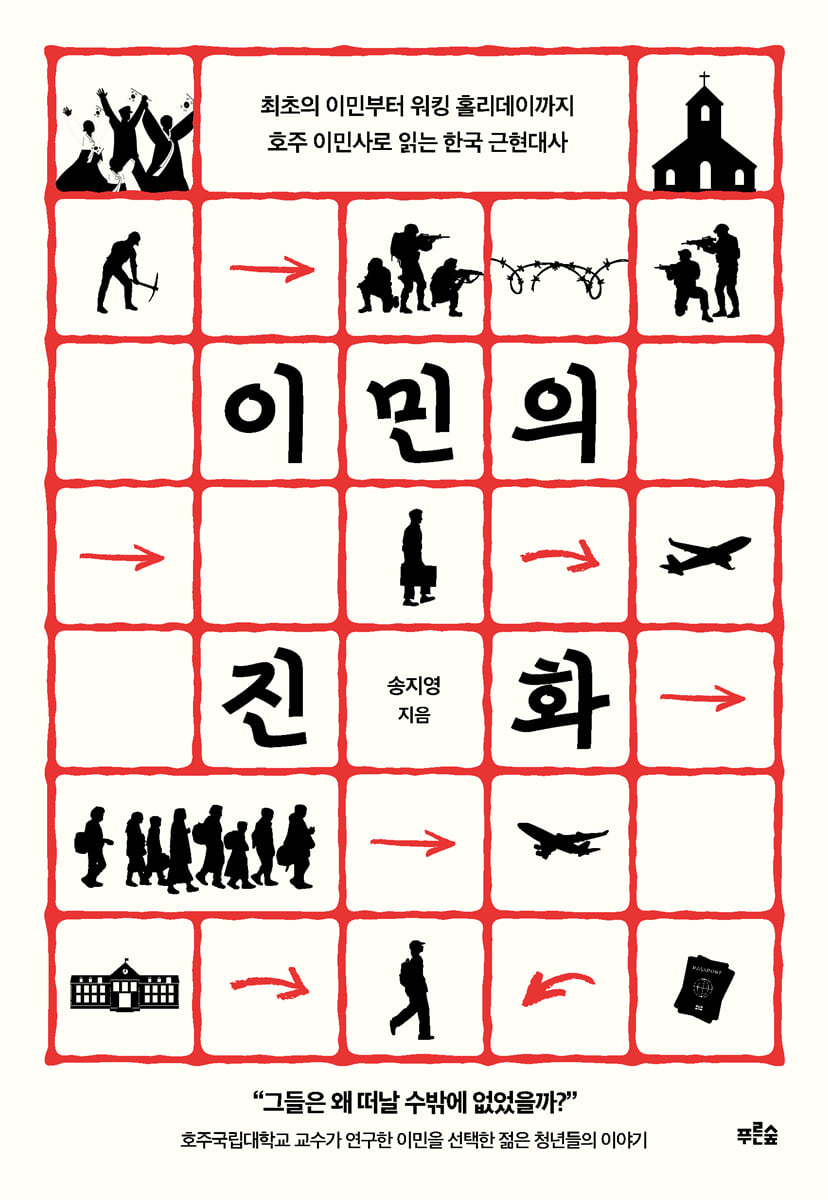

The Evolution of Immigration

|

Description

Book Introduction

“Why did young Koreans have no choice but to leave?”

From the Japanese colonial period to the present day… …

A professor at the Australian National University traces the reasons why young people left their home country over time!

Who was the first Korean to immigrate to Australia? When and for what reason? The first person to leave for Australia was a young Korean named John Corea, in the late Joseon Dynasty, during the Japanese colonial period.

After that, there was Kim Ho-yeol, the first Korean student to study at the University of Melbourne with the help of the Australian Presbyterian Church.

In a time when even finding a migration route was difficult, why did they consider leaving their homeland? What did they hope to gain by going to a foreign land where they could not speak a word or understand a single movement?

The author of this book, Professor Song Ji-young of the Australian National University, who served as the Director of Immigration Policy at the Australian Lowy Institute and is currently researching Koreans living in Australia, began by identifying the first Korean immigrant, John Corea, and interviewed first-generation immigrants who have settled in Australia, as well as young people currently on working holidays, to find the answer to this question.

This book, which compiles extensive field research over a long period of time, is organized into six chapters according to the flow of the times.

From the late Joseon Dynasty in the late 19th century to the present day, spanning over a period of nearly 100 years, the story of those who left for Australia and settled there, using various methods such as poverty, dictatorship, discrimination, and education to seek a better future for themselves or their children, is compiled in chronological order.

《The Evolution of Immigration》 begins with the research that identified the first Korean immigrant, John Korea, and tells the stories of those who left the country, either voluntarily or involuntarily, during the turmoil of the Japanese colonial period, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War.

We also examine how changes in the times, such as the liberalization of global travel and the working holiday agreement with Australia, have affected immigration.

The key to immigration research is ‘outflow factors’ and ‘inflow factors.’

Emission factors are negative factors that cause people to leave the country, either voluntarily or involuntarily.

During the height of the war, poverty and food shortages were the biggest causes of death, while now discrimination, economic limitations, and education are the main causes.

Inflow factors refer to positive factors that lead to inflow into the country.

This includes working conditions, vision, living and natural environment.

What is interesting is that the factors that drive and drive young people to change depending on the circumstances of the times.

Therefore, "The Evolution of Immigration" is not only a meaningful work that first compiles the history of immigration in Australia, but it is also an extremely interesting record that allows us to see through the twists and turns of our country's modern and contemporary history.

From the Japanese colonial period to the present day… …

A professor at the Australian National University traces the reasons why young people left their home country over time!

Who was the first Korean to immigrate to Australia? When and for what reason? The first person to leave for Australia was a young Korean named John Corea, in the late Joseon Dynasty, during the Japanese colonial period.

After that, there was Kim Ho-yeol, the first Korean student to study at the University of Melbourne with the help of the Australian Presbyterian Church.

In a time when even finding a migration route was difficult, why did they consider leaving their homeland? What did they hope to gain by going to a foreign land where they could not speak a word or understand a single movement?

The author of this book, Professor Song Ji-young of the Australian National University, who served as the Director of Immigration Policy at the Australian Lowy Institute and is currently researching Koreans living in Australia, began by identifying the first Korean immigrant, John Corea, and interviewed first-generation immigrants who have settled in Australia, as well as young people currently on working holidays, to find the answer to this question.

This book, which compiles extensive field research over a long period of time, is organized into six chapters according to the flow of the times.

From the late Joseon Dynasty in the late 19th century to the present day, spanning over a period of nearly 100 years, the story of those who left for Australia and settled there, using various methods such as poverty, dictatorship, discrimination, and education to seek a better future for themselves or their children, is compiled in chronological order.

《The Evolution of Immigration》 begins with the research that identified the first Korean immigrant, John Korea, and tells the stories of those who left the country, either voluntarily or involuntarily, during the turmoil of the Japanese colonial period, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War.

We also examine how changes in the times, such as the liberalization of global travel and the working holiday agreement with Australia, have affected immigration.

The key to immigration research is ‘outflow factors’ and ‘inflow factors.’

Emission factors are negative factors that cause people to leave the country, either voluntarily or involuntarily.

