Storyteller Essay

|

Description

Book Introduction

“The web of life that has been woven for thousands of years

“It’s disappearing everywhere”

A classic of our time that questions the origins of human life through the end of narrative art.

“This book depicts an era in which humans can no longer share their experiences with each other.

“Benjamin’s most tragic writing” _Hannah Arend

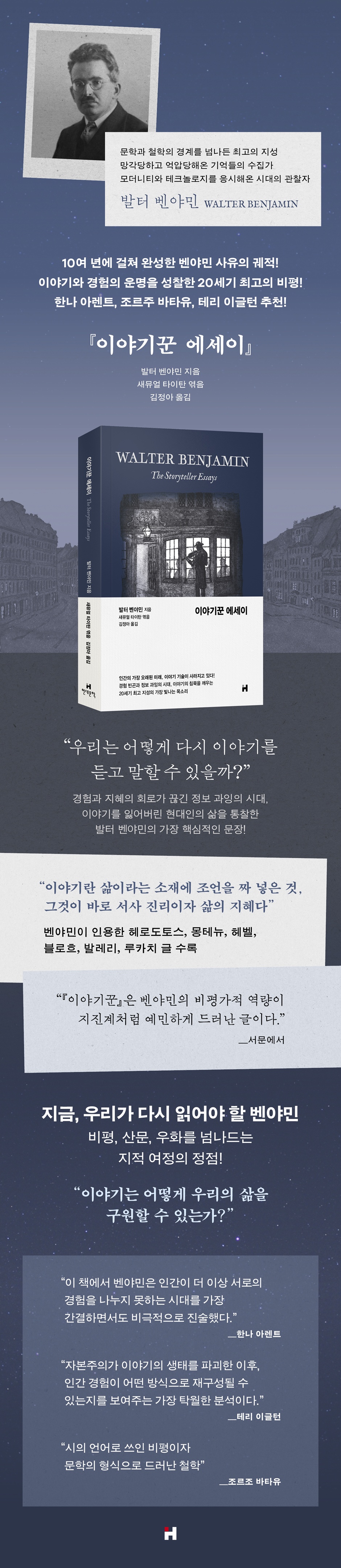

Today, Walter Benjamin, a philosopher who has had a great influence not only on academics such as philosophy, literature, aesthetics, and political science, but also on artists such as writers, directors, and musicians, has published "The Storyteller's Essay" in Modern Literature.

This book contains thirteen essays covering Benjamin's early, middle, and later criticisms, including "The Storyteller," Benjamin's representative work that sharply diagnoses the process of losing the power to tell stories amidst technology, industrialization, war, and modern changes, as well as "Johann Peter Hebel," "The Crisis of the Novel," "The Lisbon Earthquake," and "Experience and Lack."

In particular, this edition introduces Benjamin's original text in a new translation, while also restoring the trajectory of Benjamin's thought, showing how the axis of his thought, "the end of the storyteller and narrative art," was formed and evolved along the three axes of "experience, tradition, and oral tradition."

To delve deeper into the reasoning behind this, the writings of various thinkers and writers, including Herodotus, Montaigne, Hebel, Bloch, Valery, and Lukács, were included, allowing Benjamin's discussion to be more deeply understood within the long intellectual history surrounding narrative, experience, history, and literature.

Each essay in this book varies in length, type, and density, but they all converge on the same question: the end of storytelling.

Like Benyaman's diagnosis that "where stories disappear, information takes their place, and where experiences are cut off, only isolated individuals remain," he viewed the disappearance of storytelling not as a simple cultural phenomenon, but as the loss of the human ability to weave meaning into life.

However, this book is not merely Benjamin's 'eulogy' for the story.

He asks how storytelling can survive in an age of rapid change in labor, technology, and media, and proposes the aesthetics of the 'germination power' of words where advice and experience sprout again, the 'margin' of stories that avoid the immediacy of information and the compulsion for verification, and the 'boredom that lays the eggs of experience.'

In other words, it is a task of exploring the conditions under which stories can sprout again, even amid the awareness that “the web of life, woven for thousands of years, is unraveling everywhere.”

And this is the minimum critical practice that prevents all the rhetoric embellished with terms like "narrative," "storytelling," "content," and "narrative" from degenerating into empty buzzwords amidst the overabundance of data and information.

