3: Words that are more fun when you know their origins

Plants that resemble chickens and pheasants

Boat bridge, wooden bridge, wooden bridge

Fish Name ①: Squid, Mackerel

Fish Name ②: Carp, Carp, Shark

Fish Name ③: Mackerel, oyster, pollack, and dried pollack

Flowers, skewers, crabs, and icicles

Kimchi, jangji, kkakdugi

Lettuce, spinach, eggplant, melon, pumpkin

Fruit names

Tree name

Color name

Cider, wafers, and knitwear

Part 4: Words that cause misunderstandings by changing or distinguishing them into Chinese characters

Moraenae and Gajaegol, Sacheon Bridge and Gajwa-dong

That apple is not boring

Chinese character homonyms ①: Proofreading and revision

Chinese character homonyms ②: Place names and consecutive defeats

Words derived from punishment

Words that begin with 'water'

Chinese characters that are read differently

Katabuta, colorful, hesitant

Part 5: Our language and the words that are indispensable

Anyway, so, of course, of course

What the heck and on earth

If and for example

Bags and shoes

pot

Sundae and in-laws

You tell her

① I'm not sure if it's a Chinese character or not: It's trivial, it's lonely

② I'm not sure if it's a Chinese character or not: As usual, later, for a moment, quietly

A word that sounds like a Chinese character but is actually a Korean word

Vocabulary mixed with Chinese characters and Korean words

Part 6: Words that make studying easier

rhombus, sector

Lee Seon-ran's mathematical terminology

The birth of the universe, the Earth, and the sun

Korean language and science

The two-letter instinct of 'history, philosophy, music, and art'

Physics, chemistry, and medical terms

Dutch translation

Sports terms

Part 7: Words from Religion

Dabansa and Ipansapan

Entrance and exit

chaos, chaos, chaos, hell

Everyday Terms Originating from Buddhism ①: Nouns

Everyday Terms Originating from Buddhism ②: Buddhist Terms You Might Not Have Thought About

Everyday Terms Originating from Buddhism ③: Words That Permeate Us Knowingly or Unknowingly

priest, pastor, elder

Buddhist terms borrowed from Christianity

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

The word 'economy' originally had an enlightening character, meaning 'to set the world right and save the people.'

Hong Man-seon wrote this book with the intention of teaching the ignorant people correctly and making the world a better place to live.

So why did "economy" have such a different meaning? It's because the Japanese, while translating Western terminology, translated "economy" as "economy."

In the process, the traditional Confucian concepts that this word contained disappeared, leaving only the concepts of Western languages.

As the world changes, words change too.

When we start using words with different meanings depending on the times, the old meanings quickly disappear.

In any case, I think it will be difficult to see any more unique word creation techniques that combine Chinese characters with foreign words influenced by Japanese, such as 'kangtong' (can) and 'gangpae' (thug).

First of all, there is no importing of foreign words with Japanese pronunciation.

And it has become more difficult to add appropriate Chinese characters such as ‘통’ and ‘패’.

Because the general public's sensitivity to Chinese characters has declined significantly, even if Chinese characters are added, it will not be as easy to accept them as before.

Nowadays, it is common for elementary school students and teenagers to have good Chinese character skills.

However, they are not the generation that used to mix Chinese characters in newspapers and books.

--- From “Part 1: Words with Changed Meanings and New Uses”

We say 'acting rashly and without any reason' as 'reckless'.

It can't be good for people to call me a swindler.

However, if you look it up in the dictionary, the first definition that comes up is 'a consistently established claim or judgment.'

It is not a negative term, but rather a reference to a desirable state.

The original word for '주책' is '주착(主着)', and here '착(果)', like '도착(到着)', means 'being doing something', so this interpretation is acceptable.

However, it is rarely used in a positive sense and is only used as an expression such as ‘to act rashly’ or ‘to act rashly’.

The word 'chilchilhada', which means 'to do things neatly and neatly', also seems to be combining with the negative words 'anhda' or 'mothada', and its original positive meaning is being reversed.

Even words with good meanings like this often have their meanings reversed when combined with negative descriptive forms such as 'no', 'not', 'can't', and 'don't know'.

Even if the negative description is omitted, the connotation still remains.

If a good person is always with a bad person, it is easier for the good person to become bad than for the bad person to become good.

The fact that 'fun', 'taste', and 'style' all mean the same thing reminds us that human life was not originally that complicated.

Ultimately, eating comes first for people, and to eat well, it has to taste good.

Then, when it becomes abundant, it develops into play or art.

In some ways, fun, taste, and style can be almost everything in our lives and happiness.

So, even though there are many words with the word '~no', it seems like they can't overcome the usage of 'fun', 'delicious', and 'cool'.