During the height of the war, poverty and food shortages were the biggest causes of death, while now discrimination, economic limitations, and education are the main causes.

Inflow factors refer to positive factors that lead to inflow into the country.

This includes working conditions, vision, living and natural environment.

What is interesting is that the factors that drive and drive young people to change depending on the circumstances of the times.

Therefore, "The Evolution of Immigration" is not only a meaningful work that first compiles the history of immigration in Australia, but it is also an extremely interesting record that allows us to see through the twists and turns of our country's modern and contemporary history.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Introduction Why did they cross the border?

Part 1

Chapter 1: Australia's First Immigrant, John Corea

Discovering the First Korean Resident in Australia│Immigrants and Citizens of Australia│A Persistent Struggle for a Living│A Mysterious Will│Countless Unrecorded John Koreas

Chapter 2: Australia's First International Student, Kim Ho-yeol

Korean Students Heading to Australia│Why Kim Ho-yeol?│A Transnational Figure Who Chaos Australia│Life on the University of Melbourne Campus│A Catalyst for Immigration

Chapter 3: To the Allied Countries to Flee the Korean War

From Australian Army mascot boy to Australian citizen│War and marriage│War orphan adoptee│The crisis of the Korean War and immigration

Part 2

Chapter 4: Chain Migration Begins in the Vietnam War

From foreign battlefields to Australia│Others from Vietnam to Australia│Youth migration fueled by a desire to survive│Secondary migration from South America to Australia│The dark side of chain migration

Chapter 5: The Crossroads Created by Early Study Abroad

Hyelin from Korea to Australia | Rose from Australia to Korea | The Relationship Between Environment and Migration | Diversifying Immigration Patterns for Korean Youth | Freely Traveling Between Two Countries, Round Trip Immigration

Chapter 6 From Working Holiday Visa to Permanent Resident

The Current Status of Korean Working Holidays in Australia│A Korean Manager at an Australian Orange Farm│A Meat Processing Plant Cleaner with an Accounting Degree│Things Working Holiday Makers Should Keep in Mind│The Evolution of Immigration

Conclusion: Immigration is a tool for evolving societies and nations.

Acknowledgements

Part 1

Chapter 1: Australia's First Immigrant, John Corea

Discovering the First Korean Resident in Australia│Immigrants and Citizens of Australia│A Persistent Struggle for a Living│A Mysterious Will│Countless Unrecorded John Koreas

Chapter 2: Australia's First International Student, Kim Ho-yeol

Korean Students Heading to Australia│Why Kim Ho-yeol?│A Transnational Figure Who Chaos Australia│Life on the University of Melbourne Campus│A Catalyst for Immigration

Chapter 3: To the Allied Countries to Flee the Korean War

From Australian Army mascot boy to Australian citizen│War and marriage│War orphan adoptee│The crisis of the Korean War and immigration

Part 2

Chapter 4: Chain Migration Begins in the Vietnam War

From foreign battlefields to Australia│Others from Vietnam to Australia│Youth migration fueled by a desire to survive│Secondary migration from South America to Australia│The dark side of chain migration

Chapter 5: The Crossroads Created by Early Study Abroad

Hyelin from Korea to Australia | Rose from Australia to Korea | The Relationship Between Environment and Migration | Diversifying Immigration Patterns for Korean Youth | Freely Traveling Between Two Countries, Round Trip Immigration

Chapter 6 From Working Holiday Visa to Permanent Resident

The Current Status of Korean Working Holidays in Australia│A Korean Manager at an Australian Orange Farm│A Meat Processing Plant Cleaner with an Accounting Degree│Things Working Holiday Makers Should Keep in Mind│The Evolution of Immigration

Conclusion: Immigration is a tool for evolving societies and nations.

Acknowledgements

Detailed image

Into the book

Since the late 19th century, the Korean Peninsula has undergone many changes.

We lost our country during the Japanese colonial period, and after experiencing two world wars, we escaped Japanese rule and achieved independence.

After being dispatched to the Korean War and the Vietnam War, and going through military dictatorship, the country achieved rapid development through freedom and globalization gained through the democratization movement.

What did the young Koreans who crossed the border hope to gain through this process?

Migration and immigration may seem similar, but they have different meanings.

Migration is a broader concept than immigration, and refers to moving from one place to another.

This includes moving from rural areas to cities for work or study, or short-term or seasonal migration from one country to another (moving to different places for specific jobs each season, for example, hiring foreign workers for short periods to help with the harvest).

Immigration means moving from one country to another for permanent settlement or long-term residence.

Accordingly, there are different factors to consider when studying migration and immigration.

While international migration studies examine the national causes and conditions that enable movement between countries, border controls, and types of visas, international migration studies primarily address local adaptation, acquisition of citizenship, racial discrimination, and identity issues, with the goal of permanent settlement.

Migration and immigration can be voluntary or involuntary, and in the case of immigration, it can be said that most cases are voluntarily planned and promoted by the will of the migrant, except for some humanitarian reasons.

Immigration to settle permanently in another country is also decided for various reasons.

Those who cannot return to their country of origin for humanitarian reasons and wish to settle permanently in a safe country may choose refugee status, while those seeking economic or family reunification may apply for permanent residency with the assistance of an employer or spouse.

In some countries, permanent residency is issued to prospective immigrants if they invest a certain amount of money.

Each country decides how many and what types of immigrants it will accept.

After selecting the necessary occupations, Australia accepts approximately 75 percent of its migrants as economic migrants, 20 percent as family migrants, and less than 10 percent as refugees and humanitarian migrants.

/ Most young immigrants are under 40 years old, earn a certain level of income through active economic activity, and pay a significant amount of tax.

Another reason why youth migration is important for the countries of origin is that most of them are likely to give birth to citizens of the country during or after their migration.

All of this adds up to the fact that young immigrants who have obtained permanent residency or citizenship are ideal citizens who have passed the rigorous standards and screening set by their countries of origin.

Finally, we must understand that youth immigration is closely linked to population policy.

Losing healthy young people with skills and a productive workforce is a national loss.

Australia has continuously developed its national strength by revising its list of occupations that are lacking locally and by securing necessary skills and labor through immigration.

The competition among developed countries to welcome young immigrants with advanced skills and labor has already begun, but South Korea is stuck in the political narrative of a homogenous nation, delaying the establishment of a strategic immigration policy at the government level.

Moreover, the number of North Korean defectors who entered South Korea through third countries since the 1990s was 34,352 as of March 2025.

However, even North Korean defectors complain of discrimination and economic difficulties.

In Korea, a country with a geopolitical location surrounded by major powers and a divided nation, if young people continue to emigrate and the workforce remains unfilled, national losses will be unavoidable.

Therefore, properly understanding the causes of youth migration is crucial for developing strategic immigration and population policies.

--- From "Preface: Why Did They Cross the Border?"

It is unknown how a 17-year-old Korean youth ended up on a ship bound for Australia in Shanghai, China in 1876.

John Corea became a citizen in 1894, 18 years after arriving in Australia.

It would be more accurate to say that he became a British citizen, as Australia was a British colony at the time.

The name he gave himself when he became naturalized was John Korea, and his real name is unknown as there are no documents such as his naturalization application form in the official Australian government records.

/ According to his naturalization certificate issued in 1894, he was born in 1859 (his death certificate states 1857), and he worked as a sheep shearer in Golgool, a small country town in western New South Wales, about a thousand kilometers from Sydney.