"The Storyteller's Essay" is a classic that makes us reflect on the power of stories and experiences that are still relevant in explaining our times.

“Narratives unrelated to the materiality of experience and works unrelated to the materiality of materials began to circulate as ‘images’ as if they were currency.

Looking back now, it was a tremendous foresight.

… … Terms like storytelling and narrative have become keywords that obscure issues in the vocabulary of corporate branding and political propaganda, and the path to realizing that our modern lives have lost their stories due to the overflow of information and the proliferation of algorithms has become even more distant.

… … In that sense, Benjamin’s writing seems somewhat similar to the needlework of Marie Monnier, who lived in the same era as him.

“It is because of this timeless approach that the essayist Benjamin feels like a descendant of the unique storyteller Leskov.” - From the “Preface”

“It’s disappearing everywhere”

A classic of our time that questions the origins of human life through the end of narrative art.

“This book depicts an era in which humans can no longer share their experiences with each other.

“Benjamin’s most tragic writing” _Hannah Arend

Today, Walter Benjamin, a philosopher who has had a great influence not only on academics such as philosophy, literature, aesthetics, and political science, but also on artists such as writers, directors, and musicians, has published "The Storyteller's Essay" in Modern Literature.

This book contains thirteen essays covering Benjamin's early, middle, and later criticisms, including "The Storyteller," Benjamin's representative work that sharply diagnoses the process of losing the power to tell stories amidst technology, industrialization, war, and modern changes, as well as "Johann Peter Hebel," "The Crisis of the Novel," "The Lisbon Earthquake," and "Experience and Lack."

In particular, this edition introduces Benjamin's original text in a new translation, while also restoring the trajectory of Benjamin's thought, showing how the axis of his thought, "the end of the storyteller and narrative art," was formed and evolved along the three axes of "experience, tradition, and oral tradition."

To delve deeper into the reasoning behind this, the writings of various thinkers and writers, including Herodotus, Montaigne, Hebel, Bloch, Valery, and Lukács, were included, allowing Benjamin's discussion to be more deeply understood within the long intellectual history surrounding narrative, experience, history, and literature.

Each essay in this book varies in length, type, and density, but they all converge on the same question: the end of storytelling.

Like Benyaman's diagnosis that "where stories disappear, information takes their place, and where experiences are cut off, only isolated individuals remain," he viewed the disappearance of storytelling not as a simple cultural phenomenon, but as the loss of the human ability to weave meaning into life.

However, this book is not merely Benjamin's 'eulogy' for the story.

He asks how storytelling can survive in an age of rapid change in labor, technology, and media, and proposes the aesthetics of the 'germination power' of words where advice and experience sprout again, the 'margin' of stories that avoid the immediacy of information and the compulsion for verification, and the 'boredom that lays the eggs of experience.'

In other words, it is a task of exploring the conditions under which stories can sprout again, even amid the awareness that “the web of life, woven for thousands of years, is unraveling everywhere.”

And this is the minimum critical practice that prevents all the rhetoric embellished with terms like "narrative," "storytelling," "content," and "narrative" from degenerating into empty buzzwords amidst the overabundance of data and information.

"The Storyteller's Essay" is a classic that makes us reflect on the power of stories and experiences that are still relevant in explaining our times.

“Narratives unrelated to the materiality of experience and works unrelated to the materiality of materials began to circulate as ‘images’ as if they were currency.

Looking back now, it was a tremendous foresight.

… … Terms like storytelling and narrative have become keywords that obscure issues in the vocabulary of corporate branding and political propaganda, and the path to realizing that our modern lives have lost their stories due to the overflow of information and the proliferation of algorithms has become even more distant.

… … In that sense, Benjamin’s writing seems somewhat similar to the needlework of Marie Monnier, who lived in the same era as him.

