How to Become Enlightened in One Shot: A Revolution in the Mind

|

Description

Book Introduction

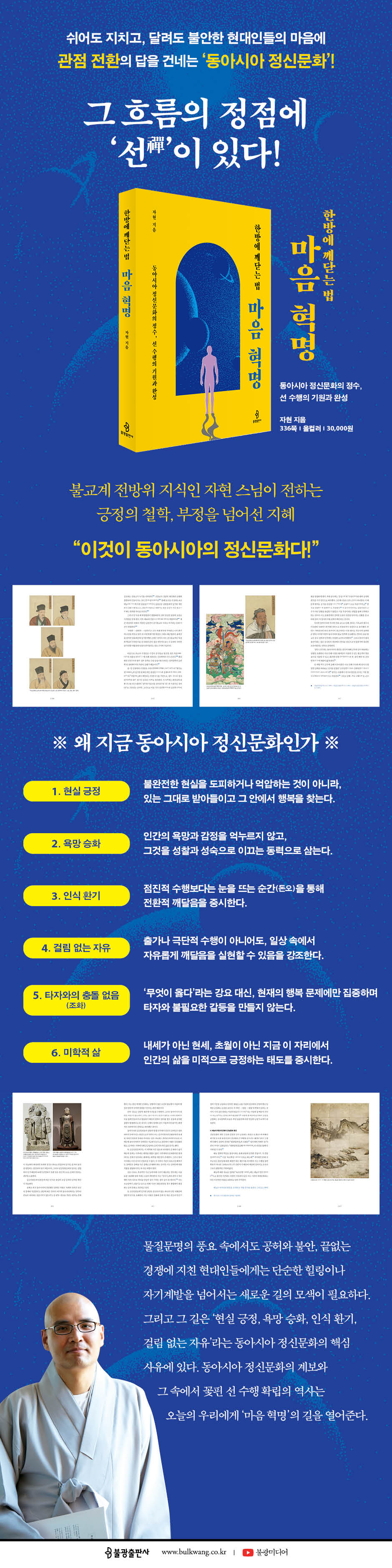

In the hearts of modern people who feel tired even when resting and anxious even when running

'East Asian spiritual culture' that offers the answer of 'positivity' and 'transformation'!

At the peak of that flow is ‘Zen’!

Even amidst the abundance of material civilization, modern people, weary of emptiness, anxiety, and endless competition, need to find a new path that goes beyond simple healing or self-improvement.

The new book, “How to Achieve Enlightenment in One Shot: A Revolution in the Mind,” by Buddhist scholar and all-rounder Monk Ja-Hyeon, provides the answer.

This book centers on the core ideas of East Asian spiritual culture: "affirmation of reality, sublimation of desire, awakening of awareness, and unhindered freedom," and emphasizes the power of "a shift in perspective" that can transform one's entire life.

In particular, based on the monistic worldview that can be said to be the foundation of East Asian spiritual culture, it follows the flow of changes in East Asian spiritual culture, such as the Confucian and Taoist ideas represented by Confucius and Laozi, the introduction of Buddhism and the fusion of the Northern and Southern Dynasties of Wei and Jin, the Don-o of Huineng in the Tang Dynasty, and the daily practice theory of Dayue Zonggu in the Song Dynasty, and shows how such thinking was completed as the tradition of Zen practice, a practice that is not separated from life but already evokes a complete nature.

The genealogy of East Asian spiritual culture and the history of the establishment of Zen practice that blossomed within it open the way for a revolution of the mind for us today.

'East Asian spiritual culture' that offers the answer of 'positivity' and 'transformation'!

At the peak of that flow is ‘Zen’!

Even amidst the abundance of material civilization, modern people, weary of emptiness, anxiety, and endless competition, need to find a new path that goes beyond simple healing or self-improvement.

The new book, “How to Achieve Enlightenment in One Shot: A Revolution in the Mind,” by Buddhist scholar and all-rounder Monk Ja-Hyeon, provides the answer.

This book centers on the core ideas of East Asian spiritual culture: "affirmation of reality, sublimation of desire, awakening of awareness, and unhindered freedom," and emphasizes the power of "a shift in perspective" that can transform one's entire life.