--- From "Part 2: Words with Reversed Meanings"

What is being sold as squid at fish markets now is not squid in terms of biological taxonomy, but a type of cuttlefish.

Perhaps, eventually, these fakes will take over the name 'squid', but the real squid, 'gap squid', is destined to have the letter 'gap' in front of its name.

The original name of what we now call 'squid' is 'pidungeokkoldtugi', a type of squid.

In Jeong Yak-jeon's "Jasaneobo (玆山魚譜)", he quotes an old book and says that the name "squid" comes from the Chinese character "오적 (烏賊)".

The name is said to have originated from the fact that squid pretend to be dead in the sea to lure crows and eat them.

Of course, this means 'squid'.

We call carbonated water with flavoring and sugar 'cider'.

Along with cola, this has solidified its position as a synonym for carbonated beverages.

It is so refreshing that the adjective 'like cider' is used to describe refreshing words.

The origin of this name is clearly the English word 'Cider'.

However, this does not refer to a carbonated beverage with flavoring and sugar, but rather to juice or alcohol made from apple juice.

--- From "Words That Are More Interesting When You Know Their Origins"

There are quite a few Chinese characters that are read with different pronunciations.

Punctuation marks such as commas and periods should not be read as ‘gudokjeom’, going around giving speeches should not be read as ‘yuseol’, sinking into water should not be read as ‘simmol’, and ‘hangnyeol’, which means blood relations, should not be read as ‘haengnyeol’.

'Saenggyak (省略),' which means 'to reduce or subtract,' should not be read as 'seongryak,' and 'alhyeon (謁見),' which means to meet a high-ranking person, should not be read as 'algyeon,' as the listener will not understand, and 'gangwoo (降雨),' which means it is raining, is the same character as 'hang' in 'surrender,' which means to raise both hands in defeat in a fight, but is read differently.

--- From “Part 4 Words that cause misunderstandings by changing or distinguishing them into Chinese characters”

There are many adverbs that sound like Korean at first glance.

But if you look closely, there are quite a few adverbs that originate from Chinese characters.

The reason why there are so many adverbs that are derived from Chinese characters is because we have been using Chinese characters for a long time.

Of course, there are countless words in general vocabulary that are derived from Chinese characters, but a significant portion of adverbs used as conjunctions also rely on Chinese characters.

As time passed, it came to be considered almost like our own language, and its meaning gradually changed from its original meaning.

In fact, when we look into the etymology of words, there are many things whose origins are unknown.

At this point, these words are no longer Chinese characters, but rather Korean words.

There are quite a few nouns that are derived from Chinese characters, which are like native words.

'Piri' is a musical instrument name derived from the Chinese character 'pilryul (??)', and 'nakji' is a name derived from 'rakje (絡蹄)'.

The word 'bidan' is a word that came from the word 'pildan', and 'magoja' is a word that came from 'magwaeja'.

'Geumsil', which means between a married couple, comes from 'Geumseul', and 'jujube', which ripens in the fall, comes from 'daejo'.

The 'drawer' attached to a desk or furniture is a modified form of the Chinese character '설합(舌盒)' which means 'a box that can be put in and taken out like a tongue', and the word '양재기' for a bowl made of enamel or aluminum is a modified form of '양자기(洋磁器)' which means 'porcelain bowl brought over from the West', and '절구(杵臼)' is a modified form of the Chinese character '적구(杵臼)'.

As such, there are countless Korean words that originated from Chinese characters.

Among these, those whose sounds have changed can be considered to have already been completely naturalized into our language.

So, these words are not written in Chinese characters in parentheses in the Korean dictionary.

--- From “Part 5: Our Language or Unparalleled Words”

Mathematical terms contain too many Chinese characters.

Of course, not only in mathematics, but also in physics and biology, there are many difficult Chinese character terms, and even more so in social sciences such as law and economics.

Since most Western learning came through Japan, there is also that aspect of using Chinese character terms translated by Japan.

It is also because Chinese characters are convenient for making simple forms of words.

So, even after directly encountering Western scholarship, there are times when I refer to Japanese translations to determine translation terminology.

In our country, the expression ‘national language’ first appeared in the Official Gazette in 1895.

At this time, before the establishment of the Korean Empire, ‘national language’ referred to ‘Joseon language.’

At that time, China had not yet used the word 'national language', so the 'national language' at that time was likely a coined word that had been brought in through Japan.

Even so, in these times of uncertainty, our ancestors cherished their country and language through the expression ‘national language.’

The Korean language did not disappear immediately after the Japanese colonial period.

However, with the annexation of Korea by Japan, Korean became Japanese, and Joseon was relegated to a second language.

The Korean language was sacrificed to the policy of eradicating the Korean language implemented by the Japanese in 1937, but regained its position as the national language after liberation.