“It is because of this timeless approach that the essayist Benjamin feels like a descendant of the unique storyteller Leskov.” - From the “Preface”

index

Introductionㆍ7

Storyteller Essay

Johann Peter Hebel, 35

The Crisis of the Novel: On Döblin's Berlin Alexanderplatzㆍ48

Raspberry Omeletteㆍ62

Lisbon earthquake 65

Oscar Maria Graf: Storytellerㆍ77

About Proverbsㆍ83

Handkerchiefㆍ85

Stories and Healingㆍ94

Reading Novelsㆍ96

Storytelling Skillsㆍ98

From the Fireplace: Celebrating the 25th Anniversary of a Novelㆍ102

Experience and Deficiencyㆍ112

The Storyteller: Reflections on the Works of Nikolai Leskovㆍ124

Writings by other authors

Silence and the Mirror, Ernst Bloch, 177

Giants' Toys: A Heroic Tale by Ernst Bloch, 182

Marie Monnier's Handicrafts by Paul Valéry, 194

Georg Lukács, from Theory of the Novel, 197

On Sorrow by Michel de Montaigne, 210

Herodotus, from "History," 219

From "The Treasure Chest: A Friend for the Whole Family" by Johann Peter Hebel, 223

Text source: 234

Searchㆍ236

Storyteller Essay

Johann Peter Hebel, 35

The Crisis of the Novel: On Döblin's Berlin Alexanderplatzㆍ48

Raspberry Omeletteㆍ62

Lisbon earthquake 65

Oscar Maria Graf: Storytellerㆍ77

About Proverbsㆍ83

Handkerchiefㆍ85

Stories and Healingㆍ94

Reading Novelsㆍ96

Storytelling Skillsㆍ98

From the Fireplace: Celebrating the 25th Anniversary of a Novelㆍ102

Experience and Deficiencyㆍ112

The Storyteller: Reflections on the Works of Nikolai Leskovㆍ124

Writings by other authors

Silence and the Mirror, Ernst Bloch, 177

Giants' Toys: A Heroic Tale by Ernst Bloch, 182

Marie Monnier's Handicrafts by Paul Valéry, 194

Georg Lukács, from Theory of the Novel, 197

On Sorrow by Michel de Montaigne, 210

Herodotus, from "History," 219

From "The Treasure Chest: A Friend for the Whole Family" by Johann Peter Hebel, 223

Text source: 234

Searchㆍ236

Detailed image

Into the book

There is something called the fate of books.

There may also be something called the fate of essays.

In any case, the fate of "The Storyteller" is a good example of how surprising the path a piece of writing can take.

That it was written by a German Jew who was trying to make a living in exile after the Nazis took over Germany in 1933; that it claimed to discuss a brilliant but little-read Russian writer, but then kept straying into other topics; that the peculiar Swiss magazine that published it closed down in 1937 with its last issue, which had only 35 subscribers; and that the author of the piece took his own life three years later while escaping Nazi-occupied France, leaving behind a vast body of unfinished critical work and a vast manuscript.

None of this seems like the stuff of success stories, yet Walter Benjamin's "The Storyteller" is now one of the most famous literary essays of the 20th century.

It is a well-known text among literary scholars, and is often recommended as reading material in fields such as anthropology, media studies, and creative writing.

It's a surprising twist of fate, considering that this article received no attention when it first came out.

--- p.9~10

Historians deal with “world history,” while almanac compilers deal with everything in the world.

The historian is interested in the web of events, the infinite intertwining of causes and effects, but even if he puts together all that he has learned or discovered, it is only one small knot in that web.

On the other hand, the compiler of the almanac is interested in the small events that occur within the narrow radius of the city or region in which he lives, but to him, those small events are not just one of the small elements that make up the larger whole, but rather something more important than the larger whole.

Because a true almanac compiler writes a fable of all things in the world while writing the almanac.

The local history and world affairs written by the yearbook compiler reflect the long-standing interplay between the microcosm and the macrocosm.

--- p.41

We've all been to the pharmacy and watched, waiting in line, as medications are prepared according to prescriptions, right? The pharmacist places all the ingredients and particles on extremely precise scales, weighing them out 1 gram at a time, 0.1 gram at a time, and then prepares the medication.

I think I become that kind of pharmacist when I talk about things on the radio like this.

I put the story time on the scale by 1 minute and adjust the story in precise proportions, such as how many minutes for this content and how many minutes for that content.

You may ask:

"Huh? Why? If you want to talk about the Lisbon earthquake, why don't you start with how it started? Then you can go on to tell what happened after the earthquake?" But I don't think that's fun.

House after house collapses, family after family loses their lives, the horror of the spreading fires, the horror of the tsunami, the darkness, the looting, the tragedy of the injured, the cries of those searching for the missing… No one wants to hear stories like this, stories that are just like this.

This kind of stuff is pretty much the same in every story about a major natural disaster.