In particular, based on the monistic worldview that can be said to be the foundation of East Asian spiritual culture, it follows the flow of changes in East Asian spiritual culture, such as the Confucian and Taoist ideas represented by Confucius and Laozi, the introduction of Buddhism and the fusion of the Northern and Southern Dynasties of Wei and Jin, the Don-o of Huineng in the Tang Dynasty, and the daily practice theory of Dayue Zonggu in the Song Dynasty, and shows how such thinking was completed as the tradition of Zen practice, a practice that is not separated from life but already evokes a complete nature.

The genealogy of East Asian spiritual culture and the history of the establishment of Zen practice that blossomed within it open the way for a revolution of the mind for us today.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Introduction | Speaking of the Spiritual Revolution in East Asia

Ⅰ.

What's the problem

1.

Research Purpose

2.

Characteristics and Previous Research on East Asian Meditation

Ⅱ.

Monism, the external foundation of East Asian meditation

1.

Monism centered on the monarchy and the structure of the orthodox church

1) Changes in the relationship and status between the king and the subjects

2) The theory of the inner and outer kings and the sage monarch

2.

Mind-body monism and the theory of the correspondence of heaven and man

1) The monism of mind and body and the existence of life and death

2) The theory of the correspondence between heaven and man and the status of humans

Ⅲ.

The theory of mind and spirit, the inner center of East Asian meditation

1.

The rise of the theory of mind in Chinese philosophy and the recovery of mind

1) The background of one's nature and its relationship with heaven

2) The legitimacy of Mencius' theory of human nature as good and the theory of self-cultivation

2.

The purpose of accepting and practicing the theory of mind in Chinese Buddhism

1) The spread of Buddhism to China and the establishment of the idea of Buddha nature

2) The practice and purpose of Chinese philosophy

(1) Characteristics and Purpose of Chinese Buddhist Practice Theory

(2) Characteristics and Purpose of Neo-Confucianism’s Theory of Self-cultivation

Ⅳ.

Reviewing the Characteristics of East Asian Meditation

1.

Accepting reality and embracing change

1) Supernatural powers and overcoming death

2) Acceptance of change and idealism

2.

Theory of Dance Practice and Practice Methods of Zen and Zen Buddhism

1) Theory of Original Perfection and Uselessness of Practice

2) The structure of the entire completion and the world of the world

3.

Idealism and human existence

1) Idealism and aesthetic judgment

2) Philosophy of change and existential solutions

V.

Bringing the curtain down on the grand finale

supplement.

Unfinished problems and romantic life

main

References

Ⅰ.

What's the problem

1.

Research Purpose

2.

Characteristics and Previous Research on East Asian Meditation

Ⅱ.

Monism, the external foundation of East Asian meditation

1.

Monism centered on the monarchy and the structure of the orthodox church

1) Changes in the relationship and status between the king and the subjects

2) The theory of the inner and outer kings and the sage monarch

2.

Mind-body monism and the theory of the correspondence of heaven and man

1) The monism of mind and body and the existence of life and death

2) The theory of the correspondence between heaven and man and the status of humans

Ⅲ.

The theory of mind and spirit, the inner center of East Asian meditation

1.

The rise of the theory of mind in Chinese philosophy and the recovery of mind

1) The background of one's nature and its relationship with heaven

2) The legitimacy of Mencius' theory of human nature as good and the theory of self-cultivation

2.

The purpose of accepting and practicing the theory of mind in Chinese Buddhism

1) The spread of Buddhism to China and the establishment of the idea of Buddha nature

2) The practice and purpose of Chinese philosophy

(1) Characteristics and Purpose of Chinese Buddhist Practice Theory

(2) Characteristics and Purpose of Neo-Confucianism’s Theory of Self-cultivation

Ⅳ.

Reviewing the Characteristics of East Asian Meditation

1.

Accepting reality and embracing change

1) Supernatural powers and overcoming death

2) Acceptance of change and idealism

2.

Theory of Dance Practice and Practice Methods of Zen and Zen Buddhism

1) Theory of Original Perfection and Uselessness of Practice

2) The structure of the entire completion and the world of the world

3.

Idealism and human existence

1) Idealism and aesthetic judgment

2) Philosophy of change and existential solutions

V.

Bringing the curtain down on the grand finale

supplement.

Unfinished problems and romantic life

main

References

Detailed image

Into the book

The Indian cultural sphere and East Asia are the two great mountain ranges that have led the spiritual culture of mankind.