The year he naturalized, he was 35 years old and it is stated that he was a 'native of Corea'.

In 1894, the English name for Joseon was written in various ways, such as 'Corea, Coree, Cauli', and it was solidified as 'Korea' during the Japanese colonial period.

I couldn't be sure whether 'Corea' on the naturalization certificate meant Joseon or an Italian place name, but I assumed it was Joseon and continued my investigation.

Like John Corea, who first set foot in Australia about 150 years ago, Korean labor immigrants at the time were not upper-class people with wealth and knowledge like the yangban, but rather young people from the lower class, either middle-class or slave-born.

For them, emigration was a matter of survival.

Food security was a fundamental and key factor in youth migration during this period.

In the late Joseon Dynasty, numerous young Koreans sought to pioneer new lives by moving to China, Japan, and even further afield to Siberia and Southeast Asia.

Most of these people are lower class and are not recorded in history, which only left upper-class intellectuals, but their existence remains outside the Korean Peninsula, as in the case of John Corea.

In that respect, in addition to the Korean labor immigrants who moved to sugarcane farms in Hawaii or South America through international agreements and are recorded in history, I believe there were countless cases of individual Korean youth labor immigrants, such as John Korea, who have not been discovered.

/ John Corea, who was only 17 years old, must have had big dreams as he boarded a ship from Shanghai to Australia.

Considering that he applied for mining rights only three years after entering the country, in a place where he could not speak the language at all, one can imagine the intense life he had.

This young Korean youth spent his 20s and 30s in Australia as a short-term migrant worker, likely living with anxiety about his future.

We don't know the details of his life, but he must have done everything that made money before acquiring mining rights.

/ The reason it took him 28 years to acquire the mining rights is most likely because he is an Asian minority.

However, as his naturalization documents show, he had a strong Korean identity to the extent of using his country of origin as his English last name (Korea).

If not, our research team would not have found him now, 150 years later.

--- From "Chapter 1: Australia's First Immigrant, John Corea"

On September 6, 1921, Kim Ho-yeol arrived at 4 St. Alban S. with a Japanese passport.

Board a ship named S. St Albans and head to Australia.

At the time, the Herald reported, “Korean teacher Kim Ho-yeol came to study at the University of Melbourne at the invitation of the Presbyterian Church.

The article said, “It is expected to arrive in August.”

Kim Ho-yeol arrived in Melbourne about two weeks later, on September 19, 1921, and lived at 99 Codam Road, near Scotch College.

Kim Ho-yeol was a Victorian Presbyterian and very active in church activities, but the Japanese imperialists were extremely reluctant to accept such religious beliefs.

Because the missionaries were believed to be connected to Western anti-Japanese imperialist forces.

In fact, some Australian missionaries directly or indirectly supported the Korean independence movement to protect students.

In this political environment, it is not known to what extent Kim Ho-yeol was involved in the independence movement or whether he had any beliefs about independence.

However, if you look at the fact that he wrote his nationality and race as Joseon on his Australian entry documents, you can get a glimpse of his identity and patriotism.

In historical studies, there is a concept called 'transnational history' or 'transnational history.'

It is the study of ideas, objects, people, and customs that cross national borders, with cross-border movement and migration as the main subjects of study.

An individual's nationality is determined by complex factors such as place of birth, language, residence, citizenship, race, and national allegiance, and the transnationalism of migrants that transcends these complex factors threatens national identity itself.

/ In fact, individual movement has been taking place since the primitive times of hunting and gathering, long before the state began to control the residence and movement of its citizens.

However, race and nationality, which must be classified in the process of cross-border migration, are sometimes considered confusing and 'messiness' from an administrative and bureaucratic standpoint.

You can see this just by looking at Kim Ho-yeol's case.

In Australia, where Japan was colonizing Korea and implementing the White Australia policy, the status of a Korean student not only caused confusion regarding race and nationality among the Australian immigration authorities at the time, but was also a 'messy' existence that was not organized or categorized to the extent that even the educational institutions that taught him did not keep official records about him.

/ The study of Kim Ho-yeol is a study of transnational history, not national history.

This is a piece of transnational history, transcending the borders of the Korean Peninsula under Japanese colonial rule and Australia, which implemented the White Australia Policy, and being the first Korean student to study abroad 40 years before the establishment of official diplomatic relations between Australia and the Republic of Korea in 1961.

Through him, we can delve into the processes of colonial culture and knowledge transmission across borders, and immigration and education in the private sphere.

Restrictive immigration policies, racial discrimination, the survival strategies of individual immigrants under Japanese colonial rule, and the influence of the church as an active mediator in this process are common phenomena not only among Korean youth but also in the history of modern immigration in general.

In other words, given the limited resources and environment, individual Korean youth sought overseas migration for greater collective security, thereby maintaining and evolving the identity of the Korean community.

Kim Ho-yeol's study abroad was also about his own well-being and the future of the Korean Peninsula as an educator.

He came to Australia to escape Japanese colonial rule, but was subject to various restrictions upon entry due to the White Australia policy and was granted exemption.

He was born in what is now the Seoho region of North Korea and was a Presbyterian.

Judging from the fact that he attended Chosun Christian University, he must have belonged to the upper-middle class.

It was thanks to personal connections made through the church that he was able to come to Australia.

Kim Ho-yeol, who spoke little English, was able to study at the University of Melbourne thanks to the support of Australian missionaries in the Masan area of Gyeongnam and the Victorian Presbyterian Church.

If it weren't for the Victorian Presbyterian Church, a mediator or facilitator of educational immigration, Kim Ho-yeol's study abroad in Australia would not have happened.

/ There were shared values between Kim Ho-yeol and the church.

For Kim Ho-yeol, it was growth as a Christian leader, and for the church, it was Christian evangelism and revival through him.

His wish was to bring light to the 'dark' Joseon through Christian education.

This was in line with the values of Presbyterian overseas missions.

Because of these shared values, Kim Ho-yeol, who possessed the most suitable abilities and qualifications, was able to become the subject or object of transnational movement.

Even without a country to protect them, and even holding a passport from Japan, which had taken their country, they risked crossing borders and seas to travel and reside in Australia for the values they and their mediators pursued.

The evolution of immigration begins with transcending nationality and race.

Looking at the concept of human security discussed above and the case of Kim Ho-yeol introduced in this chapter, young people evolve in pursuit of better human security through the tools of transnational movement, that is, migration and immigration.

Kim Ho-yeol sought to pursue the identity and safety of the Korean community even under Japanese rule through studying abroad in Australia.

Although his early death prevented his realization, his ideals lived on.

If Kim Ho-yeol had safely completed his studies in Australia and returned to his home country, he would have made a significant contribution to the growth and security of the Korean community.

You will have seen him, his school, and his students grow and evolve through education, maintaining their identity and developing even within the limited environment of the Japanese colonial period.

/ During the Japanese colonial period, many young Koreans, like Kim Ho-yeol, chose to study abroad as a comprehensive calculation method of immigration to ensure collective security.

As our society develops due to the successful study abroad and return home of those who have undertaken immigration, the relationship between the two becomes increasingly complementary.

In this respect, youth immigration can be said to be a tool and medium for the evolution of society and the nation.