--- p.65~66

As I gazed at the Barcelona scenery from the Bellverho, I thought of Captain O, with whom I had said goodbye just a few hours before.

He was the first storyteller I ever met in my life, and as I said before, the art of storytelling is disappearing, so he will probably be the last storyteller I ever meet in my life.

Only when I recalled those seemingly endless hours, when he would pace the quarterdeck, often casting his gaze into the distance, did I understand why the art of storytelling was fading away.

I've found that people who don't get bored can't be storytellers.

But boredom is disappearing from our lives.

Behaviors that are secretly and intimately linked to boredom are disappearing.

--- p.86

We already know about the healing power of stories thanks to the existence of the Merseburg Book of Magic.

This book of magic not only copies Odin's spells, but also tells us under what circumstances Odin came to use such words as spells in the first place.

We also know that what patients tell their doctors early in their treatment can be the beginning of the healing process.

This raises a question:

Couldn't stories, in many cases, create the right environment and conditions for healing? If only we could allow illness to flow down the river of story, if only we could allow it to flow along a long enough river to its mouth, wouldn't any illness be cured?

--- p.94~95

The reason readers are drawn to novels again and again is because of the novel's most mysterious gift.

A novel is something that warms a shiveringly cold life with the fire of death.

--- p.111

Because the value of experience has fallen to the ground.

As you can see, it is falling lower and lower.

Every time I read the newspaper, it is proven that the value of experience has once again hit rock bottom, that not only the landscape of the outside world but even the landscape of the human world has changed overnight to an extent I never imagined possible.

… … It was the first time that the experience was so fundamentally exposed as a lie.

The experience in the strategic sphere was exposed as false by the war of attrition, the experience in the economic sphere was exposed as false by inflation, the experience in the physical sphere was exposed as false by the war of quantities, and the experience in the human sphere was exposed as false by those in power.

When the generation that went to school by horse-drawn carriage stood under the sky, the only things that remained the same in that landscape were the clouds floating in the sky and the small, weak human bodies standing in the field of destructive, sweeping, and crushing power.

--- p.125~126

The reason storytelling is disappearing is because the epic aspect of truth, that is, wisdom, is disappearing.

The process of storytelling's downfall began early with secularization.

Nothing could be more foolish than to see this as simply a “manifestation of decline,” let alone a “modern” manifestation of decline.

This process, which is merely a byproduct of the development of productive forces in the history of secular society, gradually drives storytellers out of the living field of language, while at the same time allowing us to perceive a new beauty in its disappearance.

--- p.131

The best way to encourage people to remember a story longer is to avoid psychoanalyzing it and to tell it concisely, without explaining it.

The more naturally the storyteller succeeds in refraining from psychological explanations, the more likely it is that the listener will give the story a place in their memory, the more fully the story will be absorbed into their experience, and the more strongly they will want to tell it again to someone else soon.

This process of absorption, which takes place deeply in the listener's mind and body, requires a state of relaxation, which opportunities to be in that state are becoming increasingly rare.

If sleep is the pinnacle of physical relaxation, boredom is the pinnacle of mental relaxation.

A dreaming bird called boredom hatches an egg called experience.

--- p.139

Isn't the storyteller's relationship with his material—life itself—a manual process? Isn't the storyteller's task to process the raw material of experience into a unique, durable, and useful way? If proverbs are the hieroglyphics of storytelling, then they seem to best demonstrate the kind of processing that goes into it.

Well, then, I guess we could say this.

Proverbs are the ruins of things that happened in the past, and from them ethics grow, clinging to attitudes like ivy to a wall.

In this way, storytellers belong to the category of teachers and wise men.

--- p.172

Some of the most precious things only arise in the rarest of circumstances when the right conditions coincide.

Diamonds, happiness, and very pure emotions are such things.

But some of them are created through the accumulation of countless insignificant events and essential supports.

It takes a very long time, and it takes peace as much as it takes time.

Fine pearls, ripe wines with a deep flavor, and fully mature personalities are reminiscent of the slow accumulation of similar benefits that are constantly being given.

The process of building excellence continues until perfection is reached.

There may also be something called the fate of essays.

In any case, the fate of "The Storyteller" is a good example of how surprising the path a piece of writing can take.