However, unlike the global spread of Indian Buddhism and yoga, East Asian traditions are not neatly organized.

This is because there is a complex structure here that is difficult to organize, with Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism all mixed together.

However, East Asian spiritual culture absorbed Indian Buddhism and completed a realistic yet unique spiritual culture.

This book is a historical and practical discourse on this distinctive spiritual culture of East Asia.

--- p.6

If reality is affirmed, 'human emotions must also be affirmed', which means 'changes in reality are also affirmed'.

In this way, a 'situation of total positivity toward reality' unfolds.

The present, flowing flow of great positivity, where no problems exist, is the core characteristic of East Asian meditation.

--- p.19

If we distinguish between the phenomenal (in) and the ideal (in) and pursue the ideal among them, the phenomena we belong to will always be defined as a negative (suffering) that must be overcome.

In Indian philosophy, defining this world as 'all suffering' or 'the sea of suffering', and efforts to eliminate attachment to this world through asceticism or dhu?ta practices, all correspond to this perspective.

--- p.23

In monism, phenomena and ideals are not separate, but are merely different directions of identity, like two sides of a single coin.

This serves as the background for the emphasis on spiritualism in East Asia, which is related to the change and awakening of the subject of perception.

--- p.28

The collapse of the Heaven of Personality and the rise of the Heaven of Righteousness are due to the fact that the intervention of the Heaven of Personality is unclear in the fiercely competitive structure of the Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period, and unethical situations in which justice is defeated by strategy are common.

This leads to a departure from the belief in the personality of heaven and an expansion of human reason.

--- p.56

The 'structure in which religion is subordinated to reality (politics)' based on East Asian monism weakens the independence of religion and prevents the establishment of a view of the afterlife or the world after death.

In other words, it shows the characteristic of taking on a strong present-day structure.

Moreover, the deepening dependence on the present world inevitably fosters a strong sense of legitimacy for blood ties.

In other words, the structure becomes more solid as the emphasis on monism and lineage is interconnected.

--- p.64

The core of the East Asian ecumenical structure is not religion but worldly politics.

Here, the absence of an afterlife view according to monism also becomes an aspect that gives weight to the present world.

For this reason, East Asia is pro-political and anti-religious, that is, it is strong in politics but weak in religion, and it shows a strong realistic side.

--- p.68

Confucianism understands human life and death from the perspective of the accumulation and extinction of energy.

In the same vein, ghosts, or souls, also have their own unique properties and cannot persist independently. They are merely objects that have limitations and disperse.

In other words, there is a difference in the density of the energy (clear, turbid, thick, thin), but ghosts are not free from the energy.

--- p.76

Buddhism advocates meditative enlightenment through practice, and in fact, in the early period of Chinese Buddhism, An Shigao's Hinayana Zen view and Lokas?ema's Mahayana view were transmitted.

However, due to differences in climate and environment, these Mahayana and Hinayana practices did not have a great influence on China.

In addition, the cynical aspects of Theravada Buddhism, such as the view of impermanence or the view of impurity (or the view of white bones), were based on the dualism of Indian culture, and therefore did not fit with the Chinese way of thinking of monism.

--- p.133

The characteristic of Cheontae thought is the unity in which all things are in a relationship of mutual inclusion.

This is an unavoidable result in an understanding that assumes perfection based on monism.

This fusion of Cheontae was further developed by the Hwaeom sect, which began at Mount Zhongnan in the early Tang Dynasty, the next dynasty.

--- p.151

The Avatamsaka school of thought is broadly divided into the ‘theory of origination of nature’ and the ‘theory of dependent origination.’

The Holy Spirit is based on the “Chapter on the Arising of Tathagata Nature” and contains the content that the arising of Buddha nature, that is, “the manifestation of perfection and self-realization,” is merely a change in this world.

This is an ontological viewpoint that is in line with monistic Chinese philosophy.

The slogan of Mahayana Buddhism, "Bodhisattva," which means "everyone in the future will eventually attain Buddhahood," ultimately cannot help but manifest "present perfection" in the present.

Because becoming a perfect Buddha in the future means being perfect in the present.

--- p.153

The affirmation of reality in Chinese philosophy is expressed in the Hongzhou sect of Mazu Daoyi (709-788), a disciple of Nanyue Huaiyang (677-744).

It is the everyday life that is called ‘the everyday mind is the way.’