--- From "Chapter 2: The First Korean Student in Australia, Ho-yeol Kim"

After the war, Choi Young-gil returned to Gyeonggi Commercial High School and received a scholarship from the Australian Army, allowing him to enter Yonsei University's Department of Commerce in 1957.

He served in the Australian Army as a cartcom throughout the war, but was not recognized as a regular soldier and so returned to military service.

It was not until the armistice agreement was signed in July 1953 that KATCOM was formally recognized.

After graduating from university in 1963, Choi Young-gil was working as the Secretary General of the Korea Iron and Steel Association when he visited the Australian Embassy to find comrades from the 3rd Battalion of the Australian Army.

This became the opportunity for him to permanently immigrate to Australia on June 20, 1968, five years later, at the invitation of the Korea & South Asia Forces Association of Australia, or more precisely, the 3rd Battalion (Gapyeong Battalion) of the Australian Army that participated in the Korean War, with his wife Yang Hee-jin and their eldest daughter, Sun-eun, who was 15 months old at the time.

At that time, he was 33 years old.

Just as Kim Ho-yeol, introduced in Chapter 2, studied abroad at the University of Melbourne due to his connection with the Victorian Presbyterian Church, Choi Young-gil immigrated permanently to Sydney 18 years after arriving in Australia due to his connection with the 3rd Battalion of the Australian Army.

As such, the role of mediators and catalysts in youth immigration is crucial, and among these, invitations from influential organizations or figures in the country of residence are particularly powerful.

The Presbyterian Church of Victoria and the Korean Veterans Association of Australia played a major role in the settlement of Korean immigrants.

Not only did he invite Korean skilled immigrants and help them settle down, he also played a crucial role in fostering exchanges between the two countries by actively introducing them to Christianity, education, and transportation.

Long before Australia and the Republic of Korea established diplomatic relations in 1961, Koreans living in Australia served as a bridge between the two countries, laying a crucial foundation for the development of friendly relations between the two countries.

Although the catalysts for Kim Ho-yeol and Choi Young-gil's immigration were different—the church and the military, respectively—both groups had something in common: they were influential institutions in Australian society and economy.

Jo Young-ok married an Australian soldier and decided to follow him to Australia.

The Australian soldier returned to his home country immediately after the war and continued to keep in touch with Jo Young-ok through letters.

It was only two or three years after the war that Jo Young-ok was able to obtain a spouse visa and meet her husband.

The area where her husband lived was a small inland town three or four hours' drive from the city center, and at the time, there were no Asians living there.

/ Jo Young-ok settled in the village, relying on her husband.

She and her husband had six children, two of whom died in childhood.

Jo Young-ok used the English name Margaret, Maggie.

He said that although it must have been difficult to work the farm, do housework, and raise four children, he would never return to Korea, which was like hell.

Perhaps because of that determination, Cho Young-ok has not been active at all in the expanding Korean community in Western Australia since the 1990s.

In fact, no one in the Western Australian Korean Association knew him.

Perhaps he deliberately avoided hanging out with Koreans in Honam for fear that it would remind him of his past life in the camptown and in Korea.

War can be an opportunity for some.

There are also cases where people take advantage of the chaos to seek social advancement and act solely for personal gain.

It is a natural judgment from the perspective of basic and primitive human security, excluding political ideology and values.

From the perspective of youth immigration, it is noteworthy that the migration of war brides and Australian army mascot boys to Australia was a case of Korean youths actively taking advantage of the environment and conditions given to them to migrate to places that were politically and personally safer.

A young man from a very poor family overcomes his limitations and finds a way out to ensure his and his family's safety in the worst situation of war.

The quickest way for them to escape the political instability caused by the war and division, and the economic difficulties that followed post-war recovery, was to emigrate overseas.

At the time, immigration was not open to the lower and middle class, but a small number of people were able to forge their own path.

--- From "Chapter 3: Escape the Korean War and Go to the Allied Countries"

Citizens may consider emigrating abroad or changing their nationality if they believe that their country does not fully guarantee their safety and well-being.

Of course, not everyone who thinks about something will put it into action or have the environment to do so.

However, healthy, resourceful, and determined young people can research information on their own and seek help from those around them to make the move.

And after immigration, they build a better environment, start a family, and further expand their network by bringing in other families.

Just as birds and fish migrate to environments favorable for their reproduction, humans also evolve by constantly moving to safe places for themselves and future generations.

--- From "Chapter 4: Chain Migration Beginning with the Vietnam War"

The cases of Hyelin, who felt limited by the Korean workplace culture and settled down in Australia after developing her abilities, and Rosé, who chose to return to Korea due to racial and gender discrimination in Australia, are contrasting.

What is important here is not whether someone's choice is right or wrong, but rather how an individual's judgment about the environment influences immigration.

Since the 2000s, as the immigration routes of Korean youth have diversified, there is no case that can be said to represent the trend of Korean youth immigrating to Australia.

This is because immigration is determined by a complex interaction of all aspects, including the family environment given to an individual at birth, capabilities, immigration route, school and work, experiences through daily life, relationships with friends and spouses, presence of children, and perception of the environment.

--- From "Chapter 5: The Crossroads Created by Early Study Abroad"

Young immigrants are at the most active stage of their life cycle in terms of forward migration.

A young person who has immigrated even once is not afraid to try again.

We continuously evolve and move towards a better and safer environment for ourselves, our families, and future generations.

Evolution, as we speak of it here, refers to the natural and ecological process by which human life changes in a more advantageous and safer direction through self-organization.

One of these midnight actions is migration, emigration.

Many animals also move to favorable environments in search of food and safe shelter, and adapt and change to new environments.

The same goes for humans.

However, this book is based on complex human security requirements that go beyond basic factors such as food.

/ Adolescence is a very important time for becoming independent from one's parents, pioneering one's own life, and even finding a spouse.

Forward migration serves as an essential means of assisting their evolution.

Even if they obtain permanent residency in a place other than their birthplace, they constantly move back and forth and move forward to pursue their own development and the well-being of their families.

Through migration, they achieve a higher level of evolution than their non-migrant counterparts through their superior execution, adaptability, and quick thinking skills.

We lost our country during the Japanese colonial period, and after experiencing two world wars, we escaped Japanese rule and achieved independence.

After being dispatched to the Korean War and the Vietnam War, and going through military dictatorship, the country achieved rapid development through freedom and globalization gained through the democratization movement.

What did the young Koreans who crossed the border hope to gain through this process?

Migration and immigration may seem similar, but they have different meanings.

Migration is a broader concept than immigration, and refers to moving from one place to another.

This includes moving from rural areas to cities for work or study, or short-term or seasonal migration from one country to another (moving to different places for specific jobs each season, for example, hiring foreign workers for short periods to help with the harvest).

Immigration means moving from one country to another for permanent settlement or long-term residence.

Accordingly, there are different factors to consider when studying migration and immigration.

While international migration studies examine the national causes and conditions that enable movement between countries, border controls, and types of visas, international migration studies primarily address local adaptation, acquisition of citizenship, racial discrimination, and identity issues, with the goal of permanent settlement.

Migration and immigration can be voluntary or involuntary, and in the case of immigration, it can be said that most cases are voluntarily planned and promoted by the will of the migrant, except for some humanitarian reasons.

Immigration to settle permanently in another country is also decided for various reasons.

Those who cannot return to their country of origin for humanitarian reasons and wish to settle permanently in a safe country may choose refugee status, while those seeking economic or family reunification may apply for permanent residency with the assistance of an employer or spouse.