--- From "Part 6: Words That Make Studying Easier"

In Buddhism, the meaning of 'Talak' is a good one, meaning 'to break free from attachment and achieve liberation of body and mind.'

Liberation is a stage of attainment, so it must be a joy that transcends the mundane.

But how did a word with a positive religious meaning end up meaning something that means falling behind and falling behind in reality? Perhaps religious fulfillment means escaping the secular world, and separating from it means falling behind in reality.

Religious values and secular values cannot be the same.

'Falling out' may be a goal in religion, but it cannot be a goal in reality.

Hong Man-seon wrote this book with the intention of teaching the ignorant people correctly and making the world a better place to live.

So why did "economy" have such a different meaning? It's because the Japanese, while translating Western terminology, translated "economy" as "economy."

In the process, the traditional Confucian concepts that this word contained disappeared, leaving only the concepts of Western languages.

As the world changes, words change too.

When we start using words with different meanings depending on the times, the old meanings quickly disappear.

In any case, I think it will be difficult to see any more unique word creation techniques that combine Chinese characters with foreign words influenced by Japanese, such as 'kangtong' (can) and 'gangpae' (thug).

First of all, there is no importing of foreign words with Japanese pronunciation.

And it has become more difficult to add appropriate Chinese characters such as ‘통’ and ‘패’.

Because the general public's sensitivity to Chinese characters has declined significantly, even if Chinese characters are added, it will not be as easy to accept them as before.

Nowadays, it is common for elementary school students and teenagers to have good Chinese character skills.

However, they are not the generation that used to mix Chinese characters in newspapers and books.

--- From “Part 1: Words with Changed Meanings and New Uses”

We say 'acting rashly and without any reason' as 'reckless'.

It can't be good for people to call me a swindler.

However, if you look it up in the dictionary, the first definition that comes up is 'a consistently established claim or judgment.'

It is not a negative term, but rather a reference to a desirable state.

The original word for '주책' is '주착(主着)', and here '착(果)', like '도착(到着)', means 'being doing something', so this interpretation is acceptable.

However, it is rarely used in a positive sense and is only used as an expression such as ‘to act rashly’ or ‘to act rashly’.

The word 'chilchilhada', which means 'to do things neatly and neatly', also seems to be combining with the negative words 'anhda' or 'mothada', and its original positive meaning is being reversed.

Even words with good meanings like this often have their meanings reversed when combined with negative descriptive forms such as 'no', 'not', 'can't', and 'don't know'.

Even if the negative description is omitted, the connotation still remains.

If a good person is always with a bad person, it is easier for the good person to become bad than for the bad person to become good.

The fact that 'fun', 'taste', and 'style' all mean the same thing reminds us that human life was not originally that complicated.

Ultimately, eating comes first for people, and to eat well, it has to taste good.

Then, when it becomes abundant, it develops into play or art.

In some ways, fun, taste, and style can be almost everything in our lives and happiness.

So, even though there are many words with the word '~no', it seems like they can't overcome the usage of 'fun', 'delicious', and 'cool'.

--- From "Part 2: Words with Reversed Meanings"

What is being sold as squid at fish markets now is not squid in terms of biological taxonomy, but a type of cuttlefish.

Perhaps, eventually, these fakes will take over the name 'squid', but the real squid, 'gap squid', is destined to have the letter 'gap' in front of its name.

The original name of what we now call 'squid' is 'pidungeokkoldtugi', a type of squid.

In Jeong Yak-jeon's "Jasaneobo (玆山魚譜)", he quotes an old book and says that the name "squid" comes from the Chinese character "오적 (烏賊)".

The name is said to have originated from the fact that squid pretend to be dead in the sea to lure crows and eat them.

Of course, this means 'squid'.

We call carbonated water with flavoring and sugar 'cider'.

Along with cola, this has solidified its position as a synonym for carbonated beverages.

It is so refreshing that the adjective 'like cider' is used to describe refreshing words.

The origin of this name is clearly the English word 'Cider'.

However, this does not refer to a carbonated beverage with flavoring and sugar, but rather to juice or alcohol made from apple juice.

--- From "Words That Are More Interesting When You Know Their Origins"

There are quite a few Chinese characters that are read with different pronunciations.

Punctuation marks such as commas and periods should not be read as ‘gudokjeom’, going around giving speeches should not be read as ‘yuseol’, sinking into water should not be read as ‘simmol’, and ‘hangnyeol’, which means blood relations, should not be read as ‘haengnyeol’.

'Saenggyak (省略),' which means 'to reduce or subtract,' should not be read as 'seongryak,' and 'alhyeon (謁見),' which means to meet a high-ranking person, should not be read as 'algyeon,' as the listener will not understand, and 'gangwoo (降雨),' which means it is raining, is the same character as 'hang' in 'surrender,' which means to raise both hands in defeat in a fight, but is read differently.