This is expanded to include Yunmun Mun-eon (864-949)'s 'Every day is a good day', and Imje Ui-hyeon (?-867)'s 'Mu-wi-jin-in (無位眞人)', a complete individual and existential activist who transcends discrimination.

--- p.186

If we look at the Zen of the Tang Dynasty, where the Southern School of Zen was actively developing, Zen rejects any movement that attempts to define the mind as thoughts.

In other words, it is confirmed that the change itself is immediately affirmed, rather than the dry wisdom understood with the head or thoughts.

These are the topics of conversation that are summarized in the process of legal exchange between the ancestors.

In other words, the Zen of the Tang Dynasty is not a rigid method of grasping the topic like the Ganhua Zen of the Song Dynasty's Dayeui Zonggao, but a cyclical paradox that awakens a perspective that penetrates the living actionism.

However, unlike the global spread of Indian Buddhism and yoga, East Asian traditions are not neatly organized.

This is because there is a complex structure here that is difficult to organize, with Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism all mixed together.

However, East Asian spiritual culture absorbed Indian Buddhism and completed a realistic yet unique spiritual culture.

This book is a historical and practical discourse on this distinctive spiritual culture of East Asia.

--- p.6

If reality is affirmed, 'human emotions must also be affirmed', which means 'changes in reality are also affirmed'.

In this way, a 'situation of total positivity toward reality' unfolds.

The present, flowing flow of great positivity, where no problems exist, is the core characteristic of East Asian meditation.

--- p.19

If we distinguish between the phenomenal (in) and the ideal (in) and pursue the ideal among them, the phenomena we belong to will always be defined as a negative (suffering) that must be overcome.

In Indian philosophy, defining this world as 'all suffering' or 'the sea of suffering', and efforts to eliminate attachment to this world through asceticism or dhu?ta practices, all correspond to this perspective.

--- p.23

In monism, phenomena and ideals are not separate, but are merely different directions of identity, like two sides of a single coin.

This serves as the background for the emphasis on spiritualism in East Asia, which is related to the change and awakening of the subject of perception.

--- p.28

The collapse of the Heaven of Personality and the rise of the Heaven of Righteousness are due to the fact that the intervention of the Heaven of Personality is unclear in the fiercely competitive structure of the Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period, and unethical situations in which justice is defeated by strategy are common.

This leads to a departure from the belief in the personality of heaven and an expansion of human reason.

--- p.56

The 'structure in which religion is subordinated to reality (politics)' based on East Asian monism weakens the independence of religion and prevents the establishment of a view of the afterlife or the world after death.

In other words, it shows the characteristic of taking on a strong present-day structure.

Moreover, the deepening dependence on the present world inevitably fosters a strong sense of legitimacy for blood ties.

In other words, the structure becomes more solid as the emphasis on monism and lineage is interconnected.

--- p.64

The core of the East Asian ecumenical structure is not religion but worldly politics.

Here, the absence of an afterlife view according to monism also becomes an aspect that gives weight to the present world.

For this reason, East Asia is pro-political and anti-religious, that is, it is strong in politics but weak in religion, and it shows a strong realistic side.

--- p.68

Confucianism understands human life and death from the perspective of the accumulation and extinction of energy.

In the same vein, ghosts, or souls, also have their own unique properties and cannot persist independently. They are merely objects that have limitations and disperse.

In other words, there is a difference in the density of the energy (clear, turbid, thick, thin), but ghosts are not free from the energy.

--- p.76

Buddhism advocates meditative enlightenment through practice, and in fact, in the early period of Chinese Buddhism, An Shigao's Hinayana Zen view and Lokas?ema's Mahayana view were transmitted.

However, due to differences in climate and environment, these Mahayana and Hinayana practices did not have a great influence on China.

In addition, the cynical aspects of Theravada Buddhism, such as the view of impermanence or the view of impurity (or the view of white bones), were based on the dualism of Indian culture, and therefore did not fit with the Chinese way of thinking of monism.

--- p.133

The characteristic of Cheontae thought is the unity in which all things are in a relationship of mutual inclusion.

This is an unavoidable result in an understanding that assumes perfection based on monism.

This fusion of Cheontae was further developed by the Hwaeom sect, which began at Mount Zhongnan in the early Tang Dynasty, the next dynasty.