In some countries, permanent residency is issued to prospective immigrants if they invest a certain amount of money.

Each country decides how many and what types of immigrants it will accept.

After selecting the necessary occupations, Australia accepts approximately 75 percent of its migrants as economic migrants, 20 percent as family migrants, and less than 10 percent as refugees and humanitarian migrants.

/ Most young immigrants are under 40 years old, earn a certain level of income through active economic activity, and pay a significant amount of tax.

Another reason why youth migration is important for the countries of origin is that most of them are likely to give birth to citizens of the country during or after their migration.

All of this adds up to the fact that young immigrants who have obtained permanent residency or citizenship are ideal citizens who have passed the rigorous standards and screening set by their countries of origin.

Finally, we must understand that youth immigration is closely linked to population policy.

Losing healthy young people with skills and a productive workforce is a national loss.

Australia has continuously developed its national strength by revising its list of occupations that are lacking locally and by securing necessary skills and labor through immigration.

The competition among developed countries to welcome young immigrants with advanced skills and labor has already begun, but South Korea is stuck in the political narrative of a homogenous nation, delaying the establishment of a strategic immigration policy at the government level.

Moreover, the number of North Korean defectors who entered South Korea through third countries since the 1990s was 34,352 as of March 2025.

However, even North Korean defectors complain of discrimination and economic difficulties.

In Korea, a country with a geopolitical location surrounded by major powers and a divided nation, if young people continue to emigrate and the workforce remains unfilled, national losses will be unavoidable.

Therefore, properly understanding the causes of youth migration is crucial for developing strategic immigration and population policies.

--- From "Preface: Why Did They Cross the Border?"

It is unknown how a 17-year-old Korean youth ended up on a ship bound for Australia in Shanghai, China in 1876.

John Corea became a citizen in 1894, 18 years after arriving in Australia.

It would be more accurate to say that he became a British citizen, as Australia was a British colony at the time.

The name he gave himself when he became naturalized was John Korea, and his real name is unknown as there are no documents such as his naturalization application form in the official Australian government records.

/ According to his naturalization certificate issued in 1894, he was born in 1859 (his death certificate states 1857), and he worked as a sheep shearer in Golgool, a small country town in western New South Wales, about a thousand kilometers from Sydney.

The year he naturalized, he was 35 years old and it is stated that he was a 'native of Corea'.

In 1894, the English name for Joseon was written in various ways, such as 'Corea, Coree, Cauli', and it was solidified as 'Korea' during the Japanese colonial period.

I couldn't be sure whether 'Corea' on the naturalization certificate meant Joseon or an Italian place name, but I assumed it was Joseon and continued my investigation.

Like John Corea, who first set foot in Australia about 150 years ago, Korean labor immigrants at the time were not upper-class people with wealth and knowledge like the yangban, but rather young people from the lower class, either middle-class or slave-born.

For them, emigration was a matter of survival.

Food security was a fundamental and key factor in youth migration during this period.

In the late Joseon Dynasty, numerous young Koreans sought to pioneer new lives by moving to China, Japan, and even further afield to Siberia and Southeast Asia.

Most of these people are lower class and are not recorded in history, which only left upper-class intellectuals, but their existence remains outside the Korean Peninsula, as in the case of John Corea.

In that respect, in addition to the Korean labor immigrants who moved to sugarcane farms in Hawaii or South America through international agreements and are recorded in history, I believe there were countless cases of individual Korean youth labor immigrants, such as John Korea, who have not been discovered.

/ John Corea, who was only 17 years old, must have had big dreams as he boarded a ship from Shanghai to Australia.

Considering that he applied for mining rights only three years after entering the country, in a place where he could not speak the language at all, one can imagine the intense life he had.

This young Korean youth spent his 20s and 30s in Australia as a short-term migrant worker, likely living with anxiety about his future.

We don't know the details of his life, but he must have done everything that made money before acquiring mining rights.

/ The reason it took him 28 years to acquire the mining rights is most likely because he is an Asian minority.

However, as his naturalization documents show, he had a strong Korean identity to the extent of using his country of origin as his English last name (Korea).

If not, our research team would not have found him now, 150 years later.

--- From "Chapter 1: Australia's First Immigrant, John Corea"

On September 6, 1921, Kim Ho-yeol arrived at 4 St. Alban S. with a Japanese passport.

Board a ship named S. St Albans and head to Australia.

At the time, the Herald reported, “Korean teacher Kim Ho-yeol came to study at the University of Melbourne at the invitation of the Presbyterian Church.

The article said, “It is expected to arrive in August.”

Kim Ho-yeol arrived in Melbourne about two weeks later, on September 19, 1921, and lived at 99 Codam Road, near Scotch College.

Kim Ho-yeol was a Victorian Presbyterian and very active in church activities, but the Japanese imperialists were extremely reluctant to accept such religious beliefs.

Because the missionaries were believed to be connected to Western anti-Japanese imperialist forces.

In fact, some Australian missionaries directly or indirectly supported the Korean independence movement to protect students.

In this political environment, it is not known to what extent Kim Ho-yeol was involved in the independence movement or whether he had any beliefs about independence.

However, if you look at the fact that he wrote his nationality and race as Joseon on his Australian entry documents, you can get a glimpse of his identity and patriotism.

In historical studies, there is a concept called 'transnational history' or 'transnational history.'

It is the study of ideas, objects, people, and customs that cross national borders, with cross-border movement and migration as the main subjects of study.

An individual's nationality is determined by complex factors such as place of birth, language, residence, citizenship, race, and national allegiance, and the transnationalism of migrants that transcends these complex factors threatens national identity itself.

/ In fact, individual movement has been taking place since the primitive times of hunting and gathering, long before the state began to control the residence and movement of its citizens.

However, race and nationality, which must be classified in the process of cross-border migration, are sometimes considered confusing and 'messiness' from an administrative and bureaucratic standpoint.

You can see this just by looking at Kim Ho-yeol's case.

In Australia, where Japan was colonizing Korea and implementing the White Australia policy, the status of a Korean student not only caused confusion regarding race and nationality among the Australian immigration authorities at the time, but was also a 'messy' existence that was not organized or categorized to the extent that even the educational institutions that taught him did not keep official records about him.

/ The study of Kim Ho-yeol is a study of transnational history, not national history.

This is a piece of transnational history, transcending the borders of the Korean Peninsula under Japanese colonial rule and Australia, which implemented the White Australia Policy, and being the first Korean student to study abroad 40 years before the establishment of official diplomatic relations between Australia and the Republic of Korea in 1961.

Through him, we can delve into the processes of colonial culture and knowledge transmission across borders, and immigration and education in the private sphere.

Restrictive immigration policies, racial discrimination, the survival strategies of individual immigrants under Japanese colonial rule, and the influence of the church as an active mediator in this process are common phenomena not only among Korean youth but also in the history of modern immigration in general.

In other words, given the limited resources and environment, individual Korean youth sought overseas migration for greater collective security, thereby maintaining and evolving the identity of the Korean community.

Kim Ho-yeol's study abroad was also about his own well-being and the future of the Korean Peninsula as an educator.

He came to Australia to escape Japanese colonial rule, but was subject to various restrictions upon entry due to the White Australia policy and was granted exemption.

He was born in what is now the Seoho region of North Korea and was a Presbyterian.