--- From “Part 4 Words that cause misunderstandings by changing or distinguishing them into Chinese characters”

There are many adverbs that sound like Korean at first glance.

But if you look closely, there are quite a few adverbs that originate from Chinese characters.

The reason why there are so many adverbs that are derived from Chinese characters is because we have been using Chinese characters for a long time.

Of course, there are countless words in general vocabulary that are derived from Chinese characters, but a significant portion of adverbs used as conjunctions also rely on Chinese characters.

As time passed, it came to be considered almost like our own language, and its meaning gradually changed from its original meaning.

In fact, when we look into the etymology of words, there are many things whose origins are unknown.

At this point, these words are no longer Chinese characters, but rather Korean words.

There are quite a few nouns that are derived from Chinese characters, which are like native words.

'Piri' is a musical instrument name derived from the Chinese character 'pilryul (??)', and 'nakji' is a name derived from 'rakje (絡蹄)'.

The word 'bidan' is a word that came from the word 'pildan', and 'magoja' is a word that came from 'magwaeja'.

'Geumsil', which means between a married couple, comes from 'Geumseul', and 'jujube', which ripens in the fall, comes from 'daejo'.

The 'drawer' attached to a desk or furniture is a modified form of the Chinese character '설합(舌盒)' which means 'a box that can be put in and taken out like a tongue', and the word '양재기' for a bowl made of enamel or aluminum is a modified form of '양자기(洋磁器)' which means 'porcelain bowl brought over from the West', and '절구(杵臼)' is a modified form of the Chinese character '적구(杵臼)'.

As such, there are countless Korean words that originated from Chinese characters.

Among these, those whose sounds have changed can be considered to have already been completely naturalized into our language.

So, these words are not written in Chinese characters in parentheses in the Korean dictionary.

--- From “Part 5: Our Language or Unparalleled Words”

Mathematical terms contain too many Chinese characters.

Of course, not only in mathematics, but also in physics and biology, there are many difficult Chinese character terms, and even more so in social sciences such as law and economics.

Since most Western learning came through Japan, there is also that aspect of using Chinese character terms translated by Japan.

It is also because Chinese characters are convenient for making simple forms of words.

So, even after directly encountering Western scholarship, there are times when I refer to Japanese translations to determine translation terminology.

In our country, the expression ‘national language’ first appeared in the Official Gazette in 1895.

At this time, before the establishment of the Korean Empire, ‘national language’ referred to ‘Joseon language.’

At that time, China had not yet used the word 'national language', so the 'national language' at that time was likely a coined word that had been brought in through Japan.

Even so, in these times of uncertainty, our ancestors cherished their country and language through the expression ‘national language.’

The Korean language did not disappear immediately after the Japanese colonial period.

However, with the annexation of Korea by Japan, Korean became Japanese, and Joseon was relegated to a second language.

The Korean language was sacrificed to the policy of eradicating the Korean language implemented by the Japanese in 1937, but regained its position as the national language after liberation.

--- From "Part 6: Words That Make Studying Easier"

In Buddhism, the meaning of 'Talak' is a good one, meaning 'to break free from attachment and achieve liberation of body and mind.'

Liberation is a stage of attainment, so it must be a joy that transcends the mundane.

But how did a word with a positive religious meaning end up meaning something that means falling behind and falling behind in reality? Perhaps religious fulfillment means escaping the secular world, and separating from it means falling behind in reality.

Religious values and secular values cannot be the same.

'Falling out' may be a goal in religion, but it cannot be a goal in reality.

--- From "Part 7: Words Derived from Religion"

Publisher's Review

"The words are warm and the reading is a delight." _Professor Kim Jin-hae of Kyunghee University, author of "The End of Your Words is You"

“The vocabulary is so vast that it could easily be called a dictionary.” _Kim Cheol-ho, author of “Un-Da-Ri-Gwa-Da-Ri-Gwa”

“If you’re worried about your Korean language skills, I highly recommend reading this.” _Ahn Gwang-bok, philosophy teacher, author of “The Power of Writing One A4 Page”

“Where did that word come from?”

By capturing the subtle differences in vocabulary and using words appropriately,

The power of etymology to further enhance literacy, vocabulary, and expressiveness!

_Beyond linguistic literacy, to communication and empathy in life!

There are people who think they know Korean well and therefore don't need to study the language.

The language we use contains vocabulary, expressions, and cultural contexts that have been formed over a long period of time.

In particular, the Korean language has developed over a long history under the influence of various foreign words and Chinese characters.

The influence of Buddhism, which was introduced as a foreign religion, was deeply engraved in our language and must have had a great influence on the creation of Hangul.