That it was written by a German Jew who was trying to make a living in exile after the Nazis took over Germany in 1933; that it claimed to discuss a brilliant but little-read Russian writer, but then kept straying into other topics; that the peculiar Swiss magazine that published it closed down in 1937 with its last issue, which had only 35 subscribers; and that the author of the piece took his own life three years later while escaping Nazi-occupied France, leaving behind a vast body of unfinished critical work and a vast manuscript.

None of this seems like the stuff of success stories, yet Walter Benjamin's "The Storyteller" is now one of the most famous literary essays of the 20th century.

It is a well-known text among literary scholars, and is often recommended as reading material in fields such as anthropology, media studies, and creative writing.

It's a surprising twist of fate, considering that this article received no attention when it first came out.

--- p.9~10

Historians deal with “world history,” while almanac compilers deal with everything in the world.

The historian is interested in the web of events, the infinite intertwining of causes and effects, but even if he puts together all that he has learned or discovered, it is only one small knot in that web.

On the other hand, the compiler of the almanac is interested in the small events that occur within the narrow radius of the city or region in which he lives, but to him, those small events are not just one of the small elements that make up the larger whole, but rather something more important than the larger whole.

Because a true almanac compiler writes a fable of all things in the world while writing the almanac.

The local history and world affairs written by the yearbook compiler reflect the long-standing interplay between the microcosm and the macrocosm.

--- p.41

We've all been to the pharmacy and watched, waiting in line, as medications are prepared according to prescriptions, right? The pharmacist places all the ingredients and particles on extremely precise scales, weighing them out 1 gram at a time, 0.1 gram at a time, and then prepares the medication.

I think I become that kind of pharmacist when I talk about things on the radio like this.

I put the story time on the scale by 1 minute and adjust the story in precise proportions, such as how many minutes for this content and how many minutes for that content.

You may ask:

"Huh? Why? If you want to talk about the Lisbon earthquake, why don't you start with how it started? Then you can go on to tell what happened after the earthquake?" But I don't think that's fun.

House after house collapses, family after family loses their lives, the horror of the spreading fires, the horror of the tsunami, the darkness, the looting, the tragedy of the injured, the cries of those searching for the missing… No one wants to hear stories like this, stories that are just like this.

This kind of stuff is pretty much the same in every story about a major natural disaster.

--- p.65~66

As I gazed at the Barcelona scenery from the Bellverho, I thought of Captain O, with whom I had said goodbye just a few hours before.

He was the first storyteller I ever met in my life, and as I said before, the art of storytelling is disappearing, so he will probably be the last storyteller I ever meet in my life.

Only when I recalled those seemingly endless hours, when he would pace the quarterdeck, often casting his gaze into the distance, did I understand why the art of storytelling was fading away.

I've found that people who don't get bored can't be storytellers.

But boredom is disappearing from our lives.

Behaviors that are secretly and intimately linked to boredom are disappearing.

--- p.86

We already know about the healing power of stories thanks to the existence of the Merseburg Book of Magic.

This book of magic not only copies Odin's spells, but also tells us under what circumstances Odin came to use such words as spells in the first place.

We also know that what patients tell their doctors early in their treatment can be the beginning of the healing process.

This raises a question:

Couldn't stories, in many cases, create the right environment and conditions for healing? If only we could allow illness to flow down the river of story, if only we could allow it to flow along a long enough river to its mouth, wouldn't any illness be cured?

--- p.94~95

The reason readers are drawn to novels again and again is because of the novel's most mysterious gift.

A novel is something that warms a shiveringly cold life with the fire of death.

--- p.111

Because the value of experience has fallen to the ground.

As you can see, it is falling lower and lower.

Every time I read the newspaper, it is proven that the value of experience has once again hit rock bottom, that not only the landscape of the outside world but even the landscape of the human world has changed overnight to an extent I never imagined possible.

… … It was the first time that the experience was so fundamentally exposed as a lie.

The experience in the strategic sphere was exposed as false by the war of attrition, the experience in the economic sphere was exposed as false by inflation, the experience in the physical sphere was exposed as false by the war of quantities, and the experience in the human sphere was exposed as false by those in power.

When the generation that went to school by horse-drawn carriage stood under the sky, the only things that remained the same in that landscape were the clouds floating in the sky and the small, weak human bodies standing in the field of destructive, sweeping, and crushing power.

--- p.125~126

The reason storytelling is disappearing is because the epic aspect of truth, that is, wisdom, is disappearing.