Judging from the fact that he attended Chosun Christian University, he must have belonged to the upper-middle class.

It was thanks to personal connections made through the church that he was able to come to Australia.

Kim Ho-yeol, who spoke little English, was able to study at the University of Melbourne thanks to the support of Australian missionaries in the Masan area of Gyeongnam and the Victorian Presbyterian Church.

If it weren't for the Victorian Presbyterian Church, a mediator or facilitator of educational immigration, Kim Ho-yeol's study abroad in Australia would not have happened.

/ There were shared values between Kim Ho-yeol and the church.

For Kim Ho-yeol, it was growth as a Christian leader, and for the church, it was Christian evangelism and revival through him.

His wish was to bring light to the 'dark' Joseon through Christian education.

This was in line with the values of Presbyterian overseas missions.

Because of these shared values, Kim Ho-yeol, who possessed the most suitable abilities and qualifications, was able to become the subject or object of transnational movement.

Even without a country to protect them, and even holding a passport from Japan, which had taken their country, they risked crossing borders and seas to travel and reside in Australia for the values they and their mediators pursued.

The evolution of immigration begins with transcending nationality and race.

Looking at the concept of human security discussed above and the case of Kim Ho-yeol introduced in this chapter, young people evolve in pursuit of better human security through the tools of transnational movement, that is, migration and immigration.

Kim Ho-yeol sought to pursue the identity and safety of the Korean community even under Japanese rule through studying abroad in Australia.

Although his early death prevented his realization, his ideals lived on.

If Kim Ho-yeol had safely completed his studies in Australia and returned to his home country, he would have made a significant contribution to the growth and security of the Korean community.

You will have seen him, his school, and his students grow and evolve through education, maintaining their identity and developing even within the limited environment of the Japanese colonial period.

/ During the Japanese colonial period, many young Koreans, like Kim Ho-yeol, chose to study abroad as a comprehensive calculation method of immigration to ensure collective security.

As our society develops due to the successful study abroad and return home of those who have undertaken immigration, the relationship between the two becomes increasingly complementary.

In this respect, youth immigration can be said to be a tool and medium for the evolution of society and the nation.

--- From "Chapter 2: The First Korean Student in Australia, Ho-yeol Kim"

After the war, Choi Young-gil returned to Gyeonggi Commercial High School and received a scholarship from the Australian Army, allowing him to enter Yonsei University's Department of Commerce in 1957.

He served in the Australian Army as a cartcom throughout the war, but was not recognized as a regular soldier and so returned to military service.

It was not until the armistice agreement was signed in July 1953 that KATCOM was formally recognized.

After graduating from university in 1963, Choi Young-gil was working as the Secretary General of the Korea Iron and Steel Association when he visited the Australian Embassy to find comrades from the 3rd Battalion of the Australian Army.

This became the opportunity for him to permanently immigrate to Australia on June 20, 1968, five years later, at the invitation of the Korea & South Asia Forces Association of Australia, or more precisely, the 3rd Battalion (Gapyeong Battalion) of the Australian Army that participated in the Korean War, with his wife Yang Hee-jin and their eldest daughter, Sun-eun, who was 15 months old at the time.

At that time, he was 33 years old.

Just as Kim Ho-yeol, introduced in Chapter 2, studied abroad at the University of Melbourne due to his connection with the Victorian Presbyterian Church, Choi Young-gil immigrated permanently to Sydney 18 years after arriving in Australia due to his connection with the 3rd Battalion of the Australian Army.

As such, the role of mediators and catalysts in youth immigration is crucial, and among these, invitations from influential organizations or figures in the country of residence are particularly powerful.

The Presbyterian Church of Victoria and the Korean Veterans Association of Australia played a major role in the settlement of Korean immigrants.

Not only did he invite Korean skilled immigrants and help them settle down, he also played a crucial role in fostering exchanges between the two countries by actively introducing them to Christianity, education, and transportation.

Long before Australia and the Republic of Korea established diplomatic relations in 1961, Koreans living in Australia served as a bridge between the two countries, laying a crucial foundation for the development of friendly relations between the two countries.

Although the catalysts for Kim Ho-yeol and Choi Young-gil's immigration were different—the church and the military, respectively—both groups had something in common: they were influential institutions in Australian society and economy.

Jo Young-ok married an Australian soldier and decided to follow him to Australia.

The Australian soldier returned to his home country immediately after the war and continued to keep in touch with Jo Young-ok through letters.

It was only two or three years after the war that Jo Young-ok was able to obtain a spouse visa and meet her husband.

The area where her husband lived was a small inland town three or four hours' drive from the city center, and at the time, there were no Asians living there.

/ Jo Young-ok settled in the village, relying on her husband.

She and her husband had six children, two of whom died in childhood.

Jo Young-ok used the English name Margaret, Maggie.

He said that although it must have been difficult to work the farm, do housework, and raise four children, he would never return to Korea, which was like hell.

Perhaps because of that determination, Cho Young-ok has not been active at all in the expanding Korean community in Western Australia since the 1990s.

In fact, no one in the Western Australian Korean Association knew him.

Perhaps he deliberately avoided hanging out with Koreans in Honam for fear that it would remind him of his past life in the camptown and in Korea.

War can be an opportunity for some.

There are also cases where people take advantage of the chaos to seek social advancement and act solely for personal gain.

It is a natural judgment from the perspective of basic and primitive human security, excluding political ideology and values.

From the perspective of youth immigration, it is noteworthy that the migration of war brides and Australian army mascot boys to Australia was a case of Korean youths actively taking advantage of the environment and conditions given to them to migrate to places that were politically and personally safer.

A young man from a very poor family overcomes his limitations and finds a way out to ensure his and his family's safety in the worst situation of war.

The quickest way for them to escape the political instability caused by the war and division, and the economic difficulties that followed post-war recovery, was to emigrate overseas.

At the time, immigration was not open to the lower and middle class, but a small number of people were able to forge their own path.

--- From "Chapter 3: Escape the Korean War and Go to the Allied Countries"

Citizens may consider emigrating abroad or changing their nationality if they believe that their country does not fully guarantee their safety and well-being.

Of course, not everyone who thinks about something will put it into action or have the environment to do so.

However, healthy, resourceful, and determined young people can research information on their own and seek help from those around them to make the move.

And after immigration, they build a better environment, start a family, and further expand their network by bringing in other families.

Just as birds and fish migrate to environments favorable for their reproduction, humans also evolve by constantly moving to safe places for themselves and future generations.

--- From "Chapter 4: Chain Migration Beginning with the Vietnam War"

The cases of Hyelin, who felt limited by the Korean workplace culture and settled down in Australia after developing her abilities, and Rosé, who chose to return to Korea due to racial and gender discrimination in Australia, are contrasting.

What is important here is not whether someone's choice is right or wrong, but rather how an individual's judgment about the environment influences immigration.

Since the 2000s, as the immigration routes of Korean youth have diversified, there is no case that can be said to represent the trend of Korean youth immigrating to Australia.

This is because immigration is determined by a complex interaction of all aspects, including the family environment given to an individual at birth, capabilities, immigration route, school and work, experiences through daily life, relationships with friends and spouses, presence of children, and perception of the environment.

--- From "Chapter 5: The Crossroads Created by Early Study Abroad"

Young immigrants are at the most active stage of their life cycle in terms of forward migration.