Also, in modern times, the influence of Japan cannot be ignored.

The Japanese colonial period was a time when Japanese influence was at its peak, and after liberation, American culture and English language flooded in.

This 'infection' of language caused old words to be forgotten while at the same time creating new ones.

A few years ago, online, there was a heated debate over declining literacy, with comments like, “‘A boring apology’? I’m not bored at all,” “Does a three-day holiday mean four days off?” and “Does having high knowledge mean you have high level of knowledge?”

Misunderstandings and lack of empathy resulting from subtle differences in vocabulary or an inability to flexibly interpret the meaning of sentences have become a major topic of discussion across modern society, not just between generations.

The linguistic skills we must possess in modern times go beyond simply speaking and writing; they have become essential for enhancing empathy and communication skills and for gaining a deeper understanding of the world.

We can feel history, culture, and people's lives that we were unaware of through everyday words that we use without thinking.

Understanding how language has formed and changed empowers us to understand the meaning of words more deeply and use language more effectively.

Just as everything in the world has a beginning, the words we use also have a beginning if we trace them back.

The journey of exploring the essence of words is as fun as a tale from the past, as it involves finding traces of the past engraved in words.

It also helps you use vocabulary accurately because you can gain knowledge about words.

It is useful for improving literacy, vocabulary, and even expressive skills.

We learn, communicate, and live through knowledge, civilization, history, and literature through texts written in Korean.

Only when we know the etymology of a word can we understand its meaning more deeply and broaden our perspective on the world.

Etymology is a window into fully understanding the language we use and the world it creates.

With insight into the flow and relationships of the world

Developing the ability to understand and imagine the context of words

_History and culture, customs and social consciousness entangled in words

Author Jang In-yong, who has worked as a publisher for over 30 years and is now devoted to writing, lives a life inseparable from language.

The number of humanities and science books that passed through his hands is countless, and his outstanding linguistic sense and humanist perspective displayed in his books 『The Color of Hanja』, 『Zhou Dynasty and Joseon』, 『Food and Drink』, and his translation of 『History of Chinese Art』 have garnered attention from both academics and readers.

And that's not all.

In his youth, he was introduced to bronze inscriptions (characters carved or cast on bronzeware) and learned paleography. During his time at Deep-Rooted Tree, he was able to learn about the Korean language from CEO Han Chang-gi, who was called the “aesthetic genius of the Korean cultural world,” and thanks to this, he was able to create Professor Seo Jeong-su’s “Korean Grammar.”

That foundation would have been helpful in writing this book.

Author Jang In-yong went on a long journey for several years to find the stories behind words.

In his book, “Preface,” he stated:

“I’ve been writing all my life, and I’ve always had a casual interest in etymology, but I’ve never really delved into it.

I doubted whether I could write something like this, and as I began reading books and papers on etymology, I wondered whether I could write something different from existing etymology books.

“The conclusion is that I thought that if I covered a broader scope than the existing etymology, I could write an etymology book with my own unique personality.”

There is a lot of content in 『There is No Word Without a Story』 that is not covered in other etymology books.

For example, we looked at Chinese characters translated by Japan, such as 'danji (團地)' or 'gosubuji (高水敷地)' or 'economy' and 'society', and explored the process of language change and convergence through the stories contained in them.

This book also includes the origins of many words derived from Chinese characters that the author discovered while learning Chinese.

It also introduces the secrets behind the names of trees, fish, vegetables, and fruits, the origins of place names and religious terms, and interesting linguistic clues found in homonyms and consonants.

The author says that the reason for covering such a wide range of fields is because he hopes that readers will find a little more enjoyment in the Korean language through the hidden meanings in the words.

In particular, rather than focusing on explaining each word individually, this book helps you use words appropriately by linking them together and talking about them.

For example, wife, wife, housewife, and wife all refer to one person, but the author adds his or her opinion by clarifying that there are differences in context and nuance.

In this book, you can discover the hidden stories behind the words we use without thinking.

It carefully strips away the tangled history, culture, customs, and social consciousness of language.

It leads to the development of the power to understand and imagine the context of words, not through knowledge of individual phenomena, but through insight into the flow of the world and the relationships between them.

Part 1 deals with 'words that have changed meanings and are being used anew.'

It shows that language has constantly evolved to adapt to the times and environment through modern reinterpretations of words like 'economy,' 'society,' 'law,' and 'company,' combinations of foreign words and Chinese characters like 'can' and 'gangster,' and examples of Western concepts like 'democracy,' 'National Assembly,' and 'court.'

Part 2 is about 'words with reversed meanings'.

The adaptability and flexibility of language are explored through examples of positive meanings being changed to negative ones, such as 'sukmaek', 'yamche', and 'juchaek', and examples of expressions that should have opposite meanings being used with similar meanings, such as 'uyeonhi' and 'uyeonchange'.