The process of storytelling's downfall began early with secularization.

Nothing could be more foolish than to see this as simply a “manifestation of decline,” let alone a “modern” manifestation of decline.

This process, which is merely a byproduct of the development of productive forces in the history of secular society, gradually drives storytellers out of the living field of language, while at the same time allowing us to perceive a new beauty in its disappearance.

--- p.131

The best way to encourage people to remember a story longer is to avoid psychoanalyzing it and to tell it concisely, without explaining it.

The more naturally the storyteller succeeds in refraining from psychological explanations, the more likely it is that the listener will give the story a place in their memory, the more fully the story will be absorbed into their experience, and the more strongly they will want to tell it again to someone else soon.

This process of absorption, which takes place deeply in the listener's mind and body, requires a state of relaxation, which opportunities to be in that state are becoming increasingly rare.

If sleep is the pinnacle of physical relaxation, boredom is the pinnacle of mental relaxation.

A dreaming bird called boredom hatches an egg called experience.

--- p.139

Isn't the storyteller's relationship with his material—life itself—a manual process? Isn't the storyteller's task to process the raw material of experience into a unique, durable, and useful way? If proverbs are the hieroglyphics of storytelling, then they seem to best demonstrate the kind of processing that goes into it.

Well, then, I guess we could say this.

Proverbs are the ruins of things that happened in the past, and from them ethics grow, clinging to attitudes like ivy to a wall.

In this way, storytellers belong to the category of teachers and wise men.

--- p.172

Some of the most precious things only arise in the rarest of circumstances when the right conditions coincide.

Diamonds, happiness, and very pure emotions are such things.

But some of them are created through the accumulation of countless insignificant events and essential supports.

It takes a very long time, and it takes peace as much as it takes time.

Fine pearls, ripe wines with a deep flavor, and fully mature personalities are reminiscent of the slow accumulation of similar benefits that are constantly being given.

The process of building excellence continues until perfection is reached.

--- p.194

Publisher's Review

『Storyteller Essay』, spanning over 10 years

A crystallization of intense thought and a collage of diverse attempts

"The Storyteller" remains one of Benjamin's most frequently cited works, a text in which his "critical capacity is as acutely revealed as a seismograph." It stands at the heart of his oeuvre, alongside "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction" and "On Some Motives in Baudelaire."

"The Storyteller" is the result of a long period of thought that began during Benjamin's Berlin student days and gained momentum in the late 1920s. The concepts, images, and arguments he tested in various writings, including essays, newspaper articles, book reviews, and short stories published between 1926 and 1936, are finally condensed into this work.

By combining these essays with "The Storyteller," "The Storyteller Essays" aims to more clearly reveal how Benjamin's thoughts developed.

In "Johann Peter Hebel" (1926), he foreshadowed the distinction between storytellers and information providers, saying, "The historian deals with world history, while the almanac compiler deals with everything in the world." Following this, in "Lisbon Earthquake" (1931), a collection of radio lectures, he conveyed the disaster through the voice of a storyteller, expanding the disaster of a city into the ripple effect of world history, and experimenting with the connection between experience, tradition, and narrative within the medium of radio.

In "The Handkerchief" (1932), Benjamin's narrative experimentation reaches its climax by embodying the oral form of a real storyteller.

Next, in “Experience and Lack” (1933), he analyzes how technological civilization and war have destroyed human experience and tradition, and raises the issue of “loss of experience” and “new beginning,” which are the core themes of Benjamin’s thought.

In this way, different forms of text echo each other, and ultimately, in “The Storyteller” (1936), all the pieces combine into a single collage.

In this way, this book conveys the narrative process that Benjamin himself had to go through in order to talk about "the end of the art of storytelling." One of the important meanings of this book is that it allows us to glimpse how each piece resonates with his larger themes and the dynamics of Benjamin's writing.

“A story is advice woven into the material of life,

That is the narrative truth and the wisdom of life.”

Benjamin's "The Storyteller" begins with a lament over the "decline of the storyteller."

“For us, the storyteller is already a distant being and is becoming increasingly distant.

… … We confirm that fact almost every day.

It's as if someone had stolen our safest asset: the ability to share experiences." The silence left by the storyteller's absence was replaced by the language of information.

In the endless stream of events and their countless explanations, information is overloaded.