A young person who has immigrated even once is not afraid to try again.

We continuously evolve and move towards a better and safer environment for ourselves, our families, and future generations.

Evolution, as we speak of it here, refers to the natural and ecological process by which human life changes in a more advantageous and safer direction through self-organization.

One of these midnight actions is migration, emigration.

Many animals also move to favorable environments in search of food and safe shelter, and adapt and change to new environments.

The same goes for humans.

However, this book is based on complex human security requirements that go beyond basic factors such as food.

/ Adolescence is a very important time for becoming independent from one's parents, pioneering one's own life, and even finding a spouse.

Forward migration serves as an essential means of assisting their evolution.

Even if they obtain permanent residency in a place other than their birthplace, they constantly move back and forth and move forward to pursue their own development and the well-being of their families.

Through migration, they achieve a higher level of evolution than their non-migrant counterparts through their superior execution, adaptability, and quick thinking skills.

--- From Chapter 6, From Warhol to Permanent Resident

Publisher's Review

The pioneers who opened the first door to immigration to Australia

John Corea, the first Korean living in Australia

Kim Ho-yeol, the first Korean student studying in Australia

The history of the Korean community in Australia began much earlier than one might think.

And at the beginning, there was 'John Korea', discovered by Professor Song Ji-young's team who was researching Koreans living in Australia at the Australian National University.

1876, the end of the Joseon Dynasty, was a particularly difficult time for the lower classes.

Constantly plagued by hunger, poverty, and the threat of death, they needed desperate means to survive.

John Corea headed to New South Wales, hoping to take advantage of the Australian gold rush.

But as a minority and only 17 years old, there was nothing he could do against the whites who had already taken over the gold mines.

Eventually he made a living by shearing sheep and working as a sailor in a small country town in Australia.

Records of John Corea have not been readily available since he acquired the mining rights in 1903.

Then, in 1920, when he was 61 years old, I found a record of him being admitted to Adelaide Hospital with tuberculosis.

He probably got sick from working as a miner for a long time.

He was treated at the hospital and stayed in very cheap housing for workers run by the Salvation Army before and after his hospitalization.

Hospital records from that time list John Corea's birthplace as 'Japan'.

His birthplace was listed as Japan, as Korea lost its sovereignty in 1910 and was under Japanese colonial rule until the end of World War II.

This fact confirmed that John Corea was Korean, not Italian.

(Page 48)

Of course, it is difficult to find any record of John Corea's naturalization in Australia and his efforts to promote the country called 'Joseon'.

However, judging from the fact that he wrote his country of origin on his naturalization certificate, which the author and his research team discovered by searching through his activities and old documents, as well as his name being 'Korea', it can be inferred that he played a sufficient role as a pioneer in introducing Joseon to Australia.

After John Korea, there was another Korean who set foot in Australia.

Kim Ho-yeol, the first international student to study at the University of Melbourne.

Kim Ho-yeol, who entered Australia with a Japanese passport during the Japanese colonial period with the support of the Presbyterian Church of Victoria, Australia, steadfastly tried to maintain his identity and establish his values amidst Australia's White Australia policy, which excluded people of color at the time.

In particular, he tried to maintain his identity as a Korean even under the reality of colonial rule, and the Presbyterian Church of Victoria, Australia, helped him in this.

In 1921, the Korean Peninsula was in its second year of the March 1st Independence Movement, which had begun in 1919 and spread nationwide.

Kim Ho-yeol, who was an intellectual and a teacher, could not have been unaware that his nationality was Japanese.

However, he proudly wrote 'Corea' and 'Corean' in the nationality and race columns on the immigration form.

(Page 62)

The author describes his research on Kim Ho-yeol as a ‘transnational historical study.’

Transnational history is the study of ideas, objects, people, and customs that cross national borders arbitrarily designated by a nation, and the very act of movement and migration across borders becomes a major subject of study.

The author says that Kim Ho-yeol's case provides an in-depth look at not only the transmission of culture across borders, but also the processes of immigration and education in the private sphere.

Furthermore, even in such a limited and restrictive situation, the choice to migrate to another country for a better future can be seen as a case of maintaining the identity of the Korean community while creating a new evolution.

John Corea and Kim Ho-yeol have different reasons for heading to Australia.

However, these figures reveal that there were deep roots connecting Korea and Australia even before the establishment of full-fledged diplomatic relations between the two countries.

Moreover, through this book, we can take a closer look at the lives of those who were called the "first" and indirectly experience the times in which they lived.

The trend brought about by full-scale globalization

If you know where the youth is headed

You can get a glimpse of the potential for social development.

After the Vietnam War in the 1970s, when the White Australia policy was officially abolished, many people moved to Australia with the hope of a new future.

Al Grasby, then Australia's immigration minister, toured Asian countries to encourage immigration, but South Korea banned entry to Australia because of Australia's diplomatic relations with North Korea.

But those who wanted a new life did not care about this and left to find a way.

Among them, there were many who were staying in Australia illegally, and soon after an amnesty for illegal immigrants was implemented, the number of Koreans immigrating to Australia gradually increased.

In particular, the Korean community in Australia grew in size through 'chain migration', where people brought their families in to form a single society after obtaining permanent residency.

Globalization was becoming an increasingly unstoppable global trend.

Accordingly, as Korea liberalized global travel in the 1990s, the number of elites studying abroad at an early age increased significantly.

Not only in Australia, but also in other Asian countries, young Koreans who went to study abroad underwent secondary migration for more diverse and personal reasons than poverty or hunger.

But not all of them settled abroad.

Hyelin and Rosé, both born in the 1980s and who experienced studying abroad at an early age, made contrasting decisions.

Hyelin settled down in Australia because she liked the work culture there, but Rosé, on the other hand, felt the limitations of being a minority woman and returned to Korea.

The author analyzed that in the two cases, it is impossible to distinguish right from wrong, and that the judgment of the environment one experiences and feels has a great influence on immigration.

Since the 2000s, many young Koreans have been heading to Australia using the 'working holiday' system established with Australia.

Among those the author met and interviewed while conducting field research, Namjun, who worked as a manager at an orange farm in Mildura, a rural town in Australia, through the Working Holiday program, acquired permanent residency, purchased real estate, and successfully settled in Australia.

On the other hand, there are cases like Minji, who started living in Australia as a high school student on her father's technical immigration visa and has been living in Australia for 10 years, but has not yet obtained permanent residency.

People in their 20s to 40s are the most economically active age group.

While investing in self-development to improve their education, career, and foreign language skills, this age group is also the most sensitive to minimum wage, annual salary, working hours, and working conditions.

Just as John Corea came to Australia 150 years ago in search of work, countless young Koreans are heading to Australia today in search of work.

Unlike John Corea, who worked as a miner and shearer of sheep, the occupations of young Koreans today have diversified, from simple farm labor to working in cafes, cleaning, and even as university professors.

(Page 168)

There is 150 years between John Corea, Namjoon, and Minji.

Meanwhile, the methods of immigration have changed and the reasons for immigration have also become more diverse.

Before globalization, survival migration was about escaping poverty and making a living, but now it has transformed into well-being migration that focuses on factors such as health, environment, and welfare, such as being able to live "like a human being," "like myself," and "where I want to live."

The youth in their 20s to 40s are at the peak of their economic and labor power.