It shows how language is given new meaning and evolves depending on the context in which it is used.

Part 3 introduces 'words that are more fun when you know their origins.'

It explores the connections between plants and animals, such as 'pheasant's leg' and 'mandrami', the origins of place names and bridges, such as 'baedari' and 'seopdari', the origins of fish names, such as 'squid', 'galchi' and 'myeongtae', the names and history of foods, such as 'kimchi' and 'kkakdugi', as well as the origins of colors, foreign crops, and trees.

Discover the history and culture contained in everyday words, and vividly convey the excitement and joy that language conveys.

Part 4 delves into 'words that cause confusion by being changed or distinguished into Chinese characters.'

This article deals with cases where emotional place names disappeared, with only administrative convenience remaining, such as 'Moraenae' changing to 'Sacheon' and 'Gajaegol' changing to 'Gajwadong'.

It also explores the impact of language change and the resulting breakdown in understanding through the confusion caused by Chinese character homonyms and the misunderstandings resulting from pronunciation diversity.

Part 5 deals with ‘Korean language and non-Korean language.’

It talks about the convergence and change of language through words that originated from Chinese characters but lost their original meanings through long-term use, such as '여하', '예시', '도대체', and '면'; new words that were created by combining Chinese characters and pure Korean words, such as '설소리하다', '호락호락', and '양치질'; and examples of foreign words transformed into Korean, such as '가방' and '구두'.

Part 6 explains the origins and accessibility of learning terms under the theme of “Words that make studying easier.”

In mathematics, the word 'function' (函數) originally comes from the Chinese character meaning 'box', but it is used without sufficient explanation and is perceived as difficult, whereas Korean expressions such as 'rhombus' and 'fan' are presented as positive examples that help understand the concept.

Furthermore, it provides an interesting historical background that made it inevitable for terms like "national language" (national language) and "science" (science) to be used, which were introduced through Japan, and emphasizes the importance of linguistic changes that increase the accessibility and efficiency of learning.

Part 7, titled 'Words Originating from Religion', shows that many of the words we use in our daily lives have their origins in religions such as Buddhism.

'Dabansa' originated from the fact that tea and rice were a daily occurrence in temples, and 'Ipansapan' originated from the distinction of roles among monks, but in modern times, they have come to mean 'an ordinary matter' and 'a dead-end situation', respectively.

Also, key terms in Christianity such as ‘worship,’ ‘prayer,’ and ‘cathedral’ are examples of terms borrowed from Buddhism.

In this way, language has been constantly changing and settling in our daily lives under the influence of religion and culture.

Understand the meaning and usage of words properly

A dictionary of words that enriches our lives

_Speaking and writing become fun and your Korean language skills will improve naturally!

Each word has its own story.

Understanding the roots and context of words goes beyond simply memorizing vocabulary, allowing you to use the language more richly and effectively.

"There are no words without a story" provides an interesting look at the history and cultural background behind words, allowing us to look at everyday language from a new perspective.

The author says that while it is fun and important to know the etymology of words, there is no need to know Chinese characters or insist on old-fashioned speech.

Not knowing Chinese characters does not mean that you cannot understand the meaning of Chinese characters, and most people live well adapted to a language life in which more than half of their vocabulary is derived from Chinese characters.

I'm just saying that because I don't have Korean language skills.

So, what should we do to improve our Korean language skills? Rather than simply memorizing words, we need to experience the language in our daily lives.

By exploring the etymology of words, you can naturally learn their usage, and by reading various texts and writing them yourself, you can broaden your expressive power.

If we make good use of the subtlety and power of our language, writing deep sentences will not be that difficult.

As you do this, you will naturally gain confidence in conversation and writing, and your persuasiveness will increase.

This book is also useful for students who want to develop their thinking and expressive skills, working professionals who want to develop precise word choice and persuasiveness, and writers and creatives who want to strengthen their writing and storytelling skills.

It is also recommended for language enthusiasts who want to experience the fun and depth of language, and for those who want to improve their vocabulary and literacy in everyday life.

The ability to deeply understand and utilize language will serve as an excellent guide for establishing the quality and direction of life beyond simple communication.

“The vocabulary is so vast that it could easily be called a dictionary.” _Kim Cheol-ho, author of “Un-Da-Ri-Gwa-Da-Ri-Gwa”

“If you’re worried about your Korean language skills, I highly recommend reading this.” _Ahn Gwang-bok, philosophy teacher, author of “The Power of Writing One A4 Page”

“Where did that word come from?”

By capturing the subtle differences in vocabulary and using words appropriately,

The power of etymology to further enhance literacy, vocabulary, and expressiveness!

_Beyond linguistic literacy, to communication and empathy in life!