--- p.151

The Avatamsaka school of thought is broadly divided into the ‘theory of origination of nature’ and the ‘theory of dependent origination.’

The Holy Spirit is based on the “Chapter on the Arising of Tathagata Nature” and contains the content that the arising of Buddha nature, that is, “the manifestation of perfection and self-realization,” is merely a change in this world.

This is an ontological viewpoint that is in line with monistic Chinese philosophy.

The slogan of Mahayana Buddhism, "Bodhisattva," which means "everyone in the future will eventually attain Buddhahood," ultimately cannot help but manifest "present perfection" in the present.

Because becoming a perfect Buddha in the future means being perfect in the present.

--- p.153

The affirmation of reality in Chinese philosophy is expressed in the Hongzhou sect of Mazu Daoyi (709-788), a disciple of Nanyue Huaiyang (677-744).

It is the everyday life that is called ‘the everyday mind is the way.’

This is expanded to include Yunmun Mun-eon (864-949)'s 'Every day is a good day', and Imje Ui-hyeon (?-867)'s 'Mu-wi-jin-in (無位眞人)', a complete individual and existential activist who transcends discrimination.

--- p.186

If we look at the Zen of the Tang Dynasty, where the Southern School of Zen was actively developing, Zen rejects any movement that attempts to define the mind as thoughts.

In other words, it is confirmed that the change itself is immediately affirmed, rather than the dry wisdom understood with the head or thoughts.

These are the topics of conversation that are summarized in the process of legal exchange between the ancestors.

In other words, the Zen of the Tang Dynasty is not a rigid method of grasping the topic like the Ganhua Zen of the Song Dynasty's Dayeui Zonggao, but a cyclical paradox that awakens a perspective that penetrates the living actionism.

--- p.187

Publisher's Review

The philosophy of positivity, wisdom beyond negativity

“This is the spiritual culture of East Asia!”

The Techniques of Changing Mindsets Created by East Asian Religion and Philosophy

The ultimate practice born in history: the origin and perfection of Zen.

Buddhist scholar and all-rounder Monk Ja-Hyeon recently published a new book titled “How to Achieve Enlightenment in One Shot: A Revolution in the Mind” based on his eighth doctoral thesis.

This book comprehensively examines the roots of East Asian spiritual culture and practice, as well as its modern significance.

With the abundance brought about by material civilization, along with the resulting emptiness, competition, and stress, a growing yearning for spiritual values, this book goes beyond simply introducing meditation techniques. Rather, it seeks to respond to the spiritual crisis facing modern society through the core thinking and practice (training) traditions of East Asian spiritual culture.

Standing on the path to a revolution of the mind

This book is by no means a light read.

For today's readers who experience both the limitations of material civilization and spiritual thirst, it is not simply a flow of the history of ideas, but rather a light illuminating the path to a revolution of the mind.

Rather than escaping or suppressing the imperfect reality, it is about reviving the ‘already complete me’ within it and recovering one’s own subjectivity.

This is the message that East Asian spiritual culture conveys to us today.

This book asks us:

“Can you find happiness in this moment in your life?”

This question is an invitation to a revolution that will enable a transformation of the mind in the daily lives of modern people.

The Power of a Shift in Perspective: Transforming Your Life

Humanity has constantly pursued happiness, but it still suffers from a deficiency that cannot be satisfied by the material achievements of modern society alone.

To fill this gap, yoga and mindfulness meditation have become popular not only in Western society but also around the world. However, these trends have often shown negative tendencies, such as being commercialized or privatized, focusing on the goals of 'stress relief' or 'self-development.'

These limitations dilute the essential purpose of meditation and prevent us from reflecting more deeply on human existence.

East Asian traditions, based on the ideological foundations of ancient China, adopted Indian Buddhism while also undergoing independent transformations.

So, we emphasize awareness and innovation here and now.

The author summarizes the characteristics of East Asian spiritual culture into six points.

1.

Reality positivity - accepting the imperfect reality as it is and finding happiness in it, rather than escaping or suppressing it.

2.

Sublimation of desire - Do not suppress human desires and emotions, but use them as a driving force for reflection and maturity.

3.

Awareness Awakening - Emphasizes transformational enlightenment through the moment of awakening (Don-o) rather than gradual practice.

4.

Freedom without Obstruction - Emphasizes that one can freely realize enlightenment in everyday life, without having to become a monk or undergo extreme training.