“Every morning we come across news articles from all over the world.

But it's rare that we come across such unique cases.

“Because every incident we encounter is armed with an explanation from beginning to end.”

Benjamin draws on an anecdote from Herodotus's Histories to show that stories flourish when they are left unexplained.

“Psamenidu, king of Egypt, was defeated by Cambyses, king of Persia, and taken prisoner.

When he saw his daughter, who had also been taken prisoner, fetching water in the form of a servant girl, he just stared blankly at the ground.

Even when he saw his son being dragged to the execution ground, he remained expressionless.

But when he saw one of his servants being taken prisoner, he struck his head with his hand and began to weep. Why did he do that?

According to Benjamin, Herodotus does not explain why.

This historical episode remains a subject of much debate, but the very fact that it has retained its relevance for so long, unlike information that becomes obsolete over time, lies precisely in its lack of explanation.

It is like “a grain of wheat that has not lost its germination power for thousands of years in the airtight, sealed space of a pyramid.”

The story contains 'mystery'.

It does not flow in just one direction, and has multiple meanings at the same time.

Each time it is transmitted, the details change and it is rewritten anew.

In this way, the experiences that become the basis of stories are experiences that are passed down from mouth to mouth.

This experience is the fountain of stories from which all storytellers draw their stories, a collective experience passed down from generation to generation.

In this respect, the story is a kind of 'narrative of wisdom', and the storyteller is a 'mediator of the communal experience of life' and an 'advisor' on the way and attitude to lead life.

Benjamin described the way of conveying experience as “a craft form of transmission,” “an act secretly linked to boredom,” and “an authority that gives it legitimacy even when it is unverified.” In this context, the art of storytelling is connected to “craftsmanship.”

Although industrialization, war, and media changes are eroding the ecology of community and storytelling, can't those skills be revived when head and hand meet again?

In an age where the circuit of experience and wisdom is broken,

In what form and attitude will we speak again?

Today we are in the midst of the world Benjamin foresaw.

We are already accustomed to searching for summaries on YouTube (and even at high speed) instead of reading books or watching dramas, and to exchanging messages only through text instead of talking face to face or hearing voices.

The power to share experiences and pass on community memories has disappeared in this consumerist and instrumental context, and the storytellers who mediate community wisdom and experience have been reduced to dopamine slaves in an accelerated society.

It is said that stories live on from mouth to mouth.

According to Benjamin, for such a story to sprout, a time of 'boredom', a pause that arises outside the time of capital, is necessary.

“As the dreaming bird of boredom hatches the egg of experience,” stories spring from the still spring of time.

It feels like a distant thing to us, who have no leisure in life and have lost the ability to endure boredom.

However, Benjamin emphasizes that stories have the power to heal, just as a patient telling a story to a doctor is the first step in treatment.

“If only we could let the disease float down the river of stories, if only we could make it flow along a long enough river to its mouth, wouldn’t any illness be cured?” In this context, the book poses a question that remains alive for today’s readers.

How can we re-share experiences? How can stories save our lives? This is why this book isn't simply a nostalgia for the past, but a call to find a new language of experience that will enable future communities.

A crystallization of intense thought and a collage of diverse attempts

"The Storyteller" remains one of Benjamin's most frequently cited works, a text in which his "critical capacity is as acutely revealed as a seismograph." It stands at the heart of his oeuvre, alongside "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction" and "On Some Motives in Baudelaire."

"The Storyteller" is the result of a long period of thought that began during Benjamin's Berlin student days and gained momentum in the late 1920s. The concepts, images, and arguments he tested in various writings, including essays, newspaper articles, book reviews, and short stories published between 1926 and 1936, are finally condensed into this work.

By combining these essays with "The Storyteller," "The Storyteller Essays" aims to more clearly reveal how Benjamin's thoughts developed.

In "Johann Peter Hebel" (1926), he foreshadowed the distinction between storytellers and information providers, saying, "The historian deals with world history, while the almanac compiler deals with everything in the world." Following this, in "Lisbon Earthquake" (1931), a collection of radio lectures, he conveyed the disaster through the voice of a storyteller, expanding the disaster of a city into the ripple effect of world history, and experimenting with the connection between experience, tradition, and narrative within the medium of radio.

In "The Handkerchief" (1932), Benjamin's narrative experimentation reaches its climax by embodying the oral form of a real storyteller.