There are people who think they know Korean well and therefore don't need to study the language.

The language we use contains vocabulary, expressions, and cultural contexts that have been formed over a long period of time.

In particular, the Korean language has developed over a long history under the influence of various foreign words and Chinese characters.

The influence of Buddhism, which was introduced as a foreign religion, was deeply engraved in our language and must have had a great influence on the creation of Hangul.

Also, in modern times, the influence of Japan cannot be ignored.

The Japanese colonial period was a time when Japanese influence was at its peak, and after liberation, American culture and English language flooded in.

This 'infection' of language caused old words to be forgotten while at the same time creating new ones.

A few years ago, online, there was a heated debate over declining literacy, with comments like, “‘A boring apology’? I’m not bored at all,” “Does a three-day holiday mean four days off?” and “Does having high knowledge mean you have high level of knowledge?”

Misunderstandings and lack of empathy resulting from subtle differences in vocabulary or an inability to flexibly interpret the meaning of sentences have become a major topic of discussion across modern society, not just between generations.

The linguistic skills we must possess in modern times go beyond simply speaking and writing; they have become essential for enhancing empathy and communication skills and for gaining a deeper understanding of the world.

We can feel history, culture, and people's lives that we were unaware of through everyday words that we use without thinking.

Understanding how language has formed and changed empowers us to understand the meaning of words more deeply and use language more effectively.

Just as everything in the world has a beginning, the words we use also have a beginning if we trace them back.

The journey of exploring the essence of words is as fun as a tale from the past, as it involves finding traces of the past engraved in words.

It also helps you use vocabulary accurately because you can gain knowledge about words.

It is useful for improving literacy, vocabulary, and even expressive skills.

We learn, communicate, and live through knowledge, civilization, history, and literature through texts written in Korean.

Only when we know the etymology of a word can we understand its meaning more deeply and broaden our perspective on the world.

Etymology is a window into fully understanding the language we use and the world it creates.

With insight into the flow and relationships of the world

Developing the ability to understand and imagine the context of words

_History and culture, customs and social consciousness entangled in words

Author Jang In-yong, who has worked as a publisher for over 30 years and is now devoted to writing, lives a life inseparable from language.

The number of humanities and science books that passed through his hands is countless, and his outstanding linguistic sense and humanist perspective displayed in his books 『The Color of Hanja』, 『Zhou Dynasty and Joseon』, 『Food and Drink』, and his translation of 『History of Chinese Art』 have garnered attention from both academics and readers.

And that's not all.

In his youth, he was introduced to bronze inscriptions (characters carved or cast on bronzeware) and learned paleography. During his time at Deep-Rooted Tree, he was able to learn about the Korean language from CEO Han Chang-gi, who was called the “aesthetic genius of the Korean cultural world,” and thanks to this, he was able to create Professor Seo Jeong-su’s “Korean Grammar.”

That foundation would have been helpful in writing this book.

Author Jang In-yong went on a long journey for several years to find the stories behind words.

In his book, “Preface,” he stated:

“I’ve been writing all my life, and I’ve always had a casual interest in etymology, but I’ve never really delved into it.

I doubted whether I could write something like this, and as I began reading books and papers on etymology, I wondered whether I could write something different from existing etymology books.

“The conclusion is that I thought that if I covered a broader scope than the existing etymology, I could write an etymology book with my own unique personality.”

There is a lot of content in 『There is No Word Without a Story』 that is not covered in other etymology books.

For example, we looked at Chinese characters translated by Japan, such as 'danji (團地)' or 'gosubuji (高水敷地)' or 'economy' and 'society', and explored the process of language change and convergence through the stories contained in them.

This book also includes the origins of many words derived from Chinese characters that the author discovered while learning Chinese.

It also introduces the secrets behind the names of trees, fish, vegetables, and fruits, the origins of place names and religious terms, and interesting linguistic clues found in homonyms and consonants.

The author says that the reason for covering such a wide range of fields is because he hopes that readers will find a little more enjoyment in the Korean language through the hidden meanings in the words.

In particular, rather than focusing on explaining each word individually, this book helps you use words appropriately by linking them together and talking about them.

For example, wife, wife, housewife, and wife all refer to one person, but the author adds his or her opinion by clarifying that there are differences in context and nuance.

In this book, you can discover the hidden stories behind the words we use without thinking.

It carefully strips away the tangled history, culture, customs, and social consciousness of language.

It leads to the development of the power to understand and imagine the context of words, not through knowledge of individual phenomena, but through insight into the flow of the world and the relationships between them.

Part 1 deals with 'words that have changed meanings and are being used anew.'