5.

No conflict with others (harmony) - Instead of forcing 'what is right', focus only on the issue of current happiness and do not create unnecessary conflict with others.

6.

Aesthetic Life - It values an attitude of aesthetically affirming human life in this world, not the next, and in the here and now, not in the transcendent.

In particular, ‘reality affirmation’, ‘sublimation of desire’, ‘raising awareness’, and ‘unhindered freedom’ are the key points emphasized in this book.

This is the power of a shift in perspective that transcends the limitations of our current society, which seeks temporary stability or simple psychological comfort while ignoring fundamental solutions by denying reality.

The author says that this power can change our entire lives.

In fact, until now, the task of comprehensively covering East Asian spiritual culture has not been easy.

Because Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism developed in a complex and intertwined manner, East Asian traditions have always remained in a state of disarray.

It was difficult to properly illuminate this issue both academically and popularly.

However, this book holds great significance in that it immediately begins that insufficient work and synthesizes the unique flow of East Asian spiritual culture into a single context.

East Asia, another spiritual mountain range

- Zen, the pinnacle of East Asian spiritual culture

This book begins with a discussion of the monistic worldview (way of thinking) of East Asia, represented by ancient China.

A monistic worldview does not establish a dichotomy between ‘this world and the other world.’

Thus, reality is viewed as a field of positivity rather than an object of escape, which is in contrast to the dualistic worldview that denies reality and pursues ideals.

East Asian monism views reality as a field of positivity, not suppressing even desires and emotions, but rather using them as a driving force for maturity and renewal.

Therefore, daily life itself becomes a place of practice.

In particular, Namjong Seon (南宗禪) further clarified the philosophy of affirming reality by affirming change and action itself as perfection through the bold proposition that “action is nature.”

Based on the monistic perspective of East Asia, the author traces the ideological fusion of Confucianism and Taoism represented by Confucius and Laozi, Buddhism introduced and formed during the Wei and Jin Southern and Northern Dynasties, and the sudden enlightenment of Huineng of the Tang Dynasty and the daily practice theory of Zonggao of Dayue of the Song Dynasty, along with the voices of specific figures and eras.

By weaving the genealogy of East Asian spiritual culture into a single flow, readers will naturally understand how East Asian spiritual culture was formed and developed, and why it is important at this point in time.

Furthermore, this exploration ultimately leads to a single practice tradition: the Zen Buddhist practice tradition.

The core of Zen practice is that practice is not a process of filling a deficiency, but a momentary revolution that reawakens one's already perfect nature.

Soon, Zen Buddhism says that practice is not separated from life, and that by changing one's perspective amidst the conflicts and desires of everyday life, one can immediately achieve freedom.

For modern people, burdened by the weight and anxiety of life, the traditions presented by Zen Buddhism come across as a revolutionary practice that touches upon life.

East Asian spiritual culture can most directly respond to the spiritual needs of modern people through “affirmation of reality, sublimation of desire, refreshing of perspective, and awareness of freedom.”

“This is the spiritual culture of East Asia!”

The Techniques of Changing Mindsets Created by East Asian Religion and Philosophy

The ultimate practice born in history: the origin and perfection of Zen.

Buddhist scholar and all-rounder Monk Ja-Hyeon recently published a new book titled “How to Achieve Enlightenment in One Shot: A Revolution in the Mind” based on his eighth doctoral thesis.

This book comprehensively examines the roots of East Asian spiritual culture and practice, as well as its modern significance.

With the abundance brought about by material civilization, along with the resulting emptiness, competition, and stress, a growing yearning for spiritual values, this book goes beyond simply introducing meditation techniques. Rather, it seeks to respond to the spiritual crisis facing modern society through the core thinking and practice (training) traditions of East Asian spiritual culture.

Standing on the path to a revolution of the mind

This book is by no means a light read.

For today's readers who experience both the limitations of material civilization and spiritual thirst, it is not simply a flow of the history of ideas, but rather a light illuminating the path to a revolution of the mind.

Rather than escaping or suppressing the imperfect reality, it is about reviving the ‘already complete me’ within it and recovering one’s own subjectivity.

This is the message that East Asian spiritual culture conveys to us today.

This book asks us:

“Can you find happiness in this moment in your life?”

This question is an invitation to a revolution that will enable a transformation of the mind in the daily lives of modern people.