Youth migration during this period serves as a yardstick for predicting social development.

Countries that receive an influx of young people receive a diverse workforce and technological capabilities, which contributes to their economic and social development.

Conversely, it is safe to say that a country where young people leave loses its driving force for development.

Nowadays, people do not decide to migrate or emigrate solely based on social circumstances.

The author, while chronologically organizing and researching Australian immigration, advises that if we want to create a more advanced society and understand which societies will lead the way, we need to look at the environments and cultures in which young people live.

John Corea, the first Korean living in Australia

Kim Ho-yeol, the first Korean student studying in Australia

The history of the Korean community in Australia began much earlier than one might think.

And at the beginning, there was 'John Korea', discovered by Professor Song Ji-young's team who was researching Koreans living in Australia at the Australian National University.

1876, the end of the Joseon Dynasty, was a particularly difficult time for the lower classes.

Constantly plagued by hunger, poverty, and the threat of death, they needed desperate means to survive.

John Corea headed to New South Wales, hoping to take advantage of the Australian gold rush.

But as a minority and only 17 years old, there was nothing he could do against the whites who had already taken over the gold mines.

Eventually he made a living by shearing sheep and working as a sailor in a small country town in Australia.

Records of John Corea have not been readily available since he acquired the mining rights in 1903.

Then, in 1920, when he was 61 years old, I found a record of him being admitted to Adelaide Hospital with tuberculosis.

He probably got sick from working as a miner for a long time.

He was treated at the hospital and stayed in very cheap housing for workers run by the Salvation Army before and after his hospitalization.

Hospital records from that time list John Corea's birthplace as 'Japan'.

His birthplace was listed as Japan, as Korea lost its sovereignty in 1910 and was under Japanese colonial rule until the end of World War II.

This fact confirmed that John Corea was Korean, not Italian.

(Page 48)

Of course, it is difficult to find any record of John Corea's naturalization in Australia and his efforts to promote the country called 'Joseon'.

However, judging from the fact that he wrote his country of origin on his naturalization certificate, which the author and his research team discovered by searching through his activities and old documents, as well as his name being 'Korea', it can be inferred that he played a sufficient role as a pioneer in introducing Joseon to Australia.

After John Korea, there was another Korean who set foot in Australia.

Kim Ho-yeol, the first international student to study at the University of Melbourne.

Kim Ho-yeol, who entered Australia with a Japanese passport during the Japanese colonial period with the support of the Presbyterian Church of Victoria, Australia, steadfastly tried to maintain his identity and establish his values amidst Australia's White Australia policy, which excluded people of color at the time.

In particular, he tried to maintain his identity as a Korean even under the reality of colonial rule, and the Presbyterian Church of Victoria, Australia, helped him in this.

In 1921, the Korean Peninsula was in its second year of the March 1st Independence Movement, which had begun in 1919 and spread nationwide.

Kim Ho-yeol, who was an intellectual and a teacher, could not have been unaware that his nationality was Japanese.

However, he proudly wrote 'Corea' and 'Corean' in the nationality and race columns on the immigration form.

(Page 62)

The author describes his research on Kim Ho-yeol as a ‘transnational historical study.’

Transnational history is the study of ideas, objects, people, and customs that cross national borders arbitrarily designated by a nation, and the very act of movement and migration across borders becomes a major subject of study.

The author says that Kim Ho-yeol's case provides an in-depth look at not only the transmission of culture across borders, but also the processes of immigration and education in the private sphere.

Furthermore, even in such a limited and restrictive situation, the choice to migrate to another country for a better future can be seen as a case of maintaining the identity of the Korean community while creating a new evolution.

John Corea and Kim Ho-yeol have different reasons for heading to Australia.

However, these figures reveal that there were deep roots connecting Korea and Australia even before the establishment of full-fledged diplomatic relations between the two countries.

Moreover, through this book, we can take a closer look at the lives of those who were called the "first" and indirectly experience the times in which they lived.

The trend brought about by full-scale globalization

If you know where the youth is headed

You can get a glimpse of the potential for social development.

After the Vietnam War in the 1970s, when the White Australia policy was officially abolished, many people moved to Australia with the hope of a new future.

Al Grasby, then Australia's immigration minister, toured Asian countries to encourage immigration, but South Korea banned entry to Australia because of Australia's diplomatic relations with North Korea.

But those who wanted a new life did not care about this and left to find a way.

Among them, there were many who were staying in Australia illegally, and soon after an amnesty for illegal immigrants was implemented, the number of Koreans immigrating to Australia gradually increased.

In particular, the Korean community in Australia grew in size through 'chain migration', where people brought their families in to form a single society after obtaining permanent residency.

Globalization was becoming an increasingly unstoppable global trend.

Accordingly, as Korea liberalized global travel in the 1990s, the number of elites studying abroad at an early age increased significantly.

Not only in Australia, but also in other Asian countries, young Koreans who went to study abroad underwent secondary migration for more diverse and personal reasons than poverty or hunger.

But not all of them settled abroad.

Hyelin and Rosé, both born in the 1980s and who experienced studying abroad at an early age, made contrasting decisions.

Hyelin settled down in Australia because she liked the work culture there, but Rosé, on the other hand, felt the limitations of being a minority woman and returned to Korea.

The author analyzed that in the two cases, it is impossible to distinguish right from wrong, and that the judgment of the environment one experiences and feels has a great influence on immigration.

Since the 2000s, many young Koreans have been heading to Australia using the 'working holiday' system established with Australia.

Among those the author met and interviewed while conducting field research, Namjun, who worked as a manager at an orange farm in Mildura, a rural town in Australia, through the Working Holiday program, acquired permanent residency, purchased real estate, and successfully settled in Australia.

On the other hand, there are cases like Minji, who started living in Australia as a high school student on her father's technical immigration visa and has been living in Australia for 10 years, but has not yet obtained permanent residency.

People in their 20s to 40s are the most economically active age group.

While investing in self-development to improve their education, career, and foreign language skills, this age group is also the most sensitive to minimum wage, annual salary, working hours, and working conditions.

Just as John Corea came to Australia 150 years ago in search of work, countless young Koreans are heading to Australia today in search of work.

Unlike John Corea, who worked as a miner and shearer of sheep, the occupations of young Koreans today have diversified, from simple farm labor to working in cafes, cleaning, and even as university professors.

(Page 168)

There is 150 years between John Corea, Namjoon, and Minji.

Meanwhile, the methods of immigration have changed and the reasons for immigration have also become more diverse.

Before globalization, survival migration was about escaping poverty and making a living, but now it has transformed into well-being migration that focuses on factors such as health, environment, and welfare, such as being able to live "like a human being," "like myself," and "where I want to live."

The youth in their 20s to 40s are at the peak of their economic and labor power.

Youth migration during this period serves as a yardstick for predicting social development.

Countries that receive an influx of young people receive a diverse workforce and technological capabilities, which contributes to their economic and social development.

Conversely, it is safe to say that a country where young people leave loses its driving force for development.

Nowadays, people do not decide to migrate or emigrate solely based on social circumstances.

The author, while chronologically organizing and researching Australian immigration, advises that if we want to create a more advanced society and understand which societies will lead the way, we need to look at the environments and cultures in which young people live.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: November 5, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 196 pages | 314g | 145*210*12mm

- ISBN13: 9791172540890

- ISBN10: 1172540896

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)