It shows that language has constantly evolved to adapt to the times and environment through modern reinterpretations of words like 'economy,' 'society,' 'law,' and 'company,' combinations of foreign words and Chinese characters like 'can' and 'gangster,' and examples of Western concepts like 'democracy,' 'National Assembly,' and 'court.'

Part 2 is about 'words with reversed meanings'.

The adaptability and flexibility of language are explored through examples of positive meanings being changed to negative ones, such as 'sukmaek', 'yamche', and 'juchaek', and examples of expressions that should have opposite meanings being used with similar meanings, such as 'uyeonhi' and 'uyeonchange'.

It shows how language is given new meaning and evolves depending on the context in which it is used.

Part 3 introduces 'words that are more fun when you know their origins.'

It explores the connections between plants and animals, such as 'pheasant's leg' and 'mandrami', the origins of place names and bridges, such as 'baedari' and 'seopdari', the origins of fish names, such as 'squid', 'galchi' and 'myeongtae', the names and history of foods, such as 'kimchi' and 'kkakdugi', as well as the origins of colors, foreign crops, and trees.

Discover the history and culture contained in everyday words, and vividly convey the excitement and joy that language conveys.

Part 4 delves into 'words that cause confusion by being changed or distinguished into Chinese characters.'

This article deals with cases where emotional place names disappeared, with only administrative convenience remaining, such as 'Moraenae' changing to 'Sacheon' and 'Gajaegol' changing to 'Gajwadong'.

It also explores the impact of language change and the resulting breakdown in understanding through the confusion caused by Chinese character homonyms and the misunderstandings resulting from pronunciation diversity.

Part 5 deals with ‘Korean language and non-Korean language.’

It talks about the convergence and change of language through words that originated from Chinese characters but lost their original meanings through long-term use, such as '여하', '예시', '도대체', and '면'; new words that were created by combining Chinese characters and pure Korean words, such as '설소리하다', '호락호락', and '양치질'; and examples of foreign words transformed into Korean, such as '가방' and '구두'.

Part 6 explains the origins and accessibility of learning terms under the theme of “Words that make studying easier.”

In mathematics, the word 'function' (函數) originally comes from the Chinese character meaning 'box', but it is used without sufficient explanation and is perceived as difficult, whereas Korean expressions such as 'rhombus' and 'fan' are presented as positive examples that help understand the concept.

Furthermore, it provides an interesting historical background that made it inevitable for terms like "national language" (national language) and "science" (science) to be used, which were introduced through Japan, and emphasizes the importance of linguistic changes that increase the accessibility and efficiency of learning.

Part 7, titled 'Words Originating from Religion', shows that many of the words we use in our daily lives have their origins in religions such as Buddhism.

'Dabansa' originated from the fact that tea and rice were a daily occurrence in temples, and 'Ipansapan' originated from the distinction of roles among monks, but in modern times, they have come to mean 'an ordinary matter' and 'a dead-end situation', respectively.

Also, key terms in Christianity such as ‘worship,’ ‘prayer,’ and ‘cathedral’ are examples of terms borrowed from Buddhism.

In this way, language has been constantly changing and settling in our daily lives under the influence of religion and culture.

Understand the meaning and usage of words properly

A dictionary of words that enriches our lives

_Speaking and writing become fun and your Korean language skills will improve naturally!

Each word has its own story.

Understanding the roots and context of words goes beyond simply memorizing vocabulary, allowing you to use the language more richly and effectively.

"There are no words without a story" provides an interesting look at the history and cultural background behind words, allowing us to look at everyday language from a new perspective.

The author says that while it is fun and important to know the etymology of words, there is no need to know Chinese characters or insist on old-fashioned speech.

Not knowing Chinese characters does not mean that you cannot understand the meaning of Chinese characters, and most people live well adapted to a language life in which more than half of their vocabulary is derived from Chinese characters.

I'm just saying that because I don't have Korean language skills.

So, what should we do to improve our Korean language skills? Rather than simply memorizing words, we need to experience the language in our daily lives.

By exploring the etymology of words, you can naturally learn their usage, and by reading various texts and writing them yourself, you can broaden your expressive power.

If we make good use of the subtlety and power of our language, writing deep sentences will not be that difficult.

As you do this, you will naturally gain confidence in conversation and writing, and your persuasiveness will increase.

This book is also useful for students who want to develop their thinking and expressive skills, working professionals who want to develop precise word choice and persuasiveness, and writers and creatives who want to strengthen their writing and storytelling skills.

It is also recommended for language enthusiasts who want to experience the fun and depth of language, and for those who want to improve their vocabulary and literacy in everyday life.

The ability to deeply understand and utilize language will serve as an excellent guide for establishing the quality and direction of life beyond simple communication.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: February 28, 2025

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 332 pages | 476g | 135*200*26mm

- ISBN13: 9791192410487

- ISBN10: 1192410483

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)