The Power of a Shift in Perspective: Transforming Your Life

Humanity has constantly pursued happiness, but it still suffers from a deficiency that cannot be satisfied by the material achievements of modern society alone.

To fill this gap, yoga and mindfulness meditation have become popular not only in Western society but also around the world. However, these trends have often shown negative tendencies, such as being commercialized or privatized, focusing on the goals of 'stress relief' or 'self-development.'

These limitations dilute the essential purpose of meditation and prevent us from reflecting more deeply on human existence.

East Asian traditions, based on the ideological foundations of ancient China, adopted Indian Buddhism while also undergoing independent transformations.

So, we emphasize awareness and innovation here and now.

The author summarizes the characteristics of East Asian spiritual culture into six points.

1.

Reality positivity - accepting the imperfect reality as it is and finding happiness in it, rather than escaping or suppressing it.

2.

Sublimation of desire - Do not suppress human desires and emotions, but use them as a driving force for reflection and maturity.

3.

Awareness Awakening - Emphasizes transformational enlightenment through the moment of awakening (Don-o) rather than gradual practice.

4.

Freedom without Obstruction - Emphasizes that one can freely realize enlightenment in everyday life, without having to become a monk or undergo extreme training.

5.

No conflict with others (harmony) - Instead of forcing 'what is right', focus only on the issue of current happiness and do not create unnecessary conflict with others.

6.

Aesthetic Life - It values an attitude of aesthetically affirming human life in this world, not the next, and in the here and now, not in the transcendent.

In particular, ‘reality affirmation’, ‘sublimation of desire’, ‘raising awareness’, and ‘unhindered freedom’ are the key points emphasized in this book.

This is the power of a shift in perspective that transcends the limitations of our current society, which seeks temporary stability or simple psychological comfort while ignoring fundamental solutions by denying reality.

The author says that this power can change our entire lives.

In fact, until now, the task of comprehensively covering East Asian spiritual culture has not been easy.

Because Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism developed in a complex and intertwined manner, East Asian traditions have always remained in a state of disarray.

It was difficult to properly illuminate this issue both academically and popularly.

However, this book holds great significance in that it immediately begins that insufficient work and synthesizes the unique flow of East Asian spiritual culture into a single context.

East Asia, another spiritual mountain range

- Zen, the pinnacle of East Asian spiritual culture

This book begins with a discussion of the monistic worldview (way of thinking) of East Asia, represented by ancient China.

A monistic worldview does not establish a dichotomy between ‘this world and the other world.’

Thus, reality is viewed as a field of positivity rather than an object of escape, which is in contrast to the dualistic worldview that denies reality and pursues ideals.

East Asian monism views reality as a field of positivity, not suppressing even desires and emotions, but rather using them as a driving force for maturity and renewal.

Therefore, daily life itself becomes a place of practice.

In particular, Namjong Seon (南宗禪) further clarified the philosophy of affirming reality by affirming change and action itself as perfection through the bold proposition that “action is nature.”

Based on the monistic perspective of East Asia, the author traces the ideological fusion of Confucianism and Taoism represented by Confucius and Laozi, Buddhism introduced and formed during the Wei and Jin Southern and Northern Dynasties, and the sudden enlightenment of Huineng of the Tang Dynasty and the daily practice theory of Zonggao of Dayue of the Song Dynasty, along with the voices of specific figures and eras.

By weaving the genealogy of East Asian spiritual culture into a single flow, readers will naturally understand how East Asian spiritual culture was formed and developed, and why it is important at this point in time.

Furthermore, this exploration ultimately leads to a single practice tradition: the Zen Buddhist practice tradition.

The core of Zen practice is that practice is not a process of filling a deficiency, but a momentary revolution that reawakens one's already perfect nature.

Soon, Zen Buddhism says that practice is not separated from life, and that by changing one's perspective amidst the conflicts and desires of everyday life, one can immediately achieve freedom.

For modern people, burdened by the weight and anxiety of life, the traditions presented by Zen Buddhism come across as a revolutionary practice that touches upon life.

East Asian spiritual culture can most directly respond to the spiritual needs of modern people through “affirmation of reality, sublimation of desire, refreshing of perspective, and awareness of freedom.”

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: October 21, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 336 pages | 173*230*17mm

- ISBN13: 9791172612085

- ISBN10: 1172612080

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)