Next, in “Experience and Lack” (1933), he analyzes how technological civilization and war have destroyed human experience and tradition, and raises the issue of “loss of experience” and “new beginning,” which are the core themes of Benjamin’s thought.

In this way, different forms of text echo each other, and ultimately, in “The Storyteller” (1936), all the pieces combine into a single collage.

In this way, this book conveys the narrative process that Benjamin himself had to go through in order to talk about "the end of the art of storytelling." One of the important meanings of this book is that it allows us to glimpse how each piece resonates with his larger themes and the dynamics of Benjamin's writing.

“A story is advice woven into the material of life,

That is the narrative truth and the wisdom of life.”

Benjamin's "The Storyteller" begins with a lament over the "decline of the storyteller."

“For us, the storyteller is already a distant being and is becoming increasingly distant.

… … We confirm that fact almost every day.

It's as if someone had stolen our safest asset: the ability to share experiences." The silence left by the storyteller's absence was replaced by the language of information.

In the endless stream of events and their countless explanations, information is overloaded.

“Every morning we come across news articles from all over the world.

But it's rare that we come across such unique cases.

“Because every incident we encounter is armed with an explanation from beginning to end.”

Benjamin draws on an anecdote from Herodotus's Histories to show that stories flourish when they are left unexplained.

“Psamenidu, king of Egypt, was defeated by Cambyses, king of Persia, and taken prisoner.

When he saw his daughter, who had also been taken prisoner, fetching water in the form of a servant girl, he just stared blankly at the ground.

Even when he saw his son being dragged to the execution ground, he remained expressionless.

But when he saw one of his servants being taken prisoner, he struck his head with his hand and began to weep. Why did he do that?

According to Benjamin, Herodotus does not explain why.

This historical episode remains a subject of much debate, but the very fact that it has retained its relevance for so long, unlike information that becomes obsolete over time, lies precisely in its lack of explanation.

It is like “a grain of wheat that has not lost its germination power for thousands of years in the airtight, sealed space of a pyramid.”

The story contains 'mystery'.

It does not flow in just one direction, and has multiple meanings at the same time.

Each time it is transmitted, the details change and it is rewritten anew.

In this way, the experiences that become the basis of stories are experiences that are passed down from mouth to mouth.

This experience is the fountain of stories from which all storytellers draw their stories, a collective experience passed down from generation to generation.

In this respect, the story is a kind of 'narrative of wisdom', and the storyteller is a 'mediator of the communal experience of life' and an 'advisor' on the way and attitude to lead life.

Benjamin described the way of conveying experience as “a craft form of transmission,” “an act secretly linked to boredom,” and “an authority that gives it legitimacy even when it is unverified.” In this context, the art of storytelling is connected to “craftsmanship.”

Although industrialization, war, and media changes are eroding the ecology of community and storytelling, can't those skills be revived when head and hand meet again?

In an age where the circuit of experience and wisdom is broken,

In what form and attitude will we speak again?

Today we are in the midst of the world Benjamin foresaw.

We are already accustomed to searching for summaries on YouTube (and even at high speed) instead of reading books or watching dramas, and to exchanging messages only through text instead of talking face to face or hearing voices.

The power to share experiences and pass on community memories has disappeared in this consumerist and instrumental context, and the storytellers who mediate community wisdom and experience have been reduced to dopamine slaves in an accelerated society.

It is said that stories live on from mouth to mouth.

According to Benjamin, for such a story to sprout, a time of 'boredom', a pause that arises outside the time of capital, is necessary.

“As the dreaming bird of boredom hatches the egg of experience,” stories spring from the still spring of time.

It feels like a distant thing to us, who have no leisure in life and have lost the ability to endure boredom.

However, Benjamin emphasizes that stories have the power to heal, just as a patient telling a story to a doctor is the first step in treatment.

“If only we could let the disease float down the river of stories, if only we could make it flow along a long enough river to its mouth, wouldn’t any illness be cured?” In this context, the book poses a question that remains alive for today’s readers.

How can we re-share experiences? How can stories save our lives? This is why this book isn't simply a nostalgia for the past, but a call to find a new language of experience that will enable future communities.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: October 25, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 242 pages | 280g | 128*188*16mm

- ISBN13: 9791167903280

- ISBN10: 1167903285

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)